Abstract

Variceal bleeding is one of the major causes of death in cirrhotic patients. The management during the acute phase and the secondary prophylaxis is well defined. Recent recommendations (2015 Baveno VI expert consensus) are available and should be followed for an optimal management, which must be performed as an emergency in a liver or general intensive-care unit. It is based on the early administration of a vasoactive drug (before endoscopy), an antibiotic prophylaxis and a restrictive transfusion strategy (hemoglobin target of 7 g/dL). The endoscopic treatment is based on band ligations. Sclerotherapy should be abandoned. In the most severe patients (Child Pugh C or B with active bleeding during initial endoscopy), transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) should be performed within 72 hours after admission to minimize the risk of rebleeding. Secondary prophylaxis is based on the association of non-selective beta-blockers (NSBBs) and repeated band ligations. TIPS should be considered when bleeding reoccurs in spite of a well-conducted secondary prophylaxis or when NSBBs are poorly tolerated. It should also be considered when bleeding is refractory. Liver transplantation should be discussed when bleeding is not controlled after TIPS insertion and in all cases when liver function is deteriorated.

Keywords: variceal bleeding, cirrhosis, endoscopic treatment, non-selective beta-blockers, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, liver transplantation

Introduction

Acute variceal bleeding is one of the major causes of death in cirrhotic patients [1]. It is also the major cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in cirrhotic patients, accounting for 70% of cases [2]. Mortality during the first episode is estimated to 15–20% [3], but is higher in severe patients (Child Pugh C), at around 30%, whereas it is very low in patients with compensated cirrhosis (Child Pugh A) [3]. The main predictors of bleeding in clinical practice are: large versus small varices, red wale marks, Child Pugh C versus Child Pugh A–B [4].

In recent years, significant improvements have been made regarding the management of acute variceal bleeding, leading to a better prognosis [5,6]. Recent recommendations (2015 Baveno VI expert consensus) summarize the most important aspects [6]. In this review, we will discuss Baveno VI conclusions and more recent data in order to provide guidance for an optimal management of variceal bleeding.

Management of acute bleeding

Unspecific measures

Resuscitation

Restoring mean arterial pressure (MAP) allowing an adequate tissue perfusion is of major importance. Prolonged hypovolemia favors kidney failure and bacterial infections, and increases mortality [7]. Conversely, portal pressure follows a linear correlation with MAP. As such, excessive MAP could promote bleeding [8,9]. The optimal MAP is not well defined in this context, but a target of around 65 mmHg can reasonably be extrapolated from recommendations established for septic or hemorrhagic shock in trauma patients [10,11]. Transfusion of packed red blood cells should be performed with a restrictive hemoglobin target of 7 g/dL [6,12]. A liberal transfusion strategy (hemoglobin target of 9 g/dL) has been associated with a poorer prognosis in Child Pugh A and B patients. This effect was not observed in the most severe patients (Child Pugh C), either because of a lack of power of the study or because of a more severe hypovolemia in these patients [12]. Transfusion strategy should be adapted to specific situations such as high cardiovascular risk. The effect of fresh frozen plasma administration has never been evaluated during variceal bleeding and no recommendations are available. It is important to note that prothrombin rate and international normalized ratio (INR) should be considered as markers of liver function and not of coagulation disorders [13]. Correcting them is not part of the management of variceal bleeding. Platelet transfusion is usually recommended when platelet count falls below 30 000/mm6. No specific data are available for variceal bleeding patients. Two studies have evaluated the effect of recombinant factor VII administration during variceal bleeding [14,15]. No significant results have been obtained. A potential efficacy in the subgroup of patients with severe cirrhosis (Child Pugh C) with active bleeding was noted in the post-hoc analyses. This therapeutic is not recommended.

Prior to endoscopy

In the absence of contraindications (QT prolongation), infusion of erythromycin 250 mg as a prokinetic agent should be administered in order to improve stomach clearance and thus facilitate endoscopy [6]. Gastric lavage has shown no superiority compared to erythromycin or both therapeutics [16].

Proton pump inhibitors (PPI)

It is not recommended to use PPI during variceal bleeding. A randomized trial has studied the effect of PPI administration after endoscopic band ligation (EBL) [17]. The size of post-banding ulcers was smaller in the PPI group but their number and clinical repercussions were similar. In addition, there are more and more data showing that the use of PPI in cirrhotic patients favors bacterial infections including spontaneous peritonitis [18,19]. Initiation of PPI before endoscopy is debated but commonly practiced in cirrhotic patients. It has been proven to facilitate endoscopy in ulcer bleedings in a large prospective cohort study [20]. Whether this strategy is effective in cirrhotic patients is uncertain, as only 5% of the patients included in this study were cirrhotic. In any case, high-dose PPI should be discontinued when ulcer is ruled out.

