Abstract

Objective:

Research demonstrates alcohol temporally precedes and increases the odds of violence between intimate partners. However, despite an extensive theoretical literature on factors that likely moderate the relationship between alcohol and dating violence, minimal empirical research has examined such moderators.

Method:

The purpose of the present study was to examine two potential moderators of this association: trait anger and partner-specific anger management. Undergraduate men (N = 67) who had consumed alcohol within the past month and were in current dating relationships completed a baseline assessment of their trait anger and partner-specific anger management skills and subsequently completed daily assessments of their alcohol use and violence perpetration (psychological, physical, and sexual) for up to 90 consecutive days.

Results:

Alcohol was significantly associated with increased odds of physical aggression among men with relatively high but not low trait anger and partner-specific anger management deficits. In contrast, alcohol was significantly associated with increased odds of sexual aggression among men with relatively low trait anger and partner-specific anger management deficits.

Conclusions:

Our findings demonstrate important differences in the roles of acute intoxication and anger management in the risk of physical aggression and sexual dating violence. Interventions for dating violence may benefit from targeting both alcohol and adaptive anger management skills.

Research demonstrates that alcohol temporally precedes and increases the risk of dating violence among male college students (Moore et al., 2011; Shorey et al., 2014b). Shorey et al. (2014b), for example, used a 90-day diary to demonstrate increased odds of dating violence on any drinking and heavy drinking days (defined as 5 or more drinks on one occasion; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1995) in a sample of college men in a current dating relationship. Specifically, men were 1.78 times more likely to perpetrate psychological aggression on heavy drinking days; 2.04 and 3.93 times more likely to perpetrate physical aggression on any drinking and heavy drinking days, respectively; and 3.87 and 2.02 times more likely to perpetrate sexual aggression on any drinking and heavy drinking days, respectively. This is consistent with a large literature demonstrating that alcohol increases the risk of aggression generally (e.g., Giancola et al., 2009) and against intimate partners specifically (Foran & O’Leary, 2008). This has led some to conclude that alcohol is likely a contributing cause of aggression (Leonard, 2005).

Nevertheless, Giancola (2000) postulated that alcohol-related violence may only occur among individuals who are routinely low in their “threshold for aggression.” That is, individuals who have a low threshold for aggression (e.g., high trait anger, poor emotion regulation) may be particularly likely to perpetrate violence when under the acute effects of alcohol, as acute alcohol use impairs executive functioning and, thus, places individuals at risk for aggression. This is consistent with multiple threshold models of alcohol-related aggression, which suggest that alcohol interacts with other risk factors (e.g., trait anger) to predict aggression (Fals-Stewart et al., 2005)

In support of this idea, Giancola (2002) demonstrated that alcohol was more likely to lead to aggression, measured via a laboratory-based aggression paradigm, for participants high—relative to low—in trait anger. Other studies support various indicators of anger management and trait anger as moderators of the alcohol–aggression link in laboratory-based research that have used various indicators of aggressive behavior (e.g., Eckhardt & Crane, 2008; Giancola et al., 2012; Stappenbeck & Fromme, 2014).

Based on the research described above, two potential indicators for having a low threshold for dating violence are trait anger and partner-specific anger management deficits. Trait anger is defined as a broad predisposition to experience anger and/or respond to stressful and distressing situations with anger (Spielberger, 1988) and is a robust correlate of intimate partner violence (Finkel et al., 2012; Shorey et al., 2011; Taft et al., 2010). Partner-specific anger management is defined as cognitive and behavioral strategies (e.g., taking a “time-out”; relaxation strategies) used in an attempt to reduce anger directed toward a partner (Stith & Hamby, 2002); it has also been shown to predict more frequent dating violence (Baker & Stith, 2008; Shorey et al., 2014a). However, we are unaware of any research that has examined these two factors as potential moderators of the alcohol–dating violence association using a daily diary design.

