Abstract

The basidiomycete Heterobasidion annosum sensu lato (s.l.) is considered to be one of the most destructive conifer pathogens in the temperate forests of the northern hemisphere. H. annosum is characterized by a dual fungal lifestyle. The fungus grows necrotrophically on living plant cells and saprotrophically on dead wood material. In this study, we screened the H. annosum genome for small secreted proteins (HaSSPs) that could potentially be involved in promoting necrotrophic growth during the fungal infection process. The final list included 58 HaSSPs that lacked predictable protein domains. The transient expression of HaSSP encoding genes revealed the ability of 8 HaSSPs to induce cell chlorosis and cell death in Nicotiana benthamiana. In particular, one protein (HaSSP30) could induce a rapid, strong, and consistent cell death within 2 days post-infiltration. HaSSP30 also increased the transcription of host-defence-related genes in N. benthamiana, which suggested a necrotrophic-specific immune response. This is the first line of evidence demonstrating that the H. annosum genome encodes HaSSPs with the capability to induce plant cell death in a non-host plant.

Introduction

The basidiomycete Heterobasidion annosum sensu lato (s.l.) is a necrotrophic fungal pathogen of conifer trees1. H. annosum s.l. exists as a species complex with three European species, H. annosum sensu stricto (s.s.), H. parviporum, and H. abietinum, and two north American species, H. irregulare and H. occidentale 2. While H. abietinum is found mostly in the Mediterranean area, infecting conifer species of the genus Abies, H. parviporum and H. annosum s.s. are found in northern Europe, infecting mainly Norway spruce and Scots pine, respectively3, 4. The H. annosum s.l. initially infects hosts through stump colonization mediated by basidiospores. The fungus from infected trees spreads to healthy trees by root-to-root contact5. The fungal infection compromises the timber quality, causing an estimated economic loss of approximately 790 million euros per year in Europe alone4. A major feature of this pathogen is the ability to switch from a saprotrophic (i.e., feeding on wood material) to a necrotrophic lifestyle when it encounters living cells in the sapwood of infected conifer trees.

In nature, forest trees and crop plants are constantly challenged by a wide variety of pathogens, including fungi, oomycetes, viruses, and bacteria. Because plants are sessile organisms unable to evade the attacker by simply moving away, they have developed a sophisticated immune system. Plants respond to microbial invaders by coordinating the actions of several elements of the plant immune system6. In the classic plant-microbe interaction model, invading pathogens possess pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) which are recognized by specific plant pattern recognition receptors (PRRs); the recognition between a PAMP and its cognate PRR triggers an immune response defined as PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI). However, the PTI response is attenuated by the secretion of microbial effectors that suppress the plant immune system to promote host colonization6. The highly specific recognition between a plant resistance protein (R protein) and the pathogen effector follows the gene-for-gene interaction hypothesis and culminates with the plant’s programmed cell death (PCD) or hypersensitive response (HR) mechanisms7.

Plant pathogenic fungi are divided primarily into biotrophs, hemibiotrophs, and necrotrophs based on their mode of infection and host colonization. Biotrophs are so defined because they feed on living plant tissue. In contrast, necrotrophs rapidly kill the host tissue and feed on dead plant material. Hemibiotrophs are similar to both in that they are characterized by an initial biotrophic phase followed by a switch to a necrotrophic phase during late infection.

Fungal plant pathogens colonize the host by secreting a wide array of fungal effectors8. Most of the research related to the functional characterization of fungal effectors has been performed using biotrophic and hemibiotrophic fungi. Since the first fungal plant pathogen genome (Magnaporthe oryzae) was sequenced9, several studies have been published elucidating the mechanisms of action of biotrophic fungal effectors. For example, several fungal effector proteins bind and mask chitin to prevent triggering the plant immune response. Examples of these effectors are as follows: Cladosporium fulvum Ecp6, which binds chitin oligomers10; C. fulvum Avr4, which masks the chitin of the fungal cell wall to protect it from the plant chitinases11; and M. oryzae Slp1, which has chitin binding properties12. Other fungal effectors can target and inhibit the cellular proteases that are important for the plant immune response. For example, U. maydis Pit2 and C. fulvum Avr2 bind and inhibit several plant cysteine-proteases13, 14.

Very little is known about the mechanisms of action of necrotrophic fungal effectors. Necrotrophic fungi have historically been considered unspecialized and unsophisticated plant pathogens that can only secrete cell wall degrading enzymes (CWDE) to induce nonspecific cell death by compromising plant cell wall integrity15. However, several lines of evidence demonstrate that necrotrophic fungi can produce and secrete specific proteins that specifically interact with components of the plant immune system. In particular, necrotrophic fungi can secrete host specific toxins (HST) that are defined as necrotrophic effectors16, 17. Much of what we know about these effectors stems from studies characterizing the crop pathogens Stagonospora nodorum and Pyrenophora tritici-repentis, which are two necrotrophic fungi of wheat responsible for the Stagonospora nodorum blotch (SNB) and tan spot, respectively17. The first HST to be characterized was ToxA, a pathogenicity factor of P. tritici-repentis, which is responsible for the fungal necrotrophic growth in wheat (Triticum aestivum)18. There is much less literature describing necrotrophic effectors than biotrophic parasites, and most available information is primarily related to agricultural crop pathogens. Additionally, the data available on necrotrophic effectors for forest pathogenic fungi is limited19, 20.

To date, effectors for the necrotrophic fungus H. annosum s.l. have not been identified. The availability of the sequenced and annotated genome of H. annosum strain TC32-1 provided the opportunity to screen for putative fungal necrotrophic effectors21. This study provides the first line of evidence that the H. annosum genome encodes small secreted proteins (HaSSPs) with the ability to induce plant cell death in the plant model system N. benthamiana.