Specific measures

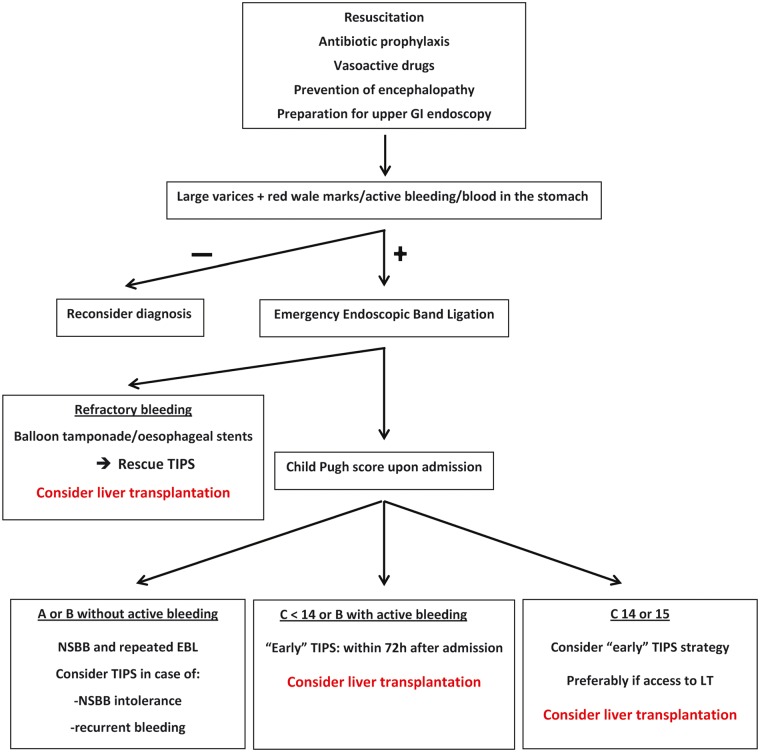

The management of variceal bleeding associates vasoactive drugs, antibiotic prophylaxis and EBL [6]. An algorithm for the use of specific measures is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the management of acute variceal bleeding.

Vasoactive drugs

Three types of drugs are available: somatostatin, somatostatin analogs such as octreotide, and terlipressin. All these drugs induce splanchnic vasoconstriction and reduce portal pressure. The choice depends on availability, cost and contraindications. Somatostatin has an effect on splanchnic hemodynamic through splanchnic arterial vasoconstriction, leading to a decrease in portal pressure (reflected by wedged hepatic pressure) [21,22]. This effect has been shown during variceal bleeding [23,24]. Somatostatin, administered early before endoscopy, tested against placebo, has led to fewer cases of active bleeding during endoscopy and fewer hemorrhagic recurrences [25]. In practice, somatostatin or octreotide should be administered as early as possible with bolus infusion of 250 µg and 50 µg followed by continuous infusion of 250 µg/h and 50 µg/h, respectively [26,27]. Terlipressin is a vasopressin analog. It is an arterial vasoconstrictor with splanchnic and general effect. It should not be used in high-cardiovascular-risk patients. Early administration of terlipressin against placebo during variceal bleeding has led to an improved survival [28,29]. Recently, a randomized trial including more than 1000 patients has compared the administration of somatostatin, terlipressin or octreotide after EBL and antibiotic prophylaxis [30]. Efficacy (hemorrhage control at Day 5) was similar in the three groups. More adverse effects were observed in the terlipressin group, especially hyponatremia, which should be monitored in case of terlipressin use. In practice, there is no recommendation on which drug to use and the first available should be preferred.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Without antibiotic prophylaxis, 30–40% of cirrhotic patients presenting with upper GI bleeding will develop a bacterial infection within 1 week after admission [31]. These infections originate from bacterial translocation towards mesenteric lymph nodes, blood stream and potentially ascites. Translocation is facilitated by GI bacterial overgrowth, higher intestinal barrier permeability and altered immunity during cirrhosis. Most infections are due to gram-negative bacteria. Anaerobic bacteria are rarely isolated. Cirrhotic patients with all causes of upper GI bleeding (directly related to portal hypertension or not) are concerned. Infections are associated with a higher rate of early rebleeding and a higher mortality [31–34]. The risk of infection rises with the severity of cirrhosis [35]. A systematic antibiotic prophylaxis during upper GI bleeding leads to fewer infections and a lower short-term mortality, which seems to be the consequence of a lower rate of early rebleeding [32–36]. For these reasons, antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for 7 days in all cirrhotic patients admitted for upper GI bleeding [6]. Oral norfloxacin, 400 mg twice daily, can be used because of its activity against gram-negative bacteria and its weak intestinal absorption. Other quinolones, such as ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin, can also be used when the oral route is impossible, as well as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid or third-generation cephalosporins.