The purpose of the present study was to examine whether trait anger and partner-specific anger management moderated the temporal relationship between alcohol (any and heavy drinking) and dating violence perpetration (psychological, physical, and sexual). We hypothesized that the temporal relationship between alcohol use and dating violence would be stronger for individuals high—relative to low—in trait anger and/or partner-specific anger management deficits. We tested this hypothesis using the same sample in which Shorey et al. (2014b) demonstrated the main effect of daily alcohol use on subsequent dating violence.

Method

Participants

Male undergraduate students from psychology courses were recruited for participation. Eligibility criteria included (a) being 18 years of age or older, (b) dating an individual who was 18 years of age or older for at least 1 month, (c) having drunk alcohol in the past month, and (d) having an average of 2 or more contact days (e.g., face-to-face) with their partner each week. Of 299 men screened, 170 students met the eligibility criteria and 103 (60.5%) agreed to participate in a 1-hour baseline session. Students were then invited to participate in the 90-day diary portion of the study. A total of 79 men (76.7%) began the daily diary portion, and the final sample consisted of 67 men who reported at least 1 face-to-face contact day with their partner.

As reported previously (Shorey et al., 2014b), participants reported a mean age of 19.74 (SD = 2.42) years and a mean relationship length of 14.20 (SD = 12.29) months. Approximately half of the sample were freshmen (44.8%), followed by sophomores (28.4%), juniors (11.9%), seniors (13.4%), and post-bachelor degree participants (1.5%). The majority of participants were European American (86.6%) and heterosexual (95.5%).

Baseline measures

Trait anger.

The trait anger subscale of the State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI; Spielberger, 1988) was used to assess trait anger. This subscale assesses a general tendency to become angry using 10 items on a scale from 1 (not at all or almost never) to 4 (very much so or almost always). A total score was calculated by summing all items such that higher scores correspond to greater trait anger. The internal consistency was .89.

Anger management.

The Anger Management Scale (AMS; Stith & Hamby, 2002) was used to examine partner-specific anger management. This 36-item scale assesses anger management as it relates to escalating strategies (cognitive and behavioral escalating responses to conflict), negative attributions (negative cognitions such as blame or harmful intentions attributed to one’s partner), self-awareness (level of awareness of changes representing increased anger), and calming strategies (use of strategies to calm down and deescalate when angry). Participants were instructed to think of their current dating partner when answering each item using a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). A total score was calculated by summing all items, and higher scores corresponded to better anger management. The internal consistency was .75.

Daily diary questions

Contact with partner.

Participants were asked if they had face-to-face contact with their partner the previous day.

Dating violence.

On days participants reported having face-to-face contact with their partner, participants answered questions regarding psychological, physical, and sexual dating violence using items from the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) using a “Yes/No” format. For each type of dating violence, every CTS2 item corresponding to that particular form of violence was presented to participants as two items (one for “minor” and one for “severe” violence for each subscale; Straus et al., 1996). Participants who reported perpetration were coded with a “1,” and participants who reported no perpetration were coded with a “0.” This was done for each type of dating violence separately.

Alcohol use.

Each day participants were asked if they consumed alcohol and whether they consumed alcohol before dating violence on days when violence occurred. If participants indicated that they consumed alcohol, they were asked to report the number of standard drinks they consumed and were provided with examples of a standard drink. Days on which participants drank alcohol and either did not perpetrate violence or drank alcohol before perpetrating violence were coded with a “1.” Days on which participants did not drink alcohol or drank alcohol after—but not before—violence were coded with a “0.” This same scoring procedure was repeated for heavy drinking days. On days when alcohol was consumed both before and after dating violence, only alcohol use before aggression was included. This method of coding alcohol is consistent with other daily diary studies on alcohol and intimate partner violence (e.g., Moore et al., 2011; Stuart et al., 2013).

