Abstract

Background

Alcohol use among underage youth is a significant public health concern. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, alcohol is the “drug of choice” among adolescents, meaning more youth use and abuse alcohol than any other substance. Prevalence of alcohol use is disproportionately higher among sexual minority youth (SMY) than among their heterosexual peers. We examined sexual identity and sexual behavior disparities in alcohol use, and the mediational role of bullying in a sample of high school students.

Methods

Data from the 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey were used to assess the association between sexual minority status (identity and behavior) and alcohol use with weighted logistic regression. Due to well-documented differences between males and females, we stratified models by gender. Physical and cyberbullying were examined as mediators of the relationship between sexual minority status and alcohol use.

Results

We detected associations between certain subgroups of sexual minority youth and alcohol use across all four drinking variables (ever drank alcohol, age at first drink, current alcohol use, and binge drinking). Most of these associations were found among bisexual-identified youth and students with both male and female sexual partners; these individuals had up to twice the odds of engaging in alcohol use behaviors when compared with sexual majority students. Associations were strongest among females. Bullying mediated sexual minority status and alcohol use only among bisexual females.

Conclusions

As disparities in alcohol use differ by gender, sexual identity, and sexual behavior, interventions should be targeted accordingly.

Keywords: sexual minority youth, YRBS, bullying, alcohol

1.0 Introduction

Alcohol use among underage youth is a significant public health concern. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), alcohol is the “drug of choice” among adolescents, meaning more youth use and abuse alcohol than any other substance (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005). The 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) found that 63.2% of high school students in the United States reported drinking alcohol in their lives (Kann et al., 2016a). Nearly one-third (32.8%) had at least one drink in the thirty days prior to the survey, and 20.8% reported binge drinking during the same time period (Kann et al., 2016a). The 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reported lower, but still substantial proportions of people aged 12 to 20 years who had drunk alcohol in the prior month (22.8%), reported binge drinking (13.8%), and were classified as heavy drinkers (3.4%) (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015).

Deleterious health outcomes in youth are significantly associated with alcohol use. Individuals who initiate drinking prior to the age of 14 years are five times more likely to abuse alcohol or become dependent on alcohol later in their lives than those who start drinking at age 21 years or later (Hingson et al., 2006). Hingson et al. also found that the earlier the age of alcohol use initiation, the greater the likelihood that an individual will use other substances (Hingson et al., 2006). As brain development continues through the mid-20s, alcohol use in adolescence can have significant long-term effects on neurological functioning, including decreases in memory and cognition (Denoth et al., 2011). Further, alcohol use increases risk of depression (Armstrong and Costello, 2002), anxiety disorders (Armstrong and Costello, 2002), and attempting suicide (Wu et al., 2004), and negatively influences academic performance, which can seriously affect youths’ life trajectories. Underage drinking, particularly binge drinking, decreases the likelihood that youth will complete high school (DuPont et al., 2013) and is correlated with low grade point averages (Pascarella et al., 2007) and with missing classes (Wechsler et al., 1998).

Prevalence of alcohol use is disproportionately higher among sexual minority youth (SMY) than among their heterosexual peers (Kann et al., 2016b; Zaza et al., 2016). The Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), a cohort study of youths conducted between 1996 and 2003, found that SMY began drinking at earlier ages and had a greater risk of binge drinking than heterosexual youth (Corliss et al., 2008). A meta-analysis of studies of adolescent substance use found that lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth had 2.55 times the odds of recent alcohol use compared to heterosexual youth (Marshal et al., 2008). Additionally, pooled 2005 and 2007 YRBS data from 14 jurisdictions indicated SMY were more likely to report prior month drinking and heavy episodic drinking than their heterosexual counterparts (Talley et al., 2014).

Alcohol use differs not only by sexual orientation, but also by other demographic characteristics, including race, ethnicity, age, and sex. Data on 12–17 year olds from NSDUH found that past-year alcohol use varied widely from 37.0% of Native American adolescents to 2.5% of Asian/Pacific Islander adolescents (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015). In the 2015 National YRBS, current alcohol use was higher among White and Hispanic students (35.2% and 34.4%, respectively) than among Black students (23.8%) (Kann et al., 2016a). The prevalence of current alcohol use within the 2015 National YRBS also followed a linear trend by grade (9th grade: 23.4%; 10th grade: 29.0%; 11th grade: 38.0%; 12th grade: 42.4%). When looking exclusively at SMY, similar sex, race, and age differences have been found (Talley et al., 2014).

Victimization has been posited as potentially mediating the association between sexual minority youth and substance use. SMY report more serious and frequent experiences with harassment, particularly bullying, than their heterosexual peers, primarily due to contextual factors such as prejudice and social isolation (Kosciw et al., 2012). According to the 2015 National YRBS, 34.2% of LGB students reported past-year bullying on school property, compared to 18.8% of heterosexuals (Kann, 2016). Similarly, a meta-analysis of 26 North American school-based studies found that sexual minority adolescents were, on average, 1.7 times more likely than heterosexual peers to report assault by peers at school (Friedman et al., 2011). Furthermore, experiences of bullying are associated with alcohol use, especially among middle and high school students (Carlyle and Steinman, 2007; Nansel et al., 2004; Peleg-Oren et al., 2010; Radliff et al., 2012; Tharp-Taylor et al., 2009). A study of over 13,000 high school students in the Midwest found that a single-item assessing homophobic teasing was associated with alcohol use among all students, independent of sexual orientation; however, the association was strongest for sexual minority and “questioning” students (Espelage et al., 2008). Due to the clear interconnectedness of these factors, there is some empirical evidence for the role of victimization and bullying as a mediator. For instance, a study using Massachusetts and Vermont YRBS data from 1995 found that disparities in substance use across sexual orientation groups were partially explained by victimization in school (Bontempo and d’Augelli, 2002).

