Abstract

Domesticated carrots, Daucus carota subsp. sativus, are the richest source of β-carotene in the US diet, which, when consumed, is converted into vitamin A, an essential component of eye health and immunity. The Y2 locus plays a significant role in beta-carotene accumulation in carrot roots, but a candidate gene has not been identified. To advance our understanding of this locus, the genetic basis of β-carotene accumulation was explored by utilizing an advanced mapping population, transcriptome analysis, and nucleotide diversity in diverse carrot accessions with varying levels of β-carotene. A single large effect Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) on the distal arm of chromosome 7 overlapped with the previously identified β-carotene accumulation QTL, Y2. Fine mapping efforts reduced the genomic region of interest to 650 kb including 72 genes. Transcriptome analysis within this fine mapped region identified four genes differentially expressed at two developmental time points, and 13 genes differentially expressed at one time point. These differentially expressed genes included transcription factors and genes involved in light signaling and carotenoid flux, including a member of the Di19 gene family involved in Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis, and a homolog of the bHLH36 transcription factor involved in maize carotenoid metabolism. Analysis of nucleotide diversity in 25 resequenced carrot accessions revealed a drastic decrease in diversity of this fine-mapped region in orange cultivated accessions as compared to white and yellow cultivated and to white wild samples. The results presented in this study provide a foundation to identify and characterize the gene underlying β-carotene accumulation in carrot.

Keywords: carotenoids, Daucus carota L., genotyping-by-sequencing, RNA-sequencing, QTL

Carotenoids are a subgroup of isoprenoid compounds produced by algae, bacteria, fungi, and plants that absorb light during photosynthetic light capture. They also provide photoprotection, attract pollinators and seed dispersers, and serve as precursors for the production of important downstream compounds including norisoprenoids, apocarotenoids, strigolactones, and abscisic acid (Walter and Strack 2011; Alder et al. 2012; Ruiz-Sola and Rodríguez-Concepción 2012; Ellison 2016). Humans, and most animals, cannot produce carotenoids and therefore they must acquire them through their diet (Walter and Strack 2011). Colorful carotenoids accumulated by some animals also ensure reproductive success during courtship or may be involved in defense mechanisms (Cazzonelli 2011). Humans convert provitamin A carotenoids, such as α- and β-carotene, into vitamin A, which is critical for maintaining normal vision, a healthy immune system, and effective cellular communication and differentiation (Fraser and Bramley 2004; Biesalski et al. 2007; Rao and Rao 2007).

Carotenoids in plants are synthesized in differentiated plastids including the chloroplasts of green tissues and chromoplasts of flower petals, fruits, and roots (Yuan et al. 2015). The storage roots of orange carrots, Daucus carota L. (2n = 2x = 18), accumulate high concentrations of α- and β-carotene, making carrot one of the richest sources of dietary provitamin A carotenoids. Indeed, orange carrots account for 28% of the β-carotene and 67% of α-carotene, derived from plant sources, in the US diet (Simon et al. 2009; Just et al. 2009). However, the genetic mechanisms that control substantial carotene accumulation in carrot, particularly β-carotene, are only beginning to be understood.

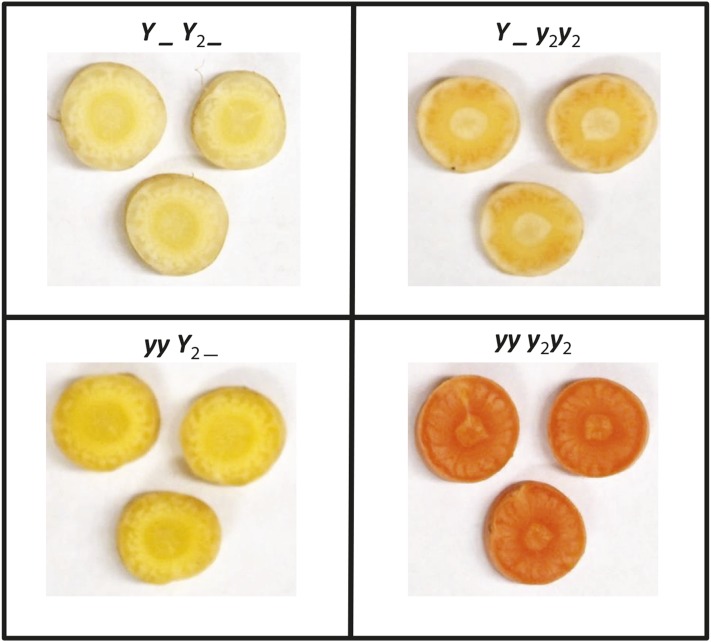

In carrot, the Y and Y2 loci explain most of the phenotypic variation among white, yellow, and orange storage roots (Laferriere and Gabelman 1968; Buishand and Gabelman 1979; Simon 1996; Bradeen et al. 1997; Just et al. 2007; Iorizzo et al. 2016). In this model, Y_Y2_ conditions white, yyY2_ yellow, Y_ y2y2 pale orange, and yyy2y2 orange roots (Figure 1). Previous research identified several Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) associated with carotenoid accumulation, and mapped the Y and Y2 loci to chromosomes 5 and 7, respectively (Santos and Simon 2002; Just et al. 2009; Cavagnaro et al. 2011), and a SCAR marker was developed for Y2 to facilitate marker-assisted selection for beta-carotene (Bradeen et al. 1997; Bradeen and Simon 1998), which can be challenging to visually phenotype in certain segregating populations and in diverse genetically uncharacterized diverse germplasm, especially in early development. Recently, researchers utilized Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) and RNA-sequencing to identify a candidate gene for the Y locus, DCAR_032551 (Iorizzo et al. 2016). Interestingly, this candidate is not a carotenoid biosynthetic gene, but rather shares homology with the Arabidopsis homolog PEL (Pseudo-Etiolation in Light), which is involved in the regulation of photomorphogenesis and de-etiolation (Ichikawa et al. 2006). Several carrot studies have found associations between carotenoid content and carotenoid biosynthetic genes, including a study by Arango et al. (2014), which identified a Carotene Hydroxylase (CYP97A3) homolog that contributed to increased carotenoid content due to increased amounts of α-carotene. Further, a candidate gene association analysis by Jourdan et al. (2015) suggested total carotenoid and β-carotene quantities were significantly associated with the genes Zeaxanthin Epoxidase (ZEP), Phytoene Desaturase (PDS), and Carotenoid Isomerase (CRTISO). To verify whether these genes underlie the Y2 locus, a whole-genome integrative approach was used.

Figure 1.

Visual appearance of the four phenotypic classes of carrot storage root color conferred by the Y and Y2 loci. Y_Y2_ (white) top left, yyY2_ (yellow) bottom left, Y_y2y2 (pale orange) top right, and yyy2y2 (dark orange) bottom right.

