Abstract

Albumin is the most abundant plasma protein involved in the transport of many compounds, such as fatty acids, bilirubin, and heme. The endothelial cellular neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) has been suggested to play a central role in maintaining high albumin plasma levels through a cellular recycling pathway. However, direct mapping of this process is still lacking. This work presents the use of wild-type and engineered recombinant albumins with either decreased or increased FcRn affinity in combination with a low or high FcRn-expressing endothelium cell line to clearly define the FcRn involvement, intracellular pathway, and kinetics of albumin trafficking by flow cytometry, quantitative confocal microscopy, and an albumin-recycling assay. We found that cellular albumin internalization was proportional to FcRn expression and albumin-binding affinity. Albumin accumulation in early endosomes was independent of FcRn-binding affinity, but differences in FcRn-binding affinities significantly affected the albumin distribution between late endosomes and lysosomes. Unlike albumin with low FcRn-binding affinity, albumin with high FcRn-binding affinity was directed less to the lysosomes, suggestive of FcRn-directed albumin salvage from lysosomal degradation. Furthermore, the amount of recycled albumin in cell culture media corresponded to FcRn-binding affinity, with a ∼3.3-fold increase after 1 h for the high FcRn-binding albumin variant compared with wild-type albumin. Together, these findings uncover an FcRn-dependent endosomal cellular-sorting pathway that has great importance in describing fundamental mechanisms of intracellular albumin recycling and the possibility to tune albumin-based therapeutic effects by FcRn-binding affinity.

Keywords: albumin, endosome, Fc receptor, intracellular processing, intracellular trafficking, receptor recycling, cellular recycling

Introduction

Human serum albumin (HSA)3 is the most abundant plasma protein involved in transport of a wide range of compounds such as fatty acids, bilirubin, and heme, facilitated by multiple ligand-binding sites and an extended circulatory half-life (1). The binding and transport of endogenous ligands is vital to human health; however, a detailed understanding of the intracellular route taken by albumin is surprisingly still lacking.

Reports suggest engagement with the cellular recycling neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) diverts albumin from lysosomal degradation by an endosomal recycling pathway (2). FcRn comprises a type I transmembrane MHC class I-related heavy α chain that non-covalently associates with a β2-microglobulin light chain, responsible for Immunoglobulin G (IgG) diversion from lysosomal degradation by an endosomal cellular rerouting pathway after FcRn interaction (3). IgG is taken into the cell by pinocytosis and processed within endosomes at a low pH environment that triggers the binding to FcRn and consequent transport from the cell either by a transcytosis or recycling route dependent on the cell polarized state (4). Exposure to physiological extracellular pH triggers ligand release into the extracellular milieu (5). Although well described for IgG, only indirect evidence is available to apply this recycling pathway to albumin. The serum level of albumin in mice genetically modified to lack the FcRn expression has been found to be 2–3-fold lower than in a wild-type mice counterpart (2). Furthermore, Andersen et al. (6) found that recombinant human albumin variants engineered for enhanced FcRn-binding increases the blood circulatory half-life in mice and non-human primates (7).

This work presents the use of wild-type (WT) and engineered recombinant albumins with decreased and increased affinity to FcRn in combination with a low and high FcRn-expressing dermal human microvascular endothelium cell line (HMEC-1 and HMEC-1-FcRn, respectively) to define the role of FcRn in internalization, sorting, and rescuing of albumin from intracellular degradation. Intracellular trafficking of fluorescent-labeled albumins is investigated using a combination of confocal and flow cytometric techniques. Furthermore, a recycling assay is used for quantitative dynamic measurement of albumin recycling. The findings in this work provide the first direct evidence showing an FcRn-dependent endosomal recycling route that is vital to understand albumin's pivotal role in endogenous ligand transport and utilization to tune the pharmacokinetics of albumin-based therapeutics.

Results

Cellular uptake studies were performed in isogenic human endothelial cells derived from dermal microvasculature (HMEC-1) exhibiting a low (HMEC-1) or high expression (HMEC-1-FcRn) of human FcRn that was demonstrated by quantitative PCR (qPCR; 8–9-fold increase) and Western analysis (supplemental Fig. 1). Albumins with different FcRn affinity provided a tool to specifically investigate the role of FcRn in uptake and trafficking. FcRn affinity measured by Biolayer Interferometry showed a 15-fold decrease in affinity for the FcRn low-binding (LB) variant and a 24-fold increase for the FcRn high-binding (HB) variant compared with the WT variant at pH 5.5 (Table 1). Attachment of 5-carboxyfluorescein (5FAM) yielded a slight increase in binding affinity for WT and LB and a slight reduction for HB (+2.2-, −0.9-, +1.9-fold change for WT, HB, and LB compared with the unlabeled variant, respectively). A similar tendency was observed for Alexa594 (+3.9-, +0.1-, +4.2-fold change for WT, HB, and LB, compared with the unlabeled variant, respectively). Attachment of Alexa488, however, generally resulted in a decreased FcRn affinity (−0.6-, −0.6-, +0.7-fold change for WT, HB, and LB, compared with the unlabeled variant, respectively). However, with either of the fluorescent tags, the HB retained significantly higher FcRn-binding affinities than WT, and LB exhibits significantly lower affinities to FcRn than WT. The labeling efficiency, determined by the ratio of absorbance from the fluorophore and albumin for the 5FAM LB, WT, and HB was shown to be 1.6, 1.6, and 1.0, for the Alexa488 was 1.2, 1.3, and 1.0, and for the Alexa594 was 1.5, 1.0, and 1.0 (see supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Binding of conjugated and non-conjugated albumin variants against human FcRn at pH 5.5 and 7.0

Binding kinetics of recombinant albumin WT and FcRn low and high binder albumin (LB, HB) non-labeled or labeled with the different fluorophores 5FAM, AlexaFluor488, or AlexaFluor594 against the human FcRn measured at pH 5.5 or pH 7.0. The KD values are the average of three-six measurements, and each measurement consists of a seven-step dilution series for evaluation of kinetic parameters. NB denotes no detectable binding.

