Abstract

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), a perfluoroalkyl substance, is commonly detected in the serum of pregnant women and may impact fetal development via epigenetic re-programming. In a pilot study, we explored associations between serum PFOA concentrations during pregnancy and offspring peripheral leukocyte DNA methylation at delivery in women with high (n = 22, range: 12–26 ng/mL) and low (n = 22, range: 1.1–3.1 ng/mL) PFOA concentrations. After adjusting for cell type, child sex, and income, we did not find differences in CpG methylation in the two exposure groups that reached epigenome-wide significance. Among the 20 CpGs with the lowest p-values we found that seven CpG sites in three genes differed by exposure status. In a confirmatory cluster analysis, these 20 CpGs clustered into two groups that perfectly identified exposure status. Future studies with larger sample sizes should confirm these findings and determine if PFOA-associated changes in DNA methylation underlie potential health effects of PFOA.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Children’s health, DNA methylation, Environmental chemicals, Perfluoroalkyl substances

1. Introduction

Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are man-made fluorinated chemicals used in some stain/water resistant textile coatings, non-stick cookware, food container coatings, floor polish, fire-fighting foam, and industrial surfactants (EFSA, 2008). There is concern over the potential adverse health effects of PFAS, including the PFAS perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), due to their widespread use, biological persistence, detection in the blood of pregnant women and neonates, and association with adverse human health outcomes (Anon, 2008; Braun, 2016; Kato et al., 2014).

The developing fetus and infant may be especially sensitive to PFOA exposure because they have less developed biologically protective mechanisms and enhanced sensitivity to environmental toxicants. Cellular growth and large-scale epigenetic programming of lineage development that occur early in development could be affected by PFOA exposure and have long lasting impacts on various health outcomes (Jirtle and Skinner, 2007). Thus, changes in DNA methylation may be early markers of PFAS-induced alterations in fetal programming.

Several studies have reported that PFOA or perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) exposures are associated with lower global DNA cytosine methylation in neonates, higher Long Interspersed Nuclear Element-1 (LINE-1) methylation in adults, changes in the expression of cholesterol metabolism genes in adults, and decreased insulin-like growth factor-2 methylation in neonates (Guerrero-Preston et al., 2010; Watkins et al., 2014; Fletcher et al., 2013; Kobayashi et al., 2016). However, we are not aware of any studies that have examined epigenome-wide DNA methylation to identify PFOA-affected biological pathways. The purpose of this prospective pilot study was to determine if maternal serum PFOA concentrations during pregnancy were associated with differences in newborn peripheral leukocyte DNA methylation.

2. Materials and methods

We conducted a pilot study using data from 44 mother-infant pairs in the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study, a prospective pregnancy and birth cohort that recruited pregnant women in the greater Cincinnati, OH metropolitan area between March 2003 and January 2006. See the Supplemental Methods for additional details about the presented study and Braun et al. for additional details regarding participant eligibility, recruitment, and follow-up (Braun et al., 2016). The institutional review boards of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and the cooperating delivery hospitals approved this study, and all women provided informed consent for themselves and their infants.

We collected blood samples from women at ∼16 weeks of pregnancy during their prenatal clinic appointments and measured serum PFOA concentrations using online solid phase extraction coupled to high performance liquid chromatography-isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry (limit of detection: 0.1 ng/mL) (Kato et al., 2011). We examined 22 children born to women with the highest PFOA concentrations in the study (median: 15 ng/mL; range: 12–26) and 22 children born to women with the lowest concentrations (median: 2.5 ng/mL; range: 1.1–3.1) to estimate a potential range of effect sizes. For all analyses we dichotomized PFOA into high and low exposure groups.

We collected venous cord blood samples immediately after delivery by venipuncture, extracted DNA from frozen cord blood, and used the Illumina Infinium Human Methylation 450 BeadChip Kit to measure DNA methylation at 485,512 loci. We analyzed samples in four batches, and each row of each chip contained DNA from one high and one low PFOA group infant, with the columns counterbalanced. We followed recommended best practices to process, convert, and normalize raw DNA methylation data (Breton et al., 2017). After removing sex chromosomes, SNP-affected probes, cross-hybridizing probes, and probes having detection p-values > 0.05, the final data set included 358,933 autosomal probes.

