Abstract

Objective:

Survey studies provide evidence that experiencing intimate partner aggression (IPA) contributes to subsequent alcohol use. However, it is unknown whether the increase in alcohol use over time reflects a temporal effect of IPA. We examined verbal and physical IPA as predictors of alcohol use and heavy drinking within the next few hours. We also investigated whether both victims and perpetrators drank following IPA, and if it mattered which partner reported the aggression.

Method:

The data reported here were derived from a 56-day diary study examining the association between alcohol use and partner aggression in 118 heterosexual couples. We examined whether alcohol use in a given hour could be predicted by IPA in the previous 3 hours, taking into account victim/perpetrator status, source of the report (self, other), and gender.

Results:

Victims were twice as likely to use alcohol in a given hour when they reported having received verbal IPA in the previous 3 hours, independent of the perpetrator’s report. Similarly, perpetrators were more than twice as likely to use alcohol in a given hour when they reported having perpetrated verbal IPA in the previous 3 hours, independent of the victim’s report. Results were similar when reports of mutual IPA were considered. Verbal IPA increased the likelihood of drinking but not the likelihood of heavy drinking. Results for physical IPA were not significant.

Conclusions:

Verbal IPA is a proximal predictor of alcohol use for both victims and perpetrators. However, effects emerge only when individuals report aggression, and not when their partner provides the sole report, emphasizing the importance of the individual’s perception of IPA.

Survey studies provide evidence that experiencing intimate partner aggression (IPA) contributes to subsequent alcohol use (e.g., Keller et al., 2009; Martino et al., 2005; Testa & Leonard, 2001; Testa et al., 2003). However, it is unknown whether the increase in alcohol use over time reflects a temporal effect of IPA—that is, whether an episode of aggression leads to an episode of drinking within the next few hours. Drinking might increase following IPA as an acute method of regulating negative affect (e.g., Marlatt et al., 1975; Mohr et al., 2001) or only as a long-term method of self-medicating (e.g., Lindgren et al., 2012; Øverup et al., 2015).

The current study examined the temporal association of verbal IPA (e.g., yelling, insulting, or making threats) and physical IPA (e.g., throwing things, pushing, or hitting) with subsequent alcohol consumption, using 56 days of daily reports. We considered whether IPA was a proximal predictor of subsequent drinking and heavy drinking. We also examined whether both victims and perpetrators drank following IPA, and if it mattered which partner reported the aggression.

Stressful interpersonal events predict alcohol use

Experimental evidence links stressful interpersonal events with greater alcohol use in ad lib drinking paradigms. Participants who suppress their thoughts and feelings during and immediately following an aversive interpersonal experience, such as being evaluated by others, consume more alcohol than participants who do not (e.g., Hamilton & DeHart, 2016; Higgins & Marlatt, 1975; Marlatt et al., 1975; Thomas et al., 2011). Within a laboratory setting, however, participants are only given choices of whether and how much to drink. In daily life, people can choose from many other responses to stress.

Daily process research supports the notion that alcohol use increases in response to stressful interpersonal events. On days when participants report experiencing negative interactions with others, they are more likely to drink (DeHart et al., 2009; Mohr et al., 2001). The relationship is complex and depends on such variables as drinking contexts, individual differences in drinking motives, and personality traits such as neuroticism and self-esteem (DeHart et al., 2009; Mohr et al., 2001). To date, little research has considered the predictive utility of IPA (for exceptions, see Parks et al., 2008; Shorey et al., 2016a).

Does intimate partner aggression predict alcohol use?

Although not specific to IPA, daily process research has shown that experiencing negative relationship events (e.g., conflict) on a given day is associated with a greater likelihood of drinking later that day, but only among people with low self-esteem (DeHart et al., 2008). Similarly, experiencing more negative relationship events, decreased closeness, or greater negative partner behavior (e.g., criticism) on a given day is associated with increased likelihood of drinking and increased number of drinks later that day and the following day, particularly among women (Levitt & Cooper, 2010). Together, these studies suggest that relationship conflict, but not specifically IPA, puts people at risk for drinking in the short term.

Consistent with our predictions, Parks et al (2008) found that verbal aggression (but not physical or sexual aggression) on a given day is associated with an increased likelihood of drinking on the following day. However, they did not examine immediate (i.e., same day) consequences of aggression on alcohol use, differentiate between victimization and perpetration, or specify that the aggression occur within an intimate relationship. In the context of dating relationships, Shorey et al. (2016a) examined the effects of physical and sexual IPA on next-day alcohol and cannabis use. They obtained significant effects of IPA for cannabis but not for alcohol. However, they did not examine the effects of verbal IPA, and they focused only on the substance use of the victims. Neither Parks et al. (2008) nor Shorey et al. (2016a) found significant effects of physical IPA on subsequent alcohol use, but it is difficult to know what to make of these null results, given the small number of physical IPA events reported (16 events in Parks et al., 2008; 46 events in Shorey et al., 2016a).

Overview and hypotheses

The present study examined the temporal impact of verbal IPA on alcohol consumption within the next 3 hours. We expected increased alcohol use among those who reported having received verbal IPA, as victims might drink to alleviate distress (e.g., Øverup et al., 2015). However, we reasoned that we might also observe increased alcohol use among those who reported having perpetrated verbal IPA, as perpetrators might drink to lessen anger or dampen physiological arousal (e.g., Marlatt et al., 1975). We expected comparable results for physical aggression, but we recognized that we might not have enough power to detect an effect.

