Abstract

Purpose of Review

Denosumab is an inhibitor of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), and has emerged as an important novel therapy for skeletal disorders. This article examines the use of denosumab in children.

Recent findings

Considerable safety and efficacy data exists for denosumab treatment of adults with osteoporosis, bone metastases, and giant cell tumors. Pediatric data is limited; however, evidence suggests denosumab may be beneficial in decreasing bone turnover, increasing bone density, and preventing growth of certain skeletal neoplasms in children. Denosumab’s effect on bone turnover is rapidly reversible after drug discontinuation, representing a key difference from bisphosphonates. Rebound increased bone turnover has led to severe hypercalcemia in several pediatric patients.

Summary

Denosumab is a promising therapy for pediatric skeletal disorders. At present, safety concerns related to rebounding bone turnover and mineral homeostasis impact use of denosumab in children. Research is needed to determine if and how these effects can be mitigated.

Keywords: RANKL, OPG, osteoporosis, giant cell tumors, osteogenesis imperfect, bone turnover rebound, hypercalcemia

Introduction

Despite recent advances in understanding of the pathogeneses of skeletal disorders in children, clinical management remains challenging, in large part because of the paucity of bone-altering therapies available for pediatric use. Denosumab is a new class of anti-resorptive medication and inhibitor of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), which has emerged as an important novel therapy for osteoporosis, malignancies, and other skeletal disorders. The scope of this article is to describe the mechanism of action of denosumab, to review existing safety and efficacy data in adults and children, and to discuss the potential benefits and critical knowledge gaps in the application of this therapy to children.

The Role of RANKL in Bone Modeling and Remodeling

The skeleton is continuously renewed through bone remodeling; a lifelong process in which mature bone is broken down by osteoclasts and new bone is formed by osteoblasts. This process is tightly coupled in order to maintain calcium homeostasis and to repair skeletal microdamage that accumulates over time [1]. In children, linear growth occurs through strictly regulated, site-specific uncoupling of bone formation and resorption, termed bone modeling. Bone formation on the outer periosteal surface increases bone size, while resorption expands the marrow cavity and sculpts the outer surface of the bone [2]. The net result of bone modeling is an increase in bone size and mass.

Many skeletal disorders are characterized by disruption of the bone remodeling cycle. A relative increase in resorption and/or decrease in formation lead to a net loss in bone mass, changes in bone microarchitecture, and increased risk of fracture. These are common processes in children with chronic illnesses, who have multiple risk factors related to mobility, nutrition, and exposure to bone-toxic therapies [3]. In addition, osteolytic disorders such as primary tumors and metastases result in bone destruction through localized activation of osteoclasts [4]. Therapeutic strategies to treat these disorders include targeting the bone remodeling cycle through anti-resorptive medications that inhibit osteoclasts, and/or anabolic therapies that promote osteoblast activity.

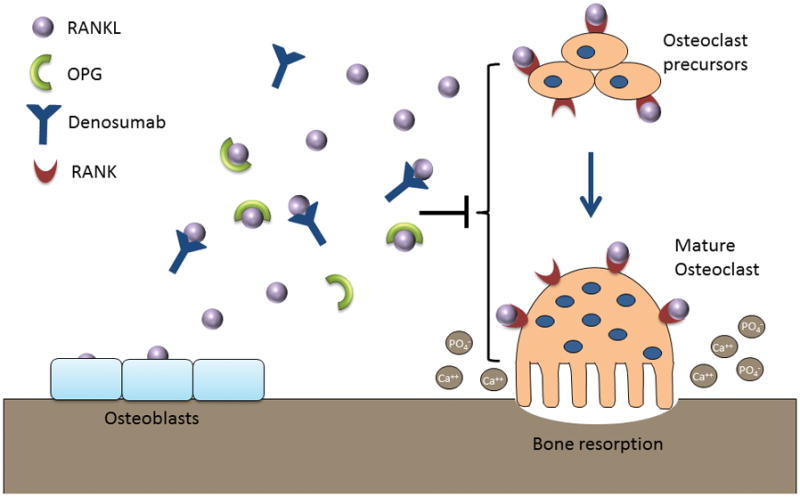

A primary regulator of bone resorption is Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa-B Ligand (RANKL), a transmembrane protein from the superfamily of the tumor necrosis factor receptors which is highly expressed by osteoblasts [5]. After binding to the Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa-B (RANK) on the surface of osteoclasts and pre-osteoclasts, RANKL promotes osteoclast differentiation and activity, leading to increased bone resorption [6] (Figure 1). Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a soluble, non-signaling glycoprotein produced by osteoblasts that acts as a “decoy receptor”, preventing the binding of RANKL to its receptor and blocking its catabolic effects [7]. The balance between RANKL and OPG is thus an important determinate of skeletal homeostasis, and discrepancy between these factors has been implicated in multiple disease processes, including post-menopausal osteoporosis, inflammatory disorders, and cancer-related bone loss [8].

Figure 1. Regulation of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption.

RANKL is expressed by osteoblasts and binds to RANK on the surface of osteoclast precursors and mature osteoclasts. This binding stimulates osteoclast differentiation, activity, and survival, leading to bone resorption and release of calcium and phosphorus into the serum. OPG is a non-signaling decoy receptor which binds RANKL and prevents its interaction with RANK. The balance between RANKL and OPG is thus an important determinant of bone resorption and mineral homeostasis. Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, which similar to OPG binds to RANKL and inhibits its effect on osteoclast activity. RANKL = receptor activator of nuclear kappa-B ligand; RANK = receptor activator of nuclear kappa-B, OPG = osteoprotegerin.