Trained research assistants collected information about maternal age, education, household income, insurance, prenatal vitamin use, gestational age, and infant sex from questionnaires and medical records. We measured serum cotinine as a biomarker of tobacco smoke exposure. Due to the small sample size of this pilot study we considered only child sex and household income as potential confounders in the analysis. In addition, we estimated and adjusted for the proportion of B cells, CD4, CD8, granulocytes, monocytes, natural killer cells, and nucleated red blood cells using reference data from cord blood samples and an unsupervised optimal differentially methylated region subset finder to predict the proportions of each cell type for each subject in our data (Bakulski et al., 2016; Koestler et al., 2016).

We examined bivariate associations between covariates and PFOA exposure group. Then, after adjusting the methylation beta values for cell type, we used the Limma package (R version 3.2.1 version 3.2.1) to estimate the difference in the mean methylation beta values for those in the high exposure group compared to those in the low exposure group, adjusting for infant sex and income. We adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to calculate q-values to control the false discovery rate (FDR < 0.05) (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). This approach can be sensitive to outliers, thus, we performed a sensitivity analysis using robust linear regression.

We used the UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) to map exonic and intronic regions using the February 2009 human reference sequence (GRCh37) for genes with multiple CpG sites in the top 20 loci from our primary analysis (Kent, 2002). As a confirmatory analysis, we used k-means clustering to cluster individuals based on the top 20 loci. The optimal number of clusters was chosen by the cubic clustering criterion. We then cross-tabulated cluster with PFOA exposure group. Next, we calculated the proportion of significant (p < 0.001) and non-significant CpGs located in promoter and enhancer regions. Finally, we examined differences in cell type proportions between the high and low serum PFOA concentration groups. Analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institutes, Inc., Cary, NC) and in R (v3.0.0).

3. Results

On average, women in this pilot study were 31 years old at delivery and had an average annual household income of $73,600 (Table 1). Most women used prenatal vitamins (93%) and had a bachelor’s degree or higher (64%).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by prenatal PFOA group, n (%).

| Total (n = 44) | High PFOA exposure (n = 22) | Low PFOA exposure (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 31.3 ± 5.0 | 31.2 ± 5.7 | 31.5 ± 4.4 |

| Serum cotinine (ng/mL), GM ± SD | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.5 |

| Prenatal vitamin use, Yes | 41 (93) | 20 (91) | 21 (95) |

| Annual household income (thousands), mean ± SD | 73.6 ± 47.0 | 74.5 ± 42.2 | 72.7 ± 52.4 |

| Education | |||

| < Bachelor’s degree | 16 (36) | 9 (41) | 7 (32) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 28 (64) | 13 (59) | 15 (68) |

| Newborn characteristics | |||

| Gestational age (weeks), mean ± SD | 39.4 ± 1.3 | 39.5 ± 1.4 | 39.2 ± 1.3 |

| Infant sex, Male | 23 (52) | 11 (50) | 12 (55) |

| PFOA (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 7.5 (2.4, 15) | 15 (13, 17)* | 2.4 (2.0, 2.6)* |

Statistically significant difference between exposure groups (p < 0.05).

In adjusted linear regression models, there were no differences in methylation at any CpG sites in the two PFOA exposure groups at a false discovery rate < 0.05 level (Table 2). The distribution of p-values slightly deviates from the null expected distribution for those near statistical significance (Supplemental Figure 1). Results did not change appreciably in sensitivity analyses using robust linear regression. Among the 20 CpGs with the smallest p-values, we found seven CpG sites in three genes that were hypomethylated in women who had higher PFOA exposure compared with women who had lower exposure. We highlight these seven CpGs because they were associated with PFOA more than once in a particular gene. The seven CpGs were found in RASA3 (n = 3), UCK1 (n = 2), and OPRD1 (n = 2) with q-values ranging from 0.133 to 0.339 (p-values ≤ 1.87e–05). In each gene, these CpGs were located in close proximity to each other (< 200 base pairs); most were in intronic regions (Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Table 1). In addition, the loci associated with PFOA exposure (p < 0.001) were more likely to be located in promoter regions (23.8 vs 16.3%; Fig. 1, Supplemental Table 2) compared to loci not associated with PFOA.

Table 2.

