Abstract

The lysogenic state of bacteriophage λ is exceptionally stable yet the prophage is readily induced in response to DNA damage. This delicate epigenetic switch is believed to be regulated by two proteins; the lysogenic maintenance promoting protein CI and the early lytic protein Cro. First, we confirm, in the native configuration, the previous observation that the DNA loop mediated by oligomerization of CI bound to two distinct operator regions (OL and OR), increases repression of the early lytic promoters and is important for stable maintenance of lysogeny. Second, we show that the presence of the cro gene might be unimportant for the lysogenic to lytic switch during induction of the λ prophage. We revisit the idea that Cro's primary role in induction is instead to mediate weak repression of the early lytic promoters.

Keywords: CI protein, genetic switch, transcription

The λ prophage of Escherichia coli can escape lysogeny and enter lytic development by prophage induction (1). Induction is triggered by the host SOS response, which in turn is activated by damage to the host cell DNA. Thus, induction provides a way for the prophage to escape from a challenged or dying host. During lysogeny, the λ lytic genes are repressed by a phage-encoded repressor, the product of the cI gene (2). The lytic genes of λ are arranged in a sequential and temporal manner where the expression of one group of genes is required for expression of the next and henceforth. The CI repressor silences all of the lytic genes by preventing transcription from the two earliest lytic promoters. The regulatory region of promoter right (PR) and promoter left (PL) each contain an operator, operator right (OR) and operator left (OL), respectively, each consisting of three binding sites for CI (reviewed in ref. 3; see also Fig. 1B). In the lysogen, two CI dimers are bound cooperatively to OR1/OR2 and OL1/OL2 to prevent transcription from PR and PL. The CI dimer bound to OR2 activates transcription from maintenance promoter (PRM) by a direct protein–protein interaction with RNA polymerase (4–7). CI has a lower binding affinity for OR3 relative to OL3 and the other operators. Recent studies have shown that OR3 and OL3 are simultaneously occupied by CI in lysogens ≈60% of the time (8). CI binding to OR3 excludes RNA polymerase from initiating transcription from PRM, thus cI transcription is both positively and negatively autoregulated.

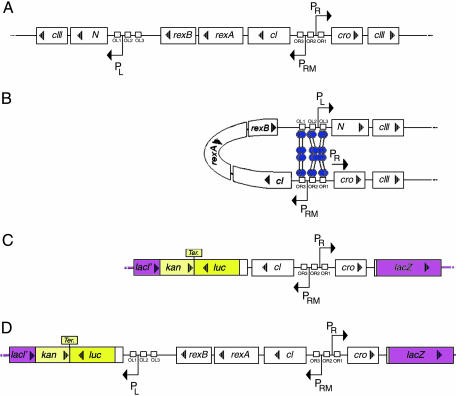

Fig. 1.

Genetic map of the immunity region of phage λ showing DNA looping and the various reporter gene fusions. (A) The λ immunity region. (B) The CI dimers bound to OL1/OL2 and OR1/OR2 can octamerize to create a DNA loop between the operators. (C) To create our reporter strains we placed part of the λ immunity region between the luc and lacZ reporter genes at the lac locus. NC414 and NC415 carry a rexA::luc and a cII::lacZ fusion. (D) NC416 and NC417 carry an N::luc and a cII::lacZ fusion.

The repression of PRM is enhanced by an OL–CI–OR complex, formed by octamerization of the CI dimers bound to OL1/OL2 and OR1/OR2 (refs. 9–11; see Fig. 1B); thus, the left operator region participates in the regulation of the right operator region and vice versa. The early lytic protein Cro, transcribed from PR, antagonizes CI after prophage induction (12, 13). Cro binds to the same three sites at OR and OL as CI binds, but does so with the opposite affinities of CI. When Cro binds to OR3, it prevents transcription of cI from PRM, and only at higher concentrations does Cro bind OR2/OR1 and repress transcription of PR. It has been proposed that Cro is also important for the regulation of the switch from lysogenic to lytic growth during λ prophage induction (12–14).

