Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Acinic cell carcinoma is a rare salivary neoplasm that is generally associated with a good prognosis, although a subset of patients develops local and distant recurrences. Given the rarity of the disease, factors to identify patients at risk for recurrences or decreased survival are not clearly defined.

OBJECTIVES

To identify clinicopathologic factors associated with adverse survival in patients with acinic cell carcinoma and to assess the effect of local, regional, and distant recurrences on survival.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Retrospective medical record review in a tertiary care cancer center of 155 patients treated for acinic cell carcinoma from January 1990 through February 2013.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Primary outcomes evaluated were overall and disease-free survival. The end points assessed were age at diagnosis, sex, size of primary tumor, presence of positive surgical margins, postoperative radiation therapy, and development of local, regional, or distant recurrences.

RESULTS

The median survival was 28.5 years, with 13 patients (8.4%) dying of their disease. Women (n = 104) were affected twice as often as men (n = 51) but had an improved survival (P < .001). Patients diagnosed as having acinic cell carcinoma before or at the age of 45 years had an improved survival (P = .02) compared with their elder counterparts, a finding that was independent of sex. Neoplasms larger than 3 cm at presentation were associated with a decreased overall survival compared with smaller lesions (P = .02). The development of distant metastases was most associated with death from the disease (odds ratio, 49.90; 95% CI, 6.49–2246.30; P <.001) compared with local and regional recurrences.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Although patients with acinic cell carcinoma generally have a favorable prognosis, we have identified several factors associated with decreased survival, including male sex, age older than 45 years, neoplasms larger than 3 cm, and the development of a distant recurrence. These results suggest that maximizing local and regional control for this disease can offer substantial benefit when no distant disease is detectable.

Salivary gland neoplasms represent 2% to 7% of all head and neck neoplasms but only 0.3% of malignant neoplasms.1–3 Acinic cell carcinoma (ACC) comprises approximately 3% to 9% of all salivary gland neoplasms and up to 17% of salivary gland malignant neoplasms.2,4 Most ACCs occur in the parotid gland and infrequently involve the minor salivary and submandibular glands.2,5 Although most ACCs are composed of several cell types, the predominant cell variety is acinic serous cells with zymogen-secreting granules.2

Although early controversies questioned the malignant nature of acinic cell tumors because of their slow growth patterns, pathologic features, and clinical behavior, several studies6,7 demonstrated the propensity of this tumor for lymphatic and distant metastasis. Initial studies on ACC indicated that histologic grade had little significance as a predictor of prognosis, yet more recent studies4,5,8 have found that high-grade malignant neoplasms are associated with advanced-stage disease, higher incidence of distant metastasis, and poorer 5-year survival.

Because of the rarity of this disease, few studies5,9,10 have comprehensively assessed the prognosis of ACC with respect to risk factors, histologic features, stage, site, and treatment. The goals of this study were to identify clinicopathologic factors associated with adverse survival in patients with ACC and to assess the effect of local, regional, and distant recurrences on survival.

Methods

After approval from the institutional review board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, a retrospective medical record review identified 155 patients who were treated for ACC from January 1990 through February 2013. The primary outcomes assessed were overall and disease-free survival. The end points studied to assess these outcomes included sex, age at diagnosis, disease status at time of presentation, T stage, N stage, size of primary tumor, the presence of positive surgical margins, the extent of surgery, and the addition of postoperative radiation therapy. In addition, the effect of the site of a recurrence on overall survival was evaluated. Persistent disease was defined as a patient with incomplete or inadequate initial therapy that required a revision procedure to achieve the surgical standard of care. Positive surgical margins were defined as macroscopically or microscopically positive or close margin less than 5 mm. The indications for radiation therapy in this series were recurrent disease, positive surgical margins, presence of cervical lymph nodes, perineural invasion, high-grade tumors, and T3 or T4 primaries. All tumors were assessed by a head and neck pathologist.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs were calculated to assess the odds of death from disease. The χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to assess significance for an association between the patient characteristics and death from disease. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were built to estimate the hazard ratios and 95% CIs of the prognostic factors considered for overall survival and disease-free survival.11 The proportional hazards assumptions were checked. Multivariate models adjusting for prognostic factors were built using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. To identify the most significant predictors, models including all variables were initially fitted and then reduced in a stepwise manner to identify the best fit according to the Akaike information criterion.12 The likelihoods of the full and reduced model were compared using the χ2 test to decide whether the additional variable present in the full model significantly improved the fit. Predictors with P<.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.0.0 statistical software (Lucent Technologies Inc) using a Mac OS X 10.8.4 computer (Apple Corp).

