Abstract

We examined whether neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) interact with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers (amyloid-β42 [Aβ42], tau, phosphorylated tau181 [ptau181], tau/Aβ42, and ptau181/Aβ42) of Alzheimer's disease pathology to predict driving decline among cognitively-normal older adults (N=116) aged ≥65. Cox proportional hazards models examined time to receiving a rating of marginal or fail on the driving test. Age, education, and gender were adjusted in the models. Participants with more abnormal CSF (Aβ42, tau/Aβ42, ptau181/Aβ42) and NPS were faster to receive a marginal/fail on the road test compared to those without NPS. NPS interact with abnormal CSF biomarkers to impact driving performance among cognitively-normal older adults.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, cerebrospinal fluid, depression, neuropsychology, noncognitive outcomes, preclinical

Introduction

Over the next 40 years in the United States, the number of older adults age ≥65 will double, when 25% of all drivers will be an older adult and the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease (AD) will increase to almost 14 million [1]. Changes in cognitive and neurobehavioral processes begin in the long preclinical stage of AD [2]. Early identification of these changes prior to symptomatic AD can help to understand the resulting impact on complex activities and functional outcomes like driving. Recent work has shown that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and imaging biomarkers predict driving problems and longitudinal driving decline among cognitively normal older adults [3, 4]. Institutions like the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer's Association recommend research into neurobehavioral outcomes like mood disorders to link the pathological changes to emerging AD symptoms in order to determine the impact on functional decline prior to full symptom onset [5].

Mood states like depression, anger, and anxiety also negatively impact driving behaviors [6]. In older adults, mood states and neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) predict progression to symptomatic AD [7, 8]. Additionally, changes in mood have been associated with CSF and imaging biomarkers [9]. It is possible that the combined impact of abnormality in CSF biomarkers, mood states, and NPS could be larger than the additive effects of each. We therefore examined whether mood states and NPS interacted with AD biomarkers to predict future driving problems among cognitively normal older adults.

Materials and Methods

Design

Data were used from individuals, in a longitudinal study (AG043434) at the Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who had processed CSF data available for analyses. Participants were required to be cognitively normal (Clinical Dementia Rating = 0 [CDR]) [10], English-speaking, aged 65 years or older, have a valid driver's license, and driving at least once a week. At baseline evaluation, participants underwent biomarker testing, as well as clinical and psychometric assessments, followed by a standardized performance-based road test [3, 4]. At annual follow-ups, participants completed clinical and psychometric assessments and the road test. Washington University Human Research Protection Office approved all study protocols, consent documents, and questionnaires (no. 201208161).

Mood states and NPS

Mood was evaluated by baseline measures of the Profile of Mood States-short form (POMS-SF) [11] and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [12], while NPS was evaluated by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) [13]. The POMS-SF is a 30-item questionnaire that assesses six mood states (anxiety, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, confusion) and provides a total mood disturbance score (TMD) ranging from −20 to 100, while the GDS is a brief 15-item depression screen with scores ranging from 0–15; both are completed by the participant. The NPI-Q is a 12-item survey of behavioral domains and presence of symptoms and associated severity with scores ranging from 0 to 36. The domains include: delusion, hallucination, agitation, depression, anxiety, elation, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite. The NPI-Q is completed by a collateral source. At our ADRC, the collateral source are generally female (70%), are a spouse (46%) or adult child (38%), interacts with the participant daily, and has typically known the participant for approximately 30–60 years [14]. Higher scores on all three measures indicate increased problems.

CSF measurement

Following an overnight fast, trained neurologists obtained samples via standard lumbar puncture using a 22-gauge Sprotte spinal needle to draw 20–30mL of CSF at 8:00 AM. All samples were gently inverted and centrifuged at low speed to avoid potential gradient effects and frozen at −84°C after aliquoting into polypropylene tubes. Levels of amyloid-β42 (Aβ42), total tau, and phosphorylated tau181 (ptau181) were obtained and measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (INNOTEST; Fujiebio [formerly Innogenetics], Ghent, Belgium). Lower levels of Aβ42 indicate amyloid plaque accumulation while higher levels of tau and ptau181 indicate neuronal injury/degeneration; elevated ratios of tau/Aβ42 and ptau181/Aβ42 indicate more AD pathologic burden [15].

