Abstract

Background:

Treatment for breast cancer can give rise to complications with important psychological impact. One change in patients regards body image. The aim of this research was to study the effect of a midwifery-based counseling support program on the body image of breast cancer survivors.

Materials and Methods:

In this randomized clinical trial, the study population was constituted by 80 breast cancer patients referred to Tuba Clinic in Sari, north of Iran, randomly assigned to two groups. Inclusion criteria included breast cancer diagnosis, mastectomy experience, age of 30 to 60 years, primary school education or higher, being married, and receiving hormone therapy. The Body Image Scale and Beck Depression Inventory were completed by intervention and control groups prior to the intervention and again afterwards. This program was implemented to the intervention group (two groups each consisting of 20 patients) for six weekly sessions, each lasting 90 minutes. The collected data were analyzed suing SPSS through Mann-Whitney U and Wilcoxon tests.

Results:

The results showed that the average age of participants in the intervention and control groups were 46.8 ± 6.85 and 48.9 ± 5.86, respectively. Body image scores in the intervention and control groups before the support program were respectively 21.82 ± 1.66 and 21.7 ± 1.48, and after the support program they were 7.05± 2.70 and 22.92 ±1.49, respectively. Therefore, the results indicate that the support program was effective in improving body image.

Conclusion:

This study showed that the support program had a positive effect on the body image of patients. Therefore, it is suggested that it should be used as an effective method for all breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: Breast cancer, body image, support program, counseling

Introduction

One of the most common diseases which have changed the lives of many people is breast cancer (Parizadeh et al., 2012). In fact, this disease is the first cancer among women cancers and the second leading cause of death among women around the world (Zare et al., 2011; Haghshenas, et al., 2016). However, advances in therapies such as the use of different types of surgeries, alternative and targeted therapies (Rezaei et al., 2016). has led to a 90% increase in the 5-year survival and to 80 percent survival after 10 years (Fobair et al., 2006). Despite this relatively good prognosis, therapies lead to side effects such as physical, sexual (Brandberg et al., 2008; Bakht et al., 2010; Kashani et al., 2014; Molavi Verdenjani et al., 2015). and psychological (depression, anxiety and fatigue) ones (Björneklett et al., 2013). and patients confront numerous concerns and a plethora of physical, emotional, and social experiences, such as shock, fear of recurrence, nausea, vomiting, changes in body function and changes in the role of the family (Cozaru et al., 2014; Khalili et al., 2015).

The important point is that the appearance and attractiveness of patients are impacted by the surgery and the course of treatment, and since physical attractiveness is an important variables for all people, its loss leads to patient’s disappointment, lower behavior control, and lower self-esteem (Heidari et al., 2015). For example, a study has shown that bilateral mastectomy has negative effects on body image (Brandberg et al., 2008). Therefore, the major concern of patients is losing one or both breasts and those who are candidate for this highly stressful phenomenon will have many social, physical, and sexual problems. In the social domain, due to the loss of the breast and feeling of embarrassment which follows it, the patient reduces her social activities. Physically and sexually, embarrassment with physical appearance and change of the patient’s body image pave the way for reduced pleasure and satisfaction with sexual relationships (Izadi-Ajirlo et al., 2013). These factors consequently pose problems in the relationship with the husband and the patient’s sexual activity (Izadi-Ajirlo et al., 2013; Rezaei et al., 2016) and these play a significant role in decreasing self-esteem and creating feeling of helplessness (Heidari et al., 2015). Hence, body image is associated with psychological dimensions (Parizadeh et al., 2012; Izadi-Ajirlo et al., 2013).