| Compound | pH 5.5 |

pH 7.0 KD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD average | S.D. | FcRn affinity (-fold change compared to the WT counterpart) | ||

| nm | nm | |||

| Unlabeled WT | 633.0 | 97.0 | NB | |

| 5FAM-WT | 293.2 | 20.9 | ||

| ALEXA488-WT | 1157.8 | 188.9 | ||

| ALEXA594-WT | 161.6 | 25.3 | ||

| Unlabeled HB | 26.3 | 3.7 | + 24.1 | NB |

| 5FAM-HB | 30.1 | 0.6 | + 9.7 | |

| ALEXA488-HB | 42.6 | 2.3 | + 27.2 | |

| ALEXA594-HB | 24.1 | 1.3 | + 6.7 | |

| Unlabeled LB | 9633.3 | 1439.9 | −15.2 | NB |

| 5FAM-LB | 4978.0 | 289.5 | −17.0 | |

| ALEXA488-LB | 13126.0 | 3875.9 | −11.3 | |

| ALEXA594-LB | 2276.7 | 515.8 | −14.1 | |

Flow cytometric analysis was used to measure the amount of retained fluorescence in HMEC-1 and HMEC-1-FcRn cells after 2 h of exposure to 8 μm Alexa488-labeled albumin (Fig. 1). A greater percentage of albumin was retained within the cells for the LB than the WT and HB after 1 h (78%, 46%, and 42%, respectively), and 2 h (53%, 21%, and 21%) in the HMEC-1 cells (Fig. 1, a–c). A similar amount of albumin was retained within the HMEC-1-FcRn cells for the LB; however, less WT and HB was retained within these cells at 1 h (80% LB, 23% WT, and 23% HB) and 2 h (55% LB, 15% WT, and 19% HB). Overall, similar levels for LB were observed between the two cell types, whereas the WT and HB were seemingly ejected from the cells more rapidly from the HMEC-1-FcRn cells (Fig. 1, a–c), suggestive of FcRn-mediated recycling.

Figure 1.

Albumin variants cellular uptake. a–c, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) detected by flow cytometry of low (HMEC-1) and high (HMEC-1-FcRn) FcRn-expressing cells after exposure to Alexa488-labeled recombinant albumin variants. Shown are FcRn low binder (LB) (a), WT (b), and FcRn high binder (HB) (c), at pH 6.0 for 2 h followed by incubation in HBSS (pH 7.4) for 0, 1, or 2 h. MFI was normalized to cells at t = 0 h for each albumin variant. Albumin uptake in HMEC-1 (d) and HMEC-1-FcRn (e) cells after exposure to 8 μm Alexa488-labeled LB, WT, and HB recombinant albumin variants at pH 6.0 or pH 7.4 for 2 h. Cellular MFI was determined by flow cytometry and normalized to non-treated cells.

To further confirm FcRn-driven uptake and trafficking of albumin, flow cytometric uptake studies were performed at a lower pH (pH 6.0), known to facilitate increased FcRn engagement (2) and demonstrated at pH 5.5 in Table 1. For the HMEC-1 cells, no significant differences in albumin uptake were observed between the three variants at both pH 6.0 and 7.4 (Fig. 1d). Albumin uptake in the HMEC-1-FcRn cells, however, showed an FcRn affinity-dependent uptake that was potentiated at pH 6.0 for WT and HB (Fig. 1e). Possible surface binding of albumin to FcRn in combination with retained albumin-FcRn-binding after recycling could explain the higher level of uptake for the WT and HB. At pH 7.4, only slight differences between the cellular fluorescence were observed between the variants in the HMEC-1-FcRn cells, although slightly higher values for the HB and WT compared with LB (14.2, 7.9, and 5.9, respectively). Much greater differences, however, were observed at pH 6.0 in the HMEC-1-FcRn cells, with the LB remaining constant at 4.9, whereas the HB and WT increased 3-fold (43.7 and 23.7, respectively). A trypan blue quenching assay at 4 °C and 37 °C was used to show the absence of surface-bound fluorescence and that cellular fluorescence was most probably due to internalized albumin (supplemental Fig. 2, b and c).

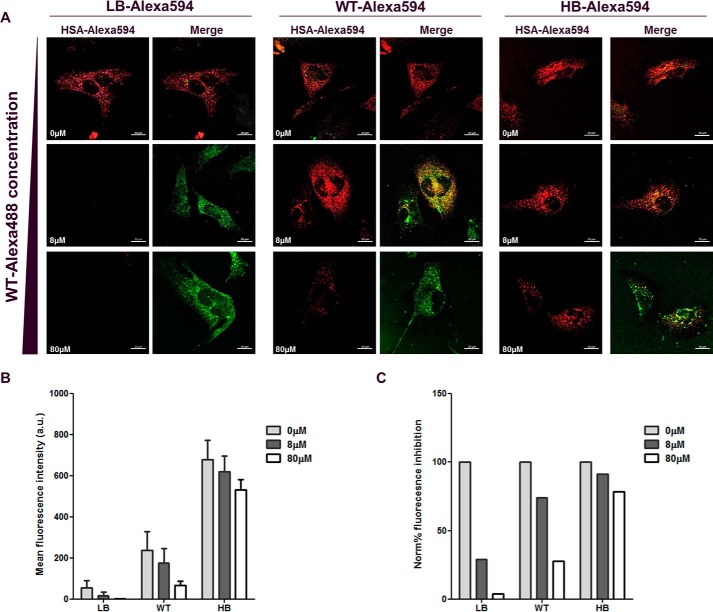

Confocal microscopy was used to further explore the FcRn–albumin affinity-dependent uptake in HMEC-1-FcRn cells. Cells were exposed to Alexa594-labeled LB, WT, and HB albumins at a concentration of 8 μm in the presence of equimolar or 10-fold excess of Alexa488-labeled WT albumin for 1 h followed by fixation. Fixed cells were imaged, and the fluorescence of Alexa594-labeled material was quantified. Again, the intracellular fluorescence increased proportionally to FcRn-binding affinity (Fig. 2, A and B). The relative drop in intracellular concentration was lower with increased FcRn-binding affinity (Fig. 2C). The HB variant resisted the challenge with only an ∼20% drop in the presence of 10-fold excess of competing WT albumin, whereas the LB was nearly 100% blocked. Higher affinity albumins likely occupy the receptors excluding variants with reduced affinity.

Figure 2.

Albumin variants cellular uptake in the presence of excess albumin competition. HMEC-1-FcRn cells were incubated with Alexa-594 labeled albumins WT, FcRn low binder (LB), and FcRn high binder (HB) at 8 μm in the presence of 0, 8, or 80 μm WT albumin labeled with Alexa488 at pH 6.0 for 1 h. A, representative confocal sections showing the intracellular accumulation of Alexa-594-labeled albumin with the distinct FcRn-binding affinities versus the intracellular accumulation of Alexa-488 WT albumin. B, plot of mean fluorescence intensity of Alexa-594-labeled albumin. The bars represent the mean ± S.D. of at least 10 cells. C, normalized % fluorescent inhibition whereby the Alexa594-labeled fluorescence in the absence of inhibitor is set to 100. Data are representative of at least 10 cells. Scale bar = 20 μm.

