Abstract

Objective:

Building on the extensive research literature demonstrating that increasing alcohol prices reduces excessive alcohol consumption and related harms, this article presents the results of a 50-state review of local authority to tax alcohol in the United States.

Method:

Between 2013 and 2015, legal databases and government websites were reviewed to collect and analyze relevant statutes, ordinances, and case law. Results reflect laws in effect as of January 1, 2015.

Results:

Nineteen states allow local alcohol taxation, although 15 of those have one or more major restrictions on local authority to tax. The types of major restrictions are (a) restrictions on the type of beverage and alcohol content that can be taxed, (b) caps on local alcohol taxes, (c) restrictions on the type of retailer where taxes can be imposed,(a) restrictions on jurisdictions within the state that can levy taxes, and (b) requirements for how tax revenue can be spent.

Conclusions:

The number and severity of restrictions on local authority to tax alcohol vary across states. Previous research has shown that increases in alcohol taxes can lead to reduced excessive alcohol consumption, which provides public health and economic benefits. Taxes can also provide funds to support local prevention and treatment services. Local alcohol taxes therefore present an important policy opportunity, both in states that restrict local authority and in states where local authority exists but is underused.

An extensive body of research literature demonstrates that increasing alcohol prices reduces excessive alcohol consumption and related harms (Elder et al., 2010; Wagenaar et al., 2010). The Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2010) recommends “increasing taxes on the sale of alcoholic beverages, on the basis of strong evidence of this policy’s effectiveness in reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms” (p. 230). This recommendation was based on a systematic review that found that a 10% increase in the price of alcohol resulted in a 7% reduction in alcohol consumption across all beverage types (e.g., beer, wine, distilled spirits) (Elder et al. 2010). The review also concluded that higher prices or taxes were consistently related to fewer alcohol-related harms, such as alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes (Elder et al., 2010).

Alcohol taxes in the United States have substantially declined in real dollars at the federal and state level (Kerr et al., 2013), making alcoholic beverages more affordable. This leaves a large gap between the economic cost of excessive alcohol consumption in the United States (about $2.05 per drink in 2010) (Sacks et al., 2015) and total federal and state taxes on alcoholic beverages (about $0.14 per drink in 2011) (Naimi, 2011). By comparison, federal and state taxes accounted for $1.00 per drink in 1950 (in 2011 dollars) (Kerr et al., 2013).

Local governments may also have the authority to use taxes and fees to raise alcohol prices. Where localities have such authority, local tax increases may be easier to enact and can help communities offset the erosion in alcohol taxes at the federal and state levels. Local tax campaigns can also complement other community efforts to reduce excessive alcohol use.

Types of alcohol taxes

Alcohol taxes can be imposed based either on volume (e.g., $1.00 per gallon), referred to as an excise tax, or on cost (e.g., 5% of the retail price of an alcoholic beverage), referred to as an ad valorem tax (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, n.d.). An ad valorem tax is a type of sales tax that applies only to specific products, such as alcoholic beverages. Unlike excise taxes, ad valorem taxes are not eroded by inflation because they increase with price. These two types of taxes may be imposed simultaneously or separately. Together, both types are important strategies for reducing excessive alcohol consumption, as indicated by recent research showing that combining excise and ad valorem tax measures led to higher elasticity in reducing binge drinking compared with only an excise tax (Xuan et al., 2015).

Fees may be used to pay for costs to government associated with licensing and regulating a business (including paying for services provided by government). Like taxes, fees can affect the price of alcohol, depending on how they are structured. For example, a fee can be imposed on a volume basis (i.e., based on how much alcohol a wholesaler distributes to retailers). States are generally more likely to allow local governments to impose fees than taxes, as fees are often considered integral to local governments’ ability to regulate land use.

State preemption doctrine and local authority to impose alcohol taxes

The preemption doctrine refers to the authority of higher levels of government to mandate or restrict the practices of lower levels of government (Gorovitz et al., 1998; Mosher & Treffers, 2013). When preemption exists, lower levels of government are precluded from deviating from the policies mandated by higher levels of government (Diller, 2007). The federal government’s ability to preempt state and local action is limited by the U.S. Constitution; under the 10th Amendment, all authority not expressly granted to the federal government is delegated to the states (U.S. Const. amend. X). This includes the authority to regulate the price and availability of alcohol; in fact, the 21st Amendment explicitly grants states the power to regulate alcohol within their borders (U.S. Const. amend. XXI).

