Abstract

Objective

To examine the association of vascular pathology with the rate of cognitive decline in older adults, independent of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Community sample.

Participants

62 individuals from the Einstein Aging Study autopsy series.

Measurements

The analysis includes The Blessed-information memory-concentration test was used to assess global cognitive status. AD pathology was quantified using Braak stage (<3 vs. ≥ 3). Vascular pathology was quantified using a previously reported Macrovascular Lesion Score (MVLs). The association of vascular pathology with antemortem rates of cognitive decline adjusted for level of AD pathology was assessed using linear mixed effects models.

Results

The mean age at enrollment was 81.8 and the mean age at death was 89.0 years. Compared to persons free of vascular lesions, those with more than 2 MVLs showed faster cognitive decline (difference in annual rate of change in BIMC=0.74 points/year; p=0.03). Braak stage was also associated with greater cognitive decline (difference=0.57 points/year, p=0.03). The difference in rate of cognitive decline between those with more than 2 MVLs and those free of vascular lesions persisted after adjustment for AD pathology (difference in rate of change in BIMC=0.68 points/year, p=0.04). The effect of vascular pathology on cognitive decline was not significantly different among individuals with low or high AD pathology.

Conclusion

Vascular brain pathology is associated with the rate of cognitive decline after adjusting for level of AD pathology.

Keywords/Search terms: Vascular pathology, Alzheimer disease pathology, Cognitive decline, cerebrovascular disease

Introduction

While the clinical syndromes of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) were previously considered to be the result of independent processes, it is now recognized that vascular disease and vascular risk factors may contribute to dementia regardless of subtype.1–3 Recent community-based neuropathological studies have revealed that AD and vascular pathologies frequently occur in the same individuals and that the most common etiology of dementia in the elderly is mixed vascular and AD pathology. 4, 5 The functional and pathogenic synergy between neurons, glia, and vascular cells suggested by prior studies, 6–8 provide a framework to evaluate how cerebrovascular disease might contribute to the neuronal dysfunction underlying cognitive impairment.

Data from imaging and clinical-neuropathological correlation studies have suggested that the presence of vascular pathology exacerbates the clinical presentation of AD and increases risk of clinically evident cognitive impairment. 9, 10 However, the extent to which vascular pathology contributes to cognitive decline independent of AD pathology has not been well established in community based autopsy series. Better understanding the relationship of vascular pathology to cognitive decline would enhance the ability to develop strategies for prevention or slowing of cognitive decline and progress to dementia.

The Einstein Aging Study autopsy series provides the opportunity to explore the association of vascular lesions with ante-mortem cognitive decline, and to test whether this association is independent of AD pathology. Previously, we have described development of a summary vascular score to quantify macroscopic vascular lesions (MVLs) and have reported that increasing vascular burden is associated with probability of ante-mortem diagnosis of clinical dementia.11 The aim of current study was to examine whether vascular lesion burden is independently associated with antemortem rate of cognitive decline after adjusting for level of AD pathology.

Methods

Study population

The analysis includes individuals enrolled in the Einstein Aging Study (EAS) autopsy study. Among the 86 EAS autopsy cases who completed an antemortem neuropsychological battery since 1993, the analysis excluded those with dementia at study baseline (N=14), and those with greater than 5 years between last study visit and time of death (N=10). The final analysis sample is comprised of 62 subjects. Methods of recruitment, subject examination, determination of cognitive status, and exclusion criteria from the overall cohort have been described previously.11, 12

Written informed consent for clinical evaluation as well as the autopsy program was obtained from all subjects and surrogate decision makers at enrollment, using protocols approved by the local institutional review board.

1.2. Cognitive assessment

Subjects completed clinical and neuropsychological evaluations at enrollment and every 12–18 months. Clinical evaluations were completed by board-certified neurologists with expertise in geriatric neurology. All participants completed a standardized neuropsychological battery validated for use in normal aging populations.13 BIMC was used to screen for global cognitive status. This test has a high test–retest reliability (0.86) and correlates well with AD pathology.14, 15

Dementia was diagnosed by case conference consensus, using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Fourth edition. 16, 17 The study neurologists, licensed neuropsychologist, and a study social worker reviewed all available clinical and neuropsychological data. Participants with dementia at enrollment were excluded for the purposes of this analysis.

1.3. Neuropathology

A single experienced neuropathologist, blinded to clinical status, provided neuropathological evaluations. Details of brain autopsy and pathological processing has been described in detail previously11. All cases were assigned a Braak neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) stage 18, based upon the distribution of NFT on thioflavin-S sections. For analysis Braak NFT stage was dichotomized as low (< 3) versus high (>=3).