To investigate the involvement of endosomes in the albumin intracellular trafficking process as a consequence of FcRn-binding, fluorescent albumins labeled with the 5FAM were used. The assay is based on the spectral shift and consequent decrease in 5FAM intensity in the endosomal pH range (supplemental Fig. 2a), which is restored by cellular addition of the ionophore monensin that equilibrates the pH gradient between the cytoplasm and acidic compartments by triggering the exchange of protons for potassium ions (8). HMEC-1 and HMEC-1-FcRn cells were exposed to 8 μm 5FAM-labeled LB, WT, and HB for 2 h followed by assessment of the fluorescence uptake by flow cytometric analysis before and after incubation with monensin (20 μm) for 10 min at room temperature. In HMEC-1 cells, the addition of monensin resulted in an increase in cellular fluorescence of 24.4%, 44.8%, and 41.8% for LB, WT, and HB, respectively, whereas in HMEC-1-FcRn cells the increase was 4.2%, 44.0%, and 38.2% (Fig. 3). No significant differences were observed after the addition of monensin using the non-pH-sensitive Alexa488-labeled variants (supplemental Fig. 2, a, d, and e). The greater fluorescence increase for the WT and HB compared with LB in HMEC-1-FcRn cells after monensin addition suggests higher endosomal localization facilitated by the higher FcRn affinity.

Figure 3.

Albumin variants cellular uptake and endosomal involvement. a and b, albumin cellular uptake in HMEC-1 (a) and HMEC-1-FcRn (b) cells after exposure to 8 μm 5FAM-labeled WT, FcRn low binder (LB), and FcRn high binder (HB) recombinant albumin at pH 6. 0 for 2 h. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cells was measured by flow cytometry before and after incubation with monensin (20 μm) for 10 min.

Confocal microscopy was used to directly detect endosomal FcRn-driven compartmentalization sorting of Alexa594-labeled albumin variants after 1 h of incubation in HMEC-1-FcRn cells (Fig. 4). The spatial location of trafficking was determined by colocalization of the labeled albumins with each of the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-fused markers, Rab5 for early endosomes, Rab7 for late endosomes, and lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) for lysosomes. Punctuate fluorescence indicative of localization within vesicular compartments was observed for the LB, WT, and HB (Fig. 4A). Relative quantification of co-localization with the endosomal/lysosomal markers shows that all three albumins share an equal prevalence in early endosomes (Fig. 4B). For the HB albumin, increased co-localization with late endosomal marker RAB7 was observed with minimal presence in the lysosomes, which suggests cellular sorting and salvage from lysosomal degradation. In contrast, the LB was highly co-localized with LAMP1 lysosomal marker, which suggests subsequent trafficking to a lysosomal degradation environment. WT showed a somewhat intermediate trafficking with its presence in late endosomes comparable with HB but increased accumulation in lysosomes. To further confirm that the distinct compartmentalization was FcRn-binding–dependent, dextran co-localization with late endosomes and lysosomes was studied 30–60 min after removal of dextran. Dextran, as expected, was found almost exclusively within the lysosome compartment (supplemental Fig. 3). Together, this supports endosomal trafficking of albumin with subsequent FcRn-mediated diversion from lysosomal degradation. In parallel to the GFP-marker transfected cell method, endosomal localization in HMEC-1-FcRn cells was also observed by immunofluorescence staining in permeabilized cells, where almost no albumin was found to localize within the lysosomes for the WT and HB (supplemental Fig. 4). Both methods indicate the same overall trafficking of the albumin, and the slight deviations may be a product of cellular compartment labeling methods. Having demonstrated the predominant role of FcRn in albumin recycling and the underlying intracellular transport route, we aimed at establishing an in vitro assay to quantitate the albumin recycling dynamics.

Figure 4.

Albumin intracellular sorting. A, HMEC-1-FcRn cells expressing GFP early or late endosome markers (Rab5 and Rab7) or lysosome marker (Lamp1) were incubated with incubated with 8 μm Alexa-594-labeled WT, FcRn low, and FcRn high binder (LB, HB) albumins for 1 h at pH 6.0 before fixation. Projections were made of 3D image volumes for each fluorophore and were merged as single images (green, GFP markers; red, albumins; yellow, co-localization of albumin with markers). B, pixel co-localization was quantified as a percentage of albumin co-localized with the respective marker in the 3D structure. Co-localization with endosome markers Rab5 and Rab7 is associated with uptake and sorting, whereas co-localization with lysosome marker Lamp1 is associated with degradation. The bars represent the mean ± S.D. of at least 10 cells.

FcRn overexpressing HMEC-1-FcRn cells were seeded in culture plates and allowed to reach confluency before the assay. The cells were exposed to either LB, WT, or HB albumin at acidic pH (pH 6.0) during uptake followed by removal of extracellular albumin by thorough washing at physiological pH. Recycling was completed in neutral pH medium in which the quantification of released albumin was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Fig. 5A). The amount of recycled albumin was in the low ng/ml range, with ∼0 ng/ml, 4 ng/ml, and 10 ng/ml detected for LB, WT, and HB albumin, respectively. However, the significant differences between the variants demonstrate an FcRn-binding dependence. We observed a clear ∼3.3-fold improvement in recycling efficiency of the HB compared with WT based on 15 independent recycling experiments (Fig. 5B). Overexpression of FcRn and acidic pH during albumin uptake allowed the use of low albumin concentrations (0.15 μm) to avoid saturation of the system and to keep background levels low. To verify the correlation of FcRn engagement with recycling with different FcRn-binding molecules, immunoglobulin IgG but not IgY (chicken immunoglobulin which does not bind FcRn; Ref. 9) showed high recycling (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Endothelial cellular recycling of albumin. A, WT, FcRn high binder (HB), and FcRn low binder (LB) albumin variants were recycled in HMEC-1-FcRn cells. HMEC-1-FcRn cells were exposed to 0.15 μm albumin at pH 6.0 for 1 h to allow cellular uptake. After thorough washing of the cells, fresh pH 7.4 medium was added in which recycled albumin was quantified by ELISA after 1 h incubation. One representative of three experiments is shown. Student's t test was used for comparison of LB and HB albumin variants to WT. ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.D. B, 15 independent recycling experiments with WT and HB albumin were performed as in A, and data are presented as recycling efficiency relative to WT. Error bar, S.E. C, IgG and IgY were recycled as in A and measured by respective immunoglobulin specific ELISA. One representative of two experiments is shown. BD, Below detection. Error bars, S.D.