All states have comprehensive legal structures for regulating alcoholic beverages and imposing and collecting alcohol taxes, but states vary widely in the extent to which they allow local governments control over sales and taxation of alcoholic beverages.

This article describes the types of alcohol taxes in the United States, with a focus on local policy options. It then analyzes the effect of state preemption on local alcohol tax authority and the extent to which local authority is used in states that grant it. Finally, it discusses the implications of these findings for state and local governments as well as for public health agencies and practitioners.

Method

In Phase 1 of a four-phase methodology, we searched Westlaw, an online research database of primary and secondary legal sources. We identified laws granting local alcohol tax authority by conducting state-by-state searches of relevant constitutional provisions, statutes, regulations, and case law. We also searched for relevant state law on the websites of state Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) agencies, the entities responsible for implementing and enforcing ABC laws.

We then classified laws granting local authority to generate revenue from alcohol sales as allowing either taxes or fees. Alcohol taxes were defined as legal provisions whose primary purpose is to generate revenue on alcohol sales, without reference to costs associated with regulating alcohol. Fees were defined as legal provisions whose primary purpose is to collect revenue as part of a regulatory structure. Fees reference costs associated with alcohol sales (impact fees) or services to industry members (including license fees, which typically reference the licensee’s privilege to do business).

The subsequent analysis of state laws was restricted to those states that allow local governments to independently tax alcoholic beverages; laws regarding fees are complex and are beyond the scope of this research.

Results from Phase 1 showed that ad valorem taxes may be permitted through state sales tax laws even though they may not be referenced in the ABC codes. Accordingly, in Phase 2 we conducted an independent 50-state review of each state’s sales tax laws to determine (a) whether local governments could impose sales taxes and (b) if yes, whether localities could impose a separate sales tax on alcoholic beverages, exclusive of other products (i.e., independent of a broader sales tax), thereby meeting the definition of an ad valorem tax on alcoholic beverages.

In a small number of states, the sales tax provisions do not specify whether local governments are allowed to impose a separate ad valorem tax on alcoholic beverages, suggesting that this taxing authority might exist. For those states, we conducted extensive case law research in Westlaw to determine whether courts had found that local governments have this authority and, if so, to what extent.

If case law research did not clarify whether there was local taxing authority, we identified the state’s 10 largest cities, defined by size of population as recorded in the 2010 census. To locate the sales tax provisions of the 10 largest cities’ municipal codes, we searched Municode (an online library of municipal codes [Tallahassee, FL; www.municode.com]) and cities’ websites; where necessary, we obtained copies of the relevant code provisions directly from the city. We reviewed the alcohol code and sales tax code of each city to determine whether a local alcohol tax existed.

We then conducted case law research using Westlaw to determine whether any local alcohol tax we identified had been challenged in court. If at least 1 of the 10 largest cities imposed an alcohol-specific local tax that had not been challenged in court, the state was categorized as permitting local alcohol ad valorem taxes. Whenever state laws governing local alcohol taxes were unclear, at least 1 city in the state was found to have imposed a local alcohol tax. Thus, only states with a definitive constitutional or statutory preemption provision were classified as preempting local taxation.

During Phase 3, we determined what type of restrictions on local tax authority existed in each state. We reviewed the tax codes of each state with local taxing authority to determine the extent to which that authority (for either excise taxes or ad valorem taxes) was subject to any of the following five restrictions:

(a) Restrictions on the type of beverage and alcohol content that could be taxed. A state may permit local taxes only on specific types of beverages (e.g., beer, wine, or distilled spirits) and/or beverages with a specific alcohol content.

(b) Limits or caps on the amount of tax. A state may permit local alcohol taxes but place a ceiling on the amount of the tax.

(c) Restrictions on the type of retail establishment subject to the tax. Local taxes may be allowed only on specific types of businesses (e.g., on alcohol sales at restaurants but not gas stations).

(d) Restrictions on which local jurisdictions were allowed to impose the tax. A state may allow only certain cities or counties to impose alcohol taxes.

(e) Requirements regarding how the tax revenues can be spent. A state may establish parameters on (i.e., earmark) how the local government spends the revenue (e.g., by permitting it to be spent only on tourism-related activities).