A better understanding of β-carotene accumulation and the genetic architecture of the Y2 locus will contribute to the genetic improvement of nutritional content in carrots and may provide novel targets to pursue increased carotenoid accumulation in other crop species. To address this objective, we utilized the recently published carrot genome to identify candidate genes and explore the genetic control of beta-carotene accumulation in a mapping population segregating for the Y2 locus. While the Y2 gene accounts for most of the accumulation of both alpha- and beta-carotene, in orange carrots, we focused on β-carotene accumulation in this study since five additional QTL were found to account for α-carotene accumulation in a mapping study (Santos and Simon 2002), with Carotene Hydroxylase having a particularly large effect (Arango et al. 2014). Additionally, we used RNA-sequencing to identify differentially expressed genes within the Y2 fine-mapped region as well as in the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) and carotenoid pathways. Further, we evaluated SNPs from white, yellow, and orange resequenced carrot accessions to determine if nucleotide diversity was reduced around the Y2 locus among orange carrots. Finally, we developed codominant markers to assist in selection for beta-carotene accumulation in segregating populations.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

The F4 population 74,146 was derived from a cross between USDA carrot inbred line B493 (Simon and Peterson 1990), an orange-rooted line, and QAL (Queen Anne’s Lace), a wild-type white-rooted carrot from the United States. Plants were grown the summer of 2013 at the University of Wisconsin, Hancock Agricultural Research Station, and 213 roots were selected for phenotyping and genotyping. Population 74,146 was preliminarily evaluated and found to be homozygous recessive yy, but segregating for root color associated with the Y2 locus. An additional 192 samples from the 74,146 population were grown at the University of Wisconsin, Walnut Street Greenhouse and used for fine mapping. To analyze the segregation ratios between parents and progeny, two F4:5 populations (98,024 and 98,026) derived from self-pollination of the 74,146 population were grown in the summer of 2013 at the UW Madison Hancock Research Station, and an additional two similarly derived populations (98,029 and 98,032) were grown during the winter of 2014–2015 at the University of California, Desert Research and Extension Center.

Carotenoid and color evaluation

Carotenoid content was quantified using lyophilized root tissue for HPLC analysis as modified from Simon and Wolff (1987) and Simon et al. (1989). Briefly, 0.1 g of lyophilized carrot root tissue was crushed and then soaked in 2.0 ml of petroleum ether at 4°. After 15 hr, 300 µl of the petroleum ether extract was added to 700 μl of methanol, eluted through a Rainin Microsorb-MV column, and analyzed on a Millipore Waters 712 WISP HPLC system. Synthetic β-carotene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used in each independent run as a reference standard for calibration. β-Carotene was quantified by absorbance at 450 nm. Concentrations are described in microgram per gram dry weight (DW). Additionally, phenotypic estimates of carotenoid content were taken using a visual categorical scale. Carrot roots were cross cut at mid-root and then categorized into two phenotypic groups: yellow or orange. Goodness-of-fit for a single gene model was calculated using visual categories.

GBS

Total genomic DNA of individual plants was isolated from lyophilized leaves of 4-wk old plants following the protocol described by Murray and Thompson (1980) with modifications by Boiteux et al. (1999). DNA was quantified using Quantus PicoGreen ds DNA Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), and normalized to 10 ng/μl. GBS, as described by Elshire et al. (2011), was carried out at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Biotechnology Center with minimal modification and half-sized reactions. Briefly, DNA samples were digested with ApeKI, barcoded, and pooled for sequencing, and 80–85 pooled samples were run per single Illumina HiSequation 2000 lane, using paired-end, 100 nt reads and v3 SBS reagents (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Paired-end sequencing reads were preprocessed with bb.tassel (https://github.com/dsenalik/bb) to add barcodes to the reverse reads for TASSEL compatibility. The TASSEL-GBS pipeline version 4.3.7 was used to call SNPs as described by Bradbury et al. (2007) and Glaubitz et al. (2014). SNPs were filtered for <10% missing data for genotype and marker, >10% minor allele frequency, and no more than two alleles. This set of 78,850 SNPs was submitted to dbSNP at NCBI under BioProject PRJNA348698. Any remaining missing genotype calls were imputed using Beagle v4.0 with parameters burnin-its = 10, phase-its = 10, and impute-its = 10 (Browning and Browning 2016). Imputed markers were further filtered for minimum allele frequency >0.3 and maximum allele frequency <0.7, leaving 33,712 SNPs. Marker-trait associations were carried out with molecular markers considered as fixed effects in a linear model implemented in the GLM function of TASSEL (Bradbury et al. 2007). The carrot genome assembly v2.0 (GenBank accession LNRQ01000000) was used as a reference to identify marker locations (Iorizzo et al. 2016). The genome-wide significance threshold was determined by the Bonferroni method, P ≤ 0.05 (Bland and Altman 1995).

Linkage map construction

Heterozygous SNPs, with an allele ratio expected to be 1:1, were eliminated if the ratio of the two alleles was <0.3 or >0.7, leaving 2999 high quality markers for linkage mapping (Supplemental Material, Table S1 in File S1). Genetic linkage analysis and map construction was executed in JoinMap 4 (Van Ooijen 2006) as previously described (Cavagnaro et al. 2014). The 74,146 map was analyzed as an F2 population. Markers ascertained to be the result of false double recombination events were identified using CheckMatrix version 248 (http://www.atgc.org/XLinkage) and removed. The following parameters were used for the calculation: Haldane’s mapping function, LOD ≥3.0, REC frequency ≤0.4, goodness-of-fit jump threshold for removal of loci = 5.0, number of added loci after which a ripple was performed = 1, and third round = no. At LOD >10, with <10% missing data for marker and genotype, 616 markers were grouped into nine linkage groups (Figure S1)

QTL mapping

QTL analysis was carried out using the R package R/qtl (Broman and Sen 2009). For the single QTL model interval analyses, genotype probabilities were calculated with a step value of 1 over the entire linkage map. The “scanone” function used the normal phenotype model (model = “normal”) and the Haley-Knott regression method (method = “hk”) as parameters. After running 1000 permutations with an assumed genotyping error rate of 0.001, a LOD of 4.01 was set as the QTL significance threshold. Confidence intervals for each QTL were defined as the 1.5 LOD drop off flanking the peak of the QTL. Linkage maps and QTL were drawn using Mapchart 2.1 software (Voorrips 2002).

Fine mapping

Based on visual inspection of recombination events depicted in the TASSEL viewer, and confidence intervals identified in the QTL analysis, fine-mapping was conducted with an additional 192 individuals using 13 newly developed SNPs spanning positions 32,973,430–34,339,369 on chromosome 7. A set of 13 primer pairs were designed using Primer3 (Untergasser et al. 2012), targeting specific loci spanning the genomic region associated with β-carotene accumulation. Marker and primer coordinates have been adjusted to reflect the most recent genome release (D. carota v2.0, GenBank accession LNRQ01000000). DNA was extracted from freeze-dried leaves as previously described. PCR and Sanger sequencing were performed as described in Iorizzo et al. (2012). Primer information can be found in Table S2 in File S1.

Nucleotide diversity

An analysis of seven wild (white; Y_Y2_), seven cultivated nonorange (white; Y_Y2_ or yellow; yyY2_), and 11 cultivated orange (yyy2y2) resequenced carrot accessions (Table S3 in File S1, Iorizzo et al. 2016) identified 1,378,264 SNPs on Chromosome 7 that were used to estimate nucleotide diversity (π) in TASSEL (Bradbury et al. 2007) with the method described by Nei and Li (1979). Nucleotide diversity was calculated using a sliding window = 1000 and 500 SNPs per step. Genome coordinates were adjusted to reflect the most recent carrot genome (D. carota Ver.2, Bioproject PRJNA268187).

Transcriptome analysis

Carrot root tissue was collected from three yellow (yyY2Y2) and three orange (yyy2y2) pigmented biological replicates, plants from the progenitor F2 population of population 74,146, at 40 (time point one) and 80 (time point two) days after planting (DAP). Two time points were sampled to detect potential variation in expression across development. Time point one corresponds to the onset of visual detection of carotenoid accumulation in the storage root, and time point two corresponds to the onset of the plateau in carotenoid accumulation. Total RNA was extracted from storage root tissue using the TRIzol Plus RNA Purification Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Contaminating DNA was removed with the TurboDNA-free kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). RNA quantity and integrity was confirmed with an Experion RNA StdSens Analysis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). All samples had RQI values >8.0.