Road test

Participants completed the standardized Washington University Road Test, [16, 17] a 12-mile course starting from a closed parking lot and progressing into traffic with complex intersections and unprotected left hand turns. An examiner in the front seat provided direction and evaluated the driving performance of the participant. A pass (no problems/errors), marginal (some safety concerns and errors), or fail (high risk and errors) rating was assigned at the end of the road test via a standardized scoring system.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics examined demographic variables and normal distribution of predictors and outcome variables. Similar to our previous work [3, 4], we compared the lowest tertile to the other two tertiles for Aβ42; for remaining biomarker values, the highest tertile was compared to the lower two tertiles in our analyses. Compared to normative scores, baseline scores on all subscales of the POMS-SF, GDS, and NPI-Q indicated little to no disturbance as self-reported by participants or collateral source. As a result, scores on the POMS, GDS, and NPI-Q were dichotomized into 0 (no problems) if no items were endorsed and 1 (some problems) if participants/collateral source endorsed any item. Driving decline was examined as time from baseline to receiving a rating of Marginal or Fail on the road test. At baseline, all participants received a pass rating on the road test. Cox proportional hazards models (CPHM) were used to examine whether values of each CSF biomarker were associated with time from baseline to receiving a rating of Marginal or Fail on the driving test while adjusting for, and simultaneously testing the effects of, age, education, and gender. Separate models examined the POMS, GDS, and NPI-Q and the interaction with the CSF biomarkers. Secondary analyses examined the effect of apolipoprotein (APOE) allele ε4 status. In the Cox models, data from participants who did not return for follow-up, or who did not receive a rating of Marginal/Fail on the driving test by the end of the follow-up period, were censored at the date of the most recent driving assessment session.

