Abstract

We examined the hypothesis that plasma biomarkers and concomitant clinical findings after initial glucocorticoid therapy can accurately predict failure of graft-versus-host-disease treatment and mortality. We analyzed plasma samples and clinical data in 165 patients after 14 days of glucocorticoid therapy and used logistic regression and areas under receiver-operating characteristic curves (AUC) to evaluate associations with treatment failure and non-relapse mortality (NRM). Initial treatment of GVHD was unsuccessful in 49 patients (30%). For predicting GVHD treatment failure, the best clinical combination (total serum bilirubin and skin GVHD stage, AUC 0.70) was competitive with the best biomarker combination (TIM3 and ST2, AUC 0.73). The combination of clinical features and biomarker results offered only a slight improvement (AUC 0.75). For predicting NRM at 1 year, the best clinical predictor (total serum bilirubin, AUC 0.81) was competitive with the best biomarker combination (TIM3 and sTNFR1, AUC 0.85). The combination offered no improvement (AUC 0.85). Infection was the proximate cause of death in virtually all patients.

We conclude that after 14 days of glucocorticoid therapy, clinical findings (serum bilirubin, skin GVHD) and plasma biomarkers (TIM3, ST2, sTNFR1) can predict failure of GVHD treatment and non-relapse mortality. These biomarkers reflect counter-regulatory mechanisms and provide insight into the pathophysiology of GVHD reactions following glucocorticoid treatment. The best predictive models, however, exhibit inadequate positive predictive values for identifying high-risk GVHD cohorts for investigational trials, as only a minority of patients with high-risk GVHD would be identified, and most patients would be falsely predicted to have adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Marrow transplantation, hematopoietic cell transplantation, allogeneic, graft-vs.-host disease, biomarker, treatment failure, mortality, outcomes, cause of death, positive predictive value

Introduction

The frequency of acute GVHD following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is in the 50 to 70% range, with gastrointestinal symptoms the most common presentation.1,2 The overall severity of GVHD has recently shifted toward less severe organ involvement and improved survival.1,3 Newer methods of GVHD prophylaxis such as post-transplant cyclophosphamide, depletion of naïve T-cells from the graft and better HLA matching of unrelated donors and recipients have improved outcomes.4–10 Nevertheless, GVHD remains a formidable problem because of incomplete treatment responses, need for prolonged immune suppression, treatment-related toxicity, and fatal infections.

The backbone of GVHD therapy is prednisone or methylprednisolone.2,11 Ideally, GVHD management could be improved by adopting a personalized treatment strategy where patients predicted to have treatment-responsive GVHD could be effectively treated with lower doses of prednisone or shorter-duration systemic therapy in conjunction with oral topical glucocorticoid.12–14 This approach to treatment is inappropriate for patients who have findings at disease onset that are associated with more severe GVHD and a greater risk of non-relapse mortality.2,12 Several studies have tested the hypothesis that plasma biomarkers measured at GVHD onset or at a set time after transplant can predict whether GVHD is likely to respond to initial treatment or not.3,15–19 We recently reported a study of plasma biomarkers measured before the clinical onset of acute GVHD.20 A panel of IL6, TIM3, and sTNFR1 was associated with subsequent peak grade 3–4 GVHD and a panel of ST2 and sTNFR1 was associated with non-relapse mortality at one year. The positive predictive value of all biomarker panels published to date, including ours, is suboptimal. When the probability of poor outcomes is low, the sensitivity and specificity of predictive tests must be very high in order to achieve clinically useful positive and negative predictive values at any biomarker cut point. This degree of biomarker predictive accuracy has not yet been met with regard to outcomes in patients with acute GVHD.

In the current study, we examined the hypothesis that biomarkers in blood samples drawn 2 weeks after the start of glucocorticoid therapy for GVHD, with or without concomitant clinical findings, can accurately predict failure of GVHD treatment and non-relapse mortality. The overall aim was to identify patients at high risk of treatment failure and non-relapse mortality as accurately as possible, so that early interventions could be tested for efficacy in preventing these outcomes.

Methods

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation

Pre-transplant conditioning regimens generally contained high-dose cyclophosphamide with busulfan or 12–13.2 Gy total body irradiation (TBI) or fludarabine with 2–4 Gy TBI. Recipients were usually given a calcineurin inhibitor plus methotrexate or mycophenolate to prevent GVHD. Prophylactic medications included antimicrobial drugs for infection and ursodiol for cholestasis.