For each sample, a 133-nt insert size paired-end library was prepared at the Biotechnology Center, UW-Madison. Libraries were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq2000 lanes using 2 × 100 nt reads. Reads were filtered with Trimmomatic version 0.32 with adapter trimming and using a sliding window of length ≥50 and quality ≥28, i.e., “ILLUMINACLIP:adapterfna:2:40:15 LEADING:28 TRAILING:28 MINLEN:50 SLIDINGWINDOW:10:28.”

Short reads from each replicate were independently mapped against the carrot genome sequence (GenBank accession LNRQ01000000.1) using Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012) and Tophat2 (Kim et al. 2013) (Table S4 in File S1). Reads for each gene (exon level) available from the V1.0 gene annotation of the carrot genome (Iorizzo et al. 2016) were quantified with the featurecounts (Liao et al. 2014) standalone package, using only reads that mapped uniquely to the genome.

Pearson correlations between samples were calculated between technical replicates (Table S5 in File S1) and samples A11, A11r, B3, B3r, B4, B4r, C3, C5, C6, and E1 were discarded due to high correlation with noncorresponding replicates (Table S6 in File S1). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in four unique comparisons: (1) yellow time point one vs. orange time point one, (2) yellow time point two vs. orange time point two, (3) orange time point one vs. orange time point two, and (4) yellow time point one vs. yellow time point two, using a Negative Binomial test implemented in the DESeq package (Anders and Huber 2010).

Candidate gene sequence alignment

Four primer pairs spanning the candidate gene DCAR_026175 were developed with Primer3 (Table S2 in File S1, Untergasser et al. 2012). Extracted DNA from a yellow (Y2Y2) and orange (y2y2) plant from the 71,746 population was amplified using DCAR_026175-specific primers to produce high-quality PCR amplicons and purified using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA sequencing of the PCR amplicons was performed at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center. Sequences were aligned using Sequencher version 5.0 DNA sequence analysis software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI).

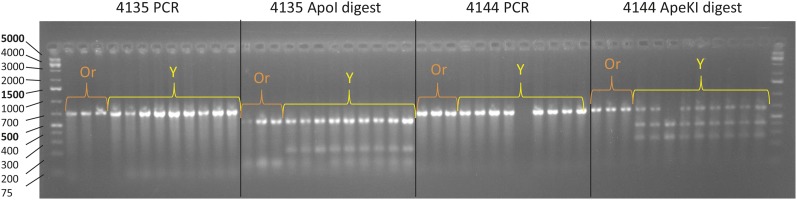

Cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences (CAPS) marker development

PCR amplicons containing SNPs were identified during fine-mapping and sequence data were used to locate possible restriction enzyme site polymorphisms using the program NEBcutter V2.0 (Vincze et al. 2003). Two polymorphic PCR amplicons, 4135 and 4144, that differed for restriction enzyme sites ApoI and ApeKI, were used to develop CAPs markers. For CAPs marker 4135ApoI, cleavage of the amplified fragment was carried out according to manufacturer’s recommendations. In summary, the digestion took place at 37° for 15 min using the following conditions: 15 μl of the PCR product, 2 μl (1×) buffer CutSmart (New England Biolabs), and 1 μl (5 U) of the restriction enzyme Apol (New England Biolabs) in a final volume of 20 μl. For CAPs marker 4144cApeKI, cleavage was carried out at 75° for 15 min using the following conditions: 15 μl of the PCR product, 2 μl (1×) buffer 3.1 (New England Biolabs), and 1 μl of (5 U) of the restriction enzyme ApeKI (New England Biolabs) in a final volume of 20 μl. Digestion products were separated on a 2% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer.

Data availability

SNPs from the 74,146 mapping population were deposited in dbSNP under BioProject PRJNA348698. Raw reads from the 29 carrot transcriptomes were deposited under BioProject PRJNA350691. Resequenced carrot accessions were obtained from Bioproject PRJNA291976. The authors state that all other data and necessary code for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are available as Supplemental Material.

Results

Phenotypic evaluation and inheritance

Segregation ratios for the F4 74,146 population and F4:5 families fit a single gene model with yellow color dominant to orange (Table 1 and Table S7 in File S1). These results agree with previous studies indicating that the dominant Y2 allele reduces β-carotene accumulation resulting in yellow root color (Buishand and Gabelman 1979; Simon 1996; Just et al. 2009). β-Carotene content for 158 yellow and 52 orange roots averaged 0.5 and 77.7 μg g−1 DW, respectively (Table S7 in File S1).

Table 1. Color segregation ratios observed in carrot populations derived from family 74,146 that segregates for the Y2 gene.

| Population | Location | Parent Root Color | Inferred Parental Genotype | Yellow | Orange | Expected Segregation Ratio | χ2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 74,146 | WI 2012 | Yellow | Y2y2 | 158 | 52 | 3:1 | 0.006 | 0.94 |

| 98,024 | WI 2013 | Yellow | Y2y2 | 79 | 17 | 3:1 | 2.72 | 0.1 |

| 98,026 | WI 2013 | Orange | y2y2 | 0 | 32 | 0:1 | 0 | 1 |

| 98,029 | CA 2014 | Yellow | Y2Y2 | 102 | 0 | 1:0 | 0 | 1 |

| 98,032 | CA 2014 | Orange | y2y2 | 0 | 134 | 0:1 | 0 | 1 |

Mapping and QTL analysis

The v4.0 TASSEL GBS pipeline analysis of population 74,146 called 512,427 SNPs. Filtering and imputation left 33,712 high quality SNPs scored in 210 plants. The distribution of markers across the nine chromosomes ranged from 2029 to 5168, with an average of one GBS marker every 11.3 kb (Table S8 in File S1).

To identify the genetic region that includes the Y2 trait locus, HPLC data (β-carotene content) was used to identify marker-trait associations with the 33,712 GBS SNPs. Genome-wide tests to identify significant association were carried out using a standard GLM analysis in TASSEL (Elshire et al. 2011). Inspection of the Q-Q plot confirmed no inflation in P-values (data not shown). A region of high significance was found on the distal end of chromosome 7 for β-carotene content, as observed by Just et al. (2009) (Figure 2A and Table S9 in File S1).

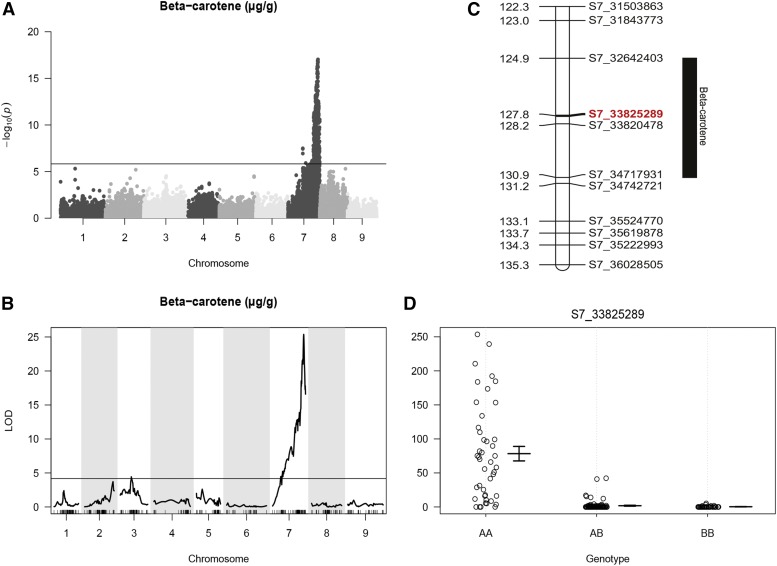

Figure 2.