Although interventions such as phone-based support programs, group counseling and sex education programs have been conducted for patients with breast cancer (Heravi Karimoui, et al., 2006;Salonen et al., 2009; Lotfi Kashani et al., 2014). studies show these have had no effect on the improvement of patients’ body image (Jun et al., 2011; Lotfi Kashani et al., 2014). Moreover, a review of studies also indicates that in the course of the treatment, patients encounter various mental and physical problems. Therefore, providing information through support programs in the form of awareness raising, stress reduction, and coping and adaptation techniques can improve adherence to treatment, and compatibility with the circumstances to pave the way for the patient’s health and reduce the difficulties ahead (Fobair et al., 2006; Rahmani et al., 2010; Aguilar Cordero et al., 2015; Rezaei et al., 2016). Also awareness of appropriate coping strategies is built and a sense of support through empathic listening is created (Heravi Karimoui et al., 2006; Cozaru et al., 2014).

Furthermore, one of the fundamental rights of every human being is access to health care information and part of the responsibility of the health care providing system is to educate people on health care principles and to deal with patients’ problems (Nematollahzade et al., 2010). and since the midwives as service providers are associated with women throughout their lives, correct and sustained training and counseling can result in patients’ higher awareness and lower anxiety (Shobeyri et al., 2015). But the lack of relevant support programs as well as interventions by other professionals (Heravi Karimoui et al., 2006). were the impetus for us to study the impact of midwifery-based counseling support program on the body image of breast cancer patients. It is hoped that this research project can be a useful step to improve the health condition of these patients.

Materials and Methods

Design

This study is a randomized clinical trial which was conducted in Sari, north of Iran to investigate the impact of midwifery-based counseling support programs on the body image of breast cancer patients. It should be noted that this clinic receives breast cancer patients from all cities of Mazandaran province. This study with the design code of 2230 was registered in Iranian Registry for Clinical Trials with the Code of IRCT2016061928528N1.

Ethics

This study was also registered by the ethics committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences with the code of IR. Mazums. Rec. 2230-95.

Sample and Setting

Participants in the study were breast cancer patients from Touba Clinic in Sari. They were eligible women who met the inclusion criteria including 1) breast cancer development 2) being married 3) age of 30 to 60 years 4) primary level of education or higher 5) mastectomy experience and 6) undergoing hormone therapy. Women who were participating in other psychotherapy or counseling and training programs were excluded from the study because the other treatment program could have interfered with the body image of the patients. Moreover, other criteria which led to the exclusion of the patients from the study due the possible intervening factors included suffering from other cancers, severe psychiatric disorders (such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder reported by the patient or detected in the history records of the patient), taking certain medicine and suffering from severe depression based on Beck Inventory, undergoing alternative and complementary medicine interventions and acupuncture.

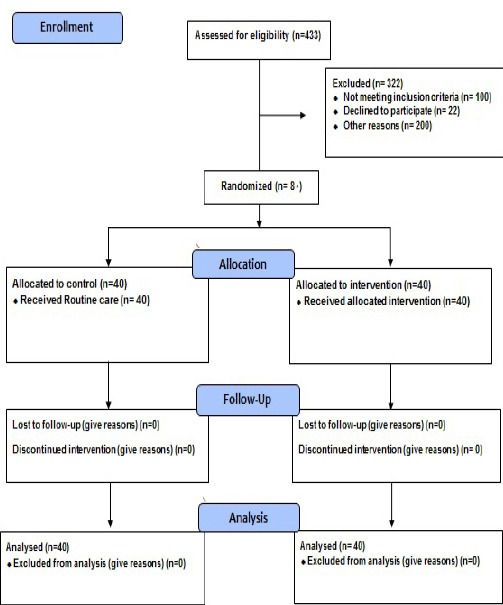

Based on the results of a pilot study, and using G-POWER software program, the sample size of each group was estimated to be 34 patients. The number was increased to 40 patients in each group to compensate for a possible 20% attrition. The selected patients were then randomly assigned to control (N= 40) and intervention (N = 40) groups. The significance level was set at 0.05 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort 2010 Flow Diagram

Procedures

The participants in the intervention group were informed of the time and number of sessions of the support program. They were asked to complete the Body Image Scale before the support program started. The scale was administered to the control groups and they were assured that a training session would also be held for them. The intervention was offered to the patients in two groups each with 20 breast cancer patients. Six weekly training sessions were held, each of which lasted for 90 minutes. The facilitator of the support program was a graduate student of midwifery counseling, who had undertaken elementary and advanced sex education courses. While the support program was held for the intervention group, the control group received the routine treatment.