To induce the prophage, PR and PL must be derepressed to initiate transcription of the lytic genes. After initiation of the SOS response, this is accomplished through activation of the host RecA coprotease, which binds to CI and promotes autocleavage of CI (15). In a recA– host, SOS-mediated prophage induction is defective; the residual induction, caused by fluctuation of CI levels, occurs very rarely, less than once per million cells (16). This frequency is lower than that of mutational inactivation of the cI gene (17). Thus, the regulatory network maintaining lysogeny is extremely stable, more stable than the genes encoding it. The high stability is not obtained by precise control of the concentration of CI repressor because single-cell studies have shown that the concentration of repressor in stable lysogens vary greatly from cell to cell (11).

The switch between lysogenic and lytic growth of phage λ was the first genetic switch to be deciphered and the system has contributed immensely to our present understanding of developmental pathways (3). The recent observation that a DNA loop forms between OL and OR prompted us to investigate the role of the loop in the switching process of induction. We show here that the interaction between repressors bound at OL and OR increases the tolerance of the switch to fluctuations in CI concentration and argues against the role of Cro in the switch that leads to prophage induction.

Materials and Methods

Strains. All strains are derivatives of E. coli K12 and are listed in Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. The parent strain of all λ fusions, NC398, is a bidirectional reporter that carries the luciferase (luc) reporter gene on one direction and the β-galactosidase (lacZ) reporter gene on the other in the chromosome at the lac locus. Any promoter region of interest can be inserted into NC398. All constructs were made by using recombineering (18).

β-Galactosidase Assays. To determine the kinetics of PR activity upon temperature induction of cI857 lysogens, cultures were grown in LB (19) at 30°C overnight, diluted 1:200 the next morning, and induced by rapid transfer of the culture flasks to a 42°C water bath when OD600 reached 0.3–0.4. At each time point, 1 ml of culture was rapidly transferred to an Eppendorf tube on wet ice. After all time points had been collected and cooled, OD600 was recorded and a 0.5-ml sample was immediately mixed with 0.5 ml of Z-buffer (20) containing 25 μl of chloroform and 25 μl of 0.1% SDS. β-Galactosidase activity in the sample was then measured as described by Miller (20).

To determine the relationship between growth temperature and activity of PR in the cI857 lysogens, cultures were grown at 22°C overnight, diluted 1:200 the following morning, and incubated at the indicated temperatures to reach OD600 = 0.3–0.4. Samples were assayed for β-galactosidase activities.

Luciferase Assays. Luciferase activity was measured by using the reagents of the Promega Luciferase Assay System (catalog no. E1500) according to the company's directions (21). Cells were grown and treated as described for the β-galactosidase assays up to the point of addition of lysis buffer. Culture aliquots (0.1 ml) were centrifuged for 2 min at 21,000 × g, and pellets were resuspended in 0.4 ml of Cell Culture Lysis Reagent with 2.5 mg/ml BSA and 1.25 mg/ml lysozyme. Twenty microliters of cell lysate was mixed with 0.1 ml of luciferase substrate (Promega Luciferase Assay Reagent, catalog no. E151A), incubated for 120 s and read in EG&G Berthold Lumat LB 9507 single sample luminometer for 10 s. The relative light unit (RLU) was normalized to A600.

Results

The formation of an OL–CI–OR regulatory complex containing a DNA loop has been demonstrated to increase repression of PRM and PR (8, 10, 11). This additional level of regulation is required for the prophage's compensatory response to low doses of DNA damage, which sets the threshold level of DNA damage to which the prophage responds by induction (11). Repressor bound to OL can also increase repression of the PR promoter when artificially placed 3,600 bp downstream of the PR transcription start site, suggesting that the formation of an OL–CI–OR complex might also affect transcription from the early lytic promoters (9). To study the effects of the OL–CI–OR DNA loop on regulation of the early lytic promoters, we constructed PR::lacZ fusions by inserting part of the immunity region of λ between two reporter genes at the lac locus of E. coli as described in Supporting Text and Table 4, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, and shown in Fig. 1 C and D. The constructs fuse the cII gene with lacZ, rendering the expression of β-galactosidase under PR control. PR is one of the two early lytic promoters that are repressed in the lysogen but activated upon induction; thus, production of β-galactosidase in the fusion strains reflects induction of the lytic pathway.