States may only allow local governments to enact one of the two types of taxes (i.e., excise or ad valorem). This was not treated as a separate restriction since either type of tax can achieve public health benefits.

In Phase 4, we reviewed the municipal codes of the 10 largest cities (according to 2010 census data) in states with local taxing authority to determine whether they had levied a local excise and/or ad valorem tax on alcoholic beverages and, if so, the size of the tax imposed by beverage type. We omitted states that strictly limit which local jurisdictions have local tax authority. We also omitted five states with very low caps (1% or less ad valorem tax) for the purposes of researching whether the 10 largest cities had exercised their authority to enact a local tax, given that the very low cap did not justify the extensive resources needed to determine whether the cities had a tax.

In the few cases where researchers had divergent interpretations of the legal materials, we conducted additional research or consulted key informants to reach consensus. Data were collected and analyzed between 2013 and 2015; results reflect state laws in effect as of January 1, 2015.

Results

Status of local alcohol tax authority

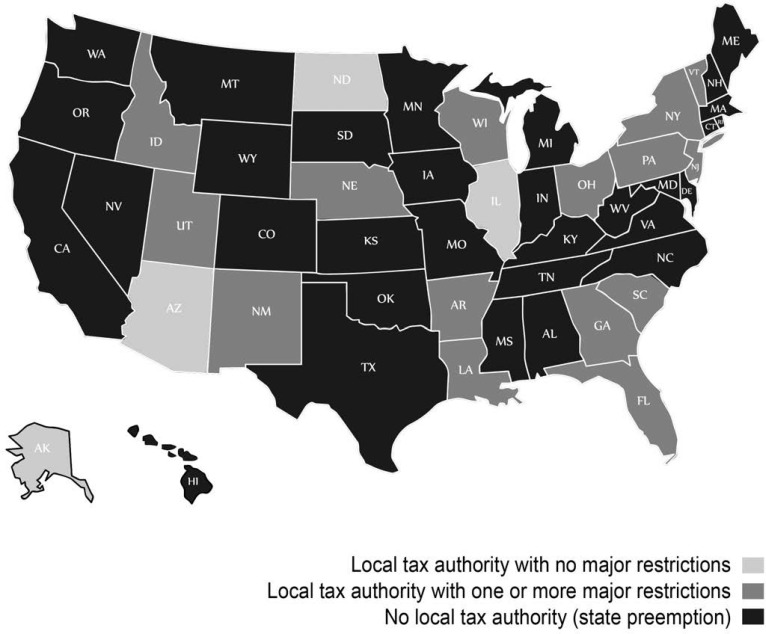

As of January 1, 2015, 31 states (62%) preempt local alcohol tax authority; the remaining 19 (38%) grant at least some alcohol tax authority to local governments (Figure 1). Of the 19 states allowing local taxation, 3 (16%) (Alaska, Georgia, and Illinois) allow local governments to impose both ad valorem and excise taxes; 15 (79%) allow local governments to impose either ad valorem or alcohol-specific excise taxes but not both; and one (5%) (Louisiana) only allows the imposition of excise taxes.

Figure 1.