Additionally, the relationship between in-person, school-based bullying and cyberbullying has become increasingly relevant. While there is considerable overlap in who is victimized by these forms of bullying, recent studies have shown that electronic bullying and in-person bullying remain distinct experiences (Schneider et al., 2012). Cyberbullying has an aspect of perceived anonymity for its perpetrators, which results in deindividuation and reduced opportunities for sympathy and remorse (Kowalski et al., 2014; Postmes and Spears, 1998). Moreover, as young people become more increasingly accessible through online and mobile communications, perpetrators gain unbounded access to their victims, whereas school-based bullying is limited to interactions that occur during the school day (Kowalski et al., 2014). However, relationships between cyberbullying, gender, and sexuality remain under investigated. For example, some studies have shown that male adolescents often bully each other on the basis of perceived sexual minority status, and that there are gendered differences to perceptions of cyberbullying (Doucette, 2013; Notar et al., 2013). However, studies have been inconsistent or inconclusive on which genders or sexualities are more likely to experience victimization from cyberbullying (Erdur-Baker, 2010; Schneider et al., 2012). Thus, this study has the potential to fill the gap in the literature by examining relationships between school bullying and cyberbullying among SMY.

Methodological limitations in earlier studies have hampered researchers’ ability to determine the magnitude of sexual orientation disparities in alcohol use among youth, and to identify correlates of these disparities. In particular, research on alcohol use among SMY has primarily come from nonprobability samples (Institute of Medicine, 2011). While such studies have been crucial for identifying health issues, their developmental course, and risk and protective factors, such designs are less suited to describing health disparities. The primary limitation is the inability to ensure that SMY are drawn from non-biased populations comparable to non-SMY. Only recently have measures of sexual orientation been included within large national health surveillance systems (Institute of Medicine, 2011), such as the YRBS (Zaza et al., 2016), but these studies have been limited in the number of jurisdictions that assess sexual orientation status. The availability of information on sexual identity and sexual contact among youth within a national probability sample therefore provides an unprecedented ability to investigate disparities between SMY and heterosexual youth.

In the current study, we are using data from the 2015 National YRBS to examine the associations between four alcohol use variables and sexual minority status, measured both by reported sexual identity and sex of sexual contacts. This expands upon the previously cited work by including a nationally representative sample of high school students, investigating the differences between sexual minority definitions (identity vs. behavior), considering differences between sexual minority subgroups (e.g. gay vs. bisexual), and adding female youth to the study sample. Having a better understanding of the differences between sexual minority definitions and subgroups could be extremely beneficial for future research and interventions that may only focus on one aspect of sexuality. In addition, we assessed whether cyberbullying and in-school bullying mediate the association between sexual identity/contact and alcohol use.

2.0 Material And Methods

2.1 Sample

Data were gathered from high school students in the United States in 2015 as part of the National Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBSS) conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The 2015 National Survey utilized a 3-stage cluster design to generate a nationally representative sample of public and private school students in grades 9–12 in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (CDC et al., 2013; Kann et al., 2016a). Students in participating high schools completed self-report surveys assessing sexual identity, sexual contacts, demographic characteristics, and health-related behaviors and exposures. Surveys were completed by 15,624 youths across the United States.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Sexual Identity

Sexual identity was assessed by a question asking, “Which of the following best describes you?” Response options for this question were “Heterosexual (straight),” “Gay or lesbian,” “Bisexual,” and “Not sure.”

2.2.2 Sexual Contact

Sexual contact was measured by the question, “During your life, with whom have you had sexual contact?” Students could respond “I have never had sexual contact,” “Females,” “Males,” or “Females and males.” This variable was recoded by combining responses with the students’ reported sex. Students who reported only having sexual contact with individuals of a different sex were identified as “Different sex only”. Students who reported only having sexual contact with individuals of the same sex were coded as “Same sex only”. Finally, students who indicated having sexual contact with both males and females were coded as “Different and same sex.”

2.2.3 Bullying

Bullying was defined within the survey as “when 1 or more students tease, threaten, spread rumors about, hit, shove, or hurt another student over and over again. It is not bullying when 2 students of about the same strength or power argue or fight or tease each other in a friendly way.” In-school bullying was measured by the question, “During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied on school property?” Electronic bullying was measured by the question, “During the past 12 months, have you ever been electronically bullied? (Count being bullied through e-mail, chat rooms, instant messaging, websites, or texting.)”. For both questions, the response options were “Yes” or “No”.

2.2.4 Outcome Variables

2.2.4.1 Ever Drank Alcohol

Participants were asked, “During your life, on how many days have you had at least one drink of alcohol?” Responses were collapsed and dichotomized as “0 days” or “1 or more days,” replicating the categorization used by CDC (Kann et al., 2016a).

2.2.4.2 Age at First Drink

This variable was assessed by the question, “How old were you when you had your first drink of alcohol other than a few sips?” Potential response options were “I have never had a drink of alcohol other than a few sips,” “8 years old or younger,” “9 or 10 years old,” “11 or 12 years old,” “13 or 14 years old,” “15 or 16 years old,” and “17 years old or older.” The responses were collapsed and dichotomized as “Under 13 years old” and “At least 13 years old,” per the CDC dichotomization used with the 2015 YRBS national dataset (Kann et al., 2016a).

2.2.4.3 Current Alcohol Use

Participants were asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?” Responses were collapsed and dichotomized as “0 days” or “1 or more day” (Kann et al., 2016a).

2.2.4.4 Binge Drinking

Binge drinking was assessed by the question, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours?” Responses were collapsed and dichotomized as “0 days” or “1 or more days” (Kann et al., 2016a).

