Abstract

Objective:

Emotional disorders and alcohol use disorders (AUDs) frequently demonstrate significant 12-month and lifetime comorbid associations. This comorbidity has been incorporated into influential theories of addiction processes that posit direct or indirect causal associations between these disorder categories. There is currently no consensus, however, about the sequencing of these disorders. In this research, longitudinal data from a regionally representative community sample were used to evaluate whether emotional disorders constitute a proximal antecedent, concomitant, or short-term consequence of first episode (or index) AUDs.

Method:

Participants were 131 persons with index AUD episodes lasting 12 months or more and 131 matched controls. For each participant with an AUD, the presence or absence of an emotional disorder was coded for three time intervals: (a) the 12 months preceding full syndrome AUD episode onset; (b) the last 12 months of the AUD episode; and (c) the 12 months following complete symptom AUD episode offset. These intervals, referenced to participant age, were matched to those of control participants, and emotional disorder rate comparisons subsequently performed both within and between groups.

Results:

Findings indicated an absence of significant within- or between-subject differences in emotional disorder rates, suggesting that the association between AUDs and emotional disorders is neither directional nor systematic. There was also no indication that the length of the AUD episode increased risk for an emotional disorder in the year following AUD offset.

Conclusions:

Overall, this research suggests that emotional disorders are generally independent events in relation to the index AUD episode.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiological research has generally revealed significant associations between depressive and anxiety disorders (collectively emotional disorders) with alcohol abuse or dependence disorders (collectively alcohol use disorders, or AUDs; Boden & Fergusson, 2011; Grant et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 1996, 2005b; Swendsen et al., 1998). The lifetime prevalence of these disorders in the general population, when estimated retrospectively (Kessler et al., 2005a, 2011) or prospectively (Farmer et al., 2013a; Fergusson et al., 2009; Moffitt et al., 2010), suggests that they are common conditions. In addition to having descriptive significance, the commonality and comorbidity of AUDs with emotional disorders has theoretical relevance. Diagnostic comorbidity, for example, is often conceptualized in terms of direct causal relationships (e.g., where a secondary disorder is caused by a primary disorder) or indirect causal relationships (e.g., where a disorder is a secondary effect of a primary disorder) (Kessler & Price, 1993; Swendsen & Merikangas, 2000). An instance of the former would be a substance-induced depressive episode resulting from the neurotoxic effects of alcohol, with an example of the latter being harmful alcohol use to cope with uncomfortable emotions. Diagnostic comorbidity between AUDs and emotional disorders theoretically can arise also from the same psychobiological determinants (e.g., shared genetic predispositions, parental modeling processes, childhood trauma). Alternatively, emotional disorders and AUDs may be independent but frequently co-occur because they are common conditions among persons vulnerable to any form of psychopathology.

Some influential theoretical models of alcohol addiction hypothesize that emotional disorders and AUDs share direct or indirect causal relationships. Among these are models, such as the self-medication model, that propose emotional disorders are antecedents to problematic alcohol use (Khantzian, 1985; Quitkin et al., 1972). These models assume that emotional disorders are primary conditions and that AUDs are secondary conditions, whereby alcohol is sought and used primarily as a means of providing temporary relief from persistent negative moods. Alternatively, emotional disorders may be concomitants or consequences of problematic alcohol use (Fergusson et al., 2009; Merikangas et al., 1996; Swendsen et al., 1998) and, perhaps, have a role in AUD maintenance and relapse (Blume et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2008; Kushner et al., 2000). The allostatic (Koob & Le Moal, 2005, 2008) and substance-induced enhancement models of addiction (Kushner et al., 1990; Zvolensky et al., 2003), for example, suggest that multiple intoxication and withdrawal experiences increase susceptibility to anxious and depressed moods, and that these negative mood states, in turn, occasion subsequent substance use. Findings from retrospective (Falk et al., 2008; Merikangas et al., 1998) and prospective (Fergusson et al., 2009; Kushner et al., 1999; Zimmermann et al., 2003) studies as well as conclusions from literature reviews (e.g., Boden & Fergusson, 2011; Brown et al., 2008; Conner, 2011; Kushner et al., 2000; Raimo & Schuckit, 1998; Sher et al., 2005; Swendsen & Merikangas, 2000) further imply that emotional disorders may have complex relationships with AUDs that are, in part, influenced by maturational processes (e.g., changes in alcohol consumption patterns over the lifetime), cultural factors (e.g., cultural variations in patterns of alcohol consumption), and psychiatric history complexity (e.g., other co-occurring psychiatric disorders or the aggregation of disorders over the lifetime).

This study evaluated whether emotional disorders are proximal antecedents, concomitants, or short-term consequences of first episode (or index) AUDs. Earlier evaluations of the temporal associations between AUDs and emotional disorders include those from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP; Lewinsohn et al., 1993), a large and regionally representative community sample of an adolescent cohort followed longitudinally. This earlier research suggested that, by adolescence, other lifetime psychiatric conditions usually preceded rather than followed AUDs, including anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders (Rohde et al., 1996) but not depressive disorders, which were more likely to follow AUD episodes (Rohde et al., 1991). Similarly, when diagnostic categories from prior developmental periods were evaluated, only externalizing behavior disorders (disruptive behavior and non-alcohol substance use disorders) predicted AUD onsets during later developmental periods (Farmer et al., 2016; Rohde et al., 2001).

