Abstract

A narrative synthesis was conducted to determine typical patient- and family-centered care (PFCC) components and their link to outcomes in pediatric populations. 68 studies with PFCC interventions and experimental designs were included. Study features were synthesized based on five core PFCC components (i.e., education from the provider to the patient and/or family, information sharing from the family to the provider, social-emotional support, adapting care to match family background, and/or shared decision-making) and four outcome categories (health status; the experience, knowledge, and attitudes of the patient/family; patient/family behavior; or provider behavior). The most common PFCC component was education; the least common was adapting care to family background. The presence of social-emotional support alone, as well as educational interventions augmented with shared decision making, social-emotional support, or adaptations of care based on family background, predicted improvements in families' knowledge, attitudes, and experience. Interventions that targeted the family were associated with positive outcomes.

Keywords: Patient- and family-centered care, Shared decision-making

Introduction

Since the landmark report from the Institute of Medicine on Crossing the Quality Chasm,1 attention to patient- and family-centered care (PFCC), with the goal of increasing partnerships among providers, families, and patients, has been prioritized as a core component of quality health care. Prior to that report, the Institute of Patient- and Family-Centered Care was founded as a nonprofit organization in 1992 (previously the Institute for Family-Centered Care), introducing more widely the concept of patient- and family-centered care (PFCC).2-4 A recent policy statement in Pediatrics5 outlined six core principles of patient- and family-centered care: (1) listening to and respecting the child and family while honoring and incorporating family background into health care planning and delivery; (2) ensuring sufficient flexibility on organizational, procedural, and provider levels to tailor services to families' needs, beliefs, and values; (3) open and ongoing information-sharing from provider to family; (4) formal and informal support for the patient and family; (5) collaboration between providers, patients, and families at all levels of health care; and (6) building on patients' and families' strengths to empower them to participate in decision-making. A major goal of PFCC in pediatric health care and mental health care settings is to change the family's role in their child's health care—to being crucial and equal participants in their child's health care. Despite this overarching goal, the best methods to implement PFCC remain elusive, in part due to the dearth of evidence supporting its efficacy in pediatric health.6, 7

Calls for PFCC are also occurring outside of pediatric health care. In one prominent example, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) described the six dimensions of quality in health care as safety, efficiency, effectiveness, equity, timeliness and patient-centeredness (with patient-centered defined as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions”).1 The goals of PFCC are also in line with the “Triple Aim” framework created by Donald Berwick and colleagues at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI): that new initiatives should improve the individual experience of health care (including quality and satisfaction), improve the health of populations, and decrease the per capita cost of care.8 The first tenet of the Triple Aim, improving the individual experience of health care, is in line with the principles of PFCC in health care settings.

Despite calls for increased presence of PFCC in pediatric health care settings,5 challenges remain—challenges that can often be attributed to a tendency for providers to focus on diagnosing and managing diseases. By involving families in making decisions, supporting their needs, and adapting care to fit their backgrounds, providers can ensure that families are more effective participants in their children's care. However, the concept of PFCC remains broad, and different stakeholders have emphasized different aspects of PFCC. Without a clear understanding of which components of PFCC are most effective, establishing clear standards of care is elusive. A better understanding of which components of PFCC lead to positive outcomes can allow for more targeted development of effective interventions.

Recent adult studies demonstrated that including PFCC components positively affected patients' and families' experience of care; in addition to patients' subjective experience of their care, PFCC has been linked to various types of outcomes related to patient behavior (e.g., clinical adherence9-11 and decreased readmissions12, 13) as well as health status, such as reduced rates of mortality.14 A Cochrane review of PFCC trainings for providers who conduct clinical consultations found that PFCC trainings were effective in supporting providers to share control of topics and decisions with patients, with mixed findings on resulting levels of patient satisfaction, general health, and health behaviors.15 In the pediatric literature, two recent Cochrane reviews of family-centered care for hospitalized children found zero7 and one6 acceptable study, respectively, that met rigorous inclusion criteria, underscoring the lack of high-quality quantitative research on PFCC. Some evidence for the benefit of PFCC in pediatric setting was found, especially on clinical care, parental satisfaction and costs, but the authors cautioned about the preliminary nature of these conclusions given the small sample size.6 A Cochrane Review of qualitative studies in the pediatric literature found that negotiation (a concept which is similar to shared decision-making) between pediatric patients and/or parents and providers was associated with more successful interactions during a child's hospitalization.16

In recent years, growing evidence of the importance of including family members in a child's health care experience has led to an increased focus on PFCC in pediatric health care settings. The goal of this paper is to review the current state of the evidence in the pediatric literature on PFCC. Our objectives were to review all studies that assessed the impact of PFCC interventions across pediatric health conditions, to identify core components of this broadly defined concept across these studies, and to examine which components of PFCC are associated with specific outcomes.

Methods

Study Eligibility Criteria

Given the relative dearth of eligible studies of PFCC in pediatric populations found in the recent Cochrane reviews,6, 7 we utilized a narrative synthesis approach to review and synthesize the findings from multiple studies, focusing on qualitative descriptions of outcomes and methods.We reviewed the literature to identify specific components of PFCC that have been used in experimental studies through a comprehensive review of the previous decade and a half of literature (from 1998-2013). We first developed a taxonomy to classify the core PFCC components specific to pediatric populations; we focused on studies that primarily included patients age 0-12 in our review because of the shift in both child and parental roles in adolescents' care. To qualify as a PFCC intervention for this review, an intervention must have been identified by the authors as being patient-centered, family-centered or involving shared decision making, considered a hallmark of patient-centered care (Dwamena et al., 2012) (Table 1). We excluded several studies that described PFCC as simply allowing a parent to be present during a child's procedure, or making structural improvements to a family waiting area, because they did not sufficiently meet the criteria of more current definitions of PFCC in the literature. While PFCC can occur at different levels,17 this paper focuses on the direct care (i.e., patient and provider) level.

