Abstract

Objective:

Overservice of alcohol (i.e., selling alcohol to intoxicated patrons) continues to be a problem at bars and restaurants, contributing to serious consequences such as traffic crashes and violence. We developed a training program for managers of bars and restaurants, eARMTM, focusing on preventing overservice of alcohol. The program included online and face-to-face components to help create and implement establishment-specific policies.

Method:

We conducted a large, randomized controlled trial in bars and restaurants in one metropolitan area in the midwestern United States to evaluate effects of the eARM program on the likelihood of selling alcohol to obviously intoxicated patrons. Our outcome measure was pseudo-intoxicated purchase attempts—buyers acted out signs of intoxication while attempting to purchase alcohol—conducted at baseline and then at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months after training. We conducted intention-to-treat analyses on changes in purchase attempts in intervention (n = 171) versus control (n = 163) bars/restaurants using a Time × Condition interaction, as well as planned contrasts between baseline and follow-up purchase attempts.

Results:

The overall Time × Condition interaction was not statistically significant. At 1 month after training, we observed a 6% relative reduction in likelihood of selling to obviously intoxicated patrons in intervention versus control bars/restaurants. At 3 months after training, this difference widened to a 12% relative reduction; however, at 6 months this difference dissipated. None of these specific contrasts were statistically significant (p = .05).

Conclusions:

The observed effects of this enhanced training program are consistent with prior research showing modest initial effects followed by a decay within 6 months of the core training. Unless better training methods are identified, training programs are inadequate as the sole approach to reduce overservice of alcohol.

Alcohol consumption has been linked to traffic crashes (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [NHTSA], 2015) and violence (Branas et al., 2016; Felson & Staff, 2010; McClelland & Teplin, 2001). Businesses licensed to sell alcohol influence alcohol use and the incidence of these problems. Specifically, overconsumption of alcohol at on-premise consumption locations (i.e., bars, restaurants) has been directly linked to aggressive events within establishments (Graham & Wells, 2001; Graham et al., 2006; Quigley & Leonard, 2004) and drinking and driving upon leaving the establishments (Naimi et al., 2009).

Alcohol establishments in the United States and other countries have a high likelihood of selling alcohol to obviously intoxicated patrons despite laws prohibiting these sales (Andréasson et al., 2000; Buvik, 2013; Buvik & Rossow, 2015; Clapp et al., 2009; Freisthler et al., 2003; Gosselt et al., 2013; Hughes et al., 2014; Lenk et al., 2006; Toomey et al., 1999, 2004, 2016). Many of these studies have assessed likelihood of sales to obviously intoxicated persons through purchase attempts by pseudo-intoxicated patrons (i.e., actors acting out signs of obvious intoxication when attempting to purchase alcohol) and found that the pseudo-intoxicated patrons are able to purchase alcohol in 58%–95% of their attempts.

A common way to address overservice of alcohol is through responsible beverage service training programs. Several studies have concluded that support of management is essential for creating environments to sustain and increase responsible beverage service among servers (Howard-Pitney et al., 1991; McKnight, 1991; NHTSA, 1986). Managers, not servers, determine promotional policies and establish expectations about responsible alcohol service within an establishment (McKnight, 1993; Saltz, 1989).

In the late 1990s, the Alcohol Epidemiology Program (AEP) at the University of Minnesota developed a management-specific training program called the Alcohol Risk Management (ARMTM) program (Toomey et al., 2001). The ARM program provided onsite, skill-building training for general managers to promote adoption of responsible serving policies. Trainers assisted managers in creating an establishment-specific policy manual and then helped the manager introduce the new policies at a staff meeting.

In a randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate the ARM program, 90% of the contacted establishments agreed to participate in the study, and 85% completed all four face-to-face sessions. Intervention establishments adopted, on average, 13 of the 18 recommended policies that focused on preventing overservice of alcohol and promoting safe environments. The research team observed a 23% decrease in likelihood of illegal alcohol sales to obviously intoxicated patrons in the intervention sites (n = 122) compared with the control sites (n = 109) within 1 month following the training sessions (p = .06). However, effects of the training decayed within 3 months (Toomey et al., 2008). We hypothesized that the ARM program was limited by (a) no contact with intervention bars and restaurants following completion of the training sessions, thus decreasing the salience of the program messages over time; (b) lack of training to help managers systematically implement and enforce the new policies; and (c) no tools for training staff on responsible beverage service beyond the staff meeting.