Procedure

Participants first completed a 1-hour baseline assessment using an online survey website, which included an informed consent approved by the local institutional review board and evaluation of their trait anger and partner-specific anger management. Following the baseline assessment, participants received an email at 12:00 midnight with a link to that day’s daily survey, completed on Surveymonkey.com, for 90 consecutive days. If participants had not completed the daily survey by 5:00 p.m. each day, they were sent a reminder email with the survey link. Each set of surveys asked about their previous day’s behavior, defined as the time from when participants awoke until they went to sleep. Participants received 50 cents for each daily diary survey they completed and, if they completed at least 70% of the daily surveys, had the opportunity to win a $100.00 gift card.

Data analytic strategy

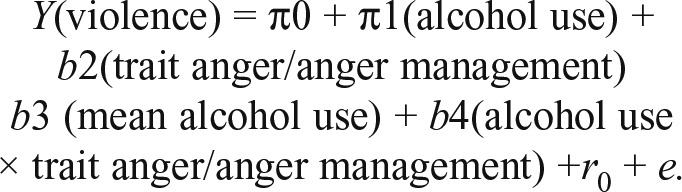

Given that daily reports were nested within individuals, we used multilevel modeling with HLM 7 (Raudenbush et al., 2011) to examine whether trait anger and/or anger management moderated the temporal association between alcohol and dating violence perpetration. Violence was regressed onto daily alcohol use in the first level of the model, the mean of alcohol use days (yes/no) across the study was entered in the second level of the model, and mean-centered trait anger/anger management scores were entered onto the intercept and slope in the second level of the model to create the following mixed-level equation:

|

Each indicator of alcohol use and each type of dating violence were examined separately. All alcohol use variables were uncentered, intercepts were random, slopes were fixed, and a Bernoulli sampling distribution was specified (given the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable). Significant interactions were decomposed at high (+1 SD) and low (-1 SD) levels of trait anger/anger management (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

As reported in Shorey et al. (2014b), participants completed a total of 3,441 daily surveys, for an overall compliance rate of 57%. A total of 1,833 days included face-to-face contact. Only face-to-face contact days were included in the current analyses to be consistent across forms of aggression. Across these days, 44 acts of psychological aggression (26.7% of sample), 23 acts of physical aggression (13.4% of sample), 18 acts of sexual aggression (11.8% of sample), 313 drinking days, and 153 heavy drinking days were reported.

On drinking days, men reported consuming an average of 5.60 (SD = 4.27) standard drinks and, on heavy drinking days, an average of 8.83 (SD = 3.79) drinks. Men reported that they had consumed alcohol before 18% of their psychological perpetration acts, 17% of their physical perpetration acts, and 38% of their sexual perpetration acts. Thus, there appears to be ample opportunity to examine whether associations between alcohol and aggression varied across anger management and trait anger. Also reported in Shorey et al. (2014b), the number of survey days completed was inversely related to physical and sexual aggression, but unrelated to psychological aggression. Trait anger and anger management were significantly correlated with each other (r = -.62, p < .001).

Trait anger moderated the temporal relationship between physical aggression perpetration and any alcohol use as well as heavy alcohol use (Table 1). Any alcohol use increased the odds of physical perpetration at high levels of trait anger (odds ratio [OR] = 2.48) but not at low levels of trait anger. Heavy alcohol use increased the odds of physical perpetration to a greater extent at high levels of trait anger (OR = 4.40) than at low levels of trait anger (OR = 2.42).

Table 1.

Moderating effect of trait anger on the relationship between alcohol use and aggression perpetration

| Variable | χ2 | t | B | SE | OR | [CI] |

| Psychological aggression perpetration | ||||||

| Intercept | 134.27*** | |||||

| Mean any alcohol use | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.93 | 1.18 | [0.18, 7.72] | |

| Any alcohol use | -0.83 | -0.18 | 0.22 | 0.83 | [0.53, 1.28] | |

| Trait anger | 5.05*** | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.10 | [1.06, 1.15] | |

| Alcohol Use × TraitAnger | -0.02 | -0.00 | 0.02 | 0.99 | [0.96, 1.03] | |

| Intercept | 133.39*** | |||||

| Mean heavy alcohol use | -0.03 | -0.03 | 1.04 | 0.97 | [0.11, 7.92] | |

| Heavy alcohol use | 0.57 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 1.12 | [0.75, 1.67] | |

