Abstract

Background

Presbyopia is an age related loss of accommodation that results in the inability to focus at near distances. Few population-based studies exist on the prevalence of presbyopia among people living in developing countries.

Aim

To determine the prevalence of presbyopia, presbyopia correction coverage and identify barriers to spectacle usage in individuals aged 35years and above.

Design

Cross sectional descriptive survey

Setting

Esie, a rural community in Kwara State, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

Four hundred and four subjects with best corrected distance vision ≥20/60 were enrolled into the study by a multistage sampling procedure. Distance and near vision testing and near refraction (for those with presenting near VA < N8 at 40cm) were carried out. Interviewer administered structured questionnaires were used to collect subjects’ information.

Results

Three hundred and thirty five subjects were included while 24 subjects were not available for examination and 45 subjects excluded based on the visual acuity cut off point. The age range was 35 to 100 years, with a mean age of 57±12.1years. The prevalence of presbyopia was 59.7%. Presbyopia correction coverage was 46.5%. Increasing age was found to be significantly associated with presbyopia, while gender, occupation and educational level were not. Skilled workers, retired persons and those with at least a secondary education were more likely to have glasses than others. The commonest barrier to obtaining near vision glasses was lack of money.

Conclusion

Presbyopia is a major burden and cause of ocular morbidity in this rural community. Cost is the commonest barrier to obtaining near vision spectacles. Increasing the availability of affordable spectacles will go a long way to overcome this.

Keywords: Presbyopia, Increasing age, Cost of spectacles, Nigeria

Introduction

Presbyopia is an age-related loss of accommodation that results in inability to focus at near distances due to the natural decline of the amplitude of accommodation with age. Correction of this is achieved by the use of a supplementary convex lens to enable the individual achieve comfortable near vision. Lifelong growth of the lens is currently thought to be the primary causal factor in the development of presbyopia1. Age, high ambient temperature, female gender and hypermetropia are major risk factors for the early onset and development of presbyopia2-5.

Few population-based studies exist on the prevalence of presbyopia in developing countries as most studies of refractive error in our environment have been limited to distance vision. This is because presbyopia is presumed to be unimportant in places where reading and writing are not primarily important functions3. There is scant research evidence from the available studies to substantiate this assumption6. Hence, little attention has been paid to presbyopia in the developing world where literacy rates are low.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated in 2002 that about 153million are visually impaired from uncorrected refractive errors (i.e. presenting with visual acuity (VA) <6/18 in the better eye, excluding presbyopia), 8 million of whom are blind8. A 2005 estimate put the number of presbyopic population worldwide at 1.04 billion people, of whom 517 million (49.7%) were uncorrected9. Clinic and population based studies done locally in Nigeria showed a high prevalence of presbyopia. Ashaye et al reported that presbyopia was one of the most common ocular problems seen among staff aged 30 years and above in a Federal Institution based in Lagos, Nigeria10. A population based study of presbyopia in Gwagwalada, Nigeria, by Muhammad et al5, among adults 40 years and older found a prevalence of 53.4%. Female gender and increasing age were associated with presbyopia, and presbyopia was more severe in females5. Population and clinic based studies among other African populations reported a prevalence of presbyopia between 48% and 65%3, 11, 12. In other parts of the world, prevalence values range from 55.3% (South India)13, to 68.2% in Finland14.

Varying rates of presbyopia correction have been found across the globe, from 21% in urban areas like Gwagwalada in Nigeria5, 17.6% in Zanzibar15, 30% in Andra Pradesh, India13 and 51.5% in China16. As the elderly population in developing countries increases and becomes more literate15, more people will require presbyopia screening and optical services. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of presbyopia, presbyopia correction coverage and barriers to spectacle usage in individuals 35years and above in Esie, a rural community in Kwara State, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

The study was a population-based cross sectional descriptive survey of people aged 35 years and older carried out in Esie, in Irepodun Local Government Area of Kwara State, Nigeria, between April and June 2013. Esie is a rural community located in the north-central geo-political zone of Nigeria. The population of Esie in 2012 projected from the 2006 census at an annual growth rate of 2.3% was estimated at 6,72717. The University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital (UITH), Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria, runs a comprehensive health centre in the study community which provides ophthalmic services with ophthalmologists in training, ophthalmic nurses and community health extension workers trained in providing primary eye care services under the supervision of consultants.

