Abstract

Phosphatidylionsitol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a substrate of phospholipase C, has recently been recognized to regulate membrane-associated proteins and act as a signal molecule in phospholipase C-linked Gq-coupled receptor (GqPCR) pathways. However, it is not known whether PIP2 depletion induced by GqPCRs can act as receptor-specific signals in native cells. We investigated this issue in cardiomyocytes where PIP2-dependent ion channels, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) and inwardly rectifying background K+ (IRK) channels, and various GqPCRs are present. The GIRK current was recorded by using the patch-clamp technique during the application of 10 μM acetylcholine. The extent of receptor-mediated inhibition was estimated as the current decrease over 4 min while taking the GIRK current (IGIRK) value during a previous stimulation as the control. Each GqPCR agonist inhibited IGIRK with different potencies and kinetics. The extents of inhibition induced by phenylephrine, angiotensin II, endothelin-1, prostaglandin F2α, and bradykinin at supramaximal concentrations were (mean ± SE) 32.1 ± 0.6%, 21.9 ± 1.4%, 86.4 ± 1.6%, 63.7 ± 4.9%, and 5.7 ± 1.9%, respectively. GqPCR-induced inhibitions of IGIRK were not affected by protein kinase C inhibitor (calphostin C) but potentiated and became irreversible when the replenishment of PIP2 was blocked by wortmannin (phosphatidylinositol kinase inhibitor). Loading the cells with PIP2 significantly reduced endothelin-1 and prostaglandin F2α-induced inhibition of IGIRK. On the contrary, GqPCR-mediated inhibitions of inwardly rectifying background K+ currents were observed only when GqPCR agonists were applied with wortmannin, and the effects were not parallel with those on IGIRK. These results indicate that GqPCR-induced inhibition of ion channels by means of PIP2 depletion occurs in a receptor-specific manner.

Keywords: phospholipase C, cardiac myocyte, phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase, Gq-coupled receptor, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels

Because the role of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) in the regulation of ion channel gating has been recognized for various ion channels, such as the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (1), the inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor Ca2+ channel (2), mammalian rod cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (3), and several inwardly rectifying K+ channels (1, 4, 5), the question arises whether changes in PIP2 concentrations induced by normal signaling mechanisms can exert such a role. The levels of PIP2 can be changed by the enzymes involved in phosphoinositide metabolism, such as phosphoinositide kinases and phosphatase, and the enzyme that uses PIP2 as a substrate. Phospholipase C (PLC) hydrolyzes PIP2 into diacylglycerol (DAG) and IP3, thus causing the depletion of PIP2. Because in normal signaling pathways PLC can be activated by the activation of Gq protein-coupled receptors (GqPCRs), this question is about whether ion channels can be regulated by PIP2 depletion induced by GqPCR activation. It has been proved to be true for the GqPCR-mediated inhibition of various K+ currents. For example, α1-adrenergic receptor stimulation causes the inhibition of G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) currents in atrial myocytes by means of PIP2 depletion (6). Inhibition of M-current (KCNQ K+ channels) by muscarinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptor activation has recently been shown to be mediated by PIP2 depletion (7, 8).

One of the most important properties of signaling mechanisms is specificity. In respect to PIP2 as a second messenger, it is not yet clear whether GqPCR-induced changes in PIP2 can act as a specific signal. We have recently found that GIRK channels in atrial myocytes are inhibited by PIP2-dependent pathways in response to the activation of α1-adrenergic receptors (6), whereas M1/M3 muscarinic receptors have no effect on GIRK channels (9), suggesting that there is differential regulation of GIRK channels by different GqPCRs. However, evidence for coupling specificity between Gq-coupled receptors and GIRK channels is still lacking.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of various GqPCR agonists, including phenylephrine (PE), ACh, endothelin-1 (ET-1), prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α), bradykinin (BK), and angiotensin II (AngII), on GIRK currents in mouse atrial myocytes. It is well known that activations of these GqPCRs stimulate hydrolysis of PIP2 in cardiac myocytes (10–12). We confirmed that all of these agonists can inhibit GIRK currents by means of depletion of PIP2. However, the potencies and kinetics of inhibition differ widely among different agonists, suggesting that GqPCR-induced regulations of GIRK channels are receptor-specific.

Materials and Methods

Cell Isolation. Mouse atrial myocytes were isolated by perfusing a Ca2+-free normal Tyrode solution containing collagenase (0.14 mg/ml, Yakult Pharmaceutical, Tokyo) on a Langendorff column at 37°C as described (9). Isolated atrial myocytes were kept in high K+, low Cl– solution at 4°C until use.