| Trait anger | 4.74*** | 0.10 | 0.02 | 1.10 | [1.06, 1.15] | |

| Heavy Alcohol Use × Trait Anger | -1.02 | -0.02 | 0.02 | 0.98 | [0.95, 1.01] | |

| Physical aggression perpetration | ||||||

| Intercept | 85.64* | |||||

| Mean any alcohol use | -0.27 | -0.18 | 0.69 | 0.82 | [0.21, 3.31] | |

| Any alcohol use | 4.74*** | 0.72 | 0.15 | 2.06 | [1.56, 2.77 | |

| Trait anger | 4.66*** | 0.06 | 0.01 | 1.06 | [1.03, 1.09] | |

| Alcohol Use × Trait Anger | 2.74** | 0.06 | 0.02 | 1.06 | [1.01, 1.10] | |

| High trait anger | 5.39*** | 0.91 | 0.17 | 2.48 | [1.78, 3.46] | |

| Low trait anger | 0.87 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 1.22 | [0.77, 1.94] | |

| Intercept | 91.47** | |||||

| Mean heavy alcohol use | 1.32 | 1.44 | 1.09 | 4.25 | [0.47, 38.15] | |

| Heavy alcohol use | 8.60*** | 1.31 | 0.15 | 3.72 | [2.76, 5.02] | |

| Trait anger | 4.30*** | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1.05 | [1.03, 1.08] | |

| Heavy Alcohol Use × Trait Anger | 2.04* | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.05 | [1.00, 1.10] | |

| High trait anger | 7.62*** | 1.48 | 0.19 | 4.40 | [3.00, 6.45] | |

| Low trait anger | 3.84*** | 0.88 | 0.23 | 2.42 | [1.54, 3.80] | |

| Sexual aggression perpetration | ||||||

| Intercept | 76.22 | |||||

| Mean any alcohol use | 1.27 | 1.16 | 0.92 | 3.21 | [0.51, 20.21] | |

| Any alcohol use | 4.93*** | 1.30 | 0.26 | 3.70 | [2.20, 6.23] | |

| Trait anger | 1.15 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.02 | [0.99, -1.06] | |

| Alcohol Use × Trait Anger | 1.83 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.06 | [0.99, 1.14] | |

| Intercept | 86.64* | |||||

| Mean heavy alcohol use | 1.35 | 1.48 | 1.09 | 4.41 | [0.49, 39.51] | |

| Heavy alcohol use | 2.44* | 0.65 | 0.26 | 1.93 | [1.14, 3.27] | |

| Trait anger | 1.99* | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.03 | [1.00, 1.08] | |

| Heavy Alcohol Use × Trait Anger | -6.25*** | -0.12 | 0.01 | 0.88 | [0.85, 0.92] | |

| High trait anger | 0.77 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 1.22 | [0.74, 2.01] | |

| Low trait anger | 7.57*** | 1.66 | 0.21 | 5.27 | [3.42, 8.10] |

Notes: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Trait anger also moderated the temporal relationship between heavy alcohol use and sexual aggression perpetration, but in a different manner (Table 1). Heavy alcohol use increased the odds of sexual perpetration at low levels of trait anger (OR = 5.27) but not at high levels of trait anger.