Results

Demographics

One hundred fifty-five patients were identified, with a mean follow-up of 6.8 years (range, 0.2–38 years). The mean age at presentation was 52 years (range, 11–100 years). Ninety-six patients were older than 45 years, and 59 patients were 45 years or younger. Female patients were twice as likely to have ACC compared with male patients (Table 1). Given the high referral rate seen at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, most patients presented with persistent (54.1%) or recurrent disease (29.0%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate Cox Proportional Hazard Regression Models for Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Acinic Cell Carcinoma

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Disease Free | ||||

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Age, y | |||||

| ≤45 (reference) | 59 | … | … | … | … |

| >45 | 96 | 2.98 (1.15–7.74) | .03 | 1.68 (0.95–2.95) | .07 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female (reference) | 104 | … | … | … | … |

| Male | 51 | 3.61 (1.80–7.24) | <.001 | 1.53 (0.94–2.47) | .09 |

| Presentation | |||||

| Untreated and persistent (reference) | 110 | … | … | … | … |

| Recurrence | 45 | 1.50 (0.75–2.98) | .25 | 3.72 (2.30–6.03) | <.001 |

| Tumor size, cm | |||||

| ≤3 (reference) | 49 | … | … | … | … |

| >3 | 31 | 2.92 (1.13–7.52) | .03 | 2.40 (1.12–5.14) | .02 |

| Unknown | 75 | 1.07 (0.45–2.50) | .88 | 1.88 (1.01–3.52) | .048 |

| T stage | |||||

| 1 and 2 (reference) | 69 | … | … | … | … |

| 3 and 4 | 19 | 2.67 (1.09–6.57) | .03 | 2.53 (1.19–5.37) | .02 |

| Unknown | 61 | 0.88 (0.39–1.95) | .75 | 1.99 (1.13–3.51) | .02 |

| X | 6 | 0.43 (0.05–3.40) | .43 | 1.29 (0.37–4.23) | .69 |

| N stage | |||||

| N0 and N1 (reference) | 121 | … | … | … | … |

| N2 and N3 | 6 | 2.78 (0.64–11.97) | .17 | 1.11 (0.27–4.59) | .88 |

| Unknown | 28 | 1.87 (0.88–3.99) | .10 | 2.17 (1.29–3.65) | .004 |

| Parotidectomy | |||||

| Enucleation and superficial (reference) | 81 | … | … | … | … |

| Total | 52 | 1.36 (0.63–2.94) | .44 | 1.58 (0.93–2.68) | .09 |

| Unknown | 22 | 2.21 (0.92–5.27) | .08 | 1.73 (0.90–3.33) | .10 |

| Neck dissection | |||||

| No (reference) | 109 | … | … | … | … |

| Yes | 38 | 1.62 (0.76–3.47) | .21 | 1.22 (0.70–2.11) | .48 |

| Unknown | 8 | 3.57 (1.21–10.55) | .02 | 1.80 (0.71–4.56) | .21 |

| Positive margins | |||||

| No (reference) | 103 | … | … | … | … |

| Yes | 52 | 1.76 (0.86–3.62) | .12 | 1.31 (0.78–2.22) | .31 |

| Radiation therapy | |||||

| No (reference) | 73 | … | … | … | … |

| Yes | 75 | 1.88 (0.93–3.79) | .08 | 1.40 (0.86–2.27) | .18 |

| Unknown | 7 | 3.49 (0.44–27.47) | .24 | 1.11 (0.15–8.20) | .92 |

Abbreviation: Ellipses indicate data not applicable.