Table 1. Search methods.

| Search Field | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| SET 1: Topic | |

| Abstract/Title | “patient centered” OR |

| “patient centred” OR | |

| “patient-centeredness” OR | |

| “patient-centredness” OR | |

| “family centered” OR | |

| “family centred” OR | |

| “family-centeredness” OR | |

| “family-centredness” OR | |

| “shared decision-making” | |

| SET 2: Population | |

| Abstract/Title | child* OR |

| adolescent* OR | |

| family OR | |

| pediatric* OR | |

| paediatric* | |

| SET 3: Methods | |

| All Text | treatment OR |

| intervention OR | |

| “randomized controlled trial” OR | |

| “randomised controlled trial” OR | |

| RCT | |

The PubMed database was searched with Set 1 AND Set 2 AND Set 3 of search terms.

Additional Filters: Journal Articles, Published 1998-2013, English Language

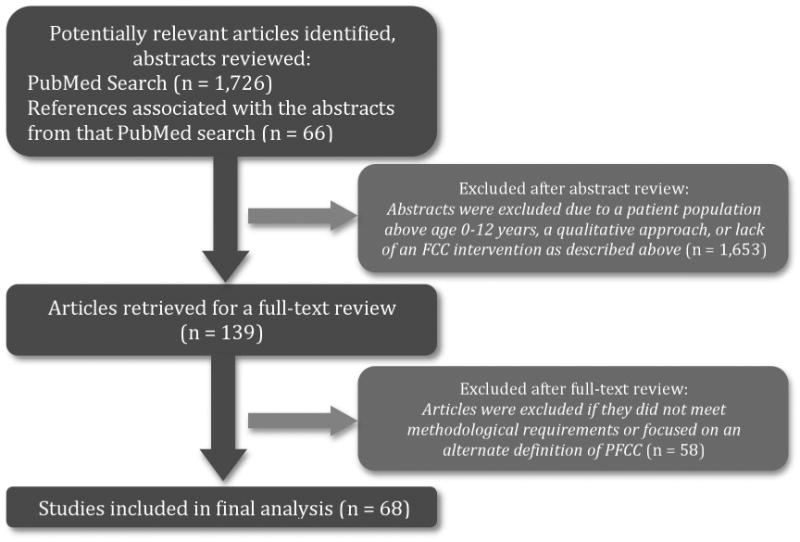

Only studies with experimental designs were included. (See Figure 1 for the article selection process; search terms are listed in Table 1.) The PubMed search, which focused on studies published between 1998 and 2013, resulted in the identification of 1,792 studies. All abstracts were reviewed by the lead author (KG) to select articles that merited a full-text review; 135 met criteria for a full-text review. Criteria for full-text review were: (1) experimental design; (2) at least one outcome category reported; (3) at least one category of PFCC included (i.e., education from the provider to the patient and/or family (Edu), information sharing from the family to the provider (InfoShare), social-emotional support (SocEm), adapting care to match the family background, (Adapt), and/or shared decision-making (SDM). To ensure the comprehensiveness of our study, we further cross-referenced our selected articles with the Cochrane Reviews by Shields et al. (2007 and 2012) and reviewed additional relevant studies referenced in the 135 articles selected, bringing the total number of abstracts to 139. Two independent coders (KG, LH) reviewed the full-text articles to determine if each article met final inclusion criteria. In the event of a discrepancy, or if inclusion was unclear, coders conferred with each other and the senior author (SO) to make a final determination. From the 139 papers reviewed, 81 articles comprising 68 distinct studies met final inclusion criteria. Studies that examined the same study population were linked in our analyses. See Table 3 for information about included studies' design, setting, and population.

Figure 1. Study Selection Process.

Table 3. Included studies and study characteristics.

| Study # | Authors | Setting | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (1) Als et al., 2003; (2) McAnulty et al., 2009 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 2 | McAnulty et al., 2010 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 3 | Als et al., 2004 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 4 | Arauz Boudreau et al., 2013 | Outpatient | Obesity |

| 5 | Barkin et al., 2012 | Outpatient | Obesity |

| 6 | Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011 | Outpatient | Infants at high risk of developmental disorders |

| 7 | Brinkman et al., 2013 | Outpatient | ADHD |

| 8 | Chan et al., 2002 | Inpatient | Post-Anesthesia Care Unit |

| 9 | Cooper et al., 2007 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 10 | Goldbeck et al., 2001 | Outpatient | Cystic fibrosis |

| 11 | Ireys et al., 2001 | Outpatient | Chronic illness |

| 12 | Junnila et al., 2012 | Outpatient | Mildly overweight children |

| 13 | Kamerling et al., 2008 | Inpatient | Post-Anesthesia Care Unit |

| 14 | Kleberg et al., 2000 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 15 | Kressin et al., 2009 | Outpatient | Risk of tooth decay |

| 16 | Kuo et al., 2012 | Inpatient | General pediatric inpatient |

| 17 | (1)Maguire et al., 2009; (2)Maguire et al., 2009 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 18 | McCann et al., 2008 | Inpatient | Medical and surgical wards |

| 19 | McKean et al., 2012 | Outpatient | Speech disorders |

| 20 | Mello et al., 2004 | Inpatient | PICU |

| 21 | Melnyk et al., 2006 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 22 | Melnyk et al., 2004 | Inpatient | PICU |

| 23 | Melnyk et al., 2001 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 24 | Morey et al., 2012 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 25 | O'Brien et al., 2013 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 26 | Penticuff et al., 2005 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 27 | Porter et al., 2006 | Inpatient | Asthma or other respiratory complaint |

| 28 | Preyde et al., 2003 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 29 | Samadi et al., 2013 | Outpatient | Autism |

| 30 | (1)Skuladottir et al., 2003 (2)Thome et al., 2005 | Inpatient | Sleep problems |

| 31 | Tzeng et al., 2010 | Outpatient | Asthma |

| 32 | (1)van der Pal et al., 2007; (2)van der Pal et al., 2007 (3)van der Pal et al., 2008 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 33 | Voos et al., 2011 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 34 | Wade et al., 2006 | Outpatient | Traumatic Brain Injury |

| 35 | Weis et al., 2013 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 36 | Westermann et al., 2013 | Outpatient | Mental health |

| 37 | (1)Westrup et al., 2000; (2)Kleberg et al., 2002; (3)Westrup et al., 2002; (4)Westrup et al., 2004; (5)Kleberg et al., 2007 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 38 | (1)Wielenga et al, 2006.; (2)Wielenga et al., 2007; (3)Wielenga et al., 2009 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 39 | Won, 2006 | Inpatient | Procedures requiring intravenous procedures |

