Abstract

Background

A single base pair mutation in the sodium channel confers knock-down resistance to pyrethroids in many insect species. Its occurrence in Anopheles mosquitoes may have important implications for malaria vector control especially considering the current trend for large scale pyrethroid-treated bednet programmes. Screening Anopheles gambiae populations for the kdr mutation has become one of the mainstays of programmes that monitor the development of insecticide resistance. The screening is commonly performed using a multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) which, since it is reliant on a single nucleotide polymorphism, can be unreliable. Here we present a reliable and potentially high throughput method for screening An. gambiae for the kdr mutation.

Methods

A Hot Ligation Oligonucleotide Assay (HOLA) was developed to detect both the East and West African kdr alleles in the homozygous and heterozygous states, and was optimized for use in low-tech developing world laboratories. Results from the HOLA were compared to results from the multiplex PCR for field and laboratory mosquito specimens to provide verification of the robustness and sensitivity of the technique.

Results and Discussion

The HOLA assay, developed for detection of the kdr mutation, gives a bright blue colouration for a positive result whilst negative reactions remain colourless. The results are apparent within a few minutes of adding the final substrate and can be scored by eye. Heterozygotes are scored when a sample gives a positive reaction to the susceptible probe and the kdr probe. The technique uses only basic laboratory equipment and skills and can be carried out by anyone familiar with the Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique. A comparison to the multiplex PCR method showed that the HOLA assay was more reliable, and scoring of the plates was less ambiguous.

Conclusion

The method is capable of detecting both the East and West African kdr alleles in the homozygous and heterozygous states from fresh or dried material using several DNA extraction methods. It is more reliable than the traditional PCR method and may be more sensitive for the detection of heterozygotes. It is inexpensive, simple and relatively safe making it suitable for use in resource-poor countries.

Background

The successful trials of pyrethroid insecticide-treated nets for malaria control in various endemic settings has led to the Roll Back Malaria initiative adopting the approach as one of the cornerstones of its malaria control programmes [1-3]. However, the increasing prevalence of insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae, the major vector of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, threatens to compromise the successful use of insecticide-treated materials [4]. Resistance to pyrethroid insecticides was first seen in An. gambiae sensu stricto in West Africa [5] and has subsequently been detected in East Africa [6]. Whilst much of the observed resistance is thought to have been selected for by the use of pesticides in agriculture [7], there is already some evidence in East Africa that the introduction of treated bednets has selected for reduced susceptibility to permethrin [6].

One allele commonly associated with resistance to permethrin is the knock-down resistance or kdr allele. This allele encodes a modified voltage-gated sodium channel that has reduced sensitivity to DDT and pyrethroids. Molecular studies identified a single point mutation in the kdr allele that causes an amino acid substitution in domain II of the protein [8]. Two different mutations have been found in An. gambiae; the first causes a leucine to phenylalanine amino acid change and has been found in several West African countries [8-11], whilst the second found mainly in East African populations causes a leucine to serine substitution at the same amino acid position [6,12]. The importance of these mutations to the control of Anopheles mosquitoes is not yet fully understood. However, monitoring its frequency, as a rapid indicator of the development of resistance, should be an integral component of insecticide resistance management programmes.

The most commonly used method for identifying the kdr mutations involves a multiplexed PCR technique. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) detection is problematic with simple PCR approaches, requiring the use of highly toxic reagents [13] or prohibitively expensive equipment. Many of these approaches are difficult to transfer to field laboratories where the ability to monitor gene frequencies is most acutely needed. The technique detailed here, adapted from one originally designed by W.C. Black IV requires only a thermal cycler and provides an easily interpretable, colorimetric genotyping system. No toxic reagents are involved. While this system has been specifically designed to assay kdr resistance allele frequencies in An. gambiae, it is broadly applicable where target-site insensitivity is an important mechanism of resistance to insecticides and to chemotherapeutics.