Solutions and Chemicals. Normal Tyrode solution contained 140 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 5 mM Hepes, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The Ca2+-free solution contained 140 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 5 mM Hepes, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The high-K+ and low-Cl– solution contained 70 mM KOH, 40 mM KCl, 50 mM l-glutamic acid, 20 mM taurine, 20 mM KH2PO4, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM Hepes, and 0.5 mM EGTA. The pipette solution for perforated patches contained 140 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM EGTA, titrated to pH 7.2 with KOH.

ACh (Sigma) was dissolved in deionized water to make a stock solution (10 mM) and stored at –20°C. On the day of experiments, one aliquot was thawed and used. Calphostin C (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and wortmannin (WMN; Biomol) were first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO) as a stock solution and then used at the final concentration in the solution. PE, ET-1, AngII, BK, and PGF2α were from Sigma. All experiments were conducted at 35 ± 1°C. When required, 10 μM glibenclamide was applied in the presence of ACh to inhibit the ATP-sensitive K+ channel. To ensure a rapid solution turn-over, the rate of superfusion was kept >5ml/min, which corresponded to 50 times bath volume (100 μl/min).

Voltage-Clamp Recording and Analysis. Membrane currents were recorded from single isolated myocytes in a perforated patch configuration by using nystatin (200 μg/ml, ICN). Voltage-clamp was performed by using an Axopatch-1C amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). The patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate capillaries (Harvard Apparatus) by using a Narishige puller (PP-83, Narishige, Tokyo). The patch pipettes used had a resistance of 2–3 megaohms when filled with the above pipette solutions. Electrical signals were displayed during experiments by using an oscilloscope (TDS 210, Tektronix) and a chart recorder (Gould, Cleveland). Voltage-clamp and data acquisitions were performed by using a digital interface (Digi-data 1200, Axon Instruments) coupled to an IBM-compatible computer at a sampling rate of 1–2 kHz, filtered at 5 kHz.

Delivery of PIP2 to Cells. Bodipy-FL-PIP2 (Molecular Probes) was dissolved in deionized water to make a stock solution (1 μg/μl) and stored at –20°C. On the day of experiments one aliquot was thawed and used. Phosphoinositide–Shuttle PIP complex was prepared by mixing 2 μl of 1 μg/μl phosphoinositide stock solution with 2 μl of 0.5 mM Shuttle PIP stock solution. Cells were incubated with complex solution for 30–45 min and then superfused with standard bath solution.

Statistics and Presentation of Data. Results in the text and the figures are presented as mean ± SE. (n = number of cells tested). Statistical analyses were performed by using Student's t test. The difference between two groups was considered to be significant when P < 0.01 and not significant when P > 0.05.

Analysis of GqPCR-Induced Inhibition of GIRK Current (IGIRK). An explanation of the method used to compare the effect of GqPCR agonists on GIRK current between different cells can be found in Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Results

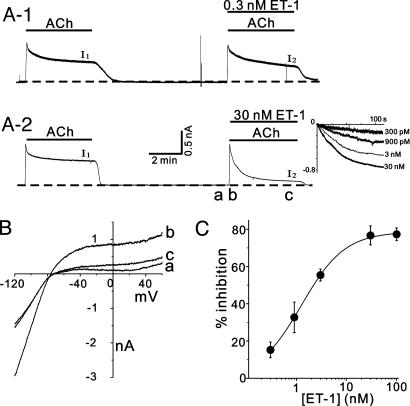

Effect of Various GqPCR Agonists on GIRK Currents. The protocol of the experiments for investigating the effect of GqPCR activation on IGIRK is shown in Fig. 1. In response to sustained stimulation by ACh (10 μM), atrial cells exhibited K+ current activation that reached a peak within several hundred milliseconds and gradually decreases to a quasi-steady-state level within 4 min (Fig. 1 A). This characteristic reduction in the K+ current in the continuous presence of ACh is referred to as short-term desensitization, in that several different mechanisms such as channel dephosphorylation, nucleotide exchange and hydrolysis cycle of the G protein, receptor phosphorylation by means of receptor kinase(s), and subsequent events (such as receptor internalization) are involved (13–16). We confirmed that the short-term desensitization recovered after washout of ACh, so that IGIRK during a second stimulation to ACh 6 min later (I2) was almost identical to that during the first stimulation (I1) (6). When various GqPCR agonists were applied together with ACh in the second stimulation, however, the decay phase of I2 was significantly accelerated compared with I1, without significant changes in peak currents. We regarded this difference as an indication of receptor-mediated inhibition of IGIRK. Fig. 1 A illustrates typical examples of these experiments showing the effects of ET-1 at low (0.3 nM) and high (30 nM) concentrations. Addition of ET-1 in the second stimulation accelerated the current decay in a dose-dependent manner, with the result that the amplitude of I2 measured at 4 min was reduced significantly compared with that of I1. Current-voltage (I–V) curves for IGIRK obtained at peak (Fig. 1B, trace b) and after 4 min (Fig. 1B, trace c) in the presence of ET-1 were illustrated with the control I–V curve (Fig. 1B, trace a). ET-1 did not affect the degree of inward rectification and the reversal potential, indicating that ET-1 modulates IGIRK itself, rather than modulating other current systems. ET-1-induced inhibition of IGIRK was calculated as (I1 – I2)/I1, where the current amplitude is measured at 4 min and the concentration-dependent relationship was plotted in Fig. 1C. At maximum concentration, the magnitude of inhibition was 82.4 ± 1.2% (n = 3). The concentration for half maximal inhibition (IC50) was 1.28 ± 0.05 nM, and the Hill coefficient was 1.00 ± 0.04. To analyze the time course of GqPCR-induced inhibition of IGIRK, the difference current (ΔIGIRK) was obtained by subtracting I2 from I1. ΔIGIRK was then normalized to the control IGIRK for the comparison between different cells (see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The normalized traces for ΔIGIRK at different concentrations are shown in Fig. 1 A Inset. The normalized traces of ΔIGIRK showed that the kinetics of inhibition by different concentrations of ET-1 were similar despite different degrees of inhibition.