| 40 | Woods et al., 2012 | Outpatient | Acquired Brain Injury |

| 41 | Wright et al., 2013 | Outpatient | Obesity risk |

| 42 | Borhani et al., 2011 | Outpatient | Thalassemia |

| 43 | Bouvé et al., 1999 | Inpatient | PICU |

| 44 | Brady et al., 2013 | Inpatient | Acute osteomyelitis |

| 45 | Clark et al., 2000 | Outpatient | Asthma |

| 46 | Davison et al., 2013 | Outpatient | Obesity |

| 47 | Dudas et al., 2010 | Inpatient | General pediatric inpatient |

| 48 | Byers et al., 2006 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 49 | Felder-Puig et al., 2003 | Inpatient | Ear, nose, and throat surgery |

| 50 | Gray et al., 2000 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 51 | Hughes et al., 2008 | Outpatient | Overweight |

| 52 | Stewart et al., 2006 | Outpatient | Special needs |

| 53 | (1)Kain et al., 2007; (2)Fortier et al., 2011 | Inpatient | Elective surgery |

| 54 | Lammi & Law, 2003 | Outpatient | Cerebral palsy |

| 55 | Peters et al., 2009 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 56 | Hart et al., 2006 | Outpatient | General ambulatory care |

| 57 | Kuntaros et al., 2003 | Inpatient | PICU |

| 58 | Monzavi et al., 2006 | Outpatient | Overweight |

| 59 | Clark et al., 1998 | Outpatient | Asthma |

| 60 | van Dulmen & Holl, 2000 | Outpatient | Unspecified |

| 61 | Porter et al., 2005 | Inpatient | Asthma |

| 62 | Porter et al., 2008 | Inpatient | Emergency room |

| 63 | Cho et al., 2012 | Outpatient | Preterm infants |

| 64 | Welch et al., 2013 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 65 | (1)Als et al., 2011; (2)McAnulty et al., 2013 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 66 | Als et al., 2012 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 67 | Kleberg et al., 2008 | Inpatient | NICU |

| 68 | Ullenhag et al., 2009 | Inpatient | NICU |

PFCC Core Components and Coding Process

Following an initial review of the existing definitions of PFCC and the studies included in this review, three study authors independently generated components of PFCC. Through an iterative process and by consensus, we distilled descriptions of PFCC interventions into five distinct components: (1) education from the provider to the patient and/or family (Edu), (2) information sharing from the family to the provider (InfoShare), (3) social-emotional support (SocEm), (4) adapting care to match the family background, (Adapt), and/or (5) shared decision-making (SDM) (see Table 2 for components and explanations). Further, we focused on four categories of commonly examined outcomes, namely, the experience, knowledge, and attitudes of the patient or family; patient or family behavior; provider behavior; or health status.

Table 2. Components of Patient- and Family-Centered Care.

| Component | Abbreviation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Education from the provider to the patient and/or family | Edu | Information given by the provider to the patient and/or family about any relevant topic (e.g., causes of the disease, treatment options, possible health status). |

| Information sharing from family to provider | InfoShare | Factual exchanges of information by the patient and/or family to the provider that do not involve negotiation and decision-making. |

| Social-emotional support | SocEm | Formal and informal emotional support5 given directly or indirectly (e.g., through support groups or networking opportunities with other families) by the provider to the patient or family to support self-efficacy, increase confidence, reduce anxiety, etc. |

| Adapting care to match the family background | Adapt | Eliciting of patient and/or family preferences and needs so that care can be adapted to be consistent with and respectful of them (including but not limited to racial, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic background, and patient and family experiences). |

| Shared decision-making | SDM | A collaborative process which allows patients and families access to the information needed to help them participate in care (possibly requiring that information be presented in a range of cultural and linguistic formats); this information includes all care options and their potential benefits and risks/harms. SDM involves a negotiation or discussion between family and provider about care that takes into account best available scientific evidence and family/patient preferences and values.21 |

Once article selection was finalized, each article was coded according to the above set of variables. In addition, we also examined the effects of targeting different participants in children's health care (i.e., provider only, patient and/or family only, or both). Most studies examined impact of PFCC on more than one outcome or used multiple metrics within each outcome. Because studies are not consistent in identifying primary versus secondary outcomes, and we did not attempt to distinguish these in our exploratory study. Rather, we took a blunt approach to examine the effects of the intervention on each outcome category, assigning each intervention's impact on each outcome category as positive/improved, negative/worsened, or no change/neutral. Where multiple metrics were used under each outcome category, we assigned impact based on the majority of findings related to that outcome category. A primary coder was assigned to each article, and a secondary coder check coded 20% of the primary coder's work (κ = .833, p < .001). Disagreements were resolved through discussion among all the authors.

To explore potential links between PFCC components and outcomes, descriptive statistics (Chi-square) were utilized to examine whether PFCC components (number and specific components) or the intended target of the care component were associated with outcomes. We utilized regression analyses to determine whether the target of a study's intervention (i.e., the provider, the patient and/or family, or both) had an effect on the percentage of positive outcomes. (Reported means and standard deviations are for the percentage of positive results).

See table 4 for comprehensive ratings from each study. As these are exploratory analyses, we did not correct for multiple tests.

Table 4.

PFCC components and outcomes by study.