Gram-negative bacteria resistance to quinolones is a rising concern and the use of quinolones has been challenged. A study has compared antibiotic prophylaxis with IV ceftriaxone or oral norfloxacin in severe patients (Child Pugh B or C). The use of ceftriaxone was associated with a lower rate of suspected or proven infections [37]. The authors attributed the results to the high rate of quinolone-resistant bacteria. Nevertheless, this conclusion must be balanced, for two reasons. The rate of quinolone-resistant bacteria in the hospital where the study was performed was unknown. Infections were also more frequent in the quinolone group than in most studies previously published. Baveno VI’s recommendations state that IV ceftriaxone should be considered in patients with advanced cirrhosis, in hospital settings with a high prevalence of quinolone-resistant bacteria or in patients with previous quinolone prophylaxis. Recently, in Child Pugh A patients only, a non-randomized study showed that infections occurred at a similar frequency (1% vs 2%) with or without antibiotic prophylaxis [35]. The advantage of antibiotic prophylaxis in these patients is thus a matter of debate, especially at a time when use of antibiotics should be cautious due to the spread of multi-resistant bacteria. Further randomized studies will address this question and eventually lead to avoidance of antibiotic prophylaxis in Child Pugh A patients.

Endoscopic treatment

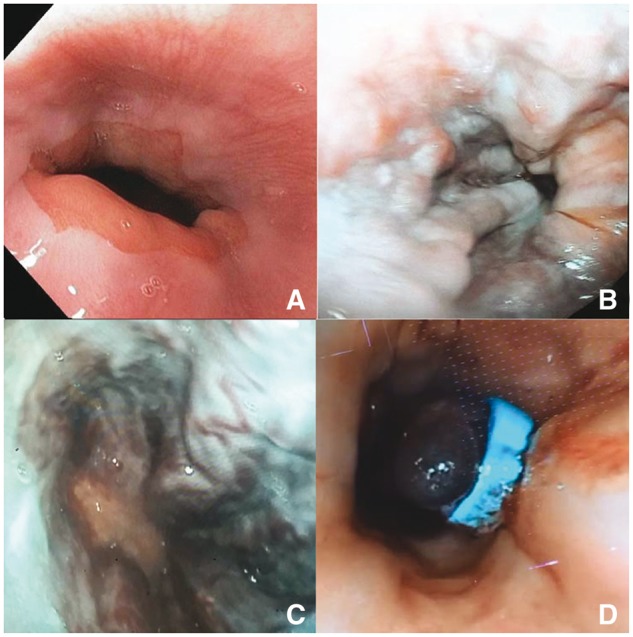

Endoscopic diagnosis of variceal bleeding relies on the presence of large varices and red wale marks or active bleeding. The presence of blood in the stomach without any other cause but large varices is also possible. It is recommended to perform upper GI endoscopy as soon as possible (within 12 hours) after initial resuscitation [6]. Endoscopy should be performed by an endoscopist and a support staff proficient in endoscopic hemostasis techniques [6]. Airways should be protected in patients with altered consciousness. Furthermore, Baveno VI’s recommendations state that acute variceal bleeding patients should be managed in an intensive-care or well-monitored unit. Sclerotherapy is the oldest endoscopic treatment for variceal bleeding. Due to almost constant formation of an ulcer on the site of injection, sometimes responsible for a hemorrhage, sclerotherapy should be abandoned. EBL, the actual treatment of choice, should be performed during initial endoscopy [38] (Figure 2). Minor complications can occur such as dysphagia or chest pain. Post-banding ulcer bleeding can occur around Day 7 and be clinically significant. EBL has never been compared to the absence of endoscopic treatment. However, it has been compared to sclerotherapy in several studies, all in favor of less rebleeding and fewer side effects when performing EBL [39–41].

Figure 2.

Endoscopic band ligation. (A) Normal esophagus. (B) and (C) Large esophageal varices with red wale marks. (D) Post-banding necrosis of varicose tissue.