After the sessions were over for the intervention group, the patients completed the scale again. Patients in the control group also completed the scale and they also received a training session. Data collection was completed on April 29, 2016.

Intervention

To offer the support program, the research team began to design, implement and assess the program for breast cancer patients. In the developed protocol, physical, sexual and psychological aspects were taken into account. These aspects include 1) information about breast cancer 2) information about sexual issues 3) information about body image and techniques to improve these variables (body image).

Also as part of the present support program, homework assignments were given to patients to consolidate and sustain the techniques. In fact, the study focused on communication skills, changing attitudes about body image, and muscle relaxation techniques. Each session patients received supplementary materials which were related to the topics of that session. This content of the program was approved by sexual and reproductive health specialists and psychiatrists. The main content of the support program included awareness of breast cancer (first session), stressors and symptoms (second session), familiarity with the genitals (third session), familiarity with changes (fourth session), familiarity with sexual issues (fifth session) and familiarity with improvement mechanisms and techniques (sixth session) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Content of Study Supportive Intervention for Patients with Breast Cancer

| Sessions | Topic | Content | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| One | Awareness of breast cancer | Cancer and its effect on patient’s life, relaxation technique, introducing calmness techniques | Lecturing-Discussion |

| Two | Stressors and Symptoms | Breast cancer stressors, teaching stress symptoms, introducing stress coping strategies | Lecturing-Discussion |

| Three | Familiarity with genitals | Information on genitals, Presenting information on breast, introducing side effects of cancer on sexual relationship | Lecturing-Discussion |

| Four | Familiarity with changes | Teaching appropriate strategies to cope with cancer complications, introducing strategies to cope with changes, strategies to establish effective relationship | Lecturing-Discussion |

| Five | Familiarity with sexual problems | methods of sustaining health along with treatment | Lecturing-Discussion |

| Six | Familiarity with solutions | teaching improving techniques related to body image | Lecturing-Discussion |

Measures

Data collection instruments in this study were one checklist and one scale and one inventory.

Check list

To determine the eligibility of patients for entry into the sample, a checklist was used. The checklist included two tables of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed through reviewing the related literature. The variables included demographic data, including age, education, duration of married life, number of children, housing status, household members, occupation, monthly income, menopausal status, disease duration, and number of chemotherapies, frequency of radiotherapy and family history of breast cancer (Nurachmah, 1998, Heravi Karimoui, Pourdehghan et al. 2006, Bahrami and Farzi, 2014).

Beck Depression Inventory

Beck Depression Inventory was developed as a tool to assess severity and symptoms of depression. The inventory has 21 items on a four-point Likert scale which ranges from 0 to 3. Each item consists of four statements. The scores of 1-10 mean natural, 11-16 mean a little depressed, 17-20 mean requiring counseling, 21-30 mean relatively depressed, 31-40 mean severe depression and more than 40 mean too depressed. Beck Depression Inventory indicates that people’s moods and it was validated by Mohammad Khani and colleagues in 1392 on 354 patients with severe depression. The reliability coefficient for inventory was 0.93 (Stefan-Dabson, Mohammadkhani et al., 2007).

Body image Scale

The scale has 10 items on a four-point Likert scale ranging from never (0), to very low (1), partly (2) and very high (3). The total score on the scale ranges from 0 to 30 (27). Body image scale was developed to assess postoperative body image in breast cancer patients. The basic version of the scale was validated by Farsani and colleagues on 200 breast cancer patients who referred to Saba specialized clinic and Ayatollah Kashani Hospital in Isfahan and Cronbach’s alpha of.70 was reported for the scale (Farsani et al., 2015).

