Abstract

Background

Specialist training provides skilled workforce for service delivery. Stroke medicine has evolved rapidly in the past years. No prior information exists on background or training of stroke doctors globally.

Aims

To describe the specialties that represent stroke doctors, their training requirements, and the scientific organisations ensuring continuous medical education.

Methods

The World Stroke Organization conducted an expert survey between June and November 2014 using e-mailed questionnaires. All Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries with >1 million population and other countries with >50 million population were included (n=49, total 5.6 billion inhabitants, 85% of global strokes). Two stroke experts from each selected country were surveyed, discrepancies resolved, and further information on identified stroke specific curricula sought.

Results

We received responses from 48 (98%) countries. Of ischaemic stroke patients, 64% were reportedly treated by neurologists, ranging from 5% in Ireland to 95% in the Netherlands. Per thousand annual strokes there were average 6 neurologists, ranging from 0.3 in Ethiopia to 33 in Israel. Of intracerebral haemorrhage patients, 29% were reportedly treated by neurosurgeons, ranging from 5% in Sweden to 79% in Japan, with 3 neurosurgeons per thousand strokes, ranging from 0.1 in Ethiopia to 24 in South Korea. Most countries had a stroke society (86%) while only 10 (21%) had a degree or subspecialty for stroke medicine.

Conclusions

Stroke doctor numbers, background specialties, and opportunities to specialise in stroke vary across the globe. Most countries have a scientific society to pursue advancement of stroke medicine but few have stroke curricula.

Keywords: Stroke, education, training, curriculum, specialist, workforce, organisation, college

INTRODUCTION

Given the overall worldwide body of knowledge in medicine increases constantly and at an accelerating rate, it is not possible to fully master the entire spectrum. Therefore, most doctors engage in specialist and subspecialty training. Further, continuous medical education, mostly provided by scientific specialist organisations, is necessary to maintain reasonable standards of practice. However, the way doctors are trained and healthcare services are delivered vary from country to country.

Over a period of a few decades, the treatment of stroke patients has transformed from passive observation on general medical wards to active, specialised care, rich in protocols and procedures. Stroke units and revascularisation therapies have been the most practice-changing advances. These and various other new techniques such as carotid endarterectomy, stroke intensive care, and neurosurgical interventions require highly skilled personnel.1, 2 As a consequence, a subspecialty of “strokologists” has emerged in clinical practice,3 but educational systems have often not formalised this development. Changes in stroke medicine will have profound effects on workforce demand in the future.4 Currently stroke patients are being cared for by various specialists in different settings, including neurologists, neurosurgeons, geriatricians, emergency doctors, rehabilitation specialists, and general physicians. No comprehensive data exist on global practices of educating stroke doctors.

The aim of this study was to answer three questions: Which specialties do doctors treating stroke patients represent? How are they being trained? Do they have scientific organisations to ensure quality in continuous medical education?

METHODS

The study was endorsed and co-ordinated by the Young Stroke Professionals Committee of the World Stroke Organization (WSO), the global scientific organisation for stroke medicine.

We performed an expert survey using short e-mailed questionnaires (Online Panel A). Two stroke experts from each selected country, at different stages of their career, and different institutes were approached and invited to participate. The respondents were primarily identified among WSO members, and if not available, through national stroke organisations, or stroke-related publications. An e-mail questionnaire accompanied by a letter of invitation was sent, followed by two reminders as needed. If no replies were received, another person from the same country was approached. The responses of the two experts from each country were compared. Any discrepancies were clarified with the experts and checked against further sources. Further descriptions of existing stroke-specific curricula were sought from the identified curriculum contacts.

We limited the scope of our study to countries which were Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members with >1 million population or non-OECD countries with a population of >50 million.