Local tax authority, January 2015

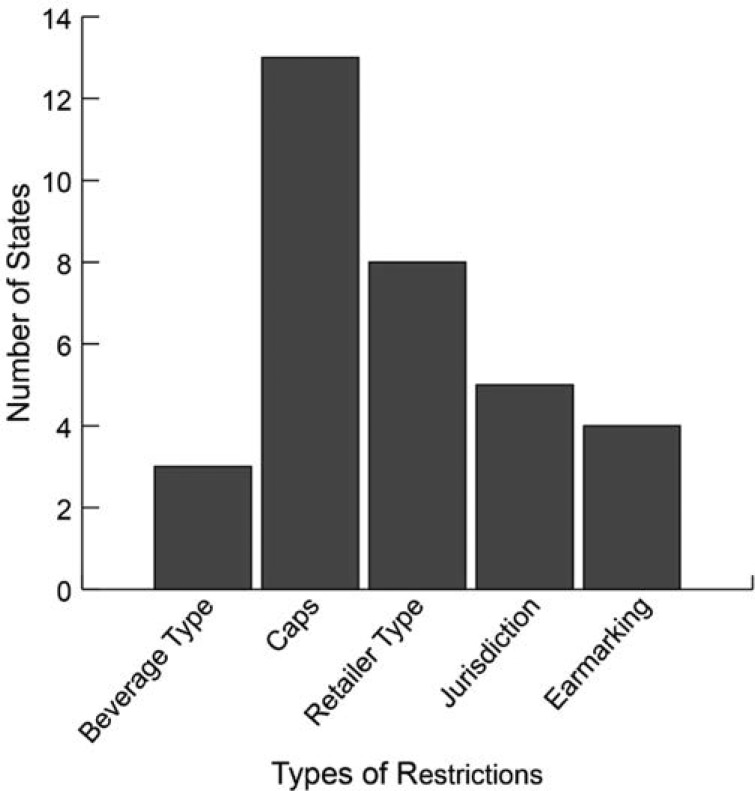

Four (21%) of the 19 states have no major restrictions on local tax authority, whereas 15 (79%) have one or more of the five major restrictions. A limit or cap on the local tax is the most common restriction, followed by a restriction on the type of retailer taxed (e.g., on-premises vs. off-premises) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Types of restrictions on tax authority among the states that permit local taxation, January 2015

Limits or caps.

Of the 19 states with local tax authority, 6 (32%) do not place caps on local tax levels. The remaining 13 (68%) impose caps ranging from 0.5% (Wisconsin) to 14% (Arkansas, distilled spirits) for ad valorem taxes, and from $0.05/gallon (Louisiana, beverages with an alcohol content no more than 6%) to $1.00/gallon (New York, distilled spirits) for excise taxes (Table 1). Four states (Florida, Ohio, Utah, and Vermont) impose a 1% ad valorem tax cap. Louisiana’s cap apparently does not apply to New Orleans, although our research did not identify legislation exempting New Orleans from the cap.

Table 1.

Restrictions on local alcohol taxing authority in states that permit local taxation, January 2015*

| Major restrictions |

|||||

| State | Beverages that may be taxed | Cap on amount of tax (per gal. or ad valorem) | Type of retail sales that may be taxed | Limits on use of tax revenue | Limits on which local governments have tax authority |

| Alaska | All | None | All | None | None |

| Arizona | All | None | All | None | None |

| Arkansas | All | Beer & wine: 10% Spirits: 14% | On premises | None | None |

| Florida | All | 1%a | On premises | Tourism, emergency, or homeless services | Noneb |

| Georgia | Distilled spirits & wine | Spirits & wine: $0.83/gal. On-premises spiritsc: 3% | All | None | None |

| Idaho | All | None | On premises | None | Resort cities with less than 10,000 population |

| Illinois | All | None | All | None | None |

| Louisiana | 6% or less ABV (limitation does not apply to New Orleans) | $0.05/gal. (cap does not apply to New Orleans) | All | None | None |

| Nebraska | All | None | On premises | None | None |

| New Jersey | All | 3% | On premises | None | Resort cities bordering Atlantic Ocean |

| New Mexico | All | 6% | All | Education, treatment, prevention | McKinley County |

| New York | Beer & distilled spirits, 24% ABV or above | Beer: $0.12/gal. Spirits: $1/gal. | All | None | New York Cityd |

| North Dakota | All | None | All | None | None |

| Ohio | All | 1% | All | None | Noneb |

| Pennsylvania | All | 10% | All | Transit systems | Allegheny Countye |

| All | 10% | All | N/A | Philadelphiae | |

| South Carolina | All | 2% | On-premises | Tourism-related activities | None |

| Utah | All | 1% | Restaurants | None | Noneb |

| Vermont | All | 1% | All | None | None |

| Wisconsin | All | 0.5% | On-premises within exposition districts | None | None |

Notes: Gal. = gallon; ABV = alcohol by volume; N/A = not applicable.

Florida also allows localities to impose a tax of up to 2% on sales of alcoholic beverages at hotels and motels.

Only counties are able to enact a local tax. This was not treated as a limitation because it is not jurisdiction specific.

Georgia allows localities to impose an additional tax of up to 3% on sales of spirits at on-premises retailers.

NewYork state law allows local taxation in cities with a population of 1 million or more, which functionally includes only New York City.

Pennsylvania allows local taxation only in two types of localities: counties with a population of 800,000 to 1,499,999 (functionally includes only Allegheny County), and cities with a population of 1 million or more (functionally includes only Philadelphia).

Table includes only states that permit at least some local taxing authority.

Type of retailer.