Interestingly, exposure to high albumin concentrations (8 μm) resulted in detectable recycling in untransduced HMEC-1 cells in addition to HMEC-1-FcRn cells (Fig. 6), with the previously observed recycling efficiency ranking (LB < WT < HB) maintained. In HMEC-1-FcRn cells, exposure to high albumin concentrations dramatically increased the levels of recycled WT and HB albumin, and even under physiological pH conditions during uptake, FcRn-dependent recycling was apparent. This supports that recycling in HMEC-1-FcRn cells is not a capacity gained by FcRn overexpression and that it is mechanistically similar to that in HMEC-1 cells. Moreover, the validity of the assay was further supported by the observation that albumin recycling required cell activity (supplemental Fig. 5). After albumin uptake and washing, moving the cells to cold temperatures (4 °C) efficiently inhibited its recycling and release, which was “turned on” again by increasing the temperature (37 °C). In contrast to release of cell surface-bound albumin, intracellular endosome-mediated albumin transport is seemingly temperature-sensitive.

Figure 6.

The effect of FcRn expression, pH, and albumin concentration on albumin recycling. WT, low (LB), and high FcRn binder (HB) albumin variants were recycled in HMEC-1-FcRn (A) and HMEC-1 (B) cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” All exposure cells received either 0.15 μm or 8 μm albumin where the pH was either 6.0 or 7.4. During recycling and release of albumin pH was 7.4 in all cases. The figures show concentrations of albumin measured in supernatants, and one representative of two experiments performed is shown. Student's t test was used to compare LB and HB albumin variants to WT. ***, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05. BD, below detection. NS, non-significant. Error bars, S.D.

The ability of measuring FcRn-dependent albumin recycling in vitro not only allows mechanistic studies of albumin recycling but also provides a valuable tool for assessing recycling efficiencies of albumin variants with improved FcRn-binding affinities. This is particularly relevant in the development of albumin-based half-life extension drug conjugates. This was validated with similar recycling observed for non-conjugated albumin and albumin conjugates (Alexa Fluor® 488 and a peptide (the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide) at molar equivalent concentrations (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

FcRn-dependent recycling of albumin variants conjugated to a small chemical molecule or peptide. WT, low (LB), and high FcRn binder (HB) albumin variants conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (A), exenatide (B), or non-conjugated were recycled in HMEC-1-FcRn cells and detected by ELISA as described in Fig. 5. Results are presented as relative recycling with WT albumin set as 100%. Error bars, S.D.

Discussion

HSA is the most abundant plasma protein that plays a vital role in the transport of molecules to maintain a physiological homeostasis. Despite this importance, its precise route of intracellular trafficking remains unclear, although mounting evidence suggests a prominent involvement of FcRn.

Early work focused on engagement with the megalin/cubilin receptor for avoidance of renal clearance. Maunsbach et al. (10, 11) demonstrated by electron microscopic autoradiography endocytotic uptake of I125-labeled albumin after micropuncture in rat proximal tubules. Subsequent studies on albumin intracellular trafficking has primarily been carried out in kidney cells predominantly the proximal tubule, with a focus on megalin/cubilin-mediated transcytosis (12–15) as a mechanism of salvage from renal clearance (16, 17). Predescu et al. (18) demonstrated, using transmission electron, microscopy transcytosis through the microvascular endothelium using gold-labeled albumin, whereas Carson et al. (19) identify lysosomal degradation of albumin within podocytes (19). Recent experimental data implicates a role for FcRn in the intracellular trafficking of albumin (14, 20). The intracellular FcRn-mediated albumin recycling pathway has not been studied in cells, but due to non-competitive shared FcRn-binding (21, 22) was thought to follow the well described route of IgG (4, 23–26). The recycling and salvage from lysosomal degradation of albumin by a singular receptor was originally proposed by Schultze and Heremans (27) as it was for IgG by Brambell (28). More recently, engineered recombinant variants of human albumin with enhanced FcRn-binding (6) were found to increase the blood circulatory half-life in mice and non-human primates thought as a consequence of FcRn recycling (7).

Although FcRn expression has been demonstrated in various tissues, the microvascular endothelium is believed to be the main site of FcRn-mediated IgG recycling (29, 30). In this study we, therefore, used isogenic human dermal microvascular endothelial (HMEC-1) cells with a low (HMEC-1) or high (HMEC-1-FcRn) FcRn-expression. Furthermore, we used a panel of recombinant human serum albumin variants (non-fluorescent or fluorescent-labeled) with different FcRn-binding affinities, engineered by single-point mutations in the C-terminal domain III, which is known to represent the major FcRn-binding site within albumin (7). An in vitro cell-based albumin recycling assay combined with flow cytometric and confocal microscopic techniques allows precise investigations into the role of FcRn-binding in albumin uptake and intracellular trafficking. The application of the HMEC-1-FcRn line with the isogenic parental cell line HMEC-1 should allow any differences in albumin trafficking to be attributed to FcRn expression rather than intercellular differences. The HMEC-1-FcRn line, but not the HMEC-1 cell line, however, was maintained under puromycin and G418 antibiotic selection conditions to maintain stable expression of FcRn in the former.

LB albumin was shown by flow cytometric analysis to be more retained in HMEC-1 cells than both WT and HB variants, an effect that was potentiated in HMEC-1-FcRn cells exhibiting overexpression of the FcRn (Fig. 1, a–c). This suggests FcRn-mediated recycling similar to IgG (4, 24). Brülisauer et al. (20), however, observed none or only a slight decrease in the total cell-associated fluorescence in HUVEC and Caco-2, respectively, up to 3 h after pulse-wash of fluorescent wild-type albumin using a flow cytometric analysis. The authors suggested cellular retention may be due to lower expression of FcRn in HUVEC than Caco2 cells.

Furthermore, we show an albumin-FcRn affinity-dependent uptake in HMEC-1-FcRn cells at both physiological pH and pH 6.0 with increased uptake for HB and reduced uptake for LB compared with the WT. Greater uptake observed at pH 6.0 seemingly reflects the higher FcRn engagement shown previously at low pH by surface plasmon resonance (5). In contrast to what we observed in HMEC-1-FcRn, we observed minimal differences between the three albumin variants in the low FcRn-expressing HMEC-1 cells. Together these findings indirectly demonstrate an FcRn-dependent uptake and clearance of albumin from the cells.

Flow cytometric uptake studies using the pH-sensitive 5FAM in combination with monensin revealed a greater fluorescence increase for the WT and HB after monensin addition in the HMEC-1-FcRn cells, which supports localization in a low pH environment suggestive of endosomal compartmentalization, ∼6.0–6.8 (31), facilitated by the higher FcRn affinity.