Denosumab

Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody of the IgG2 immunoglobulin isotype to RANKL. It binds with high affinity and specificity to RANKL, mimicking the inhibitory effects of OPG and resulting in rapid suppression of bone resorption. The pharmacokinetics of denosumab have been studied extensively in adults, and are similar to other fully human monoclonal antibodies, exhibiting dose-dependent, non-linear elimination [9 10]. In adults given 60 mg subcutaneously, serum concentrations decline after 4–5 months with a half-life of approximately 30 days. Repeated doses of 60 mg every 6 months result in minimal drug accumulation, with an increase in bone turnover markers towards baseline values at the end of each dosing interval. Doses above 60 mg result in dose-dependent increases in exposure, and at 120 mg monthly reaches steady-state after 4–5 doses, with continuous suppression of bone turnover throughout dosing intervals. These data inform the 2 commercially available formulations of denosumab: Prolia, administered as 60 mg subcutaneously every 6 months, and Xgeva, administered as 120 mg subcutaneously once monthly after 3 weekly loading doses (Amgen, Inc).

The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of denosumab in children are unknown; however, they are likely to be impacted by pediatric-specific factors. Monoclonal antibody dosing in children is typically scaled down to account for decreased body weight and surface area [11]. Because denosumab elimination is non-linear due to its interaction with RANKL, dosing must also take into account relative levels of RANK/RANKL/OPG activity. The increased skeletal metabolism related to bone modeling and growth in children is therefore likely to impact both pediatric dosage and dosing intervals.

Current Indications

Osteoporosis

Denosumab was initially marketed as Prolia for treatment of post-menopausal osteoporosis. Four phase 3 trials have been conducted in this population, including the pivotal FREEDOM study, which was the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial of denosumab to demonstrate a decrease in vertebral and non-vertebral fractures [12]. Similar findings were reported in subsequent trials that included both post-menopausal women and men with osteoporosis [13 14]. Additional studies comparing the efficacy of denosumab and alendronate showed higher gains in bone mineral density (BMD) and greater reductions in bone turnover in denosumab-treated subjects [15–17]. An ongoing, open-label FREEDOM extension arm has reported continued gains in BMD and reductions in bone-turnover with up to 8-years of treatment [18].

Sex steroid deprivation is a common treatment strategy for hormone responsive cancers, and denosumab has been studied in two phase 3 trials for cancer treatment-induced bone loss. The Prolia formulation was found to increase BMD and prevent new vertebral fractures in a phase 3 study of men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer [19]. Similar findings were reported in a phase 3 study of women receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer, where denosumab was found to improve BMD [20]. Together these data led to denosumab’s approval for treatment of both postmenopausal osteoporosis and bone loss associated with sex steroid deprivation therapy [21]. Denosumab was overall well-tolerated in adult osteoporosis trials, with no significant increase in adverse events in comparison to placebo or alendronate.

Bone Metastases

Skeletal events in cancer patients include fracture, pain, and spinal cord compression, carrying a high risk of morbidity and mortality. The monthly Xgeva formulation has been investigated for prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases in three simultaneously conducted phase 3 trials. These included patients with breast [22], prostate [23], and advanced cancer or multiple myeloma [24], and each reported similar results, demonstrating delayed time to first on-study event in comparison to zoledronate. Overall survival and disease progression were similar in denosumab and zoledronate-treated patients, however an ad hoc subanalysis in patients with multiple myeloma favored zoledronate [24]. These results led to approval for prevention of skeletal-related events in adults with bone metastases from solid tumors; however, this indication does not extend to multiple myeloma [25].

Denosumab was generally well-tolerated in phase 3 cancer studies. The most common treatment-associated adverse event was hypocalcemia, which occurred more frequently in denosumab-treated patients (12.4 versus 5.3 percent in the zoledronate group)[26]. Time to first occurrence of hypocalcemia was also shorter in the denosumab group (median 3.8 versus 6.5 months), likely reflecting denosumab’s more potent effects on bone turnover.

Hypercalcemia

Anti-resorptives are frequently utilized for treatment of hypercalcemia due to their ability to inhibit osteoclast-mediated release of calcium into the serum. A phase 2 study in hypercalcemia of malignancy found that high dose monthly denosumab was highly effective at reducing serum calcium levels, with a median response time of 9 days and median duration greater than 3 months [27]. Additional support was provided by an ad hoc analysis of two large phase 3 trials of denosumab versus zoledronate treatment for patients with solid tumors, which found that denosumab significantly delayed time to development of first on-study hypercalcemia [28]. Based on these results, denosumab received approval for treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy refractory to bisphosphonates [25].

Hypercalcemia is a frequent complication of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with osteopetrosis, a disorder of high bone mass which may result from defects in RANK/RANKL signaling. Shroff et al report two children (age 3 and 12 years) with loss-of-function mutations in the TNFRSF11A gene encoding RANK, who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation resulting in robust activation of osteoclasts and refractory hypercalcemia. In both patients denosumab resulted in prompt normalization of serum calcium levels [29] (Table 1). Given its targeted activity against RANKL signaling, denosumab is an intuitive treatment choice for this indication.