Examining the association between IPA and alcohol use is complicated by the surprisingly low agreement between relationship partners regarding the occurrence of IPA (Caetano et al., 2009; Schafer et al., 2002; Testa et al., 2012). For example, one partner may report an episode of IPA in which she both perpetrated and experienced victimization; however, her partner may report only perpetration, only victimization, or neither. Without independent corroboration, it is not possible to assess the validity of separate partner reports. Therefore, we chose to treat separate partner reports as distinct pieces of information with differential predictive ability, consistent with previous analyses of this data set (Derrick et al., 2014). We expected that we would observe increased alcohol use only among individuals who reported having experienced IPA (as victims or perpetrators) and not among individuals whose partners provided the sole report.

Method

Participants

The data reported here were derived from a daily diary study examining the association between alcohol use and IPA in heterosexual couples (Testa & Derrick, 2014). This study received human subjects’ approval from the University at Buffalo’s Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited through advertisements and targeted household mailings and were screened for eligibility for a laboratory study involving alcohol administration (Testa et al., 2014). To be eligible, both partners had to consume alcohol on a weekly basis and engage in heavy episodic drinking (HED; at least 4/5 drinks for women/men in one sitting) at least once per month. Neither partner could report medical contraindications to alcohol consumption, meet criteria for alcohol dependence, or report extremely severe partner violence (e.g., use of a weapon). Approximately 6 months after completing the laboratory study, couples were rescreened for eligibility and interest in the daily diary study. Of the 152 couples that completed the alcohol administration study, 96 participated in the daily diary. An additional 22 couples participated in the daily diary but not the alcohol administration study. The final daily diary sample consisted of 118 married and cohabiting couples between ages 21 and 45.

The men in the sample averaged 33.9 (SD = 6.8) and women 32.7 (SD = 6.9) years of age. Most participants were White (91.5% of men and 95.8% of women), had at least some college education (87% of men and 95% of women), and were employed at least part time (91.5% of men and 77.1% of women). The median household income was $60,000–$75,000 (in U.S. dollars). Most couples were married (76% vs. 24% cohabiting) and had been living together for an average of 6.3 years (SD = 5.1). The majority (63%) had children.

Procedures

Following a 45-minute training session, both partners completed independent daily reports using interactive voice response technology for 56 days. Participants called the interactive voice response system each day to respond to recorded questions using the keypad on their phone. They were instructed to complete their reports at approximately the same time each day. Each partner was compensated $1 for each report, $10 for each complete week of reports, and a $30 bonus for 8 complete weeks of reports. Participants who missed a day were permitted to submit an abbreviated report on the following day (resulting in nearly 100% of days complete). Participants completed their reports on time 87.9% (men) and 87.2% (women) of days. We report analyses based on all reports completed. Results were consistent when only on-time reports were analyzed.

Daily report measures

Daily questions assessed mood, relationship functioning, positive events, conflict events, and alcohol (see Derrick et al., 2014, and Testa & Derrick, 2014, for more details). Because we expected that most couple interactions and alcohol use would occur in the evenings, possibly after participants had completed their reports for that day, each report assessed conflict and alcohol use for the previous day.

Intimate partner aggression.

Participants were asked, “At any time yesterday, did you and your partner have a conflict, argument, or disagreement, whether major or minor?” Participants who responded positively were asked to record the hour the conflict began and its duration. In addition, they were asked whether the conflict included behaviors derived from the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2; Straus et al., 1996). Each behavior was asked about twice to assess the participant’s behavior directed toward the partner and the partner’s behavior toward the participant. A positive response to yelled, insulted, or made threats was scored as verbal IPA, and a positive response to threw/kicked/hit something or pushed/grabbed/hit was scored as physical IPA. Participants who reported a conflict also were asked whether any other conflict occurred that day, and, if so, follow-up questions were repeated. Two conflicts were reported on 2.7% and 2.2% of conflict days for men and women, respectively.

Alcohol use.

Each day, participants were asked, “Yesterday, did you drink any alcoholic beverages?” Participants who responded positively were asked the hour the drinking episode began, its duration, the number of drinks, and how intoxicated they felt. Participants who reported a drinking episode were asked whether there was another drinking episode that day, and, if so, they were asked the same follow-up questions. Two alcohol use episodes were reported on 7.9% and 6.5% of alcohol use days for men and women, respectively.

Analytic strategy

To disentangle the temporal ordering of the IPA and alcohol use variables, we considered the occurrence of alcohol use in a given hour as a function of IPA in the previous 3 hours. We began by dividing each day into 24 1-hour segments. Then, we created lagged predictor variables by collapsing across the previous 3 hours. If participants reported more than one conflict or drinking episode per day, both episodes were used as separate reports. This approach drastically increases the size of the data set while simultaneously decreasing variability, so we omitted the hours from 1 a.m. through 6 a.m., when virtually no conflict or alcohol use occurred. Analyses were conducted on a total possible 1,008 reports per person (56 days × 18 hours). More information about this approach is available in Testa and Derrick (2014).

We conducted multilevel modeling analyses using the multivariate feature in MLwiN 2.28 (Rasbash et al., 2013). Our analytic approach followed a three-level nested structure: within-day (hourly) effects were modeled at Level 1, within-couple (daily) effects were modeled at Level 2, between-couple (individual) effects were modeled at Level 3, and men’s and women’s reports of alcohol use in a given hour were treated as gender-specific repeated measures (i.e., multivariate outcomes). This method allows for straightforward tests of gender differences (a 1 df chi-square test). When the effects did not differ significantly by gender, we pooled the coefficients; otherwise, we reported the results for men and women separately.