The present research, based on the OADP sample, is differentiated from our earlier work in four important ways. First, rather than evaluating lifetime or developmental period predictors of AUD onset, the present study is concerned with emotional disorder rates during the 12-month periods immediately before and after the onset and offset of the index AUD episode, respectively, as well as within the last 12 months of this episode. This study design is better suited for identifying possible causal associations between emotional disorders and AUDs. Second, we used a gender-matched control group from the same sample to evaluate if rates of emotional disorders in the AUD group differed from those without a history of AUD. Third, in addition to including a between-subjects component, the present research includes within-subjects analyses to evaluate possible differences in emotional disorder rates across the three time intervals examined. Fourth, we report data through age 30, thus better representing the age range within which a large majority of index AUD episodes occurs (Kessler et al., 2005a).

In addition to investigating emotional disorder and AUD sequencing, we also evaluated whether the duration of the index AUD episode was predictive of a greater risk for emotional disorders during the 12 months following the AUD offset. To the extent that emotional disorders following AUD episodes are consequences of extended alcohol misuse (e.g., because of the cumulative neurotoxic effects of alcohol intoxication, alcohol-related degradation of neurological systems that support reward processing, or alcohol-related functional impairments), the probability of an emotional disorder during the 12-month interval following AUD offset should theoretically be greater as a function of AUD episode duration (Wichers et al., 2010).

Method

Participants

The subsamples for this research were drawn from OADP data (Lewinsohn et al., 1993). Four diagnostic assessments (T1-T4) were conducted between ages 16 and 30. At T1, the sample consisted of 1,709 adolescents randomly selected from nine high schools that were representative of urban and rural districts in western Oregon. About 1 year later (T2), 1,507 (88%) of these persons were reassessed. At T3 (∼7 years after T2), a sampling stratification procedure was introduced whereby eligible participants included all persons with a positive history of a psychiatric diagnosis by T2 (n = 644) and a randomly selected subset of participants with no history of mental disorder by T2 (n = 457 of 863 persons). Of these 1,101 eligible persons, 941 (85%) completed T3. The T4 assessment period was conducted approximately 6 years after T3. From the 941 eligible persons who completed T3, 816 (87%) completed T4. These 816 participants (59% female, 89% White, 53% married) constitute the reference sample from which the subsamples for this research were drawn.

Participants were considered for study inclusion if they had at least one lifetime AUD episode by age 30. Because this study is concerned with the possible depressogenic or anxiogenic effects of AUDs, data from individuals who remained in their first AUD episode at the time of the last assessment (n = 40) were omitted, as were individuals who had index AUD episodes that lasted less than 12 consecutive months (n = 135). This latter inclusionary criterion was invoked to ensure that AUD cases were clinically significant and sufficiently severe. These criteria resulted in a sample of 131 persons (53 women, 78 men) with a history of an index AUD episode lasting 12 months or longer. Index AUD episodes included 75 cases with alcohol dependence (57%) and 56 with alcohol abuse (43%) diagnoses.

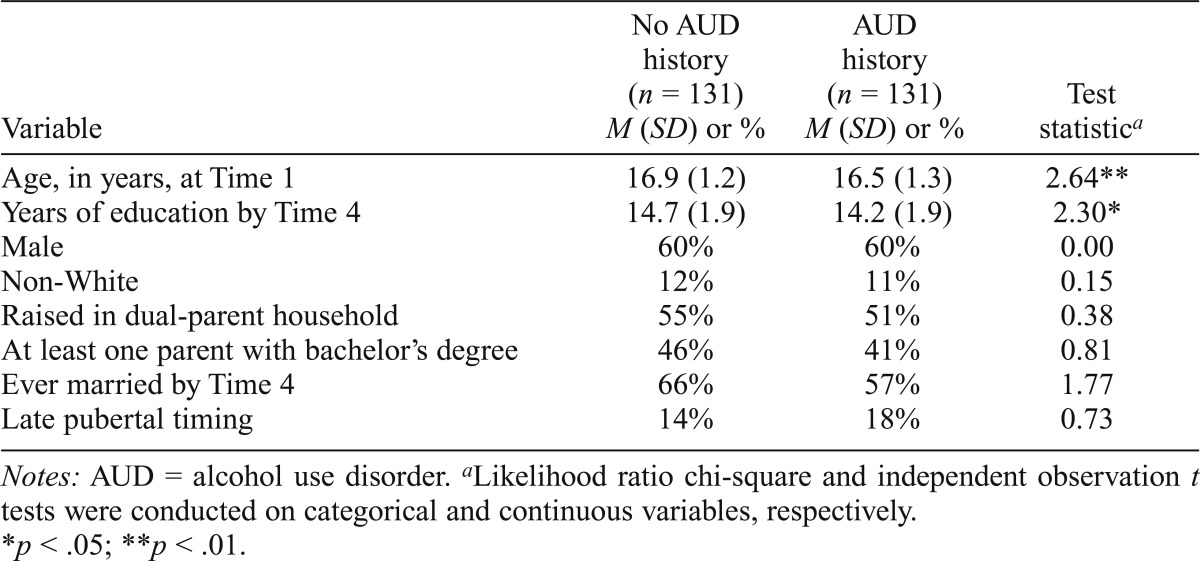

For each person with an index AUD episode of at least 12 months duration and who experienced a 12-month symptom-free recovery before reaching age 30.0, a control participant without an AUD history was randomly drawn from the OADP sample and matched on gender with the AUD participant. Subsample characteristics are compared in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics (n = 262)

| Variable | No AUD history (n = 131) M (SD) or % | AUD history (n = 131) M (SD) or % | Test statistica |

| Age, in years, at Time 1 | 16.9 (1.2) | 16.5 (1.3) | 2.64** |

| Years of education by Time 4 | 14.7 (1.9) | 14.2 (1.9) | 2.30* |

| Male | 60% | 60% | 0.00 |

| Non-White | 12% | 11% | 0.15 |

| Raised in dual-parent household | 55% | 51% | 0.38 |

| At least one parent with bachelor’s degree | 46% | 41% | 0.81 |

| Ever married by Time 4 | 66% | 57% | 1.77 |

| Late pubertal timing | 14% | 18% | 0.73 |

Notes: AUD = alcohol use disorder.