Most patients presented with parotid masses, whereas only 3.X% of neoplasms arose from the submandibular gland, and most patients presented with stage I and II disease (Table 1). For cases where tumor dimensions were available, lesions smaller than 3 cm were slightly more common than larger tumors (Table 1). As expected for ACC, nodal metastases were rarely identified.

Treatment

Patients underwent a spectrum of surgical procedures, most commonly a superficial parotidectomy (54.1%). However, given the high rate of recurrent and persistent disease in this series, a substantial number of patients underwent total parotidectomies (39.1%) (Table 1). Neck dissection was performed in 25.9% of patients. Pathologically, close or positive surgical margins were observed in nearly half of the patients. Adjuvant radiation therapy was administered to 50.7% of patients.

Outcomes

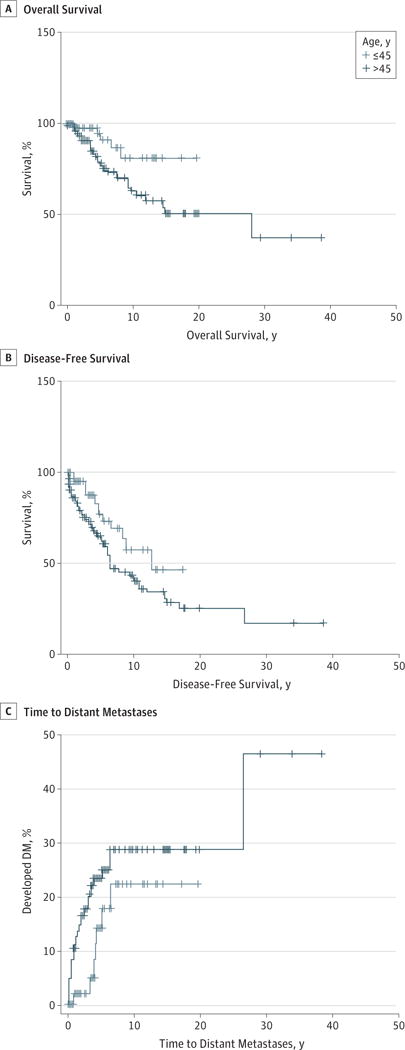

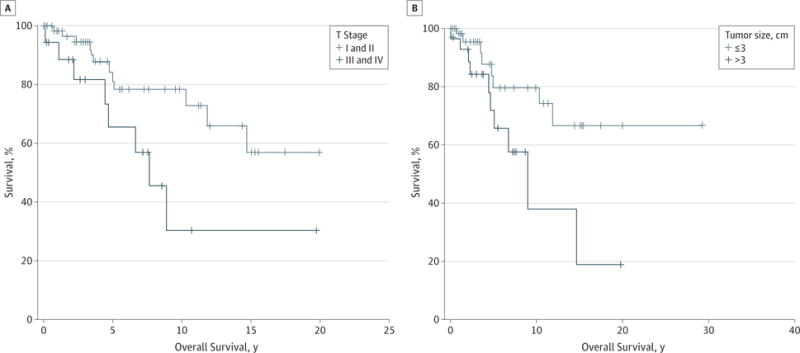

Patients older than 45 years had a significantly decreased overall and disease-free survival compared with their younger counterparts (P = .02 and .03, respectively) (Figure 1A and B). These survival differences appeared to be due to a higher incidence of distant metastases that was seen in the older population (Figure 1C). Although ACC is more common in the female population, women had an improved overall survival, independent of stage, and were less likely to die of their disease (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4). The presence of persistent disease did not have an effect on survival, whereas the development of a recurrence portended an adverse prognosis, with decreased disease-free survival and an increased likelihood of death from disease (Tables 1 through 4). Among patients who presented with cervical lymphadenopathy, there was an increased risk of death from disease compared with patients with N0 disease (Table 4). Patients with stage I and II disease not only had significantly improved overall and disease-free survival but also had a decreased risk of death from disease (Figure 2 and Tables 1 through 4). The size of the primary tumor appeared to be equivalently prognostic of survival as clinical stage because patients with tumors larger than 3 cm had a significantly decreased survival compared with patients with smaller tumors (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 1. Effect of Age on Survival.