We ran each set of analyses twice, once examining victim outcomes and once examining perpetrator outcomes. Alcohol use was treated as a dichotomous variable, so we used a binomial distribution with a logit link. To test our primary hypotheses, we included three indicators representing the occurrence of verbal IPA in the previous 3 hours (both-partner reports, victim-only reports, and perpetrator-only reports). We also included three indicators representing the occurrence of physical IPA in the previous 3 hours (both-partner reports, victim-only reports, and perpetrator-only reports).

In addition, we included several control variables: alcohol use within the previous 3 hours (a Level 1 variable, to control for autocorrelation); the partner’s alcohol use within the previous 3 hours (a Level 1 variable, to control for similarities in drinking); weekend (a Level 2 variable, dummy-coded 0 = Monday–Thursday and 1 = Friday–Sunday); the total number of alcohol use days and partner alcohol use days over the diary period (Level 3 variables, to control for overall levels of drinking); and the total number of both-partner reports, victim-only reports, and perpetrator-only reports of verbal and physical IPA per person over the diary period (Level 3 variables; to control for between-couple variability in IPA).

Initial analyses revealed no significant variability in alcohol use at Level 2 after we controlled for day of the week, so the intercept was treated as fixed at Level 2. It was allowed to vary randomly at Level 3. All Level 1 and Level 2 slopes were fixed-effect, dummy-coded variables (but weekend was grand mean centered); the three continuous Level 3 slopes were grand mean centered. Accordingly, the intercept represents the likelihood of alcohol use in a given hour when alcohol use, verbal IPA, and physical IPA had not occurred in the prior 3 hours, on a “typical” day of the week, for couples with average overall frequency of alcohol use and verbal and physical IPA.

Results

Hourly reports of IPA

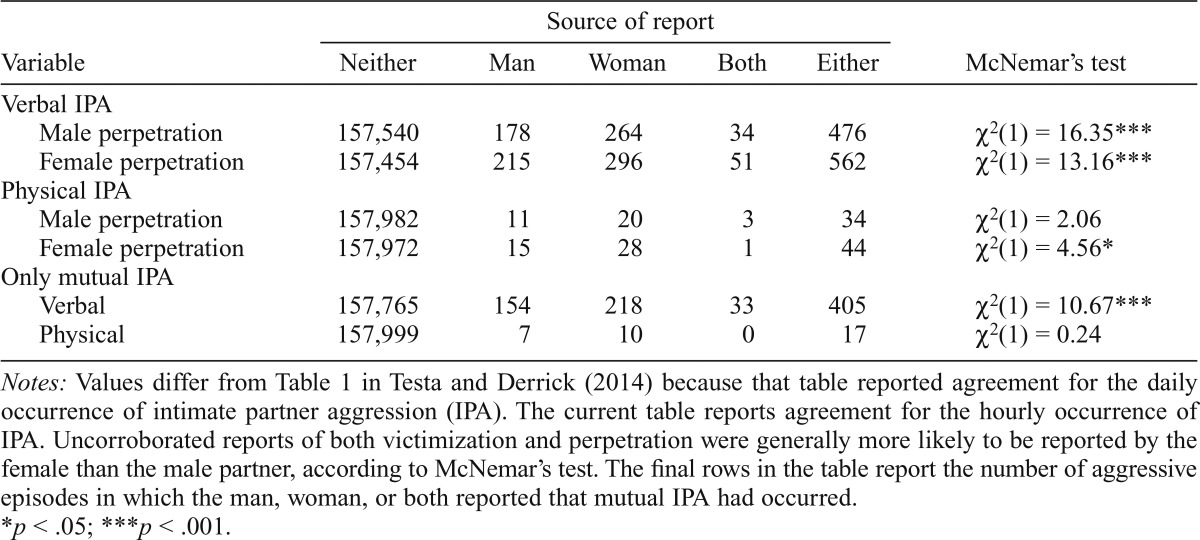

The first four rows in Table 1 present agreement between men and women regarding the occurrence of verbal and physical IPA. Men and women typically agreed that there had been no IPA, but there were some hours in which they agreed that it had occurred. It was more common for only one partner to report that IPA had occurred. Consistent with survey research (e.g., Testa et al., 2012) and our previous analyses from this sample (Testa & Derrick, 2014), uncorroborated reports of both victimization and perpetration were generally more likely to be reported by the female than by the male partner, according to McNemar’s test.

Table 1.

Men’s and women’s reports of verbal and physical aggression

| Source of report |

||||||

| Variable | Neither | Man | Woman | Both | Either | McNemar’s test |

| Verbal IPA | ||||||

| Male perpetration | 157,540 | 178 | 264 | 34 | 476 | χ2(1) = 16.35*** |

| Female perpetration | 157,454 | 215 | 296 | 51 | 562 | χ2(1) = 13.16*** |

| Physical IPA | ||||||

| Male perpetration | 157,982 | 11 | 20 | 3 | 34 | χ2(1) = 2.06 |

| Female perpetration | 157,972 | 15 | 28 | 1 | 44 | χ2(1) = 4.56* |

| Only mutual IPA | ||||||

| Verbal | 157,765 | 154 | 218 | 33 | 405 | χ2(1) = 10.67*** |

| Physical | 157,999 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 17 | χ2(1) = 0.24 |

Notes: Values differ from Table 1 in Testa and Derrick (2014) because that table reported agreement for the daily occurrence of intimate partner aggression (IPA). The current table reports agreement for the hourly occurrence of IPA. Uncorroborated reports of both victimization and perpetration were generally more likely to be reported by the female than the male partner, according to McNemar’s test. The final rows in the table report the number of aggressive episodes in which the man, woman, or both reported that mutual IPA had occurred.

p < .05;

p < .001.