Of the 19 states with local tax authority, 11 (58%) allow localities to impose taxes on all retailers. The remaining eight limit local alcohol taxes to only on-premises retailers (Table 1). Three of these eight states impose additional limitations: New Jersey allows localities to impose an alcohol tax only on sales in on-premises establishments associated with tourism, Utah only allows local taxes on restaurants, and Wisconsin limits tax authority to on-premises retailers within exposition districts (special districts established for certain types of development).

Beverage type and alcohol content.

Sixteen states have no restrictions on beverage type or alcohol type. The remaining three limit the specific beverage types that can be taxed. Georgia allows local taxes only on wine and distilled spirits (localities must also collect a state-mandated beer tax, but they cannot additionally tax beer) (Table 1). New York allows local taxes on beer and distilled spirits with an alcohol content of 24% or more and prohibits wine taxes. This limitation also functionally prohibits beer taxes, because almost all beer brands have an alcohol content of less than 24%. Louisiana limits the tax authority of all cities except New Orleans to beverages with an alcohol content of 6% or less (treated here as functionally permitting taxes only on beer). New Orleans is permitted to tax all beverage types.

Restrictions on jurisdictions.

Of the 19 states, 14 (74%) allow all local jurisdictions to impose alcohol taxes, although the taxing authority of some local jurisdictions may be limited by state laws regarding the authority of and interaction between jurisdictions. The remaining five states limit which local governments have the authority to impose a tax (Table 1). Three of these five grant local taxing authority to only one or two jurisdictions (McKinley County, New Mexico; New York City, New York; and Philadelphia and Allegheny County, Pennsylvania). The other two place other restrictions on local taxing authority: New Jersey only allows local taxes in resort cities bordering the Atlantic Ocean, and Idaho restricts local taxing authority to resort cities with populations of 10,000 or fewer residents.

Restrictions on how tax revenues are expended.

Of the 19 states, 15 (79%) place no limits on how local alcohol tax revenue can be spent. The remaining four specify how revenues can be spent: Florida (tourism and emergency/homeless services), New Mexico (educational programs, alcohol and drug abuse prevention and treatment), Pennsylvania (transit systems), and South Carolina (tourism-related activities) (Table 1).

Other restrictions.

Four states impose additional restrictions that do not appear to limit local governments significantly in imposing alcohol taxes. Arizona does not permit local taxes that are “so burdensome as to become prohibitory to businesses,” a phrase not defined further. (Because it does not establish a firm ceiling, Arizona is treated as a no-cap state.) Local jurisdictions in Alaska can enact an alcohol tax only if they have also enacted another sales tax, such as a tobacco tax or a hotel tax (i.e., they cannot single out alcohol as the sole commodity to be taxed). Nebraska and Utah require the tax to apply to all sales in on-premises alcohol retailers, including sales of food and nonalcoholic beverages.

Use of local alcohol tax authority

The analysis of local tax authority use was limited to states where local jurisdictions have broad tax authority. Of the 19 states with local taxing authority, 9 (47%) allow local taxes of more than 1% of retail sales and do not limit tax authority by jurisdiction. Five (26%) limit tax authority by jurisdiction, and five (26%) have caps of 1% or less. (As noted above, those with caps of 1% or less were omitted from this portion of the analysis.)

