Abstract

Constitutive WNT activity drives the growth of various human tumors, including nearly all colorectal cancers (CRCs). Despite this prominence in cancer, no WNT inhibitor is currently approved for use in the clinic largely due to the small number of druggable signaling components in the WNT pathway and the substantial toxicity to normal gastrointestinal tissue. We have shown that pyrvinium, which activates casein kinase 1α (CK1α), is a potent inhibitor of WNT signaling. However, its poor bioavailability limited the ability to test this first-in-class WNT inhibitor in vivo. We characterized a novel small-molecule CK1α activator called SSTC3, which has better pharmacokinetic properties than pyrvinium, and found that it inhibited the growth of CRC xenografts in mice. SSTC3 also attenuated the growth of a patient-derived metastatic CRC xenograft, for which few therapies exist. SSTC3 exhibited minimal gastrointestinal toxicity compared to other classes of WNT inhibitors. Consistent with this observation, we showed that the abundance of the SSTC3 target, CK1α, was decreased in WNT-driven tumors relative to normal gastrointestinal tissue, and knocking down CK1α increased cellular sensitivity to SSTC3. Thus, we propose that distinct CK1α abundance provides an enhanced therapeutic index for pharmacological CK1α activators to target WNT-driven tumors.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most prevalent cancer in the United States (1), with ~50,000 CRC patients succumbing to their disease each year. The poor outcome of these patients underscores the urgent need for more effective CRC therapies. This need is especially great for patients harboring metastatic CRC, only 13% of whom survive beyond 5 years and for whom few targeted therapies exist (1). The mechanisms underlying the genesis and progression of CRC are now well established (2). Mutations in genes encoding components of the WNT signaling pathway (APC, which encodes adenomatous polyposis coli, and CTNNB1, which encodes β-catenin) were identified as early events in the vast majority of all CRCs, followed by mutations in additional oncogenic drivers such as KRAS and P53 (2, 3). More advanced stages of CRC remain addicted to WNT signaling (4), including metastasis (5). Despite the well-established mechanistic paradigm implicating WNT signaling in the development and progression of CRC, no WNT inhibitors are currently approved for clinical use.

The critical event in WNT signaling is the posttranslational regulation of the transcriptional coactivator β-catenin. In the absence of a WNT ligand, cytoplasmic β-catenin is maintained at low levels because of its constitutive degradation. This degradation occurs primarily via its association with a “destruction complex,” which consists of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), casein kinase 1α (CK1α), APC, and AXIN (6). The rate-limiting component in this complex is the scaffold protein AXIN, whose steady-state levels are tightly controlled by the adenosine diphosphate–ribose polymerase, tankyrase, targeting AXIN for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (7). All WNTs are palmitoylated in the endoplasmic reticulum by the membrane-bound O-acetyltransferase protein, Porcupine (8, 9). Post-translational modification of WNTs by palmitoylation is necessary for their exit from the endoplasmic reticulum and binding to Frizzled receptors (10–12). Upon Frizzled and co-receptor (LRP6) binding, β-catenin degradation is inhibited, and AXIN is ultimately degraded (13–16). In turn, β-catenin is translocated to the nucleus where it interacts with a variety of nuclear transcriptional regulators, such as BCL9 and PYGOPUS, to activate a T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer binding factor–mediated transcriptional program (17–20).

One emerging class of WNT inhibitors currently in clinical trials, Porcupine inhibitors, acts by blocking the palmitoylation of WNT ligands (21, 22). However, these inhibitors will likely not prove useful to target CRCs because the constitutive WNT activity driving CRC is ligand-independent. A second important class of WNT inhibitors is small-molecule Tankyrase inhibitors (TANKi) (7). Because tankyrase inhibition can attenuate the nonligand-driven WNT activity commonly found in CRC cells, such inhibitors represent a promising targeted therapeutic in CRC therapy (23). A significant hurdle to the clinical development of WNT inhibitors is overcoming the on-target toxicity that results from effects on the WNT-dependent intestinal stem cells that drive normal gastrointestinal (GI) homeostasis (24, 25). Such dose-limiting on-target toxicities have been observed using both Tankyrase and Porcupine inhibitors (23, 26, 27), with continuous dosing of both classes of small molecules disrupting normal GI structure and function. Thus, there appears to be only a limited therapeutic window for Porcupine and TANKi, which might ultimately limit their clinical utility.

We previously described a mechanistically distinct WNT inhibitor, pyrvinium, which was already Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved as an anthelmintic agent (28, 29). We showed that pyrvinium potently attenuated WNT activity by binding and activating CK1α. Pyrvinium also potently reduced the viability of CRC cell lines in culture, consistent with it attenuating WNT activity downstream of the common mutations that drive CRC growth. However, pyrvinium’s limited bioavailability precluded testing its efficacy against CRC growth in vivo and thus reduced its potential clinical utility as a WNT inhibitor for CRC patients (30, 31). Here, we sought to identify and characterize a second-generation CK1α activator with improved bioavailability, which would allow us to determine its efficacy against WNT-driven cancers in vivo.

RESULTS

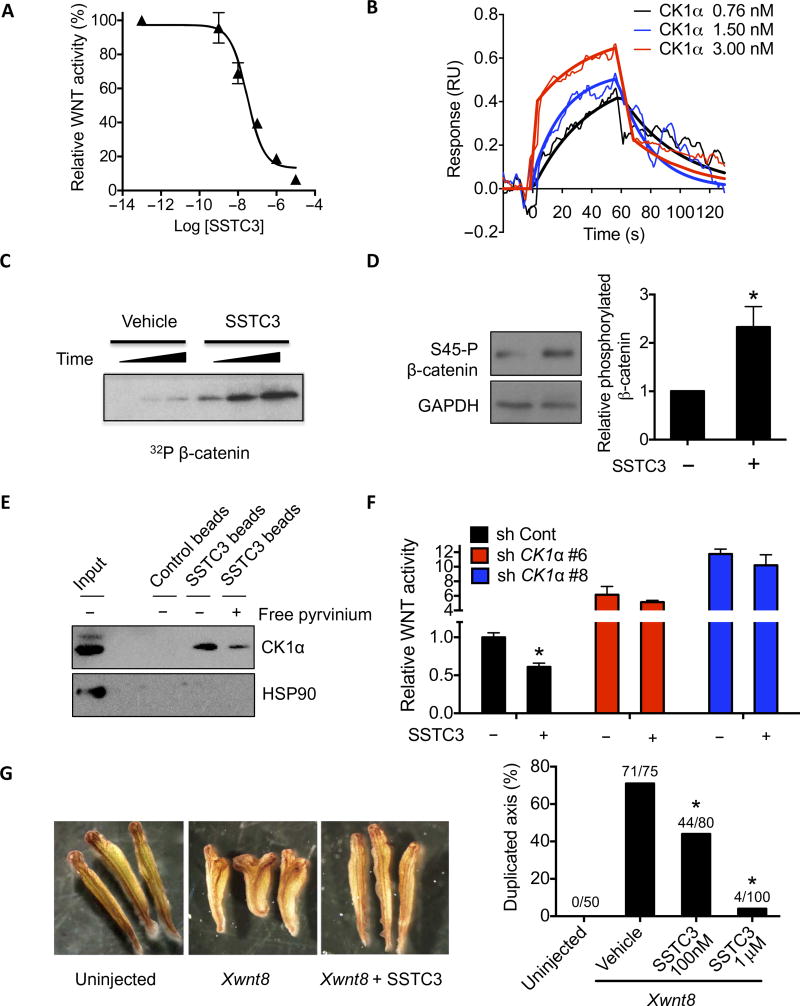

Activation of CK1α by SSTC3 inhibits WNT signaling

To identify a CK1α activator with the pharmacokinetic properties necessary to advance into the clinic, we used an in silico scaffold screening approach (32). These scaffolds were prioritized on the basis of their predicted physical and pharmacokinetic properties and subsequently tested for their ability to attenuate a WNT-driven reporter gene assay. Subsequent cycles of medicinal chemistry and assaying WNT reporter gene activity led to the identification of SSTC3 (fig. S1A). SSTC3 attenuated the activity of a WNT reporter gene in a potent, dose-dependent manner [median effective concentration (EC50) = 30 nM; Fig. 1A] and bound directly to purified recombinant CK1α with a similar binding constant (Kd = 32 nM; Fig. 1B). SSTC3 treatment rapidly enhanced phosphorylation of CK1α substrates in vitro and in SW403 cells (Fig. 1, C and D). Further, SSTC3 coupled agarose beads associated with cellular CK1α (Fig. 1E and fig. S1B), and this association was reversible in the presence of uncoupled SSTC3 (fig. S1B) or pyrvinium (Fig. 1E). SSTC3 also attenuated WNT reporter activity (Fig. 1F) in a manner dependent on CK1α-dependent manner (fig. S1C). Injection of SSTC3 into Xenopus laevis embryos inhibited the ability of exogenous WNT to induce a secondary body axis (Fig. 1G), a classic WNT-driven phenotype (33), consistent with SSTC3 attenuating WNT signaling in vivo. Together, these results suggest that SSTC3 inhibits WNT signaling via activation of CK1α in a manner similar to that of pyrvinium.