RESULTS

We received responses from all countries except Bangladesh, with a response rate of 98% of the countries selected. For Bangladesh we used publicly available data on numbers of doctors. The 49 countries included represent 78% of world population, 85% of world strokes, and >95% of global stroke research output.5

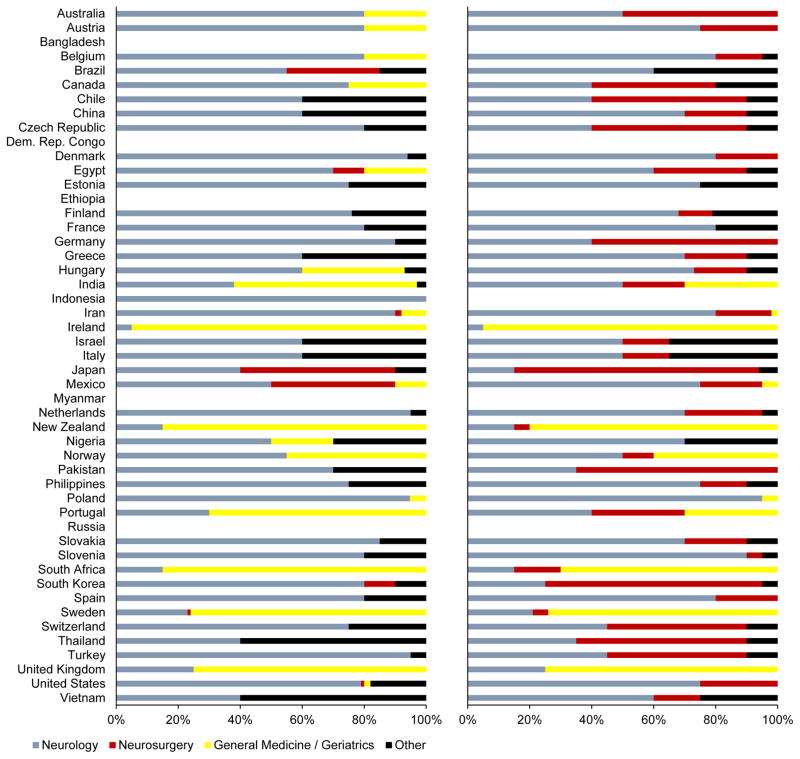

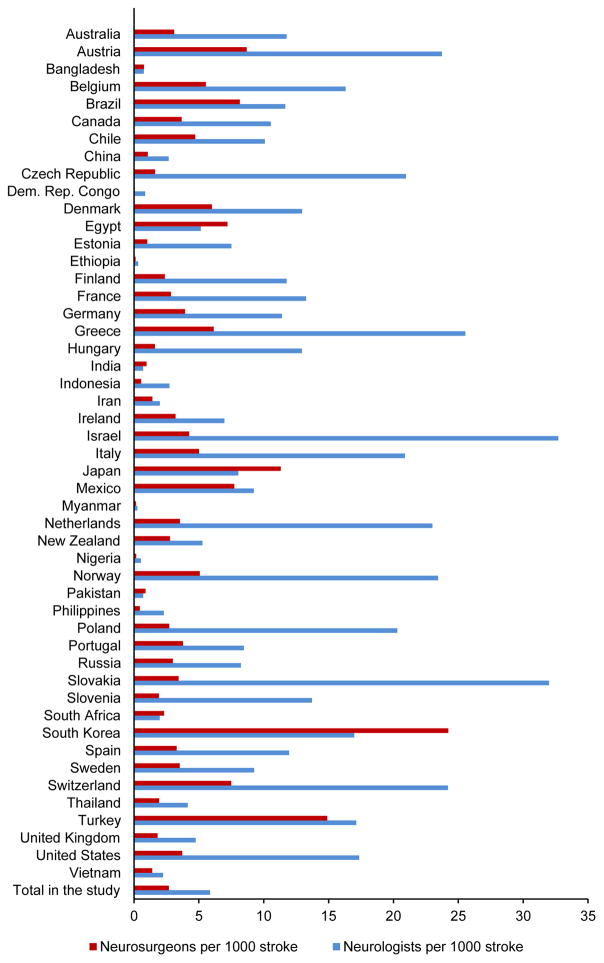

With a few exceptions,6–11 the experts did not identify published articles on the number of stroke patients treated by different specialties. Therefore the country estimates of stroke doctor specialties are mainly based on expert opinion. In most countries stroke patients were treated by neurologists. In some, mostly Commonwealth countries, general medicine was the main treating specialty. Treatment of intracerebral haemorrhage varied by country between neurology, general medicine, and neurosurgery (Figure 1). The numbers of neurologists and neurosurgeons per population differed widely by country (Table 1 and Figure 2). Also the content and duration of specialist training in neurology and neurosurgery varied across countries, being typically 5 years in duration, but ranging from 2 to 7 (Online Table I).