Likelihood ratio chi-square and independent observation t tests were conducted on categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

p <.05;

p <.01.

Measures

Diagnostic interviews.

During T1, T2, and T3, participants were interviewed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS), which combines features of the Epidemiologic and Present Episode versions (Chambers et al., 1985; Orvaschel et al., 1982). Follow-up assessments of disorders at T2 and T3 also involved the joint administration of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (LIFE; Keller et al., 1987) that, in conjunction with the K-SADS, provided detailed information related to the presence and course of disorders since participation in the previous diagnostic interview. The T4 assessment included administration of the LIFE and the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders– Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP; First et al., 1994). Although diagnostic categories were evaluated in accordance with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987), criteria at T1 and T2 and DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria at T3 and T4, there was sufficient additional symptom information collected during the first two assessments to permit DSM-IV-based AUD evaluations (Rohde et al., 2007). Consequently, all alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses are based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria.

For the analyses described below, we combined alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses into a single category (AUDs). Diagnostic agreement among raters for AUD diagnoses since the previous interview was substantial (mean k across waves = .77). Diagnostic variables related to depression were major depressive disorder (MDD), dysthymia (DYS), and, for DSM-IV-based assessments, substance-induced mood disorder. Diagnostic variables related to anxiety were the following disorders: generalized anxiety (GAD), social phobia (SOC), simple/specific phobia (PHOB), obsessive-compulsive (OCD), posttraumatic stress (PTSD), panic (PAN), agoraphobia without panic (AGR), and separation anxiety (SAD). Diagnostic reliability was moderate to excellent for individual disorder categories for which there were 10 or more positive diagnoses across interviewer and reliability assessors among interviews selected for reliability coding (mean k across waves: MDD = .84; DYS = .56, PTSD = .73, PHOB = .66, PAN = .81, SAD = .83; see Farmer et al., 2009, and Seeley et al., 2011, for details).

We also examined emotional disorder rates as a function of the duration of the index AUD episode. The episode duration variable refers to the length (in months) of the index AUD episode. In instances where both raters agreed on the occurrence of an index AUD episode, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) associated with duration judgments was .89. ICCs that indexed rater agreement for age (in months) of disorder onsets and offsets in instances where both raters agreed on the occurrence of an index AUD episode were similarly high (ICCs = .92 and .87 for disorder onsets and offsets, respectively).

Statistical analysis

Statistical procedures.

A mixed binomial logistic regression model with a logit link function and a first-order autoregressive covariance structure was used to test the significance of emotional disorder antecedents, concomitant, and consequences of AUDs. Models were fit using the GLIMMIX procedure with residual pseudo-likelihood estimation (SAS Institute Inc., Version 9.2, Cary, NC). All analyses incorporated sampling weights to account for the stratified sampling procedure implemented at T3. To avoid increased type I error rates associated with multiple statistical tests, we applied the Benjamini-Hochberg correction within families of planned contrasts and reported adjusted p values (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

The parameters of the index AUD episode were first determined for each diagnosed case (i.e., participant’s age in months at time of episode onset and offset). The 12-month period before the disorder onset is referred to as Interval 1 (I1), the last 12 months during which the participant was in an AUD episode as Interval 2 (I2), and the 12-month recovery period following disorder offset as Interval 3 (I3). In the present research, recovery is defined by the complete absence of AUD symptoms for a continuous 12-month period, with “disorder offset” or the beginning of the I3 interval commencing with the first month of this 12-month period. To illustrate, if a participant experienced the first AUD episode at month 228 (age 19.0) and this episode persisted to month 252 (age 21.0), months 240 to 252 would be referred to as I2. The 12 months before the onset of the index AUD episode (month 215 to 227) was referred to as I1, and the 12 months following the offset of I2 constituted I3 (month 253 to 265). The decision to analyze the last 12 months of the index episode was guided by statistical considerations (e.g., the I2 interval should be as long as the I1 and I3 intervals to avoid spurious interactions with time) and data interpretability whereby the timeframe definition for the I2 interval is consistent across participants. A gender-matched control participant from the OADP sample without an AUD history was subsequently selected, and intervals based on the same age-months as the AUD participant were aligned, whereby depressive and anxiety disorders were separately coded for their presence or absence within each corresponding interval. The statistical model included the main effects of AUD group and time interval as well as the AUD Group × Time interaction. Least squares mean estimates were used in planned between- and within-group contrasts. Age at T1 and years of education, mean-centered, were entered as covariates to adjust for observed between-group differences (Table 1).

Risk categories associated with emotional disorders as a function of alcohol use disorders.

Emotional disorders were considered proximal antecedent risk factors of AUDs if between-group contrasts (AUD vscontrol) indicated higher rates of disorder episodes at I1 for the AUD group relative to controls. If, however, group differences were observed at each interval (I1, I2, and I3), whereby the AUD group had consistently higher rates of disorders than controls, this pattern would suggest that emotional disorders were a chronic risk factor associated with AUDs.

Emotional disorders were considered concomitants of AUDs if (a) between-group contrasts indicated no differences in rates of disorder episodes at I1 and I3 and greater rates of disorder episodes during I2 in the AUD group relative to controls, and (b) within-group contrasts indicated participants with AUDs experienced greater rates disorder episodes at I2 compared with I1 and I3.