Mapping and QTL analysis for carrot β-carotene content. (A) Manhattan plot for β-carotene concentration. Horizontal line indicates Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. (B) QTL analysis for β-carotene concentration. Horizontal line indicates QTL significance threshold. (C) Linkage map of the distal end of chromosome 7 showing the QTL for β-carotene content. Black bar covers the 1.5 LOD drop off region. The most significant marker, S7_33,825,289, is highlighted in red. (D) Marker effect plot for S7_33,825,289, within the QTL region on chromosome 7. AA represents the homozygous recessive genotype (y2y2), while AB and BB represent the heterozygous and homozygous dominant genotypes (Y2_), respectively. Vertical axis indicates the quantity of beta-carotene (μg/g).

QTL analysis was also carried out for β-carotene concentration. After filtering for missing data and segregation distortion, 616 high quality SNPs were called in 176 plants. The distribution of markers across the nine linkage groups ranged from 33 to 118 (Table S10 in File S1), with an average of one marker every 1.9 cM (Figure S1 and Table S11 in File S1).

A single QTL on the distal arm of chromosome 7 was identified for β-carotene concentration, with a maximum LOD value of 25.4 with the nearest marker at S7_33,825,289 (Figure 2, B and C). The QTL for beta-carotene concentration explained 48.5% of the phenotypic variation. This QTL overlaps with the region identified by GLM analysis. An effect plot for the most significant marker, S7_33,825,289, was used to determine the contribution of allelic states (A, H, B) on the phenotypic expression of the trait (Figure 2D). In the homozygous recessive state (AA) this marker was associated with an increase of >80 μg g−1 DW β-carotene.

Fine mapping

Flanking the region of highest significance on chromosome 7, two recombinants were found to border a region of ∼1.0 Mb (Figure 3A). The flanking markers of this region were S7_33,019,341 and S7_33,979,543. The locations of recombination events were used as starting points for fine mapping.

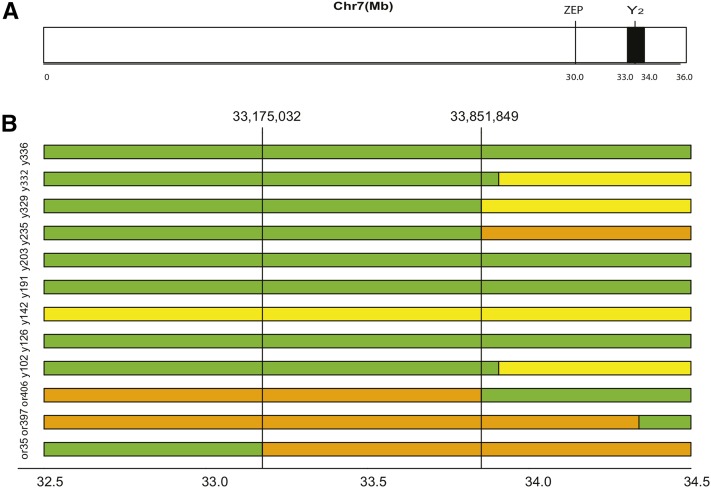

Figure 3.

Fine-mapping the Y2 locus on chromosome 7. (A) Chromosome 7 including the location of Y2, delimited by SNP markers S7_33,019,341 and S7_33,979,543 in black, and the nearest carotenoid biosynthetic gene, ZEP at 30,085,761. (B) Fine-mapping of the Y2 region, delimited by SNP markers S7_33,175,032 and S7_33,851,849. Orange homozygous recessive, yellow heterozygous, and yellow homozygous dominant genotypes are represented by orange, green, and yellow bars, respectively. Genotypes used for fine mapping are shown to the left of the colored bars. Horizontal axis values indicate physical location (megabase).

The inclusion of 192 additional plants for fine mapping reduced the candidate region from 1 Mb to ∼650 kb on chromosome 7 between markers 33,175,032 and 33,851,849 (Figure 3B). Samples with linkage blocks between markers 33,175,032 and 33,851,849 harboring the “B” and “H” alleles had low β-carotene levels and were classified as Yellow, Y, whereas samples associated with the “A” allele had high β-carotene content and were classified as Orange, Or (Table S7 in File S1). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that high β-carotene is controlled by the Y2 locus (Just et al. 2009). This region is included within the previously mapped QTL region associated with the Y2 trait (Cavagnaro et al. 2011; Just et al. 2009).

In total, 72 genes have been predicted in the 650 kb fine-mapped region (Iorizzo et al. 2016; Table 2 and Tables S12 and S13 in File S1). Only one gene from the MEP or carotenoid pathway, 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase, (DXR), was found in the region of interest. The most highly represented genes in the region of interest were related to nucleotide or DNA binding, while other common groups included biosynthetic processes, transporter and kinase activities.

Table 2. The 72 genes within the Y2 fine-mapped region. Subject description is the top Blastp hit in SwissProt or TrEMBL.

| Gene Annotation | Subject Description | Gene Annotation | Subject Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCAR_026103a | Butyrate–CoA ligase AAE11 | DCAR_026139 | Pantothenate kinase 2 |

| DCAR_026104 | Ceramide kinase | DCAR_026140 | Iron-sulfur cluster assembly protein 1 |

| DCAR_026105 | Pyruvate decarboxylase 2 | DCAR_026141 | Probable boron transporter 2 |

| DCAR_026106 | 30S ribosomal protein S4 | DCAR_026142 | GDSL esterase/lipase |

| DCAR_026107a | Auxin response factor 6 | DCAR_026143 | Phosphoenolpyruvate/phosphate translocator 1 |

| DCAR_026108b | Replication protein A 70 kD DNA-binding subunit C | DCAR_026144 | Glutathione S-transferase 3 |

| DCAR_026109b | Probable galactinol-sucrose galactosyltransferase 5 | DCAR_026145 | Protein EXECUTER 2 |

| DCAR_026110 | Chalcone synthase | DCAR_026146 | Replication protein A 70 kD DNA-binding subunit E |

| DCAR_026111a | Chalcone synthase 4 | DCAR_026147 | Replication protein A 70 kD DNA-binding subunit A |

| DCAR_026112 | 40S ribosomal protein SA | DCAR_026148b | Nucleolar GTP-binding protein 1 |

| DCAR_026113 | Calcium-dependent protein kinase 19 | DCAR_026149 | Secretory carrier-associated membrane protein |

| DCAR_026114 | Probable alpha-mannosidase I MNS5 | DCAR_026150 | Probable calcium-binding protein CML16 |

| DCAR_026115a | Calmodulin-binding protein 60 A | DCAR_026151 | Wall-associated receptor kinase 3 |

| DCAR_026116a | Calmodulin-binding protein 60 B | DCAR_026152 | NEDD8-specific protease 1 |

| DCAR_026117 | LIM domain-containing protein WLIM1 | DCAR_026153 | Glutaredoxin-C1 |

| DCAR_026118 | ABC transporter C family member 1 | DCAR_026154a | Homeobox protein knotted-1-like 6 |

| DCAR_026119 | Nucleobase-ascorbate transporter 6 | DCAR_026155 | Serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A |

| DCAR_026120 | Probable lysine-specific demethylase ELF6 | DCAR_026156 | Factor of DNA methylation 3 |

| DCAR_026121 | Rac-like GTP-binding protein 3 | DCAR_026157 | Protein MICRORCHIDIA 6 |

| DCAR_026122 | Probable cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel 20 | DCAR_026158 | Pantothenate kinase 2 |

| DCAR_026123 | Putative FBD-associated F-box protein At5g56400 | DCAR_026159 | Probable apyrase 7 |