Victim alcohol use

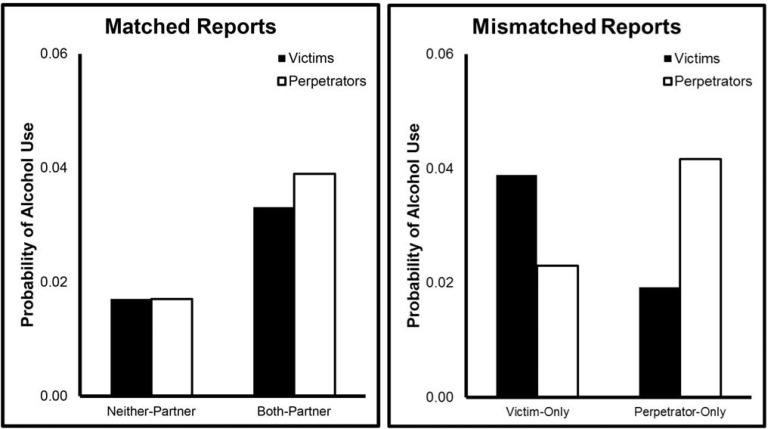

We expected that victims would be more likely to drink when they reported having received IPA in the previous 3 hours (both-partner/victim-only) than when they did not (perpetrator-only/neither-partner). Results for analyses examining the victim’s likelihood of drinking are presented in Table 2. Predicted values for verbal IPA for victim reports, pooled across gender, are depicted in Figure 1 in dark bars. The likelihood of consuming alcohol following the receipt of verbal IPA was about two times greater for both-partner reports and victim-only reports than for neither-partner reports. Alcohol use following verbal IPA did not differ between perpetrator-only reports and neither-partner reports. In follow-up analyses with recoded dummy variables, the likelihood of drinking after verbal IPA was greater following both-partner reports and victim-only reports compared with perpetrator-only reports (odds ratio [OR] = 1.90, 95% CI [1.01, 3.56], p = .046, and OR = 2.03, 95% CI [1.31, 3.13], p < .001, respectively). The difference between both-partner reports and victim-only reports was not significant (OR = 0.94, 95% CI [0.53, 1.68], p = .832). In other words, our hypothesis was supported for verbal IPA. Victims reported greater likelihood of consuming alcohol in a given hour when they reported having received verbal IPA in the previous 3 hours, independent of the perpetrator’s report. As shown in Table 2, receipt of physical IPA was not reliably associated with subsequent alcohol use; however, the small number of events reduces power to detect effects.

Table 2.

Perpetrator and victim alcohol use as a function of verbal IPA

| Victim alcohol use |

Perpetrator alcohol use |

|||

| Variable | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] |

| Intercept | 0.02*** | [0.02, 0.02] | 0.02*** | [0.02, 0.02] |

| Level 3 covariates (GMC) | ||||

| Victim frequency of alcohol use | 1.04*** | [1.04, 1.04] | 1.04*** | [1.04, 1.04] |

| Perpetrator frequency of alcohol use | 0.99*** | [0.99, 0.99] | 0.99*** | [0.99, 0.99] |

| Verbal: Both-partner reports | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.01] | 0.99 | [0.98, 1.01] |

| Verbal: Victim-only reports | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.00] | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.01] |

| Verbal: Perpetrator-only reports | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.00] | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.01] |

| Physical: Both-partner reports | 1.04 | [0.97, 1.11] | 1.02 | [0.95, 1.09] |

| Physical: Victim-only reports | 1.02 | [0.99, 1.04] | 0.99 | [0.96, 1.01] |

| Physical: Perpetrator-only reports | 1.00 | [0.98, 1.02] | 1.00 | [0.98, 1.03] |

| Level 2 covariates | ||||

| Weekday vs. weekend (GMC) | 1.58M*** | [1.47, 1.70]M | 1.57M*** | [1.46, 1.70]M |

| 1.84W*** | [1.70, 2.00]W | 1.84W*** | [1.70, 2.00]W | |

| Level 1 covariates | ||||

| Victim lagged alcohol use | 0.13*** | [0.11, 0.15] | 4.79*** | [4.44, 5.17] |

| Perpetrator lagged alcohol use | 4.79*** | [4.44, 5.17] | 0.13*** | [0.11, 0.15] |