Table 1.

Published reports of denosumab treatment in children and adolescents

| Indication & Reference | Patients &Reference | Dose | Duration | Response | On-Treatment Adverse Effects | Post-Treatment Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteopetrosis & hypercalcemia | ||||||

| 29 | 12 &3 yo girls | 0.13–0.27 mg/kg every 4–7 weeks | 14 months | Normalization of serum calcium | None | Unknown |

|

| ||||||

| Giant cell tumor | ||||||

| 32, 33 | 10 children ≥ 12 yo | 120 mg monthly | ongoing | Decreased tumor size, improved pain | None | Unknown |

| 34, 35 | 10 yo girl | 120 mg monthly | 24 months | Decreased tumor size, improved pain | Mild hypocalcemia & hypophosphatemia | Severe hypercalcemia |

| 36, 37 | 10 yo boy | 120 mg monthly | 14 months | Decreased tumor size, improved pain | None | Severe hypercalcemia |

|

| ||||||

| Osteogenesis imperfecta | ||||||

| 41, 42 | 4 boys age 5–18y (type 6) | 1 mg/kg every 8–12 weeks | 24 months | Increased BMD, improved pain | Mild hypocalcemia (1 patient) | Unknown |

| 43 | 23 mo boy (type 6) | 1 mg/kg every 4–12 weeks | 12 months | Increased BMD, improved mobility1 | Severe hypercalcemia2 | None |

| 44 | 10 children age 5–11 (types 1, 3 &4) | 1 mg/kg every 12 weeks | 12 months | Increased BMD | Mild hypocalcemia (1 patient) | Mild hypercalcemia |

|

| ||||||

| Juvenile Paget’s disease | ||||||

| 46 | 7 yo girl | 0.5 mg/kg × 2 doses | 6 weeks | Improved pain & mobility | Severe hypocalcemia & hypophosphatemia | Severe hypercalcemia |

|

| ||||||

| Fibrous dysplasia | ||||||

| 47, 48 | 9 yo boy | 1–1.5 mg/kg monthly | 7 months | Decreased tumor expansion & pain | Mild hypophosphatemia | Severe hypercalcemia |

|

| ||||||

| Central giant cell granuloma | ||||||

| 49 | 9 yo girl | 120 mg monthly | 18 months | Decreased tumor size & tooth mobility, improved radiodensity | None | Unknown |

|

| ||||||

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | ||||||

| 50 | 8 & 11 yo boys | 70 mg/m2 monthly | ongoing | Cyst partial regression, improved pain | Mild hypocalcemia (1 patient) | Unknown |

| 51 | 5 yo boy | 1.2–1.6 mg/kg monthly | 12 months | Cyst regression, healed fracture, improved pain | None | Unknown |

|

| ||||||

| Cerebral palsy | ||||||

| 71 | 10 children age 5–17 | 10 mg | one-time dose | n/a | None | Unknown |

& = and, yo = years old, mo = months old, mg = milligrams, kg = kilograms, m2 = meters squared, BMD = bone mineral density, n/a = not applicable

Clinical improvement occurred in the setting of concomitant denosumab treatment and 4 limb rodding surgery.

Developed 2 months following 2 monthly doses (personal communication, Leanne Ward).

Giant Cell Tumors

Giant cell tumor of bone is an uncommon, locally aggressive neoplasm which may rarely metastasize. Tumors are composed of distinctive, multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells and proliferative stromal cells. These abnormal stromal cells highly express RANKL, leading to the hypothesis that RANKL is responsible for giant cell recruitment and ultimately bone destruction and tumor expansion [30]. Management typically involves surgical resection, with systemic therapy reserved for patients with tumors that cannot be fully removed [31]. Denosumab has been studied in a large open label phase 2 trial, with a study population that included ten adolescents confirmed to have closed epiphyses on radiographs [32 33](Table 1). Denosumab prevented tumor progression in 163/169 patients with unresectable disease, and prevented or decreased surgical morbidity in the majority of patients with resectable tumors. Common adverse events included hypophosphatemia (affecting 3% of patients), back, and extremity pain. Denosumab was subsequently approved for treatment of giant cell tumors in adults and skeletally mature adolescents, and is the only medication currently labeled for this indication [25].

Additional reports in two children support the efficacy of denosumab, with both cases demonstrating improvement in giant cell tumor expansion and bone pain [34–37](Table 1). Within several months of denosumab discontinuation both children developed an acute rebound in bone turnover, which was accompanied by severe and life-threatening hypercalcemia necessitating hospitalization and bisphosphonate treatment. This phenomenon, discussed in detail in a later section, has been observed in other children treated with denosumab, and is an important safety concern which appears to be principally associated with pediatric use.

Additional Pediatric-Relevant Conditions

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is the most frequent form of primary osteoporosis in children. Common types result from autosomal dominant COL1A1/1A2 mutations leading to defects in type 1 collagen, while rarer forms result from autosomal recessive mutations in genes responsible for collagen processing or osteoblast function [38]. Bisphosphonates improve bone density, pain, and mobility in OI, and are frequently prescribed for patients with moderate to severe forms [39]. Type 6 OI, due to SERPINF1 mutations, is autosomal recessive with distinct histologic features including prominent unmineralized osteoid, and a typically poor response to bisphosphonates [40]. Semler and Hoyer-Kuhn et al reported 4 boys with type 6 OI treated with a 2-year course of denosumab [41 42]. Patients were initially given 1 mg/kg every 12 weeks, which resulted in a rapid decline in bone turnover markers with each dose, and return to pre-treatment levels after 6–8 weeks. Based on this observation, the dosing interval was shortened to maintain continuous suppression of bone resorption. Children showed a modest increase in BMD, and appeared to tolerate therapy with the development of mild, asymptomatic hypocalcemia in only one patient.