Balloon tamponade and self-expending metal stent (SEMS)

Balloon tamponade through a nasogastric tube equipped with inflatable balloons (esophagus and stomach), usually named Blakemore’s tube, is effective to control variceal bleeding [42,43]. It is associated with severe complications such as necrosis or perforation of the esophagus and aspiration pneumonia. Endotracheal intubation to protect airways is thus necessary. Hemorrhage recurrence occurs in more than 50% of cases after deflation. It is thus only a temporary solution when bleeding is not controlled. Recently, esophageal SEMS have been developed to replace Blakemore’s tube [44]. They offer the advantages of allowing oral intakes after the acute phase and being removable. A recent randomized controlled trial comparing SEMS and balloon tamponade during refractory variceal bleeding showed a better control of bleeding and fewer adverse events when using esophageal stents [45]. Survival was better, but not significantly. Baveno VI’s recommendations state that esophageal stenting should be preferred to balloon tamponade.

Emergency portosystemic shunts

Surgical portosystemic anastomoses, once the rescue treatment for refractory variceal bleeding, have been almost abandoned. Nowadays, intrahepatic shunting though transjugular insertion of a stent, commonly named a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), is the treatment of choice for refractory variceal bleeding as well as for secondary prophylaxis in severe patient, as we will further develop. TIPS insertion during refractory variceal bleeding, also called salvage TIPS, is effective to control bleeding in almost all cases [46]. Nevertheless, mortality after 1 year remains high (around 50%), even since the use of covered stents, with a low risk of thrombosis leading to recurrence of portal hypertension. Elevated mortality is due to other complications of severe cirrhosis such as infections, kidney failure and encephalopathy. Salvage TIPS, eventually preceded by SEMS insertion [47], can however be a very attractive bridge to liver transplantation (LT). In our experience, making the decision of inserting a rescue TIPS should take into account the possibility of a LT in a near future [48].

Early TIPS placement for severe patients

TIPS were initially dedicated to the rescue treatment of refractory bleeding. There are now data suggesting that the most severe patients benefit from a systematic TIPS insertion after an initial bleeding episode, commonly named ‘early TIPS’ [49]. The pivotal study was published in the NEJM by García-Pagán et al. [50]. Child Pugh C < 14 or B with active bleeding at initial endoscopy were eligible. After initial management (vasoactive drugs and emergency EBL), there were randomized to receive combined therapy (non-selective beta-blockers [NSBBs] and EBL) or a covered TIPS within 3 days after initial bleed, after control of bleeding. Patients in the TIPS group were more often free from rebleeding (97% vs 50%) and had a higher 1-year survival (86% vs 61%). External validation studies confirmed the lower rebleeding rate but the benefit on survival is still a matter of debate [51]. A possible explanation is that patients in a study were highly selected (63 patients recruited over 3 years in nine centers), thus not fully comparable to those in validation studies. However, a recent meta-analysis was in favor of a benefit of survival [52]. Baveno VI’s recommendations state that TIPS must be considered in Child Pugh C or B with active bleeding at initial endoscopy. Availability of TIPS remains a practical issue. LT should rapidly be discussed in these patients, as the deterioration of liver function and occurrence of other complications of cirrhosis become at the forefront. Management of variceal bleeding in Child Pugh C 14 or 15 patients is still a matter of debate. These patients were excluded from the ‘early TIPS’ studies. In our experience, an ‘early TIPS’ strategy is a solution if the patient can have quick access to LT, as liver failure and encephalopathy are likely to keep deteriorating after TIPS [48].

Prevention of hepatic encephalopathy (HE)

Baveno VI’s recommendations do not include a specific strategy to prevent HE in the context of variceal bleeding. However, data from trials are now available. A prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) included 70 patients admitted for variceal bleeding with no signs of HE. Patients were allocated to receive lactulose or placebo [53]. The proportion of patients developing HE was significantly lower in the lactulose group (14% vs 40%, p = 0.03). Rifaximin is a non-absorbable antibiotic used in the prevention of recurrence of HE. Its efficiency to prevent HE in the context of variceal bleeding has been found to be similar to that of lactulose in a prospective RCT [54]. There were fewer digestive side effects with rifaximin.

