Abstract

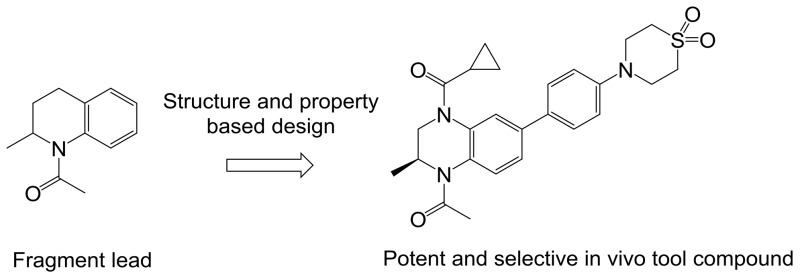

A protein structure-guided drug design approach was employed to develop small molecule inhibitors of the BET family of bromodomains that were distinct from the known (+)-JQ1 scaffold class. These efforts led to the identification of a series of substituted benzopiperazines with structural features that enable interactions with many of the affinity-driving regions of the bromodomain binding site. Lipophilic efficiency was a guiding principle in improving binding affinity alongside drug-like physicochemical properties that are commensurate with oral bioavailability. Derived from this series was tool compound FT001, which displayed potent biochemical and cellular activity, translating to excellent in vivo activity in a mouse xenograft model (MV-4-11).

Keywords: Bromodomains, BET, BRD4

The bromodomain and extra terminal (BET) family of bromodomains consists of BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDT, with each containing tandem bromodomains (BD1 and BD2).1 The BET family of proteins binds to acetylated lysine (KAc) residues on histone proteins and are involved in recruiting transcriptional coactivators to promoter sites, ultimately leading to transcription of genes relevant to oncology and other diseases.2 In doing so, the BET family of bromodomains are classified as “readers” of the specific acetylated marks that are laid down on the histone proteins by other epigenetic enzymes, such as histone acetyltransferases.3

In 2010, two landmark publications described the binding of two selective inhibitors to the KAc binding region of the BET family of bromodomains, namely, (+)-JQ1 and I-BET762.4,5 These inhibitors, and their pharmacological impact in preclinical cancer models, generated enormous excitement and prompted the search for other differentiated BET inhibitor chemotypes. Several examples of differentiated structural classes include I-BET151,6 I-BET726,7 CPI-0610,8 RVX-208,9 PFI-1,10 and ABBV-075.11 Many more structural classes now exist, which have been reviewed extensively elsewhere.12−14 The most advanced inhibitor is RVX-208, which is in Phase 2/3 clinical trials for cardiovascular related disorders.9 For oncology related indications, most inhibitors are in Phase 1/2 clinical trials, with OTX015/MK-8628 demonstrating promising activity in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and lymphoma.14−16

The promising preclinical activity of inhibitors such as (+)-JQ1 led us to initiate our own drug discovery program aimed at identifying novel chemotypes. Our approach to identify novel chemical scaffolds was multipronged, involving high-throughput biochemical screening of an internal collection of compounds as well as de novo structure-based design approaches. With regard to the latter approach, we were intrigued by an early report from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), which demonstrated that fragments reproduced the binding interactions of the KAc and could be crystallized in BRD4 with high resolution, despite having weak binding affinity.17 One such fragment was N-acetyl-2-methyltetrahydroquinoline 1, which was crystallized in BRD2 BD1, and displayed weak inhibition (44% inhibition at 50 μM) (Figure 1).

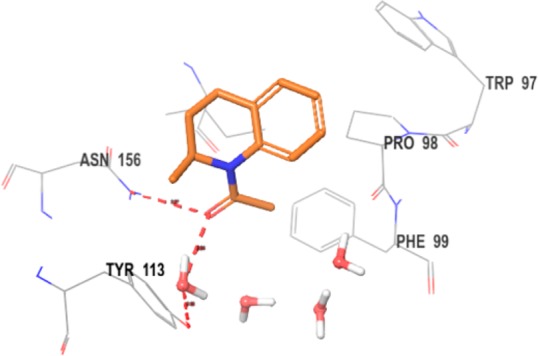

Figure 1.

Cocrystal structure of 1 (2.05 Å) bound to BRD2 BD1 (PDB code: 4A9H, chain A). Key hydrogen bonding interactions are highlighted, with water molecules represented by red and white objects. Residue numbering throughout the Letter is for human BRD4. The Trp-Pro-Phe shelf (WPF) is indicated also.