Analysis

Since the study includes an independent variable (support program) and a dependent variable (body image), mean, standard deviation, median and percentage were used to describe the variables. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the assumption of normality of the data for parametric tests. Then to analyze the data, analytical statistics such as Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon tests were used. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the intervention and control groups are displayed in Table 2. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, stage of treatment, education, length of the married life, occupation, number of chemotherapies, and number of children. The mean age of the intervention group was 46.77± 6.85 and that of the control group was 48.92±5.86.

Table 2.

Distribution of Breast Cancer Patients Based on Demographic Characteristics and for the Intervention and Control Groups in 2016

| Support Program(n=40) | Routine care(n= 40) | Test results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variable | Number of patients | Percentage | Number of patients | Percentage | |

| ± Menopause | |||||

| Menopause | 34 | 85 | 32 | 80 | |

| Non-menopause | 6 | 15 | 8 | 20 | P= 0.556 |

| ±Length of the disease (year) | 20.65 | 10.01 | 22.13 | 7.76 | P= 0.464 |

| ± Number of chemotherapy | 7.75 | 2.56 | 8.25 | 1.89 | P= 0.323 |

| ± Number of radiotherapy | 25.48 | 7.34 | 26.05 | 3.31 | P= 0.653 |

Results of body image

Mean score of body image of the intervention group before the intervention was 21.82 ± 1.66 and after the intervention it was 7.05 ± 2.70. In the control group, the mean body image score before receiving routine care was 21.70 ± 1.48 and after receiving routine care it was 22.92±1.49. Mann-Whitney U test showed that after the support program there was a significant difference between the mean body image scores of the intervention group and the control group, and patients in the intervention group had a better body image than the control group (p = 0.000) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of Breast Cancer Patients Based on Body Image for Intervention and Control Groups before and after Support Program Intervention

| Breast cancer patients | Body Image | Test result | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | ||||||

| Mean | Percentage | Median | Mean | Percentage | Median | ||

| Before the intervention | 21.82 | 1.66 | 21.5 | 21.7 | 1.48 | 22 | P= 0.965 |

| After the intervention | 7.05 | 2.7 | 7.0 | 22.92 | 1.49 | 23 | P= 0.000 |

Discussion

This study investigated the impact of the counseling support program on the body image of breast cancer patients. The program was implemented in six weekly sessions each lasting for 90 minutes and the results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed that the mean scores of body image were significantly different before and after the intervention. Moreover, the results of Wilcoxon rank test showed a significant difference before and after the support program both for the intervention and control groups.

This study aimed to raise the awareness of the patients and to train them on the skills related to body image, and therefore to change the negative body image of the patients. The results showed that breast cancer patients in the intervention group had a better body image compared to the control group. In fact, the presence of the disease and the physical complications that follow it, result in concern, fear and psychological problems. Therefore, it seems useful to have interventions that can inform patients of the disease course, its complications and more importantly, of practical strategies because persistence of this situation paves the way for interpersonal problems.

Therefore, this study attempts to provide useful information in this regard. Moreover, the results of this study are consistent with the findings of Heravi et al., (2006) And Salonen et al., (2009). In fact, through providing information on the disease background, problems in the course of treatment and techniques for solving these problems, these studies attempted to help patients have better body images and the results of these studies also showed that the intervention groups had improved compared with the control groups. It should be noted that this intervention feature was present in the current study too. The key to the effectiveness of interventions was the attempt to identify individual strengths and to improve patients’ awareness and to train them on appropriate skills, because raising awareness of the problem and its related factors leads to the use of appropriate skill to solve it (Geiger et al., 1999; Ganz et al., 2011). In this study, the use of suggested techniques also helped the patients to take action for solving their problems and this was effective in improving their bod image. Therefore, the results of this study were in line with the findings of Lotfi et al., (2014) And Izadi et al., (2013).