2.2.5 Demographics

2.2.5.1 Race/Ethnicity

Participants were asked if they identified as Hispanic or Latino. Additionally, participants could select all races that applied from the list of “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Asian,” “Black or African American,” “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander,” and “White.” Using CDC’s classification, these variables were combined into 8 racial/ethnic groups: (1) “American Indian or Alaska Native,” (2) “Asian,” (3) “Black or African American,” (4) “Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander,” (5) “White,” (6) “Hispanic/Latino,” (7) “Multiple – Hispanic,” and (8) “Multiple – Non-Hispanic” (Kann et al., 2016a).

2.2.5.2 Sex

Participants were asked to identify their sex with the item “What is your sex?” Response options were “Female” and “Male.”

2.2.5.3 Grade

Participants were asked, “In what grade are you?” Potential response options were “9th grade”, “10th grade”, “11th grade”, “12th grade”, and “Ungraded or other grade”. Students who selected “Ungraded or other grade” (n = 35) were dropped from analysis.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

In order to reach the final analytic sample, students were excluded if they were missing any of the primary demographic variables of interest (race/ethnicity: 2.3%; sex: 0.8%; grade: 0.8%; not mutually exclusive). The final overall analytic sample was 15,129 students, 96.8% of the original sample. For analyses examining sexual contact, students who had never had sexual contact (41.2%) were excluded (analytic sample = 7,913).

All data cleaning and recoding was conducted in SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Analyses were carried out using SAS-callable SUDAAN Version 11.0.1 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) to appropriately weight estimates and to account for the complex sampling design of YRBS. First, descriptive analyses were conducted. Unadjusted analyses were then performed to examine crude associations between alcohol use variables and sexual identity/sexual contact. Next, multivariable logistic models were used to estimate odds of each of the four outcomes (ever drank alcohol, age at first drink, currently alcohol use, and binge drinking) associated with sexual identity and sexual contact, after controlling for race/ethnicity, sex, and grade. Finally, sex-stratified multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the sex specific odds of each of the four outcome variables associated with sexual identity and sexual contacts, controlling for race/ethnicity and grade.

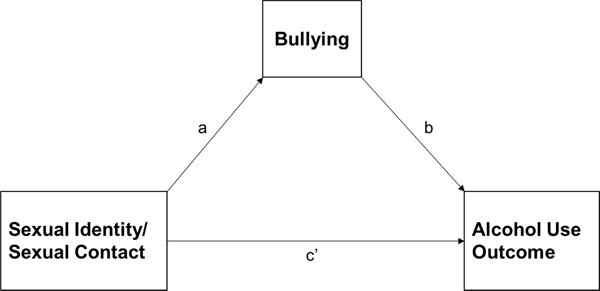

To assess the mediating effect of bullying on the association between sexual minority status and alcohol use outcomes, we used Mplus Version 7.31 (Figure 1). Path analysis and bootstrapping were used to estimate indirect effects. Bootstrapping was used to estimate appropriate standard errors for the path estimates and provide 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for the effects in the model (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Research shows that bootstrapping is one of the more valid and powerful methods for assessing mediating effects, and is preferred over traditional methods (Blashill, 2014; Hayes, 2009; Shrout and Bolger, 2002). Sex-stratified models were used to evaluate bullying as a mediator for the four outcome variables associated with sexual identity and sexual contacts, controlling for race/ethnicity and grade.

Figure 1.

Model for the Association between Sexual Identity/Sexual Contacts and Alcohol Outcomes, Mediated by Bullying.

3.0 Results

Nearly one-half of students within the analytic sample identified as male (51.0%), and nearly equal portions reported being within each of the four grade categories (Table 1). The sample was primarily comprised of non-Hispanic White students (54.6%), with 13.6% identifying as non-Hispanic Black or African American and 10.0% reporting being Hispanic and multiple races. The majority of students identified as heterosexual (91.8%), with 1.9% identifying as gay or lesbian, 6.0% identifying as bisexual, and 3.1% identifying as not sure. Similarly, 88.6% of sexually active students identified as having sexual contact with only individuals of a different sex, 2.9% of students only had sexual contact with individuals of the same sex, and 8.5% of students had sexual contact with both male and female individuals.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics (Unweighted and Weighted) of Students in the 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (N = 15,129).

| Unweighted | Weighted % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ||

| Age | |||

| 14 years old or younger | 1,668 | 11.3 | 10.2 |

| 15 years old | 3,716 | 24.6 | 26.2 |

| 16 years old | 3,927 | 25.9 | 25.1 |

| 17 years old | 3,745 | 25.8 | 23.7 |

| 18 years old or older | 2,062 | 13.6 | 14.9 |

| Grade | |||

| 9th grade | 3,901 | 25.8 | 27.2 |

| 10th grade | 3,843 | 25.4 | 25.7 |

| 11th grade | 3,850 | 25.5 | 23.8 |

| 12th grade | 3,535 | 23.4 | 23.2 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 7,599 | 50.2 | 49.0 |

| Male | 7,530 | 49.7 | 51.0 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 158 | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Asian | 625 | 4.1 | 3.8 |

| Black or African American | 1,651 | 10.9 | 13.6 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 94 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| White | 6,810 | 45.0 | 54.6 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2,348 | 15.5 | 10.0 |

| Multiple - Hispanic | 2,710 | 17.9 | 12.3 |

| Multiple - Non-Hispanic | 733 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| Electronic Bullied | |||

| Yes | 2,854 | 19.1 | 20.3 |

| No | 12,128 | 80.9 | 79.7 |

| School Bullied | |||

| Yes | 2,197 | 14.7 | 15.6 |

| No | 12,795 | 85.4 | 84.4 |

| Sexual Identity | |||

| Gay or Lesbian | 309 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| Bisexual | 889 | 6.2 | 6.0 |

| Not Sure | 466 | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| Heterosexual | 12,612 | 88.4 | 89.0 |

| Sexual Contact | |||

| Same Sex Only | 267 | 3.5 | 2.9 |

| Different and Same Sex | 702 | 9.1 | 8.5 |

| Different Sex Only | 6,769 | 87.5 | 88.6 |

3.1 Alcohol Use Characteristics

Nearly two-thirds of students reported having at least one drink of alcohol in their lives (63.5%); of those who had drunk alcohol, 27.9% were under the age of 13 years when they had their first alcoholic drink (Table 2). In terms of recent alcohol use, one-third of youths drank alcohol in the prior 30 days (33.0%), and 17.7% had at least 5 drinks in one sitting during the same time period. There were significant differences between all four alcohol use outcomes by both race/ethnicity and grade (p < 0.001; data not shown).