| DCAR_026124 | Protein HAPLESS 2-B | DCAR_026160 | Short-chain dehydrogenase TIC 32 |

| DCAR_026125 | U-box domain-containing protein 19 | DCAR_026161 | FKBP12-interacting protein of 37 kD |

| DCAR_026126a | Transcription factor bHLH36 | DCAR_026162 | Tryptophan aminotransferase-related protein 2 |

| DCAR_026127a | Probable polygalacturonase | DCAR_026163 | Oleosin 5 |

| DCAR_026128 | T-complex protein 1 subunit gamma | DCAR_026164 | Protein LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES |

| DCAR_026129 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | DCAR_026165 | Putative pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein |

| DCAR_026130 | Protein EXECUTER 2, chloroplastic | DCAR_026166 | Histone deacetylase 6 |

| DCAR_026131 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase HT1 | DCAR_026167 | Histone deacetylase 6 |

| DCAR_026132 | Peroxisomal membrane protein PEX14 | DCAR_026168 | Histone deacetylase 6 |

| DCAR_026133 | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase | DCAR_026169a | U-box domain-containing protein 12 |

| DCAR_026134a | Rhodanese-like domain-containing protein 10 | DCAR_026170a | Primary amine oxidase |

| DCAR_026135a | Probable inactive poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase | DCAR_026171 | Ferric reduction oxidase 8 |

| DCAR_026136 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase ATM | DCAR_026172 | Protein NBR1 homolog |

| DCAR_026137 | Dof zinc finger protein DOF5.6 | DCAR_026173a | Uncharacterized protein |

| DCAR_026138 | 50S ribosomal protein L12 | DCAR_026174 | Oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 3 |

| DCAR_026175b | Protein DEHYDRATION-INDUCED 19 homolog 5 |

Genes differentially expressed at one time point

Genes differentially expressed at both time points

Nucleotide diversity

Resequencing data were used to evaluate nucleotide diversity between wild white (Y_Y2_), white (Y_Y2_), and yellow (yyY2_) cultivated, and orange (yyy2y2) cultivated accessions in the region associated with high β-carotene accumulation on chromosome 7. Several chromosomal regions had reduced nucleotide diversity, comparing cultivated and wild accessions. However only one region, encompassing the Y2 fine mapped region was associated with a decrease in diversity, comparing orange cultivated with nonorange (yellow and white) cultivated carrots (Figure S2).

Transcriptome analysis

β-Carotene content ranged from 202 to 846 μg g−1 DW among the three orange (y2y2) biological replicates (plants), whereas it ranged from 4 to 30 μg g−1 DW among the three yellow (Y2Y2) biological replicates (Table S14 in File S1). Transcriptome analysis comparing orange and yellow samples at both time points detected 3626 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Tables S15 and S16 in File S1). Within the 650 kb fine-mapped region containing the Y2 gene, 13 DEGs were identified at one time point (Table 2 and Tables S17 and S18 in File S1) while only four genes were differentially expressed at both time points—Replication protein A 70 kD DNA-binding subunit C (DCAR_026108), Galactinol-sucrose galactosyltransferase 5 (DCAR_026109), Nucleolar GTP-binding protein 1 (DCAR_026148), and Protein DEHYDRATION-INDUCED 19 homolog 5 (Di19) (DCAR_026175) (Table 2 and Tables S19 and S20 in File S1).

To date, 68 gene families involved in the MEP or carotenoid biosynthetic pathway have been identified in carrot (Iorizzo et al. 2016). Within the MEP and carotenoid pathways six genes were differentially expressed at one time point (PSY-1, CYP707a-2, NSY-2, CYP707a-1, PSY-3, and CCD1-1), and two were differentially expressed at both time points (GPPS-1 and LUT5), where both genes were downregulated in orange carrots relative to yellow (Figure S3 and Table S18 in File S1). The only MEP or carotenoid gene within the Y2 fine mapped region, DXR, was not differentially expressed. Between time point one and time point two, 10 genes were differentially expressed in orange plants, and only one gene was differentially expressed between yellow plants (Table S18 in File S1).

DCAR_026175 sequence analysis

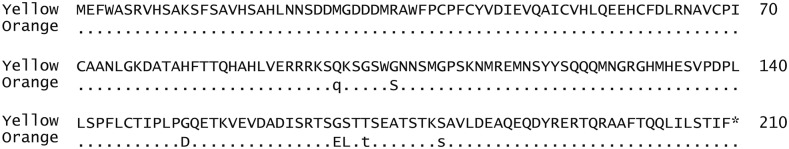

Of the differentially expressed genes in the Y2 fine mapped region, only DCAR_026175 was differentially expressed at both time points and had lowered expression in orange genotypes, consistent with the recessive nature of the orange phenotype. Sequence analysis comparing a yellow homozygous plant with an orange homozygous plant identified three synonymous mutations, and four nonsynonymous mutations in the protein coding region of the candidate gene DCAR_026175 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of DCAR_026175 between yellow and orange carrot roots in population 74,146. The full length amino acid sequence is shown with dots indicating no change, lowercase letters represent synonymous mutations, and uppercase letters denote nonsynonymous mutations.

CAPs marker development

Several genes within the 650 kb fine mapped region were analyzed for sequence polymorphisms to develop CAPs markers that can be used to aid in marker-assisted selection for β-carotene accumulation. DCAR_026127 and DCAR_026133 had SNPs within restriction enzyme sites for ApeKI and ApoI, respectively, and these polymorphisms were used to develop CAPs markers (Table S2 in File S1). CAPs markers cosegregated with color for all samples used to fine-map the Y2 region, and with all domesticated samples in a panel of unrelated yellow and orange carrot accessions (Figure 5, Figure S4, and Table S21 in File S1).

Figure 5.

Gel electrophoresis image of the two CAPs markers within the Y2 fine-mapped region. Amplicon 4135 is within DCAR_026133 and amplicon 4144 is within DCAR_026127. GeneRuler 1 kb Plus DNA ladder sizes are shown to the left of the gel image. Or indicates orange samples, and Y indicates yellow samples from population 74,146.

Discussion

β-Carotene accumulation has been extensively studied in many crop and model species including Arabidopsis (Ruiz-Sola and Rodríguez-Concepción 2012), maize (Owens et al. 2014), and tomato (Yuan et al. 2015). However, in carrot, which is one of the highest naturally occurring sources of β-carotene, the genetic regulation of accumulation is still unclear.

Previous studies in carrot have mapped QTL for carotenoid accumulation with AFLP markers (Santos and Simon 2002), and/or have utilized candidate genes from the MEP and carotenoid biosynthetic pathways to identify the genetic control of β-carotene accumulation (Just et al. 2007, 2009; Jourdan et al. 2015; Iorizzo et al. 2016). However, this is the first study to use a whole-genome approach along with a transcriptome analysis to better understand the regulation of high β-carotene accumulation. Analysis of an F4 mapping population segregating for β-carotene content found a single highly significant region on the distal region of chromosome 7 associated with an 80-fold increase in β-carotene, agreeing with previous studies (Just et al. 2009; Cavagnaro et al. 2011). This region accounts for 48.5% of the phenotypic variation in β-carotene content within the 74,146 population. Remaining phenotypic variation may be explained by smaller effect QTL modifying β-carotene accumulation (Santos and Simon 2002) and by nongenetic sources. Utilizing 192 additional samples, the region of interest was fine mapped to a region of 650 kb. Analysis of the nucleotide diversity in 25 resequenced white, yellow and orange carrots revealed a drastic decrease in nucleotide diversity surrounding the fine mapped Y2 region in orange carrots, compared to white and yellow, indicating directional selection for the Y2 haplotype in domesticated orange carrots. Within this region, 72 genes have been annotated and only one gene, DXR, is part of the isoprenoid pathway. A previous study by Jourdan et al. (2015) found total carotenoid and beta-carotene content were significantly associated with polymorphisms within the genes ZEP (DCAR_025735), PDS (DCAR_016085), and CRTISO (DCAR_013459); however, none of these genes are located within the Y2 region that was fine mapped in our study. It is likely that the limited density of sequences/markers, 17 genes distributed across the whole genome, used by Jourdan et al. (2015), combined with the fact that ZEP, which is located ∼3 Mb upstream from the Y2 region of interest, may have resulted in a false association, due to linkage to the selective sweep that likely took place around the Y2 region that we characterized in this study.