Methods

Mosquito strains and bioassays

Specimens were obtained from laboratory colonies of RSP (a homozygous line for the East African kdr mutation), Kisumu (a susceptible line from Kenya, established in 1953), and Odumasi (a partially resistant line, not yet fixed for the West African kdr mutation). Adult females were stored at -20°C before extraction. Field caught specimens were collected using resting catches from Asembo in western Kenya in May 2004, and by pyrethrum spray collections in Odumasi, Ghana in June 2003. Samples were dried over silica gel for later analysis.

PCR

All PCR reactions were performed in ABI GeneAmp® PCR system 2700 or MJ Research PTC-200 DNA Engine thermal cyclers. Primers Agd1 and Agd2 [8] were used to amplify a 293 bp fragment from domain II of the voltage-sensitive sodium channel protein sequence (EMBL #Y13592). PCR was carried out with the DNA of 1/80th or 1/160th of a single mosquito in a 25 μl volume with a final concentration of 1x Buffer, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP's (Sigma dNTP-100), 0.3 μM each primer (Qiagen), Taq DNA polymerase 0.034 U/μl (Qiagen 201203). Reaction conditions were 94°C for 4 min, 25 cycles of 94°C for 25 sec, 56°C for 20 sec, 72°C for 8 sec; and a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min (modified from [12]). Artificial heterozygote controls were created using DNA from two homozygous samples.

DNA from a single mosquito was extracted using the Livak method, [14] or the Ballinger Crabtree method [15] and resuspended in 100 μl or 200 μl of ddH20.

Species identification was carried out on all specimens using a PCR method [16]and specimens were characterized for kdr status using PCR methods [8,12]. PCR products were visualized under UV light on 1.5% agarose, 0.5x TBE gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Hot Ligation

3 μl of PCR product from the above reaction was used in a hot ligation with Detector and Reporter oligonucleotides (MWG Biotech) (Table 1). Aliquots were made for each oligo pair containing 1 μM detector and 1 μM reporter in ddH20. A 20 μl reaction volume containing 1x Buffer, 50 nM detector and reporter mix and 0.05 U/μl Ampligase® (Cambio A32250) was set up for each oligo pair. Four reactions were set up for each PCR sample to test for the East and West resistant alleles and the susceptible allele (two different oligo pairs must be used to test for the susceptible allele in these assays, as the potential oligo binding site differs by one base pair). The reaction conditions were 95°C for 5 min, 25 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for West African kdr detection or 60°C for East African kdr detection for 2 min; with a final hold at 4°C. Ligated products were kept at 4°C in the dark and used as soon as possible for SNP analysis.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences used in the Hot Ligation

| Description | Oligo Name | bp Positiona | Oligo sequence 5' – 3' | Modifications |

| Suspt. East kdr detector | Kdr104L-DTe | 311-15i | ATTTGCATTACTTACGACTA | 5' Biotin |

| Resist. East kdr detector | Kdr104S-DTe | 311-15i | ATTTGCATTACTTACGACTG | 5' Biotin |

| East kdr reporter | Kdr104-RTe | 291–310 | AATTTCCTATCACTACAGTG | 5' Phosphorylation 3' Fluorescein |

| Suspt. West kdr detector | Kdr104L-DTw | 312-16i | AATTTGCATTACTTACGACT | 5' Biotin |

| Resist. West kdr detector | Kdr104F-DTw | 312-16i | AATTTGCATTACTTACGACA | 5' Biotin |

| West kdr reporter | Kdr104-RTw | 292–311 | AAATTTCCTATCACTACAGT | 5' Phosphorylation 3' Fluorescein |

aUsing sequence from Martinez-Torres et al., as reference; i intron 2 position.

SNP Detection

96-well plates (VWR 402 200 402) were prepared using 100 μl of 5 μg/ml streptavidin (Sigma S4762) per well. The plate was left to dry overnight and then washed 4 times in 250 μl of 1 x PBS with 0.1% v/v Tween 20. Buffer was removed by tapping the plate upside down and 200 μl of blocking solution (1x PBS, 0.1%v/v Tween 20, 2%w/v BSA) added for 1 hour. Four more washes of 250 μl with PBS were carried out before plates were covered with a plastic seal and stored at 4°C for up to one week.

