Abstract

Background

Studies have highlighted the direct impact of caries on the nutritional status of children; few studies in Nigeria have examined the association between the two parameters.

Aim

To determine the association between caries and the nutritional status of in-school children. Design of the study: A cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Two private and two public schools in Lagos state.

Methodology

A total of 973 children were assessed for dental caries using the WHO diagnostic criteria. Nutritional status was assessed using the weight for age, height for age and weight for height parameters. Data entry and analysis were done using WHO Epi 3.5 nutritstat and SPSS version 20.0 software. The t test, ANOVA, chi squared test, correlation statistics and logistic regression analysis were used as tests of association. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

Caries prevalence was 21.7% while mean Decayed Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index score was 0.48 (±1.135). Overall 13.9% of the children studied were stunted, 13.6% were wasted and 10.9% were underweight. The caries prevalence was significantly higher in children with normal weight than in overweight or underweight children (p=0.009). Children who were wasted (p=0.111) and those who were underweight (p=0.659) had a higher mean DMFT score, but the relationship was not statistically significant. The DMFT score was negatively correlated with weight for age but positively correlated with height for age and weight for height. The relationships were also not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Our results showed that underweight children had a higher risk of developing dental caries. Although both under weight and wasted children had higher mean DMFT scores, there was no significant association between dental caries and nutritional status.

Keywords: Dental caries, Nutritional status, Nigerian children

Introduction

Nutrition and diet are important in the development, growth and maintenance of oral tissues, likewise oral conditions can affect food choices and ultimately nutritional status1. Prior to tooth eruption nutritional deficiencies can affect enamel maturation and composition as well as tooth morphology and size2. While malnutrition may exacerbate periodontal and oral infectious diseases, the most noteworthy effect of nutrition in the oral cavity is the local action of diet on the oral tissues, specifically in the development of dental caries.

Dental caries is the most common chronic dental disease in children3 and a major threat to oral and general health4 It is also a major oral health problem in Nigeria with an incidence of 9.9%5 and a prevalence ranging between 11.2% and 48%5. The mean Decayed Missing and Filled Teeth index (DMFT) ranges from 0.02 to 0.85 in the permanent dentition; a mean DMFT index score greater than 1.0 is often only recorded in the primary dentition4,5. While the mean DMFT score is considered low among Nigerian children, the impact of the lesion is high. The proportion of children with untreated lesions is between 49.5% and 98.6%4 and the Pulpal exposure Ulceration Fistula formation Abscess (PUFA) scores of children with caries, an indicator of severity of caries was 0.056.

Caries is associated with significant morbidity and negatively influences the quality of life in children4-8. Fifty seven percent of children with caries experienced negative impact on their quality of life9 with eating being the worst affected domain. The quality of life is worse when the child has to live with the sequelae of untreated lesions10. The associated discomfort or toothache that results from untreated dental caries affects growth, cognitive development of young children and impacts weight gain11-13 which could result in the failure of the child to thrive14. The impact of caries on the growth and development of children could also affect the nutritional status of the affected child14,15. Poor nutritional status can increase a child’s susceptibility to dental caries especially in the primary dentition16.

Malnutrition, especially under-nutrition is highly prevalent in Nigeria17and the rapidly changing diet and lifestyle is increasing the prevalence of obesity in children18. Protein-energy malnutrition is still a major cause of childhood mortality in the Nigeria with one third of all children under-five being stunted, wasted or underweight19,20. There are few studies that have highlighted the direct impact of caries on the nutritional status of children. There is also a dearth of information available on the relationship between dental caries and nutritional status in developing countries like Nigeria where interventions’ to address nutritional disorders particularly under-nutrition among children is common. A potential relationship between nutritional status and dental caries occurrence may have implications for such programmes. A study exploring the association between caries and nutrition in Nigerian children by Denloye et al21 reported an inconclusive relationship between body mass index (BMI) and caries.