Persons resident in the community for at least 3 months prior to the study who consented to participate in the study and with best corrected visual acuity(VA) better than or equal to 20/60 were included in the study. An existing household numbering used for primary health care which grouped households in Esie into sixty compounds was used to select the 335 study participants. A multi-stage random sampling procedure was performed. In the first stage, the names of the sixty compounds were written on pieces of paper, rolled up and one name was removed randomly to serve as the index compound. Thereafter, with a sampling interval of 3, every 3rd compound was selected using a systematic random sampling technique. Twenty of the listed sixty compounds were thus selected. In the second stage, the index household within each compound was selected using bottle spinning. Using the random walk method, adults aged 35 years and above were recruited into the study from the households in the direction indicated by the spun bottle until twenty adults had been recruited. This was done in all the pre-selected compounds to recruit an adequate number of participants into the study. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of UITH. Informed and written consent was obtained from all subjects enlisted.

An Ophthalmologist performed anterior and posterior segment examination, distance and near refraction and referral of subjects that needed such. The ophthalmic nurse (along with one of the community health extension workers) carried out enumeration of subjects and visual acuity testing. The other two community workers administered the questionnaires.

Distance VA was measured using either a Snellen tumbling illiterate “E” chart or a literate chart depending on the subject’s literacy level at 6 meters in ambient outdoor illumination under a shade with the subject’s current corrective lens, if any, in place. Subjects with presenting acuity of 20/20 were assumed emmetropic for distance and tested for near acuity. Subjective distance refraction was then done for subjects with visual acuity worse than 20/20 after demonstrating improvement of at least one line when tested with a pinhole. The refraction was conducted using a trial lens set with the addition of plus or minus lenses in half dioptric increments until the subject was able to read 20/20 or showed no further improvement with additional lenses. Astigmatism was not corrected for to reduce testing time. Visual acuity was tested in each eye at a time.

Presenting near vision was then tested using a near vision LogMAR “E” chart or a Jaeger’s chart in English or any of the major Nigerian languages with ambient light. A string was attached to the near vision chart with a loop that was worn around the subject’s neck to ensure a measurement distance of 40cm from the eyes. Visual acuity was measured binocularly and recorded as the smallest line read correctly. After near VA measurement, a pen-torch was used to examine the anterior segment and an ophthalmoscope was used to examine the posterior segment without dilation of the pupil, of all subjects. Those whose distance VA did not improve to up to 6/18 with a pinhole were examined to exclude visually significant ocular disease, such as cataract and retinal disease. Such subjects were thereafter referred to the eye clinic within the community.

Near refraction was done using spherical plus lenses added in increments of 0.5 dioptre until the subject was able to read N8 or no further improvement occurred. Those with uncorrected presbyopia were assisted to obtain their glasses through the eye clinic of UITH in the community. The degree of presbyopia was determined by the minimum amount of added plus lenses needed to achieve maximum improvement in line read (to the N8 end point).

Presbyopia correction coverage (PCC) was calculated as PCC (%) = 100 x (number with presbyopia need met)/([number with presbyopia need met] + [number with presbyopia need unmet])16.

Interviewer administered structured questionnaires were used to collect all biodata, information on previous use of spectacles and barriers to spectacle use. The questionnaire was translated into Yoruba which is the major language spoken in the community to ensure validity. The data obtained was entered into a computer using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20 for analysis. Prevalence rates were calculated for presbyopia. Chi-square was used to test for significance. Statistical significance was said to have been achieved at p value equal to or less than 0.05.

Results

A total of 335 subjects were examined with age range of 35 to 100years. The mean age of the participants was 57 ± 12.1 years (Table 1). There were 100 males and 235 females with male/female ratio of 1:2.4.