Study design

Patients who consented to research blood collection and analysis of clinical data under protocols approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Review Board and who developed acute GVHD comprised the study cohort. Blood samples for biomarker analysis were collected prospectively under the auspices of two protocols, one an observational study, the other a GVHD prophylaxis protocol (NCT00489203). Clinical and laboratory manifestations of GVHD and outcomes were reviewed in retrospect. After 14±7 days of glucocorticoid treatment for GVHD, we collected a blood sample and concomitant clinical data related to GVHD, including gut GVHD stage (diarrhea, upper gut symptoms); skin GVHD stage; prednisone dose; laboratory tests (serum albumin, total serum bilirubin, calculated glomerular filtration rate); and a subjective global assessment of the course of GVHD from baseline (improved, worsened, or unchanged, based on notes from the attending physician and patient care team). Demographic factors previously noted to have an impact on GVHD treatment outcomes (time from transplant to start of glucocorticoid treatment, HLA mismatch, and GVHD prophylaxis) were also analyzed as potential predictors of outcome.21 In the blood samples, we measured the levels of eight analytes, six that had been shown to be most predictive of the severity of GVHD and non-relapse mortality in a previous study of blood samples drawn before the clinical onset of GVHD20, and two recently described analytes associated with GVHD, angiopoietin-2 (ANG-2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).18,22

Outcomes of interest were non-relapse mortality (NRM) within one year after the blood sample was drawn and failure of initial glucocorticoid treatment for GVHD. NRM was defined as a death during the year following GVHD treatment day 14±7 without prior recurrent or progressive hematologic malignancy. Failure of initial treatment of GVHD was defined during a 56-day observation period after the start of therapy as either initiation of secondary systemic therapy for GVHD, death, the onset of chronic GVHD by National Institutes of Health criteria, or an average prednisone dose ≥0.5 mg/kg/day during days 55 and 56 after initiation of treatment. This threshold prednisone dose for defining GVHD treatment failure was determined by comparing the average prednisone dose during treatment days 29–56, 50–56, and 55–56 as related to NRM within 1 year after treatment day 14 (Supplement Table S1, Supplement Figure S1). The highest area under a receiver-operating characteristic curve was found with average prednisone dose on treatment days 55–56.

Collection, processing and analysis of blood samples

Blood samples were collected as previously described.20,23 The Luminex microbead method (Luminex, Austin TX) was used for measurement of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), interleukin-6 (IL6), soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (sTNFR1), T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM3), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), and interleukin 1 receptor family encoded by the IL1RL1 gene (ST2).20,23 For the analyte angiopoietin 2 (ANG-2), capture (MAB098) and detection (BAM0981) antibodies were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis MN); the lower limit of detection was 30 pg/mL. For vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), capture (MAB293) and detection (BAF293) antibodies were obtained from R&D Systems; the lower limit of detectin was 8.0 pg/mL.

Statistical methods

All biomarker values were log-transformed before analysis. Values at the lower limit of detection were assigned that value. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association of plasma biomarkers or clinical factors with outcome, including the calculation of area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. We have chosen binary endpoints because these are directly amenable to calculation of predictive parameters such as sensitivity and positive predictive value, which are critical for evaluating potential clinical applications. The best models using biomarkers alone or using clinical and laboratory factors alone were determined by forward selection at the 0.05 level of significance. Backward selection yielded the same model in each case. The plasma biomarker and clinical factors from the best models were then combined in a single model.

Results

Demographics of patients

The study cohort of 165 patients (Table 1) included 81 who had provided samples before the onset of GVHD in a prior study20 and 84 who provided samples solely for this study. Blood samples were drawn at a median of 14 days [Interquartile Range (IQR) 13–17 days] after starting glucocorticoid therapy, which was at a median of 44 days after transplantation (IQR 35–58).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 165 patients treated for acute GVHD.

| Median age in years (range) | 45 (8–71) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Diagnosis n (%) | |

|

| |

| Acute leukemia | 81 (49) |

|

| |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 37 (22) |

|

| |

| Lymphoma | 23 (14) |

|

| |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 15 (9) |

|

| |

| Other diagnosis | 9 (6) |

|

| |

| Donor type n (%) | |

|

| |

| Related | 59 (36) |

|

| |

| Unrelated | 106 (64) |

|

| |

| HLA match n (%) | |

|

| |

| Matched | 132 (80) |

|

| |

| Mismatched | 33 (20) |

|

| |

| Graft type n (%) | |

|

| |

| Marrow | 30 (18) |

|

| |

| Peripheral blood | 135 (82) |

|

| |

| Sex match n (%) | |

|

| |

| Female donor to male recipient | 46 (28) |

|

| |

| Other | 119 (72) |

|

| |

| Conditioning regimens n (%) | |

|

| |

| Myeloablative* | 134 (81) |

|

| |

| Reduced intensity non-myeloablative | 31 (19) |

|

| |

| CMV serostatus before transplant (donor / recipient) n (%) | |

|

| |

| +/+ | 47 (29) |

| −/+ | 37 (22) |

| +/− | 25 (15) |

| −/− | 56 (34) |

|

| |

| GVHD prophylaxis n (%) | |

|

| |

| Calcineurin inhibitor + methotrexate | 118 (72) |

|

| |

| Calcineurin inhibitor + methotrexate + mycophenolate mofetil | 4 (2) |

|

| |

| Calcineurin inhibitor + mycophenolate mofetil | 35 (21) |

|

| |

| Other regimens | 8 (5) |

Five patients received ATG as part of their conditioning therapy.