Results

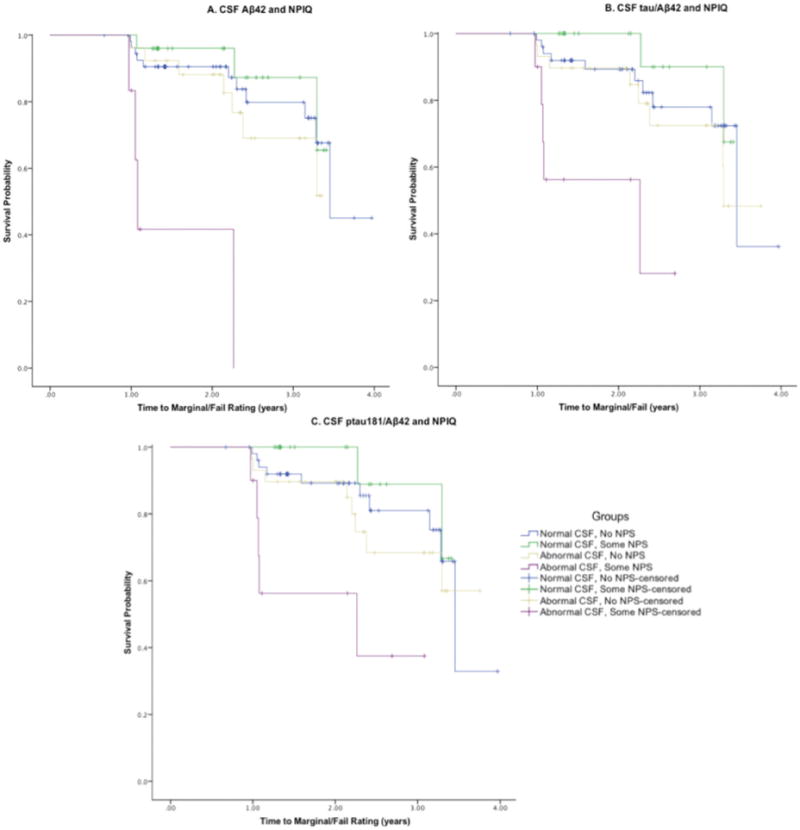

Data were available from 116 participants with ages ranging from 65.6 to 88.2 years (Table 1). Follow-up period ranged from 0.67 to 3.97 years with a mean of 2.1 years. The CPHM showed that interactions between NPI-Q and Aβ42, tau/Aβ42, and ptau181/Aβ42 biomarkers were significant in predicting time to a rating of Marginal/Fail on the road test. Hazard ratios were 10.6 for Aβ42 (95% CI: 1.64–68.38; p < 0.013), 8.23 for tau/Aβ42 (95% CI: 1.21–55.94; p < 0.031), and 7.3 for ptau181/Aβ42 (95% CI: 1.07–49.35 p < 0.042). Participants with NPS and more abnormal levels of Aβ42, tau/Aβ42, and ptau181/Aβ42 were much faster to receive a marginal/fail rating on the road test compared to participants with no NPS or non-abnormal biomarkers (Fig. 1). There were no associations between POMS and GDS with time to marginal/fail, nor were the interactions significant between the POMS or GDS with CSF biomarkers. There were no significant effects found for age, gender, and education in the models. On the NPI-Q, the most commonly endorsed items were irritability (20), appetite (11), depression (11), and agitation (8). There were 18 out of 31 participants with two or more NPS reported and an associated 5 out of 7 Marginal/Fail rating on the road test. In secondary analyses, APOE4+ was not statistically significant when added to the models nor did APOE4+ impact relationship between CSF biomarkers and NPS.

Table 1. Baseline demographics (N= 116)*.

| Age, y | 72.4 ±4.6 |

| Education, y | 16.3 ±2.5 |

| Women, N | 61 (52.6%) |

| Race, Caucasian, N | 105 (90.5%) |

| APOE4+, N | 33 (28.4%) |

| Biomarkers | |

| CSF Aβ42, pg/mL | 864.2 ± 325.7 |

| CSF tau, pg/mL | 347.5 ± 197.6 |

| CSF ptau181, pg/mL | 63.3 ± 30.0 |

| CSF tau/Aβ42 | 0.50 ± 0.49 |

| CSF ptau181/Aβ42 | 0.90 ± 0.08 |

| Participant endorsing some mood/NPS problems | |

| POMS TMD, N | 25 (21.5%) |

| Normal CSF biomarker | 10 (8.4%) |

| Abnormal CSF biomarker | 15 (12.9%) |

| GDS, N | 59 (50.8%) |

| Normal CSF biomarker | 25 (21.5%) |

| Abnormal CSF biomarker | 34 (29.3%) |

| NPI-Q, N | 31 (26.7%) |

| Normal CSF biomarker | 18 (15.5%) |

| Abnormal CSF biomarker | 13 (11.2%) |

APOE4+, Apolipoprotein allele ε4; Aβ42, amyloid-β42; ptau181, phosphorylated tau181; POMS-SF, Profile of Mood States – Short Form; TMD, Total Mood Disturbance; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire.

Mean±SD or percentage.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves describing group interactions between CSF biomarkers and the NPIQ in predicting time to a rating of Marginal/Fail on the road test. Aβ42, amyloid-β42; ptau181, phosphorylated tau181; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire.

Discussion

AD biomarkers are actively being used in research studies to delineate a time course of the preclinical stages and to understand the impact on functional activities. Driving problems arise earlier for participants with preclinical AD [3]. Symptomatic AD (CDR >0) is associated with much faster decline on the NPI-Q than cognitive normality (CDR 0) [7]. In our sample of cognitively normal older adults, presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms interacted with CSF biomarkers to predict a much faster time to receiving a marginal/fail rating on a road test. While preclinical AD alone predicted a faster time to receiving a marginal/fail rating [3], the presence of NPS increases these problems compared to those without preclinical AD or NPS.