Table 1: Age distribution of subjects.

| Age Distribution(Years) | Frequency | Percentage |

| 35-44 | 52 | 15.5 |

| 45-54 | 100 | 29.8 |

| 55-64 | 87 | 26.0 |

| 65-74 | 66 | 19.7 |

| >75 | 30 | 9.0 |

| Total | 335 | 100.0 |

| Mean +/- SD = 57.04+/-12.15 | ||

Most subjects were married (241; 71.9 %), 18 (5.4%) were single, 4 (1.2%) were divorced while 72 (21.5%) were widowed. Subjects were predominantly Yoruba – 316, (94.3%), 14 were Igbo (4.2%), one Hausa (0.3%) and others, four (1.2%). Of the subjects, 250 (75.2%) were Christians, 81 (24.2%) were Muslims while 2 (0.6%) were adherents of traditional religion.

Table 2 shows the educational status of the subjects with about a third without any formal education. Most of the subjects were manual workers (159; 47.5%), while the rest were either skilled workers (76; 22.7%), unemployed (34; 10.1%), housewives (26; 7.8%) or retirees (40; 11.9%).

Table 2: Level of Education of Subjects.

| Level of education | Frequency | Percentage |

| No formal Education | 102 | 30.4 |

| Primary | 106 | 31.6 |

| Secondary | 50 | 14.9 |

| Post Secondary | 77 | 23.0 |

| Total | 335 | 100.0 |

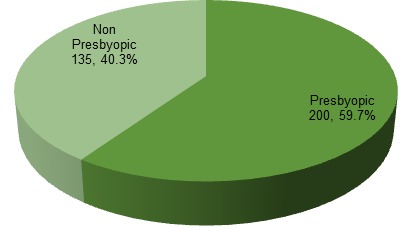

The prevalence of presbyopia (presenting near VA < N8) in this sample was 59.7% (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Prevalence of presbyopia.

Table 3 shows the association of age, gender, educational level and occupation with being presbyopic. Age was found to be significantly associated with presbyopia (chi square 11.366; p value 0.023). A larger proportion of subjects in the age groups 35-44 and 65-74 were presbyopic, while more individuals in the other age groups were nonpresbyopic. None of gender, level of education or occupation was found to be significantly associated with presbyopia in this sample. ( p values for gender – 0.197; occupation 0.082; level of education 0.752)

Table 3. Comparison of presbyopic and non-presbyopic subjects in terms of age, gender, occupation and educational level.

| Presbyopic (%) | Nonpresbyopic(%) | Total(%) | Chi square(X2) | P value | |

| Age group | 11.366 | 0.023 | |||

| <45 | 30(22.2) | 22(11.0) | 52(15.5) | ||

| 45-54 | 30(22.2) | 70(35.0) | 100(29.9) | ||

| 55-64 | 34(25.2) | 53(26.5) | 87(26.0) | ||

| 65-74 | 29(21.5) | 37(18.5) | 66(19.7) | ||

| >75 | 12(8.9) | 18(9.0) | 30(9.0) | ||

| Gender | 1.663 | ||||

| Male | 35(25.9) | 65(32.5) | 100(29.9) | 0.197 | |

| Female | 100(74.1) | 135(67.5) | 235(70.1) | ||

| Occupation | 8.276 | ||||

| Unemployed | 11(8.1) | 23(11.5) | 34(10.1) | ||

| Housewife | 7(5.2) | 19(9.5) | 26(7.8) | ||

| Manual workers | 76(56.3) | 83(41.5) | 159(47.5) | 0.082 | |

| Skilled workers | 25(18.5) | 51(25.5) | 76(22.7) | ||

| Retirees | 16(11.9) | 24(12.0) | 40(11.9) | ||

| Level of education | 1.203 | 0.752 | |||

| No formal | 44(32.6) | 58(29.0) | 102(30.4) | ||

| Primary | 39(28.9) | 67(33.5) | 106(31.6) | ||

| Secondary | 19(14.1) | 31(15.5) | 50(14.9) | ||

| Post Secondary | 33(24.4) | 44() | 77(23.0) |

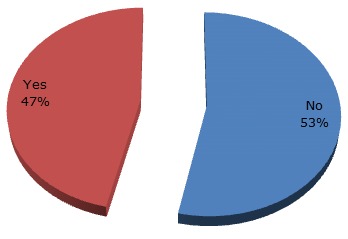

The number of presbyopic subjects who had glasses for their near vision problem (met need) is shown in Fig. 2 The presbyopia correction coverage (PCC) was 46.5%.