Stages and grade of acute GVHD at baseline and at the time of the 14-day evaluation after initiation of prednisone therapy are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Numbers of patients in each stage and grade of acute GVHD, at the start of prednisone treatment and on the date of the plasma sample analyzed for biomarkers.

| At the start of prednisone treatment |

At the time of the ‘Day 14’ biomarker sample |

|

|---|---|---|

| Skin stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 103 (62) | 134 (81) |

| 1 | 4 (2) | 11 (7) |

| 2 | 17 (10) | 9 (5) |

| 3 | 40 (24) | 10 (6) |

| 4 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Gut stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 15 (9) | 157 (95) |

| 1 | 133 (81) | 6 (4) |

| 2 | 10 (6) | -- |

| 3 | 6 (4) | 1 (1) |

| 4 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Liver stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 146 (88) | 153 (93) |

| 1 | 8 (5) | 4 (2) |

| 2 | 6 (4) | 5 (3) |

| 3 | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| 4 | 3 (2) | -- |

| Overall grade, n (%) | ||

| 0 | -- | 122 (74) |

| 1 | 2 (1) | 17 (10) |

| 2 | 136 (82) | 18 (11) |

| 3 | 23 (14) | 7 (4) |

| 4 | 4 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Overall response, n (%) | ||

| Improved | -- | 153 (93) |

| Stable | -- | 5 (3) |

| Worse | -- | 7 (4) |

| Prednisone dose, mg/kg/day - median (range) | 1.0 (0.3 – 2.7) | 0.9 (0.0 – 2.9) |

Failure of initial treatment of acute GVHD

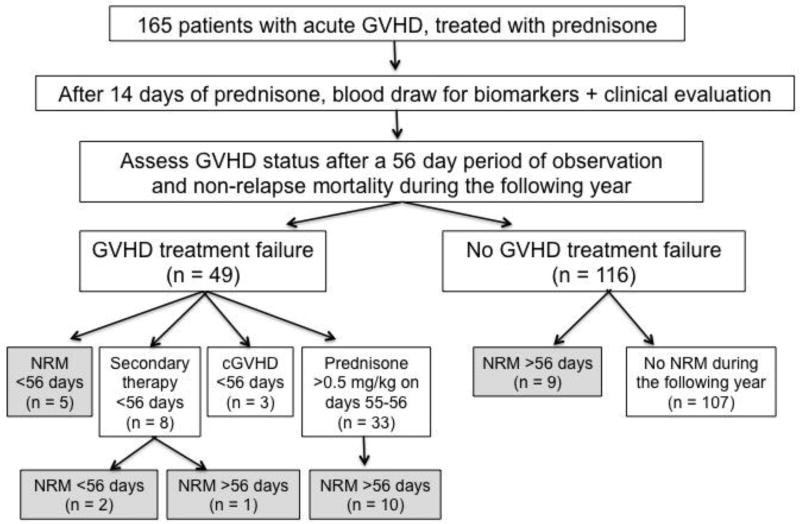

During the 56 day observation period from the start of prednisone therapy, 49 patients (30%) had GVHD that failed to respond to initial glucocorticoid treatment, including 5 who died without relapse, 8 who received secondary GVHD therapy, 3 who developed chronic GVHD, and 33 for whom treatment failure was defined by an average prednisone dose ≥0.5 mg/kg on treatment days 55–56 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of study design and outcomes following initial GVHD treatment. Shaded boxes denote patients groups who died before relapse within 1 year after the treatment day 14 biomarker and clinical factor measurements. Five patients died at a median of 29 days (range, 14 to 47 days) from the start of prednisone therapy without receiving secondary therapy and without completing the first 56 days of prednisone therapy. The three deceased patients who received secondary GVHD therapy died at 38, 38, and 79 days from the start of prednisone therapy. The ten deceased patients who had required ≥0.5 mg/kg prednisone on observation days 55–56 died at a median of 101 days (range, 69 to 196 days) from the start of prednisone therapy. Nine deceased patients who had not met criteria for GVHD treatment failure during the 56-day observation period died without relapse at a median of 193 days (range, 113 to 336 days) from the start of prednisone therapy.

Non-relapse mortality within 1 year of day 14 of GVHD treatment

During the year after day 14 of GVHD treatment, 27 patients died without prior recurrent or progressive malignancy (Figure 1, shaded boxes). Eighteen deaths occurred among 49 patients (37%) who met criteria for GVHD treatment failure and 9 deaths occurred among 116 patients (8%) who had not met criteria for treatment failure during 56 days of observation.

Plasma biomarker concentrations after 14 days of prednisone treatment of GVHD

Table 3 displays median values for eight analytes in plasma samples obtained at 14±7 days after starting prednisone therapy for three patient cohorts: (i) 107 patients who experienced neither GVHD treatment failure during 56 days of observation nor NRM within 1 year; (ii) 49 patients who experienced GVHD treatment failure within a 56-day observation period after starting prednisone therapy; and (iii) 27 patients who had NRM within 1 year.

Table 3.