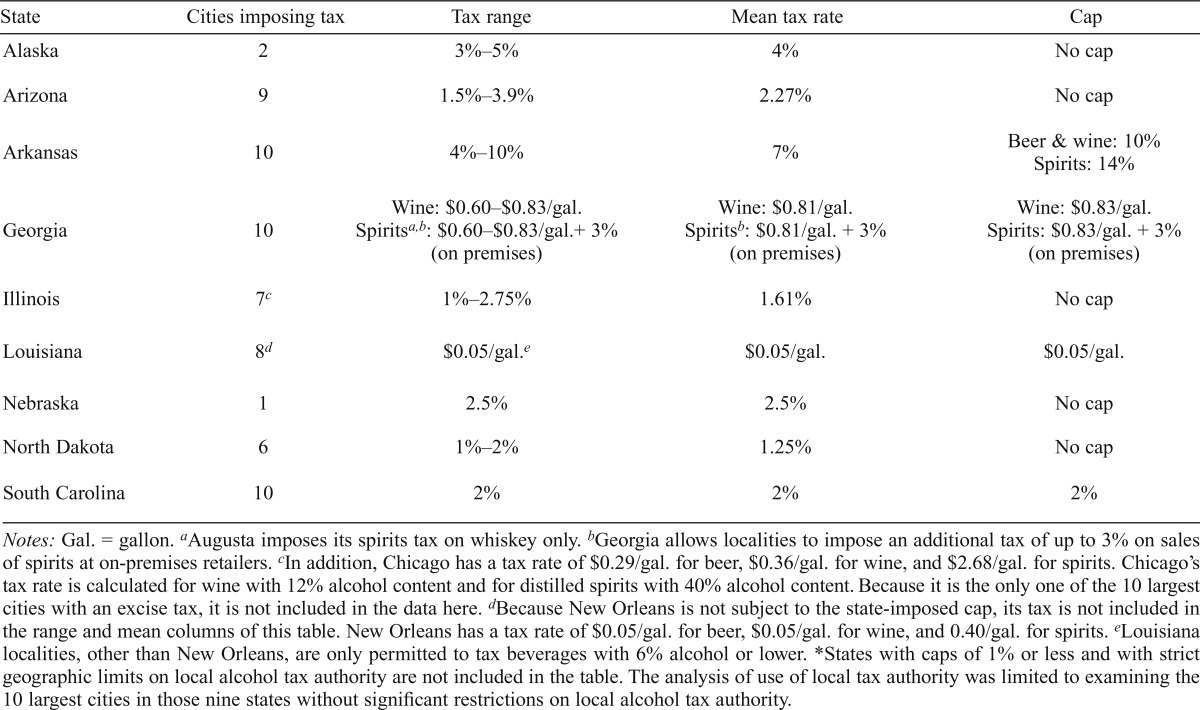

The use of local tax authority varies both across the nine states without caps or jurisdictional restrictions and among the 10 largest cities in those states (Table 2). For example, in Arkansas, Georgia, and South Carolina, all 10 of the largest cities impose local taxes, as do 9 of the 10 largest cities in Arizona and 8 of the 10 largest cities in Louisiana. By contrast, only 2 of the 10 largest cities in Alaska and 1 of the 10 largest cities in Nebraska have local alcohol taxes.

Table 2.

Use of local alcohol taxing authority by states that permit local taxation, January 2015*

| State | Cities imposing tax | Tax range | Mean tax rate | Cap |

| Alaska | 2 | 3%-5% | 4% | No cap |

| Arizona | 9 | 1.5%-3.9% | 2.27% | No cap |

| Arkansas | 10 | 4%-10% | 7% | Beer & wine: 10% Spirits: 14% |

| Georgia | 10 | Wine: $0.60-$0.83/gal. Spiritsaa,b: $0.60-$0.83/gal.+ 3% (on premises) | Wine: $0.81/gal. Spiritsa,b: $0.81/gal. + 3% (on premises) | Wine: $0.83/gal. Spirits: $0.83/gal. + 3% (on premises) |

| Illinois | 7c | 1%-2.75% | 1.61% | No cap |

| Louisiana | 8d | $0.05/gal.e | $0.05/gal. | $0.05/gal. |

| Nebraska | 1 | 2.5% | 2.5% | No cap |

| North Dakota | 6 | 1%-2% | 1.25% | No cap |

| South Carolina | 10 | 2% | 2% | 2% |

Notes: Gal. = gallon.

Augusta imposes its spirits tax on whiskey only.

Georgia allows localities to impose an additional tax of up to 3% on sales of spirits at on-premises retailers.

In addition, Chicago has a tax rate of $0.29/gal. for beer, $0.36/gal. for wine, and $2.68/gal. for spirits. Chicago’s tax rate is calculated for wine with 12% alcohol content and for distilled spirits with 40% alcohol content. Because it is the only one of the 10 largest cities with an excise tax, it is not included in the data here.

Because New Orleans is not subject to the state-imposed cap, its tax is not included in the range and mean columns of this table. New Orleans has a tax rate of $0.05/gal. for beer, $0.05/gal. for wine, and 0.40/gal. for spirits.

Louisiana localities, other than New Orleans, are only permitted to tax beverages with 6% alcohol or lower.

States with caps of 1% or less and with strict geographic limits on local alcohol tax authority are not included in the table. The analysis of use of local tax authority was limited to examining the 10 largest cities in those nine states without significant restrictions on local alcohol tax authority.