Patients older than 45 years (n = 96) have a decreased overall (A) and disease-free survival (B) with an increased rate of distant metastases (DM) (C) compared with patients 45 years and younger (n = 59). Log rank tests confirmed that the overall and disease-free survival curves were significantly different (P = .02 and .03, respectively). The curve for time to distant metastases was not statistically significant (P = .14).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Models for Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Overall Survival in Patients With Acinic Cell Carcinoma

| Characteristic | No. of Patients (N=155) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| ≤45 (reference) | 59 | … | … |

| >45 | 96 | 3.10 (1.16–8.29) | .02 |

| Sex | |||

| Female (reference) | 104 | … | … |

| Male | 51 | 3.14 (1.55–6.36) | .002 |

| Tumor size, cm | |||

| ≤3 (reference) | 49 | … | … |

| >3 | 31 | 2.55 (1.18–5.53) | .02 |

| Positive margins | |||

| No (reference) | 103 | … | … |

| Yes | 52 | 2.16 (1.01–4.62) | .048 |

Abbreviation: Ellipses indicate data not applicable.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Models for Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Disease-Free Survival in Patients With Acinic Cell Carcinoma

| Characteristic | No. of Patients (N=155) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation | |||

| Untreated and persistent (reference) | 110 | … | … |

| Recurrence | 45 | 4.22 (2.53–7.046) | <.001 |

| T stage | |||

| 1 and 2 (reference) | 69 | … | … |

| 3 and 4 | 19 | 2.13 (1.06–4.29) | .03 |

| Radiation therapy | |||

| No (reference) | 73 | … | … |

| Yes | 75 | 1.85 (1.09–3.12) | .02 |

Abbreviation: Ellipses indicate data not applicable.

Table 4.

Odds Ratio of Death From Acinic Cell Carcinoma

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | Death From Disease | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| All patients | 155 | 13 | 142 | … | … |

| Age, y | |||||

| ≤45 (reference) | 59 | 57 | 2 | … | … |

| >45 | 96 | 85 | 11 | 3.66 (0.76–35.24) | .13 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female (reference) | 104 | 99 | 5 | … | … |

| Male | 51 | 43 | 8 | 3.65 (0.99–15.04) | .03 |

| Presentation | |||||

| Untreated and persistent (reference) | 110 | 106 | 4 | … | … |

| Recurrence | 45 | 36 | 9 | 6.53 (1.70–30.81) | .002 |

| Tumor size, cm | |||||

| ≤3 (reference) | 49 | 47 | 2 | … | … |

| >3 | 31 | 27 | 4 | 3.43 (0.46–40.23) | .20 |

| Unknown | 75 | 68 | 7 | 2.40 (0.43–24.71) | .48 |

| T stage | |||||

| 1 and 2 (reference) | 69 | 67 | 2 | … | … |

| 3 and 4 | 19 | 15 | 4 | 8.62 (1.12–103.62) | .02 |

| Unknown | 61 | 54 | 7 | 4.30 (0.78–44.05) | .08 |

| X | 6 | 6 | 0 | 2.08 | |

| N stage | |||||

| N0 and N1 (reference) | 121 | 115 | 6 | … | … |

| N2 and N3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 9.20 (0.70–81.59) | .053 |