| Level 1 verbal aggression | ||||

| Neither-partner reports | – | – | – | – |

| Both-partner reports | 1.98** | [1.18, 3.32] | 2.34*** | [1.39, 3.96] |

| Victim-only reports | 2.13*** | [1.61, 2.83] | 1.24 | [0.87, 1.76] |

| Perpetrator-only reports | 1.04 | [0.71, 1.53] | 2.26*** | [1.72, 2.99] |

| Level 1 physical aggression | ||||

| Neither-partner reports | – | – | – | – |

| Both-partner reportsa | 0.04 | [0.00, 3796] | 0.06 | [0.00, 640] |

| Victim-only reports | 0.61 | [0.17, 2.17] | 0.37 | [0.06, 2.16] |

| Perpetrator-only reports | 0.60 | [0.15, 2.37] | 0.76 | [0.25, 2.32] |

Notes: Frequency of alcohol use refers to the total number of days victims and perpetrators used alcohol during the 56-day diary period. Level 3 verbal and physical both-partner reports, victim-only reports, and perpetrator-only reports are grand-mean centered totals recorded for each couple during the 56-day diary period. Weekday is a dichotomous variable, originally coded 0 = Monday–Thursday, 1 = Friday–Sunday, but grand-mean centered for the analyses. Lagged alcohol use refers to the victims’ and perpetrators’ alcohol use in the previous 3 hours. Level 1 verbal aggression is a dummy-coded categorical variable reflecting agreement in verbal aggression in the previous 3 hours. Neither-partner reports serve as the reference group. Level 1 physical aggression is a dummy-coded categorical variable reflecting agreement in physical aggression in the previous 3 hours. Neither-partner reports serve as the reference group. Coefficients that differed significantly by gender are marked with subscripts. IPA = intimate partner aggression; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; M = men; W = women; GMC = grand-mean centered.

The 95% CI for the both-partner reports physical aggression indicator variable is very wide because there were few events (three male-perpetrated and one female-perpetrated).

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Probability of alcohol use as a function of self- and partner-reported victimization and perpetration. The dark bars portray effects on victim probability of using alcohol. The light bars portray effects on perpetrator probability of using alcohol. Reports in which partners agree regarding the occurrence of verbal intimate partner aggression (IPA) are depicted on the left. Reports in which partners disagree regarding the occurrence of verbal IPA are depicted on the right. Predicted values are pooled across gender.

We repeated these analyses using HED (defined as consuming greater than 4/5 drinks for women/men; Wechsler et al., 1995) and quantity as outcome variables (not shown). HED was treated as a dichotomous variable (0 = no HED, 1 = HED occurred). Quantity was treated as a continuous variable and was analyzed in a model using a normal distribution with an identity link. The pattern of results for HED and for quantity was the same as for any alcohol use, but the effects were not significant.

Perpetrator alcohol use

We expected that perpetrators would be more likely to drink when they reported having perpetrated IPA in the previous 3 hours (both-partner/perpetrator-only) than when they did not (victim-only/neither-partner). Results for analyses examining the perpetrator’s likelihood of drinking are presented in Table 2. Predicted values for verbal IPA for perpetrator reports, pooled across gender, are depicted in Figure 1 in light bars. The likelihood of consuming alcohol following the perpetration of verbal IPA was more than two times greater for both-partner reports and perpetrator-only reports than for neither-partner reports. Alcohol use following verbal IPA did not differ between victim-only reports and neither-partner reports. In follow-up analyses, the likelihood of drinking after verbal IPA was greater following both-partner reports and perpetrator-only reports than for victim-only reports (OR = 1.87, 95% CI [1.00, 3.47], p = .049, and OR = 1.83, 95% CI [1.22, 2.75], p = .004, respectively). The difference between both-partner reports and perpetrator-only reports was not significant (OR = 0.03, 95% CI [0.58, 1.85], p = .911). In other words, our hypothesis was supported for verbal IPA. Perpetrators were more likely to consume alcohol in a given hour when they reported having perpetrated verbal IPA in the previous 3 hours, independent of the victim’s report. As shown in Table 2, perpetration of physical IPA was not reliably associated with subsequent alcohol use.

We repeated these analyses using HED and quantity as outcome variables (not shown). Again, the pattern of results for both variables was the same as for any alcohol use, but the effects were not significant.