Emotional disorders were considered short-term consequences of AUDs if (a) between-group contrasts indicated no differences in rates of disorder episodes at I1 and greater rates of disorder episodes during I2 and I3 for the AUD group relative to controls, and (b) within-group contrasts indicated participants with AUDs experienced higher rates of disorder episodes at I2 compared with I1 and equal or greater rates of disorder episodes during I3 when compared with I2. Within-group contrasts of emotional disorder rates for the control group were expected to be equal across intervals (i.e., I1 = I2 = I3) because intervals were selected based on characteristics of AUD-positive matched cases and are consequently pseudo-random intervals within the time span studied.

Results

Domain-based analyses: Evaluation of emotional disorders in relation to the index alcohol use disorder episode

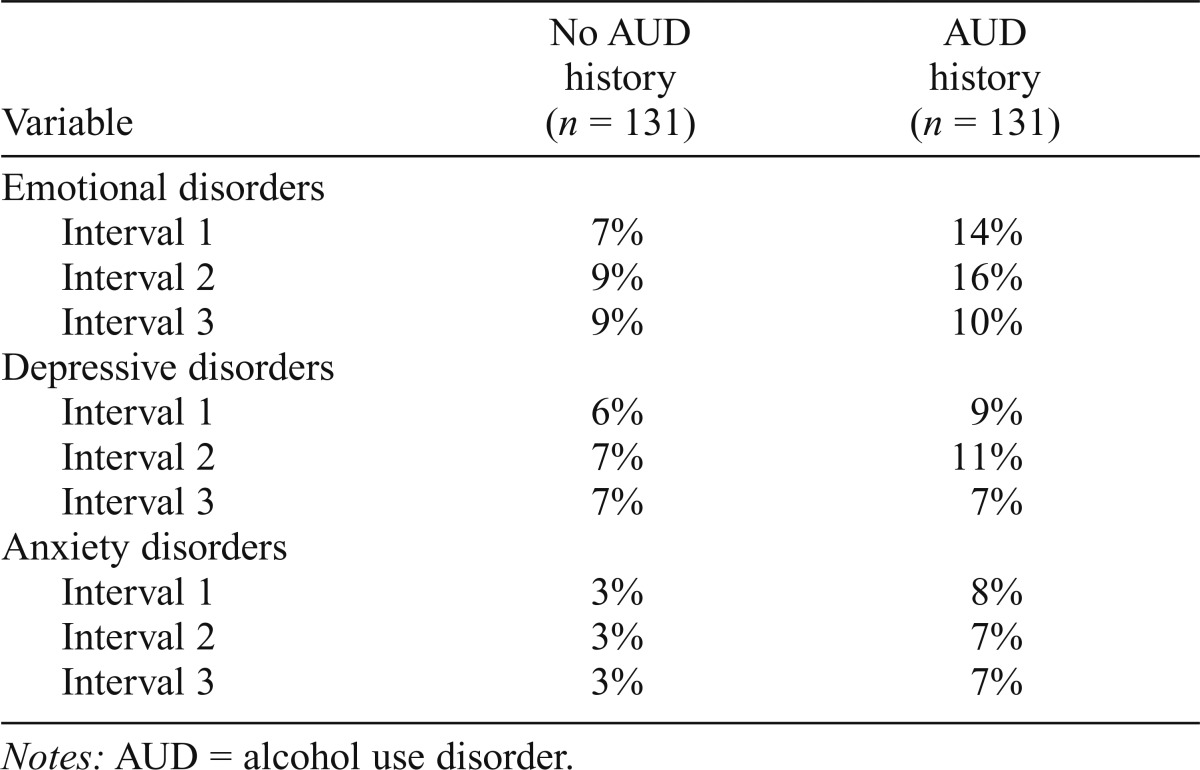

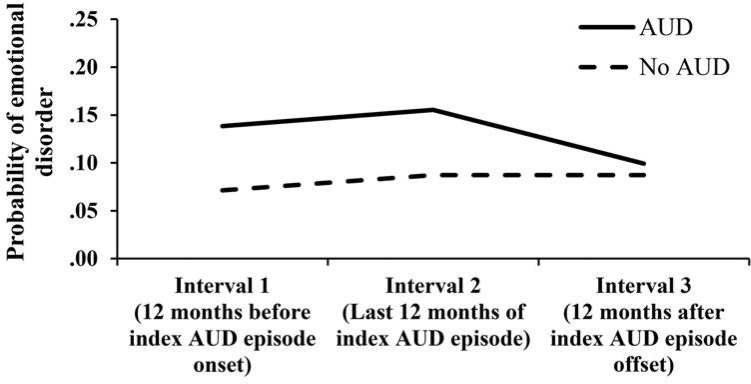

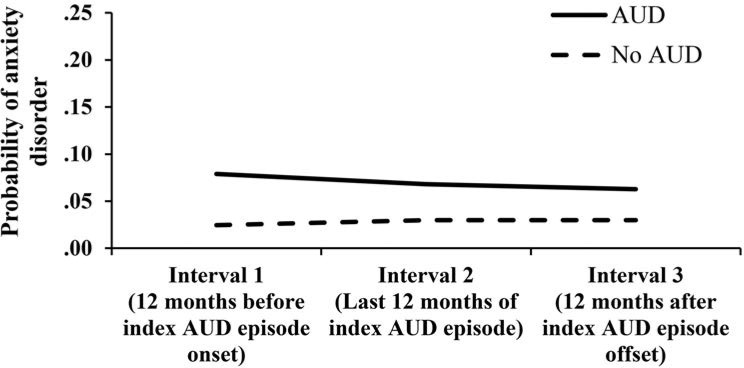

Table 2 presents observed incidence rates of emotional, depressive, and anxiety disorders separately for the AUD and control groups within each interval. Figure 1 illustrates model-implied probabilities of experiencing an emotional disorder (i.e., either a depressive or anxiety disorder) during I1, I2, and I3, separately for each group.