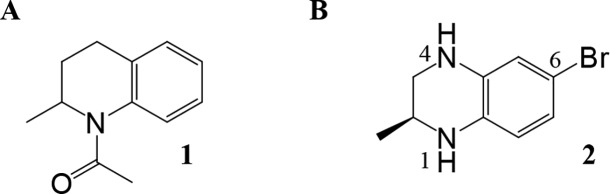

As can be seen from the crystal structure of 1 in BRD2 BD1, the N-acetyl group is an isostere for the KAc group, accepting a hydrogen bond from Asn156 and a bridging water molecule that hydrogen bonds to Tyr113. Interestingly, the methyl group attached to the stereogenic center was selected in the crystal lattice, filling a small lipophilic pocket. Some of these structural features are also present in the BET inhibitor I-BET7267 and the related cAMP response element binding protein (CBP) inhibitor I-CBP112.18 We envisaged that we could maintain these seemingly important interactions and substitute the methylene group in the 4-position of the partially saturated ring system with a nitrogen atom. This change would place a synthetically tractable handle in a position that could enable access to the three residues Trp81-Pro82-Phe83 (WPF shelf), which are judged to be an important affinity-driving interaction.17 In addition, we hypothesized that building toward Trp81 (BRD4 BD1) to form an edge-to-face interaction, with that residue, may also be important for driving affinity. An early BET inhibitor from GSK (I-BET151) similarly fills this space with the benzimidazolone core of the scaffold.6 Modeling suggested substituting off of the 6-position of the benzopiperazine scaffold would allow access to the Trp81 region of the binding site. An important consideration for our lead generation activities was to identify novel and synthetically tractable scaffolds to enable the rapid expansion of SAR at multiple positions of interest using simple, robust and orthogonal chemistries. By moving from the tetrahydroquinoline core in 1 to a 6-bromobenzopiperazine intermediate 2, three synthetic handles (two anilino nitrogens and an aromatic bromine) are available for rapid exploration at the three hypothesized key affinity-driving regions of the binding pocket: WPF shelf, KAc binding region, and edge-to-face interaction with Trp81, respectively (Chart 1). Initial efforts focused on N4 and C6 of the benzopiperazine ring system with a variety of functional groups (Table 1).19

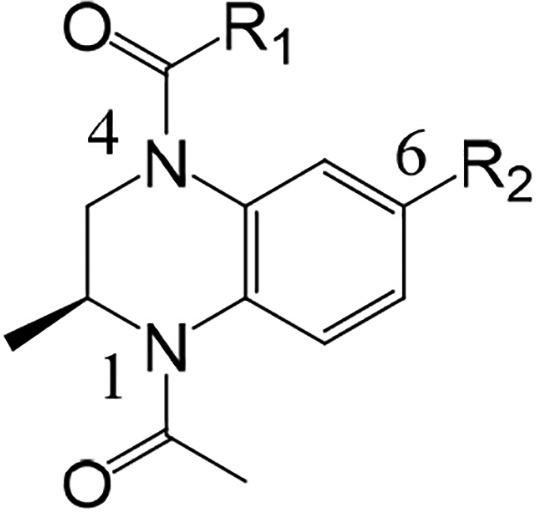

Chart 1. (A) Published17 Fragment N-Acetyl-2-methyltetrahydroquinoline 1; (B) Intermediate 2 with Positions of Substitution Indicated.

Table 1. Initial SAR and Optimization of Potency and Physicochemical Properties for Benzopiperazine Scaffold.

Binding was measured using an AlphaScreen assay technology with the isolated bromodomain. Reported as mean of at least two separate assay runs.

MV-4-11 was used to assess antiproliferative activity in cells. Reported as mean of at least two separate assay runs.

Molecular weight.

Calculated logD value at pH = 7.4.

Ligand efficiency = pIC50(BRD4 BD1)/(#heavy atoms).

Lipophilic efficiency = pIC50(BRD4 BD1) – clogD7.4.