Strains NC416 and NC417 contain the part of the λ immunity region ranging from the AUG initiation codon of gene N gene on the left to the 30th codon of cII on the right. These strains retain both the left and the right operator regions (Fig. 1D). In strains NC414 and NC415, only the right operator region is retained; the strains carry the λ immunity region from the AUG initiation codon of the rexA gene on the left to the 30th codon of cII on the right (Fig. 1C). The AUG codon of N or rexA is fused to the 2nd codon of the luc reporter gene, while the 30th codon of cII is fused to the 7th codon of lacZ. In strains NC414 and NC415, luciferase is expressed from PRM, whereas in NC416 and NC417, the reporter is under the control of the lytic PL promoter. The fusions also vary with respect to the cro gene. NC414 and NC416 carry the wild-type cro gene, whereas NC415 and NC417 carry a nonfunctional missense cro27 allele (12). Together, the four strains represent the four possible combinations of the  or ΔOL and cro+ or cro– genotypes.

or ΔOL and cro+ or cro– genotypes.

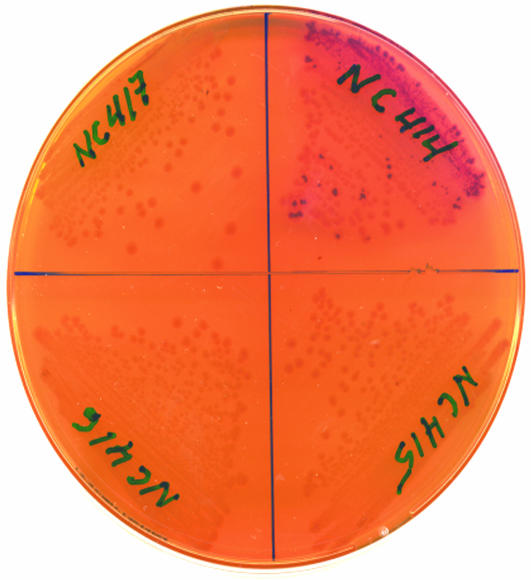

The OL–CI–OR Complex Increases Repression of PR in the Native Prophage Configuration. The expression of β-galactosidase in log phase NC414, NC415, NC416, and NC417 cultures growing at 30°C under repressed conditions is shown in Table 1. It is evident that the presence of the OL region increases repression of PR when the immunity region is located in the chromosome in its native configuration confirming the results obtained in multicopy systems (8–10). Note that our OL-deletion also removes the rex genes between OL and cI. We addressed the possibility that the decreased repression in the OL-deletion is not because of the absence of rex and demonstrated that the presence or absence of rex genes in the  background does not measurably affect repression of PR at temperatures ranging from 30°C to 37°C (data not shown). In the absence of functional Cro, the β-galactosidase activity is ≈4-fold higher in the absence of the left operator region than in its presence, reflecting that OL increases the repression of PR 4-fold. The 4-fold increase in PR activity with OL deleted is essentially the same as when CI is supplied at a constant level in trans (8–10), showing that OL is increasing the efficiency of PR repression at the normal lysogenic concentration of CI by >4-fold. We noted that in the absence of the left operator region, PR activity is decreased ≈30% in the cro– mutant (NC415) as compared to cro+ (NC414). This observation could either reflect a uniformly elevated expression from PR in the cro+ cells in comparison with the cro– cells, or it could reflect that a fraction of the cro+ population has switched to the “lytic” state where PR is not repressed by CI. The latter possibility is supported by the observation that, when the four strains are grown on MacConkey lactose agar plates, red colonies appear more frequently among NC414 (OL–cro+) cells than among NC415, NC416, and NC417 cells (Fig. 2). The red color indicates that these cells are producing higher levels of β-galactosidase, which metabolizes lactose. However, when both OL and OR regions are present, we were unable to detect any difference between cro+ and cro– in PR expression (Table 1, compare NC416 and NC417). This observation could indicate that the interaction between OL and OR prevents Cro from switching the prophage from the lysogenic to the lytic state. To examine this hypothesis further, we studied the activity of PR at low repressor concentrations. The cI allele present in our reporter strains is the cI857 allele, which encodes a temperature-sensitive repressor protein (22). The cI857 allele behaves as wild-type cI at 30°C, whereas there is essentially no repressor activity at temperatures above 40°C. Thus, a range of repressor activities can be obtained by growing the strains at a range of temperatures between the permissive and restrictive temperatures.