Results

Genome mining for candidate H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSP)- encoding genes and assessment of gene expression

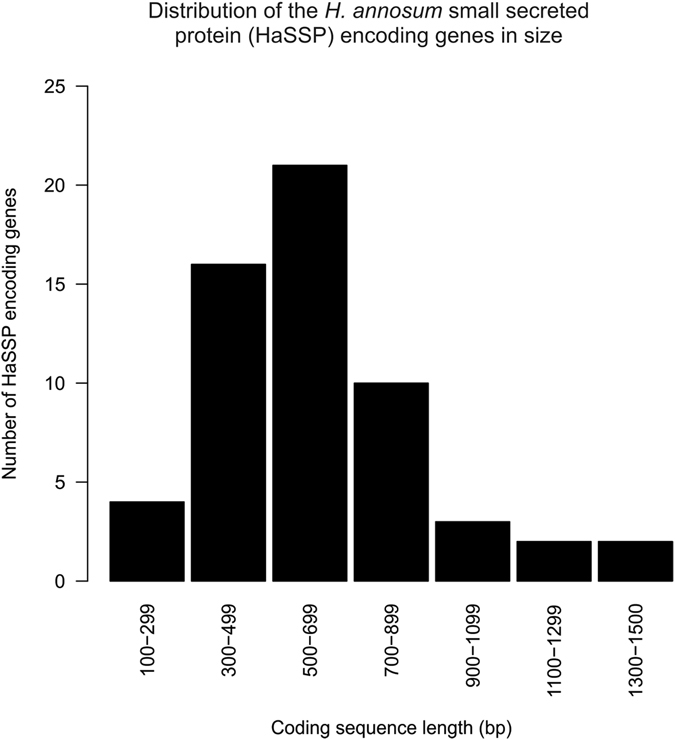

Fifty-eight putative HaSSP encoding genes were retrieved from the genome of H. annosum strain TC 32-1 (Table 1). The shortest candidate gene was 174 nucleotides (nt) long [Protein ID (Hetan2) 328808, 58 AA], while the longest was 1428 nt long [Protein ID (Hetan2) 441917, 476 AA]. The length of most of the candidate effector genes was between 300 nt and 900 nt (Fig. 1), and the HaSSP proteins selected for this study did not include any predicted protein domains. The number of disulfide bridges ranged between 1 and 8 [Protein ID (Hetan2) 482211, 442 AA]. Twenty-three HaSSP-encoding genes were characterized by expressed sequence tags (EST) support in the H. annosum TC 32-1 genome browser (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSP) encoding genes retrieved from the H. annosum TC 32-1 genome annotation.

| HaSSP candidate number | Protein ID (Hetan1)1 | Protein ID (Hetan2.0)1 | Gene name (Hetan2)1 | Length (bp) | Length (AA) | Protein ID | Cys-Cys bonds number | EST support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58748 | 58748 | Hetan1.estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_10476 | 585 | 195 | 58748 | 5 | YES |

| 2 | 99056 | 99056 | Hetan1.Genemark.129_g | 900 | 300 | 99056 | 5 | NO |

| 3 | 101504 | 101504 | Hetan1.Genemark.2577_g | 468 | 156 | 101504 | 1 | NO |

| 4 | 102625 | 102625 | Hetan1.Genemark.3698_g | 351 | 117 | 102625 | 1 | NO |

| 5 | 102999 | 102999 | Hetan1.Genemark.4072_g | 615 | 205 | 102999 | 2 | NO |

| 6 | 103544 | 103544 | Hetan1.Genemark.4617_g | 582 | 194 | 103544 | 2 | NO |

| 7 | 106199 | 106199 | Hetan1.Genemark.7272_g | 645 | 215 | 106199 | 2 | NO |

| 8 | 106204 | 106204 | Hetan1.Genemark.7277_g | 339 | 113 | 106204 | 1 | NO |

| 9 | 107400 | 107400 | Hetan1.Genemark.8473_g | 387 | 129 | 107400 | 1 | NO |

| 10 | 107522 | 107522 | Hetan1.Genemark.8595_g | 483 | 161 | 107522 | 2 | NO |

| 11 | 108275 | 108275 | Hetan1.Genemark.9348_g | 1233 | 411 | 108275 | 4 | NO |

| 12 | 108527 | 108527 | Hetan1.Genemark.9600_g | 432 | 144 | 108527 | 3 | NO |

| 13 | 109064 | 109064 | Hetan1.Genemark.10137_g | 558 | 186 | 109064 | 5 | YES |

| 14 | 118007 | 118007 | Hetan1.fgenesh2_pg.C_scaffold_7000137 | 744 | 248 | 118007 | 1 | YES |

| 15 | 119220 | 119220 | Hetan1.fgenesh2_pg.C_scaffold_10000169 | 822 | 274 | 119220 | 2 | NO |

| 16 | 120415 | 120415 | Hetan1.fgenesh2_pg.C_scaffold_13000272 | 741 | 247 | 120415 | 2 | NO |

| 17 | 120417 | 120417 | Hetan1.fgenesh2_pg.C_scaffold_13000274 | 453 | 151 | 120417 | 1 | NO |

| 18 | 120417 | 120798 | Hetan1.fgenesh2_pg.C_scaffold_15000086 | 606 | 202 | 120798 | 1 | NO |

| 19 | 157644 | 157644 | Hetan1.estExt_fgenesh2_pm.C_130199 | 453 | 151 | 157644 | 2 | YES |

| 20 | 162925 | 162925 | Hetan1.EuGene10000530 | 222 | 74 | 162925 | 2 | NO |

| 21 | 163365 | 163365 | Hetan1.EuGene11000336 | 306 | 102 | 163365 | 3 | NO |

| 22 | 173217 | 173217 | Hetan1.EuGene7000278 | 327 | 109 | 173217 | 5 | YES |

| 23 | 174683 | 174683 | Hetan1.EuGene9000335 | 273 | 91 | 174683 | 4 | NO |

| 24 | 116393 | 312085 | e_gw1.03.1544.1 | 618 | 206 | 312085 | 2 | NO |

| 25 | 34813 | 314110 | e_gw1.03.1702.1 | 471 | 157 | 314110 | 3 | YES |

| 26 | 104923 | 317287 | e_gw1.05.2448.1 | 1092 | 364 | 317287 | 2 | NO |

| 27 | 25033 | 318819 | e_gw1.05.2082.1 | 798 | 266 | 318819 | 1 | NO |

| 28 | 55873 | 326012 | e_gw1.09.1661.1 | 720 | 240 | 326012 | 4 | NO |

| 29 | NA | 328808 | e_gw1.11.1302.1 | 174 | 58 | 328808 | 3 | NO |

| 30 | 164295 | 391204 | estExt_Genewise1.C_131090 | 534 | 178 | 391204 | 1 | YES |