Supplemental analyses

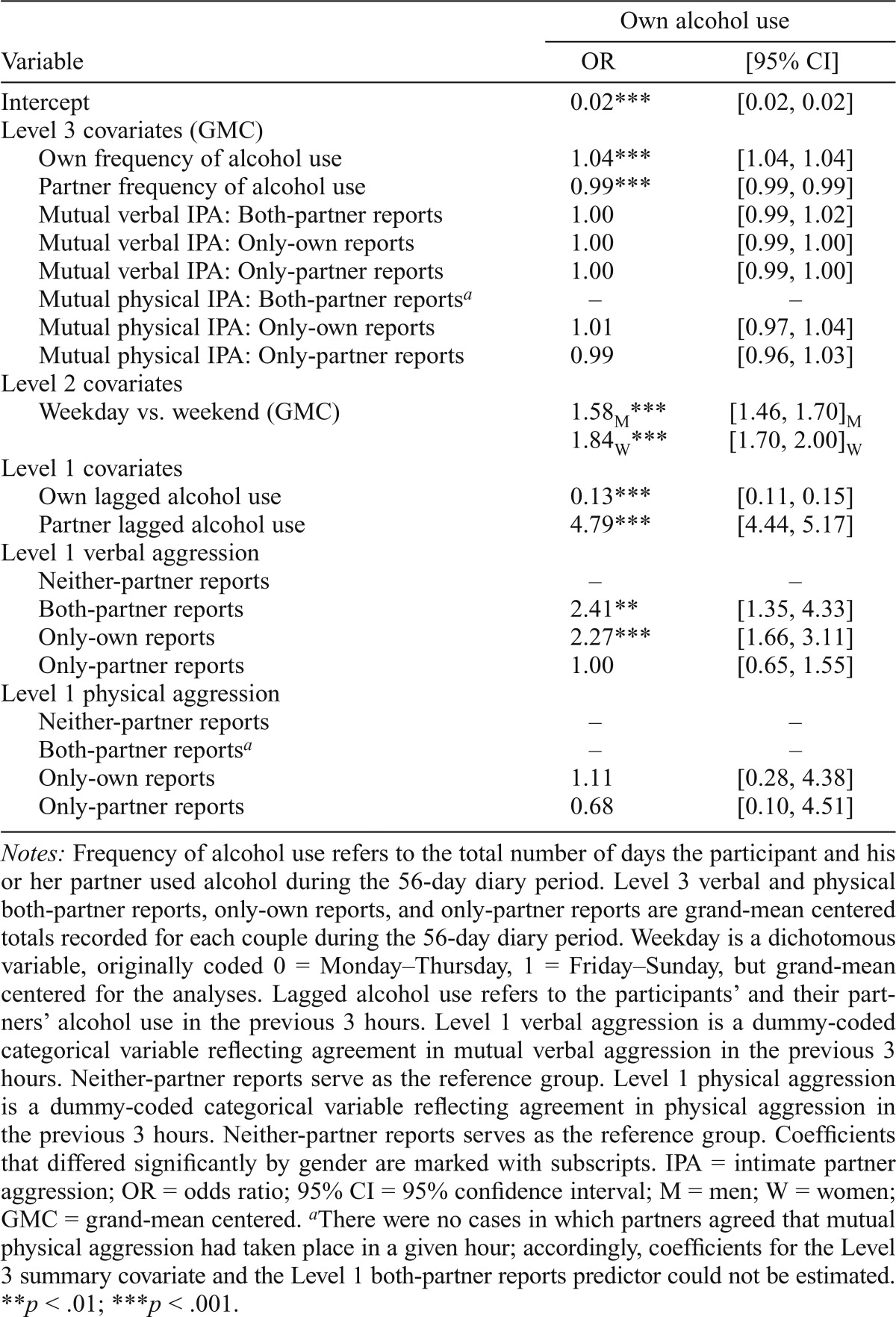

Although we found, as expected, that both victimization and perpetration contributed to subsequent drinking, victimization and perpetration often co-occur (Straus, 2008). Thus, we undertook supplemental analyses to explore whether the short-term effects of verbal IPA on drinking are apparent even when considering cases involving only mutual IPA (187 of 291 male-reported cases [64%]; 251 of 395 female-reported cases [64%]). As in the primary analyses, we also took into account the source of the report. As shown in the final rows of Table 1, there was substantial variation in the extent to which partners agreed that mutual verbal IPA had occurred. Men and women typically agreed that mutual verbal IPA had not occurred, but there were also some hours in which they agreed that it had occurred. It was more common for only one partner to report mutual verbal IPA in a given hour. Again, women provided more uncorroborated reports than men, according to McNemar’s test. We also present information for mutual physical IPA in Table 1, but the frequency of events is very low, and partners never agreed that mutual physical IPA had occurred in a given hour.

We examined the likelihood of consuming alcohol at a given time point as a function of self-only, partner-only, and both-partner reports of mutual IPA (Table 3). The likelihood of consuming alcohol following mutual verbal IPA was more than two times greater for those who reported mutual IPA (they provided the sole report or both partners reported) than when neither partner reported mutual IPA. This difference was not significant for those whose partner provided the sole report. Thus, even the effects of mutual verbal IPA on alcohol use are limited to those who actually report the occurrence of IPA.

Table 3.

Alcohol use as a function of mutual verbal IPA

| Own alcohol use |

||

| Variable | OR | [95% CI] |

| Intercept | 0.02*** | [0.02, 0.02] |

| Level 3 covariates (GMC) | ||

| Own frequency of alcohol use | 1.04*** | [1.04, 1.04] |

| Partner frequency of alcohol use | 0.99*** | [0.99, 0.99] |

| Mutual verbal IPA: Both-partner reports | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.02] |

| Mutual verbal IPA: Only-own reports | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.00] |

| Mutual verbal IPA: Only-partner reports | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.00] |

| Mutual physical IPA: Both-partner reportsa | – | – |

| Mutual physical IPA: Only-own reports | 1.01 | [0.97, 1.04] |

| Mutual physical IPA: Only-partner reports | 0.99 | [0.96, 1.03] |

| Level 2 covariates | ||

| Weekday vs. weekend (GMC) | 1.58M*** | [1.46, 1.70]M |

| 1.84W*** | [1.70, 2.00]W | |

| Level 1 covariates | ||

| Own lagged alcohol use | 0.13*** | [0.11, 0.15] |

| Partner lagged alcohol use | 4.79*** | [4.44, 5.17] |

| Level 1 verbal aggression | ||

| Neither-partner reports | – | – |

| Both-partner reports | 2.41** | [1.35, 4.33] |

| Only-own reports | 2 27*** | [1.66, 3.11] |

| Only-partner reports | 1.00 | [0.65, 1.55] |

| Level 1 physical aggression | ||

| Neither-partner reports | – | – |

| Both-partner reportsa | – | – |

| Only-own reports | 1.11 | [0.28, 4.38] |

| Only-partner reports | 0.68 | [0.10, 4.51] |

Notes: Frequency of alcohol use refers to the total number of days the participant and his or her partner used alcohol during the 56-day diary period. Level 3 verbal and physical both-partner reports, only-own reports, and only-partner reports are grand-mean centered totals recorded for each couple during the 56-day diary period. Weekday is a dichotomous variable, originally coded 0 = Monday–Thursday, 1 = Friday–Sunday, but grand-mean centered for the analyses. Lagged alcohol use refers to the participants’ and their partners’ alcohol use in the previous 3 hours. Level 1 verbal aggression is a dummy-coded categorical variable reflecting agreement in mutual verbal aggression in the previous 3 hours. Neither-partner reports serve as the reference group. Level 1 physical aggression is a dummy-coded categorical variable reflecting agreement in physical aggression in the previous 3 hours. Neither-partner reports serves as the reference group. Coefficients that differed significantly by gender are marked with subscripts. IPA = intimate partner aggression; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; M = men; W = women; GMC = grand-mean centered.