background does not measurably affect repression of PR at temperatures ranging from 30°C to 37°C (data not shown). In the absence of functional Cro, the β-galactosidase activity is ≈4-fold higher in the absence of the left operator region than in its presence, reflecting that OL increases the repression of PR 4-fold. The 4-fold increase in PR activity with OL deleted is essentially the same as when CI is supplied at a constant level in trans (8–10), showing that OL is increasing the efficiency of PR repression at the normal lysogenic concentration of CI by >4-fold. We noted that in the absence of the left operator region, PR activity is decreased ≈30% in the cro– mutant (NC415) as compared to cro+ (NC414). This observation could either reflect a uniformly elevated expression from PR in the cro+ cells in comparison with the cro– cells, or it could reflect that a fraction of the cro+ population has switched to the “lytic” state where PR is not repressed by CI. The latter possibility is supported by the observation that, when the four strains are grown on MacConkey lactose agar plates, red colonies appear more frequently among NC414 (OL–cro+) cells than among NC415, NC416, and NC417 cells (Fig. 2). The red color indicates that these cells are producing higher levels of β-galactosidase, which metabolizes lactose. However, when both OL and OR regions are present, we were unable to detect any difference between cro+ and cro– in PR expression (Table 1, compare NC416 and NC417). This observation could indicate that the interaction between OL and OR prevents Cro from switching the prophage from the lysogenic to the lytic state. To examine this hypothesis further, we studied the activity of PR at low repressor concentrations. The cI allele present in our reporter strains is the cI857 allele, which encodes a temperature-sensitive repressor protein (22). The cI857 allele behaves as wild-type cI at 30°C, whereas there is essentially no repressor activity at temperatures above 40°C. Thus, a range of repressor activities can be obtained by growing the strains at a range of temperatures between the permissive and restrictive temperatures.

Table 1. Activity of β-galactosidase in repressed lysogens.

| Strain (relevant genotype) | β-Galactosidase activity, Miller units |

|---|---|

| NC414 (ΔOL, cro+) | 21 (3.1) |

| NC415 (ΔOL, cro-) | 15 (1.1) |

NC416 ( , cro+) , cro+) |

4 (1.2) |

NC417 ( , cro-) , cro-) |

4 (1.3) |

The OL-CI-OR complex increases repression of PR 4-fold. Samples were grown at 30°C and assayed for β-galactosidase activity in early log phase as described in Materials and Methods. The averages of four independent experiments are shown. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Fig. 2.

Morphology of NC414–417 after growth at 30°C on MacConkey lactose agar (20). The colonies were grown for 42 h after restreaking from single colonies.