Table 2.

Observed incidence rates of emotional, depressive, and anxiety disorders within study intervals

| Variable | No AUD history (n = 131) | AUD history (n = 131) |

| Emotional disorders | ||

| Interval 1 | 7% | 14% |

| Interval 2 | 9% | 16% |

| Interval 3 | 9% | 10% |

| Depressive disorders | ||

| Interval 1 | 6% | 9% |

| Interval 2 | 7% | 11% |

| Interval 3 | 7% | 7% |

| Anxiety disorders | ||

| Interval 1 | 3% | 8% |

| Interval 2 | 3% | 7% |

| Interval 3 | 3% | 7% |

Notes: AUD = alcohol use disorder.

Figure 1.

Model-implied probabilities of experiencing an emotional disorder episode during Intervals 1, 2, and 3: Probability of emotional disorders at each interval as a function of alcohol use disorder (AUD) history

Between-group contrasts.

For the I1 comparison, there was not a significant group difference in emotional disorder rates (odds ratio [OR] = 2.09, 95% CI [0.90, 4.87]; Benjamini–Hochberg–corrected p value [pBH] = .153). Similarly, there was not a significant effect for group at I2 (OR = 1.93, 95% CI [0.88, 4.23]; pBH = .153) or at I3 (OR = 1.15, 95% CI [0.49, 2.71]; pBH=.742).

Within-group contrasts.

For each within-subjects test (i.e., I1 vs. I2, I1 vs. I3, I2 vs. I3), rates of emotional disorders were not significantly different across the three time intervals for the AUD group (pBHs ≥ .289) or the control group (pBHs ≥ .910).

Depressive disorder subdomain analyses: Evaluation of depressive disorders in relation to the index alcohol use disorder episode

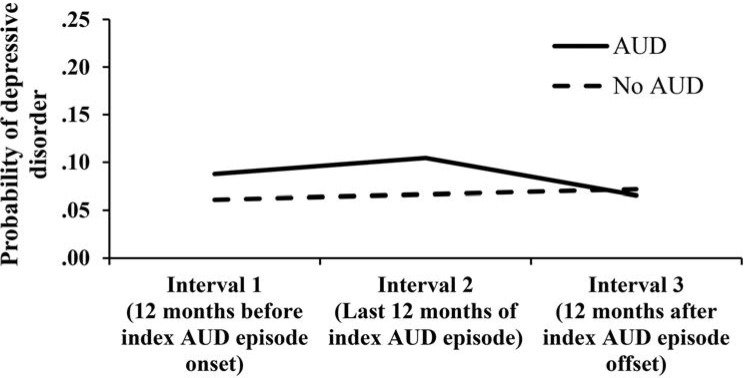

Figure 2 illustrates model-implied probabilities of experiencing depressive episodes during I1, I2, and I3 for each group.

Figure 2.

Model-implied probabilities of experiencing depressive disorder episodes during Intervals 1, 2, and 3: Probability of depressive disorders at each interval as a function of alcohol use disorder (AUD) history

Between-group contrasts.

Rates of depressive disorders were separately compared for the AUD and matched control groups for each time interval. For the I1 comparison, there was not a significant group effect (OR = 1.48, 95% CI [0.57, 3.83]; pBH = .631). Nonsignificant comparisons between the AUD group and controls were also observed at I2 (OR = 1.63, 95% CI [0.66, 4.02]; pBH = .631) and at I3 (OR = 0.91, 95% CI [0.35, 2.41]; pBH = .846).

Within-group contrasts.

Rates of depressive disorders were not significantly different across the three time intervals for the AUD group (pBHs ≥ .623) or the control group (pBHs ≥ .857).

Anxiety disorder subdomain analyses: Evaluation of anxiety disorders in relation to the index alcohol use disorder episode

Figure 3 illustrates model-implied probabilities of experiencing anxiety disorder episodes during I1, I2, and I3.

Figure 3.

Model-implied probabilities of experiencing anxiety disorder episodes during Intervals 1, 2, and 3: Probability of anxiety disorders at each interval as a function of alcohol use disorder (AUD) history

Between-group contrasts.

For the I1 comparison, there was not a significant group difference in anxiety disorder rates (OR = 3.40, 95% CI [0.92, 12.56];pBH = .200). Similarly, there was not a significant effect for group at I2 (OR = 2.38, 95% CI [0.68, 8.31]; pBH = .227) or at I3 (OR = 2.18, 95% CI [0.61, 7.74]; pBH = .227).

Within-group contrasts.

Rates of anxiety disorders were not significantly different across the three time intervals for the AUD group (pBHs ≥ .681) or the control group (pBHs ≥ .993).

Emotional disorders as a function of alcohol use disorder episode duration

In a logistic regression analysis restricted to participants with AUD histories, the duration of the index AUD episode (M = 125.0 weeks, SD = 65.3 for females; M = 172.9 weeks, SD = 106.4 for males) was not a significant predictor of emotional disorder presence versus absence during the I3 interval (p = .809) after controlling for gender and I1 emotional disorders. In two comparable subdomain analyses, the duration of the index AUD episode was similarly evaluated as a predictor of the presence versus absence of an I3 depressive and anxiety domain disorder after controlling for gender and I1 disorders from the same domain. AUD episode duration was not a significant predictor of depressive or anxiety disorders during the I3 interval (p = .776 and .723, respectively).