Figure 1.

Proportion of ischaemic stroke (left panel) and intracerebral haemorrhage (right panel) patients by treating specialty. Data are based on expert opinion with the exception of Belgium, Finland, Hungary, India, Japan, and the United States which have published data.6–11

Table 1.

Population, stroke incidence, and the numbers of neurologists and neurosurgeons

| Country | Population (millions) | Ischaemic strokes* | Haemorrhagic strokes* | Neurologists | Neurosurgeons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 22.3 | 30 | 9 | 456 | 120 |

| Austria | 8.3 | 19 | 6 | 582 | 100 |

| Bangladesh | 152.5 | 96 | 49 | 110 | 113 |

| Belgium | 10.9 | 25 | 7 | 530 | 180 |

| Brazil | 193.3 | 313 | 116 | 5 000 | 3500 |

| Canada | 34.1 | 67 | 16 | 881 | 306 |

| Chile | 17.1 | 15 | 9 | 244 | 114 |

| China | 1341.3 | 3308 | 2305 | 15 000 | 6000 |

| Czech Republic | 10.5 | 43 | 10 | 1100 | 85 |

| Dem. Rep. of the Congo | 67.5 | 37 | 20 | 49 | 4 |

| Denmark | 5.5 | 14 | 5 | 237 | 110 |

| Egypt | 86.2 | 72 | 25 | 500 | 700 |

| Estonia | 1.3 | 13 | 2 | 110 | 15 |

| Ethiopia | 86.6 | 50 | 34 | 26 | 10 |

| Finland | 5.4 | 21 | 7 | 323 | 65 |

| France | 63.0 | 119 | 40 | 2 100 | 450 |

| Germany | 81.8 | 285 | 86 | 4 238 | 1464 |

| Greece | 11.3 | 25 | 8 | 832 | 200 |

| Hungary | 10.0 | 55 | 12 | 867 | 108 |

| India | 1224.6 | 1098 | 472 | 1 100 | 1500 |

| Indonesia | 239.9 | 245 | 195 | 1 200 | 240 |

| Iran | 77.3 | 288 | 63 | 700 | 500 |

| Ireland | 4.5 | 7 | 2 | 61 | 28 |

| Israel | 7.6 | 10 | 3 | 432 | 56 |

| Italy | 60.5 | 111 | 33 | 3 000 | 720 |

| Japan | 128.1 | 458 | 180 | 5 122 | 7207 |

| Mexico | 108.4 | 89 | 35 | 1 141 | 956 |

| Myanmar | 56.2 | 49 | 38 | 22 | 13 |

| Netherlands | 16.6 | 27 | 9 | 845 | 130 |

| New Zealand | 4.4 | 6 | 2 | 40 | 21 |

| Nigeria | 173.6 | 96 | 57 | 80 | 25 |

| Norway | 4.9 | 10 | 3 | 324 | 70 |

| Pakistan | 186.0 | 114 | 54 | 120 | 150 |

| Philippines | 99.3 | 73 | 44 | 270 | 52 |

| Poland | 38.2 | 116 | 32 | 3000 | 400 |

| Portugal | 10.6 | 27 | 11 | 314 | 140 |

| Russia | 142.5 | 847 | 124 | 8000 | 2900 |

| Slovakia | 5.4 | 18 | 4 | 700 | 75 |

| Slovenia | 2.0 | 8 | 2 | 143 | 20 |

| South Africa | 56.0 | 49 | 30 | 155 | 182 |

| South Korea | 49.4 | 77 | 36 | 1 920 | 2740 |

| Spain | 46.1 | 102 | 32 | 1 607 | 442 |

| Sweden | 9.4 | 27 | 7 | 316 | 120 |

| Switzerland | 7.8 | 17 | 5 | 546 | 169 |

| Thailand | 65.9 | 114 | 67 | 750 | 350 |

| Turkey | 72.7 | 75 | 26 | 1 725 | 1500 |

| United Kingdom | 61.3 | 112 | 34 | 694 | 265 |

| United States | 309.3 | 755 | 188 | 16 366 | 3500 |

| Vietnam | 89.7 | 94 | 85 | 400 | 250 |

|

| |||||

| Total in the study | 5567 | 9726 | 4638 | 84 278 | 38 478 |

| Non-study countries | 1585 (22%) | 1844 (16%) | 687 (13%) | ||

Incidence in thousands in the year 2010 according to the Global Burden of Disease Study28