Fig. 1. A novel CK1α activator attenuates WNT signaling.

(A) A TOPflash WNT reporter assay in 293T cells using the indicated doses of SSTC3 in the presence of WNT3A. A representative figure is shown (means ± SD, n = 3). (B) SSTC3 was covalently immobilized to the surface of a CM5 sensor chip, and SPR sensorgrams were generated by flowing the indicated concentrations of recombinant CK1α over it. Representative data are shown (n = 3). RU, resonance units. (C) CK1α was incubated with recombinant β-catenin plus vehicle or SSTC3 (100 nM) in a kinase reaction containing [γ32P]–adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for 0.5, 1, or 3 min, followed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. (D) SW403 cells were treated with 100 nM SSTC3 for 15 min, and the Ser45 phosphorylation status of β-catenin was determined by immunoblotting. A representative image (left) and quantification (means ± SEM; right) of three independent experiments is shown (Student’s t test, *P ≤ 0.05). (E) SSTC3-coupled agarose beads were used to isolate endogenous CK1α from 293T cell lysates in the presence or absence of free pyrvinium, followed by analysis of the indicated proteins by immunoblotting. (F) HCT116 cells expressing the indicated short hairpin RNA (shRNA) were transfected with the TOPflash reporter and treated with SSTC3 (100 nM) or vehicle. Luciferase activity was determined 48 hours later. Data are means ± SEM (n = 3; Student’s t test, *P ≤ 0.05). (G) Four- to eight-cell stage embryos were injected ventrally with Xwnt8 mRNA (1 pg) plus vehicle or SSTC3 (100 nM or 1 µM), allowed to develop, and scored for secondary axis formation (Fisher’s exact test, *P ≤ 0.05).

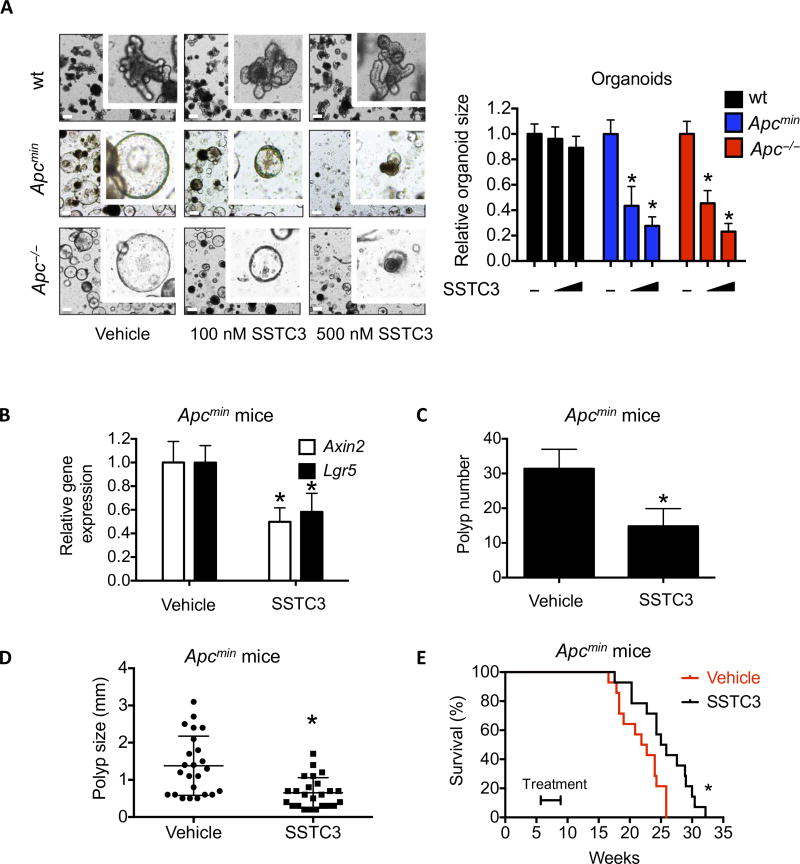

Activation of CK1α inhibits Apc mutation-driven tumor growth

Loss of the tumor suppressor Apc leads to sustained activation of WNT signaling and intestinal adenoma formation in various mouse models (34–36). Organoids derived from these adenomas can be isolated and grown in a minimal culture that requires endogenous WNT activity (37). SSTC3 attenuated the growth of such Apc mutant organoids in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A and fig. S2A). Notably, we observed that the EC50 of SSTC3 in wild-type organoids (2.9 µM) was significantly higher than that in Apc mutant organoids (150 nM for Apc−/− and 70 nM for Apcmin) (Fig. 2A and fig. S2A). The expression of WNT target genes, Axin2 and the crypt stem cell marker Lgr5, in the intestines of Apcmin mice were also reduced upon acute treatment with SSTC3 in vivo (Fig. 2B). Consistent with this reduced WNT activity in vivo, chronic exposure of Apcmin mice to SSTC3 reduced both the numbers and average size of their intestinal polyps (Fig. 2,C and D). The life span of Apcmin mice is reduced relative to wild-type mice because of bleeding complications secondary to polyp growth (38, 39). Given this reduction in polyp size and numbers, SSTC3 treatment provided an increased survival advantage to such mice (Fig. 2E). Thus, SSTC3 attenuates WNT signaling–driven polyp growth in vivo, and this decreased activity leads to prolonged survival of a commonly used mouse intestinal tumor model.

Fig. 2. SSTC3 inhibits the growth of Apc mutation-driven tumors.

(A) Organoids derived from wild-type (wt) mouse intestine or Apc mutant tumors were treated with the indicated doses of SSTC3 for 4 days. Representative images (left) or quantification of organoid size (diameter) from four independent replicates (right) are shown. Data are means ± SEM (Student’s t test, *P ≤ 0.05). Scale bars, 200 µm. (B) Apcmin mice were dosed with SSTC3 [10 mg/kg intraperitoneally (ip)] or vehicle, and the small intestines were subsequently harvested and analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Data are means ± SEM (n = 4 in control group and 5 in treatment group; Student’s t test, *P ≤ 0.05). (C and D) Apcmin mice were treated with vehicle or SSTC3 (10 mg/kg ip) for 1 month, dosing every other day. Polyp number (C) and size (D) were quantitated. Data are means ± SEM (n = 5 mice in each group; Student’s t test, *P ≤ 0.05). (E) Five-week-old Apcmin mice were treated with vehicle or SSTC3 (10 mg/kg ip) (n = 14 for each group) for 1 month as indicated, dosing every other day. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of these mice are shown, which was determined using a log-rank Mantel-Cox test (*P ≤ 0.05).