Most studies on caries and nutrition had focused on the body mass index (BMI) – an indirect measure of the nutritional status18. While BMI is a good epidemiological tool, the association of BMI with diseases still needs to be further studied20. The indicators for underweight (low weight-for-age), stunting (low height-for-age) or wasting (low weight-for-height), used in various combinations, are important measures of nutritional status in children as they capture different underlying biological processes. These indicators are less affected by factors that can affect the validity of the BMI22. Thus this study sought to determine the association between caries and the nutritional status of school children using nutritional parameters that assess underweight, stunning and wasting as well as identify the effect of nutritional status on caries prevalence in children.

Methodology

Study design and study population:

This was a cross-sectional survey conducted among in-school children aged 5 – 10 years, schooling in Ikeja Local Government Area (LGA) of Lagos State Nigeria. Ikeja is the capital of the state and an economic hub for the state, a variety of socio-economic classes are found in the local government area.

Sample Size:

It was estimated that a minimum sample size of 400 children was required to achieve a level of precision with a standard error of 2% or less using a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a prevalence of dental caries of 14.8% for the calculation23.

Sampling technique:

Data were collected from two private and two public schools in Ikeja LGA. The sampling frame, which was a list of schools in the LGA obtained from the Local Education Department, was stratified into public and private schools. Two of the eight public schools, and two of the eighteen private schools were selected from the list by balloting.

Study instrument:

Data on the socio-demographic profile was obtained from each study participant. These included information on the age, gender, as well as maternal and paternal education and occupation. Anthropometric measures were collected and clinical examinations were conducted to determine the dental caries status.

Study procedure:

The selected schools were formally notified of the proposed visit and approval from both school authorities and the children’s parents was sought. Each selected school was allocated a date for the data collection therefore data was collected on four separate dates. Only children with parental consent who were present on the data collection date for each school included were recruited for the study. The consent document was sent to the parents one week ahead of the school visit through the children.

During each school visit, the anthropometric measurements were taken. Weight was assessed using a Seca electronic weighing scale, which was calibrated against known weights. Height was measured using a stadiometer, and each child stood straight on the stadiometer without shoes. Next, the oral examination was conducted in the classroom under natural light using the World Health Organization criteria for assessing caries.24 Caries was recorded as present when there was obvious cavitation.

Standardisation of examiners:

Calibration of examiners was conducted prior to data collection. Duplicate examinations were carried out on randomly selected children to assess intra-examiner and inter-examiner agreement. A sample of 20 children was used when training the examiners. Inter examiner reliability using kappa was 0.73.

Statistical analysis:

The weight for age (WAZ), height for age (HAZ), and weight for height (WHZ) parameters were used to assess each child’s nutritional status. The parameters were calculated using WHO Epi 3.5 nutritstat software.

Using age and gender specific criteria, children were categorized as being at significant risk for either inadequate (< -2 SD) or excessive (> +2 SD) growth. The following were assessed: thinness or overweight using weight- for-age (WAZ), stunting using height-for-age (HAZ) and wasting using weight for height (WHZ) .25,26 Computed Z-scores of height for age (HAZ) were then used to assess nutritional status, using the WHO new reference values for school boys and girls.25,26 Nutritional status, an independent variable, was regrouped, stunting was defined as HAZ <-2.0, thinness as WAZ <-2.0, overweight as WAZ >1.0 and obesity as WAZ >2.0.

The dental caries status, a dependent variable, was categorized into a dichotomous variable: DMFT ≥ 1 and DMFT = 0 (caries free). Frequency tables were generated for all variables and mean scores computed for numerical variables. Chi-squared statistical test was used to determine association between nutritional status and caries occurrence, t-test and ANOVA the relationship between mean DMFT scores and nutritional status while Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to determine relationship between the DMFT scores and nutritional status. Analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20.0 and WHO Epi 3.5 nutritstat software. The probability level of p<0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical considerations:

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital.