Fig. 1.

ET-1 receptor-mediated inhibition of GIRK current. (A) Chart recordings of whole-cell current recorded at holding potential of –40 mV. The dotted line indicates zero current level. The applications of ACh and ET-1 are indicated by the horizontal lines above the trace. (Inset) Superimposed time course of ET-1-induced inhibition of IGIRK at various concentrations. (B) I–V relationships obtained at the times indicated by traces a–c in A. (C) Concentration-dependent relationship for ET-1. The magnitude of inhibition was plotted against ET-1 concentration (n = 3 ≈ 6 for each concentration).

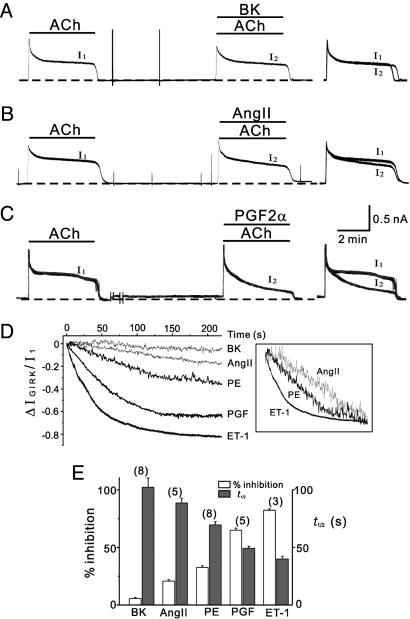

By using the same experimental protocol, the effects of PGF2α, AngII, and BK on IGIRK were investigated at the maximum concentration known for each agent. Representative current recordings demonstrating the effect of each agent are illustrated in Fig. 2 A–C, showing that each agonist affected IGIRK to a different extent. The magnitudes of inhibition over 4 min induced by PGF2α, AngII, and BK were 65.1 ± 1.9% (n = 5), 20.8 ± 1.1% (n = 5), and 5.3 ± 0.8% (n = 8), respectively (Fig. 2E). To compare the inhibitory effects of different GqPCRs on IGIRK in detail, the normalized traces for ΔIGIRK at supramaximal concentrations for each agent are obtained by the same method as used in Fig. 1 A Inset. Because normalized traces of ΔIGIRK for each agonist showed little variation among cells, we superimposed representative traces for each agonist in Fig. 2D. It is noted that different GqPCR agonists have distinctive inhibition profiles in terms of both potency and kinetics. We also confirmed that the profiles of GqPCR-induced inhibition are independent of the short-term desensitization of the control IGIRK (see Supporting Text). To compare the kinetics of current inhibition by different agonists more clearly, normalized traces for ΔIGIRK were scaled differently to adjust the values at 4 min to the same level (Fig. 2D Inset). These results show that, when the potency of inhibition is greater, inhibition develops more rapidly. In cases of agonists with lower potency, inhibition developed much more slowly after characteristic lag periods. Considering that ET-1-induced inhibition did not show such a slow kinetics even at low concentrations, it may be suggested that kinetics is not dependent on the magnitude of inhibition, but characteristic of each receptor. As a parameter representing the kinetics of inhibition, the time required for 50% of total inhibition, t1/2, was calculated. The mean values for ET-1, PGF2α, PE, and AngII were 40 ± 2.5 s (n = 3), 49.3 ± 1.7 s (n = 5), 69.6 ± 2.7 s (n = 8), and 88.7 ± 4.3 s (n = 5), respectively. Summarized data illustrated in Fig. 2E well demonstrate characteristic relationships between potency and kinetics of GIRK current inhibition by different agonists, in that the kinetics becomes faster as the potency increases.

Fig. 2.