Confocal analysis using fluorescently labeled albumin and cellular markers allowed direct detection of the cellular location site of albumin. Determination of co-localization with cellular compartments was investigated by both endogenous expressing fluorescent cellular compartment markers and immunofluorescence staining. No significant differences in the trafficking pathway were found in both non-permeabilized cells or permeabilized cells. Punctuated fluorescence within the cells indicated cellular vesicular compartmentalization. The LB, WT, and HB were shown to co-localize within early endosomes, in agreement with the previous reports suggesting cellular uptake by endocytosis (10, 18, 20). All three variants were shown to localize with late endosomes that supports an endocytotic pathway; however, only the LB exhibited significant lysosome co-localization. This gives direct support for the necessity for FcRn-mediated salvage from lysosomal degradation. This is in contrast to the findings by Carson et al. (19) that FITC-labeled albumin is degraded within lysosomes in podocytes. This discrepancy may be due to labeling used and differences between cell types and different FcRn expression levels. Previously, Brülisauer et al. (20) demonstrated that modified WT albumin is found in RAB7-positive vesicles and exposed to a non- or only poorly bio-reducing environment in epithelial (Caco-2) and endothelial cells (HUVEC); however, the FcRn dependence was not addressed. We show albumin located in late endosomes; however, using the albumin variants, we show that reducing the FcRn affinity results in lysosomal accumulation. Albumin cellular trafficking would also be expected to be influenced by alternative albumin receptors reported in the literature such as the gp18, gp30 (32, 33), gp60 (34), and megalin/cubilin; however, the focus of this work was to investigate the role of FcRn in endosomal recycling.

By the use of the HMEC-1-FcRn cells we have developed a novel assay to quantitatively measure the cellular recycling of albumin. Similar assays have been demonstrated for IgG but were primarily based on epithelium and focusing on transcytosis (9, 35–39). We show the crucial role of FcRn during albumin recycling in vitro by the increased levels of albumin recycled by HMEC-1-FcRn cells compared with non-transduced HMEC-1 cells. Moreover, we demonstrate a significant increase in recycling efficiency of an albumin variant with improved FcRn-binding. These findings are in contrast to a previous report showing no effect of increased rat FcRn expression in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells on rat albumin transcytosis and recycling (40).

The application of albumin as a drug carrier represents an attractive approach for drug circulatory half-life extension and efficacy improvement (41–43). Hence, the in vitro quantification of albumin recycling provides a useful tool for predicting in vivo half-life of albumin variants and their drug conjugated counterparts. Here, we demonstrate the unaltered in vitro recycling efficiencies of albumin conjugated to either a small chemical molecule or a peptide. Although various in vivo clearance mechanisms exist, these findings suggest that our recycling assay could be used as a screening tool of albumin-drug molecules for maintained FcRn affinity and recycling efficiency and, furthermore, demonstrate the potential benefits of albumin variants with improved FcRn-binding as a drug half-life extension technology.

In this work a panel of recombinant albumins with altered FcRn-binding affinities in combination with isogenic low and high FcRn-expressing HMEC-1 cells provided a unique tool kit to investigate the role of FcRn in the intracellular trafficking of albumin. The combination of flow cytometric and confocal microscopic analysis together with an in vitro cellular recycling investigation allowed direct evidence for the first time of an FcRn-mediated endocytotic recycling pathway that is vital to understanding albumin's pivotal role in endogenous ligand transport and utilization to tune the pharmacokinetics of albumin-based therapeutics.

Experimental procedures

Albumin production and labeling

HSA WT and albumin variants LB (with low-binding affinity to hFcRn; HSA K500A) and HB (with high-binding affinity to hFcRn; HSA K573P) were produced in yeast followed by a two-step purification using AlbuPure® matrix and diethylaminoethyl weak anion exchange Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) matrix as described previously (44). Alexa488, Alexa594, and 5FAM dyes with a maleimide-reactive group (Molecular Probes) were conjugated to albumin's Cys-34 free thiol residue. The conjugation reactions were performed in PBS (phosphate-buffered saline, Medicago, Sweden) at pH 7.1 at an ∼1:1.3 molar ratio (albumin to fluorescence-maleimide compound). The reaction was performed overnight at room temperature with gentle shaking, wrapped in foil to protect against light, and terminated by the addition of 0.5 volume WFI (water for injection) followed by a pH adjustment to 5.3 with acetic acid. The unreacted fluorescence-maleimide compound was removed by two cycles of concentration and dilution with WFI in VivaSpin-30. The conjugation was stabilized by hydrolysis (ring-opening) of the maleimide ring (45) by the addition of PBS and pH adjustment to 9.0. The hydrolysis was performed for 20 h at room temperature and terminated by neutralizing to pH 7.0. Because the overall yield after hydrolysis was ∼50%, the material was subjected to another cycle of conjugation and hydrolysis as described above. After the second round of hydrolysis, unreacted and hydrolyzed fluorescence-maleimide compound were removed by ultra/diafiltration in VivaSpin-30 with repeated cycles of concentration and dilution with PBS (pH 7.0).

The degree of labeling is estimated based on the manufacturer's instructions (46) using the following parameters: 5FAM (493 nm) ϵ = 68,000, CF280 = 0.3; Alexa488 (488 nm) ϵ = 73,000; CF280 = 0.11; Alexa594 ϵ = 92000, CF280 = 0.56.

FcRn-binding affinity was assessed by Biolayer Interferometry on an Octet Red96 system (Pall/Fortebio) to evaluate the binding integrity of the fluorescent albumins against human FcRn at pH 5.5 and 7.0 essentially as described previously (47).

Cell lines

Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC-1) (obtained from the Center for Disease Control) were cultured in MCDB131 medium (without l-glutamine) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma), 2 mm l-glutamine (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), 10 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Peprotech), 1 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor (Peprotech), 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma), and 0.25 μg/ml Fungizone (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. HMEC-1 cells were engineered to stably overexpress hFcRn (HMEC-1-FcRn) by lentiviral transduction (transduction performed by Sirion Biotech, Martinsried, Germany). In brief, HMEC-1 cells were transduced by replicative-deficient lentivirus bearing vectors with hFcRn and human β2-microglobulin sequences under the control of constitutive cytomegalovirus and the ubiquitin C promoters, respectively. Vector inclusion of neo and puro resistance genes enabled antibiotic selection using puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and G418 (Sigma).

Quantitative PCR

qPCR was performed to confirm the increased expression of FcRn in the engineered HMEC-1-FcRn cells. qPCR was carried out using a LightCycler480 (Roche Applied Science) using the LightCycler480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche Applied Science) reagent system. The sequences of the primers used were FcRn-Fw (5′-AAACCTGGAGTGGAAGGAGC) and FcRn-Rv (5′-GGTAGAAGGAGAAGGCGCTG) for amplification of FcRn expression and GAPDH-Fw (5′-GTCAGCCGCATCTTCTTTTG and GAPDH-Rv (5′-GCGCCCAATACGACCAAATC) for amplification of the reference gene GAPDH (DNA Technology, Risskov, Denmark).