Results

Socio-demographic features:

Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic, nutritional and dental characteristics of the study participants by type of school attended. Overall, 313 (32.1%) of the study participants attended a private school, 485 (49.8%) were female and 155 (15.9%) children reported a previous visit to the dentist. The mean age of the children examined was 7.79±1.486. The children’s weight ranged between 9kg and 68kg and the mean weight was 25.07±7.49 kg. Height ranged between 37cm and 180 cm and the mean was 124.5±11.42 cm.

Nutritional status:

Table 1 also highlights the nutritional status of the study participants. Most of the children had normal z scores for the parameters examined in this study. In all, 135 (13.9%) children were stunted, 132 (13.6%) were underweight and 106 (10.9%) were wasted.

More children who attended public schools were underweight than those in private schools. The difference was statistically significant (p=0.000). More children attending the public schools visited were stunted (89.6%), wasted (93.4%) and underweight (89.6%) when compared to children attending the private schools. The differences were statistically significant (p=0.000). More children attending the private schools studied were overweight (79.4%) when compared to children in the public schools. The differences were also statistically significant (p=0.000).

Table 2 explores the association between age, gender and the children’s nutritional status. Age was significantly related to the height for age parameter (p=0.000) as the highest prevalence of thinness was observed in 5 year old children (10.9%). Gender was also significantly related to the weight for height parameter (p=0.006), more females (11.1%) were overweight than males (10.7%) and more males (4.7%) were underweight than females (1.2%).

Caries status:

Caries prevalence for the study population was 21.7%. The DMFT ranged from 0 to 9 and the mean DMFT was 0.48 (±1.135). One hundred and forty eight (70.1%) of the 211 children with caries had untreated lesions, 8 (3.8%) children had restorations and 76 (36.0%) children had extracted carious teeth.

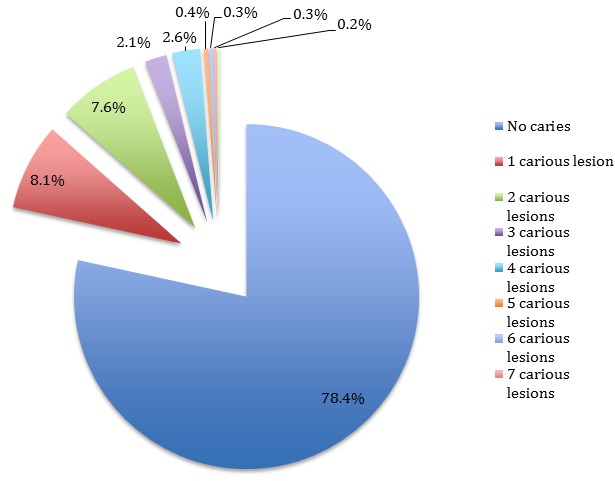

Figure 1 shows the proportion of children by number of lesions. Overall 762 (70.8%) children had no carious lesion. Furthermore, of those with dental caries 79 (8.1%) children with caries had one lesion while 74 (7.6%) had two lesions. The proportion of children with caries did not significantly differ by gender (p=0.266). Children aged 8 and 9 years were 29.3% and 29.9% caries free respectively. This results were statistically significant (p<0.05). More children in public schools (23.6%) had caries when compared with children in private schools (17.6%) and the result was statistically significant (p =0.035).

Association between caries status and nutritional status:

Tables 3 and 4 highlight the caries status of the children studied by nutritional status. The mean DMFT score was significantly higher in older than younger children. Underweight children have higher risk (OR =1.87; p=0.009) of developing dental caries. The mean DMFT score for children who were underweight was higher than that for children with normal weight but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.659). Similarly children who were wasted had a higher mean DMFT score, which was also not statistically significant (p=0.111). Children with stunting had a lower mean DMFT score than children with normal growth (p=0.203).

Table 5 highlights the outcome of the correlation analysis between DMFT and the nutritional status of the children studied. There was a negative correlation between child’s weight and DMFT as well as weight for height and DMFT. The relationships were not statistically significant. Conversely there was a positive correlation between height for age and DMFT as well as weight for age and DMFT.