AEP created a new version of the ARM program called the Enhanced Alcohol Risk Management (eARMTM) program designed to sustain effects of the original program. The eARM program includes both in-person and online components. In this article, we present the results of (a) the intention-to-treat analyses conducted to assess short- and long-term effects of the eARM program on likelihood of sales to obviously intoxicated patrons and (b) post hoc analyses to identify potential moderators of program effects.

Method

We conducted a trial in a large metropolitan area in the midwestern United States to evaluate effects of the eARM program. Our main outcome measure was pseudo-intoxicated purchase attempts. This project was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Study design

We used a randomized controlled study design, with participating bars and restaurants randomly assigned to a full intervention (eARM) or to a delayed, brief intervention (eARM Express), which served as the control group. eARM Express was offered to a control establishment after all data collection had been completed for that establishment. We recruited the main decision maker (i.e., manager) at each establishment and gave them $100 to participate in the study. We conducted pseudo-intoxicated purchase attempts at baseline and then 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months after completion of the eARM program.

We recruited establishments to participate in the study between October 2011 and December 2013. Recruitment was staggered across communities to increase study feasibility for intervention and evaluation activities. Staff sent out postcards describing the eARM program to an establishment within 2 weeks of the first recruitment telephone call. Local licensing or law enforcement leaders in most of the communities sent a letter to their on-premise establishments to make them aware of the study. eARM program staff recruited managers by telephone. Once managers agreed to participate, we randomly assigned establishments to either the intervention or the control condition.

To help control for differences in timing of purchase attempts across conditions, we linked intervention and control establishments. The timing of data collection (e.g., follow-up purchase attempts) in control establishments mirrored timing of data collection with the linked intervention establishment. Establishments were linked after they had been randomly assigned to condition; an establishment was linked with the next establishment that was randomly assigned to the opposite condition within the same geographical area.

Communities

Our sample of alcohol establishments was located in 15 communities that had a minimum of 20 on-premise alcohol establishments accessible to the public and reasonable driving distance. Communities ranged in population size from 19,540 to 382,578 and had 20–334 on-premise establishments.

Establishments

We obtained a list of 1,132 on-premise establishments for the 15 communities from the state alcoholic beverage control agency. Among these establishments, 128 had gone out of business, 10 were excluded for safety reasons, 20 were excluded because management was already participating in the eARM program with another establishment (i.e., restaurants with multiple locations), and 127 were excluded for other reasons (lack of computer or internet access, language barrier, strip club, theater, private club, museum, irregular hours, seasonal, low-alcohol beer license only, and no longer having a liquor license). Of the 847 remaining establishments where we attempted to contact a manager, 40% (n = 342) agreed to participate in the study and were randomly assigned to condition. Two establishments were subsequently excluded because of language challenges. Among the remaining establishments, 175 were assigned to the eARM condition, and 165 were assigned to the control condition. Six establishments did not provide written consent to participate and were removed from the study. Our final number of establishments included in the study was 334 (171 intervention, 163 control).

Interventions

Following is a description of the full eARM and delayed eARM Express programs.

eARM program.

The goal of the eARM program was to promote the adoption and implementation of written establishment policies to encourage responsible alcohol service. The eARM program consisted of two face-to-face sessions as well as online components. The intervention was based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), focusing on the manager’s behavioral, personal, and environmental factors that support policy development and implementation. The intervention consisted of a core training phase followed by a maintenance phase.

The first face-to-face session was conducted at the establishment within about 2 weeks of recruitment. During this session, the trainer and the manager discussed the history of and rationale for the eARM program and how to log into and navigate the eARM website. Following completion of this session, managers had the information necessary to complete their establishment policy manual through the interactive website, which was hosted on a secure university server.

The eARM website’s home page included a Task List with a suggested due date and an assigned point value for each task (e.g., building the policy manual). Managers accrued points for tasks completed, making them eligible for quarterly prize drawings. To build their policy manual, managers were asked to complete six e-learning modules: (a) How to Build a Policy Manual, (b) Prevent Sales to Underage Persons, (c) Prevent Sales to Intoxicated Patrons, (d) Slow Alcohol Consumption, (e) Improve Management and Security, and (f) Business Considerations. Managers were also given (a) information about why policies are important; (b) tips on adopting, implementing, and enforcing policies; (c) a policy definition and rationale for each of 14 recommended policies; and (d) recommendations for what managers and servers should do to comply with the policy. Managers could choose to accept a policy, customize the policy, or reject it.