Flow cytometric cellular uptake and trafficking studies

HMEC-1 and HMEC-1-FcRn cells were seeded in 48-well plates (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) at a density of 8.0 × 105 cells/well in complete HMEC-1 or complete HMEC-1-FcRn media in 0.5 ml for 24 h. Cells were exposed to 8 μm fluorescent albumin labeled with Alexa488 or 5FAM in a total volume of 125 μl of Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) without phenol red at pH 7.4 or adjusted with 1.0 m MES solution to pH 6.0 for 0.5–4 h followed by subsequent media removal and a 3× wash in ice-cold HBSS. Cells were harvested by trypsin treatment and centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4 °C followed by an additional wash, and cells were resuspended in 500 μl of sterile-filtrated PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% NaN3. For determination of albumin retention as an indicator of recycling, cells were exposed to 8 μm fluorescent albumin labeled with Alexa488 in a total volume of 125 μl of HBSS adjusted with 1 m MES solution to pH 6.0 for 2 h followed by subsequent media removal and 3× wash in ice-cold HBSS. Cells were then incubated for 1 or 2 h in HBSS (pH 7.4) before the cells were harvested by trypsin treatment and centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4 °C followed by an additional wash, and cells were resuspended in 500 μl of sterile-filtrated PBS flow buffer containing 2% BSA, 0.1% NaN3.

The samples were analyzed by flow cytometry using a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) equipped with a 488-nm laser and the 525/40-nm filter (FL1). All samples were measured before and after incubation with 20 μm monensin in 99.8% ethanol (VWR) for 10 min. Data were processed, and mean fluorescence intensity was determined using Kaluza 1.2 software (Beckman Coulter).

Transfection-based detection of endosomal/lysosomal localization by confocal microscopy of non-permeabilized cells

Cells were transfected with baculovirus (BacMam, Molecular Probes) for transient expression of GFP-fused Ras-related protein Rab-5 (Rab5) as an early endosome marker, Ras-related protein Rab-7a (Rab7) as a late endosome marker, and LAMP1 as a lysosome marker according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were transfected 24–48 h before the albumin uptake experiments. Alexa647-labeled dextran (Molecular Probes) was added to the cells 16 h before imaging at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml preceding the experiment, whereas cells were maintained in the cell culture incubator. Dextran media was replaced with fresh dextran-free media before imaging. Confocal images were captured using a Zeiss confocal microscope LSM 780 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena) equipped with lasers providing excitations at 488, 594, and 647 nm, a motorized xyz stage, and an incubator for temperature and CO2 control for live cell imaging. Images were captured using a Plan-Apochromat, 63 × NA 1.4, differential interference contrast (DIC) oil immersion objective. For Z-series, 0.24-μm slice spacing was used. All system settings were maintained identically for experiments where quantitative comparisons were performed.

Immunofluorescence detection of endosomal/lysosomal localization confocal microscopy of permeabilized cells

Rabbit primary antibodies for early endosomal antigen-1 (EEA1), Ras-related protein Rab-7a (RAB7A), and LAMP1 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Secondary goat anti-rabbit antibodies labeled with Alexa647 were purchased from Life Technologies. HBSS without phenol red, formalin, Dulbecco's PBS, Triton X-100, BSA, Hoechst 33342, (MES, NaN3, and monensin were purchased from Sigma.

Confocal images were captured using a Zeiss Confocal microscope LSM 700 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) equipped with lasers providing excitations at 405, 488, 555, and 647 nm, a motorized xyz stage. Images were captured using an alpha Plan-Apochromat, 100 ×/1.46 oil DIC M27 immersion objective. All system settings were maintained identically for experiments where quantitative comparisons were performed.

Image processing

Images were processed using Zeiss Zen Black 2012 edition. Whenever possible, signal saturation was avoided, and cells with saturated pixels were eliminated from analysis. Images shown in the figures were contrast-stretched to enhance the visibility of dim structures, but all images to be compared were contrast-enhanced identically. For quantification, the fluorescence signal in each image plane was corrected for background. A region of interest was drawn around individual cells, and the average pixel intensity was recorded for each fluorescent probe in the cell. Coefficients of co-localization were obtained from tri-dimensional images using Zen Black edition software package (Zeiss).

Cellular uptake of albumin

Uptake and co-localization of albumin with endosomal and lysosome markers was investigated using HMEC-1 and HMEC-1-FcRn cells overexpressing GFP-fused endocytic markers (non-permeabilized cells) or by staining the endogenous markers with fluorescently labeled antibodies (permeabilized cells). In both cases the cells were exposed to fluorescently labeled albumin compounds. Cells were seeded in tissue culture plates chambers (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, or Sarstedt) with coverslips to 80% cell confluency (0.8 × 106 cells/well). Cells were exposed to 8 μm fluorescent albumin in HBSS for 1–2 h before fixation. Upon removal of the media containing the albumins, the cells were washed 3× with ice-cold PBS and fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and mounted; alternatively, for antibody staining, the cells were fixed in 10% formalin followed by a 3× wash in PBS. Cells were permeabilized by incubation with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min followed by blocking in 5% BSA in PBS for 30 min. Cells were washed 3× and incubated with primary antibodies EEA1 (diluted 1:200), RAB7A (1:100), and LAMP1 (1:200) in PBS. Upon incubation with primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and followed by a 3× wash in PBS, the cells were then incubated with Alexa647-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody diluted to 4 μg/ml. Cells were incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature followed by a 3× wash in PBS. Actin filaments of the cells were stained by incubation with 0.5 units of ATTO565-labeled phalloidin (Atto-Tec, Siegen, Germany), diluted in 1% BSA in PBS for 20 min at room temperature, and followed by a 3× wash in PBS. The nuclei of the cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 diluted 1:2000 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature followed by a 3× wash in PBS.

Finally, the cells were mounted in fluorescent mounting media (Dako, Glostrup, DK) under a high precision coverglass (VWR) and sealed with transparent nail polish. Images were acquired using confocal microscopy as described above. For Alexa488-labeled albumin variants and GFP-fused markers (excitation (Ex), 488 nm; emissions (Em), 530/30), Hoechst 33342-stained nuclei (Ex, 405 nm; Em, 445/70), ATTO565-labeled phalloidin (Ex, 555 nm; Em, 580/40), Alexa647-labeled secondary antibodies and labeled albumins (Ex, 638; Em, 670/50) filter settings were used. Images were acquired with the same exposure times and laser power at all times.