Discussion

Our results revealed that under-nutrition was still a public health problem among the children surveyed and that significant differences exist in the nutritional status of children attending public and private schools. Children in public schools had a higher prevalence of under-nutrition while those in private schools had a higher prevalence of over nutrition. This was probably due to fact that more children in public schools were from the lower socio-economic strata in society. Our findings corroborated the results of an earlier study conducted in Lagos State although they reported a higher prevalence of both over and under nutrition27. The differences may be connected to the smaller sample size utilized in the earlier study as well as the fact that they included a wider age range than ours.

The prevalence of dental caries was 21.8%, which is similar to reports in other parts of the country28-30 although it was slightly higher than reported in the most recent statewide survey23. The difference can be explained by the fact that our study focused on children between the ages of 5 and 10 years unlike the statewide study, which focused on children aged 5 to 16 years. Our key finding was that underweight children had a higher risk of developing dental caries. Researchers have suggested that underweight and overweight children may be more susceptible to caries than normal children31,32. However, the other two nutritional parameters were not significantly related to caries occurrence among Nigerian children.

Our results also showed that children with wasting (WHZ < -2) had higher prevalence of caries and a higher mean dmft score. Underweight children also had higher prevalence of caries with an increased odds (1.87) of developing caries. Although mean DMFT scores for underweight children was also higher the association was not significant statistically. We observed a negative correlation between the child’s weight and the dmft score. While a similar result has been reported in some studies32,33 others have found no such association34,35. A study in Germany reported a positive correlation between weight and caries experience36.

Furthermore, the DMFT score was negatively correlated with weight for height. This indicates an inverse relationship between the DMFT and the child’s weight: the higher the DMFT the lower the weight and higher the likelihood of being underweight though this finding was statistically insignificant. In contrast with weight for age and height for age parameters were positively correlated with DMFT; none of these correlations were however statistically significant. Results from other countries have been conflicting, while some researchers report an associatio37,38 others have found none39,40. Caries is a multifactorial disease with several identified risk factors however the relationship between caries and nutritional status is not well understood and requires further research. In addition the relatively low prevalence of dental caries and malnutrition may obscure any real associations.

The main limitation of this study was its cross-sectional study design, limiting the ability to identify causal relationships. A longitudinal study would be a better study design for assessing the relationship between nutritional status and caries. However, since this was an exploratory study and the time to develop under or over nutrition and dental caries are similar we believe the results would be acceptable. Despite the fact that our results do not support an association between nutritional status and caries we suggest the conduct of longitudinal studies in future to assess the relationship between the two parameters.

Conclusions

Our results showed that underweight children had a higher risk of developing dental caries. Although both under weight and wasted children had higher mean DMFT scores, there was no significant association between dental caries and nutritional status.

Table 1: Nutritional parameters of the children in public and private schools.

| Variable | School Type | Chi Square(p – value) | ||

| Public (%) | Private (%) | Total (%) | ||

| Gender | 6.001(0.016)* | |||

| Male | 349 (71.5) | 139 (28.5) | 488 (50.2) | |

| Female | 311 (63.9) | 174 (35.6) | 485 (49.8) | |

| Previous Dental visit | 268.67(0.000)* | |||

| Yes | 18 (11.6) | 137 (88.4) | 155 (15.9) | |

| No | 643 (78.6) | 175 (21.4) | 818 (84.1) | |

| Weight for Age | 72.83(0.000)* | |||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 532 (65.9) | 275 (34.1) | 807 (82.9) | |

| Z score < -2 | 122 (92.4) | 10 (7.6) | 132 (13.6) | |

| Z score > +2 | 7 (20.6) | 27 (79.4) | 34 (3.5) | |

| Height for Age | 38.93(0.000)* | |||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 519 (69.3) | 276 (34.7) | 795 (81.7) | |