Figure 2.

Number of neurologists and neurosurgeons per 1000 annual incident stroke patients

Ten of the included countries had a specialty, subspecialty, or similar national degree in stroke medicine. Additionally, the European Stroke Organisation has a training program in collaboration with the Donau University Krems in Austria. The duration of the stroke programs ranged from 9 months to 3 years (Table 2). Further information on the programs is available via links in Online Panel B.

Table 2.

Stroke specific degrees by country

| France | Hungary | Ireland | Israel | Japan | Mexico | Switzerland | Thailand | UK | USA | ESO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke degree type | Academic degree | State Licence (previously Diploma of Hungarian Stroke Society) | Academic degree | Fellowship | Certification by Japan Stroke Society | Academic degree | Certification by Swiss Neurological Society | Academic degree | Academic degree | Certification by American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology | Master in Stroke Medicine co-hosted by the ESO and Donau University Krems |

| Initiation year | 1998 | 2014(Licen.) 2002(Dipl) |

2009 | 2011 | 2003 | 1990 | Early 1990’s | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2006 |

| Degree holders | >500 | 60 (Dipl.) | N.A. | N.A. | 3657 | ~50 | >100 | 40 | N.A. | ~1200 | ~100 |

| Specialists entry requisite | Neurology, Surgery, Radiology, Paediatrics, Cardiology, Vascular surgery, Rehab med. | Neurology, Cardiology, Internal medicine | Medical degree | Neurology, Neurosurg., Internal medicine | Neurology, Neurosurg, Radiology, Paediatrics, Internal/Emergency/Rehab med. | Neurology | N.A | N.A. | Neurology, Cardiology, Internal medicine, Geriatrics, Clinical pharmacol, Rehab med. | Neurology | |

| Duration, y | 2 | 2 | 0.75 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Brief description of stroke degree content | Theoretical: 6 modules (2 days each); Practical: Min. 1 year as resident or min. 6 months as assistant in accredited stroke unit and at least 20 duties in accredited stroke unit | N.A. | Theoretical: 7 modules (2 days each); | Acute stroke unit care, stroke clinics, neuro-sonology, stroke meetings, contact with stroke rehab, research project | 3-year experience of stroke patients care in training site |

Theoretical: Courses Research projects Participation in clinical and academic sessions Practical: Stroke clinic duty |

Clinical education in stroke medicine and ultrasound, final exams | Stroke fellowship program include acute stroke treatment, prevention and neuro-sonology | Theoretical and practical training | Theoretical and practical training |

Theoretical: Four weeks in Austria, online studies, master’s thesis Practical: Four weeks in international stroke centres of excellence |

ESO, European Stroke Organisation. See Online Panel B for websites and contact details.

All but 7 of the countries had a national stroke society. Many, but not all of these societies were member organisations of the WSO. The highest WSO member rates per population were from Australia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Scientific stroke societies and World Stroke Organization membership by country

| Country | National scientific stroke society | WSO organizational members scientific/support | WSO individual members | WSO individual members per 10 million population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | + | 1/1 | 215 | 96 |