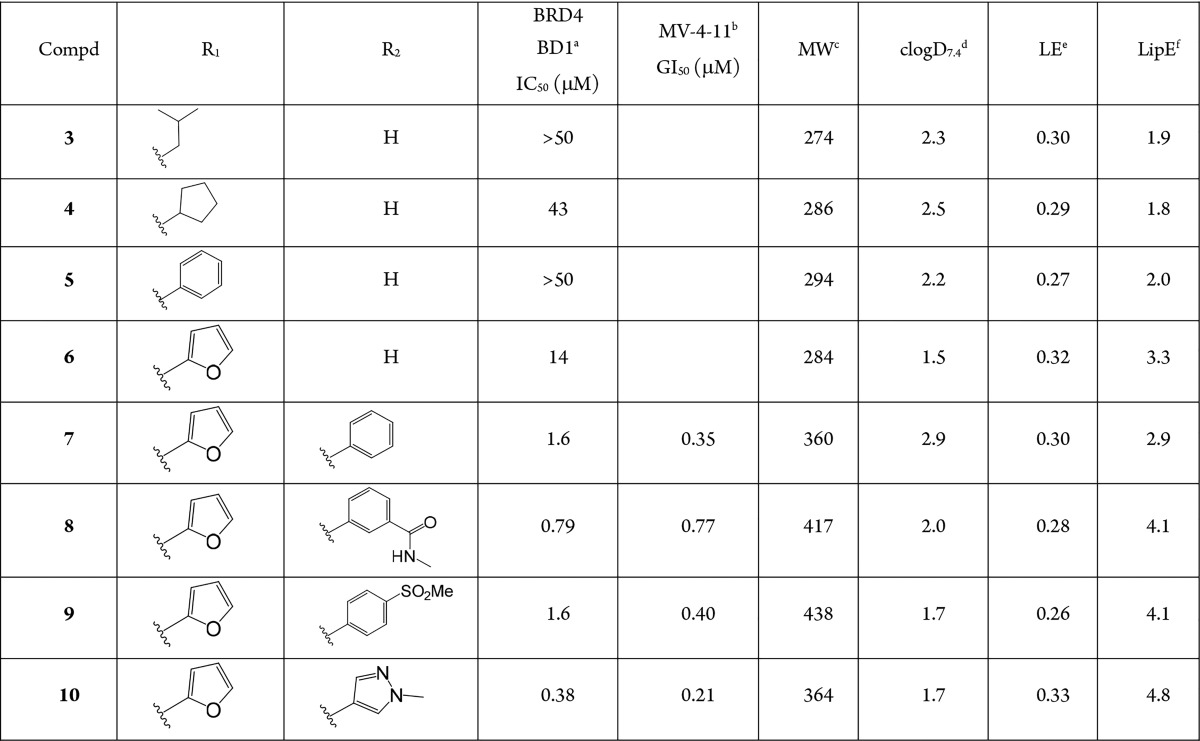

Modeling suggested that alkyl or aryl amides could potentially have the length and vector to reach the WPF shelf, and therefore, compounds 3 and 4 were synthesized, along with several others. These compounds demonstrated weak activity, with ligand efficiency (LE) lower than that reported for 1 (LE = 0.39).17 Similarly, benzamide 5 did not show promising activity. Substantial scanning at the position through parallel chemistry ultimately identified furan 6 with LE and lipophilic efficiency (LipE) approaching that of an interesting lead compound. The addition of a phenyl group at C6 with compound 7 produced an approximate 10-fold improvement in binding affinity for BRD4 BD1, albeit without an improvement in LE or LipE. The addition of polar functionality produced compound 8 with improved LipE. The predicted binding mode of 8, and other compounds from this series, suggested that the carboxamide would be protruding into solvent and not directly involved in interactions with the protein. Therefore, this region of the inhibitor could be useful for introducing functionality to modulate physicochemical properties. This observation rationalizes the significant improvement in LipE for 8. Similarly, sulfone 9 was equivalent in binding affinity and LipE.

With binding affinities now in the submicromolar range with 8, we began profiling the antiproliferative activity in liquid and solid tumor cell lines. In particular, we focused on MV-4-11 (human biphenotypic B myelomonocytic leukemia) as a routine cancer cell line to profile compounds and to benchmark across published BET inhibitors, as it is widely used to investigate this target.20 Gratifyingly, the aforementioned compounds 7–9 all had submicromolar antiproliferative activity in this cell line.