| 31 | NA | 414262 | fgenesh1_pm.02_#_149 | 417 | 139 | 414262 | 3 | YES |

| 32 | 115627 | 418080 | fgenesh1_pm.05_#_676 | 372 | 124 | 418080 | 2 | NO |

| 33 | 169544 | 418760 | fgenesh1_pm.06_#_505 | 336 | 112 | 418760 | 4 | YES |

| 34 | 162746 | 422598 | fgenesh1_pm.12_#_283 | 492 | 164 | 422598 | 3 | NO |

| 35 | 108551 | 423383 | fgenesh1_pm.14_#_116 | 378 | 126 | 423383 | 2 | NO |

| 36 | 116836 | 425913 | fgenesh1_pg.03_#_659 | 813 | 271 | 425913 | 4 | NO |

| 37 | NA | 425924 | fgenesh1_pg.03_#_670 | 891 | 297 | 425924 | 2 | NO |

| 38 | 154711 | 427282 | fgenesh1_pg.05_#_541 | 795 | 265 | 427282 | NA | YES |

| 39 | 115568 | 427322 | fgenesh1_pg.05_#_581 | 726 | 242 | 427322 | 2 | NO |

| 40 | 152005 | 429704 | fgenesh1_pg.10_#_299 | 525 | 175 | 429704 | 3 | NO |

| 41 | 120216 | 430810 | fgenesh1_pg.13_#_214 | 507 | 169 | 430810 | 1 | NO |

| 42 | 145189 | 431393 | estExt_fgenesh1_pm.C_010330 | 798 | 266 | 431393 | 1 | YES |

| 43 | 108765 | 439412 | estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_040024 | 306 | 102 | 439412 | 2 | YES |

| 44 | 148537 | 439593 | estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_040240 | 696 | 232 | 439593 | 1 | YES |

| 45 | 147795 | 441917 | estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_100319 | 1428 | 476 | 441917 | 4 | YES |

| 46 | 148061 | 442002 | estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_110095 | 603 | 201 | 442002 | 5 | YES |

| 47 | NA | 447006 | estExt_fgenesh1_pg.C_130285 | 660 | 220 | 447006 | 1 | YES |

| 48 | 157214 | 450757 | Genemark.3585_g | 582 | 194 | 450757 | 1 | NO |

| 49 | 104830 | 451269 | Genemark.4097_g | 642 | 214 | 451269 | 4 | NO |

| 50 | 103839 | 452658 | Genemark.5486_g | 627 | 209 | 452658 | 2 | NO |

| 51 | 103483 | 452993 | Genemark.5821_g | 537 | 179 | 452993 | 3 | YES |

| 52 | NA | 456226 | Genemark.9054_g | 618 | 206 | 456226 | 2 | YES |

| 53 | 146303 | 459335 | estExt_Genemark.C_060269 | 216 | 72 | 459335 | 4 | YES |

| 54 | 108486 | 461461 | estExt_Genemark.C_140166 | 1011 | 337 | 461461 | 4 | NO |

| 55 | 168056 | 470877 | estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_021603 | 252 | 84 | 470877 | 2 | YES |

| 56 | 104047 | 477946 | estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_080375 | 465 | 155 | 477946 | 2 | YES |

| 57 | 107965 | 482211 | estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_130878 | 1326 | 442 | 482211 | 8 | YES |

| 58 | 165012 | 482547 | estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_140371 | 627 | 209 | 482547 | 4 | YES |

Figure 1.

Distribution of the length of the H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSP) encoding genes as retrieved from the H. annosum TC 32-1 genome annotation.

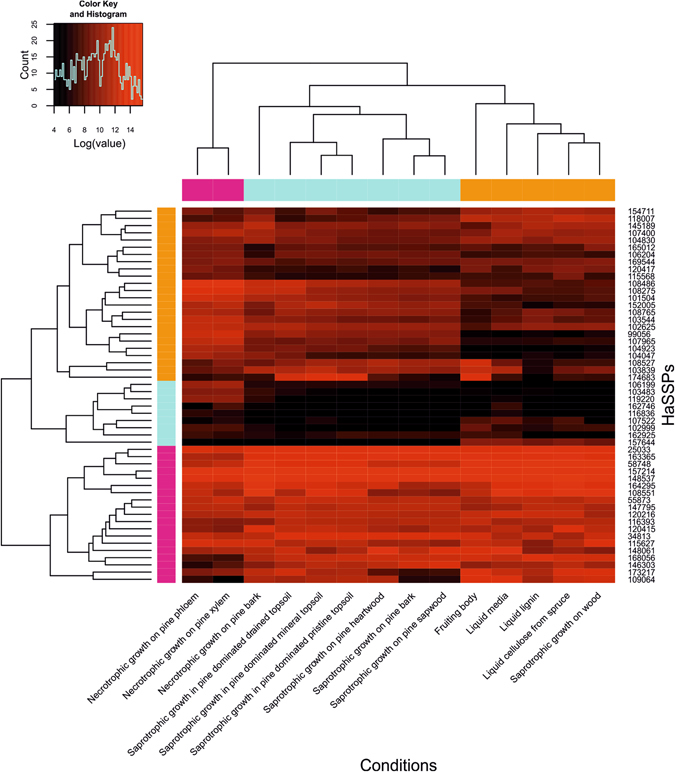

The transcriptomic data available for H. annosum in the GEO database were collected from samples grown under different conditions and substrates. These data revealed that the selected HaSSP-encoding genes displayed a characteristic variation in their expression levels (Fig. 2). In particular, sample cluster analysis revealed a single separated cluster for the samples related to the fungal necrotrophic growth on pine phloem and xylem (“Necrotrophic growth on pine phloem” and “Necrotrophic growth on pine xylem”, pink cluster, Fig. 2). All the samples related to saprotrophic growth on pine sapwood, heartwood and bark, together with the sample related to necrotrophic growth on pine bark, formed a separate cluster (light blue cluster, Fig. 2). Finally, all the samples related to growth on liquid media together with the samples from the H. annosum fruiting body and saprotrophic growth on whole wood formed another separate cluster (orange cluster, Fig. 2). The three clusters described above were statistically significant, as shown by the multiscale bootstrap resampling analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1). The multiscale bootstrap resampling analysis revealed approximately unbiased (au) values of 100, 96, and 92 for the necrotrophic, saprotrophic, and liquid clusters, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

Microarray gene expression levels of the selected H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSP) encoding genes in different conditions. Microarray data were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Raw data were normalized and analysed with the statistical R programme48 using oligo 49 and gplots 50 packages.