Fig. 2: Presbyopia correction coverage.

Table 4 shows the factors found to be associated with meeting the presbyopic need of subjects. Occupation was significantly associated with met need, with more skilled and retired people having glasses compared with those who did not, while fewer manual workers and housewives had glasses (chi square 21.501; p value <0.0001). Level of education was also found to be significantly associated with owning spectacles ( chi square 23.505; p value <0.0001). 39.3% of those without glasses had no formal education, while 35.5% of those that had glasses had post secondary education. However, age and gender were not significantly associated with having presbyopic need met.

Table 4: Relationship of age, gender, occupation and level of education with owning near vision glasses.

| Glasses for near vision problem | Total(%) | Chi square | P value | ||

| No(%) | Yes(%) | ||||

| Age group | 4.588 | 0.332 | |||

| <45 | 13 (12.1) | 9 (9.7) | 22 (11.0) | ||

| 45-54 | 42 (39.3) | 28 (30.1) | 70 (35.0) | ||

| 55-64 | 29 (27.1) | 24 (25.8) | 53 (26.5) | ||

| 65-74 | 15 (14.0) | 22 (23.7) | 37 (18.5) | ||

| >75 | 8 (7.5) | 10 (10.8) | 18 (9.0) | ||

| Gender | 1.306 | 0.253 | |||

| Male | 31 (29.0) | 34 (36.6) | 65 (32.5) | ||

| Female | 76 (71.0) | 59 (63.4) | 135 (67.5) | ||

| Occupation | 21.501 | <0.0001 | |||

| Unemployed | 10 (9.3) | 13 (14.0) | 23 (11.5) | ||

| Housewife | 14 (13.1) | 5 (5.4) | 19 (9.5) | ||

| Manual | 56 (52.3) | 27 (29.0) | 83 (41.5) | ||

| Skilled | 21 (19.6) | 30 (32.3) | 51 (25.5) | ||

| Retired | 6 (5.6) | 18 (19.4) | 24 (12.0) | ||

| Level of education | 23.505 | <0.0001 | |||

| No formal Education | 42 (39.3) | 16 (17.2) | 58 (29.0) | ||

| Primary | 35 (32.7) | 32 (34.4) | 67 (33.5) | ||

| Secondary | 19 (17.8) | 12 (12.9) | 31 (15.5) | ||

| Post Secondary | 11 (10.3) | 33 (35.5) | 44 (22.0) | ||

| Total | 107 (100.0) | 93 (100.0) | 200(100.0) | ||

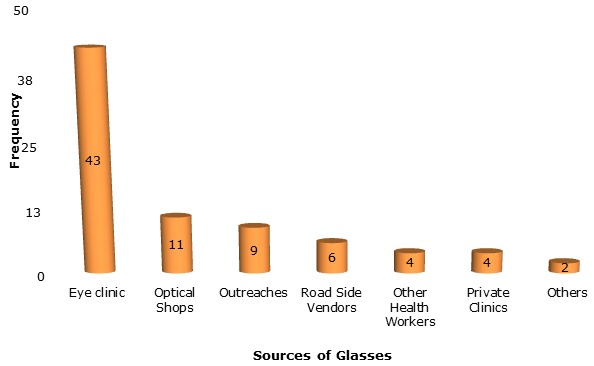

Most subjects that had glasses obtained them from an eye clinic (43; 54.4%). Eleven (13.9%) subjects got their glasses from optical shops, while other sources included roadside vendors, ophthalmic outreaches or other healthcare workers.

The commonest barrier cited by those that had no spectacles for their near vision problem was lack of money (39.3%, see Table 5); followed by not being aware of their near vision problem as they had no difficulty with near work.

Table 5: Barriers to obtaining near vision spectacles.

| Barriers | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| No money | 42 | 39.3 |

| Not aware | 25 | 23.4 |

| Not a priority | 20 | 18.7 |

| Services are too far | 10 | 9.3 |

| Normal ageing process | 8 | 7.5 |

| Do not know where to get it | 1 | 0.9 |

| No one to accompany | 1 | 0.9 |

| Total | 107 | 100.0 |

Fig. 3: Source of presbyopic glasses.