Table 2.

Alcohol Use Characteristics of Students in the 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, by Sex, Identity, and Contact.

| Ever drank alcohol | Age at first alcoholic drinkc | Drank alcohol, last 30 daysd | Binge drank, last 30 dayse | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | <13 years | ≥13 years | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| #a(%) | pb | #a(%) | pb | #a(%) | pb | #a(%) | pb | |||||

| Total | 9,408 (63.5) |

5,199 (36.6) |

2,715 (27.9) |

6,499 (72.1) |

4,532 (33.0) |

9,171 (67.0) |

2,641 (17.7) |

11,879 (82.3) |

||||

| Gender | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.365 | 0.119 | ||||||||

| Female | 4,915 (65.6) |

2,456 (34.4) |

1,188 (23.3) |

3,584 (76.7) |

2,374 (33.7) |

4,558 (66.3) |

1,289 (16.9) |

6,068 (83.1) |

||||

| Male | 4,493 (61.4) |

2,743 (38.6) |

1,527 (32.6) |

2,915 (67.4) |

2,158 (32.3) |

4,613 (67.8) |

1,352 (18.5) |

5,811 (81.5) |

||||

| Sexual Identity | <0.001 | 0.034 | 0.003 | 0.044 | ||||||||

| Gay or Lesbian | 200 (69.5) |

78 (30.5) |

70 (29.9) |

138 (70.1) |

87 (37.3) |

152 (62.3) |

59 (23.0) |

206 (77.0) |

||||

| Bisexual | 673 (77.6) |

184 (22.4) |

256 (33.8) |

412 (66.2) |

355 (41.9) |

427 (58.1) |

208 (21.4) |

640 (78.6) |

||||

| Not Sure | 275 (61.5) |

162 (38.5) |

96 (37.3) |

171 (62.7) |

135 (33.8) |

277 (66.2) |

71 (17.2) |

365 (82.8) |

||||

| Heterosexual | 7,839 (62.8) |

4,470 (37.2) |

2,163 (27.0) |

5,469 (73.0) |

3,733 (32.2) |

7,818 (67.8) |

2,176 (17.4) |

10,028 (82.6) |

||||

| Sexual Contact | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.010 | 0.233 | ||||||||

| Same Sex Only | 212 (80.3) |

51 (19.7) |

63 (27.6) |

137 (72.4) |

94 (41.5) |

129 (58.5) |

57 (23.9) |

186 (76.1) |

||||

| Different and Same Sex | 632 (88.7) |

70 (11.3) |

254 (40.0) |

359 (60.0) |

374 (57.4) |

237 (42.6) |

230 (31.4) |

431 (68.6) |

||||

| Different Sex Only | 5,385 (80.7) |

1278 (19.3) |

1,476 (25.9) |

3,828 (74.1) |

2,885 (48.3) |

3,163 (51.7) |

1,803 (27.5) |

4,643 (72.53) |

||||

Unweighted frequencies (#) are provided; percentages (%) reflect adjusted sampling weights

p-value for χ2 test of independence using weighted sample

Only asked of students who reported ever drinking alcohol

n=13,703

n=14,520

3.2 Bullying Characteristics

One-fifth (20.3%) of students reported being electronically bullied in the past year, and 15.6% of students reported being bullied on school property (Table 1). More female students than male students reported experiencing both forms of bullying (24.8% and 21.8%, respectively), and bisexual students were more likely to report being bullied than gay/lesbian students, students unsure of their sexual identity and heterosexual students (Table 3). Similarly, students who reported sexual contact with individuals of same and different sex reported the highest prevalence of bullying.

Table 3.

Bullying Characteristics of Students in the 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, by Sex, Sexual Identity, and Sexual Contact.

| Electronically Bullied | Bullied at School | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=2,854 | n=2,197 | |||

| #a(%) | pb | #a(%) | pb | |

| Sex | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 1690 (24.8) | 1500 (21.8) | ||

| Male | 1164 (15.9) | 697 (9.7) | ||

| Sexual Identity | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Gay or Lesbian | 81 (25.9) | 64 (19.5) | ||

| Bisexual | 312 (36.9) | 267 (30.6) | ||

| Not Sure | 117 (24.3) | 97 (21.0) | ||

| Heterosexual | 2182 (18.8) | 1636 (14.3) | ||

| Sexual Contact | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Same Sex Only | 74 (31.69) | 62 (25.4) | ||

| Different and Same Sex | 253 (35.1) | 234 (33.7) | ||

| Different Sex Only | 1295 (21.2) | 1096 (17.5) | ||

Unweighted frequencies (#) are provided; percentages (%) reflect adjusted sampling weights

p-value for χ2 test of independence using weighted sample

3.3 Alcohol Use and Sexual Minority Status

In unadjusted analyses, bisexual students were significantly more likely to report all four alcohol use activities than their heterosexual peers (Table 4). This association was observed for gay/lesbian youth compared to heterosexual youth only for lifetime alcohol use (OR = 1.35; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.79), and a borderline significant association was observed for recent binge drinking (OR = 1.42; 95% CI: 0.98, 2.05). Students not sure of their sexual identity were significantly more likely to report drinking before the age of 13 years than their heterosexual peers (OR= 1.61; 95% CI: 1.11, 2.34). For bisexual students, these associations persisted after controlling for race/ethnicity, grade, and sex; however, that was not the case for gay/lesbian youth. Similarly, students who reported sexual contact with both males and females were significantly more likely to engage in alcohol use behaviors than their peers who only had sexual contact with individuals of a different sex; this was observed in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. The sole exception was for recent binge drinking, in which the association was marginally insignificant (p = 0.06). For students who were unsure of their sexual identity, the association with age at first drink remained significant after controlling for race/ethnicity, grade and sex.