The cluster analysis of the HaSSP-encoding genes revealed three main transcript groups. The first cluster was characterized by high gene expression levels (pink cluster, Fig. 2), the second was characterized by low gene expression levels (light blue cluster, Fig. 2), and finally, the third was characterized by intermediate gene expression levels (orange cluster, Fig. 2). The three gene clusters were also statistically significant as shown by the multiscale bootstrap resampling analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2). The analysis revealed an approximately unbiased (au) value of 89, 97, and 97 for the high, low and intermediate gene expression level clusters, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Transient expression of the selected H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSP)- encoding genes in Nicotiana benthamiana by agroinfiltration

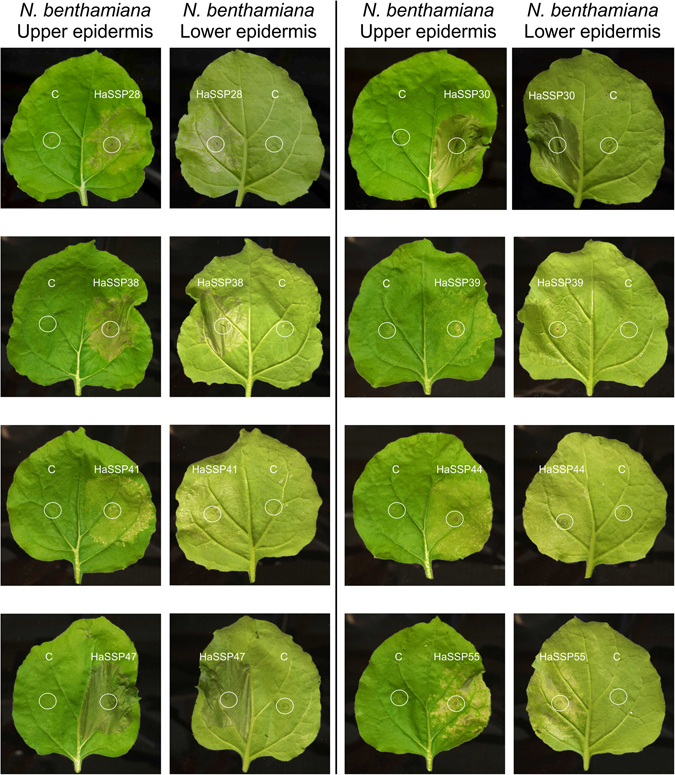

Eight constructs out of the 58 H. annosum HaSSP-encoding genes tested in this study induced chlorosis and cell death when transiently expressed in N. benthamiana by agroinfiltration (Fig. 3). Plant cell death was characterized by large necrotic spots, thinning, and overall compromised tissue integrity compared to the control, which showed no symptoms. In particular, HaSSP28, HaSSP38, HaSSP39, HaSSP41, HaSSP44, and HaSSP55 induced a certain level of chlorosis and cell death between 3 to 6 days post-infiltration (dpi). However, HaSSP30 and HaSSP47 induced a rapid and more pronounced cell death as early as 2 dpi and total loss of leaf turgidity at 4 dpi. Following sequence analysis, HaSSP30 and HaSSP47 were found to represent two different gene isoforms (ID391204 and ID447006 respectively, Table 1) but denoted the same protein predicted in the H. annosum TC 32-1 genome. The two predicted proteins only differed due to an extra fragment of 45 amino acids at the C-terminus of HaSSP47 (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 3.

Chlorosis and cell death induced by transient expression of the H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSS) encoding genes in Nicotiana benthamiana. HaSSPs were custom synthesised into the pUC57 vector. Each candidate gene was cloned into the pICH86988 expression vector by Golden Gate cloning, generating pICH86988-HaSSP. The vector was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 followed by agroinfiltration into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. The plants were incubated in a growth room with 12 h/12 h, night/day photoperiods at 20–24 °C and 60% relative humidity (RH). The infiltrated leaves were monitored for 2 to 6 days post-infiltration (dpi).