Plasma biomarker levels by outcome group, expressed as the median value and interquartile range (IQR, Q1 – Q3) in pg/mL.

| No GVHD treatment failure or NRM by 1 year from day 14 of treatment (n=107) |

GVHD treatment failure within 56 days from start of prednisone (n=49) |

NRM within 1 year from day 14 of treatment (n=27) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

|

| |||

| ANG-2 | 215 (82–457) | 344 (86–937) | 497 (194–1222) |

|

| |||

| HGF | 180 (117–284) | 261 (156–423) | 297 (152–567) |

|

| |||

| IL6 | 0.92 (0.57–1.46) | 0.92 (0.62–2.11) | 1.16 (0.62–1.51) |

|

| |||

| sTNFR1 | 6183 (4698–7521) | 8460 (6062–11896) | 11161 (7750–17216) |

|

| |||

| TIM3 | 997 (621–1435) | 1990 (971–3615) | 3292 (1712–4380) |

|

| |||

| VEGF | 55 (36–83) | 46 (36–71) | 39 (35–50) |

|

| |||

| TNFα | 5.9 (4.3–9.8) | 6.1 (4.6–9.3) | 5.4 (3.9–7.8) |

|

| |||

| ST2 | 342 (225–588) | 689 (375–1388) | 1095 (326–2832) |

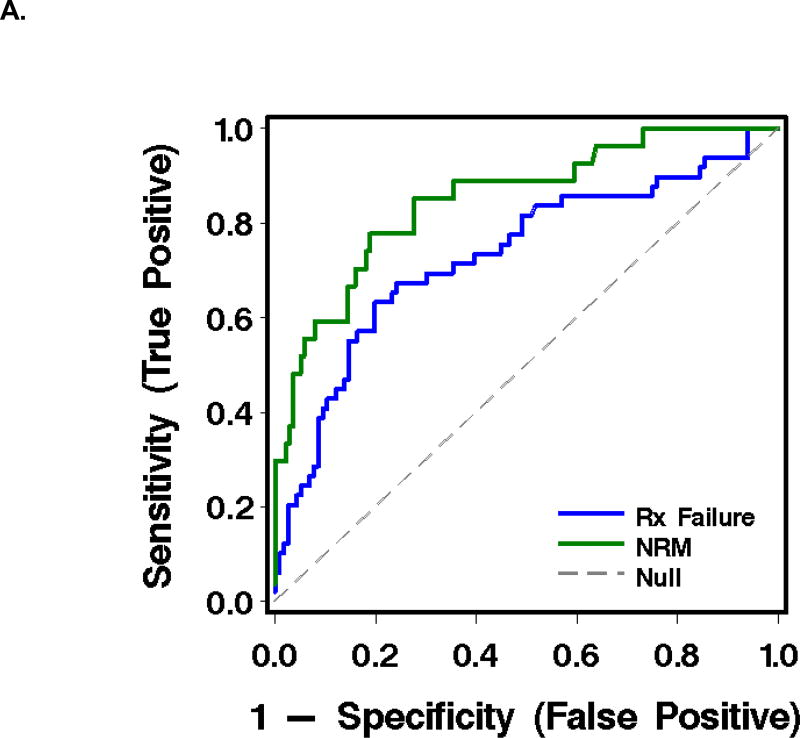

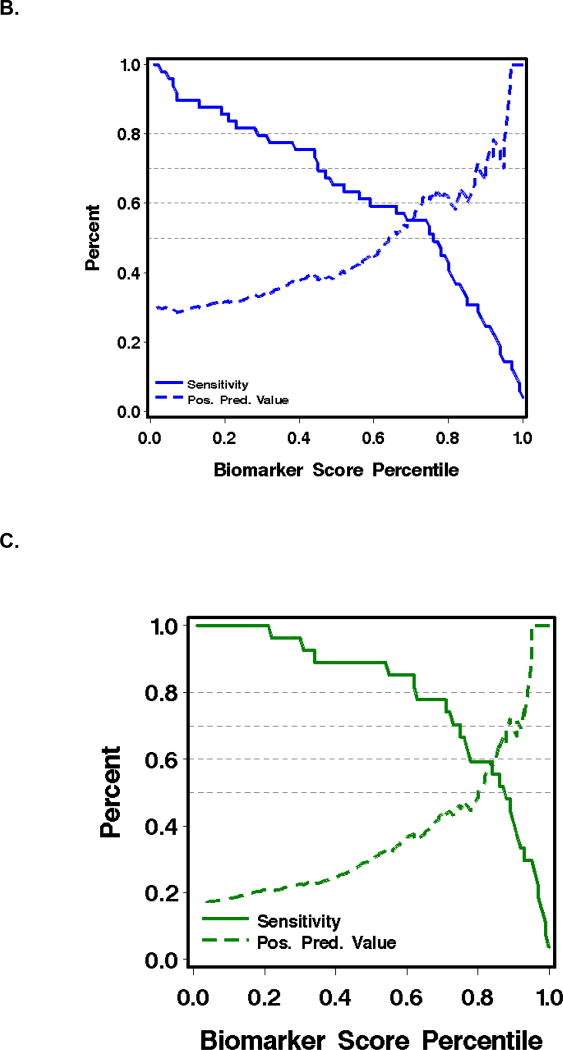

As judged by the area under a receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC), the most informative combination of plasma analytes for predicting failure of initial GVHD treatment was TIM3 and ST2 (AUC 0.73). The most informative combination for predicting NRM at 1 year after the plasma sample was drawn was sTNFR1 and TIM3 (AUC 0.85) (Table 3, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves and graphics of sensitivity and positive predictive value for biomarkers in plasma at treatment day 14 for the prediction of outcomes in patients with acute GVHD (see Table 3).

A. ROC curves, where the blue line represents operating characteristics of (TIM3 + ST2) for prediction of GVHD treatment failure, and the green line, (TIM3 + sTNFR1) for prediction of NRM.