Although DXR mapped to the region of interest in our study, it was not differentially expressed at either time point. DXR has been shown to be important in carotenoid flux regulation. In Arabidopsis, it appears to be a rate-determining enzyme and overexpression in seedlings increases carotenoid production (Estévez et al. 2001; Carretero-Paulet et al. 2006). However, a study in tomato did not find evidence for a limiting role of DXR in carotenoid biosynthesis (Rodríguez-Concepción et al. 2001). Similarly, a recent study in carrot found that DXR has a limited regulatory role on carotenoid accumulation in carrot roots and leaves (Simpson et al. 2016). We therefore believe DXR is not the underlying candidate gene for β-carotene accumulation within the Y2 region.

Differential expression in the Y2 fine-mapped region

Differential expression was analyzed at two time points in an analysis of yellow (yyY2Y2) and orange (yyy2y2) storage root tissue. Within the Y2 fine-mapped region, 17 genes were differentially expressed, and, of these, only four were differentially expressed at both time points, Replication protein A 70 kDa DNA-binding subunit C (DCAR_026108), Galactinol-sucrose galactosyltransferase 5 (DCAR_026109), Nucleolar GTP-binding protein 1 (DCAR_026148), and Protein DEHYDRATION-INDUCED 19 homolog 5 (Di19) (DCAR_026175) (Table 2). Of these four genes, only Di19 was downregulated in orange (y2y2) storage roots, as would be expected for a recessive trait. The combination of fine-mapping with transcriptome analysis points to Di19 as a strong candidate for the Y2 gene.

Sequence analysis of the DCAR_026175 coding region identified three synonymous and four nonsynonymous SNPs between homozygous yellow and orange carrot roots (Figure 4). The nonsynonymous mutations occur in the C-terminal domain of Di19, and represent candidate mutations altering expression and downstream function of the gene. Members of the Arabidopsis Di19 gene family can function in an ABA-independent fashion and are regulated by other abiotic stimuli such as member AtDi19-7, which has been implicated in regulating light signaling and responses (Milla et al. 2006). Consequently, altered expression of Di19 could potentially influence the coordinated production of chlorophyll and carotenoids that occurs during photomorphogenesis. Of the remaining 13 genes in the region of interest that were differentially expressed at one time point, one interesting candidate, DCAR_026126, shares homology with a bHLH36 transcription factor. Ye et al. (2015) observed that bHLH expression was highly correlated with carotenoid metabolism, suggesting a complex underlying regulatory network controls carotenoid flux. Similarly, Endo et al. (2016) found bHLH1 from citrus has a similar function to Arabidopsis activation-tagged bri1 suppressor 1 (ATBS1) interacting factor (AIF), which may be directly involved in carotenoid metabolism in mature citrus fruit. Based on these observations, future studies should examine the functional role of DCAR_026175 and DCAR_026126 in β-carotene regulation and accumulation.

Differential expression in the isoprenoid pathway

Within previously characterized isoprenoid genes, but outside of the Y2 region, five genes (PSY-1, CYP707a-2, NSY-2, CYP707a-1, and PSY-3) were differentially expressed at time point one, and one gene at time point two (CCD1-1) (Table S18 in File S1). PSY is considered a rate-limiting enzyme in carotenoid biosynthesis and changes in expression have been linked to flux in the pathway (Maass et al. 2009; Rodríguez-Vilalon et al. 2009). Plants typically have several PSY genes that exhibit tissue-specific expression such as in tomato and citrus where PSY-1 is found in fruits, PSY-2 in leaves, and PSY-3 in roots (Peng et al. 2013; Fantini et al. 2013). We found PSY-1 to be downregulated and PSY-3 to be upregulated in orange carrot storage roots as compared to yellow roots. Other studies in carrot have found a relationship between increased PSY-1 and PSY-2 expression between white and nonwhite carrots (yellow or orange), but this relationship begins to dissolve when comparing expression between yellow and orange roots (Bowman et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014). Therefore, expression of PSY-1 and PSY-2 in root tissue may be more associated with total carotenoid content, including xanthophylls and carotenes, rather than β-carotene specifically. It is also likely that PSY-1 and PSY-2 have less of a role in carotenoid accumulation in the roots than in other anatomical parts including leaves and fruits.

Two genes in this study, both outside of the Y2 region, were differentially expressed at both time points (LUT5 and GPPS-1). A study by Arango et al. (2014) concluded an 8-nt insertion in the LUT5 gene in orange carrots contributed to dysfunction of this gene, and, consequently, increased carotenoid content due to α-carotene accumulation. Our study found LUT5 expression was not detectable in orange carrots, which agrees with Arango et al. (2014) and provides further evidence for the role of LUT5 in carotene accumulation. Interestingly, LUT5 (DCAR_023843) is on chromosome 7 at position 6,061,642 Mb, which is located near the second lowest region of nucleotide diversity, in orange compared to nonorange (white and yellow) carrots (Figure S2). Since a decrease in expression of LUT5 leads to an increase in α-carotene and total carotenes, it is likely this region of the genome also underwent selection to increase total carotenoid content in carrot storage roots. Therefore both Y2 and LUT5 have played an important role in the accumulation of carotenoids in carrot. Within the Y2 fine mapped region, 10 genes were differentially expressed between the two time points in orange roots and one gene in yellow roots (Table S18 in File S1), illustrating the importance of understanding carotenogenesis across development and root maturity to fully appreciate the complexity of carotenoid accumulation. Future studies including coexpression network analysis should be conducted across multiple time points during plant growth to better understand carotenoid accumulation throughout storage root development.

Narrowing down potential Y2 candidates

In many plants, carotenoid biosynthetic genes are responsible for the accumulation of carotenoids; however, there are several other mechanisms outside of this pathway that regulate accumulation. These mechanisms include transcriptional regulation of carotenoid biosynthetic and degradation genes, regulation of sequestration and storage, plastid biogenesis, and regulatory genes (Giuliano and Diretto 2007; Li and Yuan 2013; Yuan et al. 2015; Nisar et al. 2015). Several genes including DDB1 and CHCR in tomato and Or in cauliflower are not carotenoid biosynthetic genes, but rather they regulate or sequester carotenoids, resulting in accumulation (Lieberman et al. 2004; Lu et al. 2006; Kilambi et al. 2013). Similarly, a recent analysis of 98 plastidal methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) and carotenoid pathway genes in carrot revealed no overlap with the Y or Y2 QTL (Iorizzo et al. 2016). Instead, the Y candidate gene, DCAR_032551, is involved in the regulation of photomorphogenesis and de-etiolation. Within the fine mapped region of Y2 there are several transcription factors, including DCAR_026126, DCAR_026130, DCAR_026137, and DCAR_026145, that could potentially be involved in the transcriptional regulation of β-carotene accumulation. These candidate genes are also worthy of further investigation in future studies. Further, it is important to note that differential expression of the candidate gene for Y2 may not have been detected in our analysis. Potential reasons for this are: (1) the developmental time point or tissue type to capture differential expression may not have been evaluated, (2) protein levels of translated Y2 mRNA may not correlate with mRNA expression levels, as has been reported in other studies (Payne 2015), and (3) the number of transcriptome biological replications was too small to detect important but subtle differences in gene expression.