A 23-month old boy with type 6 OI was treated by another group using a similar regimen, however this child had a persistent decline in BMD and continued to fracture over a 12-month treatment period [43], After undergoing four limb rodding surgery to correct severe deformity he developed a significant increase in BMD and improved mobility while on denosumab. Rebound hypercalcemia was observed 2 months following two-monthly denosumab doses; anti-denosumab antibodies were found to be negative. Denosumab was discontinued and pamidronate was given to treat the hypercalcemia, which resolved after a single dose (personal communication, Leanne Ward). Interestingly, a post-treatment biopsy 3 months after the final dose showed persistent unmineralized osteoid and an increased number of osteoclasts compared to pre-treatment.

Hoyer-Kuhn et al reported an open-label study of 10 children with various types of classical OI treated with denosumab for 12 months [44]. Patients were given 1 mg/kg every 3 months, and showed a modest increase in lumbar spine BMD and no improvement in pain or mobility over the treatment period. Effects on mineral metabolism were detectable but mild, including asymptomatic hypocalcemia while on-treatment in one child. Interestingly, mild asymptomatic hypercalcemia was noted in several patients during the trial period just prior to the fourth dose of denosumab. Taken together, these results support that further studies of denosumab in children with OI are warranted, in particular to determine the optimal dose and frequency necessary to maintain consistent osteoclast inhibition.

Juvenile Paget’s Disease

Juvenile Paget’s disease (JPD) is a rare disorder resulting from inactivating mutations in TNFRSF11B, which encodes OPG [45]. Unopposed activation of RANK signaling results in increased osteoclast activity, leading to fractures, deformities, and bone pain. Management includes anti-resorptives, and denosumab is an intuitive treatment given its selective inhibition of the RANK pathway. Grasemann et al report an 8-year-old girl with JPD refractory to bisphosphonates, who was given denosumab 0.5 mg with rapid and dramatic improvement in bone turnover, pain, and mobility [46]. Denosumab was associated with severe and life-threatening disturbances in mineral metabolism, including hypocalcemia requiring hospitalization and intravenous calcium, as well as rebound hypercalcemia seven weeks after denosumab discontinuation. Despite her dramatic therapeutic response, denosumab was discontinued due to safety concerns. While the potential for denosumab as a targeted therapy for JPD is promising, further research into its effects on mineral homeostasis is needed to determine if and how these safety issues can be mitigated. In the interim, denosumab should be used with extreme caution in children with JPD.

Other Benign Osseous Lesions

Based in part on its efficacy in giant cell tumors, denosumab has been investigated as a potential treatment for other benign fibro-osseous lesions affecting children and adolescents, including fibrous dysplasia [47 48], central giant cell granuloma [49], and spinal aneurysmal bone cysts [50 51]. The pediatric literature is currently limited to case reports and small series, all of which report beneficial effects on lesion growth and associated bone pain. Patients received monthly high dose treatment adapted from the Xgeva regimen, which resulted in frequent abnormalities in mineral metabolism. These included mild to moderate hypocalcemia in several patients, and severe rebound hypercalcemia in the fibrous dysplasia patient. Similar to studies in giant cell tumors, these reports highlight denosumab’s potential therapeutic use for skeletal neoplasms, as well as the need to better understand its metabolic effects, in particular for children receiving frequent, high dose therapy.

Safety and Tolerability of Denosumab in Adults and Children

Effects on Bone Turnover, Modeling, and Remodeling

Denosumab has powerful inhibitory effects on bone turnover. In phase 3 trials, bone turnover markers of denosumab-treated subjects were consistently lower than placebo- and bisphosphonate-treated subjects [12 13 15 16 19 20 22–24]. Histomorphometry studies likewise showed potent, sustained inhibition of bone turnover, while maintaining normal bone microarchitecture and without adverse effects on mineralization [16]. Bone turnover suppression may have unique consequences for the growing skeleton, which relies on bone modeling to maintain shape and linear growth. Anti-resorptive treatment with bisphosphonates does not appear to impair growth with typical use [52–54], although subtle modeling defects of uncertain consequence may persist after treatment discontinuation [55]. Although these findings are reassuring, they should not be generalized to denosumab, which is a far more potent inhibitor of bone resorption. Pre-clinical studies of denosumab treatment in rodents and primates demonstrated significant inhibitory effects on linear growth and tooth eruption [21 25 56]. While clinical data is limited, several series have reported continued linear growth during denosumab treatment [34 36 37 42 44 48 57]. Histologic evaluation in a child with fibrous dysplasia demonstrated continued epiphyseal activity both during and after denosumab treatment, providing further evidence that denosumab does not appear to adversely affect growth in the clinical setting [48].