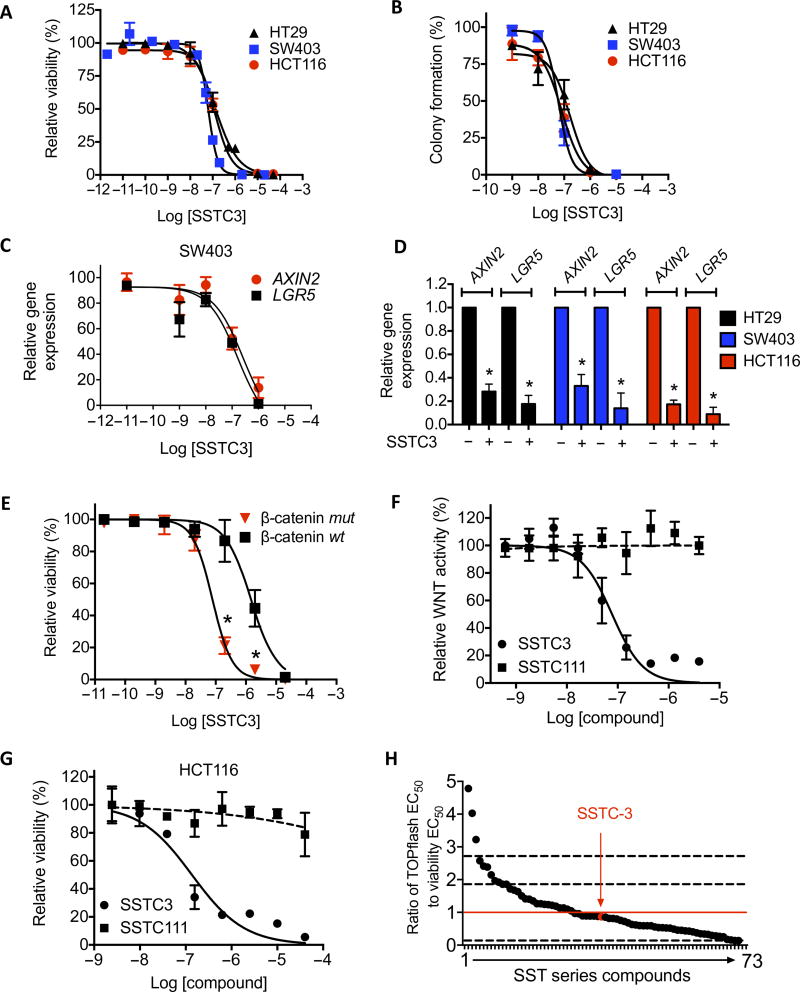

Activation of CK1α inhibits the growth of WNT activity–dependent CRC cell lines

To extend our findings to CRC, we treated CRC cell lines with different doses of SSTC3, two whose growth are driven by APC mutations (SW403 and HT29 cells), one whose growth is driven by a mutation in the β-catenin gene CTNNB1 (HCT116 cells), and one that is not WNT-dependent (RKO cells). The viability of the WNT-dependent cell lines decreased in a dose-dependent manner (EC50 = 132, 63, and 123 nM for HT29, SW403, and HCT116 cells, respectively; Fig. 3A), as was their ability to form individual colonies (EC50 = 168, 61, and 80 nM for HT29, SW403, and HCT116 cells, respectively; Fig. 3B), whereas RKO cells were significantly less sensitive to SSTC3 (EC50 = 3.1 µM; fig. S2B). We noted that the EC50 doses of SSTC3 for attenuating WNT reporter activity, CRC cell viability, and the expression of two WNT target genes (EC50 = 100 nM for AXIN2 and 106 nM for LGR5; Fig. 3C) were comparable to its binding affinity for CK1α (Fig. 1B). Further, SSTC3 exposure resulted in reduced expression of WNT target genes in all three sensitive CRC cell lines (Fig. 3D). The capacity of SSTC3 to decrease the viability of HCT116 cells was also significantly reduced when the mutant CTNNB1 allele driving its carcinogenic properties was deleted (EC50 = 78 nM versus 1.5 µM; Fig. 3E). Furthermore, an inactive structural analog of SSTC3, SST111 (fig. S1A and Fig. 3F), had minimal effects on CRC cell viability (Fig. 3G) or WNT target gene expression (fig. S3, A and B). Finally, we determined the ability of a series of structurally distinct SSTC3 derivatives to reduce WNT activity in a reporter assay and to attenuate HCT116 cell viability, deriving a ratio of each compound’s EC50 in both of these assays as an indicator of its on-target effects on viability (Fig. 3H). We found that, although the EC50 range for these SSTC3 derivatives varied about 100-fold, 90% of them exhibited an EC50 ratio within 1 SD of the idealized EC50 ratio of 1. Together, these results suggest that SSTC’s effect on CRC viability is primarily through an on-target mechanism, the attenuation of WNT activity.

Fig. 3. SSTC3 reduces the viability of colorectal carcinoma cells in an on-target manner.

(A and B) Viability (A) and colony formation (B) in CRC cells treated with SSTC3 for 5 days. (C) Expression of the indicated genes analyzed by qRT-PCR in SW403 cells treated with SSTC3 (as indicated) for 4 days analyzed by qRT-PCR. (D) Expression of the indicated genes analyzed by qRT-PCR in the indicated cells treated with vehicle or SSTC3 (2 µM) for 2 days. (E) Cell viability in β-catenin–mutant (mut) or wt HCT116 cells treated with a range of doses of SSTC3 for 5 days. (F) WNT reporter activity was determined in 293T cells using the indicated compounds and doses. (G) Cell viability in HCT116 cells treated with the indicated compounds for 72 hours. (H) Ratio of suppression of WNT reporter expression (drug activity range, 18nM to 2.3 µM) in 293T cells to suppression of cell viability in HCT116 cells (drug activity range, 41 nM to 3.9 µM) by SSTC3 derivatives. Red line indicates an idealized ratio of 1. Dashed lines indicate 1 SD from the ratio of SSTC3. Data are means ± SEM from n = 3 experiments (A to E) and means ± SD from a representative of multiple independent experiments (F and G) (*P ≤ 0.05).

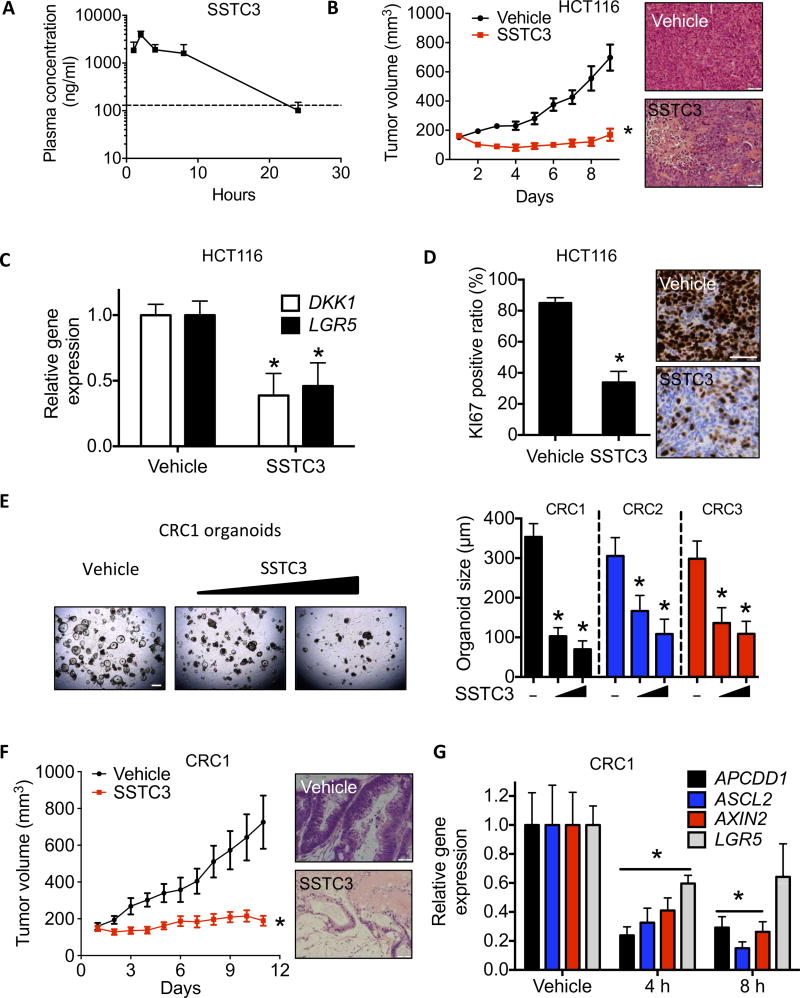

Activation of CK1α inhibits growth of a patient-derived CRC xenograft

We injected SSTC3 into CD-1 mice and measured the plasma concentration by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) at five time points over 24 hours. On the basis of escalating doses in nude mice, a strong dose-dependent correlation of both maximal concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) for SSTC3 was obtained in the serum. Our data show that ~250 nM concentration of SSTC3 can be maintained for 24 hours after treatment (Fig. 4A). This result verifies that the pharmacokinetic properties of SSTC3 are significantly improved over that of pyrvinium (31). Taking advantage of the improved pharmacokinetic properties of SSTC3, we tested for the first time the capacity of a CK1α activator to attenuate the growth of CRC in vivo. SSTC3 significantly inhibited the growth of HCT116 xenografts, compared to the vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 4B). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the residual tumor samples showed substantial loss of cancer cells in the SSTC3-treated group (Fig. 4B and fig. S4A). The reduction of both WNT target gene expression (Fig. 4C) and the proliferation marker KI67 (Fig. 4D) was also observed in the tumors exposed to SSTC3. We obtained a panel of patient-derived CRC samples, two of which contained common APC mutations (CRC1 and CRC2), and established organoid cultures from them. SSTC3 treatment significantly reduced the growth of all three patient-derived CRC organoid cultures (Fig. 4E), relative to those treated with vehicle. One of these APC mutant CRCs, derived from a lung metastasis, was also used to establish patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) in mice. SSTC3 attenuated the growth of this metastatic CRC PDX (Fig. 4F) and markedly reduced the cell density of residual cancer (Fig. 4F and fig. S4B). SSTC3 also reduced the expression of WNT biomarkers in this CRC PDX (Fig. 4G), consistent with it acting in an on-target manner.