Top 20 CpG sites (ranked by p-value) out of 358,933 total sites. Methylation beta values adjusted for cell type, child sex, and household income.

| Name | P value adjusted | Q value | Gene name | Chromosome | Difference in Mean Methylation Percentage (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg23312375 | 5.83e–07 | 0.133 | RASA3 | 13 | −0.051 (−0.068, −0.034) |

| cg13557773 | 7.39e–07 | 0.133 | RASA3 | 13 | −0.059 (−0.079, −0.039) |

| cg24541426 | 1.98e–06 | 0.162 | HOXD3 | 2 | −0.005 (−0.007, −0.003) |

| cg00478851 | 2.14e–06 | 0.162 | PPFIBP2 | 11 | −0.026 (−0.035, −0.017) |

| cg23132774 | 2.28e–06 | 0.162 | RASA3 | 13 | −0.056 (−0.076, −0.035) |

| cg23978968 | 2.71e–06 | 0.162 | S1PR1 | 1 | −0.023 (−0.032, −0.015) |

| cg07957491 | 4.22e–06 | 0.180 | UCK1 | 9 | −0.032 (−0.044, −0.020) |

| cg10782875 | 4.25e–06 | 0.180 | CACNG8 | 19 | 0.008 (0.005, 0.011) |

| cg06658816 | 4.59e–06 | 0.180 | 1 | −0.007 (−0.010, −0.005) | |

| cg13629999 | 5.00e–06 | 0.180 | UCK1 | 9 | −0.011 (−0.015, −0.007) |

| cg27532187 | 1.02e–05 | 0.282 | RNF39 | 6 | −0.004 (−0.006, −0.003) |

| cg07837534 | 1.05e–05 | 0.282 | ARHGAP30 | 1 | 0.005 (0.003, 0.006) |

| cg15068522 | 1.08e–05 | 0.282 | RAB23 | 6 | −0.007 (−0.009, −0.004) |

| cg03987199 | 1.17e–05 | 0.282 | OPRD1 | 1 | −0.061 (−0.085, −0.037) |

| cg00138497 | 1.18e–05 | 0.282 | EDF1 | 9 | −0.008 (−0.012, −0.005) |

| cg13970591 | 1.59e–05 | 0.326 | REEP6,PCSK4 | 19 | −0.006 (−0.008, −0.004) |

| cg04994964 | 1.63e–05 | 0.326 | MT1M | 16 | −0.007 (−0.010, −0.004) |

| cg01787798 | 1.64e–05 | 0.326 | TNR | 1 | −0.052 (−0.073, −0.031) |

| cg02152233 | 1.87e–05 | 0.339 | OPRD1 | 1 | −0.061 (−0.087, −0.036) |

| cg05317207 | 1.89e–05 | 0.339 | ZNF497 | 19 | −0.082 (−0.116, −0.048) |

Q-values were calculated using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. CI = confidence interval.

Note: Difference in mean methylation percentage compares the high exposure group to the low exposure group.

Fig. 1.

Volcano plot showing the mean difference in leukocyte DNA methylation for high vs. low PFOA exposure group (x-axis) for each individual CpG site plotted against its negative log10 p-value (y-axis). Adjusted for cell type, child sex, and household income. Bar plot insert compares the location of statistically significant (p-value < 0.001) and non-significant CpGs.

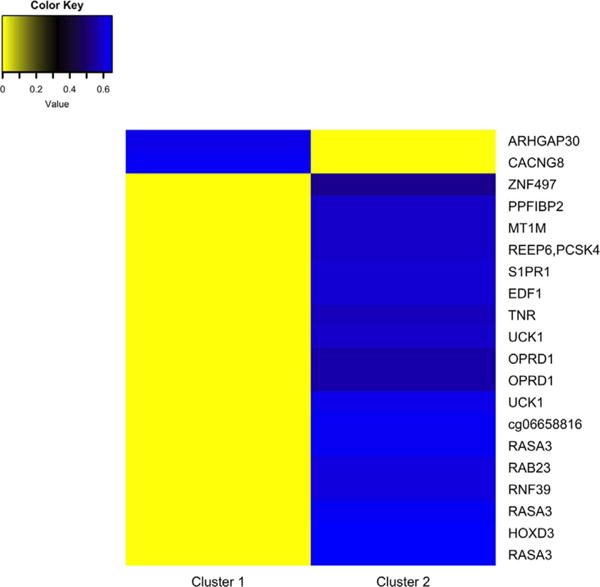

The top 20 CpGs identified two clusters of participants; Cluster 1 was characterized by lower methylation of 18 of the 20 CpGs and higher methylation of 2 CpGs compared with Cluster 2 (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 3). The clusters perfectly identified PFOA exposure group (χ2 p-value = 2.42e–10). The 22 infants born to women in the high PFOA exposure group all resided in Cluster 1, while the other 22 infants in the low exposure group resided in Cluster 2.

Fig. 2.

Heat map of the average DNA methylation in the top 20 loci associated with maternal serum PFOA concentrations by cluster. Yellow indicates less methylation and blue indicates more methylation. Cluster 1 corresponded to the high PFOA exposure group and Cluster 2 corresponded to the low PFOA exposure group.