Table 4.

Alcohol Use Behaviors by Sexual Identity and Sex of Sexual Contacts, Stratified by Student Sex, in the 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

| Total | Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted** | ||

| OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Sexual Identity | ||||

| Ever Drank Alcohol | ||||

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.35 (1.03, 1.79) | 1.33 (0.99, 1.78) | 1.47 (0.83, 2.59) | 1.18 (0.71, 1.97) |

| Bisexual | 2.06 (1.59, 2.67) | 2.11 (1.59, 2.80) | 0.93 (0.61, 1.43) | 2.83 (1.93, 4.13) |

| Not Sure | 0.95 (0.67, 1.34) | 0.96 (0.69, 1.33) | 1.02 (0.65, 1.59) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.34) |

| Heterosexual | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) |

| Age at First Drink (<13 vs. 13+) | ||||

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.16 (0.77, 1.74) | 1.11 (0.73, 1.68) | 1.02 (0.56, 1.85) | 1.19 (0.61, 2.30) |

| Bisexual | 1.39 (1.08, 1.77) | 1.59 (1.18, 2.15) | 1.36 (0.71, 2.29) | 1.64 (1.19, 2.24) |

| Not Sure | 1.61 (1.11, 2.34) | 1.74 (1.20, 2.54) | 1.75 (0.86, 3.54) | 1.74 (1.26, 2.38) |

| Heterosexual | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) |

| Drank Alcohol, Last 30 Days | ||||

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.25 (0.89, 1.77) | 1.19 (0.84, 1.70) | 1.20 (0.59, 2.43) | 1.25 (0.78, 2.00) |

| Bisexual | 1.52 (1.20, 1.93) | 1.59 (1.25, 2.02) | 1.36 (0.87, 2.12) | 1.65 (1.21, 2.24) |

| Not Sure | 1.07 (0.80, 1.44) | 1.11 (0.70, 1.77) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.63) | |

| Heterosexual | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) |

| Binge Drank, Last 30 Days | ||||

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.42 (0.98, 2.05) | 1.49 (0.99, 2.24) | 1.38 (0.81, 2.34) | 1.63 (0.91, 2.89) |

| Bisexual | 1.30 (1.05, 1.60) | 1.45 (1.14, 1.85) | 1.60 (1.00, 2.59) | 1.40 (1.06, 1.86) |

| Not Sure | 0.99 (0.71, 1.37) | 1.05 (0.75, 1.46) | 1.02 (0.60, 1.73) | 1.06 (0.74, 1.50) |

| Heterosexual | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) |

| Sexual Contact | ||||

| Ever Drank Alcohol | ||||

| Same sex only | 0.95 (0.62, 1.47) | 1.03 (0.63, 1.71) | 0.92 (0.47, 1.82) | 1.08 (0.56, 2.07) |

| Same and different sex | 1.98 (1.40, 2.81) | 1.86 (1.27, 2.73) | 1.59 (0.81, 3.13) | 1.93 (1.27, 2.91) |

| Different sex only | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) |

| Age at First Drink (<13 vs. 13+) | ||||

| Same sex only | 1.09 (0.64, 1.94) | 1.06 (0.56, 2.02) | 0.47 (0.22, 1.03) | 1.50 (0.73, 3.06) |

| Same and different sex | 1.90 (1.43, 2.52) | 2.24 (1.64, 3.04) | 3.20 (1.69, 6.07) | 1.98 (1.40, 2.81) |

| Different sex only | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) |

| Drank Alcohol, Last 30 Days | ||||

| Same sex only | 0.76 (0.54, 1.08) | 0.84 (0.58, 1.22) | 0.69 (0.41, 1.16) | 0.89 (0.54, 1.86) |

| Same and different sex | 1.44 (1.10, 1.89) | 1.48 (1.12, 1.95) | 1.89 (1.08, 3.31) | 1.37 (1.00, 1.86) |

| Different sex only | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) |

| Binge Drank, Last 30 Days | ||||

| Same sex only | 0.83 (0.53, 1.28) | 1.01 (0.63, 1.63) | 0.73 (0.37, 1.43) | 1.18 (0.62, 2.25) |

| Same and different sex | 1.21 (0.97, 1.51) | 1.37 (1.06, 1.76) | 1.79 (1.03, 3.13) | 1.25 (0.95, 1.64) |

| Different sex only | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) | 1.00 (–) |

Controlling for race/ethnicity, grade, and gender.

Controlling for race/ethnicity and grade.

Bold: p<0.05; Italics: p<0.06

Similar, although less consistent, patterns emerged once the sample was stratified by sex. Among females, the positive association with alcohol use was found for both bisexual-identified and those who reported sexual contact with both male and female partners. The association with recent alcohol use approached statistical significance (p = 0.06), and recent binge drinking was not associated with sexual minority status. Females not sure of their sexual identity were significantly more likely to report drinking before the age of 13 years compared to their heterosexual peers. Among males, recent binge drinking was associated with both a bisexual identity and with reporting male and female sexual partners. Additionally, males who reported both male and female sexual partners were more than 3 times as likely to have taken their first alcoholic drink prior to the age of 13, compared to males with only different-sex partners. In contrast, males who only had same-sex partners were 53% less likely to have begun drinking before 13 years old, but this association was marginally insignificant (p = 0.06).