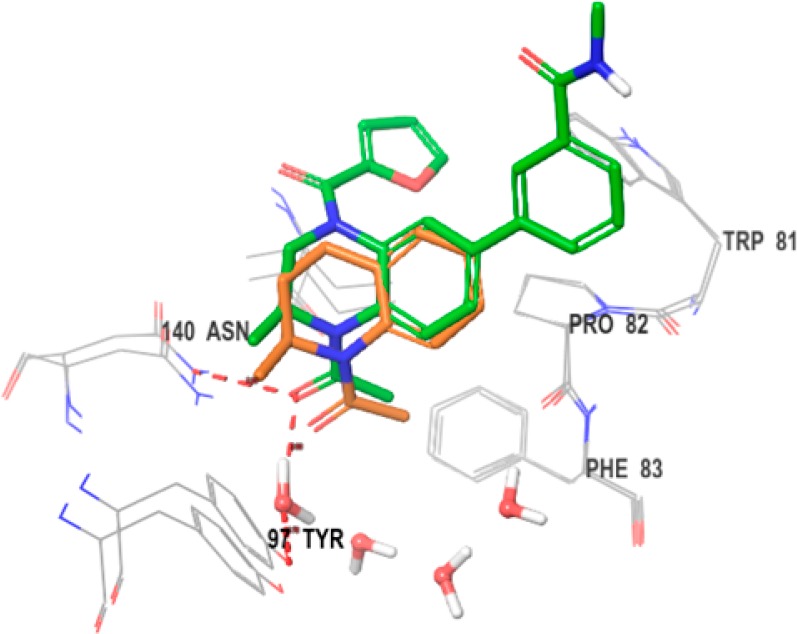

With the identification of 8 and its attractive potency and physicochemical properties, we obtained a cocrystal structure in BRD4 BD1 to enable structure-guided design aimed at improving binding affinity. We obtained a 1.66 Å cocrystal structure, which confirmed the predicted binding mode and demonstrated the intended interaction of the furan amide with the WPF shelf (Figure 2; additional views are available in the Supporting Information). When fragment 1 is overlaid with 8, it appears the elaborated benzopiperazine analogue maintains the KAc interactions, the spatial vector of the methyl group at C2, and the conformation of the partially saturated six-membered ring system, despite the addition of a heteroatom at position four. In addition, as predicted, the carboxamide-bearing phenyl ring at C6 of the benzopiperazine forms an edge-to-face interaction with Trp81 and does indeed extend into the solvent. This confirmed that substitution at the meta and para positions could be useful to tune physicochemical properties.

Figure 2.

Cocrystal structure of 8 (green, 1.66 Å) in BRD4 BD1 (chain B) (PDB code: 5VOM) with an overlay of 1 (orange) (PDB code: 4A9H).

At this stage, we also explored the introduction of several other five- and six-membered aromatic rings at C6, and from the examples prepared, it appeared that both ring sizes were well-tolerated and potent (Table 1).19 The pyrazole 10 appeared to be a potent ring system with improved LipE and was explored further in subsequent compounds.