Discussion

The study had a high participation rate of 94.1%, higher than the 83% obtained in Tanzania by Burke et al3 and higher than the 78% found in Gwagwalada, Nigeria by Muhammad et al5. There were far more females than males in this study population; with a M:F ratio of 1:2.4. This could be accounted for by the fact that this study was done in a small rural community, with increased rural-urban migration by males for better economic opportunities. The mean age of participants was 57 years, higher than the 52.5 years obtained by Muhammad5. This can also be attributable to presence of a higher population of younger people in more urban Gwagwalada.

The prevalence of presbyopia in this rural study was 59.7%. This is slightly higher than the 53.4%5 reported in more urban Gwagwalada. The higher prevalence of presbyopia in a rural area than in an urban area is consistent with the findings of Nirmalan and co-workers in India13. This may be because the population in an urban area tends to be younger than that of a rural area. A hospital chart review based study by Morny reported a higher prevalence of presbyopia of 65% in Ghanaian women12. The higher prevalence in a female study population is similar to what other studies have documented3,4,13. Kamali et al reported a presbyopia prevalence of 48% in a study of ocular morbidity in Uganda11. However, the study in Uganda was a study of non-visual impairing ocular morbidity, from which patients presenting with VA less than 6/18 were excluded. This may thus account for the lower proportion of subjects with presbyopia. Burke et al3 reported a prevalence of presbyopia of 61.7% in Tanzania, comparable with the findings of this study.

In this study, a larger proportion of subjects aged 35 - 44years and those aged 65 - 74 years were presbyopic. However, among individuals aged 45-64 and those older than 75 more individuals were non-presbyopic. This may have been due to the presence of significant nuclear sclerosis which would have enabled some individuals to read N8 unaided.

Gender, level of education or occupation was not found to be significantly associated with presbyopia in this study. Female gender has been documented in some studies as being a risk factor for presbyopia3, 5, 13, 14. Burke et al reported a higher educational level and urban residence to be associated with presbyopia3. Conversely, Lu et al did not report any association of gender or educational level with presbyopia risk16. These differences reflect the fact that these risk factors may not have strong causal relationships with the development of presbyopia, and as such more studies may be required to provide the evidence to establish their importance.

Nearly half of the subjects with presbyopia (46.5%) reported having glasses that improved their near vision. This is far higher than the 21% recorded by Muhammad et al in Gwagwalada5. The relatively high presbyopic correction coverage in this study could be a function of different factors. One is the presence of an eye clinic in the community for a number of years which has brought glasses to the doorstep of many within the community. Another possible explanation is the frequent rate of ophthalmic outreaches/free eye screening within the state as a whole; part of the activities of the Kwara eye care programme. This might have made subsidized /free glasses available to a larger proportion of the population.

Skilled, retired and more educated people were more likely to have glasses compared with manual workers in this study. This is in consonance with other studies5,18. However, age and gender were not found to be associated with met need.

Other studies have found varied presbyopic correction coverage rates. The lowest rates were in African and Asian countries, and higher rates in more developed nations (Nigeria 21%5; India 30%13; Timor-Leste 26.2%18; China 51.5%16; Finland 68.2%14. These differences probably reflect better access to eye care, and better economic conditions that enables more people to pay for glasses.

The commonest barrier to obtaining near vision spectacles was cost (39.3%). The cost of glasses in the eye clinic of University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital in the community is between $5 and $8. Other barriers included being unaware of presbyopia as there was no perceived difficulty with near work (23.4%) and glasses not perceived as a priority. This is similar to the findings by Laviers et al and Muhammad et al5,15. Lu et al however reported that the major barriers to obtaining glasses were poor quality of available reading glasses, perception that vision was normal and lack of awareness that vision could be corrected, while lack of money was not reported as a major barrier to owning glasses16.

These differences in trends of barriers bring to the fore the economic differences in the various parts of the world where these studies were carried. Cost considerations are more severely felt in underdeveloped nations. The result is that a condition like presbyopia will easily become low priority for people with scant resources to meet other more pressing needs. It is recommended that increased funding be sought to further subsidise the cost of glasses provided at the eye clinic in the community.