| Unknown | 28 | 23 | 5 | 4.11 (0.91–17.76) | .051 |

| Positive margins | |||||

| No (reference) | 103 | 65 | 6 | … | … |

| Yes | 52 | 58 | 5 | 1.26 (0.31–4.66) | .76 |

| Parotidectomy | |||||

| Enucleation and superficial (reference) | 81 | 77 | 4 | … | … |

| Total | 52 | 46 | 6 | 2.49 (0.56–12.67) | .19 |

| Unknown | 22 | 19 | 3 | 3.00 (0.41–19.40) | .16 |

| Neck dissection | |||||

| No (reference) | 109 | 102 | 7 | … | … |

| Yes | 38 | 34 | 4 | 1.71 (0.34–7.21) | .48 |

| Unknown | 8 | 6 | 2 | 4.75 (0.40–34.15) | .12 |

| Radiation therapy | |||||

| No (reference) | 74 | 69 | 4 | … | … |

| Yes | 73 | 66 | 9 | 2.34 (0.62–10.91) | .24 |

| Unknown | 7 | 7 | 0 | 1.03 | |

| Recurrence | |||||

| None (reference) | 105 | 104 | 1 | … | … |

| Local | 31 | 26 | 5 | 19.42 (2.05–949.24) | .002 |

| Regional | 11 | 9 | 2 | 21.64 (1.04–1360.26) | .02 |

| Distant | 30 | 20 | 10 | 49.90 (6.49–2246.30) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: Ellipses indicate data not applicable.

P value based on the χ2 test or Fisher exact test.

Figure 2. Effect of Early vs Late T Stage and Tumor Size on Overall Survival.

A, Patients who presented with early-stage disease (stages I and II) (n = 69) had a significantly improved survival compared with patients with late-stage disease (P = .02) (n = 19). B, Patients with tumors larger than 3 cm also had a significantly decreased overall survival compared with smaller tumors (P = .04) (n = 31 and 49, respectively).

The extent of the surgery for the primary tumor did not affect overall or disease-free survival (Table 1, 2, and 3). Furthermore, the likelihood of developing a local recurrence was equivalent whether the patient underwent a superficial or total parotidectomy (odds ratio, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.55–3.12; P = .54) (Table 5). Despite the low frequency of regional disease, the addition of the neck dissection reduced the regional recurrence rate from 9% to 2% (Table 4). The presence of positive surgical margins did not affect survival or local recurrence (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 5). The addition of postoperative radiation did not improve overall or disease-free survival, and there was no effect on local or regional recurrences for patients treated for recurrent disease (Table 1, 2, 3, and 5), likely reflecting the nature of the patient population in this study.

Table 5.

Odds Ratios of Developing Local, Regional, or Distant Metastases

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | Recurrence | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | Regional | Distant | |||||||||||

| Yes | No | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Yes | No | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Yes | No | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| All patients | 155 | 31 | 124 | … | … | 11 | 144 | … | … | 30 | 125 | … | … |

| Age, y | |||||||||||||

| ≤45 (reference) | 75 | 14 | 61 | … | … | 4 | 71 | … | … | 8 | 67 | … | … |

| >45 | 80 | 17 | 63 | 1.18 (0.53–2.59) | .69 | 7 | 73 | 1.70 (0.48–6.07) | .41 | 22 | 58 | 3.18 (1.31–7.68) | .01 |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Female (reference) | 104 | 22 | 82 | … | … | 7 | 97 | … | … | 18 | 86 | … | … |

| Male | 51 | 9 | 42 | 0.89 (0.39–2.05) | .78 | 4 | 47 | 1.18 (0.33–4.23) | .80 | 12 | 39 | 1.47 (0.65–3.35) | .36 |

| Presentation | |||||||||||||

| Untreated or persistent (reference) | 110 | 10 | 100 | … | … | 4 | 106 | … | … | 5 | 105 | … | … |

| Recurrence | 45 | 21 | 24 | 8.75 (3.65–20.99) | <.001 | 7 | 38 | 4.88 (1.35–17.61) | .01 | 25 | 20 | 26.25 (8.98–76.73) | <.001 |

| Tumor size, cm | |||||||||||||

| ≤3 (reference) | 49 | 5 | 44 | … | … | 3 | 46 | … | … | … | 5 | 45 | … |

| >3 | 31 | 4 | 27 | 1.30 (0.32–5.28) | .71 | 2 | 29 | 1.06 (0.17–6.71) | .95 | 6 | 25 | 2.70 (0.70–10.48) | .15 |