Beyond expanding the number of root developmental stages and number of biological replicates evaluated, an alternative tactic to further narrow the list of Y2 candidates includes taking an association mapping approach which may drastically narrow the region of interest. Initial estimates of LD in carrot (unreported) show rapid decay (1–2 kb) making it an ideal crop for association mapping given the correct marker density. Another potential strategy to narrow candidates is to analyze the corresponding steady state levels of candidate proteins since this may be more accurate of gene expression than mRNA transcript abundance. Well-supported candidates should then be subject to functional assays such as complementation studies or genome editing to validate their function in β-carotene accumulation. Additionally, improved carrot genome annotation may strengthen or reduce support for candidates identified by increasing the depth of coverage in this region, and sequencing the transcriptomes of various pigmented carrots at different developmental stages and in different tissue types may lead to novel annotations that were not identified in the initial annotation efforts.

Marker development for β-carotene accumulation

Previous research identified a QTL for β-carotene and total carotenoids on a ∼30 cM region on chromosome 7. Visual phenotyping of β-carotene accumulation due to Y2 segregation is challenging in certain segregating carrot populations and at early developmental time points, so within this QTL a codominant marker Y2mark was created to facilitate marker-assisted breeding (Bradeen et al. 1997; Bradeen and Simon 1998). Y2mark maps to the carrot genome at position 35,382,784 Mb, ∼2 Mb away from the newly fine-mapped Y2 region. We have developed two closely linked codominant markers, 4135Apol1 and 4144ApeKI, to more accurately select y2y2 plants with increased β-carotene accumulation. These markers have been tested not only within the mapping population, but also in a group of unrelated genetic materials, and have proven to be very accurate in predicting orange and nonorange phenotypes (Figure S4).

By enhancing our knowledge of the regulation of biosynthetic processes and flux through the carotenoid pathway, undoubtedly new possibilities will emerge to utilize this information to accelerate plant improvement. Special interest in carotenoid biosynthesis in plants is attributed to the highly beneficial chemical properties of carotenoids compounds that are well recognized in promoting human health, for example, their antioxidant properties and provitamin A activity. Our research has utilized an integrative, whole-genome approach to better understand β-carotene accumulation in carrot, while looking beyond known biosynthetic genes to discover novel mechanisms regulating carotenoid biosynthesis, accumulation and storage.

Conclusions

In this study, we report the first fine mapping of a major locus, Y2, controlling β-carotene accumulation in carrot. This strategy reduced the previously described region from ∼30 cM, based upon QTL analysis, with ∼1 recombination event every 388 kb (Iorizzo et al. 2016) to 650 kb. In the fine-mapped region, we identified 17 differentially expressed genes, of which only four were differentially expressed at both time points. Genes within the Y2 fine-mapped region, and especially those with differential expression, are of particular interest for candidate gene identification and functional analyses in the future. Additionally, the marker development for the Y2 region provides a convenient molecular tool to discriminate low and high β-carotene content carrots.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.g3journal.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/g3.117.043067/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rob Kane (deceased) for field assistance. Brian Yandell and Patrick Krysan helped to initiate this project and provided valuable comments. The authors also thank Hailey Shanovich and Stephanie Miller for technical assistance. The authors thank the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center DNA Sequencing Facility for providing genotyping-by-sequencing library preparation and sequencing services. S.E. was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant 1202666. M.I. was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project 1008691.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: E. Grotewold

Literature Cited

- Alder A., Jamil M., Marzorati M., Bruno M., Vermathen M., et al. , 2012. The path from β-carotene to carlactone, a strigolactone-like plant hormone. Science 335: 1348–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Huber W., 2010. DESeq: differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11: R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango J., Jourdan M., Geoffriau E., Beyer P., Welsch R., 2014. Carotene hydroxylase activity determines the levels of both alpha-carotene and total carotenoids in orange carrots. Plant Cell 26: 2223–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesalski H. K., Chichili G. R., Frank J., von Lintig J., Nohr D., 2007. Conversion of β-carotene to retinal pigment. Vitam. Horm. 75: 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J. M., Altman D. G., 1995. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ 310: 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiteux L. S., Fonseca M. E., Simon P. W., 1999. Effects of plant tissue and DNA purification method on randomly amplified polymorphic DNA-based genetic fingerprinting analysis in carrot. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 124: 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman M. J., Willis D. K., Simon P. W., 2014. Transcript abundance of phytoene synthase 1 and phytoene synthase 2 is association with natural variation of storage root carotenoid pigmentations in carrot. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 139: 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury P. J., Zhang Z., Kroon D. E., Casstevens T. M., Ramdoss Y., et al. , 2007. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23: 2633–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradeen J. M., Simon P. W., 1998. Conversion of an AFLP fragment linked to the carrot Y2 locus to a simple, codominant, PCR-based marker form. Theor. Appl. Genet. 97: 960–967. [Google Scholar]

- Bradeen J. M., Vivek B. S., Simon P. W., 1997. Detailed genetic mapping of the Y2 carotenoid locus in carrot. J. Appl. Genet. 38: 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Broman K. W., Sen S., 2009. A Guide to QTL Mapping with R/qtl. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Browning B. L., Browning S. R., 2016. Genotype imputation with millions of reference samples. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98: 116–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buishand J. G., Gabelman W. H., 1979. Investigations on the inheritance of color and carotenoid content in phloem and xylem of carrot roots (Daucus carota L.). Euphytica 28: 611–632. [Google Scholar]