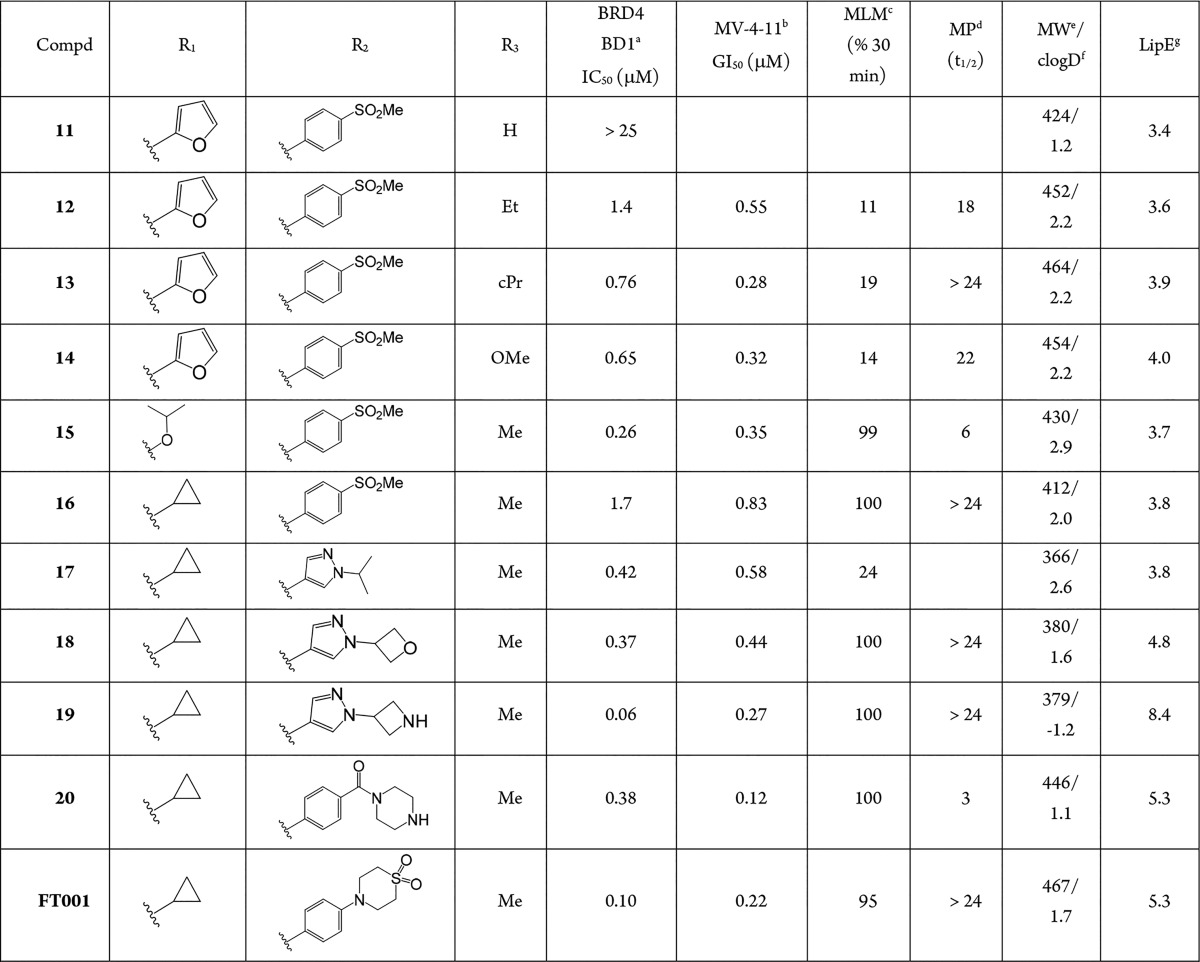

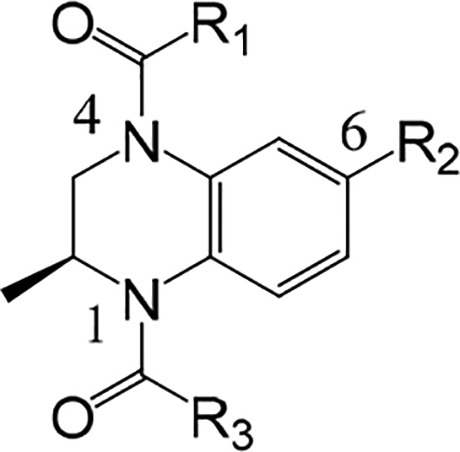

Having identified substituted benzopiperazines as a viable class of BET inhibitors, we turned our attention to optimization of this series with the goal of identifying a tool compound suitable for generating proof-of-concept (POC) in an in vivo study. These efforts focused on SAR development of all three readily functionalized positions (R1, R2, and R3) (Table 2). We first explored the impact of changes on the KAc binding interactions. Initial N-acetyl (R3 = Me) compounds, such as 9, were active, however, removal of the methyl resulted in a significant loss of potency as in 11. Introduction of an additional carbon atom to afford ethyl analogue 12, or a carbamate 14, was essentially equipotent with the methyl analogue 9. Cyclopropyl amide 13 was also well tolerated, but if larger groups were introduced, a significant loss in potency was observed (data not shown).

Table 2. SAR Towards a POC Tool Compound.

Binding was measured using an AlphaScreen assay technology with the isolated bromodomain. Reported as mean of at least two separate assay runs.

MV-4-11 was used to assess antiproliferative activity in cells. Reported as mean of at least two separate assay runs.

Mouse liver microsome stability expressed as percent remaining after 30 min incubation.

Mouse plasma stability expressed as a half-life.

Molecular weight.

Calculated logD value at pH = 7.4.

Lipophilic efficiency = pIC50(BRD4 BD1) – clogD7.4.

At this stage of the program, profiling in vitro ADME properties, such as mouse liver microsome (MLM) stability and mouse plasma (MP) stability, became important as in vivo mouse models were planned. It became apparent with 12 that these two parameters would need further optimization as the compound showed instability in both assays. Modification to a cyclopropyl group in the KAc binding site appeared well-tolerated from a potency perspective for 13, but it still suffered from MLM instability. Similarly, methyl carbamate 14 was equipotent with 13, but was also unstable in MLM.