The important thing is that in the course of disease and treatment, problems associated with the bodies of the patients have effects on the psyche and spirit of the patients too (Vaziri et al., 2014). Therefore, breast cancer is strongly associated with psychological distress and the most common psychiatric disease is anxiety and depression (Ursaru et al., 2014). So the researchers considered patients without sign of depression due to problems associated with depression and its effects on the patient. Therefore same condition in two group of intervention and control is considered too. In addition, one of the inclusion criteria was absence of psychiatric disorders such as bipolar, schizophrenia. This variable was assessed based on past medical history or the patient report and marched in intervention and control group. Therefore, in this study the techniques related to change of appearance and muscle relaxation were presented to help reduce patients’ stress. This aim was in line with what Saski and Shariati intended (Duijts et al., 2009; Shariati et al., 2010). In fact doing muscle exercise has positive effects on patients’ tension and stress and it paves the ground for patients to solve the related problems too. Because patients often have a deadly image of cancer and the major concern of breast cancer patients is the amputation of the breast which leads to consequences such as deformation and sexual dysfunction and it becomes a factor for stress and its concomitant problems (Izadi-Ajirlo et al., 2013). Therefore, support programs which in the initial stage support the patients through empathic listening and in later stages create an atmosphere for supporting and providing information, problem solving and presenting techniques can lead to higher awareness of patients, their self-care and their increased abilities to cope with the problems (Geiger et al., 1999; Cozaru et al., 2014; Fernandes et al., 2014).

Since breast cancer patients need physical and emotional support, holding training-supporting classes seems to be useful in meeting these needs of the patients (Rahmani et al., 2010). The reason is that as studies have shown, patients might have some questions regarding the disease but they might give up inquiring about them due to shame or short time of the health care team. Therefore, support programs provide a condition for the patients to ask their questions in an atmosphere far from shame and concern, and then to take action to solve their problems. Because of the long treatment process, there needs to be more contacts with the patients to provide the conditions to answer their questions and to solve their problems. In fact, this was done in the present study and one of the researchers through attendance in the sessions and telephone contact attempted to answer patients’ questions. However, the results of this study were not consistent with the findings of Björneklett et al., (2013). Jun et al., (2011). Fadaei et al., (2011) and Speck et al., (2010). Apparently, the reason for this difference is that in these studies the focus was not on body image and the patients were not followed up either during meetings nor over the programs (Jun et al., 2011; Björneklett et al., 2013). However, in our study, one session was specifically devoted to body image and throughout the support program, the researcher was available to answer patients’ phone calls and she replied to their on the implementation of the techniques and on the created problems.

Since one of the requirements of compatibility and problem solving is the sustained practice of techniques, another measure which was taken in this study was to give patients homework assignments at the end of each session. These assignments helped the patients to pay more attention to the presented materials and to the training techniques. Moreover, in each of the six weekly support sessions, some minutes were devoted to reviewing previous session content. In fact, this technique helped patients to listen to the materials for the second time and keep the important points in mind. Another reason for the discrepancy between the findings of this study and those of the previously cited studies is the length of the sessions and the interval between the sessions (Björneklett et al., 2013). In this study, six weekly sessions were held and this cohesion seems to lead to patients’ increased awareness and it supported them in solving their problems. This ultimately influenced the body image scores of the patients.

The results of studies have shown that for women, breast is an aspect of identity, attractiveness and femininity and losing it can have various physical, psychological and social side effects. In the physical and psychological aspects, losing a breast is followed by concerns about body image, which leads to a reduction in social activities, decreased sexual pleasure and satisfaction, and embarrassment with physical appearance (Heravi Karimoui et al., 2006). Therefore, support programs through appropriate support, can reduce stress and raise awareness of the disease. In fact, the presence of support groups and similar programs can be an opportunity for the patients to share their experiences, identify risk factors, improve their abilities to cope with stress and make positive changes (Cozaru et al., 2014) and this was actualized in this study.

In fact, the support program developed in this study can help breast cancer patients in the diagnosis, treatment and complications of the disease so that fewer problems are posed to them. Finally, since in the first stage of the disease, the major concern of the patients is body image problems, only women with breast cancer entered into the present study.

The time of outcome assessment was the shortcoming of this study. The authors suggested long term assessment of body image changes in another study.