Differential regulation of GIRK current by different GqPCRs. (A–C Left and Center) BK (10 μM), AngII (100 nM), and PGF2α (10 μM)) were applied together with second application of ACh (10 μM), repectively. (Right) Current traces in control (I1) and in the presence of each GqPCR agonist (I2) are superimposed to show the effect of the drugs on IGIRK. Note that each agonist inhibited IGIRK to a different extent. (D) Time course of IGIRK inhibition by BK, AngII, PE, PGF2α, and ET-1, from experiments as shown in A–C and in Fig. 1. ΔIGIRK was obtained by the method shown in Supporting Text and superimposed. (Inset) Scaled to match the same minimum value. (E) Summarized data of potency and t½of PIP2-dependent current inhibition. The numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of cells.

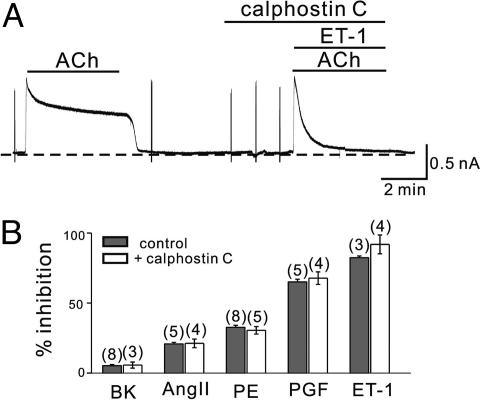

GqPCR-Induced Inhibition of GIRK Is Mediated by Means of the Depletion of PIP2. To elucidate the mechanisms for GqPCR-induced inhibition of IGIRK, we blocked each step of the signal transduction pathway related with GqPCRs. When a PKC inhibitor, calphostin C (2.5 μM), was pretreated before the application of ET-1 at the second exposure to ACh, inhibition of IGIRK by ET-1 was not affected (Fig. 3A). The magnitude of inhibition (%) during 4 min in the presence of ET-1 and calphostin C was 91.9 ± 6.7% (n = 4), indicating no significant difference from that in the presence of ET-1 alone (82.4 ± 1.2%, n = 3). The effect of calphostin C on PGF2α-, AngII-, and BK-induced inhibition of IGIRK was also tested. Summarized data are shown in Fig. 3B, indicating that activation of PKC is not involved in GqPCRs-mediated IGIRK inhibition. Furthermore, phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDB, 100 nM), a specific PKC activator, did not affect IGIRK. We applied PDB together with ACh in the second stimulation and compared the amplitude of the peak current and extent of short-term desensitization during 4 min between first and second IGRIK. Data comparing control condition vs. a treatment with PDB showed no significant difference (17), suggesting that GIRK channels in mouse atrial myocytes are not regulated by PKC.

Fig. 3.

Effect of calphostin C on GqPCR-induced GIRK inhibition. (A) Calphostin C (2.5 μM) was pretreated 3 min before the second application of ACh (10 μM) and ET-1 (30 nM). (B) By using the same experimental protocol, the effect of calphostin C on BK-, AngII-, PE-, and PGF2α-induced inhibition of IGIRK was tested and data were summarized. The magnitude of inhibition (%) during 4 min in the control group and the calphostin C-treated group was not significantly different. The numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of cells.