3.4 Mediating Effects of Bullying

There were no significant mediation effects for any of the outcomes within the male high school students (data not shown). In addition, there was no evidence for mediation for the alcohol use outcomes among females when looking at sexual contact (data not shown). Although there was no evidence for mediation effects when comparing lesbians or students not sure of their sexual identity with heterosexuals, we found evidence for mediation for the bisexual versus heterosexual comparison among females. Both electronic bullying and in-school bullying fully mediated the associated with lifetime, recent, and binge drinking (Table 5). The inclusion of electronic bullying partially mediated the association with age at first drink. However, there was not a significant indirect effect between in-school bullying and age at first drink.

Table 5.

Mediation Effects of Bullying on the Association between Sexual Identity and Alcohol Use Outcomes, Bisexual vs. Heterosexual Females in the 2015 National YRBS.

| Electronic Bullying | In-School Bullying | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | Beta | S.E.a | 95% CI value | p-value | Beta | S.E.a | 95% CI value | p-value |

| From Sexual Identity to Ever Drank | ||||||||

| Total effect | 0.606 | 0.105 | (0.405, 0.818) | <0.001 | 0.604 | 0.105 | (0.404, 0.816) | <0.001 |

| Indirect effect via bullying | 0.047 | 0.011 | (0.029, 0.070) | <0.001 | 0.059 | 0.015 | (0.032, 0.090) | <0.001 |

| Direct effect | 0.559 | 0.108 | (0.355, 0.776) | <0.001 | 0.545 | 0.103 | (0.350, 0.751) | <0.001 |

| From Sexual Identity to Age at First Drink (<13 vs 13+) | ||||||||

| Total effect | 0.300 | 0.094 | (0.130, 0.495) | 0.001 | 0.296 | 0.095 | (0.127, 0.492) | 0.002 |

| Indirect effect via bullying | 0.032 | 0.011 | (0.011, 0.056) | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.008 | (−0.001, 0.031) | 0.102 |

| Direct effect | 0.032 | 0.011 | (0.095, 0.466) | 0.005 | 0.283 | 0.096 | (0.111, 0.481) | 0.003 |

| From Sexual Identity to Drank Alcohol, Last 30 Days | ||||||||

| Total effect | 0.302 | 0.092 | (0.126, 0.484) | 0.001 | 0.301 | 0.092 | (0.124, 0.480) | 0.001 |

| Indirect effect via bullying | 0.043 | 0.009 | (0.027, 0.063) | <0.001 | 0.049 | 0.120 | (0.028, 0.074) | <0.001 |

| Direct effect | 0.260 | 0.094 | (0.077, 0.446) | 0.006 | 0.253 | 0.092 | (0.073, 0.432) | 0.006 |

| From Sexual Identity to Binge Drank, Last 30 Days | ||||||||

| Total effect | 0.197 | 0.078 | (0.037, 0.345) | 0.012 | 0.196 | 0.078 | (0.040, 0346) | 0.012 |

| Indirect effect via bullying | 0.041 | 0.011 | (0.023, 0.064) | <0.001 | 0.056 | 0.014 | (0.031, 0.085) | <0.001 |

| Direct effect | 0.156 | 0.08 | (−0.009, 0.307) | 0.053 | 0.139 | 0.081 | (−0.024, 0.294) | 0.084 |

Bootstrap derived standard errors (S.E.) and 95% confidence interval (CI); 10,000 bootstrap sample

4.0 Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, we detected clear associations between certain sexual minority subgroups and alcohol use across all four drinking variables. Nearly all were found among bisexual-identified youth and students with both male and female sexual partners; these sexual minority individuals had up to twice the odds of engaging in alcohol use behaviors when compared with sexual majority students. This is consistent with numerous prior studies that have found that bisexual individuals are disproportionately likely to use drugs and alcohol, even in comparison with gay and lesbian individuals (Drabble et al., 2013; Green and Feinstein, 2012; Hughes et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2014; Talley et al., 2016).

Research has begun to focus on explaining the potential drivers of disparities between bisexual and heterosexual youth, and between bisexual and gay/lesbian youth. For instance, higher rates of problematic substance use among bisexual individuals may be related to biphobia—bisexual-specific discrimination often perpetuated through microaggressions which stigmatize, question, erase, and ostracize bisexuals (Bostwick and Hequembourg, 2014; Green and Feinstein, 2012; Hequembourg and Brallier, 2009). Additionally, bisexuals tend to be at greater risk than either heterosexuals or gay/lesbian individuals for sexual, physical, and emotional victimization throughout their lives (Hughes et al., 2014). Because of the types of questions asked within YRBS, not all of these drivers of disparities could be assessed. Future work should explore these factors more deeply.

The heightened risk for alcohol outcomes observed in bisexual youth (versus heterosexuals and gay and lesbian youth) did not persist for other SMY. This finding contrasts the associations found in previous literature, which has been unable to disentangle subgroups of SMY in looking at alcohol use outcomes. In the overall sample, only recent binge drinking was significantly more common among gay/lesbian youth than heterosexual youth, and this association disappeared after controlling for demographic variables. One explanation for this lack of association may be the limited sample of SMY (only about 2% of students identified as gay or lesbian). Future research that pools 2015 local YRBS data across jurisdictions may be one way to test whether statistical power explains the lack of association. In 2015, 44 jurisdictions asked at least one of the sexual minority items in their local YRBS implementation (Kann et al., 2016b), resulting in a potential pooled dataset that is more than 14 times larger than the national YRBS dataset.

There were substantial differences between males and females in the prevalence of alcohol use behaviors, both in general and among sexual minority youth. Contrasting previous research that male and female adolescents tend to engage in similar levels of alcohol consumption (Johnston, 2010; Schulte et al., 2009), females were significantly more likely to have ever drunk alcohol, but had their first drink at an older age than male students. Similar results have been found between sexual minority men and women (Chow et al., 2013), but they have not been fully consistent (Bariola et al., 2016). Among sexual minority adolescents, 2005 and 2007 YRBS data found that females were heavier alcohol users than males (Talley et al., 2016). As the contradictory data from some of these studies are nearly a decade old, perhaps this reflects changing dynamics in alcohol initiation and usage among youths.