Next, chemistry was developed to survey SAR across several different functional groups at N4 of the benzopiperazine, including amides, alkyl groups, sulfonamides, carbamates, and ureas. We rapidly identified carbamates as a functional group that was generally more potent, with amides also having significant binding affinity. The urea, alkyl, and sulfonamide functional groups were all significantly weaker or inactive and therefore of lower interest (data not shown).19 An example of a carbamate with good binding affinity was compound 15, which was more potent than its matched pair 9 and significantly more stable in MLM, but unfortunately still suffered from MP instability.

At this point we invested in chemistry to synthesize the opposite enantiomer of 15 to investigate the effect of this stereogenic center at position 2 of the partially saturated ring system. This compound proved to be inactive (data not shown), suggesting that filling the small lipophilic pocket, mentioned above, is key and/or that the epimer at this position has a significant impact on the conformation of the partially saturated ring system and therefore renders it inactive.

Cyclopropyl amides, such as 16, demonstrated moderate potency and, more importantly, stability in MLM and MP. Combining the cyclopropyl amide with the pyrazole 17 afforded an active and lower MW compound, albeit with reduced stability in MLM. Most of the analogues discussed above had very similar LipE values (LipE ≈ 3.9) coupled with instability in MLM. We hypothesized that by lowering the lipophilicity and focusing on improving the LipE we may increase the probability of obtaining compounds with suitable stability in MLM. Holistic analysis of our data (not shown) suggested that targeting a cLogD range between 1 and 2 would increase the likelihood of achieving this goal. We focused our efforts on modification of the solvent-exposed position (R2), which as noted previously is an area where physicochemical properties could be altered without impacting potency significantly.

Altering the substitution on the pyrazole in 17 afforded oxetane 18 with clogD that was lowered by one unit. Compound 18 (LipE = 4.8) maintained activity in both the biochemical and cell-based assays and was stable in MLM and MP. Unfortunately, the oxetane proved to be chemically unstable to acid, and this compound was not progressed further. When the oxetane in 18 was substituted for an azetidine 19, the compound proved to be potent, MLM and MP stable, but we were concerned about the cellular permeability as the clogD was very low (clogD = −1.2). The MV-4-11 potency suggested the compound had cellular permeability, but we felt it important to understand its oral absorption characteristics. Indeed, on oral dosing in mice, negligible plasma exposure was observed (data not shown). Since the basic chemotype in 19 appeared to deliver attractive in vitro properties, we applied this to our design philosophy in conjunction with raising the clogD into the range mentioned above. This afforded a more potent and MLM stable compound 20 compared to previous analogues. However, MP stability was once again an issue. Efforts to build a SAR relationship with MP instability were unsuccessful, and therefore, we were reliant on an empirical process to solve the problem.

Further optimization using focused libraries ultimately produced FT001, which met the desired goals and properties. Compound FT001 possesses sufficient activity in our biochemical (similar activity to (+)-JQ1; see Supporting Information) and cell-based assays and is very stable in MLM and MP. The physicochemical properties are also consistent with properties for achieving oral exposure, and indeed, upon oral dosing in mouse, significant unbound plasma exposure was obtained in a range that is relevant to the cellular activity in MV-4-11 (see Supporting Information). In addition, the compound was screened in a broad panel of bromodomains, including all BET family members, and found to be selective for the BET family of bromodomains (See Supporting Information).

In preparation for in vivo studies, the tolerability of FT001 in athymic nude mice was examined. Upon repeat oral dosing (twice daily) for 5 days, the MTD was estimated to be 12.5 mg/kg. Previous researchers had demonstrated that (+)-JQ1 suppressed the expression of the oncogene MYC both in vitro and in vivo.20 Therefore, we investigated the effects of FT001 in the MV-4-11 cell line and found that FT001 inhibited the expression of MYC in the submicromolar range (IC50 = 0.46 μM). This inhibition was similar to the MV-4-11 antiproliferative activity we previously observed (IC50 = 0.22 μM). When dosed orally at 12.5 mg/kg (single dose) to athymic nude mice bearing MV-4-11 xenografts, FT001 suppressed MYC to a level approximately one-fifth of that observed for the vehicle treated mice (see Supporting Information). Following these promising results, we investigated the effects of FT001 on the tumor growth inhibition in this same xenograft model. Following 20 days of continuous twice daily oral dosing of FT001, the mouse MV-4-11 xenograft model displayed complete tumor growth inhibition (see Supporting Information).