This study had a few limitations. First, testing was done in ambient illumination under a shade. This could have introduced a pinhole effect which could give between 0.5-1.2 dioptres increase in depth of focus. Thus, the amount of presbyopia might have been underestimated to a certain extent. This study used the WHO standard testing distance of 40cm and the cutoff point of N8 which did not take into account the habitual working distance of subjects. In addition, some individuals already have some difficulty with near vision while reading N8. Despite these limitations, it is believed that the study protocol allowed for the realization of the study’s objectives.

Conclusions

Presbyopia is a major burden and cause of ocular morbidity in this rural community. Cost is the commonest barrier to obtaining near vision spectacles; increasing the availability of affordable spectacles for patients with presbyopia will help to overcome this challenge.

Acknowledgment

Many thanks to Dr Kabir Durowade and Dr Mubashir Uthman of the Department of Epidemiology, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital for their help with the design of the study protocol and revision of the final manuscript. Mr Afolabi, Mrs Adegoke, Mr Jimoh and Miss Faridat Ahmed were most helpful with pre-survey activities, enumeration procedures and data collection.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Grant support: None

References

- 1.Strenk SA, Semmlow JL, Strenk LM, Munoz P, Gronlund-Jacob J, DeMarco JK. Age-related changes in human ciliary muscle and lens: a magnetic resonance imaging study. . Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1162–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weale RA. Human ocular aging and ambient temperature. . Br J Ophthalmol. 1981;65:869–870. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.12.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke AG, Patel I, Munoz B, Kayongoya A, McHiwa W, Schwarzwalder AW, West SK. Population-based study of presbyopia in rural Tanzania. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weale RA. Epidemiology of refractive errors and presbyopia. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:515–543. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muhammad R, Jamda M. Presbyopic correction coverage and barriers to the use of near vision spectacles in rural Abuja, Nigeria. Sub-Saharan African Journal of Medicine . 2016;3:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nwosu SN. Ocular problems of young adults in rural Nigeria. Int Ophthalmol. 1998;22:259–263. doi: 10.1023/a:1006338013075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel I, Munoz B, Burke AG, Kayongoya A, McHiwa W, Schwarzwalder AW, West SK. Impact of presbyopia on quality of life in a rural African setting. Ophthalmology. . 2006;113:728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Org. . 2008;86:63–70. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Ho SM. Global vision impairment due to uncorrected presbyopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1731–1739. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.12.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashaye AO, Asuzu MC. Ocular findings seen among the staff of an institution in Lagos, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2005;24:96–99. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v24i2.28175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamali A, Whitworth JA, Ruberantwari A, Mulwanyi F, Acakara M, Dolin P, Johnson G. Causes and prevalence of non-vision impairing ocular conditions among a rural adult population in southwest Uganda. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1999;6:41–48. doi: 10.1076/opep.6.1.41.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morny FK. Correlation between presbyopia, age and number of births of mothers in the Kumasi area of Ghana. . Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1995;15:463–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nirmalan PK, Krishnaiah S, Shamanna BR, Rao GN, Thomas R. A population-based assessment of presbyopia in the state of Andhra Pradesh, South India: the Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2324–2328. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laitinen A, Koskinen S, Härkänen T, Reunanen A, Laatikainen L, Aromaa A. A Nationwide Population-Based Survey on Visual Acuity, Near Vision, and Self-Reported Visual Function in the Adult Population in Finland. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:2227–2237. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laviers HR, Omar F, Jecha H, Kassim G, Gilbert C. Presbyopic spectacle coverage, willingness to pay for near correction, and the impact of correcting uncorrected presbyopia in adults in Zanzibar, East Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1234–1251. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Q, He W, Murthy GV, He X, Congdon N, Zhang L, Li L, Yang J. Presbyopia and near-vision impairment in rural northern China. . Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. . 2011;52:2300–2305. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federa l. Lagos, Nigeria: Federal Government Printer; 2007. Legal Notice on the Publication of the Details of the Breakdown of the National and State Provisional Totals 2006 Census. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramke J, du Toit R, Palagyi A, Brian G, Naduvilath T. Correction of refractive error and presbyopia in Timor-Leste. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:860–866. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.110502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]