| Austria | + | 14 | 17 | |

| Bangladesh | + | 1/- | 3 | 0.2 |

| Belgium | + | 1/- | 11 | 10 |

| Brazil | + | 2/1 | 38 | 2 |

| Canada | + | 2/1 | 65 | 19 |

| Chile | No | 6 | 4 | |

| China | + | 1/- | 806 | 6 |

| Czech Republic | + | 6 | 6 | |

| Dem. Rep. of the Congo | No | 1 | ||

| Denmark | + | 1/- | 3 | 5 |

| Egypt | + | 56 | 6 | |

| Estonia | + | 0 | ||

| Ethiopia | No | 0 | ||

| Finland | + | 1/1 | 16 | 30 |

| France | + | 1/- | 13 | 2 |

| Germany | + | 1/- | 45 | 6 |

| Greece | + | 1/- | 5 | 4 |

| Hungary | + | 2 | 2 | |

| India | + | -/2 | 50 | 0.4 |

| Indonesia | + | 1/- | 16 | 1 |

| Iran | No | 2/- | 105 | 14 |

| Ireland | + | 11 | 24 | |

| Israel | No | -/1 | 5 | 7 |

| Italy | + | 22 | 4 | |

| Japan | + | 2/- | 100 | 8 |

| Mexico | + | 7 | 1 | |

| Myanmar | No | 5 | 1 | |

| Netherlands | + | 13 | 8 | |

| New Zealand | + | -/1 | 23 | 52 |

| Nigeria | + | 1/1 | 17 | 1 |

| Norway | + | 9 | 18 | |

| Pakistan | + | 1/- | 4 | 0.2 |

| Philippines | + | 1/- | 10 | 1 |

| Poland | + | 1/- | 5 | 1 |

| Portugal | + | 1/- | 7 | 7 |

| Russia | + | 5 | 0.4 | |

| Slovakia | + | 1 | 2 | |

| Slovenia | + | 1 | 5 | |

| South Africa | + | 0/2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| South Korea | + | 1/- | 57 | 12 |

| Spain | + | 1/- | 19 | 4 |

| Sweden | No | 10 | 11 | |

| Switzerland | + | 1/1 | 19 | 24 |

| Thailand | + | 1/- | 46 | 7 |

| Turkey | + | 1/- | 9 | 1 |

| United Kingdom | + | 2/2 | 66 | 11 |

| United States | + | 2/3 | 99 | 3 |

| Vietnam | + | 7 | 1 | |

|

| ||||

| Total in the study | 32/17 | 2054 | 4 | |

| Excluded countries | 7/3 | 127 | ||

DISCUSSION

As health service delivery in the field of stroke is rapidly evolving, and in light of the increasing stroke incidence due to an aging world population, stroke specialist training faces distinct challenges. In this survey we, for the first time, summarised the specialist background, current curricula, and national scientific societies in stroke medicine. While the main speciality responsible for stroke in most countries was identified as neurology, many countries are an exception to this rule, and the main treating specialty of intracerebral haemorrhage varied widely. Stroke societies exist in almost every country but stroke curricula are less common. These existing stroke programmes can be utilized as a framework by countries and organisations that plan to develop a new, or revise an existing, stroke training curriculum.

Notably, in many countries, the main treating specialty for stroke is internal/general/geriatric medicine. Although risk factors for stroke and acute complications fall largely in the field of these specialties, the differential diagnosis and long-term complications are neurological. Therefore, neurologists well trained in general medicine may be best suited to treat stroke patients.

Specialist training in medicine and neurology is rapidly changing, with a trend towards subspecialisation.12 In the English literature, a subspecialty in stroke was first suggested in 1997,13 and then established in 2003 in the USA14 and in 2004 in the UK.15 Later, subspecialty training in neurovascular interventions16 and neurocritical care17 have been set up in the USA. Even working fulltime in a hospital, the so-called “neurohospitalist” has been suggested to be a specialised group of neurologists.18 A policy paper on what European young neurologists considered important in stroke training has been published,19 but has received little attention since. Despite harmonisation of higher education in Europe through the Bologna process, the education and healthcare systems still differ widely within the continent. Basic medical degrees are mostly not involved in this European unification, and specialist training not at all. To our knowledge, no other attempts exist for harmonising medical education internationally. The data published here provides new insights into how stroke is being taught globally and may serve to help build collaborations between different systems and thus converge education in the future.