Albumin cellular recycling assay

1 × 105 cells/well HMEC-1-FcRn cells were seeded in 48-well plates (Corning) precoated with GelTrex® (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the Thin Layer Method (non-gelling) coating procedure according to the manufactures protocol. The cells received fresh complete medium every other day and were cultured for at least 10 days to reach a confluent cell monolayer before experimental use. On the day of recycling, the cells were washed twice in prewarmed PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by the addition of 0.15 μm albumin (300 μl/well) in HBSS (Sigma) adjusted to pH 6.0 by 1 m MES buffer (Sigma). For recycling of immunoglobulins, cells were exposed to 0.07 μm IgG or IgY (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). After a 1-h incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2, the cells were washed 5 times in ice-cold PBS to remove all the extracellular albumin then received 160 μl/well complete medium without FBS and were incubated for another 1 h to allow recycling and release of internalized albumin. Finally, supernatants were collected and analyzed for albumin by ELISA.

ELISA detection of albumin and immunoglobulin G

In vitro recycled albumin was detected in a human albumin-specific sandwich ELISA. Maxisorp plates (Nunc) were coated overnight at 4 °C with a polyclonal goat anti-human albumin antibody (A-7544) (Sigma) (1:1000 diluted in PBS). Coated plates were blocked for 1 h with casein buffer (Sigma) before washing with PBS + 0.05% Tween and loading of the albumin standard and samples. Binding was allowed for 1 h followed by washing and incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary polyclonal sheep anti-human albumin antibody (ab8941) (Abcam) (1:5000 diluted in 10% casein buffer) for 1 h. After washing color reaction was achieved by 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (KemEnTec, Taastrup, Denmark), and enzymatic reactivity was stopped by H2SO4 before reading the plate at 450 nm.

Commercially available ELISA kits (GenWay Biotech) were used for measurement of human IgG (GWB-A04A50) and IgY (GWB-374Z14) and used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, supernatants were transferred to anti-IgY or anti-IgG antibody-coated plates and incubated at room temperature for 30 min (IgY) or 60 min (IgG). Enzyme-antibody conjugates were used for detection and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine was used for color development. Reaction was stopped with H2SO4, and plates were read at 450 nm.

Author contributions

K. A. H., J. C., and D. V. conceived the research. K. A. H., M. L. H., E. G. W. S., D. V., F. A., B. A., and N. N. K. planned the studies. E. G. W. S., M. L. H., F. A., J. C., B. A., and N. N. K. performed the experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data. K. A. H., M. L. H., E. G. W. S., and F. A. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S5.

- HSA

- human serum albumin

- FcRn

- neonatal Fc receptor

- hFcRn

- human FcRn

- HMEC

- human endothelial cell

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- LB

- low binder

- HB

- high binder

- 5FAM

- 5-carboxyfluorescein

- WFI

- water for injection

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- LAMP1

- lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1

- EEA1

- early endosomal antigen-1

- RAB7A

- Ras-related protein Rab-7a

- CF

- correction factor.