Activation of selected N. benthamiana immune system genes by HaSSP30

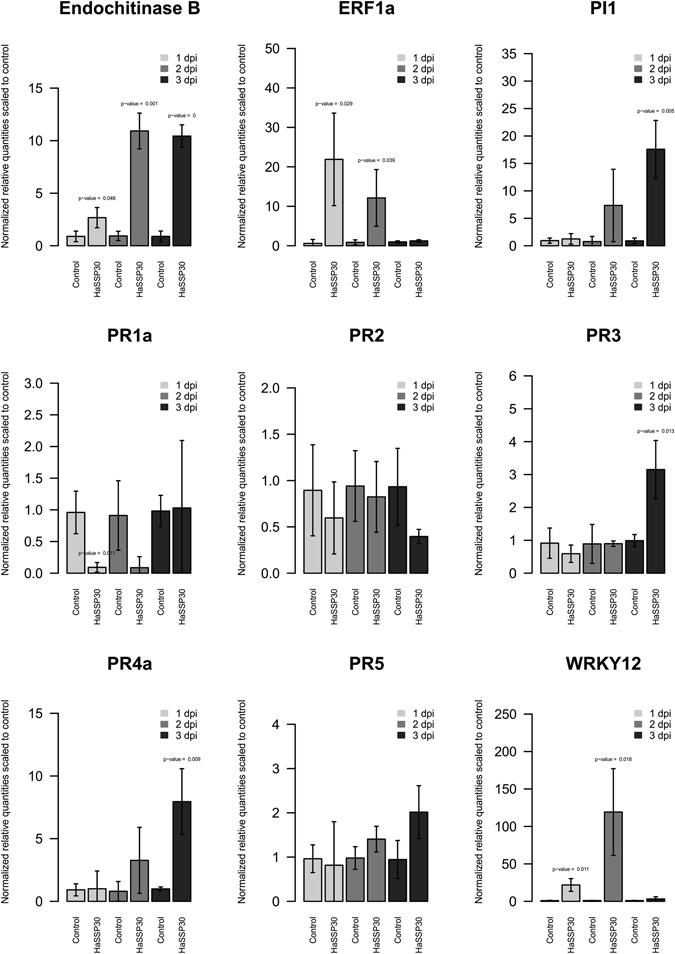

The expression levels of several genes related to the activation of the plant immune system in N. benthamiana were assessed by qPCR. The expression of endochitinase B and PI1 (proteinase inhibitor 1) genes showed a significant induction at 2 dpi and 3 dpi, respectively (Fig. 4). The two transcription factors ERF1 (ethylene response factor 1) and WRKY12 were also strongly induced at 1 dpi and 2 dpi, respectively (Fig. 4). However, for both transcription regulators, the gene expression decreased at 3 dpi to a level comparable to the control (Fig. 4). Among the selected pathogenicity related (PR) proteins, only PR3 and PR4a were induced at 3 dpi compared to the control (Fig. 4). PR1a, PR2, and PR5 did not show any significant transcriptional change when compared to the control during the 3-day time course of the experiment (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Gene expression levels of several markers related to plant immunity in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves transiently expressing HaSSP30 for 1, 2, and 3 days. Nicotiana benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 carrying either the pICH86988-empty (Control) or pICH86988-HaSSP30 (HaSSP30) vector. The plants were incubated in a plant growth room with 12 h/12 h, night/day photoperiods at 20–24 °C with 60% relative humidity (RH). The leaves were harvested after 1, 2, and 3 days post-infiltration (dpi). Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed into cDNA. The qPCR was performed on the cDNA using specific primers for several genes related to activation of plant immunity. Two reference genes were used to normalize the data, which are presented as normalized relative quantities scaled to control. Error bars indicated the standard deviation (SD) of 3 independent replicates (n = 3). Two-tailed Student t-test was used to compare HaSSP30 versus Control in each day and p-values < 0.05 are indicated above the bars.

Discussion

H. annosum is considered one of the most destructive necrotrophic pathogens of conifers in the northern hemisphere1. To date, there is very little information available about the pathogenicity factors that enable this fungus to actively attack and colonize the host. Moreover, there are no data currently available regarding small secreted protein (HaSSP)-encoding genes, which may be important for the fungal virulence. Our approach was aimed to identify candidate HaSSPs that function specifically during the necrotrophic fungus growth stage. Most of the studies about necrotrophic small secreted protein encoding genes are related to crop pathogens, in particular, S. nodorum and P. tritici-repentis 22–24. Additionally, there is basically no information available for necrotrophic forest fungal pathogens, with the exception of the hemibiotroph pine pathogen Dothistroma septosporum 19, 25. By applying a bioinformatics pipeline approach, we selected 58 putative small secreted protein encoding genes from the H. annosum TC 32-1 genome (Table 1). All the selected proteins were presumably capable of being secreted and did not contain any predicted protein domains. The selected HaSSPs are relatively small (Fig. 1), contain disulfide bridges which stabilize the protein structure, and are species-specific with no orthologues in other species8. The GEO database contains gene expression data for only 52 HaSSPs out of the 58 selected in this study (Fig. 2). The microarray oligonucleotide probes were selected using the first version of the H. annosum TC 32-1 genome annotation (v1.0), while in this study, the HaSSP-encoding genes were selected from the latest genome annotation (v2.0). The missing transcriptomic data for 6 HaSSP-encoding genes in the microarrays can be explained by the differences between the two versions of the genome annotation. However, most of the HaSSP-encoding genes show a high transcript level, indicating that they represent genuine genes that are actively transcribed in H. annosum. The 2 conditions related to the necrotrophic growth of H. annosum in the pine phloem and xylem form a distinct cluster within the samples. This probably indicates that most of the HaSSP-encoding genes are differentially regulated during the necrotrophic fungal infection compared to the other conditions, which mainly correspond to a saprotrophic lifestyle and growth in liquid media (Fig. 2).

The 58 genes were then synthesized to expedite the screening process and to optimize the codon usage for the Golden Gate cloning approach26. Due to the lack of a suitable transformation system in H. annosum and to the technical limitations of using mature pine trees for functional gene studies, we selected the well-established N. benthamiana/Agrobacterium system to assess the effect of the 58 H. annosum HaSSP-encoding genes. N. benthamiana has been extensively studied as a model system for elucidating the function and localization of fungal effectors by agroinfiltration27, 28. In our study, we found that 8 of the 58 selected HaSSPs from the H. annosum genome were able to induce chlorotic lesions and cell death when transiently expressed in N. benthamiana (Fig. 3). In a recent study of the rust poplar pathogen Melampsora larici-populina, while showing clear subcellular localization of fungal effectors, the authors did not report the induction of plant cell death27. However, recent studies investigating the function of selected effectors of the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici and the rice smut pathogen Ustilaginoidea virens reported the triggering of plant cell death when these effectors were transiently expressed in the non-host N. benthamiana 29, 30. Although H. annosum has not been previously shown to infect and colonize N. benthamiana, we identified 8 HaSSPs that could reproducibly trigger plant cell death. A similar result, both in the number of positive candidates and in the experimental methods, has been achieved for the wheat pathogen Z. tritici, for which 14 out of 63 candidate effectors tested were able to induce cell death in the non-host N. benthamiana 29. While most of the positive candidates could induce a certain level of chlorosis within 3 to 6 dpi, 2 HaSSPs (HaSSP30 and HaSSP47) could strongly induce plant cell death at 2 dpi (Fig. 3). A more detailed sequence comparison between the HaSSP30 and HaSSP47 protein sequences revealed that they are indeed two different isoforms of the same protein (HaSSP47 includes an additional 45 amino acids in its C-terminal domain, Supplementary Fig. S3). This further serves as an internal control that supports the hypothesis that HaSSP30 is a prime candidate for future functional studies.