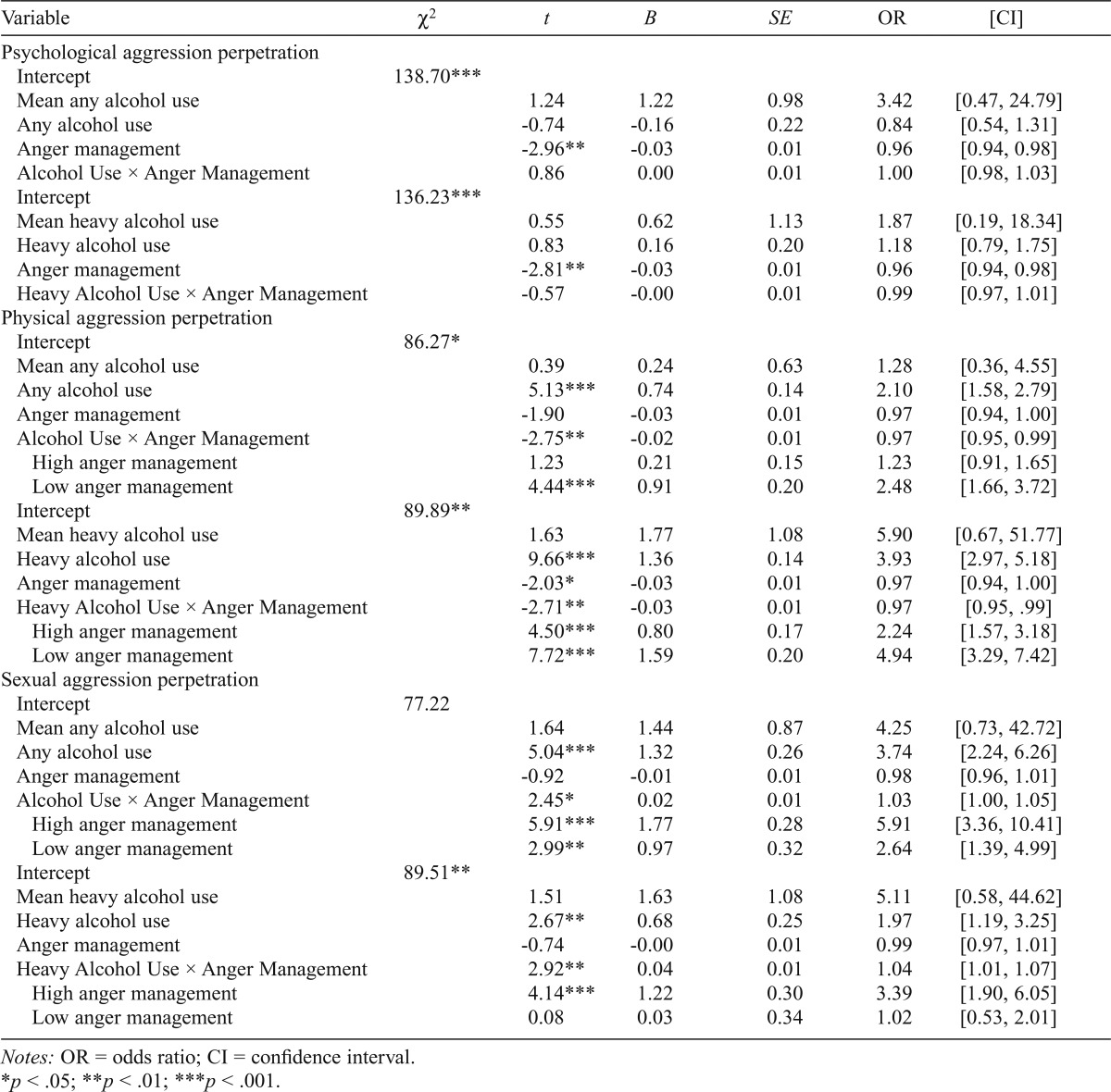

Anger management moderated the relationship between alcohol use (any use and heavy use) and physical aggression perpetration (Table 2). Any alcohol use increased the odds of physical perpetration at low levels of anger management (OR = 2.48) but not at high levels of anger management. Likewise, heavy alcohol use was more strongly associated with increased odds of physical perpetration when anger management was low (OR = 4.94) relative to high (OR = 2.24), although both simple effects were significant.

Table 2.