Osteonecrosis of the jaw is a rare complication of denosumab and other anti-resorptives, particularly in patients receiving long-term therapy with chronic suppression of bone turnover. A recent metanalysis of patients receiving anti-resorptives for cancer treatment showed a 1.7% risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with monthly denosumab treatment, which was slightly higher than that 1.1% risk associated with intravenous bisphosphonates [58]. Osteonecrosis of the jaw is even rarer in the setting of osteoporosis treatment [59]. To date there have been no reported cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw in children.

Osteoclasts have important roles in microdamage repair and bone healing. Atypical femoral fractures are a rare complication of anti-resorptives and have been reported in a small number of patients receiving denosumab [60]; however ongoing surveillance is needed to determine a clear association. Denosumab does not appear to impair fracture healing in animal models [61]. While there is little clinical data available, denosumab demonstrated no negative effects on fracture healing in the FREEDOM trial, regardless of the timing of administration [12]. No negative effects on healing have been reported in pediatric patients for whom fracture data is available [47 51].

Bone Turnover Rebound and Post-Discontinuation Effects

Unlike bisphosphonates, which incorporate into hydroxyapatite and have long terminal half-lives, the therapeutic effects of denosumab are rapidly reversed after treatment. In post-menopausal women, denosumab discontinuation resulted in a rebound of both markers of bone resorption (C-telopeptide) and formation (procollagen-1 propeptide) to levels 60 and 40% above pre-treatment levels, respectively, and remained elevated for approximately two years [62]. A similar phenomenon of bone turnover rebound has been observed in pediatric patients, and while information is limited given the small patient numbers, key differences from adults are emerging. Bone turnover rebound in children appears to be more vigorous, of shorter duration, and more commonly associated with hypercalcemia. For example, in the child treated for fibrous dysplasia, serum C-telopeptide rebounded to 250% above the pre-denosumab baseline, necessitating bisphosphonate treatment for hypercalcemia; C-telopeptide then returned to baseline after 5 months. While hypercalcemia post-discontinuation of denosumab is described in one published report of an adult treated with long-term denosumab therapy [63], 5 cases have been reported in the much more limited pediatric literature (Table 1). This may be related to the higher baseline bone turnover in children, which could result in a proportionately greater rebound post-discontinuation. Rebound may also be especially affected by the presence of high bone turnover disorders, which disproportionately affect the population of children who have been treated with denosumab in reports to date.

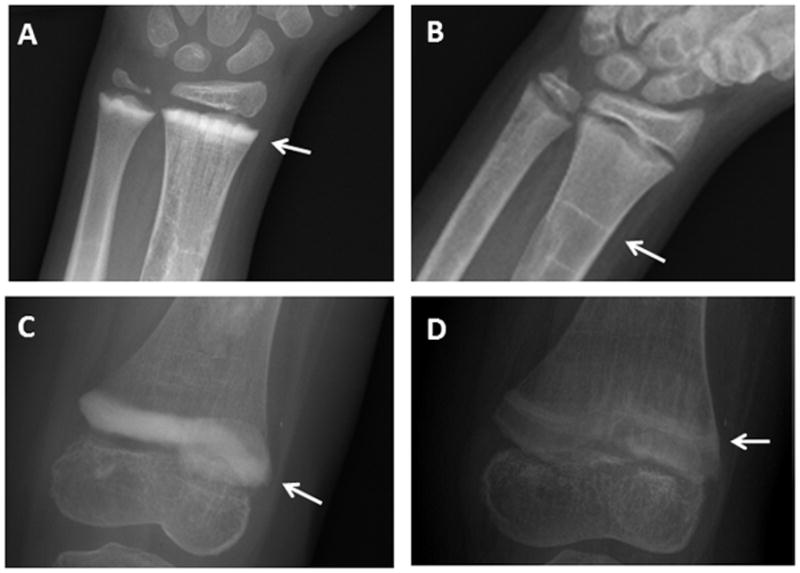

Differential action of anti-resorptives on the growing skeleton may also contribute to the prodigious bone turnover rebound in children. Because the characteristic uncoupling of the bone modeling cycle allows for selective inhibition of resorption with relative sparing of bone formation, anti-resorptives are expected to have more potent effects in growing children compared to adults [55 64]. In children bisphosphonates lead to temporary inhibition of epiphyseal activity with each dose, resulting in the formation of sclerotic metaphyseal bands on radiographs, likely related to retained calcified cartilage [65 66]. A similar phenomenon occurs in children treated with denosumab, with dense sclerotic bands that ultimately fade after denosumab discontinuation [37 48 57](Fig 2). Release of mineral from these bands following completion of therapy is a potential contributor to post-discontinuation hypercalcemia.

Figure 2. Sclerotic metaphyseal bands associated with denosumab treatment.

Radiographs from a child with fibrous dysplasia treated with 6 doses of monthly denosumab show the development of sclerotic bands (white arrows) at the wrist (panel A) and knee (panel C). After discontinuing treatment time the bands have become less dense in appearance over time (panel B, 4-years post-treatment and panel D, one-year post-treatment), and have migrated proximally with linear growth.

Bone turnover reversibility after denosumab discontinuation also results in rapid loss of its therapeutic effects. Adult patients who discontinued denosumab during the FREEDOM trial lost the bone density gained during treatment over a one-year period [67]. This BMD loss did not appear to be associated with an increased fracture risk; however, in the post-marketing period reports have emerged of spontaneous single or multiple vertebral fractures arising during the discontinuation period in post-menopausal [68–70] and breast cancer patients [71]. For this reason, some have proposed that patients receiving denosumab should be given pre- and/or post-treatment with bisphosphonates to mitigate these effects [71]. The rapid reversibility of denosumab effects should also be considered in clinical decision-making. Patients with a history of non-adherence may rapidly lose therapeutic effects if doses are missed or given late, and may not be optimal candidates for denosumab [72]. Conversely, reversibility may be an attractive feature in treatment of children with acquired skeletal disorders that carry the potential for full recovery.