- Carretero-Paulet L., Cairo A., Botella-Pavia P., Besumbes O., Campos N., et al. , 2006. Enhanced flux through the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis plants overexpression deoxyxyluluse 5-phosphate reductoisomerase. Plant Mol. Biol. 62: 683–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavagnaro P. F., Chung S.-M., Manin S., Yildiz M., Ali A., et al. , 2011. Microsatellite isolation and marker development in carrot-genomic distribution, linkage mapping, genetic diversity analysis and marker transferability across Apiaceae. BMC Genomics 12: 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavagnaro P. F., Iorizzo M., Yildiz M., Senalik D., Parsons J., et al. , 2014. A gene-derived SNP-based high resolution linkage map of carrot including the location of QTL conditioning root and leaf anthocyanin pigmentation. BMC Genomics 15: 1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzonelli C. I., 2011. Carotenoids in nature: insights from plants and beyond. Funct. Plant Biol. 38: 833–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison S. L., 2016. Carotenoids|Physiology, pp. 670–675 in Encyclopedia of Food and Health, edited by Caballero B., Finglas P. M., Toldra F. Elsevier, Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Elshire R. J., Glaubitz J. C., Sun Q., Poland J. A., Kawamoto K., et al. , 2011. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS One 6: e19379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Fujii H., Sugiyama A., Nakano M., Makajima N., et al. , 2016. Overexpression of a citrus basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor (CubHLH1), which is homologous to Arabidopsis activation-tagged bri1 suppressor 1 interaction factor genes, modulates carotenoid metabolism in transgenic tomato. Plant Sci. 243: 35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estévez J. M., Cantero A., Reindl A., Reichler S., León P., 2001. 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase, a limiting enzyme for plastidic isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 22901–22909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantini E., Falcone G., Frusciante S., Giliberto L., Giuliano G., 2013. Dissection of tomato lycopene biosynthesis through virus-induced gene silencing. Plant Physiol. 163: 986–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser P. D., Bramley P. M., 2004. The biosynthesis and nutritional uses of carotenoids. Prog. Lipid Res. 43: 228–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano G., Diretto G., 2007. Of chromoplasts and chaperones. Trends Plant Sci. 12: 529–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaubitz J. C., Casstevens T. M., Lu F., Harriman J., Elshire R. J., et al. , 2014. TASSEL-GBS: a high capacity genotyping by sequencing analysis pipeline. PLoS One 9: e90346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa T., Nakazawa M., Kawashima M., Iizumi H., Kuroda H., et al. , 2006. The FOX hunting system: an alternative gain-of-function gene hunting technique. Plant J. 48: 974–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorizzo M., Senalik D., Szklarczyk M., Grzebelus D., Spooner D., et al. , 2012. De novo assembly of the carrot mitochondrial genome using next generation sequencing of whole genomic DNA provides first evidence of DNA transfer into an angiosperm plastid genome. BMC Plant Biol. 12: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorizzo M., Ellison S., Senalik D., Zeng P., Satapoomin P., et al. , 2016. A high-quality carrot genome assembly provides new insights into carotenoid accumulation and asterid genome evolution. Nat. Genet. 48: 657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan M., Gagne S., Dubois-Laurent C., Maghraoui M., Huet S., et al. , 2015. Carotenoid content and root color of cultivated carrot: a candidate-gene association study using an original broad unstructured population. PLoS One 10: e0116674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just B. J., Santos C. A. F., Fonseca M. E. N., Boituex L. S., Olozia B. B., et al. , 2007. Carotenoid biosynthesis structural genes in carrot (Daucus carota): isolation, sequence-characterization, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers and genome mapping. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114: 693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just B. J., Santos C. A., Yandell B. S., Simon P. W., 2009. Major QTL for carrot color are positionally associated with carotenoid biosynthetic genes and interact epistatically in a domesticated x wild carrot cross. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119: 1155–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilambi H. V., Kumar R., Sharma R., Sreelakshmi Y., 2013. Chromoplast-specific carotenoid-associated protein appears to be important for enhanced accumulation of carotenoids in hp1 tomato fruits. Plant Physiol. 161: 2085–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., et al. , 2013. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14: R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laferriere L., Gabelman W. H., 1968. Inheritance of color, total carotenoids, alpha-carotene, and beta-carotene in carrots, Daucus carota. L. Proc. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 93: 408–418. [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L., 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Yuan H., 2013. Chromoplast biogenesis and carotenoid accumulation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 539: 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Smyth G. K., Shi W., 2014. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30: 923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M., Segev O., Gilboa N., Lalazar A., Levin I., 2004. The tomato homolog of the gene encoding UV-damaged DNA binding protein 1 (DDB1) underlined as the gene that causes the high pigment-1 mutant phenotype. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108: 1574–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S., Van Eck J., Zhou X., Lopez A. B., O’Halloran D. M., et al. , 2006. The cauliflower Or gene encodes a DnaJ cysteine-rich domain-containing protein that mediates high levels of β-carotene accumulation. Plant Cell 18: 3594–3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass D., Arango J., Wust F., Beyer P., Welsch R., 2009. Carotenoid crystal formation in Arabidopsis and carrot roots caused by increased phytoene synthase protein levels. PLoS One 4: e6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milla M.A.R., Townsend J., Chang I., Cushman J. C., 2006. The Arabidopsis AtDi19 gene family encodes a novel type of Cys2/His2 zinc-finger protein implicated in ABA-independent dehydration, high-salinity stress and light signaling pathways. Plant Mol. Biol. 61: 13–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. G., Thompson W. F., 1980. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8: 4321–4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M., Li W. H., 1979. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76: 5269–5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisar N., Li L., Lu S., Khin N. C., Pogson B. J., 2015. Carotenoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant 8: 68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens B. F., Lipka A. E., Magallanes-Lundback M., Tiede T., Diepenbrock C. H., et al. , 2014. A foundation for provitamin A biofortification of maize: genome-wide association and genomic prediction models of carotenoid levels. Genetics 198: 1699–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne S. H., 2015. The utility of protein and mRNA correlation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G., Wang C., Song S., Fu X., Azam M., et al. , 2013. The role of 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase and phytoene synthase gene family in citrus carotenoid accumulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 71: 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao A. V., Rao L. G., 2007. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol. Res. 55: 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Concepción M., Ahumada I., Diez-Juez E., Sauret-Güeto S., Lois L. M., et al. , 2001. 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase and plastid isoprenoid biosynthesis during tomato fruit ripening. Plant J. 27: 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Vilalon A., Gas E., Rodríguez-Concepción M., 2009. Phytoene synthase activity controls the biosynthesis of carotenoids and the supply of their metabolic precursors in dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 60: 424–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Sola M. Á., Rodríguez-Concepción M., 2012. Carotenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: a colorful pathway. Arabidopsis Book 10: e0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos C. A., Simon P. W., 2002. QTL analyses reveal clustered loci for accumulation of major provitamin A carotenes and lycopene in carrot roots. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268: 122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon P. W., 1996. Inheritance and expression of purple and yellow storage root color in carrot. J. Hered. 87: 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Simon P. W., Peterson C. E., 1990. B493 and B9304, carrot inbreds for use in breeding, genetics, and tissue culture. HortScience 25: 815. [Google Scholar]

- Simon P. W., Wolff X. Y., 1987. Carotenes in typical and dark orange carrots. J. Agric. Food Chem. 35: 1017–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Simon P. W., Wolff X. Y., Peterson C. E., Kammerlohr D. S., 1989. High carotene mass carrot population. HortScience 24: 174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Simon P. W., Pollak L. M., Clevidence B. A., Holden J. M., Haytowitz D. B., 2009. Plant breeding for human nutritional quality. Plant Breed. Rev. 31: 325–392. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson K., Quiroz L. F., Rodríguez-Concepción M., Stange C. R., 2016. Differential contribution of the first two enzymes of the MEP pathway to the supply of metabolic precursors for carotenoid and chlorophyll biosynthesis in carrot (Daucus carota). Front. Plant Sci. 7: 1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A., Cutcutache I., Koressaar T., Ye J., Faircloth B. C., et al. , 2012. Primer3–new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooijen J. W., 2006. JoinMap 4.0: Software for the Calculation of Genetic Linkage Maps in Experimental Populations. Kyazma B.V., Wageningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Vincze T., Posfai J., Roberts R. J., 2003. NEBcutter: a program to cleave DNA with restriction enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 3688–3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorrips R. E., 2002. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 93: 77–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M. H., Strack D., 2011. Carotenoids and their cleavage products: biosynthesis and functions. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28: 663–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Ou C.-G., Zhuang F.-Y., Ma Z.-G., 2014. The dual role of phytoene synthase genes in carotenogenesis in carrot roots and leaves. Mol. Breed. 34: 2065–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Hu T., Yang C., Li H., Yang M., et al. , 2015. Transcriptome profiling of tomato fruit development reveals transcription factors associated with ascorbic acid, carotenoid and flavonoid biosynthesis. PLoS One 10: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H., Zhang J., Nageswaran D., Li L., 2015. Carotenoid metabolism and regulation in horticultural crops. Hortic. Res. 2: 15036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

SNPs from the 74,146 mapping population were deposited in dbSNP under BioProject PRJNA348698. Raw reads from the 29 carrot transcriptomes were deposited under BioProject PRJNA350691. Resequenced carrot accessions were obtained from Bioproject PRJNA291976. The authors state that all other data and necessary code for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are available as Supplemental Material.