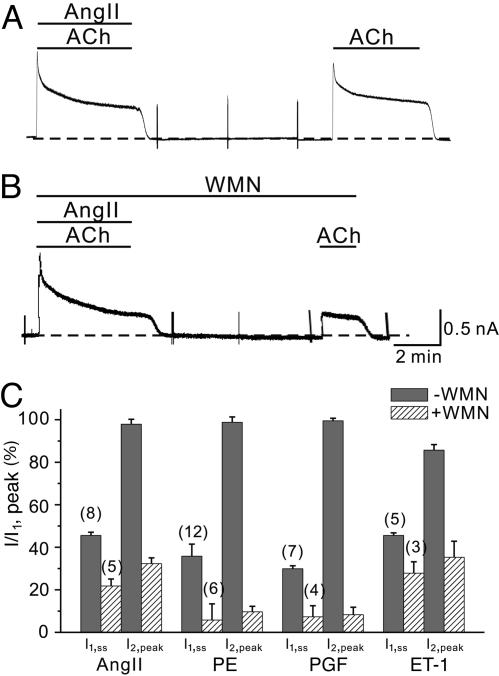

To test whether the GqPCR-induced inhibition of GIRK currents is mediated by PIP2 depletion, we used WMN, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI4-kinase), as was used in previous studies for the same purpose (6, 8, 18). Because the replenishment of PIP2 after depletion depends on PI4-kinase, WMN potentiates the depletion of PIP2 by PLC and blocks the recovery (19). A typical protocol of the experiment using AngII is shown in Fig. 4. We first confirmed the full recovery of IGIRK after a 6-min washout of AngII (Fig. 4A), and then repeated the same protocol in the presence of 100 μM WMN (Fig. 4B). In the presence of WMN, AngII-induced inhibition of IGIRK was potentiated, and IGIRK was no longer recovered after washout of AngII. The same series of experiments were performed using PE, PGF2α and ET-1. To observe the potentiation effect of WMN, ET-1 was used at low concentration (0.3 nM). To demonstrate the effect of WMN on the GqPCRs-mediated inhibition of IGIRK and the recovery from inhibition, the amplitude of I1 at steady state (I1,ss) and the peak amplitude of I2 (I2,peak) were normalized to the peak amplitude of I1 (I1,peak) and plotted in Fig. 4C. Potentiation of GqPCR-induced inhibition and abolishment of recovery after washout by WMN were observed in all agonists tested, suggesting that GqPCR-induced inhibition of GIRK current by these agonists is mediated by PIP2 depletion. However, the possibility of the involvement of unknown types of enzymes in the recovery from the receptor-mediated inhibition could not be entirely excluded, because WMN could have nonspecific effects on the enzymes other than PI kinases at this high concentration (20). However, specific blockers for PI4-kinase are not yet available. Therefore, for further confirmation, we tested whether loading atrial myocytes with PIP2 blocks GqPCR-induced inhibition of GIRK current.

Fig. 4.

WMN blocks the recovery from receptor-mediated IGIRK inhibition. (A) Recovery of the AngII effect on IGIRK. (B) In the presence of WMN (100 μM), inhibition of IGIRK was potentiated, and the recovery of current after washout of AngII was completely blocked. (C) Summary data of the relative amplitudes (percent) of I1,ss and I2,peak in respect to I1,peak. IGIRK was measured at –40 mV. The numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of cells.

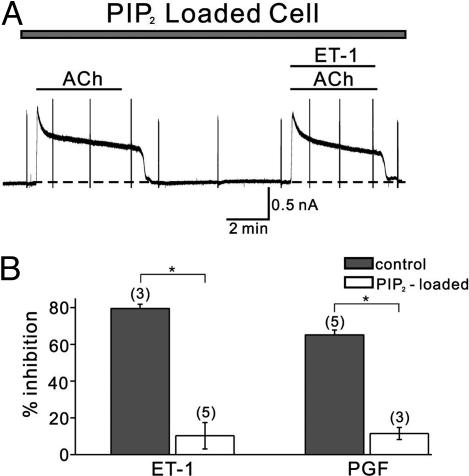

To apply the PIP2 into the cell, PIP2 (10 μM) was added in the pipette solution, and the conventional whole-cell mode was accomplished by rupturing membrane after giga-seal was made. When IGIRK in the absence and in the presence of ET-1 was recorded with the same protocol shown in Fig. 1, ET-1 showed only a small effect on IGIRK (13.5 ± 2.3%, n = 4). However, we could not compare this value with the control, because our control data were all obtained by the nystatin-perforated patch-clamp technique. Therefore, we tried to load cells with PIP2 by bath application using bodipy-labeled PIP2 together with shuttle PIP carrier, which is known to be easily inserted into membrane by application in the bath solutions (21). IGIRK was recorded by the nystatin-perforated patch-clamp technique in cells where successful loading was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5A). The amplitude of IGIRK and the extent of short-term desensitization during 4 min were 845.8 ± 125.3 pA and 43.5 ± 3.4% (n = 6), respectively. These values are not different from the control values, suggesting that, under normal conditions, the concentration of PIP2 in the membrane is not a limiting factor for activation of IGIRK. On the other hand, the ET-1-induced inhibition of IGIRK was significantly attenuated in cells loaded with PIP2 from 82.4% (Fig. 1) to 10.1 ± 7.2%. PGF2α-induced inhibition of IGIRK was similarly attenuated in cells loaded with PIP2. The data are summarized in Fig. 5B. These results further support that the inhibition of IGIRK by GqPCRs is caused by depletion of PIP2.

Fig. 5.

Loading of atrial myocytes with PIP2. (A) The same series of experiments from Fig. 1 were performed in myocytes loaded with PIP2. Note that ET-1-induced inhibition of IGIRK is attenuated (representative recording). (B) Summarized data of ET-1 and PGF2α. The numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of cells. *, P < 0.01.