20 μl of TNE (10 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl) was added to the hot ligation reaction and then all 40 μl was placed in a well of the streptavidin plate and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. The ligation reaction was carefully removed with a multichannel pipette and the plate washed twice in 250 μl of freshly prepared wash buffer 1 (10 mM NaOH, 0.05%v/v Tween 20) and then twice in 250 μl of wash buffer 2 (0.1 M Tris-HCl pH7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05%v/v Tween 20).

40 μl of 75 mU/ml HSP-conjugated antifluorescein Ab (Roche 1 426 346) solution in 1% w/v BSA solution was placed in each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The plate was then washed three times in 250 μl of wash buffer 2. All buffer traces were removed by tapping the plate upside down on a paper towel and 100 μl of room-temperature TMB solution (Roche BM Blue Pod Substrate 1 484 281) added. At least 5 min were allowed for the colour to develop before plates were scored. Plates were read at 680 nm in a Molecular Devices Versa Max plate reader to provide a quantitative method of scoring which could be compared to the visual method of scoring to check reliability.

Results and Discussion

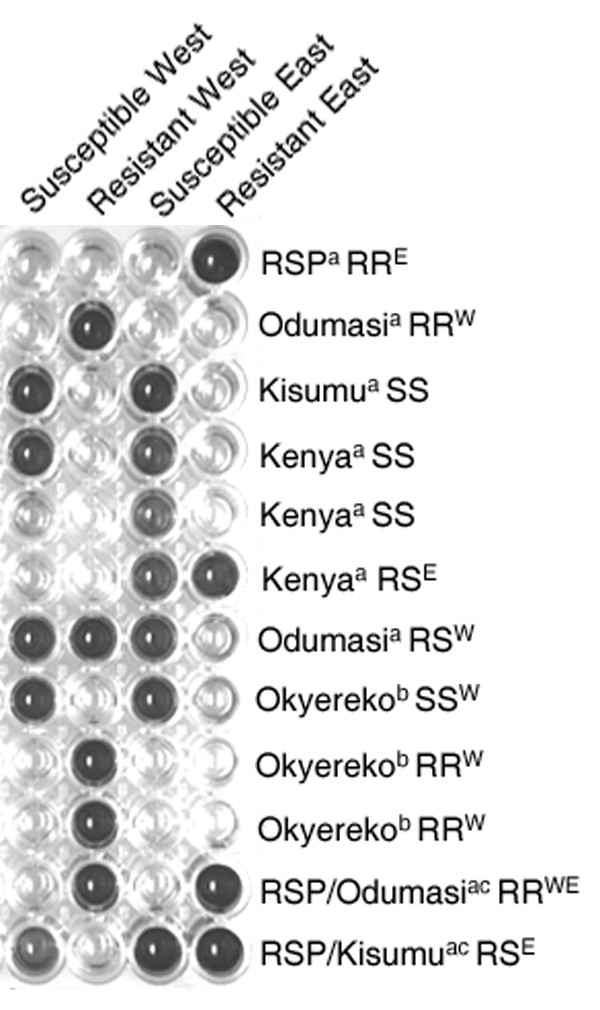

A schematic of the HOLA approach is given in Figure 1 and a photograph of the HOLA 96-well plate is shown in Figure 2. Susceptible individuals score positively for both the East and West African susceptibility tests although a somewhat weaker reaction may be seen in East African susceptible individuals for the West Susceptibility test. Resistant individuals show a positive colour change only for their specific kdr allele. Heterozygotes are easily distinguishable. The protocol presented here for kdr detection is reliable and gives unambiguous results (Table 1). Visual and colorimetric scoring results were always comparable (data not shown). A double-blind trial was carried out on 12 wild-caught specimens of An. gambiae from East Africa compared to the commonly used PCR multiplex approach. The genotype was unambiguously determined by the HOLA technique, whereas the PCR results were more difficult to interpret and often required a repeat reaction (Table 2). There was one discrepancy between the two approaches which was not resolved after repeated analyses (Specimen Kenya 3, Table 2). It is believed that the HOLA method gave the correct result since three HOLA repetitions were carried out on the sample which all scored the specimen as heterozygous. Contamination may be excluded as a cause of this discrepancy as HOLA reactions were performed before and after the PCR tests. Furthermore the kdr allele is rare in the Kenyan population [17] and so would be much more likely to occur more frequently in a heterozygous rather than homozygous state.