| Z score < -2 | 121 (89.6) | 14 (10.4) | 135 (13.9) | |

| Z score > +1 | 21 (48.8) | 22 (51.2) | 43 (4.4) | |

| Weight for Height | 66.59(0.000)* | |||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 557 (66.5) | 281 (33.5) | 838 (86.1) | |

| Z score < -2 | 99 (93.4) | 7 (6.6) | 106 (10.9) | |

| Z score > +2 | 5 (17.2) | 24 (82.8) | 29 (3.0) | |

| Total | 661 660(67.9) | 313 (32.1) | 973 (100.0) | |

| NB: Every table in a biomedical manuscript should have only 3 horizontal lines – two at the top to enclose the variables and the third at the bottom to end the table. There should also be no vertical lines. | ||||

Table 2: Nutritional parameters of Nigerian children by age and gender.

| Variable | Height for Age | Total | Chi Square(p – value) | ||

| >+2 | +2 to -2 | <-2 | |||

| Age | 40.372(0.000)* | ||||

| 5 | 5 (9.1) | 44 (80.0) | 6 (10.9) | 55 (5.7) | |

| 6 | 7 (4.3) | 140 (86.4) | 15 (9.3) | 162 (16.6) | |

| 6 | 27 (16.4) | 130 (78.8) | 8 (4.8) | 165 (17.0) | |

| 8 | 24 (12.1) | 168 (84.8) | 6 (3.0) | 198 (20.3) | |

| 9 | 35 (19.8) | 137 (77.4) | 5 (2.8) | 177 (18.2) | |

| 10 | 37 (17.1) | 176 (81.5) | 3 (1.4) | 216 (22.2) | |

| Gender | 0.082 (0.960) | ||||

| Male | 69 (14.1) | 397 (81.4) | 22 (4.5) | 488 (50.2) | |

| Female | 66 (13.6) | 398 982.1) | 21 (4.3) | 485 (49.8) | |

| Total | 135 (13.9) | 795 (81.7) | 43 (4.4) | 973 (100.0) | |

| Weight for Age | |||||

| >+2 | +2 to -2 | <-2 | Total | ||

| Age | 17.221 (0.070) | ||||

| 5 | 7 (12.7) | 45 (85.5) | 1 (1.8) | 55 (5.7) | |

| 6 | 14 (8.6) | 142 (87.7) | 6 (3.7) | 162 (16.6) | |

| 6 | 17 (10.3) | 143 (86.7) | 5 (3.0) | 165 (17.0) | |

| 8 | 23 (11.6) | 164 (82.8) | 11 (5.6) | 198 (20.3) | |

| 9 | 28 (15.8) | 143 (80.8) | 6 (3.4) | 177 (18.2) | |

| 10 | 43 (19.9) | 168 (77.8) | 5 (2.3) | 216 (22.2) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 62 (12.7) | 404 (82.8) | 22 (4.5) | 488 (50.2) | 3.41(0.181) |

| Female | 70 (14.4) | 403 (83.1) | 12 (2.5) | 485 (49.8) | |

| Total | 132 (13.6) | 807 (82.9) | 34(3.5) | 973 (100.0) | |

| Weight for Height | |||||

| >+2 | +2 to -2 | <-2 | Total | ||

| Age | 13.214(0.212) | ||||

| 5 | 8 (14.5) | 47 (85.5) | 0 (0.0) | 55 (5.7) | |

| 6 | 24 (14.8) | 131 (80.9) | 7 (4.3) | 162 (16.6) | |

| 6 | 20 (12.1) | 143 (86.7) | 2 (1.2) | 165 (17.0) | |

| 8 | 17 (8.6) | 171 (86.4) | 10 (5.1) | 198 (20.3) | |

| 9 | 16 (9.0) | 56 (88.1) | 5 (2.8) | 177 (18.2) | |

| 10 | 21(9.7) | 190 (88.0) | 5 (2.3) | 216 (22.2) | |

| Gender | 10.166 (0.006)* | ||||

| Male | 52 (10.7) | 413 (84.6) | 23 (4.7) | 488 (50.2) | |

| Female | 54 (11.1) | 425 (87.6) | 6 (1.2) | 485 (49.8) | |

| Total | 106 (10.9) | 838 (86.1) | 29(3.0) | 973 (100.0) | |

Table 3: Demographic and Nutritional parameters of the children.