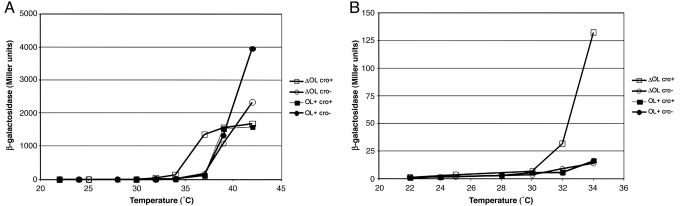

Role of Cro in the Switch Process? The expression of lacZ as a function of growth temperature for NC414, NC415, NC41,6 and NC417 is shown in Fig. 3. If cro is critical for the switch (14), we expect that derepression of PR will occur at lower temperatures in the cro+ than in the cro– cells, suggesting that Cro can sway the switch from lysogenic to lytic growth at intermediate concentrations of CI. We obtained that result for the strains that do not carr y the left operator region: NC414(cro+) and NC415(cro–) (Fig. 3). However, the expected pattern was not seen in the strains that carry both the left and the right operator regions. Although the role of rex genes, if any, in the switch process remains to be investigated in strains containing both operator regions, no difference in β-galactosidase levels were observed between NC416(cro+) and NC417(cro–) cells. In fact, the derepression of PR as a function of growth temperature appears identical for NC415, NC416, and NC417, suggesting that the DNA loop between the left and right operator region renders the switch insensitive to the presence of the cro+ gene.

Fig. 3.

β-Galactosidase activity as a function of growth temperature. (A) The activity of β-galactosidase at growth temperatures in the range between 22°C and 42°C. (B) A magnification of the left part of A, showing the activity of β-galactosidase at low temperatures. Open squares, NC414 (ΔOL cro+); open circles, NC415 (ΔOL cro–); filled squares, NC416 ( cro+); filled circles, NC417 (

cro+); filled circles, NC417 ( cro–). Assays were performed after 18 h of growth at the indicated temperatures. The absolute values reported here are different from those presented in Fig. 4 and Table 2, in which cases log phase cells were used. The average activity of two to four independent cultures are shown in Miller units.

cro–). Assays were performed after 18 h of growth at the indicated temperatures. The absolute values reported here are different from those presented in Fig. 4 and Table 2, in which cases log phase cells were used. The average activity of two to four independent cultures are shown in Miller units.

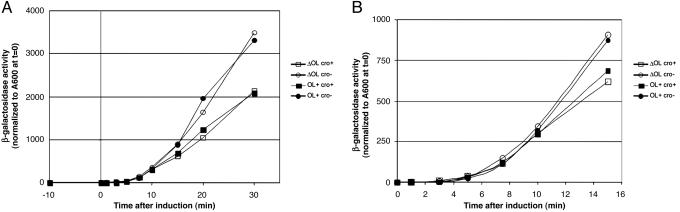

The Effect of Cro Mediated Repression of PR Transcription in the Presence and Absence of OL. We investigated whether the left operator region had any influence on the regulation of PR in the absence of functional CI. We inactivated CI by shifting growing cultures from 30°C to 42°C and followed the kinetics of PR derepression by monitoring β-galactosidase activity at various times after the temperature switch. The activities of β-galactosidase as a function of time after induction for NC414, NC415, NC416, and NC417 are shown in Fig. 4. For NC414 and NC416, which carry cro+, it can be seen that ≈10 min after induction, Cro presumably has accumulated to a level where it binds OR1 and/or OR2 and represses PR, causing the cro+ curves to diverge from the cro– curves (NC415 and NC417). It took equally long for Cro to accumulate to a concentration where it negatively autoregulates PR in NC414 (ΔOL) and NC416 ( ), and the degree of Cro-mediated repression of PR was similar in the two strains (Table 2). Therefore, we saw no indication that the left operator region participated in regulation of PR by Cro when CI was absent as expected (8), consistent with the hypothesis that OL participates in regulation at OR through the CI-mediated DNA loop (10).

), and the degree of Cro-mediated repression of PR was similar in the two strains (Table 2). Therefore, we saw no indication that the left operator region participated in regulation of PR by Cro when CI was absent as expected (8), consistent with the hypothesis that OL participates in regulation at OR through the CI-mediated DNA loop (10).

Fig. 4.