There were no cases in which partners agreed that mutual physical aggression had taken place in a given hour; accordingly, coefficients for the Level 3 summary covariate and the Level 1 both-partner reports predictor could not be estimated.

p < .01;

p < .001.

Discussion

In this study, experiencing verbal IPA was associated with subsequent alcohol use, supporting our hypotheses. Victims were more likely to drink when they reported having received verbal IPA in the previous 3 hours (both-partner/victim-only reports) than when they did not (perpetrator-only/neither-partner reports). Similarly, perpetrators were more likely to drink when they reported enacting verbal IPA in the previous 3 hours (both-partner/perpetrator-only reports) than when they did not (victim-only/neither-partner reports). It is possible that these findings reflect mutual aggression, given that the majority of individual reports indicate that there was aggression by both partners. However, even in cases where mutual IPA was reported, only the partner who reported it was subsequently more likely to drink. We found that experiencing verbal IPA increased the likelihood of consuming any alcohol, but not necessarily the amount of alcohol consumed. This finding suggests that people may have a drink to “calm down” after experiencing verbal IPA, consistent with an affect regulation model (e.g., Marlatt et al., 1975; Mohr et al., 2001), rather than “drowning the pain,” as might be predicted from a self-medication model (e.g., Øverup et al., 2015).

Importantly, however, only participants who reported having experienced IPA (as victim, as perpetrator, or as a mutual aggressor) demonstrated subsequent alcohol use, independent of their partner’s report. As we have argued previously (Derrick et al., 2014), the ability to report IPA requires that the reporter (a) interpret and encode the event as IPA, (b) retrieve the event from memory, and (c) overcome social desirability concerns to report the IPA (i.e., reporting bias). We believe that disagreement in our community sample was primarily attributable to differential interpretation of events, rather than memory or reporting bias. First, we used a daily diary study, so the effects of biased memory are reduced in comparison to retrospective surveys (Follingstad & Rogers, 2013). Second, reports of alcohol use were elevated only when people reported having experienced verbal IPA themselves and not when it was reported solely by their partner. If reporting discrepancies reflected underreporting because of social desirability bias, then presumably alcohol use would have been elevated after either partner had reported verbal IPA. Thus, the lack of agreement between partners does not reflect measurement error and, in fact, is not a weakness of the study. Rather, the current results suggest that IPA is, at least to some extent, “in the eye of the beholder.” It is constructed by the perceiver (whether victim or perpetrator) and has effects only when recognized as IPA.

Limitations

The couples in this sample are not representative of the larger population. Participants were selected for concordant heavier drinking in the absence of medical contraindications. Additionally, partners had been living together for an average of 6 years. Therefore, these couples probably established some type of equilibrium (perhaps through down-regulation with a drink after an argument) that allowed them to maintain the relationship over the longer term. The results of this study might not generalize to other couples; for example, those with particularly problematic conflict or drinking patterns likely would have separated or developed alcohol problems that would have rendered them ineligible for the current study. Furthermore, we lacked the power in our community sample to examine the effects of physical aggression on subsequent alcohol use (see also Parks et al., 2008; Shorey et al., 2016a). To adequately test this association, it may be necessary to recruit couples with a more frequent history of physical aggression.

Implications and future directions

The current results build on work demonstrating that stressful interpersonal experiences contribute to subsequent alcohol use (DeHart et al., 2008, 2009; Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Mohr et al., 2001; Parks et al., 2008). Growing evidence also demonstrates that alcohol use is a temporally proximal predictor of subsequent conflict and partner aggression (e.g., Crane et al., 2014; Shorey et al., 2014a, 2014b, 2015, 2016b; Testa & Derrick, 2017). Together, these data suggest that couples may enter a negative feedback loop in which relationship distress predicts alcohol use, and then alcohol use predicts additional relationship distress, and so forth (see Rodriguez & Derrick, 2017). This possibility is consistent with recent research demonstrating potential mechanisms by which drinking to cope may lead to more problematic alcohol use over time. Specifically, using alcohol to cope with stress serves to focus attention on the instigating stressors (through attention allocation) and to undermine more effective emotion regulation strategies (through ego depletion), thus exacerbating the initial distress (Armeli et al., 2014, 2016). Similarly, using alcohol to cope with relationship problems may exacerbate both relationship distress and alcohol use over time.

References

- Armeli S., O’Hara R. E., Covault J., Scott D. M., Tennen H. Episode-specific drinking-to-cope motivation and next-day stress-reactivity. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 2016;29:673–684. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2015.1134787. doi:10.1080/10615806.2015.1134787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S., O’Hara R. E., Ehrenberg E., Sullivan T. P., Tennen H. Episode-specific drinking-to-cope motivation, daily mood, and fatigue-related symptoms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:766–774. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.766. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., Field C., Ramisetty-Mikler S., Lipsky S. Agreement on reporting of physical, psychological, and sexual violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:1318–1337. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322181. doi:10.1177/0886260508322181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane C. A., Testa M., Derrick J. L., Leonard K. E. Daily associations among self-control, heavy episodic drinking, and relationship functioning: An examination of actor and partner effects. Aggressive Behavior. 2014;40:440–450. doi: 10.1002/ab.21533. doi:10.1002/ab.21533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart T., Tennen H., Armeli S., Todd M., Affleck G. Drinking to regulate negative romantic relationship interactions: The moderating role of self-esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:527–538. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2007.10.001. [Google Scholar]