Managers then submitted the policy manual to their trainer. Trainers encouraged managers to work with other managers, owners, human resource staff, and/or attorneys before submitting their policy manual as complete for the trainer to review. Trainers contacted participants to discuss policy customizations and to ensure that participants had accepted all of the policies relevant for their establishment. On average, the managers adopted 12 of the recommended 14 policies. Of those policies that were adopted, 11% were customized (i.e., modified from the original recommended policy). Three members of the research team reviewed each modification independently and coded it as (a) same as recommended, (b) weaker, or (c) stronger. Discrepancies were then discussed until consensus was reached about the appropriate code for each modification. Of the 11% of policies that were modified, 7% were modified to be weaker and 4% were modified to be stronger.

Once managers finalized the policy manual, the second face-to-face session was conducted. This was a 1-hour staff meeting with management and service staff to discuss the new establishment policies and to provide an overview of state laws and potential liability related to alcohol service. The trainer encouraged managers to pay staff for attending the staff meeting and provided snacks and small prizes to promote engagement during the meeting. Completion of the staff meeting marked the ending of the core training phase of the eARM program and the beginning of the maintenance phase. Throughout both phases—and after data collection had ended—managers could access the online Resource Center. The Resource Center provided easy access to all of the recommended policies and related tools, training videos, and resources to support policy implementation.

During the 6-month maintenance phase, managers were reminded by trainers via email and telephone to use the resources on the website. Trainers also provided managers with information about new alcohol laws and notified them of new tools that were added to the Resource Center. Trainers also encouraged the managers to use the online staff training tool available through the eARM website. Managers could continue to accrue points for the prize drawings by using the website.

The online server training component was embedded within the eARM website. This training provided basic information about laws pertaining to alcohol service and instructions and short videos regarding responsible alcohol service. The server training also included descriptions of the policies (including customizations) that their manager selected for their establishment.

eARM Express.

After follow-up data collection for a control establishment, the trainer provided log-in information for the eARM Express website. The eARM Express website included information about all of the recommended policies and the full Resource Center, but it was not customizable.

Purchase attempts/observations

We conducted purchase attempts at baseline and each follow-up time point, using the same protocol used in the evaluation of the ARM program (Toomey et al., 2008). We hired actors to serve as buyers (i.e., to act out signs of obvious intoxication while attempting to purchase alcohol). Actors were trained to follow a standardized protocol that has been used in thousands of purchase attempts as part of previous studies (Lenk et al., 2006; Toomey et al., 1999, 2004). All buyers were accompanied by an observer for safety. A full description of the protocol can be found in Toomey et al. (2016). Buyers and observers recorded observations of the servers, establishments, and purchase attempts. Visits to all establishments were made between 5:00 p.m. and 11:00 p.m. on Friday and Saturday evenings.

Measures

The dependent variable was whether the buyer was able to purchase alcohol from the establishment (yes, no). The primary independent variable was intervention assignment (1 = intervention condition, 0 = control condition). To complete exploratory analyses, we created four dichotomous variables to assess the effects of level of participation among establishments assigned to the intervention condition: (a) completed core training, (b) completed successful staff meeting, (c) high engagement from manager, and (d) demonstrated at least moderate use of the website after the core training. A successful staff meeting was based on a sum of three dichotomous (yes =1, no = 0) measures of whether (a) a point-of-contact manager was present, (b) a manager helped present information, and (c) other managers were present (total score ≥ 2 is considered a successful staff meeting). Managers’ engagement throughout the training was also rated by the trainers and based on sum of three ratings (1–4 Likert scales) of the manager’s (a) interest, (b) engagement, and (c) responsiveness to communication (score ≥ 10 is considered high engagement). Moderate use of the website after the core training was defined as logging in 8 or more times, downloading at least one resource, and/or having at least one server participate in online server training (measure defined based on frequency distribution of these tasks across managers). Finally, we analyzed three establishment characteristics that might moderate intervention effects: (a) type of liquor license (full liquor license vs. wine/beer license), (b) type of ownership (corporate vs. independent), and (c) type of establishment (restaurant vs. bar or bar/restaurant). Type of license was obtained from license lists, type of ownership was determined via establishment websites and/or discussion with managers, and type of establishment was determined during purchase attempts.

Analyses

We conducted descriptive statistics for all measures. We then compared establishments in each condition at baseline on numerous characteristics, including our dependent variable and other variables that defined characteristics of the neighborhoods (e.g., residential vs. commercial; city vs. suburb), establishments (e.g., number of servers, staff turnover rate), and managers (e.g., years in the service industry) that we collected as part of purchase attempts, licensing lists, or surveys with managers (see Toomey et al., 2016, and Nederhoff et al., 2016, for more complete description of these variables). We did not find any statistically significant differences between the conditions, suggesting that the randomization was successful; as a result, none of these variables was included in our outcome analyses.