| PFCC Component | Target of the Intervention | Outcomes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study # | Info Share | SocEm | Adapt | SDM | Edu | Provider | Patient/Family | Provider Behavior | Patient/ Family Behavior | Health status | Patient/ Family Experience, Knowledge, Attitudes |

| 1 | X | X | X | X | ● | ● | |||||

| 2 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ||||||

| 3 | X | X | X | X | ● | ||||||

| 4 | X | X | X | ◐ | ◐ | ||||||

| 5 | X | X | X | ● | |||||||

| 6 | X | X | ◐ | ||||||||

| 7 | X | X | X | X | X | ● | |||||

| 8 | X | X | ● | ||||||||

| 9 | X | X | X | X | X | ● | ● | ||||

| 10 | X | X | ○ and ● | ○ | |||||||

| 11 | X | X | X | ● | |||||||

| 12 | X | X | X | ○ and ◐ | |||||||

| 13 | X | ● | |||||||||

| 14 | X | X | X | ● | ● | ||||||

| 15 | X | X | ● | ● | |||||||

| 16 | X | X | ● | ◐ | ● | ||||||

| 17 | X | X | X | ◐ | |||||||

| 18 | X | X | ● | ◐ | ◐ | ||||||

| 19 | X | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ◐ | ||||

| 20 | X | X | X | ○ | ◐ | ||||||

| 21 | X | X | ● | ● | ◐ | ||||||

| 22 | X | X | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| 23 | X | X | ● | ◐ | |||||||

| 24 | X | X | ● | ||||||||

| 25 | X | X | X | X | ● | ◐ | ● | ||||

| 26 | X | X | X | X | ● | ● | |||||

| 27 | X | X | ◐ and | ◐ and ○ | |||||||

| 28 | X | X | ◐ | ● | |||||||

| 29 | X | X | X | ● | ● | ||||||

| 30 | X | X | X | ● | ● | ||||||

| 31 | X | X | X | ● | ● | ||||||

| 32 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ◐ | |||||

| 33 | X | X | X | ● | ◐ | ||||||

| 34 | X | X | X | X | ● | ● | |||||

| 35 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ◐ | |||||

| 36 | X | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ● | ● | |||

| 37 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ◐ | |||||

| 38 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ◐ | |||||

| 39 | X | X | ● | ● and ◐ | |||||||

| 40 | X | X | X | ● | |||||||

| 41 | X | X | X | X | ● | ● and ◐ | |||||

| 42 | X | X | X | ● | |||||||

| 43 | X | X | ● | ||||||||

| 44 | X | X | X | ● | ◐ | ||||||

| 45 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ● | ◐ | ● | ● |

| 46 | X | X | X | X | ● and ◐ | ● and ◐ | ● | ||||

| 47 | X | X | ● | ||||||||

| 48 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ||||||

| 49 | X | X | ◐ | ||||||||

| 50 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ● | ● | ||||

| 51 | X | X | X | X | X | ● | ◐ | ◐ | |||

| 52 | X | X | X | ● and ◐ | |||||||

| 53 | X | X | X | ● | ● | ||||||

| 54 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ● | ||||

| 55 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ||||||

| 56 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ● | |||||

| 57 | X | X | X | X | X | ● | |||||

| 58 | X | X | ● | ||||||||

| 59 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ● | ● | ◐ | ||

| 60 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ||||||

| 61 | X | X | ● | ||||||||

| 62 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ||||||

| 63 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ◐ | ◐ | ||||

| 64 | X | X | X | ◐ | |||||||

| 65 | X | X | X | X | ◐ | ||||||

| 66 | X | X | X | X | ● | ||||||

| 67 | X | X | X | X | ● | ◐ | |||||

| 68 | X | X | X | X | ● | ||||||

Note: “○” denotes a primarily negative/adverse impact; “●” denotes a primarily positive impact; “◐” denotes a neutral or no impact

Results

Study characteristics

Figure 1 presents information about study selection; 68 studies were included in this review. Table 3 displays information about included studies' design, setting, and sample characteristics. 26 of the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). For this review, a study was determined to be an RCT if random allocation to intervention and control groups occurred at the individual participant level at baseline. As mentioned earlier, a Cochrane review of PFCC found only one RCT conducted stringently enough for their inclusion criteria. However, unlike this review, the Cochrane review excluded premature neonates.6 14 of the RCTs in the current review took place on Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs,) including 8 NIDCAP (Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program) studies. 42 of the included studies had pre-post or other quasi-experimental designs. 42 studies took place in inpatient pediatric settings and 26 studies took place in outpatient pediatric settings. PFCC interventions were applied to a wide range of pediatric populations. The most common populations for inpatient studies were related to parents and infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) or Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU; n=29), with general pediatric inpatient settings (n=4) being the next most common, and post-surgical care and asthma studies occurring twice each.

Frequency of PFCC Components

The modal number of PFCC components per study was 2 (with 45.6% of studies having 2 PFCC components), and the mean number of PFCC components per study was 2.31 (SD=1.04). 3 studies (4.4%) had 5 PFCC components, 6 studies (8.8%) had 4 FCC components, 14 studies (20.6%) had 3 PFCC components, 31 studies (45.6%) had 2 FCC components, and 14 studies (20.6%) had 1 PFCC component.

Education from the provider to the patient and/or family (Edu) was the most commonly occurring PFCC component (n=64; 94.1%). The remaining components, in order of frequency, were InfoShare (n=38; 55.9%); SocEm (n=22; 32.4%); SDM (n=12; 17.6%); and Adapt (n=8; 11.8%). Percentages do not add up to 100% because many studies (45.6%) included more than one component.

Individual(s) Targeted by the Intervention(s)

The patient and/or family were most common targets for the intervention(s) (n=33; 48.5%). 23 studies (33.8%) had both the provider and the patient and/or family as targets, while 12 studies (17.6%) targeted the provider alone.

Outcomes measured

Among the included studies, the most frequently occurring type of outcome measured was the experience, knowledge, and/or attitudes of the patient or family (n=43; 63.2%). 41 studies (60.3%) measured health status; 22 studies (32.4%) measured patient and/or family behavior, and 14 studies (20.6%) measured provider behavior. Percentages do not add up to 100% because the majority of studies (98.5%) measured more than one type of outcome.

PFCC components and outcomes

Studies examined the positive impact of PFCC components on the following outcomes: patient and/or family behavior (63% of studies that included this indicator showed a positive impact); experience, knowledge, and attitudes of patients/family (61%); provider behavior (58%); and health status (46%).

Chi-square analysis did not show a significant relationship between the number of PFCC components included in a study and overall positive impact on outcomes. However, when individual PFCC components were examined (i.e., Edu, SocEm, InfoShare, Adapt, or SEM) in relation to outcomes, the presence of social-emotional support to the patient or family was found to be associated with positive changes in patient/family knowledge, attitudes, and/or experience; χ2 (1,N = 43) = 5.59, p =.02. No other associations between individual PFCC components and outcomes were significant.