- DeHart T., Tennen H., Armeli S., Todd M., Mohr C. A diary study of implicit self-esteem, interpersonal interactions and alcohol consumption in college students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:720–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.001. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick J. L., Testa M., Leonard K. E. Daily reports of intimate partner verbal aggression by self and partner: Short-term consequences and implications for measurement. Psychology of Violence. 2014;4:416–431. doi: 10.1037/a0037481. doi:10.1037/a0037481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad D. R., Rogers M. J. Validity concerns in the measurement of women’s and men’s report of intimate partner violence. Sex Roles. 2013;69:149–167. doi:10.1007/s11199-013-0264-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton H. R., DeHart T. Drinking to belong: The effect of a friendship threat and self-esteem on college student drinking. Self and Identity. 2016 Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/15298868.2016.1210539. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins R. L., Marlatt G. A. Fear of interpersonal evaluation as a determinant of alcohol consumption in male social drinkers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1975;84:644–651. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.84.6.644. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.84.6.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P. S., El-Sheikh M., Keiley M., Liao P. J. Longitudinal relations between marital aggression and alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:2–13. doi: 10.1037/a0013459. doi:10.1037/a0013459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A., Cooper M. L. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:1706–1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. doi:10.1177/0146167210388420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren K. P., Neighbors C., Blayney J. A., Mullins P. M., Kaysen D. Do drinking motives mediate the association between sexual assault and problem drinking? Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:323–326. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.009. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt G. A., Kosturn C. F., Lang A. R. Provocation to anger and opportunity for retaliation as determinants of alcohol consumption in social drinkers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1975;84:652–659. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.84.6.652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S. C., Collins R. L., Ellickson P. L. Cross-lagged relationships between substance use and intimate partner violence among a sample of young adult women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:139–148. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.139. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr C. D., Armeli S., Tennen H., Carney M. A., Affleck G., Hromi A. Daily interpersonal experiences, context, and alcohol consumption: Crying in your beer and toasting good times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:489–500. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.489. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Øverup C. S., DiBello A. M., Brunson J. A., Acitelli L. K., Neighbors C. Drowning the pain: Intimate partner violence and drinking to cope prospectively predict problem drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;41:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.006. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks K. A., Hsieh Y.-P, Bradizza C. M., Romosz A. M. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasbash J., Browne W. J., Healy M., Cameron B., Charlton C. London, England: Centre for Multilevel Modeling, University of Bristol; 2013. MLwiN: Version 2.28. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L. M., Derrick J. Breakthroughs in understanding addiction and close relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.011. Advance online publication. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J., Caetano R., Clark C. L. Agreement about violence in U.S. couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:457–470. doi:10.1177/0886260502017004007. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Brasfield H., Zapor H. Z., Febres J., Stuart G. L. The relation between alcohol use and psychological, physical, and sexual dating violence perpetration among male college students. Violence Against Women. 2015;21:151–164. doi: 10.1177/1077801214564689. doi:10.1177/1077801214564689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., McNulty J. K., Moore T. M., Stuart G. L. Being the victim of violence during a date predicts next-day cannabis use among female college students. Addiction. 2016a;111:492–498. doi: 10.1111/add.13196. doi:10.1111/add.13196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Moore T. M., McNulty J. K., Stuart G. L. Do alcohol and marijuana increase the risk for female dating violence victimization? A prospective daily diary investigation. Psychology of Violence. 2016b;6:509–518. doi: 10.1037/a0039943. doi:10.1037/a0039943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Stuart G. L., McNulty J. K., Moore T. M. Acute alcohol use temporally increases the odds of male perpetrated dating violence: A 90-day diary analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2014a;39:365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Stuart G. L., Moore T. M., McNulty J. K. The temporal relationship between alcohol, marijuana, angry affect, and dating violence perpetration: A daily diary study with female college students. Psychology ofAddictive Behaviors. 2014b;28:516–523. doi: 10.1037/a0034648. doi:10.1037/a0034648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:252–275. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.10.004. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A., Hamby S. L., Boney-McCoy S., Sugarman D. B. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi:10.1177/019251396017003001. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Crane C. A., Quigley B. M., Levitt A., Leonard K. E. Effects of administered alcohol on intimate partner interactions in a conflict resolution paradigm. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:249–258. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.249. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Derrick J. L. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. doi:10.1037/a0032988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Kubiak A., Quigley B. M., Houston R. J., Derrick J. L., Levitt A., Leonard K. E. Husband and wife alcohol use as independent or interactive predictors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:268–276. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.268. doi:10.15288/jsad.2012.73.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Leonard K. E. The impact of marital aggression on women’s psychological and marital functioning in a newlywed sample. Journal of Family Violence. 2001;16:115–130. doi:10.1023/A:1011154818394. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Livingston J. A., Leonard K. E. Women’s substance use and experiences of intimate partner violence: A longitudinal investigation among a community sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1649–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.040. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. E., Bacon A. K., Randall P. K., Brady K. T., See R. E. An acute psychosocial stressor increases drinking in nontreatment-seeking alcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2163-6. doi:10.1007/s00213-010-2163-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H., Dowdall G. W., Davenport A., Rimm E. B. A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:982–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.982. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]