We estimated a series of mixed-effect logistic regressions using an intention-to-treat approach to analyze changes in our dependent variable (pseudo-intoxicated sales rates) over time in intervention versus control establishments. We included buyer identification as a random effect to control for potential variation in sales rates to our individual buyers. We tested our primary hypothesis using the Time × Condition interaction, a three-degrees-of-freedom test. We further explored this overall test with single degree of freedom planned contrasts, looking at effects from baseline to the first follow-up purchase attempt, from baseline to the second follow-up purchase attempt, and from baseline to the third follow-up purchase attempt.

Finally, we conducted a series of post hoc analyses to assess the effects of differing levels of participation and potential moderating effects of establishment characteristics. We did not design the study or have the power to conduct these analyses. We conducted these exploratory analyses to generate hypotheses for future studies. As with our main intention-to-treat analyses, for level of participation effects, we tested Time × Condition interactions followed by planned contrasts for each time point. For moderating effects, we tested three-way interaction terms between the potential moderator and Time × Condition, also followed by planned contrasts at each time point.

Results

Intention-to-treat analyses

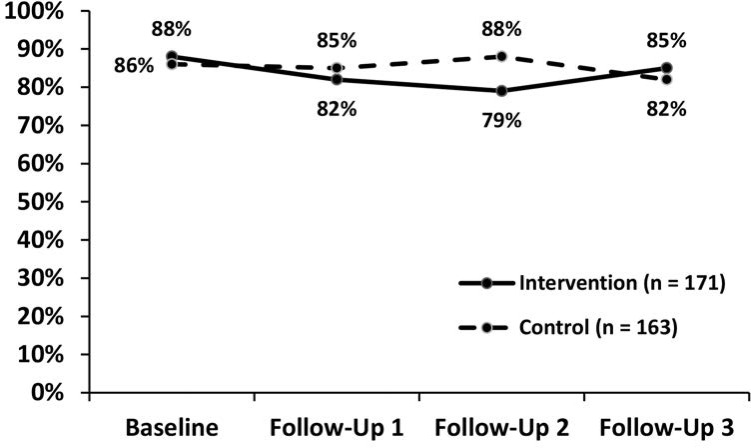

Figure 1 shows results of the purchase attempts for each condition across baseline and the three follow-up time points. The overall Time × Condition interaction was not statistically significant (Table 1). We also assessed the effects at each of the follow-up periods compared with baseline. At baseline, the alcohol sales rates were very similar (intervention = 88%; control = 86%). At 1 month after core training, the sales rates began to separate, with intervention establishments having a 6% relative reduction in likelihood of selling to obviously intoxicated patrons compared with control establishments. At 3 months after core training, the sales rates between the two groups widened, with intervention sites having a 12% relative reduction in selling alcohol to our pseudo-intoxicated buyers compared with the control sites. However, at 6 months after core training, the sales rates were reversed, with intervention establishments slightly more likely than control establishments to sell alcohol to our buyers. None of these specific contrasts was statistically significant at the p = .05 level.

Figure 1.