While NPS interacted with the biomarkers, the POMS and GDS biomarker interactions were not significant in the models and the main effects of these variables were not associated with time to marginal/fail. One explanation may be that constructs like NPS and moods are different in how they are experienced by a person and expressed in the presence of others. Another explanation may be that the NPI-Q is filled out by the collateral source while the participant fills out the POMS and GDS. Participants may not be aware of problems they are having, thus leading to underreporting of neurobehavioral changes. The CDR recognizes this issue and requires inclusion of a collateral source in the interview to determine staging [10]. Neuropsychological testing of global and specific cognitive functioning may not be sensitive enough to detect differences in biomarker groups in preclinical AD [3, 9]. Changes in mood and NPS may precede cognitive decline and can be easily screened in cognitively normal older adults. Putative models of preclinical AD and its pathophysiology [5] should be updated to include changes in emotive domains like mood and NPS and functional activities like driving. These outcomes may serve as noncognitive and functional biomarkers that can provide critical information about early changes in preclinical AD. Given the current intensive work on non-invasive biomarkers of preclinical AD, assessment of mood and NPS will contribute to the eventual development of risk models to predict when driving problems and decline will occur in the aging population.

There are some limitations to our study. Participants were well educated, predominately Caucasian, and willing to undergo a lumbar puncture and may not be representative of the larger population. Despite these limitations, our findings support the use of NPS and biomarkers in predicting changes in driving decline. Further work is needed to examine longitudinal changes in mood states and NPS in cognitively normal older adults and the resulting impact on driving decline and driving cessation.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging [R01-AG043434, P50-AG05681, P01-AG03991, P01-AG026276]; Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan, and the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer's Research Initiative of the Washington University Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC). The authors thank the participants, investigators, and staff of the Knight ADRC Clinical Core (participant assessments), the investigators and staff of the Driving Performance in Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease study (R01-AG043434), and the investigators and staff of the Biomarker Core for the Adult Children Study (P01-AG026276) for cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging [R01-AG043434, P50-AG05681, P01-AG03991, P01-AG026276]; Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan, and the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer's Research Initiative of the Washington University Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center.

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/17-0067r2).

References

- 1.National Center for Statistics and Analysis. Older Population: Traffic Safety Facts 2012 Data. US Department of Transportation; 2015. Available from: https://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/812005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling RA, Karlawish J, Johnson KA. Preclinical Alzheimer disease—the challenges ahead. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:54–58. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roe CM, Babulal GM, Head D, Stout SH, Vernon EK, Ghoshal N, Garland B, Williams MM, Johnson A, Fierberg R, Fague MS, Xiong C, Mormino EC, Grant EA, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ott BR, Carr DB, Morris JC. Preclinical Alzheimer disease and longitudinal driving decline. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;3:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roe CM, Barco PP, Head DM, Ghoshal N, Selsor N, Babulal GM, Fierberg R, Vernon EK, Shulman N, Johnson A, Fague S, Xiong C, Grant EA, Campbell A, Ott BR, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Carr DB, Morris JC. Amyloid imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers predict driving performance in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31:69–72. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrity RD, Demick J. Relations among personality traits, mood states, and driving behaviors. J Adult Dev. 2001;8:109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masters MC, Morris JC, Roe CM. “Noncognitive” symptoms of early Alzheimer disease A longitudinal analysis. Neurology. 2015;84:617–622. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismail Z, Smith EE, Geda Y, Sultzer D, Brodaty H, Smith G, Agüera-Ortiz L, Sweet R, Miller D, Lyketsos CG. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: Provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babulal GM, Ghoshal N, Head D, Vernon EK, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Roe CM. Mood changes in cognitively normal older adults are linked to Alzheimer disease biomarker levels. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:1095–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL. Short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychol Assessment. 1995;7:80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montorio I, Izal M. The Geriatric Depression Scale: A review of its development and utility. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8:103–112. doi: 10.1017/s1041610296002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, Smith V, MacMillan A, Shelley T, Lopez OL, DeKosky ST. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cacchione PZ, Powlishta KK, Grant EA, Buckles VD, Morris JC. Accuracy of collateral source reports in very mild to mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:819–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid tau/β-amyloid42 ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:343–349. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.noc60123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr DB, Barco PP, Wallendorf MJ, Snellgrove CA, Ott BR. Predicting road test performance in drivers with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2112–2117. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duchek JM, Carr DB, Hunt L, Roe CM, Xiong C, Shah K, Morris JC. Longitudinal driving performance in early-stage dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1342–1347. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]