Finally, using a reference-based method, we found no statistically significant differences in cell type proportions between the exposure groups after adjusting for child sex and annual household income (Supplemental Table 4). The p-values obtained from the t-tests comparing cell proportion in the two groups were > 0.50.

4. Discussion

In this pilot study, prenatal serum PFOA concentrations were associated with cord blood leukocyte DNA methylation in seven CpG sites located in three genes: RASA3, OPRD1, and UCK1. While we did not find significant differences in DNA methylation among women who had higher versus lower serum PFOA concentration at the epigenome-wide significance level, we found a higher proportion of statistically significant CpGs (p-value < 0.001) located in promoter regions. In a confirmatory analysis, we found that the top 20 CpGs associated with PFOA exposure were able to perfectly discriminate PFOA exposure status.

We are aware of four prior studies examining the relations between PFOA exposure and epigenetic outcomes in humans. Somewhat consistent with our findings of lower methylation, a prior study reported an inverse association between serum PFOA and cord blood leukocyte global DNA methylation. Another study of 177 infants found that prenatal PFOA exposure was associated with a decrease in cord blood DNA methylation of IGF2, but not H19 or LINE-1 (Kobayashi et al., 2016). In adults that were highly exposed to PFOA via contaminated drinking water, two studies examined LINE-1 methylation and candidate gene expression (Watkins et al., 2014; Fletcher et al., 2013). No statistically significant associations were found between PFOA and LINE-1 DNA methylation (Watkins et al., FebF 2014). However, PFOA was associated with reduced expression of several genes involved in cholesterol metabolism — NR1H2 (LXRB), ABCG1 and NPC1 — possibly indicating hypermethylation of CpGs of those genes (Fletcher et al., 2013).

Among the top 20 genes associated with PFOA exposure in this study, several have been associated with fetal programming or diseases linked to PFOA exposure. RASA3 (RAS P21 Protein Activator 3) encodes a protein that negatively regulates the Ras signaling pathway which is involved in cell growth and differentiation (Walker et al., 2002). The inverse association between PFOA and RASA3 hypomethylation in this study suggests that the Ras signaling pathway activity, and related cell growth and differentiation, could be reduced in infants with high prenatal PFOA exposure. This finding may be related to observations from epidemiological and animal studies showing that prenatal PFOA exposure is associated with reduced fetal growth and lower birth weight (Johnson et al., 2014; Koustas et al., 2014). The OPRD1 (Opioid Receptor Delta 1), which was hypomethylated in PFOA exposed infants, encodes a protein associated with morphine and heroin dependence (Gelernter and Kranzler, 2000). A single nucleotide polymorphisms of OPRD1 (rs569356) has been linked to body mass index and waist circumference in adolescent and adult males (Kvaloy et al., 2013), raising the possibility that methylation of this gene mediates previously observed associations between PFOA exposure and obesity (Braun, 2016; Braun et al., 2016). Given that we found a higher proportion of statistically significant associations (p < 0.001) in promoter regions than compared to other regions future studies should confirm if altered gene expression may be an important mode of action of PFOA.

While there is strong evidence suggesting that PFOA is immunotoxic to humans (Anon, 2016), we did not observe evidence that PFOA exposure was associated with immune cell profiles among these neonates. However, we could not examine less numerous cells (e.g. myeloid suppressors, T-regulatory cells, dendritic cells) or activated immune cells that might be important contributors to small methylation differences. For example, RASA3 is involved in integrin signaling and has a well-known role in immune activation (Schurmans et al., 2015). Thus, it is still possible that our top loci represent signals from an altered immune response.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. First, the small sample size of this pilot study limits our ability to detect statistically significant associations at the epigenome-wide level. However, we were able to examine several potential biological pathways that PFOA may affect to influence subsequent child and adult health. Second, while we adjusted for seven different immune cell types, a potentially important confounder that prior global methylation studies have not considered, the reference set used to estimate cell type proportions does not include small subtypes of cells potentially leading to misclassification of our DNA methylation values (Guerrero-Preston et al., 2010; Watkins et al., 2014; Fletcher et al., 2013; Kobayashi et al., 2016). Third, we measured cord blood DNA methylation, which is not specific to all target tissues of interest. Future studies should measure DNA methylation in additional tissues, such as adipose. Finally, we were not able to adjust for all potential confounders that may be associated with changes in PFOA exposure and DNA methylation.