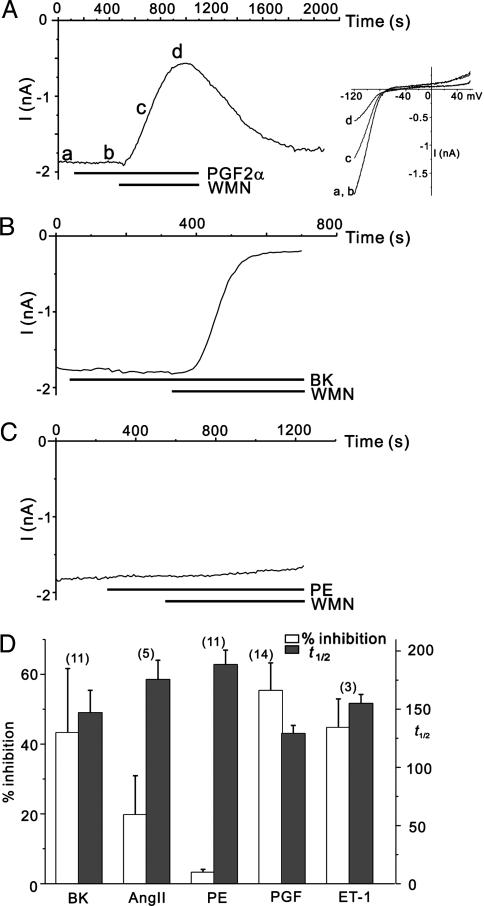

Regulation of IRK Channel by GqPCR. Characteristic features in the ΔIGIRK profile for each agonist may represent that the PIP2 depletion profile induced by each agonist is different. If GqPCR-induced PIP2 depletion occurs uniformly in the entire cell, and each GqPCR induces a distinct PIP2 depletion profile, PIP2-interacting other channels should be affected in the same characteristic manner. To test this idea, we investigated how other PIP2-dependent ion channels are affected by various GqPCR agonists. Because PIP2-channel interactions are known to be crucial for channel activity of inward rectifier K+ (IRK) channels encoded by Kir2.1 (4, 22, 23) and they are heavily expressed in cardiac myocytes, we tested the effect of agonists on IRK. Fig. 6A shows a representative result obtained for PGF2α. At a holding potential of –120 mV, IRK current was recorded as an inward current. Characteristic inward rectification for IRK was confirmed by plotting I–V relationships obtained from the current response to the voltage ramp from –120 mV to +60 mV (Fig. 6A Inset). IRK currents were not affected by PGF2α alone, but, when PIP2 depletion was further accelerated by WMN, the current began to decrease slowly. The kinetics of IRK inhibition was much slower, and the t1/2 was usually >100 s. To confirm whether the changes in holding current represent the changes in IRK, we obtained I–V curves. All curves show typical inward rectification known for IRK, indicating that the decrease in current amplitude at –120 mV represents the decrease in IRK (Fig. 6A Inset). The magnitude of inhibition of IRK by PGF2α in the presence of WMN varied in a wide range among cells (12.6–90.5%, n = 14). By using the same experimental protocol, the effects of PE, AngII, ET-1, and BK on IRK were investigated. None of these agonists affected IRK current, but they could inhibit IRK in the presence of WMN. Because the WMN alone or GqPCR agonist alone did not affect IRK, agonist-dependent IRK inhibition in the presence of WMN was regarded to be PIP2-dependent. BK, which showed a minimum inhibition on GIRK currents (Fig. 2) could induce an inhibition as large as PGF2α for IRK currents (Fig. 6B), but the effect showed a wide range of variation among cells (1.5–88.0%, n = 11). PE, which showed the medium potency in inhibiting GIRK currents, did hardly inhibit IRK currents (Fig. 6C). Characteristic relationships between the potency and t1/2 kinetics shown in GqPCR-induced GIRK inhibition by different agonists (Fig. 2E) were not observed in IRK inhibition (Fig. 6D). The difference between IRK and GIRK regulation is not consistent with the idea that each GqPCR induces a distinct profile of PIP2 depletion that is uniform throughout the cell. An alternative explanation is that GqPCR-induced PIP2 depletion is localized to the microdomain, and that each GqPCR has a specific spatial arrangement with PIP2-dependent target proteins. It can be thus suggested that the characteristic feature of GqPCR-induced GIRK inhibition for each GqPCR agonist represent the hierarchy in coupling proximity between each GqPCR and the GIRK channel proteins.

Fig. 6.

Regulation of IRK channel by GqPCRs. (A) Representative recordings of the whole-cell current at the holding potential of –120 mV. The application of PGF2α (10 μM) and WMN (100 μM) is indicated by the horizontal bar below the trace. (Inset) I–V relationships obtained at the points indicated by a–din A. (B and C) By using the same experimental protocol in A, the effects of BK (10 μM) and PE (100 μM) on IRK were tested, respectively. (D) Summarized data of potency and t½of PIP2-dependent IRK inhibition. The numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of cells.