We investigated the ability of HaSSP30 to induce the activation of the N. benthamiana immune system by assessing the gene expression of selected pathogenesis-related genes (PR) and markers for the hypersensitive response (HR). HaSSP30 could induce several Nicotiana chitinase genes (PR3, PR4a, and endochitinase B) at 2 to 3 dpi compared to the control. In contrast, other pathogenesis-related genes (PR1a, PR2, and PR5) did not show any variation in their transcript level compared to the control. The induction of genes belonging to the PR1 and PR2 class was shown to require the plant hormone salicylic acid, which controls the response to biotrophic pathogens31. On the other hand, the induction of genes of the PR3 and PR4 class is stimulated by jasmonic acid, which triggers the response to necrotrophic pathogens31, 32. Since H. annosum is a necrotrophic pathogen, our data suggested that the HaSSP30 protein may act as a necrotrophic effector that triggers a necrotrophic-specific response in plant cells. In an earlier study, we revealed that the defence mechanism against H. annosum s.l. in Norway spruce may involve jasmonate-dependent, salicylate-independent signalling33. The robust induction of the transcription regulator ERF1 provides further support for the role of HaSSp30 as a potential necrotrophic effector of Nicotiana (Fig. 4). ERF1 acts as a key player in the crosstalk between the plant hormone ethylene and jasmonate signalling by regulating the expression of defence-related genes34. In the plant model system Arabidopsis thaliana, the transcription of ERF1 was shown to be synergistically activated by both ethylene and jasmonate signalling pathways, which are required for the plant immune response against necrotrophic pathogens34, 35. Two other markers for plant cell death, the protease inhibitor PI1 and transcription regulator WRKY12, were also strongly induced in the Nicotiana leaves transiently expressing HaSSP30. The strong induction of PI1 in our study confirmed that the observed symptoms are indeed related to plant cell death, since plant protein inhibitors have been shown to be implicated in defence against pathogens and programmed cell death36. On the other hand, WRKY12 is a transcription regulator that has been implicated in the defence against soft rot disease caused by the necrotroph Pectobacterium carotovorum in both Arabidopsis and Chinese cabbage37. WRKY12 overexpression reduced the disease symptoms and increased the expression of defence genes in Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis, including PR4, which was also induced in our study37. Several WRKY transcriptional regulators have been shown to be important for resistance against necrotrophic pathogens. For example, the Arabidopsis WRKY33 mutation induced increased susceptibility to the necrotrophs Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria brassicicola 38. In conclusion, the transient expression in N. benthamiana of HaSSP30 alone can trigger a transcriptional response, which is consistent with previous reports of necrotrophic pathogens.

In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of the use of the N. benthamiana agroinfiltration system to identify putative effector-like proteins from the conifer necrotrophic pathogen H. annosum. Although Heterobasidion has not been previously shown to infect Nicotiana plants, our results revealed that transient expression of certain predicted HaSSPs in this system could induce plant cell death. The mechanism of action is still unclear, especially with regard to the hypothetical protein HaSSP30. However, we hypothesize that similar activation pathways for the host immune system may be conserved between Nicotiana and conifers. In this case, HaSSP30 could potentially interact with its Nicotiana orthologues and, consequently, trigger cell death. The identification of the specific plant receptors that interact with the cell death-inducing HaSSP30 will be the next research priority. The elucidation of the mechanism of action of HaSSP30 in Nicotiana will shed light on the H. annosum infection mechanisms in natural conifer hosts.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial, fungal strains and growth conditions

Escherichia coli TOP10F (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Finland) was used for gene cloning and plasmid propagation. Expression plasmids were introduced in Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 competent cells by cold shock protocol. Nicotiana benthamiana was used for the transient gene expression and quantitative PCR (qPCR) experiments. The plants were grown at 12 h/12 h, night/day photoperiods at 20–24 °C with 60% relative humidity.

Selection of the candidate small secreted protein (HaSSPs) encoding genes

The sequenced genome of H. annosum TC32-1, available in Mycocosm39 at the JGI portal (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/Hetan2/Hetan2.home.html, v2.0 June 2010), was used to identify the putative small secreted protein (HaSSP) encoding genes investigated in this study21. The pipeline used is a modified version of the one previously described40. Briefly, the PexFinder program41, 42 was used to identify all the proteins with signal peptides from the list of all predicted proteins in the H. annosum TC 32-1 genome. The list was then condensed by removing transmembrane, mitochondrial, and nuclear proteins using TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/), TargetP43, and PredictNLS44. Additionally, proteins with a predicted InterPro domain and wood-degrading enzymes were removed in order to focus only on novel and uncharacterized HaSSPs. Finally, we predicted disulfide bridges, which are thought to stabilize the protein structure, using DiANNA45.

Analysis of the expression levels of the candidate H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSP) encoding genes from microarray data

Transcriptomic data related to several fungal growth conditions were used to verify the expression levels of the candidate HaSSPs. The H. annosum transcriptomic data were retrieved from the public GEO database46. The dataset contains the transcriptional response of H. annosum grown under different conditions: necrotrophic growth in pine, saprotrophic growth on wood material and soil, and growth in various liquid media. The details of the experimental conditions, RNA extraction, and microarray hybridization were as previously described21, 47. Data GEO accession numbers, description of the samples, and reference to the publications are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

The microarray raw data were imported in R48, and the oligo package49 was used to normalize and extract the microarray expression values for the selected HaSSPs. For each gene, the mean value for the all biological replicates was calculated to have one single transcriptional profile for each condition. The cluster analysis was performed with the gplots package using the Euclidean distance to calculate the distance matrix and the average method for the agglomeration clustering50. Finally, the statistic p-values for the sample and gene clusters were calculated in R using the pvclust package to assess the statistical significance of the cluster analysis51.

Cloning of the candidate H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSP) encoding genes

The genes encoding the selected candidate H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSP) were custom synthesized (GeneWiz, UK). Briefly, the restriction sites for the type II enzymes BpiI and BsaI were removed from the gene coding sequence by codon optimization (GeneWiz, UK). The nucleotide sequences were designed to include BpiI restriction sites at both termini (5′-CACCGAAGACACAATG/TAAGCTTCCGTCTTCGTAG-3′) and cloned into pUC57 plasmid. The HaSSP coding sequences were then cloned by the Golden Gate approach into the Level0 pICH41308 plasmid (Addgene, UK)26, 52 using BpiI (NEB, Finland). From Level0 plasmids, the HaSSP coding sequences were cloned into the expression vector, Level2 pICH86988, creating the final vector pICH86988-HaSSP (35 S promoter and octopine synthase terminator, Addgene, UK) using the BsaI restriction enzyme (NEB, Finland). All cloning procedures were performed using the Golden Gate approach (for details about Golden Gate cloning visit http://synbio.tsl.ac.uk/golden-gate/) and E. coli TOP10F for selection of positive transformants.