| Variable | Caries Status | Odds Ratio(p – value) | ||

| Absent (%) | Present (%) | Total (%) | ||

| Age | ||||

| 5 | 6 (10.9) | 49 (89.1) | 55 (5.7) | 1.706 (0.756) |

| 6 | 28 (17.3) | 134 (82.7) | 162 (16.6) | 2.042 (0.444) |

| 7 | 33 (20.0) | 132 (80.0) | 165 (17.0) | 3.383 (0.015)* |

| 8 | 58 (29.3) | 140 (70.7) | 198 (20.3) | 3.491 (0.013)* |

| 9 | 53 (29.9) | 124 (70.1) | 177 (18.2) | 1.473 (1.000) |

| 10 | 33 (15.3) | 183 (84.7) | 216 (22.2) | 1.706 (0.756) |

| Gender | 1.189(0.266) | |||

| Male | 389 (79.7) | 99 (20.3) | 488 (50.2) | |

| Female | 373 (76.9) | 112 (23.1) | 485 (49.8) | |

| Type of School | 1.443(0.035)* | |||

| Public School | 505 (76.4) | 56 (23.6) | 661 (67.9) | |

| Private School | 257 (82.4) | 55 (17.6) | 312 (32.1) | |

| Weight for Age | ||||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 627 (77.7) | 275 (22.3) | 807 (82.9) | |

| Z score < -2 | 107 (81.1) | 25 (18.9) | 132 (13.6) | 1.877 (0.009)* |

| Z score > +2 | 28 (82.4) | 6 (17.6) | 34 (3.5) | 2.047 (0.176) |

| Height for Age | ||||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 614 (77.2) | 181 (22.8) | 795 (81.7) | |

| Z score < -2 | 111 (82.2) | 24 (17.8) | 135 (13.9) | 1.363 (0.338) |

| Z score > +2 | 37 (86.0) | 6 (14.0) | 43 (4.4) | 1.818 (0.286) |

| Weight for Height | ||||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 657 (78.4) | 181 (21.6) | 838 (86.1) | |

| Z score < -2 | 81 (76.4) | 25 (23.6) | 106 (10.9) | 0.893 (0.873) |

| Z score > +2 | 24 (82.8) | 5 (17.2) | 29 (3.0) | 1.377 (0.755) |

| Total | 762 (78.3) | 211(21.7) | 973 (100.0) | |

Table 4: Caries severity by nutritional status in the children.

| Variable | Mean DMFT (SD) | N | F Statistic(p-value) |

| Age | 2.986(0.011)* | ||

| 5 | 0.20 (0.672) | 55 | |

| 6 | 0.47 (1.339) | 162 | |

| 7 | 0.51 (1.187) | 165 | |

| 8 | 0.60 (1.197) | 198 | |

| 9 | 0.57 (1.085) | 177 | |

| 10 | 0.28 (0.828 | 216 | |

| Gender | 0.364(0.546) | ||

| Male | 0.46 (1.181) | 488 | |

| Female | 0.50 (1.090) | 485 | |

| Type of School | 0.522(0.470) | ||

| Public School | 0.44 (1.079) | 661 | |

| Private School | 0.50 (1.246) | 312 | |

| Recoded OHI Score | 2.264(0.133) | ||

| Good | 0.43 (1.091) | 608 | |

| Fair | 0.55 (1.203) | 365 | |

| Weight for Age | 0.418(0.659) | ||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 0.49 (1.099) | 807 | |