Secondary prophylaxis

NSBBs and EBL

Due to a high risk of recurrent bleeding, it is essential to initiate a secondary prophylaxis after the first episode. EBL associated with NSBBs is the first-line strategy recommended [6]. The NSBB (propranolol and nadolol) effect consists of lowering portal pressure through a bradycardia that leads to a decrease in cardiac output (anti β1 action) and a splanchnic vasoconstriction (anti β2 action) [55]. Carvedilol, a potent alpha- and beta-blocker, has never been tested adequately in secondary prophylaxis. Its use is thus not recommended. Repeated EBL, usually every 2–4 weeks, leads to a disappearance of varices and reduces the risk of bleeding. A recent trial compared EBL sessions at an interval of 1 or 2 weeks [56]. Varices eradication was obtained quicker in the 1-week group, without additional complications. Nevertheless, the number of sessions needed, rebleeding rate and mortality were similar in both groups. Many studies have compared the use of NSBBs combined with EBL versus one of these treatments in a single therapy [57–59]. The results of a recent meta-analysis, combining the data of 23 trials, show a decrease in the risk of recurrent bleeding with a dual therapy, without any positive impact on survival [60]. However, survival was better in patients treated with NSBBs (single or combined therapy) compared to patients treated with EBL alone. Hence, EBL therapy alone should never be recommended and, if any contraindications to beta-blockers occur, TIPS should be discussed. Few severe patients (Child Pugh C) were included in these studies and it is uncertain whether the previous results are applicable to these patients.

NSBBs in patients with refractory ascites

Several studies have raised a concern about the safety of NSBBs in patients with ascites, as some papers claim a higher mortality in this subgroup when treated with NSBBs [61,62]. The detrimental effect of NSBBs appears to be more pronounced in patients who experienced an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) [62]. These results have been challenged by others studies that showed a survival benefit in patients with ascites treated with propranolol or carvedilol, even after adjustment for the severity of ascites or the occurrence of SBP [63,64]. Baveno VI’s guidelines recommend to use NSBBs with caution in patients with refractory ascites and to discontinue the treatment if poorly tolerated: systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, hyponatremia <130 mmol/L, episode of acute kidney injury. NSBBs can be restarted with titration if a precipitating factor for such an event has been identified and corrected. Baveno VI’s guidelines recommend TIPS insertion in secondary prophylaxis if NSBBs cannot be used.

TIPS in secondary prophylaxis

Extending the ‘early TIPS’ criteria after a variceal bleeding episode is a much debated issue. Until recently, studies were performed using bare stents, without any survival benefit of TIPS as first-line therapy in this setting. Baveno VI’s guidelines recommend TIPS if NSBBs cannot be used or if bleeding reoccurs in spite of a well-conducted combined therapy. Recently, two RCTs addressed this question, using covered TIPS [65,66]. They compared TIPS insertion versus a combined therapy in the first case [65] and used a tailored strategy starting initially with drugs alone in the second case [66]. Here, in the medical treatment group (no TIPS insertion), hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) was systematically measured before and after starting a combination of NSBBs and nitrates. Patients without hemodynamic response were switched to EBL only. In both studies, there was significantly less recurrence of bleeding in TIPS groups, but survival rates were similar, as well life-quality assessments. As well as in studies evaluating the effects of NSBBs and EBL, few Child Pugh C patients were included. Hence, TIPS should not be recommended at first-line therapy for secondary prophylaxis.

Hemodynamic response-guided prescription of NSBBs

Monitoring hemodynamic response to NSBBs is not recommended in Baveno VI consensus and poorly feasible in routine practice in most centers. However, short- and long-term hemodynamic responses to NSBBs (decrease of HVPG below 12 mmHg or more than 20% of baseline value) are associated with a lower risk of bleeding in primary or secondary prophylaxis [67,68]. In the setting of primary prophylaxis, carvedilol has been effectively used as a second-line treatment in non-responders to propranolol [69]. Recently, a RCT has validated a step-by-step increase in pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension guided with repeated HVPG measurements [70]. In the setting of secondary prophylaxis, nitrates and eventually prazosin (an alpha-blocker) were added to nadolol in cases of acute and chronic non-responders, respectively. Patients in the control group were treated with nadolol and nitrates from the beginning and the treatment was not modified in non-responders (measurements still performed). Mortality and rebleeding rates were lower in HVPG-guided-therapy patients alongside a deeper decrease in HVPG. It is worth noting that, in the Sauerbruch et al. study, the rebleeding rate was similar when comparing 8-mm TIPS and hemodynamic responders to NSBBs, highlighting the potential benefits of monitoring hemodynamic response to NSBBs [66].

Clinical benefit of statins in patients with variceal bleeding

Recently, Abraldes et al. demonstrated in a RCT that introducing simvastatin during an episode of variceal bleeding was associated with a better 1-year mortality, without improving the rate of rebleeding (in the setting of secondary prophylaxis with NSBBs and EBL) [71]. Child Pugh C patients did not take advantage of simvastatin prescription. The mechanisms underlying the benefit of statins in cirrhosis remain unclear, but their use is promising. Indeed, in a large Taiwanese retrospective cohort including hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV) and alcohol-related cirrhosis patients, it was shown that exposure to statins reduced the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and decompensation of cirrhosis [72].