Intention to treat: Least square means of purchase rates at each time point

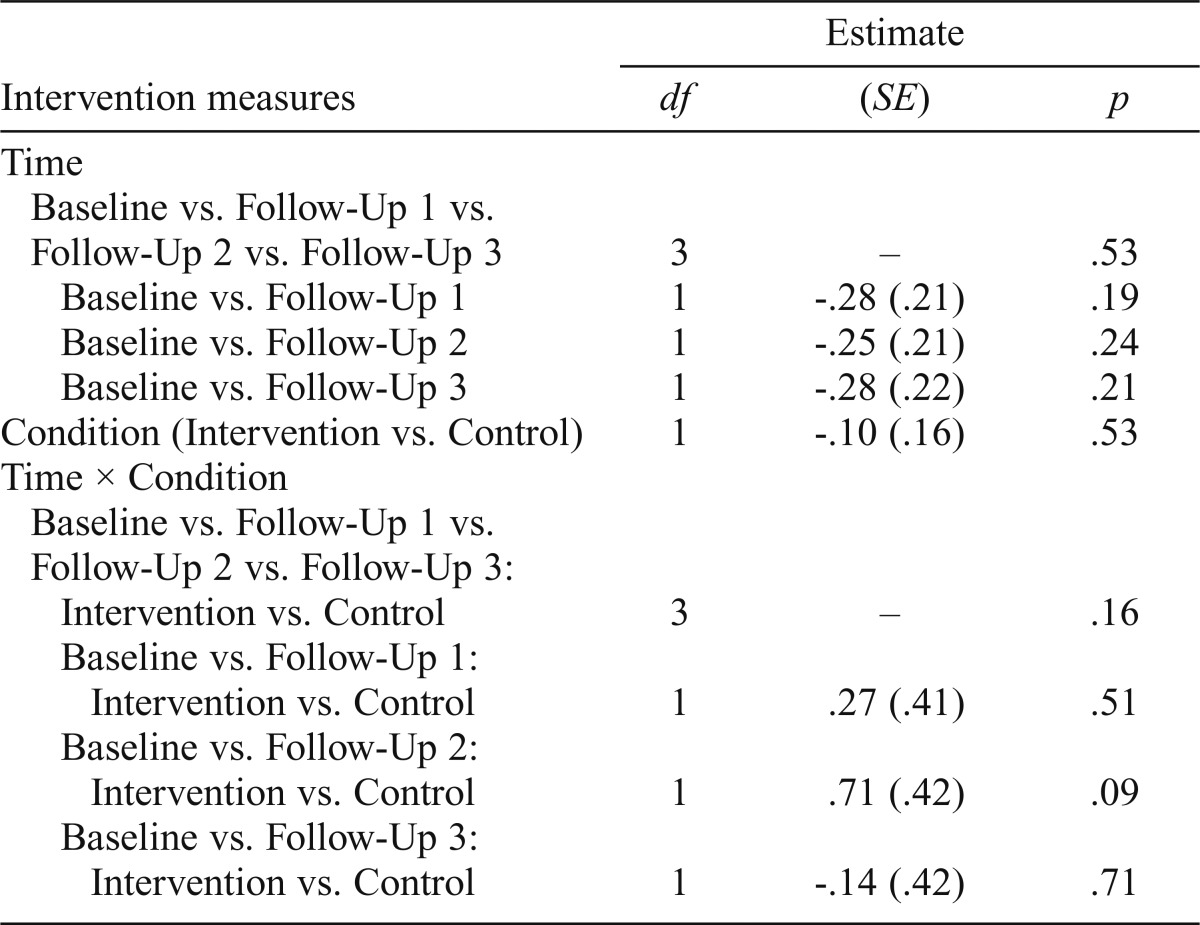

Table 1.

Intention to treat results: unadjusted models

| Intervention measures | Estimate |

||

| df | (SE) | p | |

| Time | |||

| Baseline vs. Follow-Up 1 vs. Follow-Up 2 vs. Follow-Up 3 | 3 | – | .53 |

| Baseline vs. Follow-Up 1 | 1 | -.28 (.21) | .19 |

| Baseline vs. Follow-Up 2 | 1 | -.25 (.21) | .24 |

| Baseline vs. Follow-Up 3 | 1 | -.28 (.22) | .21 |

| Condition (Intervention vs. Control) | 1 | -.10 (.16) | .53 |

| Time × Condition | |||

| Baseline vs. Follow-Up 1 vs. Follow-Up 2 vs. Follow-Up 3: Intervention vs. Control | 3 | – | .16 |

| Baseline vs. Follow-Up 1: Intervention vs. Control | 1 | .27 (.41) | .51 |

| Baseline vs. Follow-Up 2: Intervention vs. Control | 1 | .71 (.42) | .09 |

| Baseline vs. Follow-Up 3: Intervention vs. Control | 1 | -.14 (.42) | .71 |

Post hoc analyses

Levels of participation of intervention.