Loss of denosumab effects post-discontinuation also has implications for treatment of giant cell tumors and other osseous lesions. While little has been published about tumor recurrence post-treatment, there are case reports of increased lesion growth after denosumab discontinuation in patients with giant cell tumor [73] and fibrous dysplasia [48]. This suggests the action of denosumab in osseous lesions may be cytostatic rather than cytotoxic, and long-term therapy may be required to maintain therapeutic efficacy.

Other Safety Issues

Denosumab has been studied in adults with chronic kidney disease in a phase 1 study of a single 60 mg injection [74]. Renal impairment did not appear to affect the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of denosumab, however hypocalcemia was seen in 30% of patients with severe renal failure and those receiving dialysis, suggesting denosumab should be used cautiously with judicious monitoring of calcium in this population.

In addition to its role in bone metabolism, RANKL is expressed by immune cells including activated T lymphocytes, B cells, and dendritic cells [56]. RANKL and RANK-deficient mice show immune abnormalities, including absent lymph nodes and thymic changes [56]. In the FREEDOM study the overall incidence of infections was low and similar between denosumab and placebo-treated groups, however there was a slightly higher incidence of skin infections in denosumab-treated subjects [12]. These findings were not replicated in subsequent trials, and ad hoc sub analyses showed heterogeneous etiologies for these events with no clear clinical pattern [75]. While these data are reassuring, further investigation is warranted to determine denosumab effect on immune function, particularly in immunocompromised children.

RANKL is also highly expressed in mammary tissue. In RANKL and RANK-deficient mice, mammary glands appear to develop normally during sexual maturation; however, lobuloalveolar structures fail to form during pregnancy due to apoptosis and impaired proliferation of mammary epithelium [76]. It is unknown if denosumab treatment in pre-pubertal and pubertal girls will impact breast development, however this endpoint should be monitored in future pediatric studies.

Conclusions

Denosumab is a promising anti-resorptive that offers the potential for targeted intervention in children with disorders affecting the RANKL pathway. The reversibility of denosumab effects represents a key difference from bisphosphonates, and is an important consideration in clinical decision-making. Important safety concerns related to bone turnover rebound and mineral homeostasis impact use of denosumab in children, and research is needed to determine if and how these effects can be mitigated. At present, denosumab in children use should be limited to clinical trials and for compassionate use in patients with significantly impaired quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Alison Boyce declares no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