Moderating effect of anger management on the relationship between alcohol use and aggression perpetration

| Variable | χ2 | t | B | SE | OR | [CI] |

| Psychological aggression perpetration | ||||||

| Intercept | 138.70*** | |||||

| Mean any alcohol use | 1.24 | 1.22 | 0.98 | 3.42 | [0.47, 24.79] | |

| Any alcohol use | -0.74 | -0.16 | 0.22 | 0.84 | [0.54, 1.31] | |

| Anger management | -2.96** | -0.03 | 0.01 | 0.96 | [0.94, 0.98] | |

| Alcohol Use × Anger Management | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | [0.98, 1.03] | |

| Intercept | 136.23*** | |||||

| Mean heavy alcohol use | 0.55 | 0.62 | 1.13 | 1.87 | [0.19, 18.34] | |

| Heavy alcohol use | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 1.18 | [0.79, 1.75] | |

| Anger management | -2.81** | -0.03 | 0.01 | 0.96 | [0.94, 0.98] | |

| Heavy Alcohol Use × Anger Management | -0.57 | -0.00 | 0.01 | 0.99 | [0.97, 1.01] | |

| Physical aggression perpetration | ||||||

| Intercept | 86.27* | |||||

| Mean any alcohol use | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.63 | 1.28 | [0.36, 4.55] | |

| Any alcohol use | 5.13*** | 0.74 | 0.14 | 2.10 | [1.58, 2.79] | |

| Anger management | -1.90 | -0.03 | 0.01 | 0.97 | [0.94, 1.00] | |

| Alcohol Use × Anger Management | -2.75** | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.97 | [0.95, 0.99] | |

| High anger management | 1.23 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 1.23 | [0.91, 1.65] | |

| Low anger management | 4.44*** | 0.91 | 0.20 | 2.48 | [1.66, 3.72] | |

| Intercept | 89.89** | |||||

| Mean heavy alcohol use | 1.63 | 1.77 | 1.08 | 5.90 | [0.67, 51.77] | |

| Heavy alcohol use | 9.66*** | 1.36 | 0.14 | 3.93 | [2.97, 5.18] | |

| Anger management | -2.03* | -0.03 | 0.01 | 0.97 | [0.94, 1.00] | |

| Heavy Alcohol Use × Anger Management | -2.71** | -0.03 | 0.01 | 0.97 | [0.95, .99] | |

| High anger management | 4.50*** | 0.80 | 0.17 | 2.24 | [1.57, 3.18] | |

| Low anger management | 7.72*** | 1.59 | 0.20 | 4.94 | [3.29, 7.42] | |

| Sexual aggression perpetration | ||||||

| Intercept | 77.22 | |||||

| Mean any alcohol use | 1.64 | 1.44 | 0.87 | 4.25 | [0.73, 42.72] | |

| Any alcohol use | 5.04*** | 1.32 | 0.26 | 3.74 | [2.24, 6.26] | |

| Anger management | -0.92 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.98 | [0.96, 1.01] | |

| Alcohol Use x Anger Management | 2.45* | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.03 | [1.00, 1.05] | |

| High anger management | 5.91*** | 1.77 | 0.28 | 5.91 | [3.36, 10.41] | |

| Low anger management | 2.99** | 0.97 | 0.32 | 2.64 | [1.39, 4.99] | |

| Intercept | 89.51** | |||||

| Mean heavy alcohol use | 1.51 | 1.63 | 1.08 | 5.11 | [0.58, 44.62] | |

| Heavy alcohol use | 2.67** | 0.68 | 0.25 | 1.97 | [1.19, 3.25] | |

| Anger management | -0.74 | -0.00 | 0.01 | 0.99 | [0.97, 1.01] | |

| Heavy Alcohol Use x Anger Management | 2.92** | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.04 | [1.01, 1.07] | |

| High anger management | 414*** | 1.22 | 0.30 | 3.39 | [1.90, 6.05] | |

| Low anger management | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 1.02 | [0.53, 2.01] |

Notes: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Anger management also moderated the temporal association between alcohol use (any use and heavy use) and sexual aggression perpetration (Table 2), but again in a different manner. Any alcohol use was more strongly associated with the odds of sexual perpetration when anger management was high (OR = 5.91) relative to low (OR = 2.64), although both simple effects were significant. Likewise, heavy alcohol use increased the odds of perpetration when anger management was high (OR = 3.39) but not when anger management was low.1,2,3

Discussion

Our findings partially supported the theoretical supposition that alcohol use would be particularly likely to lead to dating violence among individuals with low thresholds for aggression. At high levels of trait anger and low levels of anger management, increased alcohol use was associated with increased odds of physical aggression perpetration. The association was either minimized or nonsignificant at low levels of trait anger and high levels of anger management.