Discussion

This case-controlled longitudinal research investigation with a regionally representative community sample identified no reliable directional or systematic associations between index AUD episodes and emotional disorders. The absence of significant effects implies that emotional disorders are independent of the index AUD episode during the year before AUD episode onset, the last year of the AUD episode, and the year after AUD episode offset among persons from the community.

Findings obtained in this research suggest limitations of influential models of alcohol addiction, including the self-medication model (Khantzian, 1985; Quitkin et al., 1972), the substance-induced enhancement model (Kushner et al., 1990; Zvolensky et al., 2003), and the allostatic model (Koob & Le Moal, 2005; 2008), each of which imply causal associations between emotional disorders and AUDs. All of the ORs for the reported contrasts fell within the small-to-moderate effect range for dichotomous predictors (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001) except for the OR resulting from the between-groups contrast for the I1 interval for anxiety disorders, which denoted a moderate-to-large effect. Despite the magnitude of this effect, this OR was not statistically significant because of a combination of limited sample size and low emotional disorder rates that theory implies should be higher. Correspondingly, the explanatory power of the self-medication theory based on antecedent anxiety disorders is, at best, limited to a very small proportion of cases that subsequently develop AUDs. Based on the overall pattern of findings from this study, if negative affect has a reliable role as an antecedent, concomitant, or consequence of AUDs, it would appear to be at a level below the threshold of a diagnosable disorder.

The findings reported here also depart somewhat from those previously reported in treatment samples. In treatment studies, for example, findings are mixed with respect to the self-medication hypothesis (e.g., McCarthy et al., 2005; Schinka et al., 1994; Tomlinson et al., 2006; Weiss et al., 1992), similarly suggesting that this account might apply only to a relatively small proportion of individuals with AUDs. Likewise, depressed mood in some studies has been associated with a resumption of alcohol use following treatment (Curran et al., 2000; de Timary et al., 2008; Tomlinson et al., 2006; Witkiewitz & Villarroel, 2009). The propensity to experience negative affect during recovery, however, usually diminishes rapidly as the period of abstinence increases (Brown & Schuckit, 1988; Davidson, 1995; de Timary et al., 2008; Driessen et al., 2001), suggesting that negative moods might be an acute consequence immediately following alcohol cessation that does not rise to the level of a diagnosable disorder. Another possible explanation for some differences in findings reported here and in treatment studies is that treatment samples likely include a preponderance of persons who have had multiple prior AUD episodes (Wang et al., 2005) and disorder comorbidities (Berkson, 1946; Low et al., 2008; Merikangas et al., 1996), and consist of individuals who are otherwise unrepresentative of persons who experience AUDs in the general population (Merikangas et al., 1994; Swendsen & Merikangas, 2000). Problem drinking and emotional disturbance in the present research were also operationalized at the disorder level of description, whereas the treatment studies summarized above often assessed anxiety or depressed mood with dimensional measures.

The absence of a reliable association between emotional disorders and the course of AUDs in this research raises questions about the nature of the relationship between these two sets of conditions. In the full OADP sample (n = 816), tetrachoric correlations that index the association of lifetime AUDs with lifetime emotional disorders, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders were .18, .19, and .18, respectively. These findings are consistent with those recently reported from a large nationally representative sample that showed either no or modest associations between AUDs and emotional disorders in well-controlled adjusted analyses (Grant et al., 2015). Population-based multivariate research that used past-year (Slade & Watson, 2006; Vollebergh et al., 2001) and lifetime diagnostic data derived retrospectively (Kessler et al., 2011; Krueger, 1999; Røysamb et al., 2011) and prospectively (Caspi et al., 2014; Farmer et al., 2013b) have also failed to identify latent factors that account for both AUDs and individual emotional disorders apart from a general psychopathology factor. In addition, concurrent mood and anxiety symptoms or disorders have not been distinguishing features of different longitudinally based trajectory groups defined by varying problems with alcohol (Hill et al., 2000; Jacob et al., 2005, 2009). Chassin et al. (2002), however, reported comparatively low levels of depression among males in their persistent drinking group, which was the trajectory group characterized by the most severe alcohol-related problems. In the aggregate, emotional disorders may, in most instances, be contextually unrelated to the occurrence and course of AUDs, particularly for first-episode AUDs. As psychiatric disorders histories become more pronounced, however, greater comorbid associations between AUDs and other psychiatric conditions become increasingly more likely (Farmer et al., 2013a).

Findings from the present research must be considered alongside some study limitations. First, the age range in the present research spanned childhood through age 30, a period within which a large majority of index AUD episode onsets are likely to occur (Kessler et al., 2005a). It is possible, however, that AUDs occasioned by stress or negative emotion are more common among older individuals. Existing research has been mixed as to whether emotional problems are more common among those with earlier versus later AUD onset ages (e.g., Cloninger, 1987; Johnson et al., 2000). Consequently, the generalizability of findings observed here to those with initial AUD onsets after age 30 is uncertain. Second, although the index AUD cases studied in this research were severe based on their duration (i.e., ≥12 months), they were not further characterized by associated symptomatology that might also convey severity (e.g., cases where withdrawal symptomatology was reported). It is possible that an alternative AUD phenotype, one in which physical symptoms related to prolonged alcohol use are evident, might produce different findings. Third, our analyses were conducted at domain (i.e., emotional disorders) and subdomain (i.e., depressive and anxiety disorders) levels collapsed over individual disorders, which could obscure unique associations that individual disorders within domains have with the course of AUDs. Among the anxiety disorders, for example, PTSD has been found to be a risk factor for subsequent substance abuse (Stewart, 1996). Fourth, although diagnostic interviewers and reliability raters substantially agreed about the timing of AUD episode onset and offset, the ability of participants to accurately recall this information is uncertain. Fifth, given the relatively low base rates of emotional disorders observed, the ability to detect statistically significant effects may have been enhanced had sample sizes been larger.