| Unknown | 75 | 22 | 53 | … | … | 6 | 69 | … | … | 20 | 55 | … | … |

| T stage | |||||||||||||

| X | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 5 | ||||||

| 1 and 2 (reference) | 69 | 5 | 64 | … | … | 2 | 67 | … | … | 7 | 62 | … | … |

| 3 and 4 | 19 | 3 | 16 | 2.40 (0.51–11.11) | .26 | 2 | 17 | 3.94 (0.52–30.04) | .19 | 4 | 15 | 2.36 (0.61–9.13) | .21 |

| Unknown | 61 | 20 | 41 | … | … | 7 | 54 | … | … | 18 | 53 | … | … |

| N stage | |||||||||||||

| 0 (reference) | 115 | 17 | 98 | … | … | 5 | 110 | … | .19 | 96 | … | … | … |

| 1 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1.15 (0.13–10.49) | .90 | 0 | 6 | 1.55 (0.08–31.08) | .78 | 2 | 4 | 2.53 (0.43–14.79) | .30 |

| 2 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1.15 (0.13–10.49) | .90 | 0 | 6 | 1.55 (0.08–31.08) | .78 | 0 | 6 | 0.38 (0.02–7.04) | .52 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | … | … | 0 | 0 | … | … | 0 | 0 | … | … |

| Unknown | 28 | 12 | 16 | … | … | 6 | 22 | … | … | 9 | 19 | … | … |

| Parotidectomy | |||||||||||||

| Superficial (reference) | 72 | 13 | 59 | … | … | 6 | 66 | … | … | 10 | 62 | … | … |

| Partial enucleation | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2.27 (0.20–26.95) | .52 | 0 | 3 | 1.46 (0.07–31.05) | .81 | 0 | 3 | 0.85 (0.04–17.68) | .92 |

| Total | 58 | 13 | 45 | 1.31 (0.55–3.10) | .54 | 4 | 54 | 0.81 (0.22–3.05) | .76 | 12 | 46 | 1.62 (0.64–4.0) | .31 |

| Unknown | 22 | 4 | 18 | … | 1 | 21 | 8 | 14 | |||||

| Neck dissection | |||||||||||||

| No (reference) | 109 | 26 | 83 | … | … | 10 | 99 | … | … | 19 | 90 | … | … |

| Yes | 38 | 4 | 34 | 0.38 (0.12–1.16) | .09 | 1 | 37 | 0.27 (0.03–2.16) | .22 | 9 | 29 | 1.47 (0.60–3.60) | .40 |

| Unknown | 8 | 1 | 7 | … | … | 0 | 8 | … | … | 2 | 6 | … | … |

| Positive margins | |||||||||||||

| No (reference) | 63 | 10 | 53 | … | … | 5 | 58 | … | … | 11 | 52 | … | … |

| Yes | 71 | 9 | 62 | 0.77 (0.29–2.03) | .60 | 4 | 67 | 0.69 (0.18–2.70) | .60 | 11 | 60 | 0.87 (0.35–2.17) | .76 |

| Unknown | 21 | 12 | 9 | … | … | 2 | 19 | … | … | 8 | … | … | … |

| Radiation therapy | |||||||||||||

| No (reference) | 73 | 17 | 56 | … | … | 6 | 67 | … | … | 8 | 65 | … | … |

| Yes | 75 | 14 | 61 | 0.76 (0.34–1.67) | .49 | 5 | 69 | 0.69 (0.24–2.78) | .74 | 22 | 3.37 (1.39–8.19) | .01 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 0 | 7 | … | … | 0 | 7 | … | … | … | 0 | … | … |

Abbreviation: Ellipses indicate data not applicable.

With multimodality therapy, we observed a local control rate of 80%, with 31 patients developing a recurrence (Table 5). Prior recurrence was predictive of the development of another recurrence, and patients in this study with recurrent disease were 9-fold more likely to develop another local recurrence. The regional control rates were greater than 90%, with nodal failure occurring in only 11 patients (7.1%), and the presence of previous recurrence was predictive for additional regional recurrences (Table 5). Distant failure was observed in 30 patients (19.4%), most commonly in the lungs. In contrast to local and regional recurrences, distant recurrences were associated not only with previously recurrent disease but also age older than 45 years (Table 5). Furthermore, 13 patients (8.4%) died of their disease, with most of these deaths due to the development of distant metastases (76.9%, Table 4). The mean time to death from disease was 3.8 years (range, 0.7–11.2 years).

