Abstract

Summary: Rational design of drug combinations has become a promising strategy to tackle the drug sensitivity and resistance problem in cancer treatment. To systematically evaluate the pre-clinical significance of pairwise drug combinations, functional screening assays that probe combination effects in a dose–response matrix assay are commonly used. To facilitate the analysis of such drug combination experiments, we implemented a web application that uses key functions of R-package SynergyFinder, and provides not only the flexibility of using multiple synergy scoring models, but also a user-friendly interface for visualizing the drug combination landscapes in an interactive manner.

Availability and Implementation: The SynergyFinder web application is freely accessible at https://synergyfinder.fimm.fi; The R-package and its source-code are freely available at http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/synergyfinder.html.

1 Introduction

Making cancer treatment more personalized and effective is one of the grand challenges of our health care system. However, multiple clinical studies have shown that even when there is a dramatic initial treatment response, cancer cells with high mutational potential and functional redundancy can easily develop drug resistance via a network of compensating or bypassing pathways (Knight et al., 2010). For improved efficacy, there is a critical need to identify drug combinations, which target both the cancer driver and bypass signals (Al-Lazikani et al., 2012).

Recently, high-throughput drug screening has made it possible to assay a large number of compounds, where a pair of drugs is plated in a dose–response matrix, thus enabling the assessment of drug combination effects at various dose levels (Mathews Griner et al., 2014; Mott et al., 2015). To quantify the degree of synergy or antagonism, the combination response is often compared against the expected combination response, under the assumption of non-interaction calculated using a reference model (Tang et al., 2015). Commonly-utilized reference models include the Highest single agent (HSA) model (Berenbaum, 1989), the Loewe additivity model (Loewe, 1953), the Bliss independence model (Bliss, 1939), and more recently, the Zero interaction potency (ZIP) model (Yadav et al., 2015). The assumptions being made in these reference models are different from each other, which may produce inconsistent conclusions about the degree of synergy. Software tools that allow for comparison of different reference models are therefore highly needed for an unbiased analysis of drug combination experiments (e.g. Di Veroli et al., 2016).

To address these needs, we implemented SynergyFinder, a web application for the preprocessing and visualization of the drug combination dose–response data. The tool implements synergy scoring with four major reference models: HSA, Loewe, Bliss and ZIP models. The degree of a drug combination effect can be readily visualized as a synergy landscape map over the dose matrix. Dose regions that show strong synergy or antagonism can be zoomed-in for more detailed analyses and interpretation about clinical feasibility of the combination. To the best of our knowledge, SynergyFinder introduces the first publicly available web-application based on an open-source R-package for analyzing high-throughput drug combination dose–response matrix data.

2 Implementation

2.1 General overview

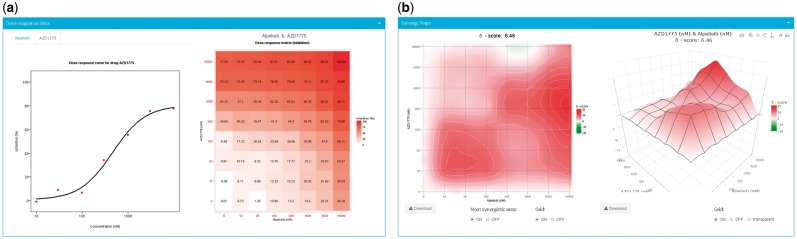

The SynergyFinder R package implements algorithms to calculate synergy scores for dose–response matrix data. Currently, four reference models are available: (i) HSA model, where the synergy score quantifies the excess over the highest single drug response; (ii) Loewe model, where the synergy score quantifies the excess over the expected response if the two drugs are the same compound; (iii) Bliss model, where the expected response is a multiplicative effect as if the two drugs act independently; and (iv) ZIP model, where the expected response corresponds to an additive effect as if the two drugs do not affect the potency of each other. Yadav et al., 2015 presented a detailed comparison of these reference model. The front-end web application offers a user-friendly and interactive graphical interface for visualization of drug combination data and the calculated synergy scores either as a two-dimensional or a three-dimensional synergy map over the dose matrix (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The outcome panels of the SynergyFinder web application. (a) Visualization of the dose–response matrix and the plots of phenotypic responses for the single drugs. (b) Visualization of the calculated 2D and 3D synergy maps