A recent literature review of medical education in the field of neurology failed to identify any articles comparing specialist training programmes in neurology or stroke.20 There is very little data on stroke education overall. In 1992, primary care physicians’ and second year medical students’ knowledge on stroke was studied in Minnesota, USA, finding disturbing knowledge gaps in both groups.21 In 1995, a report on undergraduate and postgraduate training in cerebrovascular disease, based on a survey of 40 centres in USA and Canada, concluded that stroke was hardly being taught at all during the course of basic medical training or specialist training in internal medicine.22 When stroke components have been introduced to basic medical training, retained learning and student satisfaction were demonstrated in a study at the University of Massachusetts.23 Neurology specialist curricula and training practices have been evaluated on national level in Finland, but only published in Finnish.24 It is quite possible that there are many other national and nationally published studies on specialist training which we were not able to identify. As specialist medical training in general serves national demand, details are often not available in English or published in the international literature. We were positively surprised to learn of the 11 existing curricula described in Table 2 and Online Panel B. For most countries, the language barrier prevents gaining detailed data on their national specialist training programmes based on publicly available materials alone. Such data is crucial for planning of new curricula, revision of existing curricula, any attempts at harmonisation, and to inform policies around international mobility of clinicians.

We observed marked differences in the numbers of neurologists and neurosurgeons by country (Figure 2). All the ten countries with >20 neurologists/1000 stroke cases per year were in Europe, while some European countries such as Sweden, UK, and Ireland had substantially fewer – these were the same countries where stroke was less often treated by neurologists. Similarly, there were more neurosurgeons than neurologists in Japan and South Korea, the countries where a significant number of stroke patients were treated by neurosurgeons. Our data provides no answer as to whether the observed differences in treatment practices are a consequence of the available workforce or vice versa. Overall resource of neurologists and neurosurgeon were low in low and middle income countries (Figure 2). A possible effective strategy for these countries may be the engagement of their nationals in diaspora in high income nations who have acquired high levels of skills in stroke medicine to use their expertise and experiences to help build effective systems in their home nations.25

Our survey was limited to only two responses per country. We sought national experts to help identify existing literature on specialties treating stroke patients. Very little published data was identified, and therefore most of the estimates are based on expert opinion only. These opinions represent only limited geographic locations and select, more often academic, institutions. It is also possible the national experts missed some existing published data. Therefore, our estimates may not be accurate and probably overestimate specialist involvement in stroke care overall. This underlines the need to collect and publish more high quality data on medical specialists treating stroke patients which can be used for planning the basic and continuous education of these doctors. Also, the interesting finding of how care of stroke patients is divided equally between neurologists and neurosurgeons in many countries suggests a more collaborative approach might be warranted in medical education, and at scientific society level between these specialties. Finally, our survey was performed in 2014 prior to the publication of the positive endovascular clot retrieval trials. For this reason we did not collect data on training of interventional neuroradiology. This is an important topic and should be included in future updates of our survey.

To conclude, stroke medicine is practised by doctors of various training background in different countries of which few have specific training programs for stroke. Still, most do have a scientific society, the first requirement to start evolving such curricula. In many countries stroke patients are not treated by doctors specialised in stroke medicine, but rather by generalists. Treatment of stroke patients by specialists has been associated with better conformance with guidelines, shorter hospital stays, and improved patient outcomes.6, 26, 27 Thus, an efficient training system providing stroke specialists would likely have direct benefit on patient outcomes. It would serve stroke patients well to have more stroke specialists taking care of them. No comprehensive data have previously been compiled on the variance of different national practices of educating and scientifically organising stroke specialists. We hope our data serves to inspire developments in countries where such systems are yet to be implemented, and to promote interaction between existing national organisations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the numerous national experts who offered their time and expertise allowing us to collate this report.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Dr. Henninger is supported by K08NS091499 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr Meretoja conceived and co-ordinated the project and drafted the manuscript. All authors collected data; interpreted the data; and edited the manuscript for important intellectual contribution.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors are members of the WSO Young Stroke Professionals Committee and/or the Board. WSO is the global body for advancement of stroke medicine. Prof Brainin is the head of the Master in Stroke Medicine training programme at the Donau University Krems.