Fig. 4. SSTC3 suppresses the growth of colorectal carcinoma in vivo.

(A) Plasma concentration of SSTC3 in CD-1 mice after intraperitoneal injection. Data are means ± SD (n = 3; dashed line, 250 nM). (B) Tumor volume (left) and H&E staining (right) of HCT116 xenografts in mice treated with vehicle or SSTC3 (25 mg/kg ip) for the indicated days (n = 10 in each group). Scale bars, 100 µm. (C and D) WNT-associated gene expression by qRT-PCR (C; n = 7 mice per group) and KI67 staining (D) in residual tumors from mice described in (B) (n = 6 mice per group). Scale bar, 50 µm. (E) Representative image showing organoids derived from a patient’s CRC (CRC1) treated with vehicle or SSTC3 (200 nM and 2 µM, respectively) for 7 days is shown (left). Scale bar, 500 µm. The diameter of organoid cultures (n = 12 separate cultures) derived from three distinct resected patient CRCs was quantitated (right). (F) Tumor growth in PDXs (CRC1) from mice treated with SSTC3 (15 mg/kg ip daily) or vehicle (n = 10 and 9 mice, respectively). Right: Representative H&E staining. Scale bar, 100 µm. (G) qRT-PCR analysis in CRC1 tumors from mice treated with SSTC3 (15 mg/kg) or vehicle (n = 5 each). Data are means ± SEM (Student’s t test, *P ≤ 0.05).

CK1α activation does not inhibit the proliferation of intestinal epithelium cells in vivo

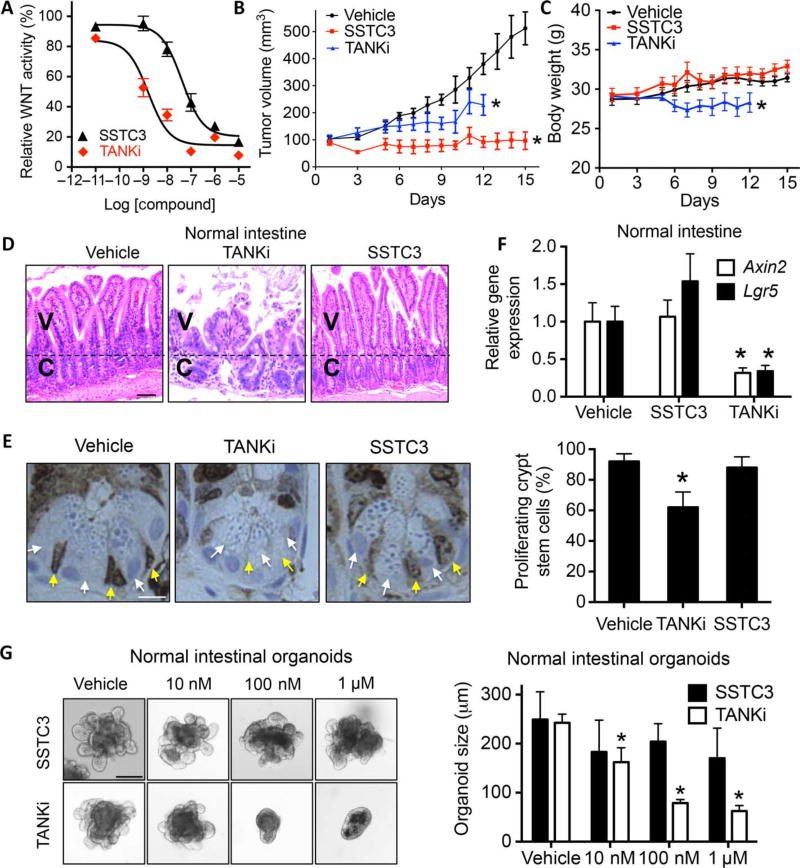

One hurdle to the clinical development of WNT inhibitors is the on-target GI toxicity observed upon chronic dosing in animal models. Notably, mice exposed to either of two structurally distinct CK1α activators did not exhibit the weight loss typical of chronic effects on GI homeostasis [fig. S5, A and B, and (29)]. To explore this unexpected observation further, we directly compared the biological effects of SSTC3 to that of a TANKi (G007-LK) reported to disrupt normal GI physiology (23). We first compared their potency using a WNT reporter gene assay and noted that the TANKi was about 20 times more potent than SSTC3 in reducing ligand-induced WNT signaling (Fig. 5A). We next compared the activity of each of these WNT inhibitors on tumor growth and GI homeostasis within the same mice. For this experiment, we implanted an APC mutant CRC cell line (SW403), previously reported to be sensitive to TANKi (23), into the flanks of nude mice. Both WNT inhibitors significantly reduced the growth of the CRC xenograft (Fig. 5B), with SSTC3 exhibiting greater efficacy than the TANKi. Because the average body weight of TANKi-treated mice declined significantly and a number of the mice became moribund, we stopped this treatment after 12 days (Fig. 5C). However, the body weight of the SSTC3-treated mice remained similar to vehicle-treated mice. Sections of the mouse intestine were obtained from treated mice, H&E-stained, and examined by a pathologist. Although the crypt/villus axes of TANKi-treated mice were severely disrupted, only minor differences in the intestinal tissue were observed between SSTC3- and vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 5D and fig. S5, C and D). Consistent with this finding, TANKi treatment disrupted the proliferation of WNT-dependent intestinal crypt base columnar cells, whereas SSTC3 did not (Fig. 5E). We next examined the ability of the two WNT inhibitors to attenuate the expression of WNT biomarkers in the intestines of nontumor-bearing mice, when acutely exposed to either inhibitor at doses capable of reducing CRC growth. The expression of Axin2 and Lgr5 were substantially reduced in the intestinal tissue of nontumor-bearing mice treated with TANKi, whereas SSTC3 exposure had no observable effects on their expression (Fig. 5F). Thus, the limited effects of SSTC3 on GI homeostasis were observed in both tumor- and nontumor-bearing mice. Comparing the two WNT inhibitors in vivo is likely complicated by differences in their pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics. Therefore, to more directly compare their effects on GI homeostasis, we took advantage of established procedures to grow and maintain mouse intestinal tissue as enteroids, which are composed of villi and primitive cryptlike intestinal stem cell compartments (40). Similar to what was observed in vivo, SSTC3 had little effect on intestinal crypt/villus structures ex vivo (Fig. 5G), whereas the TANKi severely attenuated their growth.

Fig. 5. SSTC3 exhibits efficacy with minimal GI toxicity.

(A) TOPflash WNT reporter assay in 293T cells cultured with the indicated doses of SSTC3 and G007-LK (TANKi) in the presence of WNT3A. Representative data are shown (means ± SD, n = 3). (B) SW403 xenograft growth in mice treated with SSTC3 (15 mg/kg ip) or TANKi (40 mg/kg ip) for the indicated days (n = 7 in each group). (C to E) Body weight in mice (C) and representative H&E (D) and KI67 staining of mouse intestines (E) after treatment as described in (B). V, villi; C, crypt. Yellow and white arrows indicate crypt base columnar and paneth cells, respectively. Quantitative analysis of 120 crypts from four separate mice is shown (right) (E). Scale bars, 50 µm (D) and 10 µm (E). (F) qRT-PCR analysis on intestines from nude mice treated with vehicle, TANKi (40 mg/kg), or SSTC3 (15 mg/kg) (n = 4 in each group). (G) Size of wt organoids after 5-day treatment with vehicle or the indicated doses of SSTC3 or TANKi. Left: Representative images. Right: Quantification of mean size from five independent cultures. Scale bar, 100 µm. Data are means ± SEM (Student’s t test, *P ≤ 0.05).