2.2 Data submission and preprocessing

The default input is a text file that includes the annotations of the dose–response matrices for drug pairs which include drug names, concentrations and phenotypic responses. The number of drug combinations provided in the input file is unrestricted. For each drug combination, the dose–response matrix should contain at least three rows and three columns so that sensible synergy scores can be calculated. After the input file has been successfully uploaded, the types of phenotypic responses need to be specified. Thereafter a data visualization tab will be created for each drug combination, where the user may obtain an overview of the full dose–response matrix, as well as the dose–response curves for the single drugs, fitted by four-parameter logistic models. The visualizations enable the user to identify any problematic data points, such as negative phenotypic responses or outliers for which a drug combination reference model may not be properly fitted.

2.3 Calculation of synergy scores and their visualization

Given a reference model specified by the ‘Method’ parameter, an overall synergy score is calculated as the deviation of phenotypic responses compared to the expected values, averaged over the full dose–response matrix. Visualization of the synergy scores may be obtained by switching on the ‘Visualize synergy scores’ toggle-bar. In the 2D plot, the user may zoom in by brushing and double-clicking a certain region, and then save the zoomed synergy map as a new figure in PDF format. The overall synergy score corresponding to this selected dose region will be shown accordingly in the figure caption. In the 3D plot, the individual synergy score at each dose combination can be displayed by hovering the mouse. The synergy map can be rotated and downloaded as publication quality SVG or PNG image or interactive plot in HTML format.

2.4 Reporting

SynergyFinder generates the results in PDF format for all or a subset of the drug combinations, depending on the user’s choices. The dose response matrices and the synergy maps can be generated accordingly. The calculated synergy scores can be downloaded as a table. We provided also an enhanced dynamic report which allows the user to specify the viewing angle of the 3D synergy map

2.5 Tutorial and feedback

The SynergyFinder web application is implemented using R and hosted by Open Source Shiny Server. To facilitate its usage, an interactive web tour, a video tutorial, a user guide documentation and example input data can be found on the website. The user may leave comments or suggestions for improvements using the feedback form. For the users with R programming experience, the SynergyFinder R-package provides the source code to run the drug combination analyses independently of the web application and allows other developers to extend its key functions.

3 Conclusion

The SynergyFinder web-application facilitates the visualization and analysis of drug combination data from high-throughput dose–response matrix assays. Use of multiple reference models on the full dose–response matrix should provide an unbiased and straightforward way to evaluate the pre-clinical significance of drug combinations toward exciting clinical applications.

In the future, we plan to provide more flexibility for analyzing drug combination data, e.g. by alternative curve-fitting functions for single drugs and missing value imputation, as well as means to assess the statistical significance of synergy using replicate measurements.

Funding

Academy of Finland (grants 272437, 269862, 279163, 292611, 295504); the Cancer Society of Finland. European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 634143 (MedBioinformatics).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Al-Lazikani B. et al. (2012) Combinatorial drug therapy for cancer in the postgenomic era. Nat. Biotechnol., 30, 679–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum M.C. (1989) What is synergy. Pharmacol. Rev., 41, 93–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss C.I. (1939) The toxicity of poisons applied jointly. Ann. Appl. Biol., 26, 585–615. [Google Scholar]

- Di Veroli G.Y. et al. (2016) Combenefit: an interactive platform for the analysis and visualization of drug combinations. Bioinformatics, 32, 2866–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight Z.A. et al. (2010) Targeting the cancer kinome through polypharmacology. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 10, 130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewe S. (1953) The problem of synergism and antagonism of combined drugs. ArzneimiettelForschung, 3, 286–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews Griner L.A. et al. (2014) High-throughput combinatorial screening identifies drugs that cooperate with ibrutinib to kill activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 111, 2349–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott B.T. et al. (2015) High-throughput matrix screening identifies synergistic and antagonistic antimalarial drug combinations. Sci. Rep., 5, 13891.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J. et al. (2015) What is synergy? The saariselkä agreement revisited. Front. Pharmacol., 6, 181.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav B. et al. (2015) Searching for drug synergy in complex dose–response landscapes using an interaction potency model. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J., 13, 504–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]