Transient expression of the candidate H. annosum small secreted protein (HaSSPs) encoding genes in Nicotiana benthamiana

The pICH86988-HaSSP vector was transferred to A. tumefaciens GV3101 by the cold-shock transformation method. The bacteria were selected on LB solid media containing gentamicin (100 µg/ml), rifampicin (10 µg/ml), tetracycline (3 µg/ml), and kanamycin (50 µg/ml). For agroinfiltration in N. benthamiana, the A. tumefaciens carrying the selected construct to be expressed was grown in 3 ml liquid LB media supplemented with gentamicin (100 µg/ml), rifampicin (10 µg/ml), tetracycline (1.5 µg/ml), and kanamycin (20 µg/ml) overnight at 28 °C under shaking. The day after, 10–20 µl of the LB culture were inoculated into 10 ml YEB medium (5 g/l beef extract, 1 g/l yeast extract, 5 g/l bacteriological peptone, 5 g/l sucrose, and 2 ml of 1 M MgSO4) containing gentamicin (100 µg/ml), rifampicin (10 µg/ml), tetracycline (1.5 µg/ml), kanamycin (20 µg/m), 2 μM acetosyringone, and 10 mM MES. The cultures were grown overnight at 28 °C and 200 rpm to an OD600 = 1. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (1500 g for 5 min) and resuspended in 5 ml MMA infiltration medium (5 g/l MS salts, 1.95 g/l MES (2-[N-Morpholino] ethane sulfonic acid), 20 g/l sucrose, pH = 5.6) supplemented with 200 μM acetosyringone. The bacterial liquid culture was finally adjusted to OD600 = 0.3 with MMA infiltration medium and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 2 h. N. benthamiana leaves were agroinfiltrated with the A. tumefaciens carrying the selected pICH86988-HaSSP and incubated until symptoms developed in 2 to 6 days.

Assessment of the expression levels of plant immune response-related genes in Nicotiana benthamiana infiltrated with the HaSSP30 gene

N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens carrying either pICH86988-empty (Control) or pICH86988-HaSSP30 (HaSSP30) with 3 biological replicates each. Total RNA was extracted after 1, 2, and 3 days post infiltration (dpi) using TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Finland) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was reverse transcribed as follows: 1 µg RNA was treated with DNase I (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Finland) at 37 °C for 30 min followed by enzyme inactivation by adding 1 µl EDTA 50 mM at 65 °C for 10 min in 11 µl total volume. One microliter of random hexamer primers (100 µM) and 0.5 µl nuclease free water were added to the DNase treated RNA; the reaction was incubated at 65 °C for 5 min and then cooled on ice. The following components were then added to the reaction mixture: 2 µl dNTPs (10 mM), 0.5 µl RiboLock RNase Inhibitor, 4 µl 5X RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase buffer, and 1 µl RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (200 U/µl) (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Finland). The RNA was reverse transcribed by incubating the reaction mixture for 10 min at 25 °C and then for 60 min at 42 °C. The reaction was finally incubated at 70 °C for 5 min. The final volume was 20 µl.

Nine markers for the plant immune system (Endochitinase B, ERF1a, PI1, PR1a, PR2, PR3, PR4a, PR5, and WRKY12) and 2 reference genes (EF1a and Actin) were assessed by qPCR. The qPCR reaction mixture was assembled with 5.5 µl cDNA template (1:15 dilution), 1 µl forward primer, 1 µl reverse primer, and 7.5 µl 2X LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche, Finland). The 384-well plates were analysed via a LightCycler 480 II (Roche, Finland) with the following program: preincubation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 45 amplification cycles (95 °C for 10 sec, 60 °C for 10 sec, and 72 °C for 10 sec). Following cycle completion, samples were subjected to melting curve analysis to assess the primer specificity. The qPCR data were analysed in R48 using the EasyqpcR package53 and normalized using 2 reference genes (EF1a and Actin). Primer information is summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Academy of Finland (project no. 276862). We also thank Dr. Benjamin Petre and Prof. Sophien Kamoun (The Sainsbury Laboratory, Norwich, UK) for assistance with the cloning design and for further verification and validation of HaSSP30. We gratefully acknowledge the Heterobasidion Genome Consortium for access to the published data.

Author Contributions

F.O.A. and T.R. conceived the study. T.R. planned and performed the experiments, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. F.O.A. revised and edited the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08010-0

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Asiegbu FO, Adomas A, Stenlid J. Conifer root and butt rot caused by Heterobasidion annosum (Fr.) Bref. s.l. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2005;6:395–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otrosina WJ, Garbelotto M. Heterobasidion occidentale sp nov and Heterobasidion irregulare nom. nov.: A disposition of North American Heterobasidion biological species. Fungal Biology. 2010;114:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niemela, T. & Korhonen, K. Taxonomy of the genus Heterobasidion (C A B International, 1998).

- 4.Woodward, S., Stenlid, J., Karjalainen, R. & Hüttermann, A. Heterobasidion annosum: biology, ecology, impact and control (Cab International, 1998).

- 5.Redfern, D. B. & Stenlid, J. Spore dispersal and infection. Heterobasidion Annosum: Biology, Ecology, Impact and Control 105–124 (1998).