•Of importance

••Of major importance

- 1.Seeman E. Bone modeling and remodeling. Critical reviews in eukaryotic gene expression. 2009;19(3):219–33. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i3.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gosman JH, Stout SD, Larsen CS. Skeletal biology over the life span: a view from the surfaces. American journal of physical anthropology. 2011;146(Suppl 53):86–98. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21612. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogler W, Ward L. Osteoporosis in Children with Chronic Disease. Endocrine development. 2015;28:176–95. doi: 10.1159/000381045. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovacic N, Croucher PI, McDonald MM. Signaling between tumor cells and the host bone marrow microenvironment. Calcified tissue international. 2014;94(1):125–39. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9794-7. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93(2):165–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu H, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor family member RANK mediates osteoclast differentiation and activation induced by osteoprotegerin ligand. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(7):3540–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, et al. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89(2):309–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofbauer LC, Schoppet M. Clinical implications of the osteoprotegerin/RANKL/RANK system for bone and vascular diseases. Jama. 2004;292(4):490–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.490. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutjandra L, Rodriguez RD, Doshi S, et al. Population pharmacokinetic meta-analysis of denosumab in healthy subjects and postmenopausal women with osteopenia or osteoporosis. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2011;50(12):793–807. doi: 10.2165/11594240-000000000-00000. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibiansky L, Sutjandra L, Doshi S, et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of denosumab in patients with bone metastases from solid tumours. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2012;51(4):247–60. doi: 10.2165/11598090-000000000-00000. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng S, Gaitonde P, Andrew MA, Gibbs MA, Lesko LJ, Schmidt S. Model-based assessment of dosing strategies in children for monoclonal antibodies exhibiting target-mediated drug disposition. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology. 2014;3:e138. doi: 10.1038/psp.2014.38. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••12.Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(8):756–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. [published Online First: Epub Date]| The pivotal FREEDOM study was the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial of denosumab to demonstrate a decrease in vertebral and non-vertebral fractures in adults with osteoporosis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura T, Matsumoto T, Sugimoto T, et al. Clinical Trials Express: fracture risk reduction with denosumab in Japanese postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis: denosumab fracture intervention randomized placebo controlled trial (DIRECT) The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99(7):2599–607. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4175. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;93(6):2149–57. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2814. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JP, Prince RL, Deal C, et al. Comparison of the Effect of Denosumab and Alendronate on Bone Mineral Density and Biochemical Markers of Bone Turnover in Postmenopausal Women With Low Bone Mass: A Randomized, Blinded, Phase 3 Trial. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2009:1–34. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080910. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendler DL, Roux C, Benhamou CL, et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women transitioning from alendronate therapy. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2010;25(1):72–81. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090716. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freemantle N, Satram-Hoang S, Tang ET, et al. Final results of the DAPS (Denosumab Adherence Preference Satisfaction) study: a 24-month, randomized, crossover comparison with alendronate in postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2012;23(1):317–26. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1780-1. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papapoulos S, Lippuner K, Roux C, et al. The effect of 8 or 5 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the FREEDOM Extension study. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2015;26(12):2773–83. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3234-7. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MR, Egerdie B, Hernandez Toriz N, et al. Denosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(8):745–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809003. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis GK, Bone HG, Chlebowski R, et al. Randomized trial of denosumab in patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for nonmetastatic breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(30):4875–82. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.16.3832. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prolia [package insert] Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body JJ, et al. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(35):5132–9. doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.29.7101. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M, et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet. 2011;377(9768):813–22. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62344-6. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry DH, Costa L, Goldwasser F, et al. Randomized, double-blind study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced cancer (excluding breast and prostate cancer) or multiple myeloma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(9):1125–32. doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.31.3304. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xgeva [package insert] Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Body JJ, Bone HG, de Boer RH, et al. Hypocalcaemia in patients with metastatic bone disease treated with denosumab. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2015;51(13):1812–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.016. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu MI, Glezerman IG, Leboulleux S, et al. Denosumab for treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99(9):3144–52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1001. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diel IJ, Body JJ, Stopeck AT, et al. The role of denosumab in the prevention of hypercalcaemia of malignancy in cancer patients with metastatic bone disease. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2015;51(11):1467–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.04.017. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shroff R, Beringer O, Rao K, Hofbauer LC, Schulz A. Denosumab for post-transplantation hypercalcemia in osteopetrosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(18):1766–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1206193. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu PF, Tang JY, Li KH. RANK pathway in giant cell tumor of bone: pathogenesis and therapeutic aspects. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2015;36(2):495–501. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3094-y. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Heijden L, Dijkstra PD, van de Sande MA, et al. The clinical approach toward giant cell tumor of bone. The oncologist. 2014;19(5):550–61. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0432. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••32.Chawla S, Henshaw R, Seeger L, et al. Safety and efficacy of denosumab for adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumour of bone: interim analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, phase 2 study. The lancet oncology. 2013;14(9):901–8. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70277-8. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. This open-label study in giant cell tumors included adults and ten skeletally mature adolescents, and demonstrated improvement in tumor progression and skeletal morbidity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin-Broto J, Cleeland CS, Glare PA, et al. Effects of denosumab on pain and analgesic use in giant cell tumor of bone: interim results from a phase II study. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2014;53(9):1173–9. doi: 10.3109/0284186x.2014.910313. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karras NA, Polgreen LE, Ogilvie C, Manivel JC, Skubitz KM, Lipsitz E. Denosumab treatment of metastatic giant-cell tumor of bone in a 10-year-old girl. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(12):e200–2. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.46.4255. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gossai N, Hilgers MV, Polgreen LE, Greengard EG. Critical hypercalcemia following discontinuation of denosumab therapy for metastatic giant cell tumor of bone. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2015;62(6):1078–80. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25393. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Setsu N, Kobayashi E, Asano N, et al. Severe hypercalcemia following denosumab treatment in a juvenile patient. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 2016;34(1):118–22. doi: 10.1007/s00774-015-0677-z. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi E, Setsu N. Osteosclerosis induced by denosumab. Lancet (London, England) 2015;385(9967):539. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61338-6. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forlino A, Marini JC. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet (London, England) 2016;387(10028):1657–71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00728-x. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marom R, Lee YC, Grafe I, Lee B. Pharmacological and biological therapeutic strategies for osteogenesis imperfecta. American journal of medical genetics Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2016;172(4):367–83. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31532. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glorieux FH, Ward LM, Rauch F, Lalic L, Roughley PJ, Travers R. Osteogenesis imperfecta type VI: a form of brittle bone disease with a mineralization defect. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2002;17(1):30–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.1.30. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Semler O, Netzer C, Hoyer-Kuhn H, Becker J, Eysel P, Schoenau E. First use of the RANKL antibody denosumab in osteogenesis imperfecta type VI. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2012;12(3):183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoyer-Kuhn H, Netzer C, Koerber F, Schoenau E, Semler O. Two years’ experience with denosumab for children with osteogenesis imperfecta type VI. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2014;9:145. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0145-1. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward L, Bardai G, Moffatt P, et al. Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type VI in Individuals from Northern Canada. Calcified tissue international. 2016;98(6):566–72. doi: 10.1007/s00223-016-0110-1. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoyer-Kuhn H, Franklin J, Allo G, et al. Safety and efficacy of denosumab in children with osteogenesis imperfect--a first prospective trial. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2016;16(1):24–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ralston SH. Juvenile Paget’s disease, familial expansile osteolysis and other genetic osteolytic disorders. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology. 2008;22(1):101–11. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.11.005. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grasemann C, Schundeln MM, Hovel M, et al. Effects of RANK-ligand antibody (denosumab) treatment on bone turnover markers in a girl with juvenile Paget’s disease. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98(8):3121–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1143. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyce AM, Chong WH, Yao J, et al. Denosumab treatment for fibrous dysplasia. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27(7):1462–70. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1603. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48•.Wang HD, Boyce AM, Tsai JY, et al. Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on human growth plates. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99(3):891–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3081. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. This study provided histopathologic evidence that denosumab treatment did not appear to adversely effect growth plates in a growing child. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naidu A, Malmquist MP, Denham CA, Schow SR. Management of central giant cell granuloma with subcutaneous denosumab therapy. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2014;72(12):2469–84. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.06.456. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lange T, Stehling C, Frohlich B, et al. Denosumab: a potential new and innovative treatment option for aneurysmal bone cysts. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2013;22(6):1417–22. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2715-7. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pelle DW, Ringler JW, Peacock JD, et al. Targeting receptor-activator of nuclear kappaB ligand in aneurysmal bone cysts: verification of target and therapeutic response. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2014;164(2):139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.005. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeitlin L, Rauch F, Plotkin H, Glorieux FH. Height and weight development during four years of therapy with cyclical intravenous pamidronate in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta types I, III, and IV. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 1):1030–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unal E, Abaci A, Bober E, Buyukgebiz A. Efficacy and safety of oral alendronate treatment in children and adolescents with osteoporosis. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism : JPEM. 2006;19(4):523–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palomo T, Fassier F, Ouellet J, et al. Intravenous Bisphosphonate Therapy of Young Children With Osteogenesis Imperfecta: Skeletal Findings During Follow Up Throughout the Growing Years. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2015;30(12):2150–7. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2567. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rauch F, Cornibert S, Cheung M, Glorieux FH. Long-bone changes after pamidronate discontinuation in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone. 2007;40(4):821–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.020. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, et al. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397(6717):315–23. doi: 10.1038/16852. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoyer-Kuhn H, Semler O, Schoenau E. Effect of denosumab on the growing skeleton in osteogenesis imperfecta. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99(11):3954–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3072. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qi WX, Tang LN, He AN, Yao Y, Shen Z. Risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients receiving denosumab: a meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials. International journal of clinical oncology. 2014;19(2):403–10. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0561-6. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, et al. Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: a systematic review and international consensus. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2015;30(1):3–23. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2405. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Selga J, Nunez JH, Minguell J, Lalanza M, Garrido M. Simultaneous bilateral atypical femoral fracture in a patient receiving denosumab: case report and literature review. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2016;27(2):827–32. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3355-z. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gerstenfeld LC, Sacks DJ, Pelis M, et al. Comparison of effects of the bisphosphonate alendronate versus the RANKL inhibitor denosumab on murine fracture healing. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2009;24(2):196–208. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081113. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, et al. Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96(4):972–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1502. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koldkjaer Solling AS, Harslof T, Kaal A, Rejnmark L, Langdahl B. Hypercalcemia after discontinuation of long-term denosumab treatment. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2016;27(7):2383–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3535-5. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rauch F, Travers R, Plotkin H, Glorieux FH. The effects of intravenous pamidronate on the bone tissue of children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2002;110(9):1293–9. doi: 10.1172/jci15952. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Persijn van Meerten EL, Kroon HM, Papapoulos SE. Epi- and metaphyseal changes in children caused by administration of bisphosphonates. Radiology. 1992;184(1):249–54. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.1.1609087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rauch F, Travers R, Munns C, Glorieux FH. Sclerotic metaphyseal lines in a child treated with pamidronate: histomorphometric analysis. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2004;19(7):1191–3. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.040303. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown JP, Roux C, Torring O, et al. Discontinuation of denosumab and associated fracture incidence: analysis from the Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months (FREEDOM) trial. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2013;28(4):746–52. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1808. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aubry-Rozier B, Gonzalez-Rodriguez E, Stoll D, Lamy O. Severe spontaneous vertebral fractures after denosumab discontinuation: three case reports. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2016;27(5):1923–5. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3380-y. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lamy O, Gonzalez-Rodriguez E, Stoll D, Hans D, Aubry-Rozier B. Severe rebound-associated vertebral fractures after denosumab discontinuation: nine clinical cases report. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2016:jc20163170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3170. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Polyzos SA, Terpos E. Clinical vertebral fractures following denosumab discontinuation. Endocrine. 2016;54(1):271–72. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1030-6. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Popp AW, Zysset PK, Lippuner K. Rebound-associated vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab-from clinic and biomechanics. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2016;27(5):1917–21. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3458-6. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scheinberg MA, Golmia RP, Sallum AM, Pippa MG, Cortada AP, Silva TG. Bone health in cerebral palsy and introduction of a novel therapy. Einstein (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 2015;13(4):555–9. doi: 10.1590/s1679-45082015ao3321. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matcuk GR, Jr, Patel DB, Schein AJ, White EA, Menendez LR. Giant cell tumor: rapid recurrence after cessation of long-term denosumab therapy. Skeletal radiology. 2015;44(7):1027–31. doi: 10.1007/s00256-015-2117-5. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Block GA, Bone HG, Fang L, Lee E, Padhi D. A single-dose study of denosumab in patients with various degrees of renal impairment. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27(7):1471–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1613. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Watts NB, Roux C, Modlin JF, et al. Infections in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with denosumab or placebo: coincidence or causal association? Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2012;23(1):327–37. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1755-2. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fata JE, Kong YY, Li J, et al. The osteoclast differentiation factor osteoprotegerin-ligand is essential for mammary gland development. Cell. 2000;103(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]