In summary, no reliable evidence was obtained that emotional disorders constitute proximal antecedents, concomitants, or short-term consequences of first-episode AUDs in a representative community sample. Furthermore, index AUD episode length was not associated with a greater or lesser risk for emotional disorders during the 12 months following AUD offset. Future research might evaluate whether emotional difficulties below the threshold of a diagnosable disorder demonstrate similar patterns as those observed here.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 3rd ed., rev. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A new and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:1289–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Biometrics Bulletin. 1946;2:47–53. doi:10.2307/3002000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume A. W., Schmaling K. B., Marlatt G. A. Revisiting the self-medication hypothesis from a behavioral perspective. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:379–384. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(00)80048-6. [Google Scholar]

- Boden J. M., Fergusson D. M. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011;106:906–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. A., McGue M., Maggs J., Schulenberg J., Hingson R., Swartzwelder S., Murphy S. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics, 121, Supplement. 2008;4:S290–S310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. A., Schuckit M. A. Changes in depression among abstinent alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1988;49:412–417. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.412. doi:10.15288/jsa.1988.49.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A., Houts R. M., Belsky D. W., Goldman-Mellor S. J., Harrington H., Israel S., Moffitt T. E. The p factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2:119–137. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473. doi:10.1177/2167702613497473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers W. J., Puig-Antich J., Hirsch M., Paez P., Ambrosini P. J., Tabrizi M. A., Davies M. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview. Test-retest reliability of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children, present episode version. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L., Pitts S. C., Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:67–78. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C. R. Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science. 1987;236:410–416. doi: 10.1126/science.2882604. doi:10.1126/science.2882604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner K. R. Clarifying the relationship between alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011;106:915–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03385.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran G. M., Flynn H. A., Kirchner J., Booth B. M. Depression after alcohol treatment as a risk factor for relapse among male veterans. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;19:259–265. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00107-0. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K. M. Diagnosis of depression in alcohol dependence: Changes in prevalence with drinking status. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166:199–204. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.2.199. doi:10.1192/bjp.166.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Timary P., Luts A., Hers D., Luminet O. Absolute and relative stability of alexithymia in alcoholic inpatients undergoing alcohol withdrawal: Relationship to depression and anxiety. Psychiatry Research. 2008;157:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen M., Meier S., Hill A., Wetterling T., Lange W., Junghanns K. The course of anxiety, depression and drinking behaviours after completed detoxification in alcoholics with and without comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2001;36:249–255. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.3.249. doi:10.1093/alcalc/36.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D. E., Yi H. Y., Hilton M. E. Age of onset and temporal sequencing of lifetime DSM-IV alcohol use disorders relative to comorbid mood and anxiety disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.022. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer R. F., Gau J. M., Seeley J. R., Kosty D. B., Sher K. J., Lewinsohn P. M. Internalizing and externalizing disorders as predictors of alcohol use disorder onset during three developmental periods. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;164:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.021. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer R. F., Kosty D. B., Seeley J. R., Olino T. M., Lewinsohn P. M. Aggregation of lifetime Axis I psychiatric disorders through age 30: Incidence, predictors, and associated psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013a;122:573–586. doi: 10.1037/a0031429. doi:10.1037/a0031429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer R. F., Seeley J. R., Kosty D. B., Lewinsohn P. M. Refinements in the hierarchical structure of externalizing psychiatric disorders: Patterns of lifetime liability from mid-adolescence through early adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:699–710. doi: 10.1037/a0017205. doi:10.1037/a0017205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer R. F., Seeley J. R., Kosty D. B., Olino T. M., Lewinsohn P. M. Hierarchical organization of Axis I psychiatric disorder comorbidity through age 30. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013b;54:523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.12.007. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Boden J. M., Horwood L. J. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:260–266. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M. B., Spitzer R. L., Gibbon M., Williams J. B. W. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department; 1994. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders, Non-Patient Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Stinson F. S., Dawson D. A., Chou S. P., Dufour M. C., Compton W., Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Goldstein R. B., Saha T. D., Chou S. P., Jung J., Zhang H., Hasin D. S. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K. G., White H. R., Chung I. J., Hawkins J. D., Catalano R.F. Early adult outcomes of adolescent binge drinking: Person- and variable-centered analyses of binge drinking trajectories. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:892–901. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02071.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T., Bucholz K. K., Sartor C. E., Howell D. N., Wood P, K. Drinking trajectories from adolescence to the mid-forties among alcohol dependent males. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:745–755. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.745. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T., Koenig L. B., Howell D. N., Wood P, K., Haber J. R. Drinking trajectories from adolescence to the fifties among alcohol-dependent men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:859–869. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.859. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. A., Cloninger C. R., Roache J. D., Bordnick P. S., Ruiz P. Age of onset as a discriminator between alcoholic subtypes in a treatment-seeking outpatient population. American Journal on Addictions. 2000;9:17–27. doi: 10.1080/10550490050172191. doi:10.1080/10550490050172191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M. B., Lavori P. W., Friedman B., Nielsen E., Endicott J., Mc-Donald-Scott P., Andreasen N. C. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K. R., Walters E. E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005a;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Chiu W. T., Demler O., Merikangas K. R., Walters E. E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005b;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Nelson C. B., McGonagle K. A., Edlund M. J., Frank R. G., Leaf P. J. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. doi:10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Ormel J., Petukhova M., McLaughlin K. A., Green J. G., Russo L. J., Ustun T. B. Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:90–100. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Price R. H. Primary prevention of secondary disorders: A proposal and agenda. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:607–633. doi: 10.1007/BF00942174. doi:10.1007/BF00942174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian E. J. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G. F., Le Moal M. Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the dark side of drug addiction. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1442–1444. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1442. doi:10.1038/nn1105-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G. F., Le Moal M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R. F. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner M. G., Abrams K., Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:149–171. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00027-6. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner M. G., Sher K. J., Beitman B. D. The relation between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:685–695. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.685. doi:10.1176/ajp.147.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner M. G., Sher K. J., Erickson D. J. Prospective analysis of the relation between DSM-III anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:723–732. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P. M., Hops H., Roberts R. E., Seeley J. R., Andrews J. A. Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:133–144. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey M. W., Wilson D. B. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. Practical meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Low N. C., Cui L., Merikangas K. R. Community versus clinic sampling: Effect on the familial aggregation of anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:884–890. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.011. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy D. M., Tomlinson K. L., Anderson K. G., Marlatt G. A., Brown S. A. Relapse in alcohol- and drug-disordered adolescents with comorbid psychopathology: Changes in psychiatric symptoms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:28–34. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.28. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., Angst J., Eaton W., Canino G., Rubio-Stipec M., Wacker H., Kupfer D. J. Comorbidity and boundaries of affective disorders with anxiety disorders and substance misuse: Results of an international task force. British Journal of Psychiatry, 168, Supplement. 1996;30:58–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., Mehta R. L., Molnar B. E., Walters E. E., Swendsen J. D., Aguilar-Gaziola S., Kessler R. C. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: Results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00076-8. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., Risch N. J., Weissman M. M. Comorbidity and co-transmission of alcoholism, anxiety and depression. Psychological Medicine. 1994;24:69–80. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700026842. doi:10.1017/S0033291700026842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T. E., Caspi A., Taylor A., Kokaua J., Milne B. J., Polanczyk G., Poulton R. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:899–909. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991036. doi:10.1017/S0033291709991036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H., Puig-Antich J., Chambers W., Tabrizi M. A., Johnson R. Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-e. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1982;21:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60944-4. doi:10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quitkin F. M., Rifkin A., Kaplan J., Klein D. F. Phobic anxiety syndrome complicated by drug dependence and addiction. A treatable form of drug abuse. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;27:159–162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750260013002. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750260013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimo E. B., Schuckit M. A. Alcohol dependence and mood disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:933–946. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00068-9. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P., Lewinsohn P. M., Kahler C. W., Seeley J. R., Brown R. A. Natural course of alcohol use disorders from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00020. doi:10.1097/00004583-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P., Lewinsohn P. M., Seeley J. R. Comorbidity of unipolar depression: II. Comorbidity with other mental disorders in adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:214–222. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.2.214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P., Lewinsohn P. M., Seeley J. R. Psychiatric comorbidity with problematic alcohol use in high school students. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:101–109. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00018. doi:10.1097/00004583-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P., Lewinsohn P. M., Seeley J. R., Klein D. N., Andrews J. A., Small J. W. Psychosocial functioning of adults who experienced substance use disorders as adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.155. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Røysamb E., Kendler K. S., Tambs K., Ørstavik R. E., Neale M. C., Ag-gen S. H., Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The joint structure of DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:198–209. doi: 10.1037/a0021660. doi:10.1037/a0021660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinka J. A., Curtiss G., Mulloy J. M. Personality variables and self-medication in substance abuse. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1994;63:413–22. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_2. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley J. R., Kosty D. B., Farmer R. F., Lewinsohn P. M. The modeling of internalizing disorders on the basis of patterns of lifetime comorbidity: Associations with psychosocial functioning and psychiatric disorders among first-degree relatives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:308–321. doi: 10.1037/a0022621. doi:10.1037/a0022621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher K. J., Grekin E. R., Williams N. A. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T., Watson D. The structure of common DSM-IV and ICD-10 mental disorders in the Australian general population. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1593–1600. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008452. doi:10.1017/S0033291706008452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S. H. Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:83–112. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.83. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J. D., Merikangas K. R. The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:173–189. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00026-4. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J. D., Merikangas K. R., Canino G. J., Kessler R. C., Rubio-Stipec M., Angst J. The comorbidity of alcoholism with anxiety and depressive disorders in four geographic communities. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90058-x. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson K. L., Tate S. R., Anderson K. G., McCarthy D. M., Brown S. A. An examination of self-medication and rebound effects: Psychiatric symptomatology before and after alcohol or drug relapse. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.028. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh W. A. M., Iedema J., Bijl R. V., de Graaf R., Smit F., Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The NEMESIS study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. S., Berglund P., Olfson M., Pincus H. A., Wells K. B., Kessler R. C. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R. D., Griffin M. L., Minn S. M. Drug abuse as selfmedication for depression: An empirical study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1992;18:121–129. doi: 10.3109/00952999208992825. doi:10.3109/00952999208992825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M., Geschwind N., van Os J., Peeters F. Scars in depression: Is a conceptual shift necessary to solve the puzzle? Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:359–365. doi: 10.1017/s0033291709990420. doi:10.1017/S0033291709990420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K., Villarroel N. A. Dynamic association between negative affect and alcohol lapses following alcohol treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:633–644. doi: 10.1037/a0015647. doi:10.1037/a0015647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P., Wittchen H. U., Höfler M., Pfister H., Kessler R. C., Lieb R. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders: A 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:1211–1222. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008158. doi:10.1017/S0033291703008158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky M. J., Schmidt N. B. Panic disorder and smoking. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:29–51. doi:10.1093/clipsy.10.1.29. [Google Scholar]