- 6.Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickman MB, Fluhr R. Centrality of host cell death in plant-microbe interactions. Annual Review of Phytopathology, Vol 51. 2013;51:543–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo Presti L, et al. Fungal effectors and plant susceptibility. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2015;66(66):513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-114623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean RA, et al. The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature. 2005;434:980–986. doi: 10.1038/nature03449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jonge R, et al. Conserved fungal LysM effector Ecp6 prevents chitin-triggered immunity in plants. Science. 2010;329:953–955. doi: 10.1126/science.1190859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Esse HP, Bolton MD, Stergiopoulos I, de Wit PJGM, Thomma BPHJ. The chitin-binding Cladosporium fulvum effector protein Avr4 is a virulence factor. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2007;20:1092–1101. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-9-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mentlak TA, et al. Effector-mediated suppression of chitin-triggered immunity by Magnaporthe oryzae is necessary for rice blast disease. Plant Cell. 2012;24:322–335. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.092957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller, A. N., Ziemann, S., Treitschke, S., Assmann, D. & Doehlemann, G. Compatibility in the Ustilago maydis-maize interaction requires inhibition of host cysteine proteases by the fungal effector Pit2. Plos Pathog9, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003177 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.van Esse HP, et al. The Cladosporium fulvum virulence protein Avr2 inhibits host proteases required for basal defense. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1948–1963. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubicek CP, Starr TL, Glass NL. Plant cell wall-degrading enzymes and their secretion in plant-pathogenic fungi. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 2014;52(52):427–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-045831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stergiopoulos I, Collemare J, Mehrabi R, De Wit PJGM. Phytotoxic secondary metabolites and peptides produced by plant pathogenic Dothideomycete fungi. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2013;37:67–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friesen TL, Faris JD, Solomon PS, Oliver RP. Host-specific toxins: effectors of necrotrophic pathogenicity. Cellular microbiology. 2008;10:1421–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciuffetti LM, Tuori RP, Gaventa JM. A single gene encodes a selective toxin causal to the development of tan spot of wheat. Plant Cell. 1997;9:135–144. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradshaw RE, et al. Genome-wide gene expression dynamics of the fungal pathogen Dothistroma septosporum throughout its infection cycle of the gymnosperm host Pinus radiata. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2016;17:210–224. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mesarich CH, et al. A conserved proline residue in Dothideomycete Avr4 effector proteins is required to trigger a Cf-4-dependent hypersensitive response. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2016;17:84–95. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson A, et al. Insight into trade-off between wood decay and parasitism from the genome of a fungal forest pathogen. New Phytologist. 2012;194:1001–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan, K. C. et al. Functional redundancy of necrotrophic effectors - consequences for exploitation for breeding. Front Plant Sci6, doi:10.3389/Fpls.2015.00501 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Liu, Z. H. et al. The cysteine rich necrotrophic effector SnTox1 produced by Stagonospora nodorum triggers susceptibility of wheat lines harboring Snn1. Plos Pathog8, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002467 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Abeysekara NS, Friesen TL, Keller B, Faris JD. Identification and characterization of a novel host-toxin interaction in the wheat-Stagonospora nodorum pathosystem. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;120:117–126. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Wit, P. J. G. M. et al. The genomes of the fungal plant pathogens Cladosporium fulvum and Dothistroma septosporum reveal adaptation to different hosts and lifestyles but also signatures of common ancestry. PLoS genetics8, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003088 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Weber, E., Engler, C., Gruetzner, R., Werner, S. & Marillonnet, S. A modular cloning system for standardized assembly of multigene constructs. PloS one6, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016765 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Petre B, et al. Candidate effector proteins of the rust pathogen Melampsora larici-populina target diverse plant cell compartments. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2015;28:689–700. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-15-0003-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Win J, Kamoun S, Jones AME. Purification of effector-target protein complexes via transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Immunity: Methods and Protocols. 2011;712:181–194. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-998-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kettles GJ, Bayon C, Canning G, Rudd JJ, Kanyuka K. Apoplastic recognition of multiple candidate effectors from the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici in the nonhost plant Nicotiana benthamiana. The New phytologist. 2017;213:338–350. doi: 10.1111/nph.14215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang AF, et al. Identification and characterization of plant cell death-inducing secreted proteins from Ustilaginoidea virens. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2016;29:405–416. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-15-0200-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomma BPHJ, et al. Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense-response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct microbial pathogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:15107–15111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spoel SH, Dong XN. How do plants achieve immunity? Defence without specialized immune cells. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2012;12:89–100. doi: 10.1038/nri3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnerup J, et al. The primary module in Norway spruce defence signalling against H. annosum s.l. seems to be jasmonate-mediated signalling without antagonism of salicylate-mediated signalling. Planta. 2013;237:1037–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1822-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenzo O, Piqueras R, Sanchez-Serrano JJ, Solano R. Ethylene Response Factor1 integrates signals from ethylene and jasmonate pathways in plant defense. Plant Cell. 2003;15:165–178. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berrocal-Lobo M, Molina A, Solano R. Constitutive expression of Ethylene-response-factor1. Arabidopsis confers resistance to several necrotrophic fungi. Plant Journal. 2002;29:23–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haq SK, Atif SM, Khan RH. Protein proteinase inhibitor genes in combat against insects, pests, and pathogens: natural and engineered phytoprotection. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2004;431:145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HS, et al. Overexpression of the Brassica rapa transcription factor WRKY12 results in reduced soft rot symptoms caused by Pectobacterium carotovorum in Arabidopsis and Chinese cabbage. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 2014;16:973–981. doi: 10.1111/plb.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng ZY, Abu Qamar S, Chen ZX, Mengiste T. Arabidopsis WRKY33 transcription factor is required for resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. Plant Journal. 2006;48:592–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grigoriev IV, et al. The genome portal of the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D26–32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saunders, D. G. O. et al. Using hierarchical clustering of secreted protein families to classify and rank candidate effectors of rust fungi. PloS one7, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029847 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Torto TA, et al. EST mining and functional expression assays identify extracellular effector proteins from the plant pathogen Phytophthora. Genome research. 2003;13:1675–1685. doi: 10.1101/gr.910003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, vonHeijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. Journal of molecular biology. 2000;300:1005–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nair R, Rost B. Better prediction of sub-cellular localization by combining evolutionary and structural information. Proteins. 2003;53:917–930. doi: 10.1002/prot.10507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferre F, Clote P. DiANNA: a web server for disulfide connectivity prediction. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:W230–W232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barrett T, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets-update. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raffaello, T., Chen, H., Kohler, A. & Asiegbu, F. O. Transcriptomic profiles of Heterobasidion annosum under abiotic stresses and during saprotrophic growth in bark, sapwood and heartwood. Environmental microbiology, doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12321 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2013).

- 49.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2363–2367. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting data (2014).

- 51.Suzuki R, Shimodaira H. Pvclust: an R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1540–1542. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Engler, C., Kandzia, R. & Marillonnet, S. A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PloS one3, doi:10.1371/Journal.Pone.0003647 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.EasyqpcR: EasyqpcR for easy analysis of real-time PCR data (IRTOMIT-INSERM U1082, 2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.