β-Galactosidase activity after thermal induction. (A) The β-galactosidase activities of NC414, NC415, NC416, and NC417 at various time points after shift of growth temperature from 30°C to 42°C normalized to A600 at the time of the temperature shift. Open squares, NC414 (ΔO–L cro+); open circles, NC415 (ΔOL cro–); filled squares, NC416 ( cro+); filled circles, NC417 (

cro+); filled circles, NC417 ( cro–). The β-galactosidase activities of cultures maintained at 30°C has been subtracted from all values. (B) A magnification of the left part A. The average activity of two to four independent cultures is shown.

cro–). The β-galactosidase activities of cultures maintained at 30°C has been subtracted from all values. (B) A magnification of the left part A. The average activity of two to four independent cultures is shown.

Table 2. Autorepression by Cro after prophage induction.

| Strain (relevant genotype) | Slope,* Miller units/min | cro-/cro+ |

|---|---|---|

| NC415 (ΔOLcro-) | 120 | 1.62 |

| NC414 (ΔOLcro+) | 74 | |

| NC417 (OL+cro- | 147 | 1.65 |

| NC416 (OL+cro+) | 89 |

β-Galactosidase activities were assayed as described in Materials and Methods.

Slope of the linear part of the induction curves shown are from Fig. 4.

Repression by Cro. It was suggested earlier on that the primary role of Cro in prophage induction is to repress the early lytic promoters, PR and PL, as well as the maintenance promoter PRM. The relationship between CI and Cro is that CI is a strong repressor specialized for complete turnoff of lytic functions, whereas Cro is a weak repressor functioning in a partial turn down of the early lytic promoters to allow progression into the late lytic phase (23, 24). Our unique divergent reporter constructs allowed us to measure the degree of repression of PR, PL, and PRM by CI and Cro in this study. To measure the degree of repression of PL by Cro, we compared the luciferase activity of NC416 (N::luc, cro+) and NC417 (N::luc, cro–) at 42°C, where CI857 is inactive (Table 3). Likewise, to measure the degree of repression of PRM by Cro, we compared luciferase in NC414 (rexA::luc, cro+) and NC415 (rexA::luc, cro–) at 42°C (Table 3). The degree of repression of PL and PR by CI in the presence of both the left and right operator regions was estimated by comparing the activity of the respective reporter genes in NC417(PR::lacZ, PL::luc, cro–) grown at 30°C, where CI857 is active, with NC417 grown at 42°C, where CI857 is inactive (Table 3). The luciferase protein is inherently heat sensitive and forms inactive aggregates after temperature shifts, but enzyme activity is restored with the aid of host chaperones after a few minutes at the high temperature (25). We observed full restoration of luciferase activity ≈15 min after shifting from 30°C to 42°C in a reporter containing wild-type CI (not heat-sensitive; strain WA5) (data not shown). Luciferase activities reported here were measured 60 min after the temperature shift. We observed that, in the absence of CI, Cro represses the PL promoter ≈1.7-fold (Table 3), although a stronger repression was reported when a fusion in which transcription terminators were present between PL and a reporter gene (galK) was used (26). In the current bidirectional reporter setup, Cro repressed PRM promoter ≈2.5-fold. (Table 3).

Table 3. Repression of PR, PL, and PRM by Cro and CI.

|

PR β-galactosidase, Miller units

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repression | OL+ | ΔOL | PL luciferase OL+, luc units | PRM luciferase ΔOL, luc units |

| Repression by Cro | ||||

| cro- | 1,516 | 1,555 | 5.9 × 106 | 6.7 × 105 |

| cro+ | 873 | 971 | 3.4 × 106 | 2.7 × 105 |

| Fold repression by Cro (cro-/cro+ in the absence of Cl at 42°C) | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| Repression by Cl | ||||

| 42°C | 1,516 | 5.9 × 106 | ||

| 30°C | 4 | 1.4 × 104 | ||

| Fold repression by Cl* (activity at 42°C/activity at 30°C) | 380 | 420 | ||

For repression by Cro in the absence of Cl, cultures of NC414, NC415, NC416, and NC417 were grown at 30°C overnight, then diluted and shifted to 42°C to reach OD600 = 0.3-0.4. β-galactosidase and luciferase activities were measured as described in Materials and Methods. For repression by Cl in the absence of Cro, cultures of NC417 were grown at 30°C overnight, then split, diluted 1:200, and incubated at 30°C and 42°C, respectively, to reach OD600 = 0.3-0.4. β-Galactosidase and luciferase activities were measured as described.