References

- 1. Peters T. (1996) All about Albumin: Biochemistry, Genetics, and Medical Applications. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaudhury C., Mehnaz S., Robinson J. M., Hayton W. L., Pearl D. K., Roopenian D. C., and Anderson C. L. (2003) The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan. J. Exp. Med. 197, 315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roopenian D. C., Christianson G. J., Sproule T. J., Brown A. C., Akilesh S., Jung N., Petkova S., Avanessian L., Choi E. Y., Shaffer D. J., Eden P. A., and Anderson C. L. (2003) The MHC class I-like IgG receptor controls perinatal IgG transport, IgG homeostasis, and fate of IgG-Fc-coupled drugs. J. Immunol. 170, 3528–3533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ward E. S., Zhou J., Ghetie V., and Ober R. J. (2003) Evidence to support the cellular mechanism involved in serum IgG homeostasis in humans. Int. Immunol. 15, 187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chaudhury C., Brooks C. L., Carter D. C., Robinson J. M., and Anderson C. L. (2006) Albumin binding to FcRn: distinct from the FcRn-IgG interaction. Biochemistry 45, 4983–4990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andersen J. T., Dalhus B., Cameron J., Daba M. B., Plumridge A., Evans L., Brennan S. O., Gunnarsen K. S., Bjørås M., Sleep D., and Sandlie I. (2012) Structure-based mutagenesis reveals the albumin-binding site of the neonatal Fc receptor. Nat. Commun 3, 610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andersen J. T., Dalhus B., Viuff D., Ravn B. T., Gunnarsen K. S., Plumridge A., Bunting K., Antunes F., Williamson R., Athwal S., Allan E., Evans L., Bjørås M., Kjærulff S., Sleep D., Sandlie I., and Cameron J. (2014) Extending serum half-life of albumin by engineering neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) binding. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 13492–13502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ehrhardt C., and Kim K. J. (2008) Drug Absorption Studies: in Situ, in Vitro, and in Silico Models, pp. 640–662, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dickinson B. L., Badizadegan K., Wu Z., Ahouse J. C., Zhu X., Simister N. E., Blumberg R. S., and Lencer W. I. (1999) Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 903–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maunsbach A. B. (1966) Albumin absorption by renal proximal tubule cells. Nature 212, 546–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maunsbach A. B. (1966) Absorption of I-125-labeled homologous albumin by rat kidney proximal tubule cells: a study of microperfused single proximal tubules by electron microscopic autoradiography and histochemistry. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 15, 197–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park C. H., and Maack T. (1984) Albumin absorption and catabolism by isolated perfused proximal convoluted tubules of the rabbit. J. Clin. Invest. 73, 767–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Russo L. M., Sandoval R. M., McKee M., Osicka T. M., Collins A. B., Brown D., Molitoris B. A., and Comper W. D. (2007) The normal kidney filters nephrotic levels of albumin retrieved by proximal tubule cells: retrieval is disrupted in nephrotic states. Kidney Int. 71, 504–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tenten V., Menzel S., Kunter U., Sicking E. M., van Roeyen C. R., Sanden S. K., Kaldenbach M., Boor P., Fuss A., Uhlig S., Lanzmich R., Willemsen B., Dijkman H., Grepl M., Wild K., Kriz W., et al. (2013) Albumin is recycled from the primary urine by tubular transcytosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24, 1966–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Birn H., Fyfe J. C., Jacobsen C., Mounier F., Verroust P. J., Orskov H., Willnow T. E., Moestrup S. K., and Christensen E. I. (2000) Cubilin is an albumin binding protein important for renal tubular albumin reabsorption. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1353–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amsellem S., Gburek J., Hamard G., Nielsen R., Willnow T. E., Devuyst O., Nexo E., Verroust P. J., Christensen E. I., and Kozyraki R. (2010) Cubilin is essential for albumin reabsorption in the renal proximal tubule. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 1859–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verroust P. J., and Christensen E. I. (2002) Megalin and cubilin-the story of two multipurpose receptors unfolds. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 17, 1867–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Predescu D., Vogel S. M., and Malik A. B. (2004) Functional and morphological studies of protein transcytosis in continuous endothelia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 287, L895–L901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carson J. M., Okamura K., Wakashin H., McFann K., Dobrinskikh E., Kopp J. B., and Blaine J. (2014) Podocytes degrade endocytosed albumin primarily in lysosomes. PloS ONE 9, e99771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brülisauer L., Valentino G., Morinaga S., Cam K., Thostrup Bukrinski J., Gauthier M. A., and Leroux J. C. (2014) Bio-reduction of redox-sensitive albumin conjugates in FcRn-expressing cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 8392–8396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andersen J. T., Dee Qian J., and Sandlie I. (2006) The conserved histidine 166 residue of the human neonatal Fc receptor heavy chain is critical for the pH-dependent binding to albumin. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 3044–3051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oganesyan V., Damschroder M. M., Cook K. E., Li Q., Gao C., Wu H., and Dall'Acqua W. F. (2014) Structural insights into neonatal Fc receptor-based recycling mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 7812–7824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ober R. J., Martinez C., Lai X., Zhou J., and Ward E. S. (2004) Exocytosis of IgG as mediated by the receptor, FcRn: an analysis at the single-molecule level. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 11076–11081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ward E. S., Martinez C., Vaccaro C., Zhou J., Tang Q., and Ober R. J. (2005) From sorting endosomes to exocytosis: association of Rab4 and Rab11 GTPases with the Fc receptor, FcRn, during recycling. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 2028–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gan Z., Ram S., Vaccaro C., Ober R. J., and Ward E. S. (2009) Analyses of the recycling receptor, FcRn, in live cells reveal novel pathways for lysosomal delivery. Traffic. 10, 600–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weflen A. W., Baier N., Tang Q. J., Van den Hof M., Blumberg R. S., Lencer W. I., and Massol R. H. (2013) Multivalent immune complexes divert FcRn to lysosomes by exclusion from recycling sorting tubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 2398–2405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schultze H. E., and Heremans J. F. (1966) Molecular Biology of Human Proteins, with Special Reference to Plasma Proteins. Elsevier Pub. Co., New York [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brambell F. W. R. (1970) The Transmission of Passive Immunity from Mother to Young, pp. 1–385, North-Holland Publishing Co., American Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borvak J., Richardson J., Medesan C., Antohe F., Radu C., Simionescu M., Ghetie V., and Ward E. S. (1998) Functional expression of the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, in endothelial cells of mice. Int. Immunol. 10, 1289–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akilesh S., Christianson G. J., Roopenian D. C., and Shaw A. S. (2007) Neonatal FcR expression in bone marrow-derived cells functions to protect serum IgG from catabolism. J. immunol. 179, 4580–4588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mellman I. (1996) Endocytosis and molecular sorting. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 575–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schnitzer J. E., and Bravo J. (1993) High affinity binding, endocytosis, and degradation of conformationally modified albumins: potential role of gp30 and gp18 as novel scavenger receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 7562–7570 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schnitzer J. E., Sung A., Horvat R., and Bravo J. (1992) Preferential interaction of albumin-binding proteins, gp30 and gp18, with conformationally modified albumins: presence in many cells and tissues with a possible role in catabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 24544–24553 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schnitzer J. E., and Oh P. (1994) Albondin-mediated capillary permeability to albumin: differential role of receptors in endothelial transcytosis and endocytosis of native and modified albumins. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 6072–6082 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Claypool S. M., Dickinson B. L., Yoshida M., Lencer W. I., and Blumberg R. S. (2002) Functional reconstitution of human FcRn in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells requires co-expressed human beta 2-microglobulin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28038–28050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Claypool S. M., Dickinson B. L., Wagner J. S., Johansen F. E., Venu N., Borawski J. A., Lencer W. I., and Blumberg R. S. (2004) Bidirectional transepithelial IgG transport by a strongly polarized basolateral membrane Fcγ-receptor. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1746–1759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tzaban S., Massol R. H., Yen E., Hamman W., Frank S. R., Lapierre L. A., Hansen S. H., Goldenring J. R., Blumberg R. S., and Lencer W. I. (2009) The recycling and transcytotic pathways for IgG transport by FcRn are distinct and display an inherent polarity. J. Cell Biol. 185, 673–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu X., Ye L., Christianson G. J., Yang J. Q., Roopenian D. C., and Zhu X. (2007) NF-kappaB signaling regulates functional expression of the MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor for IgG via intronic binding sequences. J. Immunol. 179, 2999–3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leitner K., Ellinger I., Grill M., Brabec M., and Fuchs R. (2006) Efficient apical IgG recycling and apical-to-basolateral transcytosis in polarized BeWo cells overexpressing hFcRn, Placenta 27, 799–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tesar D. B., Tiangco N. E., and Bjorkman P. J. (2006) Ligand valency affects transcytosis, recycling and intracellular trafficking mediated by the neonatal Fc receptor. Traffic 7, 1127–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xie D., Yao C., Wang L., Min W., Xu J., Xiao J., Huang M., Chen B., Liu B., Li X., and Jiang H. (2010) An albumin-conjugated peptide exhibits potent anti-HIV activity and long in vivo half-life. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 54, 191–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu Y. L., Huang J., Xu J., Liu J., Feng Z., Wang Y., Lai Y., and Wu Z. R. (2010) Addition of a cysteine to glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) conjugates GLP-1 to albumin in serum and prolongs GLP-1 action in vivo. Regul. Pept. 164, 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baggio L. L., Huang Q., Cao X., and Drucker D. J. (2008) An albumin-exendin-4 conjugate engages central and peripheral circuits regulating murine energy and glucose homeostasis. Gastroenterology 134, 1137–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Evans L., Hughes M., Waters J., Cameron J., Dodsworth N., Tooth D., Greenfield A., and Sleep D. (2010) The production, characterisation and enhanced pharmacokinetics of scFv-albumin fusions expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr. Purif. 73, 113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith M. E., Caspersen M. B., Robinson E., Morais M., Maruani A., Nunes J. P., Nicholls K., Saxton M. J., Caddick S., Baker J. R., and Chudasama V. (2015) A platform for efficient, thiol-stable conjugation to albumin's native single accessible cysteine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 7946–7949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnson I. (2010) Molecular Probes Handbook: A Guide to Fluorescent Probes and Labeling Technologies. 11th Ed., ThermoFisher Scientific [Google Scholar]

- 47. Viuff D., Antunes F., Evans L., Cameron J., Dyrnesli H., Thue Ravn B., Stougaard M., Thiam K., Andersen B., Kjærulff S., and Howard K. A. (2016) Generation of a double transgenic humanized neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)/albumin mouse to study the pharmacokinetics of albumin-linked drugs. J. Control Release 223, 22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.