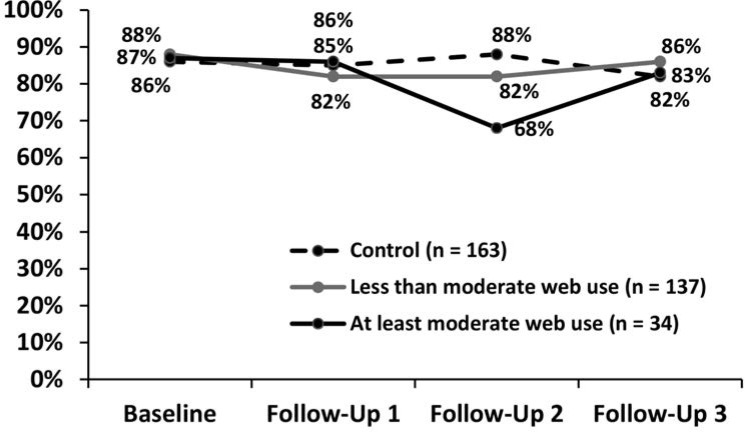

Among the 171 establishments assigned to the eARM condition where consent was obtained, 119 (70%) completed the core training. Among these establishments, our trainers indicated that 72 (61%) had a successful staff meeting. The trainers indicated that 79 (46%) of the participating managers were very engaged with the training program. Thirty-four establishments (20%) demonstrated at least moderate use of the eARM website after the core training. We did not observe statistically significant differences (at p = .05 level) in sales rates to our pseudo-intoxicated buyers for any of the participation variables. However, although not statistically significant, we did observe a much lower sale rates at the second follow-up at intervention establishments that demonstrated at least moderate use of the website (after the core training) compared with control establishments (Figure 2). The 34 establishments that used the website to at least a moderate extent had a 68% sales rate compared with 87% among controls (p = .08).

Figure 2.

Website use after core training: Least square means of purchase rates at each time point

Potential moderators.

Among intervention establishments, 69% had full liquor licenses, 26% were bars, and 18% were corporately owned. Among control establishments, 72% had full liquor licenses, 32% were bars, and 16% were corporately owned. We found no statistically significant moderating effects for these three establishment characteristics. Among intervention establishments, we observed lower sales rates for full liquor licenses (vs. wine/beer licenses), bars (vs. restaurants or bar/restaurants), and corporate establishments (vs. independent establishments) at 1 month and/or 3 months after core training. Some of the largest differences in purchase rates were observed (a) at first follow-up for bars (69%) versus restaurants or bars/restaurants (86%), and (b) at second follow-up for corporate (73%) versus independent (81%) establishments. At 6 months after training, intervention establishments in all of these categories had similar or lower purchase rates than corresponding control establishments.

Discussion

The goal of the eARM program was to obtain and sustain training effects on the likelihood of sales to intoxicated patrons. However, we did not observe statistically significant differences in the likelihood of sales rates in intervention and comparison sites. At 1 month after core training, we observed a nonsignificant difference in sales of 6%. At 3 months after training, we observed a 12% relative reduction in likelihood of selling, although this failed to reach statistical significance. The original ARM training program appeared to reduce the likelihood of sales to obviously intoxicated patrons 1 month after training (a 23% relative reduction between intervention and control), but effects of the training decayed by 3 months after training (Toomey et al., 2008).

In the original ARM program, our trainers met four times, face-to-face with the managers from one city within a short timeframe. They built strong relationships with the managers and walked them through all stages of policy adoption. With the eARM program, the trainers met briefly during the first session and again at the staff meeting, with managers completing the online training on their own. We devoted significant resources to develop the website in hopes that the mangers could work independently through the training. However, our trainers spent a considerable amount of time encouraging and helping managers to complete the online training components. Although online training programs are convenient, not all managers may have the interest or sufficient motivation to complete them. Thirty percent of the establishments did not complete the core eARM training, whereas only 15% of the establishments did not complete the ARM training.

Most managers indicated that they liked the trainer and program materials, but some thought the online training was time consuming; this could explain why such a large percentage did not complete the core training. In the ARM training, trainers helped managers select establishment policies and then constructed the policy manual for them. This may have required less of the managers’ time and provided external motivation to complete the program. Sustained participation in online health interventions is challenging, and studies suggest that levels of engagement vary by participant characteristics and attitudes (Glasgow et al., 2007) as well as the breadth and depth of intervention tailoring (Wanner et al., 2010). Research is needed to determine the best way to encourage ongoing participation in online alcohol management training programs. Alternatively, we need to explore ways to sustain effects of face-to-face programs like the ARM program, such as through ongoing booster sessions.

The ARM training program appeared to have an immediate effect (at 1 month) on propensity to sell to intoxicated patrons. In contrast, the largest potential effect for the eARM program appeared to occur at 3 months. The reason for this apparent difference is not clear. Both training programs promoted and helped general managers adopt establishment-level policies and introduced the policies at a staff meeting. The eARM program provided implementation tips, including having more systems in place to actively monitor and enforce the establishment policies and to ensure that all managers were backing up serving staff. It is possible that the effect appeared delayed for eARM as general managers put procedures into place to fully implement and enforce the policies.