B. Sensitivity (solid lines) and positive predictive value (dashed lines) of (TIM3 + ST2) for predicting failure of initial GVHD treatment.

C. Sensitivity (solid lines) and positive predictive value (dashed lines) of (TIM3 + sTNFR1) for predicting NRM within one year after day 14 of treatment.

Plasma biomarker, clinical, and demographic combinations and study outcomes

Of the clinical parameters after 14 days of GVHD therapy, only total serum bilirubin and serum albumin demonstrated AUC >0.70 as individual predictors of non-relapse mortality (Table 4). Combinations of clinical findings after 14 days of treatment had higher AUCs than individual predictors (Table 4). For the outcome ‘GVHD treatment failure’, the best clinical combination (total serum bilirubin and skin GVHD stage, AUC 0.70) was competitive with the best biomarker combination (TIM3 and ST2, AUC 0.73). The combination of best clinical and best biomarker findings (TIM3, ST2, total serum bilirubin, and skin GVHD stage) offered only a slight improvement (AUC 0.75) (Table 3). For the outcome ‘NRM at 1 year’, the best clinical predictor (total serum bilirubin, AUC 0.81) was competitive with the best biomarker combination (TIM3 and sTNFR1, AUC 0.85). The combination of best clinical and best biomarker findings (TIM3, sTNFR1, and total serum bilirubin, AUC 0.85) offered no improvement in AUC (Table 4).

Table 4.

Operating characteristics (AUCROC) for predicting GVHD treatment failure and NRM by one year later, for each plasma biomarker and each clinical and laboratory finding after 14 days of GVHD treatment.

| Prediction of GVHD treatment failure1 (n=49) |

Prediction of non-relapse mortality2 (n=27) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUCROC | p-value | AUCROC | p-value | |

| Plasma biomarkers | ||||

| ANG-2 | 0.58 | 0.11 | 0.71 | <0.0001 |

| HGF | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 0.20 |

| IL6 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.07 |

| sTNFRI | 0.67 | 0.0001 | 0.81 | <0.0001 |

| TIM3 | 0.68 | <0.0001 | 0.83 | <0.0001 |

| VEGF | 0.53 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.07 |

| TNFα | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.19 |

| ST2 | 0.73 | <0.0001 | 0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Best combination of plasma biomarkers3 | ||||

| TIM3 + ST2 | 0.73 | <0.0001 | ||

| sTNFRI + TIM3 | 0.85 | <0.0001 | ||

| Clinical and laboratory findings | ||||

| Gut GVHD stage4 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.02 |

| Change in gut GVHD stage | 0.51 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.85 |

| Skin GVHD stage4 | 0.61 | 0.0007 | 0.57 | 0.14 |

| Change in skin GVHD stage | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

| Total serum bilirubin4 | 0.66 | <0.0001 | 0.81 | <0.0001 |

| Change in total serum bilirubin | 0.56 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.11 |

| Serum albumin4 | 0.61 | 0.004 | 0.73 | <0.0001 |

| Change in serum albumin | 0.54 | 0.73 | 0.49 | 0.68 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate4 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 0.76 |

| Change in estimated glomerular filtration rate | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.59 | 0.10 |

| Prednisone dose4 | 0.55 | 0.19 | 0.62 | 0.14 |

| Change in prednisone dose | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.34 |

| Overall assessment of response4,5 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.20 |

| Time from day 0 to day of initial prednisone therapy | 0.58 | 0.13 | 0.58 | 0.17 |

| HLA mismatch | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.45 |

| Best combination of clinical and laboratory findings3 | ||||

| Total serum bilirubin + skin GVHD stage | 0.70 | <0.0001 | -- | -- |

| Total serum bilirubin | -- | -- | 0.81 | <0.0001 |

| Combination of best plasma biomarkers and best clinical /laboratory findings | ||||

| TIM3 + ST2 + total serum bilirubin + skin GVHD stage | 0.75 | <0.0001 | -- | -- |

| STNFR1 + TIM3 + total serum bilirubin | -- | -- | 0.85 | <0.0001 |

See Methods. Failure of initial GVHD treatment through day 56 of treatment meant death, or secondary therapy, or NIH cGVHD, or prednisone ≥0.5 mg/kg/day on days 55 and 56 of treatment.

Within 1 year after day 14 of treatment.

Based on forward selection among factors with 0.05 significance threshold.

At the time of the collection of the blood sample after 14±7 days of GVHD treatment.

Based on a global assessment of the course of GVHD from baseline (improved, worsened, or unchanged) (see Methods).

Overall clinical response to prednisone therapy at the time of the day-14 biomarker sample (as improved, worsened, or unchanged from baseline) was an inaccurate predictor of outcomes (Table 3). 153 (93%) were judged to have improved, 7 (4%) were worse, and 5 (3%) were unchanged. AUCs for predicting GVHD treatment failure and NRM based on clinical assessment of overall response were 0.55 and 0.53, respectively.