In summary, we have described the discovery of a novel series of benzopiperazines as potent BET inhibitors. An emphasis on synthetic tractability at key positions on the scaffold, combined with parallel synthesis of focused libraries, enabled rapid SAR expansion and identification of optimal binding groups at the WPF shelf, the KAc binding region, and Trp 81 (BRD4 BD1). This led to the discovery of FT001, which had the best balance of potency and in vitro and in vivo properties, enabling it to be used as a tool to develop POC. Compound FT001 has potent antiproliferative effects against MV-4-11 and demonstrates significant MYC mRNA suppression both in vitro and in vivo. Upon daily oral dosing of FT001, complete tumor growth inhibition was observed at well-tolerated doses. Further optimization of FT001, together with key data will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank Goss Kauffman for helpful technical contributions to synthetic chemistry. We also acknowledge Hien Diep for in vitro ADME support. Finally, we acknowledge Mark J. Tebbe and Kenneth W. Bair for helpful discussions.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- MTD

maximum tolerated dose

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- PO

Latin for “to be taken orally”

- POC

proof-of-concept

- SAR

structure–activity Relationship

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00191.

Synthetic procedures, compound characterization, assay details, PK, PD, and efficacy study description of compound FT001 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wu S.-Y.; Chiang C.-M. The Double Bromodomain-Containing Chromatin Adaptor Brd4 and Transcriptional Regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282 (18), 13141–13145. 10.1074/jbc.R700001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L.-L.; Tian M.; Li X.; Li J.-J.; Huang J.; Ouyang L.; Zhang Y.; Liu B. Inhibition of BET Bromodomains as a Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer Drug Discovery. Oncotarget 2015, 6 (8), 5501–5516. 10.18632/oncotarget.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrowsmith C. H.; Bountra C.; Fish P. V.; Lee K.; Schapira M. Epigenetic Protein Families: A New Frontier for Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2012, 11 (5), 384–400. 10.1038/nrd3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodeme E.; Jeffrey K. L.; Schaefer U.; Beinke S.; Dewell S.; Chung C.-W.; Chandwani R.; Marazzi I.; Wilson P.; Coste H.; White J.; Kirilovsky J.; Rice C. M.; Lora J. M.; Prinjha R. K.; Lee K.; Tarakhovsky A. Suppression of Inflammation by a Synthetic Histone Mimic. Nature 2010, 468 (7327), 1119–1123. 10.1038/nature09589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P.; Qi J.; Picaud S.; Shen Y.; Smith W. B.; Fedorov O.; Morse E. M.; Keates T.; Hickman T. T.; Felletar I.; Philpott M.; Munro S.; McKeown M. R.; Wang Y.; Christie A. L.; West N.; Cameron M. J.; Schwartz B.; Heightman T. D.; La Thangue N.; French C. A.; Wiest O.; Kung A. L.; Knapp S.; Bradner J. E. Selective Inhibition of BET Bromodomains. Nature 2010, 468 (7327), 1067–1073. 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal J.; Lamotte Y.; Donche F.; Bouillot A.; Mirguet O.; Gellibert F.; Nicodeme E.; Krysa G.; Kirilovsky J.; Beinke S.; McCleary S.; Rioja I.; Bamborough P.; Chung C.-W.; Gordon L.; Lewis T.; Walker A. L.; Cutler L.; Lugo D.; Wilson D. M.; Witherington J.; Lee K.; Prinjha R. K. Identification of a Novel Series of BET Family Bromodomain Inhibitors: Binding Mode and Profile of I-BET151 (GSK1210151A). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22 (8), 2968–2972. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosmini R.; Nguyen V. L.; Toum J.; Simon C.; Brusq J.-M. G.; Krysa G.; Mirguet O.; Riou-Eymard A. M.; Boursier E. V.; Trottet L.; Bamborough P.; Clark H.; Chung C.; Cutler L.; Demont E. H.; Kaur R.; Lewis A. J.; Schilling M. B.; Soden P. E.; Taylor S.; Walker A. L.; Walker M. D.; Prinjha R. K.; Nicodème E. The Discovery of I-BET726 (GSK1324726A), a Potent Tetrahydroquinoline ApoA1 up-Regulator and Selective BET Bromodomain Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57 (19), 8111–8131. 