In this cohort, higher serum PFOA concentrations during pregnancy were associated with DNA methylation at several CpG sites in cord blood leukocytes, including several genes potentially involved in childhood and adult diseases associated with early life PFOA exposure. While we did not observe epigenome-wide level significance, these results highlight the potential for prenatal PFOA exposure to affect several biological pathways involved in the etiology of chronic disease. Future studies with larger sample sizes should confirm these findings and determine if PFOA-induced changes in DNA methylation mediate the association between prenatal exposure to PFOA and adverse health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Antonia Calafat and the CDC laboratory staff who performed the PFAS assays.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH under R01 ES025214, R01ES020349, R01 CA207110, and P01ES11261; a Junior Faculty Research Awards in Genetic & Molecular Population Studies from the Brown University School of Public Health; and a Doctoral Fellowship from the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.013.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Bakulski KM, Feinberg JI, Andrews SV, et al. DNA methylation of cord blood cell types: applications for mixed cell birth studies. Epigenetics: Off J DNA Methylation Soc. 2016;11(5):354–362. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1161875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM. Early-life exposure to EDCs: role in childhood obesity and neurodevelopment. Nat Rev: Endocrinol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Chen A, Romano ME, et al. Prenatal perfluoroalkyl substance exposure and child adiposity at 8 years of age: the HOME study. Obesity. 2016;24(1):231–237. doi: 10.1002/oby.21258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Kalloo G, Chen A, et al. Cohort profile: the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton CV, Marsit CJ, Faustman E, et al. Small-magnitude effect sizes in epigenetic end points are important in Children’s Environmental Health Studies: the Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center’s Epigenetics Working Group. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(4):511–526. doi: 10.1289/EHP595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Perfluoroctane sulfonate, perfluorooctanoic acid and their salts: Scientific opinion of the panel on contaminants in the food chain. EFSA J. 2008;653:1–131. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2008.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher T, Galloway TS, Melzer D, et al. Associations between PFOA, PFOS and changes in the expression of genes involved in cholesterol metabolism in humans. Environ Int. 2013:57–58. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Kranzler HR. Variant detection at the δ opioid receptor (OPRD1) locus and population genetics of a novel variant affecting protein sequence. Hum Genet. 2000;107(1):86–88. doi: 10.1007/s004390000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Preston R, Goldman LR, Brebi-Mieville P, et al. Global DNA hypo-methylation is associated with in utero exposure to cotinine and perfluorinated alkyl compounds. Epigenetics: Off J DNA Methylation Soc. 2010;5(6):539–546. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.6.12378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(4):253–262. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PI, Sutton P, Atchley DS, et al. The navigation guide — evidence-based medicine meets environmental health: systematic review of human evidence for PFOA effects on fetal growth. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(10):1028–1039. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Basden BJ, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Improved selectivity for the analysis of maternal serum and cord serum for polyfluoroalkyl chemicals. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218(15):2133–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Wong LY, Chen A, et al. Changes in serum concentrations of maternal poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances over the course of pregnancy and predictors of exposure in a multiethnic cohort of Cincinnati, Ohio pregnant women during 2003–2006. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(16):9600–9608. doi: 10.1021/es501811k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet C, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Azumi K, Goudarzi H, et al. Effects of prenatal perfluoroalkyl acid exposure on cord blood IGF2/H19 methylation and ponderal index: the Hokkaido study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/jes.2016.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koestler DC, Jones MJ, Usset J, et al. Improving cell mixture deconvolution by identifying optimal DNA methylation libraries (IDOL) BMC Bioinform. 2016;17:120. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-0943-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koustas E, Lam J, Sutton P, et al. The navigation guide-evidence-based medicine meets environmental health: systematic review of nonhuman evidence for PFOA effects on fetal growth. Environ Health Perspect. 2014 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvaloy K, Kulle B, Romundstad P, Holmen TL. Sex-specific effects of weight-affecting gene variants in a life course perspective–The HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Obes. 2013;37(9):1221–1229. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Services UDoHaH, editor. OHAT, NTP. Systematic review of immunotoxicity associated with exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schurmans S, Polizzi S, Scoumanne A, Sayyed S, Molina-Ortiz P. The Ras/Rap GTPase activating protein RASA3: from gene structure to in vivo functions. Adv Biol Regul. 2015;57:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SA, Kupzig S, Lockyer PJ, Bilu S, Zharhary D, Cullen PJ. Analyzing the role of the putative inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate receptor GAP1IP4BP in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(50):48779–48785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204839200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, Wellenius GA, Butler RA, Bartell SM, Fletcher T, Kelsey KT. Associations between serum perfluoroalkyl acids and LINE-1 DNA methylation. Environ Int. 2014;63:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.