Could these data improve patient care by identifying patients with acute GVHD that is unlikely to respond to treatment with prednisone alone? Figure 2B shows that at a positive predictive value (PPV) of 80% for GVHD treatment failure, as might be required for a high-risk intervention at day 14 of therapy, the corresponding sensitivity is only 8%. Thus, the best biomarker combination would fail to identify over 90% of the patients who could benefit from an effective therapy. Similarly, Figure 2C shows that at a PPV of 80% for predicting NRM at one year, sensitivity is 30%. Thus, the panel would fail to identify 70% of the patients who could benefit. False positive predictions at treatment day 14 are also a problem, because the penalty to be paid for higher dose and prolonged immune suppression is the risk of fatal infection. Improved GVHD as judged clinically after 14 days of treatment also has poor predictive value and would incur a penalty if prednisone doses were inappropriately tapered in patients whose treatment is destined to fail.

Causes of non-relapse mortality to 1 year after the biomarker blood draw

The root cause of death in 26 of 27 non-relapse deaths was GVHD. The exception was patient #21 (Supplement Table S2) whose initial GVHD treatment was successful, such that GVHD was quiescent and no longer required prednisone at the time of death from respiratory failure and pulmonary infiltrates. The proximate causes of death were infection in 19 patients, respiratory failure in 5 patients (4 in the setting of systemic infection), multiorgan failure following sepsis in 2 patients, and GVHD in 1 patient (#19, Table S2). When infection was the proximate cause of death, the organisms responsible were molds (n=4), viruses (n=3), bacteria (n=3), multiple organisms (n=6), and organisms not identified (n=3).

Discussion

The principal findings of the current study are the following: 1) The best predictor of GVHD treatment failure after 14 days of prednisone therapy was a combination of plasma TIM3 and ST2, total serum bilirubin, and skin GVHD stage, but the operating characteristics of this combination offered only a slight improvement over either plasma biomarker or clinical findings alone. 2) In predicting NRM during the following year, total serum bilirubin at treatment day 14 was competitive with the combination of plasma TIM3 and sTNFR1, but combining serum bilirubin level with TIM3 and sTNFR1 offered no improvement in predictive value. 3) The dominant proximate cause of non-relapse deaths was infection, with the root cause attributed to GVHD in essentially all cases. The link between GVHD and death did not appear to be consistently related to the activity or severity of GVHD during the weeks to months before death. The dominant organisms causing fatal infection were viruses and fungi.

We speculate that prediction of GVHD treatment failure and NRM using plasma biomarker and clinical parameters lacks ideal sensitivity and specificity because of variation in the severity of immune dysfunction secondary to GVHD and its treatment, along with variable host susceptibility to opportunistic infection. Given the high rate of fatal infection, It seems unlikely that more intense immune suppression triggered by predictive markers at either GVHD onset or treatment day 14 would substantially reduce NRM. Investigational approaches to controlling the severity of GVHD without more intense immune suppression include biological drugs shown to be effective in Crohn’s Disease24, for example, limiting access of immune cells to gastrointestinal mucosa (www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT02133924 and NCT02728895), restoring intestinal barrier function by stimulation of the wnt pathway (NCT00408681) or infusion of IL22 (NCT02406651 ).25–28

We previously found that levels of TIM3, IL6, sTNFR1, and ST2 at the clinical onset of GVHD predicted the development of more severe GVHD and non-relapse mortality.20 The proportions of patients in the outcome categories grade 3–4 GVHD and non-relapse mortality were low, reflecting current incidence rates. Because such outcomes are infrequent, the positive predictive value of the best combination of analytes was 40% for predicting grade 3–4 GVHD and 50% for NRM at one year. If more aggressive immune suppressive therapies were to be instituted at GVHD onset based on these biomarkers, approximately half of patients treated in this manner would receive unnecessary and potentially risky therapy. The problem of suboptimal predictive values is true for all biomarker panels for GVHD outcomes published to date.

Our intent in defining prolonged exposure to prednisone as a criterion for GVHD treatment failure as was to codify what clinical experience and prior validated studies have demonstrated: inability to wean patients off prednisone is an independent risk factor for non-relapse mortality.29 We chose treatment day 14 because indications that initial treatment will fail are often apparent by that time, especially in patients with more severe gastrointestinal GVHD.30,31 At our institution, initiation of secondary therapy seldom begins before 14 days of treatment; in fact, no patient in this study started secondary therapy before the day 14 sample day. The use of treatment day 14 for blood sampling also has the advantage of increasing the time between the completion of conditioning therapy and the blood sample, thereby avoiding the confounding effects of regimen-related toxicity on plasma biomarkers. Our study has limitations, including the issue of overfitting our predictive model and the lack of an independent validation set. However, we are not proposing the use of any predictive model, with or without biomarkers. In fact, we conclude that even these potentially overfit models lack clinical utility (see Figures 2B and 2C).