WNT activity regulates CK1α levels, modulating SSTC3 sensitivity

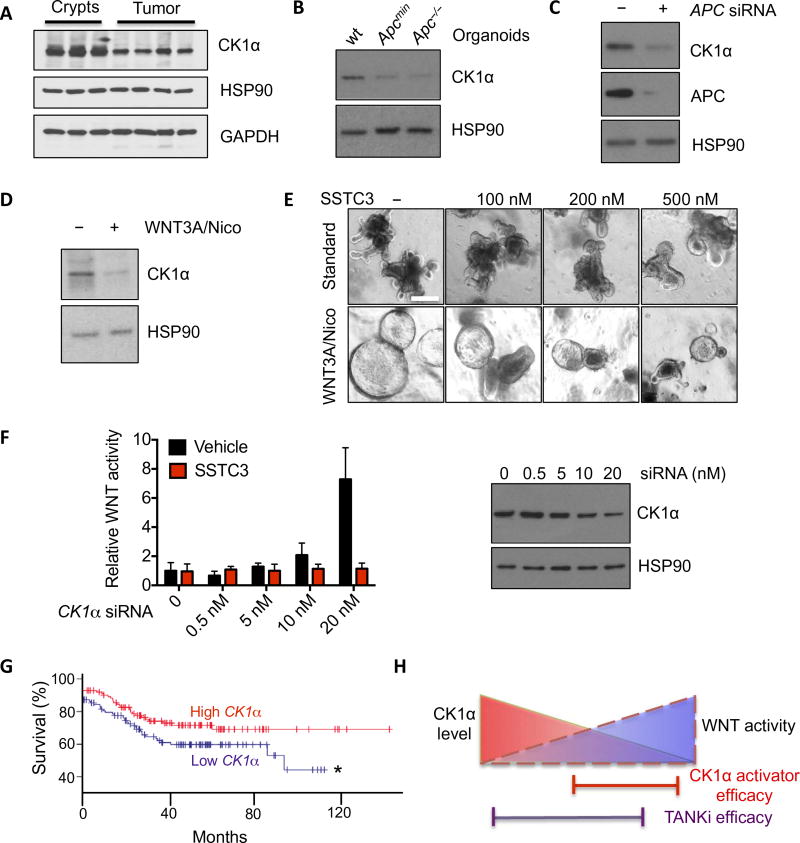

CK1α is an established negative regulator of the WNT signaling pathway, whose deficiency leads to hyperactivated WNT signaling, and contributes to metastatic CRC in mouse models (41). Thus, we hypothesized that the differential SSTC3 response we observe in tumor tissue, relative to normal intestinal tissue, results from distinct amounts of its cellular target, CK1α. To begin to test this hypothesis, we compared the abundance of CK1α in isolated intestinal crypts and tumors from Apcmin mice by immunoblotting and observed a 40% decrease in CK1α abundance in tumor tissue relative to normal intestinal crypts (Fig. 6A and fig. S6A). Similar differences were found in organoids derived from these tissues (Fig. 6B and fig. S6B). Knockdown of APC in 293T cells also resulted in decreased abundance of CK1α (Fig. 6C and fig. S6C), consistent with the notion that activation of WNT signaling negatively regulates steady-state amounts of CK1α. In line with a previous report (42), exogenous WNT and nicotinamide transform wild-type enteroid cultures, which exhibit increased proliferation and decreased differentiation reminiscent of organoids derived from tumors. CK1α abundance was significantly reduced in these hyperactivated enteroid cultures (Fig. 6, D and E, and fig. S6D). Unlike its effects on wild-type enteroids, SSTC3 potently suppressed the growth of these WNT-hyperactivated enteroids (Fig. 6E and fig. S6, E and F). To more directly address the role of CK1α expression on WNT activity and SSTC3 efficacy, we used different amounts of small interfering RNA (siRNA) to partially knock down CK1α abundance in 293T cells and examined the ability of SSTC3 to attenuate the increased WNT activity resulting from partial loss of CK1α. As expected, decreased CK1α abundance activated WNT signaling, and this increased activity was suppressed by the CK1α activator SSTC3 (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6. CK1α abundance dictates SSTC3 sensitivity.

(A) Representative immunoblot for CK1α abundance in intestinal crypts or tumors isolated from wt or Apcmin mice. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (B) Immunoblotting for CK1α abundance in organoids derived from wt mouse intestines or Apc mutant tumors. (C) Representative immunoblot for CK1α abundance in 293T cells transfected with control or APC siRNA. (D) Representative immunoblot for CK1α abundance in wt intestinal organoids maintained in regular niche factors alone (−) or supplemented with WNT3A and nicotinamide (Nico; 1 mM) to hyperactivate WNT signaling. (E) Morphology in intestinal organoids described in (D) treated with SSTC3 for 4 days. (F) TOPflash WNT reporter activity (left) in 293T cells after CK1α knockdown with SMARTpool siRNA (right) and treatment with vehicle or SSTC3 (100 nM for 24 hours). (G) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with tumors that had relatively high or low CK1α expression (GSE17538; n = 125 patients per group; *P ≤ 0.05). (H) Schematic demonstrating the selectivity of CK1α activators for WNT-dependent tumors.

The expression of CSNK1A1 (hereafter referred to as CK1α) is decreased in various human tumors relative to the tissue of origin, where it is thought to be tumor-suppressive. Taking advantage of a recent high-density transcriptome database of colorectal tumor samples linked to patient outcome, we noted that the expression of CK1α was significantly lower in colorectal adenomas and carcinomas relative to normal colonic tissue (fig. S6G). Segregation of this cohort of CRC patients into two groups, based on CK1α expression, revealed that survival was significantly decreased in patients whose tumors expressed relatively lower amounts of CK1α (Fig. 6G). These data are consistent both with CK1α expression being modulated during CRC progression to hyperactivate WNT signaling and with lower expression of CK1α being predictive of a poorer patient outcome.

DISCUSSION

We found that a novel small-molecule activator of CK1α, SSTC3, attenuates the growth of CRC cells via a mechanism dependent on CK1α and in a manner that attenuates WNT signaling. Taking advantage of the significantly improved bioavailability of SSTC3, we show for the first time the ability of CK1α activators to attenuate the growth of WNT-driven CRC in vivo. We further show that CK1α levels are decreased by constitutive WNT signaling and that this modulation of CK1α levels likely determines the sensitivity of a tissue to CK1α activators (Fig. 6H). This result is consistent with the role CK1α plays as a negative regulator of WNT signaling and with increased CK1α activity acting to down-regulate WNT activity (6, 41). Thus, normal intestinal tissue has high amounts of CK1α and is relatively insensitive to SSTC3, whereas colorectal tumors have hyperactivated WNT signaling that effectively lowers the amount of CK1α and are sensitive to CK1α activators (Fig. 6H). We further show that, in a cohort of CRC patients, decreased tumor expression of CK1α is associated with a worse prognosis, similar to what has been reported for a number of other human cancers (43–46). These findings validate CK1α as a novel therapeutic target in CRC and identify a cohort of patients most likely to benefit from treatment with a CK1α activator such as SSTC3.

CK1α plays important roles in a number of distinct signaling pathways. Thus, it remains plausible that a subset of SSTC3’s effects on CRC viability occur via a non-WNT–dependent mechanism. For example, CK1α has been implicated in the p53/MDM2 (47–49), FOXO1/autophagy (50–52), and sonic hedgehog–GLI (53–55) signaling pathways, all of which have also been implicated in aspects of CRC progression (56–59). Pyrvinium, the first-in-class CK1α activator, was reported to exert antitumor activity through suppression of GLI activity (60) or autophagy flux (61). Unlike its role in WNT signaling (62, 63), CK1α is able to function in multiple, and opposing, ways within these other signaling pathways (47, 48, 54, 55), complicating the ability to predict SSTC3 effects in different biological contexts. Because of this complexity, we cannot rule out that the simultaneous modulation of these other signaling pathways may affect the efficacy of SSTC3 in targeting WNT-dependent tumors, especially at high doses.

A number of WNT inhibitors are currently being evaluated in, or for, clinical trials (64). Given the importance of WNT signaling for stem cell function and homeostasis within numerous tissues (65), these trials are being scrutinized for both efficacy and on-target toxicities (64). On-target GI toxicity has been particularly problematic for both porcupine and TANKi (23, 26), with members of both classes of these drugs showing narrow concentration ranges between efficacy and GI toxicity in animal models (27). A number of biological agents that target WNT signaling components are also being evaluated in the clinic, where on-target bone toxicities emerged as a dose-limiting factor (64). CK1α activators inhibit the growth of WNT-driven CRC without obvious on-target toxicities. These findings are consistent with the lack of GI toxicity observed in mice chronically dosed with pyrvinium or reported in pinworm patients treated with the FDA-approved anthelmintic doses of pyrvinium (66). We have suggested a model in which CK1α activators preferentially target the lower levels of CK1α found in colorectal tumors (67). Thus, CK1α activators represent the first class of WNT inhibitors that preferentially target the hyperactivated signaling typically found in WNT-driven tumors while minimizing the on-target toxicities resulting from attenuation of WNT signaling in various regenerative tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of SSTC3 analogs

To synthesize 4-(N-methyl-N-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)sulfamoyl) benzoic acid, we mixed a solution of 4-(chlorosulfonyl)benzoic acid (0.5 g, 2.27 mmol) in methanol (10 ml) with N-methyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)aniline (1191 mg, 6.80 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 14 hours, concentrated, and then partitioned between ethyl acetate and 0.5 M HCl solution. The organics were separated and dried over magnesium sulfate. The resulting dark solid was partitioned between diethyl ether and 0.5 M sodium hydroxide solution. The aqueous layer was separated and acidified to pH 1 with concentrated HCl. The resulting suspension was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried over magnesium sulfate, and concentrated. The resulting solid was triturated with diethyl ether to provide the desired benzoic acid as a white solid. The yield was 385mg (47%). 1H–nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR): δ 8.11 (J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), and 3.21 (s, 3H).