Ischemic vascular lesions were identified by macroscopic examination of 0.5-cm thick coronal sections of cerebral hemispheres and transverse sections of brainstem and cerebellum. The three types of macrovascular lesions used for the purpose of this study included ischemic vascular lesions (large infarcts and lacunar infarcts) and leukoencephalopathy. Circumscribed areas of softening (encephalomalacia), whether cystic or partially cystic, with maximum diameter greater than one centimeter were classified as large infarct. Lacunar infarcts were defined as cystic lesions less than one centimeter in diameter. Lacunar infarcts, which correlate with the presence of small vessel arteriosclerotic vascular disease, were most often found in basal ganglia, thalamus, pontine base, and periventricular white matter. Leukoencephalopathy was assessed based on the presence of rarefaction of the white matter, dilation of perivascular spaces in the white matter and the presence of reactive astrocytes and less often macrophages. Acute and subacute infarcts, lacunes, microinfarcts or hemorrhages near the time of death were noted, but not included in the vascular scores or analyses. The decision to exclude was based upon the histological appearance of the lesions, and presence of acute neuronal necrosis and neutrophils.

2.5. Vascular score

To understand the clinical relevance of our findings as well as to study the effect of cumulative vascular burden irrespective of type of vascular lesion, Similar to our previous study 11 we used a summary pathological vascular lesion score based on the presence and number of three types of macroscopic vascular lesions (large infarct, lacunar infarct, and leukoencephalopathy) that are associated with neuroimaging correlates during life. Details of the score are presented in Supplemental Table S1. MVLs were studied as a categorical variable (no vascular lesions, one or two vascular lesions, and more than 2 MVLs) to look for a possible threshold effect of vascular burden on cognitive impairment.

2.6. Data analysis

Clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, and comparisons among levels of MVL used ANOVA and Chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

We used linear mixed-effect models to assess the association of vascular and AD pathology with the trajectory of cognitive function prior to death, where BIMC score was modeled as a function of time in years since enrollment, age at enrollment, sex, years of education, and presence of vascular and/or AD pathology. A random intercept and random slope were used to account for within-person variation. Robust empirical estimates of standard errors were used to take account the skewed distribution in BIMC.19 The association of MVL and Braak stage with cognitive decline were evaluated separately as well as jointly. Possible interactions between MVL score and Braak stage was evaluated by further including an interaction term between MVL and Braak stage and time, as well as by examining the association of MVL on cognitive trajectory within each Braak stage group separately.

A priori level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Programming was performed in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

2. Results

3.1. Study population and neuropathology characteristics

Sample characteristics are summarized in table 1. The mean age at enrollment and at death were 81.8 years (SD=6.2) and 89.0 years (SD=6.9), respectively. 53.2% of participants were female. 56 (90.3%) of the participants had white ethnicity, 5 (8.1%) were black and one was Hispanic. 23 Individuals met clinical criteria for dementia at their last clinical evaluation including 12 cases of probable and possible AD, 6 cases of vascular dementia (VaD) and 3 with mixed AD-VaD (Chui et al., 1992). The median interval between the last clinical evaluation and death was 1.28 years (range 0.03 to 4.76).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics based on the macroscopic vascular lesion score.

| Total Sample | Macroscopic Vascular Lesion Score a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0b | 1 or 2 | 1≥3 | p-value c | ||

| Sample size (n) | 62 | 29 | 20 | 13 | |

| Age at enrollment, mean (S.D.), years | 81.8 (6.1) | 80.1 (6.5) | 83.04(5.26) | 83.7 (6.2) | 0.190 |

| Age at death, mean (S.D.), years | 89.0(6.4) | 86.3 (6.3) | 90.06(5.37) | 93.3 (5.5) | 0.002 |

| Last visit to death, mean (S.D.), years | 1.8 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.81 (1.13) | 3.01 (1.4) | 0.001 |

| Female (%) | 33 (53.2) | 11 (37.9) | 11 (55.0) | 11 (84.6) | 0.019 |

| Education, mean (S.D.), years | 13.4 (4.0) | 13.5 (4.3) | 13.95 (3.24) | 12.2 (4.4) | 0.290 |

| Blessed score, median (range) | 2.3 (2.5) | 1.5 (2.06) | 3.0 (2.09) | 3.3 (3.6) | 0.014 |

| Pathological lesions (%) | |||||

| Large Infarcts | |||||

| 1 | 8(12.9) | - | 5 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | - |

| ≥2 | 8 (12.9) | - | 2 (10.0) | 6 (46.1) | |

| Lacunes | |||||

| 1 | 6 (9.6) | - | 2 (10.0) | 4 (30.7) | - |

| ≥2 | 6 (9.6) | - | 1 (5.0) | 5 (38.4) | |

| Leukoencephalopathy | |||||

| Mild | 12 (19.3) | - | 8 (40.0) | 4 (30.7) | - |

| Mod-severe | 11 (17.7) | - | 2 (10.0) | 9 (69.2) | - |

| Microinfarcts | 19 (30.6) | 4 (13.7) | 7 (35.0) | 8 (61.5) | 0.007 |

| Braak NFT stage, mean (S.D.) | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.1) | 0.015 |

| Cortical Lewy bodies (%) | 4 (6.4) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.3) | 0.187 |

Macroscopic vascular lesions score ranging 0–6.