In an attempt to extend the effects of the training that we observed with the original ARM program, we developed a variety of tools that were available on the eARM website. We also incentivized and encouraged use of the website after the core training was completed. The 34 establishments that continued at least a moderate use of the website after the core training appeared to be less likely to sell alcohol to our buyers than other establishments. It is possible that the resources on the website were helpful to establishments in implementing their policies. It is also possible that continued engagement of the managers with the eARM training materials reminded them to continue focusing attention on preventing overservice in their establishments. Of course, it is also possible that the managers who used the website more were more concerned about overservice from the onset of the program. Future research should assess strategies for encouraging managers to continue using a website and resources similar to eARM and to fully assess whether this continued use is associated with less overservice of alcohol.

eARM was designed to be flexible enough to be adapted to a wide range of licensed establishments, but it is possible that the program was a better fit for some types of establishments than others. We conducted post hoc analyses to assess whether the eARM program had different effects on the purchase rate by type of establishment. Although our study was not powered to fully assess these moderating effects, it appears possible that the eARM training program was more promising for bars (vs. restaurants) and corporate (vs. independent) establishments. More research is needed to determine whether these potential moderating effects are real, and if so, why.

One limitation of the current study is that it was conducted in one metropolitan area; effects of training programs such as eARM should be evaluated in other locations. In addition, our participation rate in this study was lower than in our previous ARM trial (40% vs. 90%); however, our current participation rate was similar to that of other studies (Saltz & Stanghetta, 1997; Toomey et al., 2001; Wagenaar et al., 2005). Establishments that choose to participate in this type of study may be different from those that refused to participate. However, in an earlier study, we found no difference in likelihood of illegal alcohol sales between those establishments that agreed to participate and those that did not (Fabian et al., 2005). Furthermore, given the high likelihood of alcohol sales to obviously intoxicated patrons, it is important to start with establishments that are motivated to participate in these types of training programs to help them shift their serving practices and then put pressure on the other establishments in their communities to also change their serving practices.

Over the past few decades, the likelihood of sales to obviously intoxicated patrons in the United States and other countries has remained high (Buvik, 2013; Buvik & Rossow, 2015; Clapp et al., 2009; Gosselt et al., 2013; Hughes et al., 2014; Toomey et al., 2016). Training programs are a frequently used approach to address overservice of alcohol, and programs such as the eARM program can provide information that is needed to help establishments comply with the law. However, unless we can identify methods for sustaining their effects, we cannot rely on these training programs as our only approach to reduce overservice of alcohol.

We also need to identify other strategies, such as enforcement efforts, to target this problem. It is possible that some combination of training and enforcement may ultimately be needed to reduce overservice of alcohol. For example, a community-wide intervention could be conducted where eARM training is offered to establishments that are also told that law enforcement would be conducting an enforcement campaign focusing on overservice of alcohol. Following the enforcement campaign, the core training could be offered to other establishments and booster sessions to the initial participants. The participants may be more motivated to take part in and fully implement the eARM policies in the context of potential penalties for overservice policies. However, research is needed to determine whether a combination of these approaches is more effective than either alone and what the ideal combination should be.

References

- Andréasson S., Lindewald B., Rehnman C. Over-serving patrons in licensed premises in Stockholm. Addiction. 2000;95:359–363. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9533596.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9533596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Englewood Cliffs, NH: Prentice Hall; 1986. Social foundations of thought and action. A social cognitive theory. [Google Scholar]

- Branas C. C., Han S., Wiebe D. J. Alcohol use and firearm violence. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2016;38:32–45. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buvik K. How bartenders relate to intoxicated customers. International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research. 2013;2:1–6. doi:10.7895/ijadr.v2i2.120. [Google Scholar]

- Buvik K., Rossow I. Factors associated with over-serving at drinking establishments. Addiction. 2015;110:602–609. doi: 10.1111/add.12843. doi:10.1111/add.12843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp J. D., Reed M. B., Min J. W., Shillington A. M., Croff J. M., Holmes M. R., Trim R. S. Blood alcohol concentrations among bar patrons: A multi-level study of drinking behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;102:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.015. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian L. E. A., Toomey T. L., Mitchell R. J., Erickson D. J., Vessey J. T., Wagenaar A. C. Do organizations that voluntarily participate in a program differ from non-participating organizations? Evaluation and Program Planning. 2005;28:161–165. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.07.008. [Google Scholar]