Discussion

Evidence that the change of PIP2 level per se acts as a novel signal to regulate GIRK channels has been accumulating (6, 17, 24–27). However, most of such experiments were done in heterologous expression system. To understand the physiological significance of this regulation, it is particularly important to investigate how the regulation of PIP2 level by normal signaling pathways in native cells affects PIP2-dependent ion channels. Cardiac myocytes, like most cells, contain multiple Gq-coupled receptors. It was reported that, in rabbit and guinea-pig atrial myocytes, GIRK channels were inhibited by α1-adrenergic receptor (28) and ET receptor (29), respectively. They suggested that these current changes are mediated by means of a pertussis toxin-insensitive GTP-binding protein, and do not seem to involve the activation of PKC, but they could not identify what mediates their effects (28, 29). In this study, we showed that five agents (PE, ET-1, PGF2α, AngII, and BK receptors) that with good certainty activate Gq/PLC-coupled pathways cause an inhibition of GIRK channels, and provided the evidence that depletion of PIP2 is a key step in this pathway. First, PKC inhibitor did not block GqPCR-induced GIRK inhibition. Second, inhibition of PI4-kinase with WMN prevented the GIRK channel recovery after receptor-mediated inhibition. Third, supplementation or loading of PIP2 reduced GqPCR-induced GIRK inhibition. Thus, we concluded that Gq-coupled receptor stimulation causes depletion in membrane PIP2 levels, which leads to the observed changes in GIRK channel activity.

It is worth noting that the result obtained in atrial myocytes in this study is not consistent with the results of previous studies performed in other systems. Expressed GIRK channels (30–33) or neuronal GIRK channels (34, 35) are reported to be inhibited by GqPCRs in a PKC-dependent manner. This discrepancy implies that GqPCR coupling to target protein differs depending on cell type, and/or other experimental manipulation such as overexpression of channel and receptor protein (36, 37).

The potency of inhibition of GIRK current by GqPCR agonists over 4 min (ET-1 > PGF2α > PE > AngII > BK) did not match with their potency in terms of PIP2 hydrolysis measured in rat cardiomyocytes (ET-1 > BK ≈ PE; ref. 10). This discrepancy also supports that there is coupling specificity of GqPCR and GIRK channels. In addition, we showed in the present study that the profiles of GqPCR-induced inhibition of GIRK channels by various agonists are not similar with those of IRK channels, suggesting that GIRK and IRK channels have different coupling with GqPCRs. Evidence for coupling specificity between GqPCRs and effector proteins is accumulating. A typical example was found in rat sympathetic neurons, which express both M1 muscarinic receptors and BK receptors (38, 39). Although stimulation of either receptor can activate PLC sufficiently to increase the formation of IP3 (40, 41) and diacylglycerol, with consequent mobilization of PKC (42), only BK receptors produce a significant rise in intracellular Ca2+ (40, 43), suggesting that IP3-dependent Ca2+ release channels couple closely with BK receptors, but not with M1 receptors. The receptor-specific inhibition of GIRK currents by different GpPCRs demonstrated in the present study may also be explained by the difference in coupling proximity. Rapid and profound inhibition of GIRK currents by ET-1 and PGF2α receptor stimulations may represent close colocalization between GIRK channels and these receptors, whereas little effect of BK and M1/M3 receptors on GIRK currents (9) represents lack of close coupling between them.

Cholinergic activation of GIRK channels in the heart is considered to be a major mechanism for the negative chronotropic effect of vagal stimulation (44–48). It is also well known that the effect of vagal stimulation fades gradually (vagal escape; refs. 49 and 50). Although desensitization of atrial GIRK currents has been known to be responsible for vagal escape (51), it is possible that inhibition of GIRK currents by diverse GqPCRs may also contribute to an early cessation of parasympathetic effect. The clinical importance of this interaction needs to be investigated in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Korea Research Foundation Grant 2002-041-E00008. H.C. and D.L. were supported by the BK21 Program from the Korean Ministry of Education.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PLC, phospholipase C; GqPCR, Gq protein-coupled receptor; GIRK, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+; IGIRK, GIRK currents recorded in the present study; PE, phenylephrine; ET-1, endothelin-1; PGF2α, prostaglandin F2α; BK, bradykinin; AngII, angiotensin II; ACh, acetylcholine; WMN, wortmannin; IGIRK, GIRK current; IRK, inwardly rectifying background K+; t½, time required for 50% of total inhibition; IP3, inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate.