Discussion

Acinic cell carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that is generally classified as a low-grade salivary gland malignant neoplasm, with an estimated 5-year, disease-specific survival of more than 90%.5 Although most patients have a favorable prognosis, there is a small population who will ultimately succumb to their disease.5 Given the rarity of the disease, it remains difficult to identify which patients are at highest risk of death from their disease. Moreover, prior studies evaluating patients enrolled in regional and national tumor registries are complicated by nonstandardized treatment modalities. In the current study, we evaluated factors that were predictive of adverse outcomes among patients with ACC treated with a unified treatment strategy at a single institution.

In this study, we identified age as a critical predictor of outcome for ACC where older age is associated with decreased survival, which corroborates the findings of earlier studies.5 A novel discovery in the current study is that the decreased survival experienced by older patients appeared to be due to the development of distant metastases rather than age-related medical comorbidities. It has been reported that both increasing age and distant metastases are associated with increased risk of death from disease, but there has not been a previous link between age and the development of distant metastases.5

The sex preference toward females has been reported in prior studies, although the percentage of females affected in this series is slightly higher. Furthermore, females have not only a more favorable prognosis than males, with 10-year overall and disease-free survival rates of 80% and 42%, respectively, but also are less likely to die of their disease. Taken together, it appears female patients are more likely to be afflicted with ACC but have more favorable overall outcomes. The underlying biologic mechanisms for this phenomenon are not apparent.

Although most patients seen at our institution had presented with recurrent or persistent disease, no effect on overall survival was observed. However, disease-free survival was adversely affected among those patients with recurrent disease, and there was a higher likelihood of local-regional and distant metastasis. Not surprisingly, they were also more likely to die of their disease. Thus, these findings identify recurrent disease as a significant negative prognostic factor and emphasize the importance of appropriate initial management of ACC. This conclusion is supported by the outcomes of untreated or incompletely treated patients cared for at our institution, where only 11.8% developed a recurrence and resulted in only 2 disease-related deaths (1.7%).

As expected, patients with early-stage disease demonstrated improved survival and decreased risk of death from disease compared with patients with advanced-stage disease. Although clinical staging has prognostic value, only a small percentage of patients presented with stage III and IV disease. Alternatively, when we grouped lesions with a 3-cm cutoff, we observed a similar level of prognostic confidence, which may apply to broader groups of patients.

In this series, the extent of the surgical resection for this low-grade malignant neoplasm was likely biased toward a more comprehensive parotid dissection, with a large percentage of the patients presenting with recurrent disease necessitating a total parotidectomy (39.1%). Despite the aggressive management of the primary site in both recurrent and persistent cases, benefits in survival or local recurrence rates were not observed, which has been noted in other studies.9 Although cervical metastases are present in only approximately 10% of cases, the addition of a neck dissection appeared to decrease the rate of regional recurrences. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine which patients would benefit most from a neck dissection, but perhaps those with large tumors or those with high-grade features on preoperative biopsy warrant elective nodal dissection.

Traditionally, the addition of radiation therapy has been reserved for patients with recurrent disease, facial nerve involvement, high-grade histologic findings, regional disease, or positive surgical margins. Many of these high-risk features are extrapolated from the mucosal squamous cell carcinoma literature because of the rarity of salivary gland malignant neoplasms. In this series, 50.7% of patients received postoperative radiation, which is significantly higher than in previous reports.5,9 This finding most likely reflects the referral bias in our practice for recurrent and persistent disease. In our current experience, we observed no difference in the local and regional recurrence rates among patients treated with adjuvant radiation, which contradicts the findings of previous studies.13,14 We hypothesize that this finding is most likely due to the high rate of patients with persistent and recurrent dis ease represented in this series. Interestingly, this finding corroborates the study by Hoffman et al,5 in which patients receiving radiation therapy for ACC did not have improved recurrence rates and had a diminished overall survival.