Among the five states that restrict which local jurisdictions are permitted to enact local taxes, New Mexico (McKinley County), New York (New York City), and Pennsylvania (Philadelphia and Allegheny County) limit local taxing authority to one or two specific local jurisdictions and place caps on the amount of tax permitted. In all three cases, the local government enacted alcohol taxes at the limit permitted (McKinley County: 6% ad valorem tax; New York City: $1 per gallon on distilled spirits; Philadelphia and Allegheny County: 10% ad valorem tax). For these three states, there can be no further local alcohol tax activity until the state either expands the number of local jurisdictions permitted to impose a tax or increases the cap. New Jersey limits local taxing authority to “class four” resort cities bordering the Atlantic Ocean, and Idaho permits local alcohol taxes only for resort cities with populations of 10,000 or fewer residents. We were unable to determine the cities that fit into these classifications and were therefore unable to assess the implementation of local alcohol taxes for these two states.

In general, cities in states that cap local alcohol taxes are more likely to impose such taxes than cities located in states with no caps, and are also likely to impose them at the maximum allowable rate. For example, all 10 cities in South Carolina, 9 of 10 in Georgia, and 7 of 10 in Louisiana have taxes at the cap level (excluding New Orleans, because it is not subject to the cap). Arkansas cities are an exception: the state has a cap of 14% for distilled spirits, and none of the 10 largest cities has a tax at that cap. Rather, they impose taxes that range from 4% to 10%, with a mean tax rate of 7%.

In contrast, the taxes imposed by cities in states without caps are relatively low. For example, only one city in Nebraska (Omaha) and two cities in Alaska (Fairbanks and Juneau) impose modest alcohol taxes, even though all cities in both states have local tax authority with no cap. Seven cities in Illinois impose ad valorem taxes on alcohol. However, all of these taxes are relatively low (mean tax rate = 1.61%), even though there is no cap on local alcohol taxes. In contrast, Chicago imposes an alcohol excise tax of $2.68 per gallon on distilled spirits, with lower excise taxes on beer and wine. Similarly, of the nine cities in Arizona and seven cities in North Dakota that impose local ad valorem taxes, the mean tax rates are only 2.27% and 1.25%, respectively, despite the absence of a cap in these states.

Discussion

This study adds a new dimension to the analysis of state alcohol taxes by characterizing the ability of localities to tax in different states. In some states, local taxes may affect many residents and may constitute a significant amount of additional tax. The existing body of alcohol tax research, which examines only state-level taxes, does not capture the effects of local taxes (Elder et al., 2010). This analysis shows that there are additional taxes being levied in states and, when used in conjunction with state-level research, can help provide more accurate tax rate estimates for particular localities. It also invites further research to explore the effects of local taxation.

To our knowledge, this is the first legal research study to examine local alcohol taxing authority. The results indicate that almost two in five states grant local governments some authority to tax alcoholic beverages. However, most of these states place some restrictions on this authority, including caps on local alcohol taxes, restrictions on the type of retailers where taxes can be imposed, and restrictions on the jurisdictions within the state that can levy taxes.

Our findings are subject to certain limitations. First, this analysis is restricted in scope to taxes and excludes fees. Second, this analysis does not address potential limitations on local authority arising from the often-complex rules regarding the authority of and interaction between local jurisdictions, which may affect the taxing of alcoholic beverages. For example, counties may or may not have authority to tax residents in cities within their boundaries, or the taxing authority may be limited to certain types of local jurisdictions (e.g., charter cities), or local taxes may require voter approval. Finally, the review of taxes enacted by localities was restricted to the 10 largest cities in a state, excluding smaller cities and all counties from the analysis.

The potential public health impact of state restrictions on local tax authority varies by the type of restriction and by the severity of the restrictions within each type. For example, five states restrict local alcohol taxes to 1% or less of the retail price, greatly reducing the potential public health impact of these taxes on excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Similarly, five states restrict the number of local jurisdictions that have local tax authority, which further reduces the potential public health impact of local alcohol taxes in those states.

State restrictions on the type of alcoholic beverages and type of sales that can be taxed by local governments can create other barriers to effective local alcohol tax policies. For example, any alcohol tax increase that is not consistently applied across all types of retail sales and beverages may encourage beverage switching and raise issues of equitable treatment of similar business entities. This may reduce the potential public health impact of local alcohol taxes and may make it more difficult to implement these taxes in the first place.