To synthesize 4-(N-methyl-N-(4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl)sulfamoyl)-N-(4-pyridin-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)benzamide (SSTC3), we added diisopropylethylamine (0.12 ml, 0.69 mmol) and PyBOP (179 mg, 0.345 mmol) to a solution of 4-(N-methyl-N-(4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl) sulfamoyl)benzoic acid (100 mg, 0.28 mmol) in dimethylformamide (5 ml). The mixture was stirred for 10 min and was treated with 4-(pyridin-2-yl)thiazol-2-amine (41 mg, 0.23 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 hours, concentrated, and then partitioned between ethyl acetate and 5% lithium chloride solution. The organic layers were combined, dried over magnesium sulfate, and concentrated. The resulting dark oil was purified by column chromatography eluting with 50 to 100% ethyl acetate in hexanes. The resulting solid was triturated with diethyl ether to give the desired amide (SSTC3) as an off-white solid. The yield was 42 mg (35%). 1H-NMR [400MHz, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)–d6]: δ 8.60 (d, J = 4.0Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 8.02 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (dt; J = 7.5, 7.5, and 1.5 Hz; 1H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (d, J =8.5Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (dd, J = 7.0, 5.0Hz, 1H), and 3.25 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1H-NMR δ 129.3, 127.5, 127.1, 126.4, 126.1, 125.3, 122.9, 122.6, 120.1, and 112.5; high-resolution mass spectrometry (mass/charge ratio): [M]+ = calculated for C23H18F3N4O3S2, 519.0771; found, 519.0771; analysis (% calculated, %found for C23H17F3N4O3S2): C (53.28, 53.15),H(3.30, 3.43), and N (10.81, 10.81). The synthesis of SSTC111 and SSTC3with an amine linker (SSTC3 linker) was performed using the same procedures used to synthesize SSTC3. SSTC111 synthesis incorporates a modified thiazol-2-amine in the last step. SSTC3 linker was produced via functionalization of the sulfonamide group using Boc-aminoethyl bromide followed by Boc group removal with trifluoroacetic acid to give the corresponding trifluoroacetic acid salt of the amine. For the SSTC3-conjugated beads, 1.2 mg of SSTC3 linker compound (solubilized in 30% DMSO) was covalently coupled to 2 ml of AminoLink Coupling Resin (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell lines and assays

CRC cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained as recommended. An isogenic HCT116 cell line, in which the CTNNB1 (β-catenin) mutant allele that drives its tumorigenic properties was deleted, was a gift of B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University). The distinct shRNAs against CK1α used here were previously described (29). A luciferase-based TOPflash reporter system was used to assess WNT signaling activity and normalized to total protein. qRT-PCR using specific TaqMan probes (Invitrogen) was performed on total RNA. Expression of GAPDH (encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) or 18S ribosomal RNA was used as reference genes for cells or tissues, respectively. Radioactive kinase reaction was performed as previously described (16). Briefly, a [γ32P]-ATP kinase reaction buffer containing recombinant CK1α (25 nM; Invitrogen) and vehicle (DMSO) or SSTC3 (100 nM) was preincubated at 30°C for 5 min. The kinase reaction was initiated with the addition of recombinant β-catenin (final, 100 nM) and briefly vortexed. Samples were withdrawn at various times, and reactions were terminated with addition to protein sample buffer. The primary antibodies used for immunoblotting are CK1α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phosphorylated Ser45 β-catenin (Cell Signaling Technology), β-catenin (Cell Signaling Technology), GAPDH (Ambion), HSP90 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and APC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunohistochemistry was performed at the University of Miami Medical School Pathology Research core using the indicated antibodies. APC and CK1α siRNA SMARTpool and control siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon.

Surface plasmon resonance sensorgram analysis

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments were performed on a Biacore T200 instrument (GE Healthcare) at 25°C. SSTC3 linker molecule was covalently immobilized to the surface of a CM5 sensor chip by standard amine coupling. A reference flow cell was prepared by activation and deactivation of the surface. Different concentrations of CK1α (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 50 mM tris buffer (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 5% DMSO were injected for 60 s at 30 µl/ml. Regeneration of the surface was achieved with 30-s injections of Gly-HCl (pH 2.0) and 50% DMSO. Data were fitted to a 1:1 binding model using Biacore T200 evaluation software (GE Healthcare).

Three-dimensional organoid culture

Wild-type organoids (enteroids) were established from the isolated intestinal crypts of BALB/c mice as previously described (40). Briefly, jejunum from ~8-week-old mice was removed and gavage-washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by incubation with cold PBS containing 1.5 mM dithiothreitol and 30 mM EDTA for 20 min. The intestinal tissue was then incubated with warm PBS containing 15 mM EDTA for 6 min, followed by extensive shaking to release the intestinal crypts. After centrifugation, the resulting crypt pellet was washed with 30× volume of organoid basal medium [Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMAX, 10 mM Hepes, penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml), and 1× N2 and 1× B27 supplements]. The purified crypts were filtered through a 100-µm cell strainer and embedded in growth factor–reduced Matrigel (Corning). The resultant organoids were maintained in basal medium supplemented with niche factors [epidermal growth factor (50 ng/ml), R-spondin1 (250 ng/ml), Noggin (100 ng/ml), and 1 µM Jagged-1]. Organoids derived from Apcmin (35), Apc−/− mouse (36) adenomas, or clinical CRC-resected tissues were established using a similar protocol, with an additional collagenase and dispase digestion step after the EDTA-chelation step (68). Hyperactivation of WNT signaling in wild-type organoids was achieved by supplementing regular niche factor medium with 25% L-WRN conditioned medium (69) and 1mM nicotinamide for a week (42). Human tumor samples were obtained via an institutional review board–approved protocol.

X. laevis injections

Xenopus embryos were in vitro fertilized, dejellied, cultured, and injected as previously described (70). Capped Xwnt8 was generated using mMESSAGE mMACHINE (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All the work performed on Xenopus embryos was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Vanderbilt University and was in accordance with their policies and guidelines.

Mouse experiments

All studies were carried out in accordance with recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and with the policies of the University of Miami IACUC. Age-matched Apcmin mice (C57BL/6J-ApcMin/J) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Cancer cell line xenografts were established using CD-1 nu/nu mice (Charles River Laboratories) and exposed to the indicated small molecules by intraperitoneal injection. Quantitation of intestinal tumor in Apcmin mice was performed as described (71). Briefly, whole intestine from vehicle- or SSTC3-treated Apcmin mice was isolated, flushed with PBS, opened, and mounted on a filter paper. Intestinal tissues were then fixed with formalin for 10 min and subject to methylene blue staining to visualize the polyps. For immunoblotting analysis of CK1α in Apc mutant tumors, small intestines from Apcmin mice were mounted on a filter paper via a similar procedure and isolated using a surgical scalpel. CRC PDXs were established using NOD scid gamma mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Resected CRCs were obtained from consented patients undergoing surgery at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center of the University of Miami. Cancer-driving mutations in primary CRC samples were screened by TruSeq Amplicon technology (Illumina) using a designated cancer panel. To assess GI toxicity in vivo, the intestinal tract was removed from euthanized mice, opened and flushed with PBS, and subsequently fixed using 10% neutral buffered formalin. The fixed intestinal tissue was embedded in paraffin and cut into 4-µm-thick sections, and H&E staining was assessed via light microscopy. Tumor sections were similarly harvested and stained. We evaluated the pharmacokinetic characteristics of SSTC3 by administering a single dose (25 mg/kg) to three mice via intraperitoneal injection. Blood samples were collected at about 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 hours after dose. Plasma samples were assayed for SSTC3 using a validated bioanalytical LC-MS method performed by a contract research organization (Covance-Madison), and the results were used to determine various pharmacokinetic parameters, including Cmax and AUC values. The Cmax and AUC0–24 values were 3910 ng/ml (7.5 µM) and 29,300 ng·hours/ml, respectively, with exposures above 250 nM in the plasma for >24 hours.

Bioinformatics analysis of CK1α expression

Gene expression data were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE17538) and normalized using Robust Multi-array Average in the Bioconductor package Affy. Box and whisker plots were used to show log2-transformed CK1α gene expression (probe 226920_at), where the box represents the first and third quartiles, the thick band is the median, and the bars extend to ±1.58 the interquartile range divided by the square root of the sample number.