Repression of PL and PR by Cl varies from experiment to experiment because of variations of the repressed levels.

Discussion

Repression of PR by the OL–CI–OR Complex in its Native Configuration. Tight repression of PR is believed to be vital for the maintenance of lysogeny, because otherwise Cro would be produced, bind to OR3, and repress PRM, turning off cI transcription (27). Mathematical modeling studies of the lysis–lysogeny switch have concluded that CI bound at OR cannot repress Cro production sufficiently to stably maintain the lysogen unless there are additional levels of repression of PR (16, 28). We have confirmed that an interaction between the left and right operator region increases CI-mediated repression of PR 4-fold. Thus, our data are consistent with that of Revet et al. (9) and Dodd et al. (8) in suggesting that the DNA loop between OL and OR constitutes the missing level of regulation. Our data also support the model of Dodd et al. (8) to explain that the means by which the presence of OL allows tighter repression of PR at physiological CI concentrations. The extra level of cooperativity added by the formation of a CI octamer increases the binding affinity of CI to the involved operator sites, thus lowering the critical concentration of CI needed to maintain lysogeny.

OL Contributes to Repression of Cro Synthesis. According to the classic model, Cro's major role during induction is to bind OR3 and thereby inhibit cI expression from PRM (14, 27). If a Cro-mediated reduction in cI expression were important for effective induction of the early lytic promoters, we would expect a cI857 cro– prophage grown at intermediate temperatures to contain more repressor than the corresponding cro+ prophage, and thus require inactivation of a larger fraction of the repressor proteins to effectively derepress PR. Instead, we observe the same amount of derepression of PR at the same growth temperature in cro+ (NC416) and cro– (NC417), indicating that the same fraction of CI must be denatured to derepress PR in the two strains (Fig. 3). It is possible that differences in derepression temperature exist, which we cannot detect with our assay. The fraction of CI inactivated is not a linear function of the growth temperature, and it is likely that the concentration of active CI varies dramatically within a limited range of growth temperatures (22).

When OL–CI–OR complex formation is prevented by the absence of OL, PR is less repressed, more Cro is produced, PRM is more repressed, and less CI is made, so it is easier to switch to the lytic mode. In contrast, in the presence of OL, PR is tightly repressed, and so Cro production is blocked, thus maintaining the lysogenic mode. These results suggest that Cro may not play any role in the switch from lysogenic to lytic state of λ and are in agreement with the recent findings of Dodd and colleagues (8, 10), who showed that Cro may have a lesser role in prophage induction than previously perceived.

Cro as a Weak Repressor of Early Lytic Functions. The primary role of Cro in prophage induction may be to repress PR and PL after inactivation of CI (23, 24). In support of this hypothesis, a λcI857 cro– phage is capable of forming plaques when grown at 37°C, although no plaques are observed at 30°C or 42°C (24). Apparently, efficient plaque formation requires partial repression of the early lytic promoters and the repression can be exerted either by Cro or can, in the absence of Cro, be substituted by partially active CI. The Gibbs free energies of CI and Cro dimers binding to the operator regions (29, 30) support a stronger repression of PR and PL by CI than by Cro, and this has also been demonstrated for PR in vivo (31). Our double reporter constructs allowed us to measure the degree of repression of PR and PL by Cro and CI all in the same genetic background, allowing a direct comparison of the obtained values. As expected, we observe a much higher degree of repression of both lytic promoters by CI (≈400-fold) in the absence of Cro than by Cro (≈1.7-fold) in the absence of CI, consistent with the idea that CI acts as a strong repressor of lytic functions and Cro acts as a weak repressor of the early lytic promoters. Because Cro plays little, if any, role in effecting the lysogenic to lytic epigenetic switch, as discussed above, and because single-copy cro partly represses PRM and the lytic promoters, we conclude that this ability of Cro to partly repress PRM and/or the lytic promoters is not needed in inducing the “thermolabile lysogen.” Formally, it remains possible that Cro repression of one or more of these promoters is needed for induction of the complete prophage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stanley Brown, Kristoffer Bæk, and Amos Oppenheim for helpful discussions and Barry Egan and Ian Dodd for constructive criticisms of the manuscript and many helpful suggestions.