| Z score < -2 | 0.52 (1.390) | 132 | |

| Z score > +2 | 0.32 (0.843) | 34 | |

| Height for Age | 1.597(0.203) | ||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 0.51 (1.175) | 795 | |

| Z score < -2 | 0.33 (0.809) | 135 | |

| Z score > +2 | 0.40 (1.237) | 43 | |

| Weight for Height | 2.201(0.111) | ||

| -2 ≤ Z score≤+2 | 0.46 (1.072) | 838 | |

| Z score < -2 | 0.69 (1.576) | 106 | |

| Z score > +2 | 0.34 (0.897) | 29 | |

| TOTAL | 0.48 (1.136) | 973 | |

Table 5: Correlation between caries occurrence, socio-demographic factors and nutritional status.

| DMFT SCORE | DICHOTOMOUS | |||

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p-value | Correlation Coefficient | p-value |

| Age | 0.019 | 0.561 | 0.028 | 0.386 |

| Oral Hygiene Score | 0.071 | 0.041* | 0.077 | 0.026* |

| Weight | -0.24 | 0.449 | -0.22 | 0.495 |

| Weight for Age | 0.008 | 0.809 | 0.009 | 0.782 |

| Height for Age | 0.022 | 0.490 | 0.021 | 0.515 |

| Weight for Height | -0.077 | 0.139 | -0.067 | 0.201 |

| * = Significant | ||||

| 78% of the children had no carious lesion, 8% had 1 carious lesion, 7.6% had 2 carious lesions, 2.1% had 3 carious lesions, 2.6% had 4 carious lesions, 0.4% had 5 carious lesions, 0.3% had 6 carious lesions, 0.3% had 7 carious lesions and 0.2% had 9 carious lesions. | ||||

Fig. 1: Severity of caries occurence.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Grant support: None