These findings lend continued support to the idea that alcohol use needs to be targeted in dating violence intervention and prevention programs (Shorey et al., 2011), which has received scant attention in these programs to date (Shorey et al., 2012). In addition, our findings suggest that such interventions may have the greatest impact on reducing violence if they focus their intervention efforts on men with low anger management and/or high trait anger.

Trait anger and anger management did not moderate the effects of alcohol use on psychological aggression. Further, in contrast to predictions, increased alcohol use and heavy use were more strongly associated with increased sexual aggression perpetration at low levels of trait anger and high levels of anger management. One explanation for this counterintuitive finding is that sexual dating violence may be a more proactive and planned behavior, whereas physical dating violence may be attributable more to anger and anger management deficits, which are exacerbated when under the influence of alcohol. That is, perpetrators may be more likely to use physical aggression when intoxicated and high in trait anger/anger management deficits, which may represent more impulsive, reactive aggression. In contrast, having low trait anger/anger management deficits may facilitate sexual aggression when intoxicated, as men may be more focused on feelings and thoughts of sexual arousal (relative to anger). Indeed, there is some research to suggest that sexual aggression may be motivated by sexual gratification (e.g., Reid et al., 2014), although other research suggests it may be motivated by anger (e.g., Lisak, 2008). Future research is needed to examine this further in the context of alcohol use.

Several limitations should be noted. Generalizability is limited because of the homogeneous sample of college men and small sample size. Partner reports of alcohol use and dating violence were not obtained; future research would be improved by including both dyad members. Although similar to that obtained in other 90-day daily diary research (Sullivan et al., 2012), our daily diary compliance rate was somewhat low. Reactivity to assessment is a concern given the length of the daily assessments and findings that the number of surveys completed was inversely associated with physical and sexual aggression. Last, information about individuals who qualified for the study but chose not to complete the study was not collected.

Footnotes

Although previous research demonstrates that negative affect and emotion regulation interact to predict dating violence in this sample (Shorey et al., 2015), the effects reported in this article remained significant when those interactive effects were controlled for.

We also conducted analyses with a contrast between no alcohol use and alcohol use, and a contrast between any alcohol use and heavy alcohol use simultaneously. This model would not converge for physical aggression. Results for sexual aggression demonstrated that trait anger continued to moderate for any alcohol and heavy alcohol, and anger management only moderated for heavy alcohol use. A significant interaction was observed for anger management and any alcohol use and heavy alcohol use with psychological aggression, although decomposition of the interaction demonstrated no significant effects.

For the models examining any alcohol use and sexual aggression perpetration, the intercepts did not significantly vary across individuals. When we ran those models with fixed intercepts, the results for trait anger remained consistent. For anger management, however, there was no longer a significant interaction between any alcohol use and anger management in predicting sexual perpetration.