References

- 1.Hilgemann, D. W. & Ball, R. (1996) Science 273, 956–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lupu, V. D., Kaznacheyeva, E., Krishna, U. M., Falck, J. R. & Bezprozvanny, I. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14067–14070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Womack, K. B., Gordon, S. E., He, F., Wensel, T. G., Lu, C. C. & Hilgemann, D. W. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 2792–2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang, C. L., Feng, S. & Hilgemann, D. W. (1998) Nature 391, 803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sui, J. L., Petit Jacques, J. & Logothetis, D. E. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1307–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho, H., Nam, G. B., Lee, S. H., Earm, Y. E. & Ho, W. K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suh, B. C. & Hille, B. (2002) Neuron 35, 507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang, H., Craciun, L. C., Mirshahi, T., Rohacs, T., Lopes, C. M., Jin, T. & Logothetis, D. E. (2003) Neuron 37, 963–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho, H., Hwang, J. Y., Kim, D., Shin, H. S., Kim, Y., Earm, Y. E. & Ho, W. K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27742–27747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clerk, A. & Sugden, P. H. (1997). J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 29, 1593–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul, K., Ball, N. A., Dorn, G. W., 2nd, & Walsh, R. A. (1997) Circ. Res. 81, 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilal-Dandan, R., Kanter, J. R. & Brunton, L. L. (2000) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 32, 1211–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shui, Z., Boyett, M. R. & Zang, W. J. (1997) J. Physiol. (London) 505, 77–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuang, H., Yu, M., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11727–11732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bünemann, M. & Hosey, M. M. (1999) J. Physiol. (London) 517, 5–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Böhm, S. K., Grady, E. F. & Bunnett, N. W. (1997) Biochem. J. 322, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho, H., Youm, J. B., Earm, Y. E. & Ho, W. K. (2001) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 424, 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie, L. H., Horie, M. & Takano, M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 15292–15297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willars, G. B., Nahorski, S. R. & Challiss, R. A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5037–5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cross, M. J., Stewart, A., Hodgkin, M. N., Kerr, D. J. & Wakelam, M. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25352–25355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozaki, S., DeWald, D. B., Shope, J. C., Chen, J. & Prestwich, G. D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11286–11291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang, H., He, C., Yan, X., Mirshahi, T. & Logothetis, D. E. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes, C. M., Zhang, H., Rohacs, T., Jin, T., Yang, J. & Logothetis, D. E. (2002) Neuron 34, 933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobrinsky, E., Mirshahi, T., Zhang, H., Jin, T. & Logothetis, D. E. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lei, Q., Jones, M. B., Talley, E. M., Garrison, J. C. & Bayliss, D. A. (2003) Mol. Cell 15, 1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wellner-Kienitz, M. C., Bender, K., Meyer, T. & Pott, L. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1642, 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang, L., Lee, J. K., John, S. A., Uozumi, N. & Kodama, I. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7037–7047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun, A. P., Fedida, D. & Giles, W. R. (1992) Pflügers Arch. 421, 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaguchi, H., Sakamoto, N., Watanabe, Y., Saito, T., Masuda, Y. & Nakaya, H. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 273, H1745–H1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogalski, S. L., Appleyard, S. M., Pattillo, A., Terman, G. W. & Chavkin, C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25082–25088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leaney, J. L., Dekker, L. V. & Tinker, A. (2001) J. Physiol. (London) 534, 367–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao, J., Wang, X., Chen, F., Wang, R., Rojas, A., Shi, Y., Piao, H. & Jiang, C. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 1087–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharon, D., Vorobiov, D. & Dascal, N. (1997) J. Gen. Physiol. 109, 477–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takano, K., Stanfield, P. R., Nakajima, S. & Nakajima, Y. (1995) Neuron 14, 999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrade, R., Malenka, R. C. & Nicoll, R. A. (1986) Science 234, 1261–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wellner-Kienitz, M. C., Bender, K. & Pott, L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37347–32354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovoor, A. & Lester, H. A. (2002) Neuron 33, 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marrion, N. V., Smart, T. G., Marsh, S. J. & Brown, D. A. (1989) Br. J. Pharmacol. 98, 557–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamilton, S. E., Loose, M. D., Qi, M., Levey, A. I., Hille, B., McKnight, G. S., Idzerda, R. L. & Nathanson, N. M. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 13311–13316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.del Rio, E., Bevilacqua, J. A., Marsh, S. J., Halley, P. & Caulfield, M. P. (1999) J. Physiol. (London) 520, 101–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bofill-Cardona, E., Vartian, N., Nanoff, C., Freissmuth, M. & Boehm, S. (2000) Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 1165–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsh, S. J., Trouslard, J., Leaney, J. L. & Brown, D. A. (1995) Neuron 15, 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cruzblanca, H., Koh, D. S. & Hille, B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7151–7156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakmann, B., Noma, A. & Trautwein, W. (1983) Nature 303, 250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breitwieser, G. E. & Szabo, G. (1985) Nature 317, 538–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfaffinger, P. J., Martin, J. M., Hunter, D. D., Nathanson, N. M. & Hille, B. (1985) Nature 317, 536–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carmeliet, E. & Mubagwa, K. (1986) J. Physiol. (London) 371, 239–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurachi, Y., Nakajima, T. & Sugimoto, T. (1986) Am. J. Physiol. 251, H681–H684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin, P., Levy, M. N. & Matsuda, Y. (1982) J. Physiol. (London) 243, H219–H225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boyett, M. R. & Roberts, A. (1987) J. Physiol. (London) 393, 171–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zang, W. J., Yu, X. J., Honjo, H., Kirby, M. S. & Boyett, M. R. (1993) J. Physiol. (London) 464, 649–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.