In conclusion, this study investigated the impact of support programs on body image of breast cancer patients in six consequent weeks and the results showed an improvement of the body image in breast cancer patients. This program was the first midwifery-based counseling intervention for patients with breast cancer in Mazandaran province. The counseling midwife as a facilitator has two important roles: as a midwife who is familiar with the physical problems such as sexual problems, negative self-image and body image and as a counselor who through different skills paves the way for problem solving. Therefore, integration of these two fields increases the person’s ability and paves the ground for the better realization of the aims.

It is hoped that this study can be a groundbreaking for future research, and counseling support programs can find a place in therapeutic programs so that they can be used for a longer time for both the patients and their husbands.

Strengths of the study

In the present study, the structure of the sessions was planned based on a protocol which was developed by the research team. The number of sessions and the objectives of each session were followed based on the provided protocol. Moreover, for the sake of homogenization, patients entered the study during hormone therapy.

Study limitations

Since due to technological reasons the telephone numbers of cities in the province had changed, it was difficult to contact some patients and therefore some could not attend the sessions.

Suggestion for further research

Since the study aimed to be conducted with homogenous groups, the entry requirement into the study were based on the type of therapy (hormone therapy). So, the following are suggested as areas for further research by other researchers:

The effect of counseling support programs on the body image of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients.

The effect of counseling support programs on the body image of single breast cancer patients.

The effect of counseling support programs on the body image of breast cancer patients during chemotherapy.

Registration of the clinical trial

This study was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials with the code of IRCT2016061928528N1.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari Cancer Center, and Center for Research on Sexual issues for their close collaboration with the research team. We also extend our sincere appreciation to the dear patients who patiently attended the sessions and their attendance aimed to help push the borders of knowledge back.

References

- Aguilar CMJ, Mur VN, Neri SM, et al. Breast cancer and body image as a prognostic factor of depression:a case study in México City. Nutr Hosp. 2015;31:371–9. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.31.1.7863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami M, Farzi S. The effect of a supportive educational program based on COPE model on caring burden and quality of life in family caregivers of women with breast cancer. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19:119–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakht S, Najafi S. Body image and sexual dysfunctions:comparison between breast cancer patients and healthy women. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:1493–7. [Google Scholar]

- Björneklett HG, Rosenblad A, Lindemalm CH, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized study of support group intervention in women with primary breast cancer. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:346–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandberg Y, Sandelin K, Erikson S, et al. Psychological reactions, quality of life, and body image after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women at high risk for breast cancer:A prospective 1-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3943–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozaru GC, Papari AC, Sandu ML. The Effects of psycho-education and counselling for women suffering from breast cancer in support groups. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;128:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Duijts SF, Oldenburg HAS, van Beurden M, Aaronson NK. Cognitive behavioral therapy and physical exercise for climacteric symptoms in breast cancer patients experiencing treatment-induced menopause:design of a multicenter trial. BMC Women’s Health. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadaei S, Janighorban M, Mehrabi T. Effects of cognitive behavioral counseling on body Image following mastectomy. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:1047–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsani KZ, Rajabi GH, Fadaee DCH, Jelodari A. Evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian version scale body image in patients with breast cancer. Iran J Breast Dis. 2015;8:66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes AF, Cruz A, Moreira C, Conceic M, Silva T. Social support provided to women undergoing breast cancer treatment:A study review. Adv Breast Cancer Res. 2014;2014:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, et al. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:579–94. doi: 10.1002/pon.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Bower JE, Belin TR. Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1101–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger A, Mullen ES, Sloman PA, Edgerton BW, Petitti DB. Evaluation of a breast cancer patient information and support program. Eff Clin Pract. 1999;3:157–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghshenas MR, Mousavi T, Moosazadeh M, Afshari M. Human papillomavirus and breast cancer in Iran:a meta-analysis. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2016;19:231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari M, Ghodusi M, Shahbazi S. Correlation between body esteem and hope in patients with breast cancer after mastectomy. J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2015;4:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Heravi-Karimoui M, Pourdehghan M, Jadid-Milani M, Foroutan SK, Aieen F. Study of the effects of group counseling on quality of sexual life of patients with breast cancer under chemotherapy at Imam Khomeini Hospital. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2006;16:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Izadi-Ajirlo A, Bahmani B, Ghanbari-Motlagh A. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral group intervention on body image improving and increasing self-esteem in women with breast cancer after mastectomy. Quarterly J Rehabilitation. 2013;13:72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jun EY, Kim S, Chang SB, et al. The effect of a sexual life reframing program on marital intimacy, body image, and sexual function among breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:142–9. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f1ab7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashani FL, Vaziri SH, Akbari MS, Jamshidi Far Z, Smaeeli Far N. Sexual skills, Sexual satisfaction and body image in women with breast cancer. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;159:206–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khalili R, Bagheri-Nesami M, Janbabai GH, Nikkhah A. Lifestyle in Iranian patients with breast cancer. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:XC06. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13954.6233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotfi-Kashani F, Vaziri SH, Hajizadeh Z. Sexual skills training, body image and sexual function in breast cancer. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;159:288–92. [Google Scholar]