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baker C. R., Stith S. M. Factors predicting dating violence perpetration among male and female college students. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2008;17:227–244. doi:10.1080/10926770802344836. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C. I., Crane C. Effects of alcohol intoxication and aggressivity on aggressive verbalizations during anger arousal. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:428–36. doi: 10.1002/ab.20249. doi:10.1002/ab.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W., Leonard K. E., Birchler G. R. The occurrence of male-to-female intimate partner violence on days of men’s drinking: The moderating effects of antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:239–248. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.239. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel E. J., DeWall C. N., Slotter E. B., McNulty J. K., Pond R. S., Jr., Atkins D. C. Using I3 theory to clarify when dispositional aggressiveness predicts intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102:533–549. doi: 10.1037/a0025651. doi:10.1037/a0025651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran H. M., O’Leary K. D. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola P. R. Executive functioning: A conceptual framework for alcohol-related aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:576–597. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.576. doi:10.1037/1064–1297.8.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola P. R. The influence of trait anger on the alcohol-aggression relation in men and women. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:1350–1358. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000030842.77279.C4. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola P. R., Levinson C. A., Corman M. D., Godlaski A. J., Morris D. H., Phillips J. P., Holt J. C. Men and women, alcohol and aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:154–164. doi: 10.1037/a0016385. doi:10.1037/a0016385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola P. R., Parrott D. J., Silvia P. J., DeWall C. N., Begue L., Subra B., Bushman B. J. The disguise of sobriety: Unveiled by alcohol in persons with an aggressive personality. Journal of Personality. 2012;80:163–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00726.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K. E. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: When can we say that heavy drinking is a contributing cause of violence? Addiction. 2005;100:422–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00994.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisak D. Understanding the predatory nature of sexual violence. 2008 Retrieved from http://ocadvsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Understanding-the-Predatory-Nature-of-Sexual-Violence.pdf.

- Moore T. M., Elkins S. R., McNulty J. K., Kivisto A. J, Handsel V. A. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: Assessing the temporal association using electronic diary technology. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1:315–328. doi:10.1037/a0025077. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Rockville, MD: Author; 1995. The physicians’guide to helping patients with alcohol problems (NIH Publication No. 95–3769) [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S. W., Bryk A. S., Cheong Y. F., Congdon R., du Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincoln-wood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reid J. A., Beauregard E., Fedina K. M., Frith E. N. Employing mixed methods to explore motivational patterns of repeat sex offenders. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2014;42:203–212. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.06.008. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Cornelius T. L., Idema C. Trait anger as a mediator of difficulties with emotion regulation and female-perpetrated psychological aggression. Violence and Victims. 2011;26:271–282. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.26.3.271. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.26.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., McNulty J. K., Moore T. M., Stuart G. L. Emotion regulation moderates the association between proximal negative affect and intimate partner violence perpetration. Prevention Science. 2015;16:873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0568-5. doi:10.1007/s11121-015-0568-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Seavey A. E., Quinn E., Cornelius T. L. Partner-specific anger management as a mediator of the relation between mindfulness and female perpetrated dating violence. Psychology ofViolence. 2014a;4:51–64. doi: 10.1037/a0033658. doi:10.1037/a0033658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Stuart G. L., McNulty J. K., Moore T. M. Acute alcohol use temporally increases the odds of male perpetrated dating violence: A 90-day diary analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2014b;39:365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Zucosky H., Brasfield H., Febres J., Cornelius T. L., Sage C., Stuart G. L. Dating violence prevention programming: Directions for future interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.001. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. D. State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). Research edition. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck C. A., Fromme K. The effects of alcohol, emotion regulation, and emotional arousal on the dating aggression intentions of men and women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:10–19. doi: 10.1037/a0032204. doi:10.1037/a0032204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith S. M., Hamby S. L. The Anger Management Scale: Development and preliminary psychometric properties. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:383–402. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.4.383.33683. doi:10.1891/vivi.17.4.383.33683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A., Hamby S. L., Boney-McCoy S., Sugarman D. B. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi:10.1177/019251396017003001. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G. L., Moore T. M., Elkins S. R., O’Farrell T. J., Temple J. R., Ramsey S. E., Shorey R. C. The temporal association between substance use and intimate partner violence among women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:681–690. doi: 10.1037/a0032876. doi:10.1037/a0032876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T. P., McPartland T., Armeli S., Jaquier V, Tennen H. Is it the exception or the rule? Daily co-occurrence of physical, sexual, and psychological partner violence in a 90-day study of substance-using, community women. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:154–164. doi: 10.1037/a0027106. doi:10.1037/a0027106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft C. T., Schumm J., Orazem R. J., Meis L., Pinto L. A. Examining the link between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and dating aggression perpetration. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:456–469. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.456. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]