With regards to sexual minority status, bisexual females were significantly more likely to engage in all four alcohol use outcomes than their heterosexual peers, most clearly demonstrated by their nearly 3 times the odds of having ever drunk alcohol. This trend was only seen among bisexual males for recent binge drinking. Although it is unclear whether alcohol use is associated with identity itself or other latent factors not assessed within these analyses such as minority stress, our findings suggest that identifying as bisexual may be more strongly associated with alcohol use among females than males. Conversely, having sex with both male and female individuals was more strongly associated with alcohol use among males than among females, with the exception of having ever used alcohol. This may be explained by the findings that men more often describe substance use as a way to cope with stress, internalized stigma, and masculine insecurity related to sexual minority status (Hequembourg and Brallier, 2009). In the current study, there was also a striking difference between young men who only reported sexual contact with other men, and those who reported sexual contact with both males and females in terms of age at first drink; males who reported sexual contact with females and males were 3 times more likely to have initiated drinking before the age of 13, whereas males who reported sexual contact with only males were 50% less likely to have started drinking when they were 12 years old or younger. Although the latter association was marginally insignificant, it suggests that disparities are not consistent across sexual minorities. This may be explained by the lower social support and inclusion of bisexuals in sexual minority communities as a result of their engagement in heterosexual/romantic partnerships. (Bostwick and Hequembourg, 2014).

As hypothesized, we found evidence that bullying mediated the association between sexual minority status and alcohol use outcomes, but not for all subgroups. This association was limited to female youth, specifically comparing bisexual to heterosexual individuals. Thus, bisexual females are more likely to experience electronic and in-school bullying compared to their heterosexual female peers. Perhaps bisexual females experience more bullying due to biphobia. The bisexual females may have responded to their bullying experiences by using alcohol to cope with bisexual-specific discrimination (Green and Feinstein, 2012; Hequembourg and Brallier, 2009; Kosciw et al., 2012). Future research should continue to investigate the relationship between bullying and alcohol use in bisexuals, particularly among bisexual females.

This study has several limitations. First, these data are cross-sectional; thus there is no temporal order and causality cannot be established between the mediator bullying and alcohol use outcomes. Second, all data were assessed via self-report and may be affected by recall and social desirability bias. Self-report bias may be especially likely for bullying, which is often underreported (Bouris et al., 2016; Juvonen and Gross, 2008; Kosciw et al., 2012). Furthermore, YRBS only samples from schools and consequently excludes youth who are not enrolled or who may be less likely to attend school consistently due to substance use or fears of bullying. Therefore, our results might underestimate the prevalence and association between bullying and alcohol use. Third, when asking about sex of sexual contacts, YRBS does not specify consensual sexual contact. It is possible that youth who experienced childhood sexual abuse or sexual assault would include the perpetrator when reporting sex of sexual contact, thus conflating two very different types of sexual contact within one variable. Finally, although we used a large nationally representative sample, only a small portion of the students identified as SMY. Small sample sizes make it difficult to detect uncommon phenomena, especially after including additional covariates.

5.0 Conclusions

This research improves some methodological limitations of prior alcohol research among SMY. In much previous research, all sexual minorities are combined in one group due to small sample sizes (Bouris et al., 2016; Espelage et al., 2008; Hughes et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2014; Skerrett et al., 2016). By using a large, nationally representative sample, we were able to investigate the relationship between specific subgroups of SMY and alcohol use. This study also explored the differential associations in alcohol use by identity and behavior; we found that this distinction had a clear impact on findings, a nuance that may have been missed if these were collapsed into a single measure of sexual minority status, as has been done in many other studies (Blashill and Safren, 2014; Bostwick et al., 2014; Bouris et al., 2016). Finally, we were able to demonstrate clear differences in alcohol use by sex. Thus, while the results of this study align with previous literature in showing associations between alcohol use and SMY, our results differ from that literature in that we were able to show that these associations may exist for some groups of SMY (namely bisexual-identified female youth) but not others. Our findings suggest the need for alcohol cessation interventions for SMY to be preferentially targeted to female youth who identify as bisexual. Few interventions focused on substance/alcohol use have been specifically developed for SMY, let alone targeting specific SMY subgroups (Schwinn et al., 2015). Some investigations point to the potential role of gay-straight alliances (GSAs) in schools as a source of support for SMY, thereby reducing risk for alcohol and substance misuse (Heck et al., 2014; Ioverno et al., 2016). Thus, GSAs may serve as an ideal location for developing supportive alcohol cessation interventions for bisexual female youth.

Highlights.

Bisexual youth had twice the odds of alcohol use compared to sexual majority youth.

Bullying mediated sexual minority status’ association with alcohol use in females.

Alcohol disparities between males and females regardless of sexual identity existed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their role in developing the YRBSS.