We identified a group of patients with ACC of the salivary glands who are at high risk for the development of recurrences and death from their disease. In this study, we observed that male patients older than 45 years with lesions larger than 3 cm who have had a previous recurrence have adverse outcomes. Given the effect of recurrences on disease-specific survival, the appropriate initial management of ACC is crucial. Although the mainstay of treatment remains surgical excision, this study confirms that the extent of resection should be dictated by the disease, and more extensive procedures do not improve outcomes. Although we could not identify which patients would benefit from local intensification with adjuvant radiotherapy, we recommend it for patients with high-risk features, large tumors, and recurrent or persistent disease. Finally, although mortality is rare in patients with ACC, this series has identified that patients who die of their disease most frequently die of distant metastases. Currently, no chemotherapeutic agents have been approved for treatment of this disease, but our study suggests that there is a critical need for systemic therapeutic agents for ACC.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Kupferman had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Neskey, Bell, Kupferman. Acquisition of data: Neskey, Bell, Kies, Kupferman.

Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Neskey, Klein, Garden, Kupferman.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Bell, El-Naggar, Kies, Hicks, Weber, Kupferman.

Statistical analysis: Neskey, Klein, Hicks, Kupferman.

Administrative, technical, and material support: Kies, Kupferman.

Study supervision: El-Naggar, Weber, Kupferman.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Previous Presentation: This study was presented at the American Head and Neck Society 2013 Annual Meeting; April 11, 2013; Orlando, Florida.

Contributor Information

David M. Neskey, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Jonah D. Klein, School of Medicine, Temple University Medical School, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Stephanie Hicks, Department of Statistics, Rice University, Houston, Texas.

Adam S. Garden, Department of Radiation Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Diana M. Bell, Department of Pathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Adel K. El-Naggar, Department of Pathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Merrill S. Kies, Department of Thoracic Head and Neck Medical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Randal S. Weber, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Michael E. Kupferman, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

References

- 1.McHugh JB, Visscher DW, Barnes EL. Update on selected salivary gland neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(11):1763–1774. doi: 10.5858/133.11.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis GL, Auclair PL. Tumors of the Salivary Glands: Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2008. pp. 204–225. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Neyman N, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2009 (vintage 2009 populations) 2011 seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- 4.Hanna EYNSJ. Malignant tumors of the salivary gland. In: Myers ESJ, Myers J, Hanna E, editors. Cancer of the Head and Neck. 4th. Philadelphia, PA: WB Sanders; 2003. pp. 475–510. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Robinson RA, Pinkston JA, Menck HR. National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the head and neck. Head Neck. 1999;21(4):297–309. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199907)21:4<297::aid-hed2>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perzin KH, LiVolsi VA. Acinic cell carcinomas arising in salivary glands. Cancer. 1979;44(4):1434–1457. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197910)44:4<1434::aid-cncr2820440439>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batsakis JG, Luna MA, el-Naggar AK. Histopathologic grading of salivary gland neoplasms, II. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99(11):929–933. doi: 10.1177/000348949009901115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seifert G, Sobin LH. The World Health Organization’s Histological Classification of Salivary Gland Tumors. Cancer. 1992;70(2):379–385. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920715)70:2<379::aid-cncr2820700202>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiro RH, Huvos AG, Strong EW. Adenocarcinoma of salivary origin. Am J Surg. 1982;144(4):423–431. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz S, Zenk J, Müller M, et al. The many faces of acinic cell carcinomas of the salivary glands. Histopathology. 2012;61(3):395–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of Survival Data. London, England: Chapman and Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. 2nd. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu G, Hu Y, Jiang P, Qin D. The superiority of combined therapy (surgery and postoperative irradiation) in parotid cancer. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108(11):710–713. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1982.00790590032010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillamondegui OM. Salivary gland cancers, surgery, and irradiation therapy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108(11):709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]