Author contributions: S.L.S., N.C., D.L.C., and S.A. designed research; S.L.S., N.C., and S.A. performed research; S.L.S., N.C., D.L.C., and S.A. analyzed data; and S.L.S., D.L.C., and S.A. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: OR, operator right; OL, operator left; PR, promoter right; PL, promoter left; PRM, maintenance promoter.

References

- 1.Weigle, J. J. & Delbruck, M. (1951) J. Bacteriol. 62, 301–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob, F. & Monod, J. (1961) J. Mol. Biol. 3, 318–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ptashne, M., Jeffrey, A., Johnson, A. D., Maurer, R., Meyer, B. J., Pabo, C. O., Roberts, T. M. & Sauer, R. T. (1980) Cell 19, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reichardt, L. & Kaiser, A. D. (1971) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 68, 2185–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, M., Moyle, H. & Susskind, M. M. (1994) Science 263, 75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuldell, N. & Hochschild, A. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 2991–2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bushman, F. D. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 230, 28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodd, I. B., Shearwin, K. E., Perkins, A. J., Burr, T., Hochschild, A. & Egan, J. B. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 344–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revet, B., von Wilcken-Bergmann, B., Bessert, H., Barker, A. & Muller-Hill, B. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodd, I. B., Perkins, A. J., Tsemitsidis, D. & Egan, J. B. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 3013–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baek, K., Svenningsen, S., Eisen, H., Sneppen, K. & Brown, S. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 334, 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisen, H., Brachet, P., Pereira da Silva, L. & Jacob, F. (1970) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 66, 855–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neubauer, Z. & Calef, E. (1970) J. Mol. Biol. 51, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson, A. D., Poteete, A. R., Lauer, G., Sauer, R. T., Ackers, G. K. & Ptashne, M. (1981) Nature 294, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little, J. W. & Mount, D. W. (1982) Cell 29, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aurell, E., Brown, S., Johanson, J. & Sneppen, K. (2002) Phys. Rev. E. Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 65, 051914-1–051914-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks, K. & Clark, A. J. (1967) J. Virol. 1, 283–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Court, D. L., Sawitzke, J. A. & Thomason, L. C. (2002) Annu. Rev. Genet. 36, 361–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertani, G. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186, 595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller, J. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 21.Promega (2000) Technical Bulletin (Promega, Madison, WI), no. 281.

- 22.Sussman, R. & Jacob, F. (1962) C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 254, 1517–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeda, Y., Folkmanis, A. & Echols, H. (1977) J. Biol. Chem. 252, 6177–6183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folkmanis, A., Maltzman, W., Mellon, P., Skalka, A. & Echols, H. (1977) Virology 81, 352–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroder, H., Langer, T., Hartl, F. U. & Bukau, B. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4137–4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adhya, S. & Gottesman, M. (1982) Cell 29, 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ptashne, M. (2004) A Genetic Switch: Phage λ Revisited (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 28.Reinitz, J. & Vaisnys, J. R. (1990) J. Theor. Biol. 145, 295–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darling, P. J., Holt, J. M. & Ackers, G. K. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 302, 625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda, Y., Ross, P. D. & Mudd, C. P. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 8180–8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer, B. J., Maurer, R. & Ptashne, M. (1980) J. Mol. Biol. 139, 163–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.