10.1021/jm5010539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht B. K.; Gehling V. S.; Hewitt M. C.; Vaswani R. G.; Côté A.; Leblanc Y.; Nasveschuk C. G.; Bellon S.; Bergeron L.; Campbell R.; Cantone N.; Cooper M. R.; Cummings R. T.; Jayaram H.; Joshi S.; Mertz J. A.; Neiss A.; Normant E.; O’Meara M.; Pardo E.; Poy F.; Sandy P.; Supko J.; Sims R. J.; Harmange J.-C.; Taylor A. M.; Audia J. E. Identification of a Benzoisoxazoloazepine Inhibitor (CPI-0610) of the Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (BET) Family as a Candidate for Human Clinical Trials. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (4), 1330–1339. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picaud S.; Wells C.; Felletar I.; Brotherton D.; Martin S.; Savitsky P.; Diez-Dacal B.; Philpott M.; Bountra C.; Lingard H.; Fedorov O.; Müller S.; Brennan P. E.; Knapp S.; Filippakopoulos P. RVX-208, an Inhibitor of BET Transcriptional Regulators with Selectivity for the Second Bromodomain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110 (49), 19754–19759. 10.1073/pnas.1310658110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picaud S.; Da Costa D.; Thanasopoulou A.; Filippakopoulos P.; Fish P. V.; Philpott M.; Fedorov O.; Brennan P.; Bunnage M. E.; Owen D. R.; Bradner J. E.; Taniere P.; O’Sullivan B.; Müller S.; Schwaller J.; Stankovic T.; Knapp S. PFI-1, a Highly Selective Protein Interaction Inhibitor, Targeting BET Bromodomains. Cancer Res. 2013, 73 (11), 3336–3346. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarthy A.; Li L.; Albert D. H.; Lin X.; Scott W.; Faivre E.; Bui M. H.; Huang X.; Wilcox D. M.; Magoc T.; Buchanan F. G.; Tapang P.; Sheppard G. S.; Wang L.; Fidanze S. D.; Pratt J.; Liu D.; Hasvold L.; Hessler P.; Uziel T.; Lam L.; Rajaraman G.; Fang G.; Elmore S. W.; Rosenberg S. H.; McDaniel K.; Kati W.; Shen Y. Abstract 4718: ABBV-075, a Novel BET Family Bromodomain Inhibitor, Represents a Promising Therapeutic Agent for a Broad Spectrum of Cancer Indications. Cancer Res. 2016, 76 (14 Supplement), 4718. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2016-4718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri E.; Petosa C.; McKenna C. E. Bromodomains: Structure, Function and Pharmacology of Inhibition. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 106, 1–18. 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero F. A.; Taylor A. M.; Crawford T. D.; Tsui V.; Côté A.; Magnuson S. Disrupting Acetyl-Lysine Recognition: Progress in the Development of Bromodomain Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (4), 1271–1298. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Wang P.; Chen H.; Wold E. A.; Tian B.; Brasier A. R.; Zhou J. Drug Discovery Targeting Bromodomain-Containing Protein 4. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (11), 4533–4558. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoulou N. H.; Tomkinson N. C.; Prinjha R. K.; Humphreys P. G. Clinical Progress and Pharmacology of Small Molecule Bromodomain Inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 33, 58–66. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abedin S. M.; Boddy C. S.; Munshi H. G. BET Inhibitors in the Treatment of Hematologic Malignancies: Current Insights and Future Prospects. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 5943–5953. 10.2147/OTT.S100515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C.-W.; Dean A. W.; Woolven J. M.; Bamborough P. Fragment-Based Discovery of Bromodomain Inhibitors Part 1: Inhibitor Binding Modes and Implications for Lead Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55 (2), 576–586. 10.1021/jm201320w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp T. A.; Tallant C.; Rogers C.; Fedorov O.; Brennan P. E.; Müller S.; Knapp S.; Bracher F. Development of Selective CBP/P300 Benzoxazepine Bromodomain Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (19), 8889–8912. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair K. W.; Herbertz T.; Kauffman G. S.; Kayser-Bricker K. J.; Luke G. P.; Martin M. W.; Millan D. S.; Schiller S. E. R.; Talbot A. C.; Tebbe M. J.. WO2015/074081, 21 May 2015.

- Mertz J. A.; Conery A. R.; Bryant B. M.; Sandy P.; Balasubramanian S.; Mele D. A.; Bergeron L.; Sims R. J. Targeting MYC Dependence in Cancer by Inhibiting BET Bromodomains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108 (40), 16669–16674. 10.1073/pnas.1108190108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.