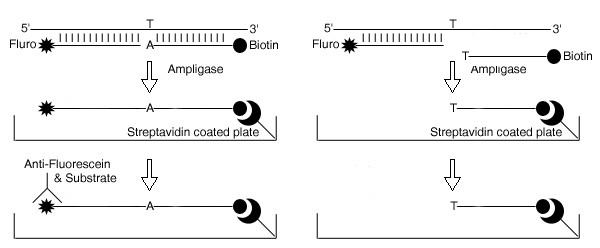

Figure 1.

Schematic of Hot Oligonucleotide Ligation Assay for West African Allele

Figure 2.

Photograph of HOLA plate, including DNA extraction method and expected results. Abbreviations: SS, homozygous susceptible. RR, homozygous resistant. RS, heterozygous. aLivak [14] extraction method bBallinger-Crabtree [15] extraction method cArtificially created heterozygote

Table 2.

Double blind trial of HOLA approach versus conventional PCR

| Specimen | HOLA | PCR 1e | PCR 2e |

| NK5a | SS | SS | SS |

| NK6 | SS | X | SS |

| NK7 | RR | RR | RR |

| NK8 | SS | SS | SS |

| Kenya 1b | SS | X | SS |

| Kenya 2 | SS | X | SS |

| Kenya 3 | RS | X | RR |

| Thyolo 7c | SS | SS | SS |

| Thyolo 33 | SS | SS | SS |

| Thyolo 34 | SS | X | SS |

| Thyolo 64 | SS | X | SS |

| Thyolo 75 | SS | X | SS |

| RSPd | RR | RR | RR |

aSpecimens labelled NK collected by Pie Muller, Ben Oloo, and Nadine Randle from Asembo, Kenya on 05/2004, DNA extracted by Ballinger-Crabtree method [15] on 09/2004. bSpecimens labelled Kenya collected by Pie Muller, Ben Oloo, and Nadine Randle from Asembo Bay, Kenya on 05/2004 DNA extracted by Livak method [14] on 08/2004. cSpecimens labelled Thyolo collected by Philimon Tambala and Bill Hawley from Thyolo, Malawi on 01/1995, DNA extracted by Ballinger-Crabtree method [15] on 09/1997. dSpecimen from RSP colony. Abbreviations: SS, homozygous susceptible. RR, homozygous resistant. RS, heterozygous. e Conditions for the PCR reactions were identical.

The HOLA method allows for over 40 samples to be screened on a single microtitre plate. As shown in Figure 2, the method works for a variety of DNA extraction techniques, on fresh and stored material. Although costs per reaction are slightly higher than for the traditional multiplex PCR, the greater reliability ensures that repeat reactions are unlikely to be required, reducing costs in the long term. In addition, since this technique dispenses with the need for gel electrophoresis apparatus there is a lower initial equipment outlay, greater comparative safety and greater ease of this technique, making the method ideal for field laboratories.

Conclusion

The HOLA method allows fresh and stored An. gambiae mosquitoes to be characterized for the East and West African kdr mutations. Homozygotes and heterozygotes can be easily distinguished using low cost equipment and a simple methodology which makes this technique suitable for use in resource-poor countries. In our hands the method is more reliable than the current multiplex PCR approach, less ambiguous and may be more sensitive for the detection of heterozygotes.

List of Abbreviations used

DNA – Deoxyribonucleic acid.

ELISA – Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

HOLA – Heated oligonucleotide ligation assay.

Kdr – Knock down resistance.

PCR – Polymerase chain reaction.

SNP – Single nucleotide polymorphism.

Authors' contributions

AL developed the HOLA method for the kdr mutation and drafted the manuscript. HR conceived of the study and participated in its design. NPR carried out the multiplex PCR. PJM and EDW helped draft the manuscript. WCB developed the HOLA technique. MJD participated in the design of the study and substantially helped draft the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Alexander Egyir-Yawson, Pie Muller, Ben Oloo, Bill Hawley, and Philimon Tambala for providing wild caught specimens. Funding for this work came from NIH grant U01 AI58542.