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA024409).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures

Contributors

GP developed the research questions and drafted all sections of the manuscript. BT conducted all analyses and created tables and figures. PS drafted the introduction and reviewed the entire manuscript. MB reviewed and edited the entire manuscript. MLH reviewed and edited the entire manuscript. MN reviewed and edited the entire manuscript. RM edited the entire manuscript and assisted with table development. BM reviewed and edited the entire manuscript. All authors approved of the final manuscript before submission.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariola E, Lyons A, Leonard W. Gender-specific health implications of minority stress among lesbians and gay men. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40:506–512. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ. A dual pathway model of steroid use among adolescent boys: Results from a nationally representative sample. Psychol Men Masculin. 2014;15:229. doi: 10.1037/a0032914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Safren SA. Sexual orientation and anabolic-androgenic steroids in US adolescent boys. Pediatrics. 2014;133:469–475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, d’Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:364–374. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick W, Hequembourg A. ‘Just a little hint’: bisexual-specific microaggressions and their connection to epistemic injustices. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16:488–503. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.889754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Meyer I, Aranda F, Russell S, Hughes T, Birkett M, Mustanski B. Mental health and suicidality among racially/ethnically diverse sexual minority youths. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouris A, Everett BG, Heath RD, Elsaesser CE, Neilands TB. Effects of victimization and violence on suicidal ideation and behaviors among sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. LGBT Health. 2016;3:153–161. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle KE, Steinman KJ. Demographic differences in the prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of adolescent bullying at school. J School Health. 2007;77:623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, Kinchen S, Eaton DK, Hawkins J, Flint KH, Centers for Disease, C., Prevention methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system–2013. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality, C.f.B.H.S.a., editor. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2015. (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50). [Google Scholar]

- Chow C, Vallance K, Stockwell T, Macdonald S, Martin G, Ivsins A, Marsh DC, Michelow W, Roth E, Duff C. Sexual identity and drug use harm among high-risk, active substance users. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15:311–326. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.754054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin SB. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents findings from the growing up today study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoth F, Siciliano V, Iozzo P, Fortunato L, Molinaro S. The association between overweight and illegal drug consumption in adolescents: Is there an underlying influence of the sociocultural environment? PLoS One. 2011;6:e27358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette JD. Gender And Grade Differences In How High School Students Experience And Perceive Cyberbullying. The University of Western Ontario; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, Lown AE. Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27:639. doi: 10.1037/a0031486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPont RL, Caldeira KM, DuPont HS, Vincent KB, Shea CL, Arria AM. American’s Dropout Crisis: The Unrecognized Connection To Adolescent Substance Use. Institute for Behavior and Health, Inc.; Rockville, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Erdur-Baker Ö. Cyberbullying and its correlation to traditional bullying, gender and frequent and risky usage of internet-mediated communication tools. New Media Society. 2010;12:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Aragon SR, Birkett M, Koenig BW. Homophobic teasing, psychological outcomes, and sexual orientation among high school students: What influence do parents and schools have? School Psychol Rev. 2008;37:202. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, Wei C, Wong CF, Saewyc EM, Stall R. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1481–1494. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KE, Feinstein BA. Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: An update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:265. doi: 10.1037/a0025424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Comm Monographs. 2009;76:408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Livingston NA, Flentje A, Oost K, Stewart BT, Cochran BN. Reducing risk for illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse: High school gay-straight alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Addict Behav. 2014;39:824–828. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg AL, Brallier SA. An exploration of sexual minority stress across the lines of gender and sexual identity. J Homosex. 2009;56:273–298. doi: 10.1080/00918360902728517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010;105:2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Steffen AD, Wilsnack SC, Everett B. Lifetime victimization, hazardous drinking, and depression among heterosexual and sexual minority women. LGBT Health. 2014;1:192–203. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioverno S, Belser AB, Baiocco R, Grossman AH, Russell ST. The protective role of gay–straight alliances for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning students: A prospective analysis. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2016;3:397. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. Monitoring the future: National results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. DIANE Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Gross EF. Extending the school grounds?—Bullying experiences in cyberspace. J School Health. 2008;78:496–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L. Sexual Identity, Sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12—United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Queen B, Lowry R, Olsen EO, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Yamakawa Y, Brener N, Zaza S. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016a;65:1–174. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Yamakawa Y, Brener N, Zaza S. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12 - United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016b;65:1–202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA. The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. ERIC. GLSEN; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1073–137. doi: 10.1037/a0035618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, Bukstein OG, Morse JQ. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, Saluja G, Ruan WJ. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:730–736. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The Scope of the Problem 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Notar CE, Padgett S, Roden J. Cyberbullying: A review of the literature. Universal J Edu Res. 2013;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella ET, Goodman KM, Seifert TA, Tagliapietra-Nicoli G, Park S, Whitt EJ. College student binge drinking and academic achievement: A longitudinal replication and extension. J Coll Student Dev. 2007;48:715–727. [Google Scholar]

- Peleg-Oren N, Cardenas GA, Comerford M, Galea S. An association between bullying behaviors and alcohol use among middle school students. J Early Adolesc. 2010;32:761–775. 0272431610387144. [Google Scholar]

- Postmes T, Spears R. Deindividuation and antinormative behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1998;123:238. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Method. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radliff KM, Wheaton JE, Robinson K, Morris J. Illuminating the relationship between bullying and substance use among middle and high school youth. Addict Behav. 2012;37:569–572. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SK, O’donnell L, Stueve A, Coulter RW. Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: A regional census of high school students. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:171–177. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte MT, Ramo D, Brown SA. Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwinn TM, Thom B, Schinke SP, Hopkins J. Preventing drug use among sexual-minority youths: Findings from a tailored, web-based intervention. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:571–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol Method. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerrett DM, Kõlves K, De Leo D. Factors related to suicide in LGBT populations. Crisis. 2016;37:361–9. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Gilbert PA, Mitchell J, Goldbach J, Marshall BD, Kaysen D. Addressing gaps on risk and resilience factors for alcohol use outcomes in sexual and gender minority populations. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35:484–93. doi: 10.1111/dar.12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Hughes TL, Aranda F, Birkett M, Marshal MP. Exploring alcohol-use behaviors among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents: Intersections with sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:295–303. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, D’Amico EJ. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addict Behav. 2009;34:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Changes in binge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and 1997. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. J Am Coll Health. 1998;47:57–68. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Hoven CW, Liu X, Cohen P, Fuller CJ, Shaffer D. Substance use, suicidal ideation and attempts in children and adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34:408–420. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.4.408.53733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaza S, Kann L, Barrios LC. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: Population estimate and prevalence of health behaviors. JAMA. 2016;316:2355–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]