Our findings are consistent with recent studies that have identified plasma TIM3, sTNFR1 and ST2 as informative for identifying patients at risk for more severe GVHD and mortality.3,15–17,19,20 A study of cord blood recipients at day 28 after transplantation showed that ST2 was predictive of transplant-related mortality and grade 3–4 GVHD.17 In another analysis of day 28 samples, ST2 and TIM3 were significantly associated with non-relapse mortality at 2 years.19 Analysis of plasma sTNFR1, Reg3α, and ST2 at GVHD diagnosis led to an algorithm that predicted NRM 6 months later.3,32 In another study, serum levels of the inflammatory biomarkers B-cell activating factor, IL33, and C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligands (CXCL) 10 and 11 were elevated in patients with acute GVHD, but were not compared to other cytokine/chemokine panels.33 TIM3 has now been identified as a predictor of more severe GVHD and mortality before the onset of GVHD symptoms, at day 28 after transplantation, and after 14 days of GVHD treatment with glucocorticoids.19,20,23 In each of these cohort studies, the PPVs for association with clinical outcomes were less than 50%.

The most informative plasma biomarkers (ST2, TIM3, and sTNFR1) each represent a cell-surface receptor with dual immune functions by mediating signaling in its membrane-bound form and serving as a decoy with regulatory activity in its soluble form.34–37 At treatment day 14, these markers of counter-regulatory mechanisms are more predictive of adverse outcomes than pro-inflammatory markers. Elevation of total serum bilirubin is well-recognized as a marker of more severe GVHD and mortality.31,38 In early GVHD, the mechanism of hyperbilirubinemia involves dislocation of bilirubin transport proteins from hepatocyte canalicular membranes as a result of exposure to IL6 and TNFα.20,39–41

We conclude that after initial glucocorticoid therapy, the plasma biomarkers TIM3, ST2, sTNFR1, total serum bilirubin, and skin GVHD can predict failure of GVHD treatment and non-relapse mortality. These data fulfill some of the necessary criteria for bringing biomarker measurements into clinical practice.42 The ultimate goal of accurately predicting outcomes of patients with acute GVHD, however, remains elusive because the best predictive models would identify only a minority of patients with high-risk GVHD, and most patients would be falsely predicted to have adverse outcomes. Although the biomarkers associated with GVHD outcomes to date do not provide optimal positive and negative predictive value, they point to counter-regulatory mechanisms in the pathophysiology of the disease and have identified targets for testing in clinical trials.34

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

For predicting failure after 14 days of GVHD treatment, total serum bilirubin and skin GVHD stage (AUC 0.70) was competitive with the biomarker combination TIM3 and ST2 (AUC 0.73).

For predicting NRM at 1 year, total serum bilirubin (AUC 0.81) was competitive with the biomarker combination TIM3 and sTNFR1 (AUC 0.85).

Among these GVHD-associated deaths, infection was the proximate cause of non-relapse mortality in essentially all cases.

The best predictive models identify only a minority of patients with high-risk GVHD; most are falsely predicted to have adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Our research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA18029, CA15704, CA 78902, AI33484, HL094260, HL122173).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authorship contributions:

George McDonald co-designed the study, assisted in data analysis and interpretation, performed cause of death determinations, and wrote the manuscript.

Laura Tabellini collected and processed the blood samples, collected clinical data while blinded to study outcomes, and reviewed the manuscript.

Barry Storer did the statistical analyses, prepared the graphics related to receiver-operating characteristic curves and sensitivity/specificity analyses, and edited the manuscript.

Paul Martin co-designed the study, assisted in data analysis and interpretation, and edited the manuscript.

Richard Lawler processed plasma samples and performed the assays of biomarkers.

Steven Rosinski collected clinical data after 14 days of prednisone therapy while blinded to study outcomes, and reviewed the manuscript.

Gary Schoch prepared tabular displays of demographic information and laboratory parameters that were analyzed by Barry Storer, and prepared data displays of clinical findings that were collected by Laura Tabellini and Steven Rosinski.