References

- 1.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, Jr, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner T, Al-Shahi Salman R, Beer R, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:840–855. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnan GA, Davis SM. Neurologist, internist, or strokologist? Stroke. 2003;34:2765. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000098002.30955.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zipfel GJ, Derdeyn CP, Dacey RG., Jr Current status of manpower needs for management of cerebrovascular disease. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:S261–270. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000237509.92730.D3. discussion S263–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asplund K, Eriksson M, Persson O. Country comparisons of human stroke research since 2001: a bibliometric study. Stroke. 2012;43:830–837. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.637249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meretoja A, Kaste M, Roine RO, et al. Trends in treatment and outcome of stroke patients in Finland from 1999 to 2007. PERFECT Stroke, a nationwide register study. Ann Med. 2011;43:S22–S30. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.586361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belgian Stroke C, Thijs V, Peeters A, et al. Organisation of inhospital acute stroke care and minimum criteria for stroke care units. Recommendations of the Belgian Stroke Council. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toyoda K. Contribution of neurologists to emergent stroke medicine in Japan. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2013;53:1370–1372. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.53.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandian JD, Kalra G, Jaison A, et al. Knowledge of stroke among stroke patients and their relatives in Northwest India. Neurol India. 2006;54:152–156. discussion 156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramirez L, Krug A, Nhoung H, et al. Vascular Neurologists as Directors of Stroke Centers in the United States. Stroke. 2015;46:2654–2656. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bereczki D, Ajtay A. Neurology 2009: a survey of Hungarian neurology capacities, their utilization and of neurologists, based on 2009 institutional reports in Hungary. Ideggyogy Sz. 2011;64:173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aminoff MJ. Training in neurology. Neurology. 2008;70:1912–1915. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312287.53064.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bath P, Lees K, Dennis M, et al. Should Stroke Medicine Be a Separate Subspecialty? BMJ. 1997;315:1167–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams HP, Jr, Biller J, Juul D, Scheiber S. Certification in vascular neurology: a new subspecialty in the United States. Stroke. 2005;36:2293–2295. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185685.20612.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starke I. Stroke medicine: a new subspecialty. Hosp Med. 2004;65:369–370. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2004.65.6.13767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen M, Nguyen T. Emerging subspecialties in neurology: endovascular surgical neuroradiology. Neurology. 2008;70:e21–24. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000299086.22147.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zakaria A, Provencio JJ, Lopez GA. Emerging subspecialties in neurology: neurocritical care. Neurology. 2008;70:e68–69. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310991.31184.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Josephson SA, Engstrom JW, Wachter RM. Neurohospitalists: an emerging model for inpatient neurological care. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:135–140. doi: 10.1002/ana.21355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corea F, Gunther A, Kwan J, et al. Educational approach on stroke training in Europe. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2006;28:433–437. doi: 10.1080/10641960600549959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stern BJ, Lowenstein DH, Schuh LA. Invited article: Neurology education research. Neurology. 2008;70:876–883. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304745.93585.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen SS, Harris IB, Kofron PM, et al. A comparison of knowledge of medical students and practicing primary care physicians about cardiovascular risk assessment and intervention. Prev Med. 1992;21:436–448. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90052-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberts MJ. Undergraduate and postgraduate medical education for cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1995;26:1849–1851. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.10.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billings-Gagliardi S, Fontneau NM, Wolf MK, Barrett SV, Hademenos G, Mazor KM. Educating the next generation of physicians about stroke: incorporating stroke prevention into the medical school curriculum. Stroke. 2001;32:2854–2859. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.099651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meretoja A, Kantanen A-M. Neurologit tekivät sen taas – Auditointien tuloksena entistä parempaa erikoislääkärikoulutusta [Audit Results of Neurology Training in Finland] Finnish Med J. 2009;64:388–393. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imam I, Akinyemi R. Nigeria. Pract Neurol. 2015;16:75–77. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaste M, Palomaki H, Sarna S. Where and how should elderly stroke patients be treated? A randomized trial. Stroke. 1995;26:249–253. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith MA, Liou JI, Frytak JR, Finch MD. 30-day survival and rehospitalization for stroke patients according to physician specialty. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;22:21–26. doi: 10.1159/000092333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnamurthi RV, Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Global and regional burden of first-ever ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e259–281. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70089-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.