Statistical analyses

Unless otherwise indicated, all error bars shown represent the SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was determined using Student’s t test, Fisher’s exact test, or a log-rank Mantel-Cox test to analyze the Kaplan-Meier survival curves. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant and marked with an asterisk.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. SSTC3 inhibits WNT signaling via CK1α.

Fig. S2. SSTC3 attenuates the viability of cells dependent on WNT activity.

Fig. S3. A structural analog of SSTC3, SSTC111, does not inhibit WNT biomarkers in CRC cells.

Fig. S4. SSTC3 treatment decreases tumor cell density in CRC xenografts.

Fig. S5. SSTC3 has limited on-target GI toxicity in mice.

Fig. S6. Decreased abundance of CK1a sensitizes cells to SSTC3.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Robbins, Capobianco, and Lee laboratories, as well as F. de Sauvage (Genentech) and D. Hernandez (University of Miami) for providing helpful insights during discussions regarding this work. We are grateful to J. Shay (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) for providing colonic Apc mutant mice and B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University) for providing isogenic HCT116 cells. Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R37DK34128 (to M.H.C.), R01GM081635 (to E.L.), R01GM103926 (to E.L.), R35GM122516-01 (to E.L.), 1K99DK103126-01 (to C.T.), R01CA083736-12A1 (to A.J.C.), R01CA125044-02 (to A.J.C.), and R01CA082628 (to D.J.R.) and funds from the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Author contributions: B.L., D.O., and D.J.R. conceived and designed the study. B.L., D.O., L.R.N., C.S., L.A., J.L., X.C., K.C.K., J.Z., C.T., Z.W., K.J., D.M.N., L.R.S., and F.M. acquired the data and provided experimental support. B.L., D.O., L.R.N., L.A., X.C., J.Z., J.R.-B., M.T.A., A.J.C., and D.J.R. analyzed and interpreted the data. B.L. and D.J.R. drafted the manuscript. T.D., M.L.G., D.L.F., M.T.A., M.H.C., E.L., and D.J.R. critically revised the manuscript.