Given the finding that education by the provider to the patient/family (Edu) was almost a universal component across all PFCC interventions (94%), we examined the additive value of the other PFCC components. InfoShare was the next most common PFCC component (in 55.9% of studies). This component focused on straightforward information from family to provider. We examined whether the presence of augmenting Edu with only information sharing from the family to the provider (i.e., Edu + InfoShare = 48.8% of studies) affected the knowledge, attitudes, and/or experience of the patient or family, as compared to the addition of SDM, Adapt, and/or SocEm (i.e., Edu + one or more of SDM, Adapt, or SocEm = 51.2% of studies). Chi-square analyses revealed improved knowledge, attitudes, and experience of the patient/family when the intervention was also augmented by SDM, Adapt, and/or SocEm as compared to when information sharing and education were the only PFCC components present: χ2 (1,N= 43) = 6.78, p =.01. No differences in other outcomes were found.

PFCC and to whom the intervention was targeted

Based on regression analyses, targeting the patient or family alone with a PFCC intervention significantly predicted better overall positive results (M=66.33%; SD=34.81) than targeting the provider alone (M=47.09%; SD=30.75) or a combination of both the provider and the patient/family (M=43.18%; SD=31.25) [F(2, 65) = 3.77, p = 0.028].

We further examined the relationship between the individual(s) targeted by the intervention and each outcome. No significant difference between results for outcomes was found by target for health status, provider behavior, or patient and family behavior. However, the percentage of positive results did significantly differ by target of the intervention for the component of experience, knowledge, and attitudes of the patient and family [F(2, 40) = 5.739, p =.006]. Specifically, those interventions that targeted only the family (M=74.8%; SD=33.47%) were significantly more effective than those that targeted both the provider and family (M=60.82%; SD=44.47%) and those that targeted the provider only (M=24.78%; SD=38.80%).

Discussion

With increasing calls for the use of PFCC in pediatric health care settings, determining the most effective components of PFCC, and the most effective ways to promote and deliver such care, is essential to improving knowledge about ways to infuse PFCC in a sustained way into health care systems. In this paper, we reviewed the current state of the evidence in the pediatric literature to develop a taxonomy of PFCC components. Our review identified five common core components of PFCC interventions (listed in order of frequency of inclusion): education by the provider to the patient and/or family, information sharing from the family to the provider, social-emotional support, shared decision-making, and adapting care to match the family background.

Studies varied widely in their use of PFCC benchmarks and outcomes, with little overlap in reported outcomes. Aside from education by the provider, studies included a variety of the remaining four PFCC components and tracked a wide range of outcomes. No single outcome was consistently included across studies that examined impact of PFCC. The most frequently examined outcomes of a PFCC intervention were patient or family experience (n=43; 63.2%) and health status (n=41; 60.3%). While education by the provider was an almost universal component of PFCC in all studies reviewed, the components that required the most individualization to patient care were the least commonly included in these interventions. Yet, our findings suggest that these more individualized components, or what has come to be known as personalized medicine, may be key to quality measures of care, particularly those related to family experience in pediatrics. The outcomes on which we report may be used as accountability metrics as health care evolves toward the use of benchmarks for quality.

As in the adult literature,18 multi-component interventions appear to be more beneficial than single-component interventions. PFCC interventions that contained only information-sharing back and forth between families and providers were less effective in improving family care experiences than those that also contained more personalized PFCC components, such as shared decision-making, adapting care to the family's background, or social-emotional support. Our findings correspond with existing evidence that patient education alone is not effective at improving patient behavior or health status; the importance of adapting care and supporting patients' confidence and skills in handling health conditions, as opposed to simply providing knowledge of the condition, has been highlighted in previous studies.19

Consistent with the literature on the impact of PFCC, descriptive statistics from the present study show overall improvements in three of the four outcomes (i.e., patient and/or family behavior, patient experience, and provider behavior). The impact on health status remains more elusive, with fewer than half of the studies showing a benefit to health status (where measured). We found evidence for specific PFCC components predicting one type of outcome (i.e., patient experience). The lack of findings for other outcomes may be due to study methodology—the majority of the studies examined acute outcomes and measured them concurrently, but patient/family experience, knowledge and/or attitudes likely precede changes in health status, patient behavior, and even provider behavior. This hypothesis is consistent with the growing literature and evidence on the impact of patient activation on health outcomes.20 Addressing patient knowledge and attitudes are key processes in patient activation as they become more actively engaged in their own health care. Thus, changes in patient experience represent an important precursor to other health-related outcomes.

Our analyses revealed that it may be more effective to target the patient and/or family alone as compared to the provider alone, or even as compared to a combination of the provider and family concurrently, particularly for outcomes related to patient/family experience. For change to be most effective or enduring, a focus on the patient and/or family is likely to be necessary. Interventions directed at patients and families are more effective at changing their experience, while interventions targeted at providers to foster change in family experience are less effective. When the provider is the target of PFCC intervention, the impact of the intervention on families may be diminished due to variability in provider delivery of PFCC. This finding is consonant with one of the key components of the Chronic Care Model, developing self-management skills.19 Patients are involved in their own health care for their entire lives. It therefore seems more effective for patients to steer their own health care choices, as opposed to the provider, who is only involved for a limited time, and may be one of many professionals involved in a patient's care. However, it may be that a difference in the interventions themselves, rather than differences in outcomes among target groups, was the cause of the differences in outcomes between target groups.

Limitations

Our review focused on five common PFCC components and four outcomes commonly examined in PFCC papers; while parsimonious, these components are not exhaustive. However, given the lack of consensus around what constitutes PFCC and which aspects of care it is purported to influence, such an approach is reasonable as a preliminary effort to capture the state of the evidence on PFCC. Additionally, included studies varied significantly in quality. Despite our attempt at an exhaustive literature review, we may have inadvertently missed studies meeting inclusion criteria. Further, cumulative evidence may be affected by the selective reporting of findings within studies. Most studies do not report fidelity to the interventions; thus it is unclear the extent to which findings, or lack thereof, may be related to how well various PFCC components are implemented. Given the limitations of the field and existing literature, our findings should be regarded as preliminary. Further rigorous studies of the five components of PFCC are needed. Finally, the prevalence of studies performed on a NICU or ICU studies may limit generalization to other settings.