Treatment of etiological factors

The treatment of the etiological factor(s) of cirrhosis is part of the management of complications of cirrhosis such as variceal bleeding. It has first been shown in cirrhosis related to chronic HBV that viral suppression with nucleoside analogs is efficient at reducing the risk of HCC and portal hypertension-associated complications including variceal bleeding [73–75]. Concerning HCV, direct-acting antiviral agents have recently led to high rates of sustained viral response (SVR). It has also been shown in HCV cirrhosis that achieving SVR was associated with a lower incidence of HCC and complications of portal hypertension [76]. Data are scarce in alcoholic cirrhosis but it is very likely that alcohol withdrawal has a positive effect on cirrhosis complications [77]. Patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) cirrhosis are also at risk of developing complications of cirrhosis [78]. Lifestyle intervention has been shown to improve histological lesions of NASH [79]. In the near future, it is likely that lifestyle and pharmacological interventions will also prove efficient in limiting the occurrence of complications of NASH cirrhosis.

Conclusion

The specific management of variceal bleeding is well codified: vasoactive drugs, antibiotic prophylaxis and EBL. For severe patients (Child Pugh C < 14 or B with active bleeding), a TIPS should be discussed in order to be placed within 72 hours. TIPS should also be inserted when hemorrhage reoccurs in spite of a well-conducted secondary prophylaxis. LT should be discussed in the rare cases when TIPS does not control bleeding and when liver function is deteriorated. However, some questions are still under debate: Which patients really take advantage of an ‘early TIPS’ strategy? How to improve TIPS availability? Should we routinely measure hemodynamic response to NSBBs? Is antibiotic prophylaxis necessary in Child Pugh A patients? Which patients really take advantage of statins prescription? Answering those questions will allow decreasing mortality, which remains high in cirrhotic patients presenting with variceal bleeding.

Conflict of interest statement: none declared.

Take home messages:

Variceal bleeding patients should be managed in emergency in an intensive care unit. A restrictive transfusion strategy should be applied.

Initial management always includes vasoactive drugs, antibiotic prophylaxis and emergency EBL.

Secondary prophylaxis depends on the severity of underlying cirrhosis. TIPS placement should be discussed in severe patients.

Liver transplantation should be discussed when liver function is deteriorated.