- Felson R. B., Staff J. The effects of alcohol intoxication on violent versus other offending. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2010;37:1343–1360. doi:10.1177/0093854810382003. [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B., Gruenewald P. J., Treno A. J., Lee J. Evaluating alcohol access and the alcohol environment in neighborhood areas. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:477–484. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057043.04199.B7. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000057043.04199.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Nelson C. C., Kearney K. A., Reid R., Ritzwoller D. P., Strecher V. J., Wildenhaus K. Reach, engagement, and retention in an Internet-based weight loss program in a multi-site randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2007;9(2):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e11. doi:10.2196/jmir.9.2.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselt J. F., Van Hoof J. J., Goverde M. M., De Jong M. D. T. One more beer? Serving alcohol to pseudo-intoxicated guests in bars. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1213–1219. doi: 10.1111/acer.12074. doi:10.1111/acer.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K., Osgood D. W., Wells S., Stockwell T. To what extent is intoxication associated with aggression in bars? A multilevel analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:382–390. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.382. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K., Wells S. Aggression among young adults in the social context of the bar. Addiction Research and Theory. 2001;9:193–219. doi:10.3109/16066350109141750. [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Pitney B., Johnson M. D., Altman D. G., Hopkins R., Hammond N. Responsible alcohol service: A study of server, manager, and environmental impact. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:197–199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.197. doi:10.2105/AJPH.81.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K., Bellis M. A., Leckenby N., Quigg Z., Hardcastle K., Sharples O., Llewellyn D. J. Does legislation to prevent alcohol sales to drunk individuals work? Measuring the propensity for night-time sales to drunks in a UK city. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2014;68:453–456. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203287. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-203287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenk K. M., Toomey T. L., Erickson D. J. Propensity of alcohol establishments to sell to obviously intoxicated patrons. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1194–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00142.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland G. M., Teplin L. A. Alcohol intoxication and violent crime: Implications for public health policy. American Journal on Addictions. 2001;10(Supplement SI):s70–s85. doi: 10.1080/10550490150504155. doi:10.1080/10550490150504155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight A. J. Factors influencing the effectiveness of server-intervention education. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:389–397. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.389. doi:10.15288/jsa.1991.52.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight J. A. Server intervention: Accomplishments and needs. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1993;17:76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Naimi T. S., Nelson D. E., Brewer R. D. Driving after binge drinking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.013. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Washington, DC: Author; 2015. Traffic safety facts: 2014 data. Alcohol-impaired driving (DOT HS 812 231) [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Washington, DC: Author; 1986. TEAM: Techniques of effective alcohol management: Findings from the first year. [Google Scholar]

- Nederhoff D. M., Lenk K. M., Horvath K. J., Nelson T. F., Ecklund A. M., Erickson D. J., Toomey T. L. Alcohol service policies and practices: A survey of bar and restaurant managers. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0047237917724408. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley B. M., Leonard K. E. Alcohol use and violence among young adults. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Saltz R. F. Research needs and opportunities in server intervention programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1989;16:429–438. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600310. doi:10.1177/109019818901600310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltz R. F., Stanghetta P. A community-wide Responsible Beverage Service program in three communities: Early findings. Addiction. 1997;92(Supplement 2):S237–S249. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb02994.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey T. L., Erickson D. J., Lenk K. M., Kilian G. R., Perry C. L., Wagenaar A. C. A randomized trial to evaluate a management training program to prevent illegal alcohol sales. Addiction. 2008;103:405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02077.x. discussion 414–415. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey T. L., Lenk K. M., Nederhoff D. M., Nelson T. F., Ecklund A. M., Horvath K. J., Erickson D. J. Can obviously intoxicated patrons still easily buy alcohol at on-premise establishments? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40:616–622. doi: 10.1111/acer.12985. doi:10.1111/acer.12985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey T. L., Wagenaar A. C., Erickson D. J., Fletcher L. A., Patrek W., Lenk K. M. Illegal alcohol sales to obviously intoxicated patrons at licensed establishments. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:769–774. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000125350.73156.ff. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000125350.73156.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey T. L., Wagenaar A. C., Gehan J. P., Kilian G., Murray D. M., Perry C. L. Project ARM: Alcohol risk management to prevent sales to underage and intoxicated patrons. Health Education & Behavior. 2001;28:186–199. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800205. doi:10.1177/109019810102800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey T. L., Wagenaar A. C., Kilian G., Fitch O., Rothstein C., Fletcher L. Alcohol sales to pseudo-intoxicated bar patrons. Public Health Reports. 1999;114:337–342. doi: 10.1093/phr/114.4.337. doi:10.1093/phr/114.4.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar A. C., Toomey T. L., Erickson D. J. Preventing youth access to alcohol: Outcomes from a multi-community time-series trial. Addiction. 2005;100:335–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00973.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner M., Martin-Diener E., Bauer G., Braun-Fahrländer C., Martin B. W. Comparison of trial participants and open access users of a web-based physical activity intervention regarding adherence, attrition, and repeated participation. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12(1):e3. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1361. doi:10.2196/jmir.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]