In contrast, earmarking restrictions may have little or no impact on potential public health outcomes because they are unlikely to change the effect local taxes have on the price of alcoholic beverages. In fact, earmarking requirements may have public health benefits. For example, New Mexico requires localities to use local alcohol tax revenues to support public health programs. However, some earmarking requirements may limit local tax levels if the funded activity is relatively inexpensive.

State restrictions on local alcohol tax authority can also be cumulative, making it important to examine the overall effect of state restrictions on local alcohol tax authority when more than one restriction exists. The absence of one type of restriction in state law may be offset by the presence of restrictions of another type. For example, Pennsylvania has a relatively high cap (10%) but grants local tax authority to only two jurisdictions (Philadelphia and Allegheny County).

Thus, looking at the cap alone would not give a complete picture of Pennsylvania’s local tax authority.

Unlike other forms of regulation, local alcohol taxation is not overly complex or burdensome for business because the taxes usually are passed on from retailers to consumers as higher retail prices for alcoholic beverages. Furthermore, local alcohol taxes allow local governments to recoup some of the costs of excessive alcohol consumption, including lost productivity, law enforcement, and health care expenditures. Arguments against local alcohol taxes focus on increased costs, including costs to government (administration), retailers (compliance), and consumers (higher prices). Specifically, the cost to consumers may be perceived as a threat to the service industry, as business may go to nearby localities.

State and local health departments can play an important role in discussions about increasing alcohol taxes and about other Community Guide (n.d.) recommendations for reducing excessive alcohol use. Public health agencies can assess the local public health impact of excessive alcohol use and related harms, the economic cost of excessive drinking, and local alcohol tax authority. This is particularly true in states where local tax authority is currently underused (e.g., Alaska, Arizona, Illinois, and North Dakota, where no major restrictions are imposed). In states with limited or no local alcohol tax authority, state and local public health agencies can work with partners to assess the potential public health benefits of expanding this authority, which could support other efforts to reduce excessive alcohol consumption and related harms.

In summary, there is strong scientific evidence that increasing the price of alcohol by raising taxes can reduce excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Local alcohol tax increases can complement state alcohol taxes, helping to reduce excessive drinking, while also providing funds that can be used to support prevention and treatment services at the local level. State legislation expanding local alcohol tax authority can also complement other effective community-based strategies (e.g., the regulation of alcohol outlet density) for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms.

References

- Community Guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; n.d. Excessive alcohol consumption. Retrieved from https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/excessive-alcohol-consumption. [Google Scholar]

- Diller P. A. Intrastate preemption. Boston University Law Review. 2007;87:1113–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Elder R. W., Lawrence B., Ferguson A., Naimi T. S., Brewer R. D, Chattopadhyay S. K., Fielding J. E. the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorovitz E., Mosher J., Pertschuk M. Preemption or prevention?: Lessons from efforts to control firearms, alcohol, and tobacco. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1998;19:36–50. doi:10.2307/3343088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr W. C., Patterson D., Greenfield T. K., Jones A. S., McGeary K. A., Terza J. V., Ruhm C. J. U.S. alcohol affordability and real tax rates, 19502011. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44:459–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.007. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher J. F., Treffers R. D. State pre-emption, local control, and alcohol retail outlet density regulation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.029. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi T. S. The cost of alcohol and its corresponding taxes in the U.S.: A massive public subsidy of excessive drinking and alcohol industries. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41:546–547. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.001. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol beverages taxes: Beer [beer taxes, policy description] n.d Retrieved from http://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/Taxes_Beer.html.

- Sacks J. J., Gonzales K. R., Bouchery E. E., Tomedi L. E., Brewer R. D. 2010 National and State costs of excessive alcohol consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49:e73–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Increasing alcoholic beverage taxes is recommended to reduce excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:230–232. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.002. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Const. amend. X [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Const. amend. XXI [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar A. C., Tobler A. L., Komro K. A. Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:2270–2278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.186007. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.186007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan Z., Chaloupka F. J., Blanchette J. G., Nguyen T. H., Heeren T. C., Nelson T. F., Naimi T. S. The relationship between alcohol taxes and binge drinking: Evaluating new tax measures incorporating multiple tax and beverage types. Addiction. 2015;110:441–450. doi: 10.1111/add.12818. doi:10.1111/add.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]