References

- 1. D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L.. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudler M, Rousseau G, Benosman H. et al. Peptic ulcer bleeding in patients with or without cirrhosis: different diseases but the same prognosis? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;36:166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carbonell N, Pauwels A, Serfaty L. et al. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology 2004;40:652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S. et al. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol 2003;38:266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haq I, Tripathi D.. Recent advances in the management of variceal bleeding. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017;5:113–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Franchis R; Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2015;63:743–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cardenas A, Gines P, Uriz J. et al. Renal failure after upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis: incidence, clinical course, predictive factors, and short-term prognosis. Hepatology 2001;34(4 Pt 1):671–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Castaneda B, Debernardi-Venon W, Bandi JC. et al. The role of portal pressure in the severity of bleeding in portal hypertensive rats. Hepatology 2000;31:581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Franchis R, Primignani M.. Natural history of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2001;5:645–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM. et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 2008;36:296–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rossaint R, Bouillon B, Cerny V. et al. ; Task Force for Advanced Bleeding Care in Trauma. Management of bleeding following major trauma: an updated European guideline. Crit Care 2010;14:R52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch J. et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2013;368:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li J, Qi X, Deng H. et al. Association of conventional haemostasis and coagulation tests with the risk of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis: a retrospective study. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2016;4:315–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bosch J, Thabut D, Bendtsen F. et al. Recombinant factor VIIa for upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized, double-blind trial. Gastroenterology 2004;127:815–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bosch J, Thabut D, Albillos A. et al. ; International Study Group on rFVIIa in UGI Hemorrhage. Recombinant factor VIIa for variceal bleeding in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology 2008;47:1604–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pateron D, Vicaut E, Debuc E. et al. ; HDUPE Collaborative Study Group. Erythromycin infusion or gastric lavage for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:582–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shaheen NJ, Stuart E, Schmitz SM. et al. Pantoprazole reduces the size of postbanding ulcers after variceal band ligation: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology 2005;41:588–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bajaj JS, Zadvornova Y, Heuman DM. et al. Association of proton pump inhibitor therapy with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1130–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trikudanathan G, Israel J, Cappa J. et al. Association between proton pump inhibitors and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2011;65:674–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lau JY, Leung WK, Wu JC. et al. Omeprazole before endoscopy in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1631–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bosch J, Kravetz D, Rodes J.. Effects of somatostatin on hepatic and systemic hemodynamics in patients with cirrhosis of the liver: comparison with vasopressin. Gastroenterology 1981;80:518–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cirera I, Feu F, Luca A. et al. Effects of bolus injections and continuous infusions of somatostatin and placebo in patients with cirrhosis: a double-blind hemodynamic investigation. Hepatology 1995;22:106–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Villanueva C, Ortiz J, Minana J. et al. Somatostatin treatment and risk stratification by continuous portal pressure monitoring during acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 2001;121:110–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Avgerinos A, Nevens F, Raptis S. et al. Early administration of somatostatin and efficacy of sclerotherapy in acute oesophageal variceal bleeds: the European Acute Bleeding Oesophageal Variceal Episodes (ABOVE) randomised trial. Lancet 1997;350:1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burroughs AK, McCormick PA, Hughes MD. et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of somatostatin for variceal bleeding: emergency control and prevention of early variceal rebleeding. Gastroenterology 1990;99:1388–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sung JJ, Chung SC, Yung MY. et al. Prospective randomised study of effect of octreotide on rebleeding from oesophageal varices after endoscopic ligation. Lancet 1995;346:1666–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Corley DA, Cello JP, Adkisson W. et al. Octreotide for acute esophageal variceal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2001;120:946–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Escorsell A, Bandi JC, Moitinho E. et al. Time profile of the haemodynamic effects of terlipressin in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 1997;26:621–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levacher S, Letoumelin P, Pateron D. et al. Early administration of terlipressin plus glyceryl trinitrate to control active upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Lancet 1995;346:865–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seo YS, Park SY, Kim MY. et al. Lack of difference among terlipressin, somatostatin, and octreotide in the control of acute gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. Hepatology 2014;60:954–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bernard B, Cadranel JF, Valla D. et al. Prognostic significance of bacterial infection in bleeding cirrhotic patients: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 1995;108:1828–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pauwels A, Mostefa-Kara N, Debenes B. et al. Systemic antibiotic prophylaxis after gastrointestinal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients with a high risk of infection. Hepatology 1996;24:802–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goulis J, Armonis A, Patch D. et al. Bacterial infection is independently associated with failure to control bleeding in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology 1998;27:1207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT. et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis after endoscopic therapy prevents rebleeding in acute variceal hemorrhage: a randomized trial. Hepatology 2004;39:746–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tandon P, Abraldes JG, Keough A. et al. Risk of bacterial infection in patients with cirrhosis and acute variceal hemorrhage, based on Child-Pugh class, and effects of antibiotics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bernard B, Grange JD, Khac EN. et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 1999;29:1655–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fernandez J, Ruiz del Arbol L, Gomez C. et al. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1049–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Augustin S, Altamirano J, Gonzalez A. et al. Effectiveness of combined pharmacologic and ligation therapy in high-risk patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA. et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1527–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Laine L, El-Newihi HM, Migikowsky B. et al. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Villanueva C, Piqueras M, Aracil C. et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol 2006;45:560–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sarin SK, Nundy S.. Balloon tamponade in the management of bleeding oesophageal varices. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1984;66:30–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Avgerinos A, Armonis A.. Balloon tamponade technique and efficacy in variceal haemorrhage. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1994;207:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wright G, Lewis H, Hogan B. et al. A self-expanding metal stent for complicated variceal hemorrhage: experience at a single center. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Escorsell À, Pavel O, Cárdenas A. et al. ; Variceal Bleeding Study Group. Esophageal balloon tamponade versus esophageal stent in controlling acute refractory variceal bleeding: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology 2016;63:1957–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Azoulay D, Castaing D, Majno P. et al. Salvage transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for uncontrolled variceal bleeding in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2001;35:590–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marot A, Trépo E, Doerig C. et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: self-expanding metal stents in patients with cirrhosis and severe or refractory oesophageal variceal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:1250–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rudler M, Rousseau G, Thabut D.. Salvage transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt followed by early transplantation in patients with Child C14-15 cirrhosis and refractory variceal bleeding: a strategy improving survival. Transpl Int 2013;26:E50–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Monescillo A, Martinez-Lagares F, Ruiz-del-Arbol L. et al. Influence of portal hyper-tension and its early decompression by TIPS placement on the outcome of variceal bleeding. Hepatology 2004;40:793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C. et al. ; Early TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) Cooperative Study Group. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2010. 24;362:2370–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rudler M, Cluzel P, Corvec TL. et al. Early-TIPSS placement prevents rebleeding in high-risk patients with variceal bleeding, without improving survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:1074–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Deltenre P, Trépo E, Rudler M. et al. Early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;27:e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sharma P, Agrawal A, Sharma BC. et al. Prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy in acute variceal bleed: a randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus no lactulose. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;26:996–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maharshi S, Sharma BC, Srivastava S. et al. Randomised controlled trial of lactulose versus rifaximin for prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with acute variceal bleed. Gut 2015;64:1341–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. et al. Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sheibani S, Khemichian S, Kim JJ. et al. Randomized trial of 1-week versus 2-week intervals for endoscopic ligation in the treatment of patients with esophageal variceal bleeding. Hepatology 2016;64:549–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. García-Pagán JC, Villanueva C, Albillos A. et al. ; Spanish Variceal Bleeding Study Group. Nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate alone or associated with band ligation in the prevention of recurrent bleeding: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Gut 2009;58:1144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kumar A, Jha SK, Sharma P. et al. Addition of propranolol and isosorbide mononitrate to endoscopic variceal ligation does not reduce variceal rebleeding incidence. Gastroenterology 2009;137:892–901.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gozalez R, Zamora J, Gomez-Camarero J. et al. Combination endoscopic and drug therapy to prevent variceal rebleeding in cirrhosis. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Puente A, Hernández-Gea V, Graupera I. et al. Drugs plus ligation to prevent rebleeding in cirrhosis: an updated systematic review. Liver Int 2014;34:823–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sersté T, Melot C, Francoz C. et al. Deleterious effects of beta-blockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology 2010;52:1017–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P. et al. Nonselective β blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1680–90.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Leithead JA, Rajoriya N, Tehami N. et al. Non-selective β-blockers are associated with improved survival in patients with ascites listed for liver transplantation. Gut 2015;64:1111–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sinha R, Lockman KA, Mallawaarachchi N. et al. (16 February 2016) Carvedilol use is associated with improved survival in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites. J Hepatol 2017;67:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Holster IL, Tjwa ET, Moelker A. et al. Covered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic therapy + β-blocker for prevention of variceal rebleeding. Hepatology 2016;63:581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sauerbruch T, Mengel M, Dollinger M. et al. ; German Study Group for Prophylaxis of Variceal Rebleeding. Prevention of rebleeding from esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis receiving small-diameter stents versus hemodynamically controlled medical therapy. Gastroenterology 2015;149:660–8.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bureau C, Péron JM, Alric L. et al. ‘ A la carte’ treatment of portal hypertension: Adapting therapy to hemodynamic response for the prevention of bleeding. Hepatology 2002;36:1361–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Villanueva C, López-Balaguer JM, Aracil C. et al. Maintenance of hemodynamic response to treatment for portal hypertension and influence on complications of cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2004;40:757–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Reiberger T, Ulbrich G, Ferlitsch A. et al. Carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non-response to propranolol. Gut 2013;62:1634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Villanueva C, Graupera I, Aracil C. et al. A Randomized trial to assess whether portal pressure guided therapy to prevent variceal rebleeding improves survival in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2017;65:1693–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Aracil C. et al. ; BLEPS Study Group. Addition of simvastatin to standard therapy for the prevention of variceal rebleeding does not reduce rebleeding but increases survival in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1160–70.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chang FM,, Wang YP,, Lang HC. et al. (20 March 2017) Statins decrease the risk of decompensation in hepatitis B virus- and hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: a population-based study. Hepatology. doi: 10.1002/hep.29172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC. et al. ; Cirrhosis Asian Lamivudine Multicentre Study Group. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1521–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wong GL, Chan HL, Mak CW. et al. Entecavir treatment reduces hepatic events and deaths in chronic hepatitis B patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 2013;58:1537–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Li CZ, Cheng LF, Li QS. et al. Antiviral therapy delays esophageal variceal bleeding in hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:6849–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nahon P, Bourcier V, Layese R. et al. ; ANRS CO12 CirVir Group. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with cirrhosis reduces risk of liver and non-liver complications. Gastroenterology 2017;152:142–56.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bell H, Jahnsen J, Kittang E. et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a 15-year follow-up study of 100 Norwegian patients admitted to one unit. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:858–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ratziu V, Bonyhay L, Di Martino V. et al. Survival, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma in obesity-related cryptogenic cirrhosis. Hepatology 2002;35:1485–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L. et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:367–78.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]