Although the weight of evidence does not support major clinical differences, the substantial physiological, circadian, and psychosocial challenges of the perinatal period portend a worse clinical outcome for vulnerable women.

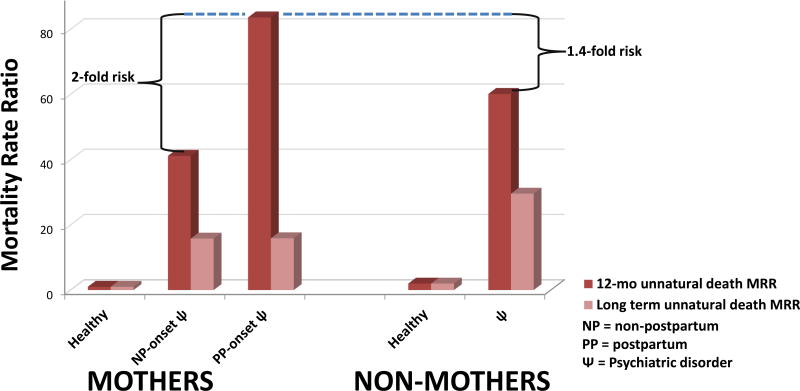

Maternal psychiatric illness is a major public health concern and has far-reaching effects on the development of future generations (1). Maternal suicide that occurs in the postpartum period is a tragedy that has often been in the media spotlight (e.g., [2]), and it is an important feature of the compelling Danish registry linkage study by Johannsen et al. in this issue (3). The most poignant finding of this study is the greatly elevated 1-year risk of suicide, measured by a mortality rate ratio (MRR) of 289, in women with onset of psychiatric illness within 90 days postpartum, relative to healthy mothers (reference group MRR, 1). Equally dramatic but more unexpected are the high MRR values reported for childless women with psychiatric illness. Following the elevated 1-year suicide risk among mothers with postpartum psychiatric disorders, mentally ill childless women had the greatest all-cause mortality risk and greatest long-term mortality risk from suicide or accidents (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

12-Month and Long-Term Mortality Risk From Unnatural Causes (Suicide and Accidents) in Five Comparison Categories

The study harnesses a cohort of more than 1.5 million women, with data for up to 42 years of life per individual, obtained through the linkage of four Danish population registers, bringing together demographic, psychiatric, medical, and cause-of-death data. This study represents an unparalleled opportunity to rigorously examine associations between mental health and mortality among five female comparison groups: mothers and nonmothers with and without psychiatric illness and with and without 90-day postpartum illness onset. The MRR is a sophisticated outcome measure that is age-specific and adjusts for other time-dependent variables (i.e., medical comorbidity). However, the MRR may be unstable for low prevalent (N<20) outcomes such as suicide and may overestimate the short-term risk of suicide, because this cause of death is more common in younger cohorts, especially after receiving a new psychiatric diagnosis (4). Mortality rates can also be influenced by misclassification of suicides as accidents. When accident-related causes of death and suicides were combined (“unnatural-cause mortality”), the 1-year MRR in postpartum psychiatrically ill women decreased substantially from 289 to 83.6. Nevertheless, the 1-year unnatural-cause mortality risk was twofold greater for mothers with first-onset 90-day postpartum psychiatric disorders relative to mothers with psychiatric illness onset any time before or after the 90-day postpartum window (Figure 1). The magnitude of this risk points to an urgent need for increased surveillance for suicide in mothers with onset of psychiatric disorders within 90 days postpartum.

The high suicide risk in mothers with new onset psychiatric illness reported here extends prior analysis (5) that revealed a 70-fold increased suicide risk following psychiatric hospitalization in the first postnatal year relative to the background population risk. The disproportionate suicide-specific 1-year mortality in women with postpartum onset of illness raises the age-old question of whether postpartum psychiatric disorders are nosologically different from disorders occurring at other times. Although the weight of evidence does not support major clinical differences, the substantial physiological, circadian, and psychosocial challenges of the perinatal period portend a worse clinical outcome for vulnerable women. The most frequent ICD-based diagnoses accounting for unnatural-cause mortality in mothers with postpartum-onset psychiatric disorders in this study (3) were schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders; followed by mental and behavioral disorders associated with the puerperium; affective disorders; and finally neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders. A similar pattern was reported by the U.K. Confidential Inquiry into perinatal unnatural-cause mortality (6). Furthermore, summaries of the U.K. Centre for Maternal and Child Inquiries highlight affective psychosis, bipolar disorder, and severe depression as diagnoses that carry 50% recurrence risk and warrant the greatest vigilance by clinicians across the perinatal period (7).