Contributor Information

Amy Lynd, Email: amylynd@liv.ac.uk.

Hilary Ranson, Email: hranson@liv.ac.uk.

P J McCall, Email: mccall@liv.ac.uk.

Nadine P Randle, Email: nadine.randle@liv.ac.uk.

William C Black, IV, Email: wcb4@lamar.colostate.edu.

Edward D Walker, Email: walker@msu.edu.

Martin J Donnelly, Email: m.j.donnelly@liv.ac.uk.

References

- Phillips-Howard PA, Nahlen BL, Kolczak MS, Hightower AW, ter Kuile FO, Alaii JA, Gimnig JE, Arudo J, Vulule JM, Odhacha A, Kachur SP, Schoute E, Rosen DH, Sexton JD, Oloo AJ, Hawley WA. Efficacy of permethrin-treated bed nets in the prevention of mortality in young children in an area of high perennial malaria transmission in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binka FN, Kubaje A, Adjuik M, Williams LA, Lengeler C, Maude GH, Armah GE, Kajihara B, Adiamah JH, Smith PG. Impact of permethrin impregnated bednets on child mortality in Kassena-Nankana district, Ghana: A randomized controlled trial. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1996;1:147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1996.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D' Alessandro U, Olaleye BO, McGuire W, Langerock P, Bennett S, Aikins MK, Thomson MC, Cham MK, Cham BA, Greenwood BM. Mortality and morbidity from malaria in Gambian children after introduction of an impregnated bednet program. Lancet. 1995;345:479–483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90582-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway J, Ranson H. Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Annu Rev Entomol. 2000;45:371–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elissa N, Mouchet J, Riviere F, Meunier JY, Yao K. Resistance of Anopheles gambiae to pyrethroids in Cote d'Ivoire. Annales de la Societe Belge de Medecine Tropicale. 1993;73:291–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulule JM, Beach RF, Ayieli FK, Roberts JM, Mount DL, Mwangi RW. Reduced susceptibilty of Anopheles gambiae to permethrin associated with the use of permethrin-impregnated bednets and curtains in Kenya. Med Vet Entomol. 1994;8:71–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1994.tb00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchet J. Agriculture and vector resistance. Insect Sci Applic. 1988;9:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Torres D, Chandre F, Williamson MS, Darriet F, Berge JB, Devonshire AL, Guillet P, Pasteur N, Pauron D. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol. 1998;7:179–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1998.72062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandre F, Darriet F, Duchon S, Finot L, Manguin S, Carnevale P, Guillet P. Modifications of pyrethroid effects associated with kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae. Med Vet Entomol. 2000;14:81–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandre F, Darrier F, Manga L, Akogbeto M, Faye O, Mouchet J, Guillet P. Status of pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambie sensu lato. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1999;77:230–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile G, Santolamazza F, Fanello C, Petrarca V, Caccone A, della Torre A. Variation in an intron sequence of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene correlates with genetic differentiation between Anopheles gambiae s.s. molecular forms. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13:371–377. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranson H, Jensen B, Vulule JM, Wang X, Hemingway J, Collins FH. Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:491–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway DJ, Roper C, Oduola AMJ, Arnot DE, Kremsner PG, Grobusch MP, Curtis CF, Greenwood BM. High recombination rate in natural populations of Plasmodium falciparum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 1999;96:4506–4511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ. Organization and mapping of a sequence on the Drosophila melanogaster X and Y chromosomes that is transcribed during spermatogenesis. Genetics. 1984;107:611–634. doi: 10.1093/genetics/107.4.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger-Crabtree ME, Black IV WC, Miller BP. Use of genetic polymorphisms detected by the Random-Amplified Polymorphic DNA Polymerase Chain Reaction (RAPD PCR) for differentiation and identification of Aedes aegypti subspecies and populations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:893–901. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:520–529. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stump AD, Atieli FK, Vulule JM, Besansky NJ. Dynamics of the pyrethroid knockdown resistance allele in western Kenyan populations of Anopheles gambiae in response to insecticide-treated bed net trials. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:591–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]