John Hansen co-designed the study, assisted in data analysis and interpretation, and edited the manuscript.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest. No author has a conflict of interest with regard to the contents of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2091–101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald GB. How I treat acute graft-versus-host disease of the gastrointestinal tract and the liver. Blood. 2016;127:1544–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-612747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine JE, Braun TM, Harris AC, et al. A prognostic score for acute graft-versus-host disease based on biomarkers: a multicenter study. The Lancet Haematology. 2015;2:21–9. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(14)00035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciurea SO, Zhang MJ, Bacigalupo AA, et al. Haploidentical transplant with posttransplant cyclophosphamide vs matched unrelated donor transplant for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;126:1033–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-639831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacoby E, Chen A, Loeb DM, et al. Single-agent post-transplantation cyclophosphamide as Graft-versus-Host Disease prophylaxis after Human Leukocyte Antigen-matched related bone marrow transplantation for pediatric and young adult patients with hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanakry CG, Fuchs EJ, Luznik L. Modern approaches to HLA-haploidentical blood or marrow transplantation. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2016;13:10–24. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mielcarek M, Furlong T, O’Donnell PV, et al. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for prevention of graft-versus-host disease after HLA-matched mobilized blood cell transplantation. Blood. :2016. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-672071. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleakley M, Heimfeld S, Loeb KR, et al. Outcomes of acute leukemia patients transplanted with naive T cell-depleted stem cell grafts. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015;125:2677–89. doi: 10.1172/JCI81229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersdorf EW, Malkki M, O'HUigin C, et al. High HLA-DP Expression and Graft-versus-Host Disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:599–609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin PJ, Levine DM, Storer BE, et al. Genome-wide minor histocompatibility matching as related to the risk of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2016 doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-737700. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holtan SG, MacMillan ML. A risk-adapted approach to acute GVHD treatment: are we there yet? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:172–5. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mielcarek M, Furlong T, Storer BE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of lower dose prednisone for initial treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: a randomized controlled trial. Haematologica. 2015;100:842–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.118471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hockenbery DM, Cruickshank S, Rodell TC, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oral beclomethasone dipropionate as a prednisone-sparing therapy for gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2007;109:4557–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castilla C, Perez-Simon JA, Sanchez-Guijo FM, et al. Oral beclomethasone dipropionate for the treatment of gastrointestinal acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) Biology of Blood & Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:936–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paczesny S. Discovery and validation of graft-versus-host disease biomarkers. Blood. 2013;121:585–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-355990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vander Lugt MT, Braun TM, Hanash S, et al. ST2 as a marker for risk of therapy-resistant graft-versus-host disease and death. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:529–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponce DM, Hilden P, Mumaw C, et al. High day 28 ST2 levels predict for acute graft-versus-host disease and transplant-related mortality after cord blood transplantation. Blood. 2015;125:199–205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-584789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holtan SG, Verneris MR, Schultz KR, et al. Circulating Angiogenic Factors associated with Response and Survival in Patients with Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease: Results from Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network 0302 and 0802. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu Zaid M, Wu J, Wu C, et al. Plasma biomarkers of risk for death in a multicenter phase 3 trial with uniform transplant characteristics post-allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2017;129:162–170. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-735324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald GB, Tabellini L, Storer BE, Lawler RL, Martin PJ, Hansen JA. Plasma biomarkers of acute GVHD and nonrelapse mortality: predictive value of measurements before GVHD onset and treatment. Blood. 2015;126:113–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-636753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin PJ, Schoch G, Fisher L, et al. A retrospective analysis of therapy for acute graft-versus-host disease: initial treatment. Blood. 1990;76:1464–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dietrich S, Falk CS, Benner A, et al. Endothelial vulnerability and endothelial damage are associated with risk of graft-versus-host disease and response to steroid treatment. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen JA, Hanash SM, Tabellini L, et al. A novel soluble form of Tim-3 associated with severe graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sands BESC. Crohn’s Disease. In: Feldman MFL, Brandt LJ, editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology / Diagnosis / Management. Tenth. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016. pp. 1990–2022. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindemans CA, Calafiore M, Mertelsmann AM, et al. Interleukin-22 promotes intestinal-stem-cell-mediated epithelial regeneration. Nature. 2015;528:560–4. doi: 10.1038/nature16460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peled JU, Hanash AM, Jenq RR. Role of the intestinal mucosa in acute gastrointestinal GVHD. Blood. 2016;128:2395–402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-06-716738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldman E, Lu SX, Hubbard VM, et al. Absence of beta7 integrin results in less graft-versus-host disease because of decreased homing of alloreactive T cells to intestine. Blood. 2006;107:1703–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YB, Kim HT, McDonough S, et al. Up-Regulation of alpha4beta7 integrin on peripheral T cell subsets correlates with the development of acute intestinal graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1066–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leisenring W, Martin P, Petersdorf E, et al. An acute graft-versus-host disease activity index to predict survival after hematopoietic cell transplantation with myeloablative conditioning regimens. Blood. 2006;108:749–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castilla-Llorente C, Martin PJ, McDonald GB, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes of severe gastrointestinal GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:966–71. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Lint MT, Milone G, Leotta S, et al. Treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease with prednisolone: significant survival advantage for day +5 responders and no advantage for nonresponders receiving anti-thymocyte globulin. Blood. 2006;107:4177–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renteria AS, Levine JE, Ferrara JL. Development of a biomarker scoring system for use in graft-versus-host disease. Biomarkers in medicine. 2016;10:793–5. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2016-0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed SS, Wang XN, Norden J, et al. Identification and validation of biomarkers associated with acute and chronic graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1563–71. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Ramadan AM, Griesenauer B, et al. ST2 blockade reduces sST2-producing T cells while maintaining protective mST2-expressing T cells during graft-versus-host disease. Science translational medicine. 2015;7:308ra160. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichenbach DK, Schwarze V, Matta BM, et al. The IL-33/ST2 axis augments effector T-cell responses during acute GVHD. Blood. 2015;125:3183–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-606830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter ER, McKenzie AN, Lee RT. IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:1538–49. doi: 10.1172/JCI30634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Locksley RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gooley TA, Rajvanshi P, Schoch HG, McDonald GB. Serum bilirubin levels and mortality after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:345–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.20529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malone FR, Leisenring W, Schoch G, et al. Prolonged anorexia and elevated plasma cytokine levels following myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:765–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Vee M, Lecureur V, Stieger B, Fardel O. Regulation of drug transporter expression in human hepatocytes exposed to the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha or interleukin-6. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2009;37:685–93. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shulman HM, Sharma P, Amos D, Fenster LF, McDonald GB. A coded histologic study of hepatic graft-versus-host disease after human marrow transplantation. Hepatology. 1988;8:463–70. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ito S, Barrett AJ. ST2: the biomarker at the heart of GVHD severity. Blood. 2015;125:10–1. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-611780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.