Conclusion

To date, there has been a lack of attention paid to specific competencies needed by patients, providers and the health care system to optimize patient and family centered care initiatives. Calls to focus on PFCC have not been accompanied by a well-established body of work to guide care delivery. The proposed PFCC taxonomy based on our review, in consort with the existing evidence for PFCC in the literature, may provide the necessary groundwork for establishing a stronger science base for PFCC, by creating a common platform for examining key PFCC components and outcomes by which to benchmark the effectiveness of PFCC. This preliminary evidence suggests the utility of patient- and family-centered care in pediatric settings, especially when patients and families are the targets of interventions and when the provision of information is augmented with individualized components.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This study was supported by grant P30 MH090322 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the Sala Institute for Child and Family Centered Care at the NYU Langone Medical Center.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None of the authors have financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Included papers

- 1.Als H, Gilkerson L, Duffy FH, Mcanulty GB, Buehler DM, Vandenberg K, et al. A three-center, randomized, controlled trial of individualized developmental care for very low birth weight preterm infants: medical, neurodevelopmental, parenting, and caregiving effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(6):399–408. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200312000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; McAnulty G, Duffy F, Butler S, Parad R, Ringer S, Zurakowski D, et al. Individualized developmental care for a large sample of very preterm infants: health, neurobehaviour and neurophysiology. Acta paediatri. 2009;98(12):1920–1926. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAnulty GB, Butler SC, Bernstein JH, Als H, Duffy FH, Zurakowski D. Effects of the newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program (NIDCAP) at age 8 years: preliminary data. Clinical pediatrics. 2010;49(3):258–270. doi: 10.1177/0009922809335668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Als H, Duffy FH, McAnulty GB, Rivkin MJ, Vajapeyam S, Mulkern RV, et al. Early experience alters brain function and structure. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):846–857. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arauz Boudreau AD, Kurowski DS, Gonzalez WI, Dimond MA, Oreskovic NM. Latino families, primary care, and childhood obesity: a randomized controlled trial. American J Prev Med. 2013;44(3):S247–S257. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkin SL, Gesell SB, Po'e EK, Escarfuller J, Tempesti T. Culturally tailored, family-centered, behavioral obesity intervention for Latino-American preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):445–456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blauw-Hospers CH, Dirks T, Hulshof LJ, Bos AF, Hadders-Algra M. Pediatric physical therapy in infancy: from nightmare to dream? A two-arm randomized trial. Phys Ther. 2011;91(9):1323–1338. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkman WB, Hartl Majcher J, Poling LM, Shi G, Zender M, Sucharew H, et al. Shared decision-making to improve attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder care. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan CS, Molassiotis A. The effects of an educational programme on the anxiety and satisfaction level of parents having parent present induction and visitation in a postanaesthesia care unit. Pediatr Anesth. 2002;12(2):131–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper L, Gooding J, Gallagher J, Sternesky L, Ledsky R, Berns S. Impact of a family-centered care initiative on NICU care, staff and families. J Perinatol. 2007;27:S32–S37. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldbeck L, Babka C. Development and evaluation of a multi-family psychoeducational program for cystic fibrosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44(2):187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ireys HT, Chernoff R, DeVet KA, Kim Y. Maternal outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of a community-based support program for families of children with chronic illnesses. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(7):771–777. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.7.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Junnila R, Aromaa M, Heinonen OJ, Lagström H, Liuksila PR, Vahlberg T, et al. The weighty matter intervention: a family-centered way to tackle an overweight childhood. J Commun Health Nurs. 2012;29(1):39–52. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2012.645742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamerling SN, Lawler LC, Lynch M, Schwartz AJ. Family-centered care in the pediatric post anesthesia care unit: Changing practice to promote parental visitation. Journal of Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(1):5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleberg A, Westrup B, Stjernqvist K. Developmental outcome, child behaviour and mother–child interaction at 3 years of age following Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Intervention Program (NIDCAP) intervention. Early Hum Dev. 2000;60(2):123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(00)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kressin NR, Nunn ME, Singh H, Orner MB, Pbert L, Hayes C, et al. Pediatric clinicians can help reduce rates of early childhood caries: effects of a practice based intervention. Med Care. 2009;47(11):1121. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181b58867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo DZ, Sisterhen LL, Sigrest TE, Biazo JM, Aitken ME, Smith CE. Family experiences and pediatric health services use associated with family-centered rounds. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):299–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maguire CM, Walther FJ, Sprij AJ, Le Cessie S, Wit JM, Veen S. Effects of individualized developmental care in a randomized trial of preterm infants< 32 weeks. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1021–1030. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Maguire CM, Walther FJ, van Zwieten PH, Le Cessie S, Wit JM, Veen S. Follow-up outcomes at 1 and 2 years of infants born less than 32 weeks after Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):1081–1087. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCann D, Young J, Watson K, Ware RS, Pitcher A, Bundy R, et al. Effectiveness of a tool to improve role negotiation and communication between parents and nurses. Paediatric Care. 2008;20(5):14–19. doi: 10.7748/paed2008.06.20.5.14.c8255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKean K, Phillips B, Thompson A. A family-centred model of care in paediatric speech-language pathology. International J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012;14(3):235–246. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2011.604792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mello MM, Burns JP, Truog RD, Studdert DM, Puopolo AL, Brennan TA. Decision making and satisfaction with care in the pediatric intensive care unit: Findings from a controlled clinical trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5(1):40–47. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000102413.32891.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melnyk BM, Feinstein NF, Alpert-Gillis L, Fairbanks E, Crean HF, Sinkin RA, et al. Reducing premature infants' length of stay and improving parents' mental health status with the Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) neonatal intensive care unit program: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1414–e1427. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melnyk BM, Alpert-Gillis L, Feinstein NF, Crean HF, Johnson J, Fairbanks E, et al. Creating opportunities for parent empowerment: program effects on the mental health/coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e597–e607. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melnyk BM, Alpert-Gillis L, Feinstein NF, Fairbanks E, Schultz-Czarniak J, Hust D, et al. Improving cognitive development of low-birth-weight premature infants with the COPE program: A pilot study of the benefit of early NICU intervention with mothers. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(5):373–389. doi: 10.1002/nur.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morey JA, Gregory K. Nurse-led education mitigates maternal stress and enhances knowledge in the NICU. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):182–191. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824b4549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brien K, Bracht M, Macdonell K, McBride T, Robson K, O'Leary L, et al. A pilot cohort analytic study of Family Integrated Care in a Canadian neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(Suppl 1):S12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-S1-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penticuff JH, Arheart KL. Effectiveness of an Intervention to Improve Parent-Professional Collaboration in Neonatal Intensive Care. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19(2):187–202. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200504000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter SC, Forbes P, Feldman HA, Goldmann DA. Impact of patient-centered decision support on quality of asthma care in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e33–e42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preyde M, Ardal F. Effectiveness of a parent “buddy” program for mothers of very preterm infants in a neonatal intensive care unit. Can Med Assoc J. 2003;168(8):969–973. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samadi SA, McConkey R, Kelly G. Enhancing parental well-being and coping through a family-centred short course for Iranian parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2013;17(1):27–43. doi: 10.1177/1362361311435156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skuladottir A, Thome M. Changes in infant sleep problems after a family-centered intervention. Pediatr Nurs. 2002;29(5):375–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Thome M, Skuladottir A. Evaluating a family-centred intervention for infant sleep problems. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(1):5–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tzeng LF, Chiang LC, Hsueh KC, Ma WF, Fu LS. A preliminary study to evaluate a patient-centred asthma education programme on parental control of home environment and asthma signs and symptoms in children with moderate-to-severe asthma. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(9-10):1424–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van der Pal S, Maguire C, Le Cessie S, Wit J, Walther F, Bruil J. Parental experiences during the first period at the neonatal unit after two developmental care interventions. Acta Paediatri. 2007;96(11):1611–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Van Der Pal S, Maguire C, Bruil J, Le Cessie S, Wit J, Walther F, et al. Health-related quality of life of very preterm infants at 1 year of age after two developmental care-based interventions. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34(5):619–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; van der Pal S, Maguire CM, Le Cessie S, Veen S, Wit JM, Walther FJ, et al. Parental stress and child behavior and temperament in the first year after the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program. J Early Intervention. 2008;30(2):102–115. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voos KC, Ross G, Ward MJ, Yohay AL, Osorio SN, Perlman JM. Effects of implementing family-centered rounds (FCRs) in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) J Matern-Fetal Neo M. 2011;24(11):1403–1406. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.596960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wade SL, Michaud L, Brown TM. Putting the pieces together: Preliminary efficacy of a family problem-solving intervention for children with traumatic brain injury. The J Head Trauma Rehab. 2006;21(1):57–67. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weis J, Zoffmann V, Greisen G, Egerod I. The effect of person-centred communication on parental stress in a NICU: a randomized clinical trial. Acta Paediatri. 2013;102(12):1130–1136. doi: 10.1111/apa.12404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westermann G, Verheij F, Winkens B, Verhulst FC, Van Oort FV. Structured shared decision-making using dialogue and visualization: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westrup B, Kleberg A, von Eichwald K, Stjernqvist K, Lagercrantz H. A randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the effects of the newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program in a Swedish setting. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1):66–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kleberg A, Westrup B, Stjernqvist K, Lagercrantz H. Indications of improved cognitive development at one year of age among infants born very prematurely who received care based on the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) Early Hum Dev. 2002;68(2):83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(02)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Westrup B, Hellström-Westas L, Stjernqvist K, Lagercrantz H. No indications of increased quiet sleep in infants receiving care based on the newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program (NIDCAP) Acta Paediatri. 2002;91(3):318–322. doi: 10.1080/08035250252833996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Westrup B, Lagercrantz H, Stjernqvist K. Preschool outcome in children born very prematurely and cared for according to the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) Acta Paediatri. 2004;93(4):498–507. doi: 10.1080/08035250410023548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kleberg A, Hellström-Westas L, Widström AM. Mothers' perception of Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) as compared to conventional care. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(6):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wielenga JM, Smit BJ, Unk LK. How satisfied are parents supported by nurses with the NIDCAP® model of care for their preterm infant? J Nurs Care Qual. 2006;21(1):41–48. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200601000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wielenga JM, Smit BJ, Merkus MP, Kok JH. Individualized developmental care in a Dutch NICU: short-term clinical outcome. Acta Paediatri. 2007;96(10):1409–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wielenga JM, Smit BJ, Merkus MP, Wolf MJ, Van Sonderen L, Kok J. Development and growth in very preterm infants in relation to NIDCAP in a Dutch NICU: two years of follow-up. Acta Paediatri. 2009;98(2):291–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Won D. Effects of Programmed Information on Coping Behavior and Emotions of Mothers of Young Children Undergoing IV Procedures. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2006;36(8):1301–1307. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2006.36.8.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woods DT, Catroppa C, Giallo R, Matthews J, Anderson VA. Feasibility and consumer satisfaction ratings following an intervention for families who have a child with acquired brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012;30(3):189–198. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2012-0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright K, Giger JN, Norris K, Suro Z. Impact of a nurse-directed, coordinated school health program to enhance physical activity behaviors and reduce body mass index among minority children: A parallel-group, randomized control trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(6):727–737. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borhani F, Najafi MK, Rabori ED, Sabzevari S. The effect of family-centered empowerment model on quality of life of school–aged children with thalassemia major. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2011;16(4):292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bouvé LR, Rozmus CL, Giordano P. Preparing parents for their child's transfer from the PICU to the pediatric floor. Appl Nurs Res. 1999;12(3):114–120. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(99)80012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brady PW, Brinkman WB, Simmons JM, Yau C, White CM, Kirkendall ES, et al. Oral antibiotics at discharge for children with acute osteomyelitis: a rapid cycle improvement project. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(6):499–507. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark N, Gong M, Schork M, Kaciroti N, Evans D, Roloff D, et al. Long-term effects of asthma education for physicians on patient satisfaction and use of health services. Eur Respir J. 2000;16(1):15–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16a04.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davison KK, Jurkowski JM, Li K, Kranz S, Lawson HA. A childhood obesity intervention developed by families for families: results from a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dudas RA, Lemerman H, Barone M, Serwint JR. PHACES (Photographs of Academic Clinicians and Their Educational Status): a tool to improve delivery of family-centered care. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(2):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byers JF, Lowman LB, Francis J, Kaigle L, Lutz NH, Waddell T, et al. A Quasi-Experimental Trial on Individualized, Developmentally Supportive Family-Centered Care. JOGN Nurs. 2006;35(1):105–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Felder-Puig R, Maksys A, Noestlinger C, Gadner H, Stark H, Pfluegler A, et al. Using a children's book to prepare children and parents for elective ENT surgery: results of a randomized clinical trial. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gray JE, Safran C, Davis RB, Pompilio-Weitzner G, Stewart JE, Zaccagnini L, et al. Baby CareLink: using the internet and telemedicine to improve care for high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1318–1324. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hughes AR, Stewart L, Chapple J, McColl JH, Donaldson MD, Kelnar CJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of a best-practice individualized behavioral program for treatment of childhood overweight: Scottish Childhood Overweight Treatment Trial (SCOTT) Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e539–e546. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stewart D, Law M, Burke-Gaffney J, Missiuna C, Rosenbaum P, King G, et al. Keeping It TogetherTM: an information KIT for parents of children and youth with special needs. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32(4):493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC, Weinberg ME, Wang SM, MacLaren JE, et al. Family-centered preparation for surgery improves perioperative outcomes in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(1):65–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fortier M, Blount R, Wang SM, Mayes L, Kain Z. Analysing a family-centred preoperative intervention programme: a dismantling approach. Brit J Anaesth. 2011:aer010. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lammi BM, Law M. The effects of family-centred functional therapy on the occupational performance of children with cerebral palsy. Can J Occup Ther. 2003;70(5):285–297. doi: 10.1177/000841740307000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peters KL, Rosychuk RJ, Hendson L, Coté JJ, McPherson C, Tyebkhan JM. Improvement of short-and long-term outcomes for very low birth weight infants: Edmonton NIDCAP trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1009–1020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hart CN, Drotar D, Gori A, Lewin L. Enhancing parent–provider communication in ambulatory pediatric practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1):38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuntaros S, Wichiencharoen K, Prasopkittikun T, Staworn D. Effects of family-centered care on self-efficacy in participatory involvement in child care and satisfaction of mothers in PICU. Thai J Nurs Res. 2007;11(3):203. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monzavi R, Dreimane D, Geffner ME, Braun S, Conrad B, Klier M, et al. Improvement in risk factors for metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in overweight youth who are treated with lifestyle intervention. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1111–e1118. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clark NM, Gong M, Schork MA, Evans D, Roloff D, Hurwitz M, et al. Impact of education for physicians on patient outcomes. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):831–836. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Dulmen AM, Holl RA. Effects of continuing paediatric education in interpersonal communication skills. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159(7):489–495. doi: 10.1007/s004310051316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Porter SC, Kohane IS, Goldmann DA. Parents as partners in obtaining the medication history. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(3):299–305. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Porter SC, Kaushal R, Forbes PW, Goldmann D, Kalish LA. Impact of a patient-centered technology on medication errors during pediatric emergency care. Amb Pediatr. 2008;8(5):329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cho Y, Hirose T, Tomita N, Shirakawa S, Murase K, Komoto K, et al. Infant Mental Health Intervention for Preterm Infants in Japan: Promotions of Maternal Mental Health, Mother–Infant Interactions, and Social Support by Providing Continuous Home Visits until the Corrected Infant Age of 12 Months. Inf Mental Hlth J. 2013;34(1):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Welch MG, Hofer MA, Stark RI, Andrews HF, Austin J, Glickstein SB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of Family Nurture Intervention in the NICU: assessments of length of stay, feasibility and safety. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):148. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Als H, Duffy F, McAnulty G, Fischer C, Kosta S, Butler S, et al. Is the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) effective for preterm infants with intrauterine growth restriction&quest. J Perinat. 2010;31(2):130–136. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; McAnulty G, Duffy FH, Kosta S, Weisenfeld NI, Warfield SK, Butler SC, et al. School-age effects of the newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program for preterm infants with intrauterine growth restriction: preliminary findings. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Als H, Duffy FH, McAnulty G, Butler SC, Lightbody L, Kosta S, et al. NIDCAP improves brain function and structure in preterm infants with severe intrauterine growth restriction. J Perinat. 2012;32(10):797–803. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kleberg A, Warren I, Norman E, Mörelius E, Berg AC, Mat-Ali E, et al. Lower stress responses after Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program care during eye screening examinations for retinopathy of prematurity: a randomized study. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1267–e1278. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ullenhag A, Persson K, Nyqvist KH. Motor performance in very preterm infants before and after implementation of the newborn individualized developmental care and assessment programme in a neonatal intensive care unit. Acta Paediatri. 2009;98(6):947–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press; 2001. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernabeo E, Holmboe ES. Patients, providers, and systems need to acquire a specific set of competencies to achieve truly patient-centered care. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):250–258. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson BH. Family-centered care: Four decades of progress. Families, Systems, & Health. 2000;18(2):137. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care. Patient-and family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shields L, Zhou H, Pratt J, Taylor M, Hunter J, Pascoe E. Family-centred care for hospitalised children aged 0-12 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004811.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shields L, Pratt J, Davis L, Hunter J. Family-centred care for children in hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004811.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0804116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, Bona JR, Fricks L, Jenkins-Tucker S, et al. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophrenia research. 2010;118(1):264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alegría M, Sribney W, Perez D, Laderman M, Keefe K. The role of patient activation on patient–provider communication and quality of care for US and foreign born Latino patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24(3):534–541. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sledge WH, Lawless M, Sells D, Wieland M, O'Connell MJ, Davidson L. Effectiveness of peer support in reducing readmissions of persons with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(5):541–544. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. The American journal of managed care. 2011;17(1):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, Staelin R, Roe MT, Wolosin RJ, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2010;3(2):188–195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.900597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shields L, Pratt J, Hunter J. Family centred care: a review of qualitative studies. Journal of clinical nursing. 2006;15(10):1317–1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlow JH, Ellard DR. Psycho-educational interventions for children with chronic disease, parents and siblings: an overview of the research evidence base. Child: care, health and development. 2004;30(6):637–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health affairs. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health affairs. 2013;32(2):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo DZ, Sisterhen LL, Sigrest TE, Biazo JM, Aitken ME, Smith CE. Family experiences and pediatric health services use associated with family-centered rounds. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):299–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]