References

- 1.Ritchie CS, Joshipura K, Hung HC, Douglass CW. Nutrition as a mediator in the relation between oral and systemic disease: Associations between specific measures of adult oral health and nutrition outcomes. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13(3):291–300. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rugg-Gunn AJ. Nutrition and Dental Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. Nutrition, dental development and dental hypoplasia. pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EM. Oral health: the silent epidemic. Pub Health Rep. 2010;125(2):158–159. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folayan MO, Chukwumah NM, Onyejaka N, Adeniyi AA, Olatosi OO. Appraisal of the national response to the caries epidemic in children in Nigeria. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folayan MO, Adeniyi AA, Chukwumah NM, Onyejaka N, Esan AO, Sofola OO, Orenuga OO. Programme guidelines for promoting good oral health for children in Nigeria: a position paper. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oziegbe EO, Esan TA. Prevalence and clinical consequences of untreated dental caries using PUFA index in suburban Nigerian school children. Eur Arch PaediatrDent. 2013;14(4):227–231. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folayan MO, Sofola OO, Oginni AB. Caries incidence in a cohort of primary school students in Lagos State, Nigeria followed up over a 3 years period. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2012;13(6):312–318. doi: 10.1007/BF03320833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chukwumah N, Azodo C, Orikpete E. Analysis of tooth mortality among Nigerian children in a tertiary hospital setting. Ann Med Health Sci Res . 2014;4(3):345–349. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.133457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chukwumah NM, Folayan MO, Oziegbe EO, Umweni AA. Impact of dental caries and its treatment on the quality of life of 12- to 15-year-old adolescents in Benin, Nigeria. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2016;26(1):66–76. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratnayake N, Ekanayake L. Prevalence and impact of oral pain in 8-year-old children in Sri Lanka. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15(2):105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2005.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acs G, Lodolini G, Kaminski S, Cisneros GJ. Effect of nursing caries on body weight in a pediatric population. Pediatr Dent. 1992;14(5):302–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acs G, Shulmann R, Ng MW, Chussid S. The effect of dental rehabilitation on the body weight of children with early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas CW, Primosch RE. Changes in incremental weight and well-being of children with rampant caries following complete dental rehabilitation. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24(2):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elice CE, Fields HW. Failure to thrive: review of the literature, case report and implications for dental treatment. Pediatr Dent. 1990;12(3):185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660–667. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvarez JO. Nutrition tooth development and dental caries. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;61(2):410s–416s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.2.410S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller O, Krawinkel M. Malnutrition and health in developing countries. CMAJ. 2005;173(3):279–286. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prentice AM. The emerging epidemic of obesity in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(1):93–99. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO World. WHO Techniques Report Series. Vol. 854. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. Expert Committee on Physical Status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry physical status. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung S. Body mass index and body composition scaling to height in children and adolescent. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;20(3):125–129. doi: 10.6065/apem.2015.20.3.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denloye O, Popoola B, Ifesanya J. Association between dental caries and body mass index in 12–15 year old private school children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ped Dent J. 2016;26(1):28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corsi DJ, Subramanyam MA, Subramanian SV. Commentary: Measuring nutritional status of children. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):1030–1036. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adeniyi AA, Agbaje MO, Onigbinde OO, Ashiwaju O, Ogunbanjo O, Orebanjo O, Adegbonmire O, Adegbite K. Prevalence and pattern of dental caries among a sample of Nigerian public primary school children. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2012;10:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO . Basic methods. 4th ed. Geneva: Word Health Organization; 1997. Oral health surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO . Methods and development. Geneva, Switzerland.: Word Health Organization; 2006. Child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for- age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index- for-age. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health. Expert Committee: An estimate for the prevalence of child malnutrition in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1985;38:331–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekekezie OO, Odeyemi KA, Ibeabuchi NM. Nutritional status of urban and rural primary school pupils in Lagos State, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2012;31(4):232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sho-Silva VE. Pattern of caries in children age 3 – 10 years: a study of the private and public school children in Surulere Local Government Area. 2004. An unpublished dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Surgery of the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria in partial fulfillment of the award of the Fellowship of the College. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giwa AA. Oral health status of 12 year old school children in Private and Public Schools in Lagos State. 2005. An unpublished dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Surgery of the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria in partial fulfillment of the award of the Fellowship of the College. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sofola OO, Folayan MO, Oginni AB. Changes in the prevalence of dental caries in primary school children in Lagos State, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:127–133. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.127419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliveira LB, Sheiham A, Bönecker M. Exploring the association of dental caries with social factors and nutritional status in Brazilian preschool children. Euro J Oral Sciences. 2008;116(1):37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kantovitz KR, Pascon FM, Rontani RM, Gaviao MB. Obesity and dental caries: a systematic review. Oral Health Prev Dent. . 2006;4(2):137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheiham A. Dental caries affects body weight, growth, and quality of life in pre-school children. Br Dent J. 2006;201(10):625–626. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4814259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreira PV, Rosenblatt A, Severo AM. Prevalence of dental caries in obese and normal-weight Brazilian adolescents attending state and private schools. Community Dent Health. 2006;23:251–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macek MD, Mitola DJ. Exploring the association between overweight and dental caries among US children. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28(4):375–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willerhausen B, Blettner M, Kasaj A, Hohenfellner K. Association between body mass index and dental health in 1,290 children of elementary schools in a German city. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11(3):195–200. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narksawat K, Tonmukayakul U, Boonthum A. Association between nutritional status and dental caries in permanent dentition among primary schoolchildren aged 12-14 years, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(2):338–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willershausen B, Moschos D, Azrak B, Blettner M. Correlation between oral health and body mass index (BMI) in 2071 primary school pupils. Euro J Med Res. 2007;12(7):195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamelli SR, Rodrigues CS, de Lira PI. Nutritional status and prevalence of dental caries among 12-year-old children at public schools: a case-control study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8(1):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whelton H, Crowley E, Cronin M, Kelleher V, Perry I, O’Mullane D. Ireland: University College Cork; 2004. The Relationship between Body Mass Index (BMI) and Dental Caries. [Google Scholar]