- Molavi-Verdenjani A, Hekmat KH, Afshari P, Hosseini MS. Evaluation of couples sexual functio and satisfaction after mastectomy. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2015;17:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nematollahzade M, Maasoumi R, Lamyian M. Study of women’s attitude and sexual function during pregnancy. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2010;10:241–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nurachmah E. The effect of participation in a support group on body image, intimacy, and self-efficacy of Indonesian women with breast cancer. Faculty of the school of nursing of the catholic University Of America. 1998:1–217. [Google Scholar]

- Parizadeh H, Hasan Abadi H, Mashhadi A, Taghizadeh kermani A. Comparison the effectiveness of existentioal therapy and reality group therapy on problem solving body image of women with mastectomy. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2012;15:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani A, Safavi SH, Jafarpoor M, Merghati-Khoei ES. The relation of sexual satisfaction and demographic factors. Iran J Nurs Res. 2010;23:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei M, Elyasi F, Janbabai GH, Moosazadeh M, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Factors influencing body image in women with breast cancer:A comprehensive literature review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18:1–9. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.39465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei M, Elyasi F, Janbabai GH, Moosazadeh M, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Improveing the health of p breast cancer survivors:A clinical Guideline with an emphasis on sexual health (for the patients and families), practical techniques, Norozi and Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2016:1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen P, Tarkka MT, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, et al. Telephone intervention and quality of life in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:177–90. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819b5b65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariati A, Salehi M, Ansari M, Latifi SM. Survey the effect of Benson relaxation intervention on quality of life (QOL) in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Sci Med J Ahwaz Jundishapur Univ Med Sci. 2010;9:625–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shobeyri F, Nikravesh A, Masoumi SZ, et al. Effect of exercise counseling on functional scales quality of life in women with breast cancer. Edu Commun Health. 2015;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Speck RM, Gross CR, Hormes JM, et al. Changes in the body image and relationship scale following a one-year strength training trial for breast cancer survivors with or at risk for lymphedema. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:421–30. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan-Dabson K, Mohammadkhani P, Massah-Choulabi O. Psychometrics characteristic of beck depression inventory-II in patients with magor depressive disorder. Quarterly J Rehabil. 2007;8:80–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ursaru M, Crumpei I, Crumpei G. Quality of life and religious coping in women with breast cancer. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;114:322–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri S, Lotfi-Kashani F, Akbari MS, Ghorbani-Ashin Y. Comparing the motherhood and spouse role in women with breast cancer and healthy women. Iran J Breast Dis. 2014;7:76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zare M, Zakiani SH, Rezaee A, Najari A. Designing and establishment of information and treatment management system of breast cancer in Iran. Iran J Breast Dis. 2011;4:35–41. [Google Scholar]