The demographic profile of perinatal suicide victims is known to be variable (6–8), with convergent evidence for higher than expected rates of older (>30 years), married, employed women living in stable housing, and women who are primiparous. On the other hand, perinatal suicide victims with drug or alcohol use disorders tend to be younger, single, poor, and living in unstable situations (7). Distinctive clinical features of mothers who have committed suicide include sudden symptom onset, rapid deterioration, and onset within the first several weeks postpartum. More than half of suicide victims had been in psychiatric care, including recent psychiatric inpatient admission, and an important minority of suicides were accounted for by women with less than 1 year duration of illness (6). Suicide methods among perinatal women were nearly always violent (90% of cases), and suicide occurred most often via asphyxiation (hanging or jumping) (7), demonstrating clear lethal intent compared with nonperinatal suicides, which generally involve less violent means. Postpartum suicide is accompanied by infanticide in 5% of cases (Friedman and Resnick, see reference below).

These powerful data must teach us to lower our threshold for concern for perinatal women with severe mental illness. A prior personal and family history of severe postpartum psychiatric illness, including affective psychosis, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, demands close monitoring and management throughout the perinatal period, and particularly in the first postpartum year. Despite numerous publications asserting a clear rationale for mentally ill perinatal women to continue psychotropic medications, many will discontinue their medications and thereby expose themselves to high risk of recurrence (9). The availability of specialized perinatal psychiatric teams who can provide a continuum of services and support mothers in risk-benefit discussions about psychotropic use in pregnancy and lactation remains an invaluable service to enhance wellness in new mothers. Furthermore, postpartum women hospitalized with these diagnoses must be carefully managed at the time of discharge by knowledgeable outpatient clinicians. The availability of inpatient and intensive outpatient mother-baby programs for psychiatrically ill women is critical to their care in ways that promote the development of positive mother-infant emotional ties, avoid the need to separate the mother from her child, and support and encourage mothers with (at time delusional) doubts about their ability to parent. It is certainly a daunting prospect to design an intervention strategy for a rare outcome such as suicide, and so it behooves all practitioners and community members to have their eyes wide open. Psychiatrists are not the only responsible party: obstetricians seeing women for 6-week postpartum checks and annual exams, pediatricians treating offspring, primary care physicians who come into contact with new mothers, family members, and friends all have the capacity to be on the alert for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in new mothers. Integrated behavioral health models in primary care settings also hold promise for more rapid identification and treatment of such patients.

Despite these grave concerns, it is noteworthy that Johannsen and colleagues report that motherhood was protective for survival as long as the onset of psychiatric disorder was not within 90 days postdelivery. Childless women with psychiatric disorders had the highest all-cause MRR and the greatest long-term mortality risk from suicide or accidents. If all-cause mortality was adequately adjusted for medical comorbidity, as expected by the rigorous use of linked medical databases and the Charlson comorbidity index, higher MRR in childless women with psychiatric disorders could have resulted from social or other unmeasured factors. Decreased survival from medical disease without the support of children, lack of social control of unhealthy behaviors in childless individuals, and selection against fertility among unhealthier women are possible explanations for higher MRR in childless women (10), with exacerbation of these factors in childless psychiatrically ill women. It is also conceivable that the mother-child relationship optimizes the physiology of stress and attachment to improve longevity. The hidden message in this article, therefore, is the importance of attending to the morbidity and mortality risks among the larger population of psychiatric patients in our care, as well as the need for support networks and rigorous monitoring of new mothers and childless women with new and chronic psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Moses-Kolko and Hipwell report support from NIH grants during the writing of this editorial. Dr. Hipwell also received support from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and from the Pennsylvania Department of Health during the writing of this editorial.

References

- 1.Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, et al. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belluck P. After baby, an unraveling: a case study in maternal mental illness. New York Times; Jun 17, 2014. p. D1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johannsen BM, Larsen JT, Laursen TM, et al. All-cause mortality in women with severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121510. xxx–xxx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bostwick JM, Pankratz VS. Affective disorders and suicide risk: a reexamination. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1925–1932. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appleby L, Mortensen PB, Faragher EB. Suicide and other causes of mortality after post-partum psychiatric admission. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:209–211. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalifeh H, Hunt IM, Appleby L, et al. Suicide in perinatal and non-perinatal women in contact with psychiatric services: 15 year findings from a UK national inquiry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:233–242. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 2011;118(Suppl 1):1–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold KJ, Singh V, Marcus SM, et al. Mental health, substance use and intimate partner problems among pregnant and postpartum suicide victims in the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:117–127. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy E, Kravdal O. Fertility history and cause-specific mortality: a register-based analysis of complete cohorts of Norwegian women and men. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:137–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]