Competing interests: D.J.R., A.J.C., and E.L. are founders of StemSynergy Therapeutics Inc., a company commercializing small-molecule cell signaling inhibitors. D.O., K.C.K., M.L.G., and T.D. are employees of StemSynergy Therapeutics.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon ER. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:479–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dow LE, O’Rourke KP, Simon J, Tschaharganeh DF, van Es JH, Clevers H, Lowe SW. Apc restoration promotes cellular differentiation and reestablishes crypt homeostasis in colorectal cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1539–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao H, Xu E, Liu H, Wan L, Lai M. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer metastasis: A system review. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2015;211:557–569. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amit S, Hatzubai A, Birman Y, Andersen JS, Ben-Shushan E, Mann M, Ben-Neriah Y, Alkalay I. Axin-mediated CKI phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser 45: A molecular switch for the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1066–1076. doi: 10.1101/gad.230302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang S-MA, Mishina YM, Liu S, Cheung A, Stegmeier F, Michaud GA, Charlat O, Wiellette E, Zhang Y, Wiessner S, Hild M, Shi X, Wilson CJ, Mickanin C, Myer V, Fazal A, Tomlinson R, Serluca F, Shao W, Cheng H, Shultz M, Rau C, Schirle M, Schlegl J, Ghidelli S, Fawell S, Lu C, Curtis D, Kirschner MW, Lengauer C, Finan PM, Tallarico JA, Bouwmeester T, Porter JA, Bauer A, Cong F. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/β-catenin signaling: Components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Port F, Basler K. Wnt trafficking: New insights into Wnt maturation, secretion and spreading. Traffic. 2010;11:1265–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Heuvel M, Harryman-Samos C, Klingensmith J, Perrimon N, Nusse R. Mutations in the segment polarity genes wingless and porcupine impair secretion of the wingless protein. EMBO J. 1993;12:5293–5302. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadowaki T, Wilder E, Klingensmith J, Zachary K, Perrimon N. The segment polarity gene porcupine encodes a putative multitransmembrane protein involved in Wingless processing. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3116–3128. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janda CY, Waghray D, Levin AM, Thomas C, Garcia KC. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science. 2012;337:59–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1222879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto H, Kishida S, Kishida M, Ikeda S, Takada S, Kikuchi A. Phosphorylation of axin, a Wnt signal negative regulator, by glycogen synthase kinase-3β regulates its stability. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10681–10684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolwinski NS, Wehrli M, Rives A, Erdeniz N, DiNardo S, Wieschaus E. Wg/Wnt signal can be transmitted through arrow/LRP5,6 and Axin independently of Zw3/Gsk3β activity. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:407–418. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kofron M, Birsoy B, Houston D, Tao Q, Wylie C, Heasman J. Wnt11/β-catenin signaling in both oocytes and early embryos acts through LRP6-mediated regulation of axin. Development. 2007;134:503–513. doi: 10.1242/dev.02739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cselenyi CS, Jernigan KK, Tahinci E, Thorne CA, Lee LA, Lee E. LRP6 transduces a canonical Wnt signal independently of Axin degradation by inhibiting GSK3’s phosphorylation of β-catenin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:8032–8037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803025105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson B, Townsley F, Rosin-Arbesfeld R, Musisi H, Bienz M. A new nuclear component of the Wnt signalling pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:367–373. doi: 10.1038/ncb786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker DS, Jemison J, Cadigan KM. Pygopus, a nuclear PHD-finger protein required for Wingless signaling in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:2565–2576. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramps T, Peter O, Brunner E, Nellen D, Froesch B, Chatterjee S, Murone M, Zullig S, Basler K. Wnt/wingless signaling requires BCL9/legless-mediated recruitment of pygopus to the nuclear β-catenin-TCF complex. Cell. 2002;109:47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00679-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan C-W, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, Roth MG, Amatruda JF, Chen C, Lum L. Small molecule–mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito-Diaz K, Chen TW, Wang X, Thorne CA, Wallace HA, Page-McCaw A, Lee E. The way Wnt works: Components and mechanism. Growth Factors. 2013;31:1–31. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2012.752737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau T, Chan E, Callow M, Waaler J, Boggs J, Blake RA, Magnuson S, Sambrone A, Schutten M, Firestein R, Machon O, Korinek V, Choo E, Diaz D, Merchant M, Polakis P, Holsworth DD, Krauss S, Costa M. A novel tankyrase small-molecule inhibitor suppresses APC mutation–driven colorectal tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3132–3144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinto D, Gregorieff A, Begthel H, Clevers H. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1709–1713. doi: 10.1101/gad.267103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fevr T, Robine S, Louvard D, Huelsken J. Wnt/β-catenin is essential for intestinal homeostasis and maintenance of intestinal stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:7551–7559. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Pan S, Hsieh MH, Ng N, Sun F, Wang T, Kasibhatla S, Schuller AG, Li AG, Cheng D, Li J, Tompkins C, Pferdekamper A, Steffy A, Cheng J, Kowal C, Phung V, Guo G, Wang Y, Graham MP, Flynn S, Brenner JC, Li C, Villarroel MC, Schultz PG, Wu X, McNamara P, Sellers WR, Petruzzelli L, Boral AL, Seidel HM, McLaughlin ME, Che J, Carey TE, Vanasse G, Harris JL. Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:20224–20229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong Y, Katavolos P, Nguyen T, Lau T, Boggs J, Sambrone A, Kan D, Merchant M, Harstad E, Diaz D, Costa M, Schutten M. Tankyrase inhibition causes reversible intestinal toxicity in mice with a therapeutic index < 1. Toxicol. Pathol. 2016;44:267–278. doi: 10.1177/0192623315621192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorne CA, Hanson AJ, Schneider J, Tahinci E, Orton D, Cselenyi CS, Jernigan KK, Meyers KC, Hang BI, Waterson AG, Kim K, Melancon B, Ghidu VP, Sulikowski GA, LaFleur B, Salic A, Lee LA, Miller DM, III, Lee E. Small-molecule inhibition of Wnt signaling through activation of casein kinase 1α. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:829–836. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, Flaveny CA, Giambelli C, Fei DL, Han L, Hang BI, Bai F, Pei X-H, Nose V, Burlingame O, Capobianco AJ, Orton D, Lee E, Robbins DJ. Repurposing the FDA-approved pinworm drug pyrvinium as a novel chemotherapeutic agent for intestinal polyposis. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e101969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lake RS, Kropko ML, de la Iglesia FA. Absence of in vitro genotoxicity of pyrvinium pamoate in sister-chromatid exchange, chromosome aberration, and HGPRT-locus mutation bioassays. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 1982;10:255–266. doi: 10.1080/15287398209530248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith TC, Kinkel AW, Gryczko CM, Goulet JR. Absorption of pyrvinium pamoate. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1976;19:802–806. doi: 10.1002/cpt1976196802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astudillo L, Da Silva TG, Wang Z, Han X, Jin K, VanWye J, Zhu X, Weaver K, Oashi T, Lopes PEM, Orton D, Neitzel LR, Lee E, Landgraf R, Robbins DJ, MacKerell AD, Jr, Capobianco AJ. The small molecule IMR-1 inhibits the Notch transcriptional activation complex to suppress tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3593–3603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larabell CA, Torres M, Rowning BA, Yost C, Miller JR, Wu M, Kimelman D, Moon RT. Establishment of the dorso-ventral axis in Xenopus embryos is presaged by early asymmetries in β-catenin that are modulated by the Wnt signaling pathway. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:1123–1136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, Gould KA, Dove WF. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luongo C, Moser AR, Gledhill S, Dove WF. Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5947–5952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hinoi T, Akyol A, Theisen BK, Ferguson DO, Greenson JK, Williams BO, Cho KR, Fearon ER. Mouse model of colonic adenoma-carcinoma progression based on somatic Apc inactivation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9721–9730. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, Vries RGJ, van Es JH, van den Brink S, van Houdt WJ, Pronk A, van Gorp J, Siersema PD, Clevers H. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247:322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shoemaker AR, Gould KA, Luongo C, Moser AR, Dove WF. Studies of neoplasia in the Min mouse. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1332:F25–F48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(96)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elyada E, Pribluda A, Goldstein RE, Morgenstern Y, Brachya G, Cojocaru G, Snir-Alkalay I, Burstain I, Haffner-Krausz R, Jung S, Wiener Z, Alitalo K, Oren M, Pikarsky E, Ben-Neriah Y. CKIα ablation highlights a critical role for p53 in invasiveness control. Nature. 2011;470:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature09673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andersson-Rolf A, Fink J, Mustata RC, Koo B-K. A video protocol of retroviral infection in primary intestinal organoid culture. J. Visualized Exp. 2014:e51765. doi: 10.3791/51765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sinnberg T, Menzel M, Kaesler S, Biedermann T, Sauer B, Nahnsen S, Schwarz M, Garbe C, Schittek B. Suppression of casein kinase 1α in melanoma cells induces a switch in β-catenin signaling to promote metastasis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6999–7009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schittek B, Sinnberg T. Biological functions of casein kinase 1 isoforms and putative roles in tumorigenesis. Mol. Cancer. 2014;13:231. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang K, Ma L, Zhang L, Wang J. Clinicopathological significance and prognostic value of CK1α expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2016;9:1989–1995. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin T-C, Su C-Y, Wu P-Y, Lai T-C, Pan W-A, Jan Y-H, Chang Y-C, Yeh C-T, Chen C-L, Ger L-P, Chang H-T, Yang C-J, Huang M-S, Liu Y-P, Lin Y-F, Shyy JY-J, Tsai M-D, Hsiao M. The nucleolar protein NIFK promotes cancer progression via CK1α/β-catenin in metastasis and Ki-67-dependent cell proliferation. eLife. 2016;5:e11288. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venerando A, Marin O, Cozza G, Bustos VH, Sarno S, Pinna LA. Isoform specific phosphorylation of p53 by protein kinase CK1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:1105–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0236-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huart A-S, MacLaine NJ, Meek DW, Hupp TR. CK1α plays a central role in mediating MDM2 control of p53 and E2F-1 protein stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:32384–32394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu S, Chen L, Becker A, Schonbrunn E, Chen J. Casein kinase 1α regulates an MDMX intramolecular interaction to stimulate p53 binding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32:4821–4832. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00851-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szyniarowski P, Corcelle-Termeau E, Farkas T, Høyer-Hansen M, Nylandsted J, Kallunki T, Jäättelä M. A comprehensive siRNA screen for kinases that suppress macroautophagy in optimal growth conditions. Autophagy. 2011;7:892–903. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.8.15770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hale CM, Cheng Q, Ortuno D, Huang M, Nojima D, Kassner PD, Wang S, Ollmann MM, Carlisle HJ. Identification of modulators of autophagic flux in an image-based high content siRNA screen. Autophagy. 2016;12:713–726. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1147669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheong JK, Zhang F, Chua PJ, Bay BH, Thorburn A, Virshup DM. Casein kinase 1α-dependent feedback loop controls autophagy in RAS-driven cancers. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:1401–1418. doi: 10.1172/JCI78018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Q, Shi Q, Chen Y, Yue T, Li S, Wang B, Jiang J. Multiple Ser/Thr-rich degrons mediate the degradation of Ci/Gli by the Cul3-HIB/SPOP E3 ubiquitin ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:21191–21196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912008106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jia J, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Tong C, Wang B, Hou F, Amanai K, Jiang J. Phosphorylation by double-time/CKIε and CKIα targets cubitus interruptus for Slimb/β-TRCP-mediated proteolytic processing. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:819–830. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Y, Sasai N, Ma G, Yue T, Jia J, Briscoe J, Jiang J. Sonic Hedgehog dependent phosphorylation by CK1α and GRK2 is required for ciliary accumulation and activation of smoothened. PLOS Biol. 2011;9:e1001083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naccarati A, Polakova V, Pardini B, Vodickova L, Hemminki K, Kumar R, Vodicka P. Mutations and polymorphisms in TP53 gene—An overview on the role in colorectal cancer. Mutagenesis. 2012;27:211–218. doi: 10.1093/mutage/ger067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Varnat F, Duquet A, Malerba M, Zbinden M, Mas C, Gervaz P, Ruiz i Altaba A. Human colon cancer epithelial cells harbour active HEDGEHOG-GLI signalling that is essential for tumour growth, recurrence, metastasis and stem cell survival and expansion. EMBO Mol. Med. 2009;1:338–351. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sato K, Tsuchihara K, Fujii S, Sugiyama M, Goya T, Atomi Y, Ueno T, Ochiai A, Esumi H. Autophagy is activated in colorectal cancer cells and contributes to the tolerance to nutrient deprivation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9677–9684. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akiyoshi T, Nakamura M, Koga K, Nakashima H, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Tanaka M, Katano M. Gli1, downregulated in colorectal cancers, inhibits proliferation of colon cancer cells involving Wnt signalling activation. Gut. 2006;55:991–999. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.080333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li B, Fei DL, Flaveny CA, Dahmane N, Baubet V, Wang Z, Bai F, Pei X-H, Rodriguez-Blanco J, Hang B, Orton D, Han L, Wang B, Capobianco AJ, Lee E, Robbins DJ. Pyrvinium attenuates Hedgehog signaling downstream of smoothened. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4811–4821. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deng L, Lei Y, Liu R, Li J, Yuan K, Li Y, Chen Y, Liu Y, Lu Y, Edwards CK, III, Huang C, Wei Y. Pyrvinium targets autophagy addiction to promote cancer cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e614. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hernández AR, Klein AM, Kirschner MW. Kinetic responses of β-catenin specify the sites of Wnt control. Science. 2012;338:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1228734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sinnberg T, Wang J, Sauer B, Schittek B. Casein kinase 1α has a non-redundant and dominant role within the CK1 family in melanoma progression. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:594. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2643-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kahn M. Can we safely target the WNT pathway? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:513–532. doi: 10.1038/nrd4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nusse R. Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Cell Res. 2008;18:523–527. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beck JW, Saavedra D, Antell GJ, Tejeiro B. The treatment of pinworm infections in humans (enterobiasis) with pyrvinium chloride and pyrvinium pamoate. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1959;8:349–352. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1959.8.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anastas JN, Moon RT. WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:11–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xue X, Shah YM. In vitro organoid culture of primary mouse colon tumors. J. Visualized Exp. 2013:e50210. doi: 10.3791/50210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyoshi H, Stappenbeck TS. In vitro expansion and genetic modification of gastrointestinal stem cells in spheroid culture. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2471–2482. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peng HB. Xenopus laevis: Practical uses in cell and molecular biology. Solutions and protocols. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:657–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoneda M, Molinolo AA, Ward JM, Kimura S, Goodlad RA. A simple device to rapidly prepare whole mounts of the mouse intestine. J. Visualized Exp. 2015:e53042. doi: 10.3791/53042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. SSTC3 inhibits WNT signaling via CK1α.

Fig. S2. SSTC3 attenuates the viability of cells dependent on WNT activity.

Fig. S3. A structural analog of SSTC3, SSTC111, does not inhibit WNT biomarkers in CRC cells.

Fig. S4. SSTC3 treatment decreases tumor cell density in CRC xenografts.

Fig. S5. SSTC3 has limited on-target GI toxicity in mice.

Fig. S6. Decreased abundance of CK1a sensitizes cells to SSTC3.