Defined as absence of any macroscopic vascular lesions such as large infarcts, lacunar infarct, or leukoencephalopathy.

Using ANOVA for continuous variables, and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

3.2. Brain pathology and cognitive decline

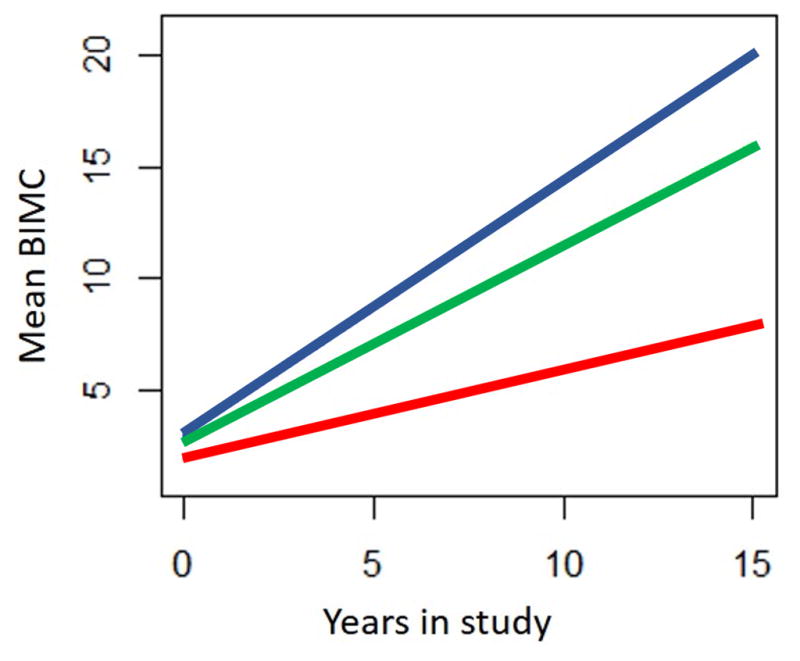

The results of the estimates of the association of vascular and AD pathology with annual rate of change in BIMC are summarized in Table 2. Models 1 and 2 are for the evaluation of MVL and Braak stage, in separate models, respectively. Compared to persons with no vascular lesions (MVL score=0), those with at more than 2 MVLs showed faster cognitive decline (difference in annual rate of change in BIMC=0.74 points/year; p=0.03). The rate of global cognitive decline for those with 1–2 MVLs was slightly faster than but not significantly different from the rate of decline among persons with no vascular lesions. Mean trajectories of BIMC in each MVL level are plotted in Figure 1. Model 2 indicated that higher Braak stage (>=3 vs <3) was associated with faster cognitive decline (difference in annual rate of decline in BIMC=0.57 points/year, p=0.003). Model 3 included both MVL and Braak stage to assess whether the effect of vascular pathology is independent of AD pathology. The difference in the rate of cognitive decline in BIMC between those with MVL score >=3 and those without vascular lesion persisted after adjustment for AD pathology (difference in rate of change in BIMC=0.68 points/year, p=0.04).

Table 2.

Association of brain pathology with rate of change in Global Cognitive Function (BIMC)

| Difference in Annual Rate of Cognitive Changea | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIMC change/yr | SE | P | BIMC change/yr | SE | p | BIMC change/yr | SE | p | |

| MVL=(1–2) vs. MVL=0 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.085 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.138 | |||

| MVL ≥ 3 vs. MVL = 0 | 0.74 | 0.34 | 0.032 | 0.68 | 0.33 | 0.042 | |||

| Braak >=3 vs. Braak< 3 | 0.57 | 0.19 | 0.003 | 0.48 | 0.17 | 0.005 | |||

All models adjusted for age at enrollment, sex and education

Model 1: MVL score modeled separately

Model 2: Braak stage modeled separately

Model 3: MVL score + Braak stage modeled simultaneously

Figure 1.

Effect of macrovascular lesion (MVL) burden on the predicted paths of global cognition measured by BIMC. Red line: predicted path of cognition in individuals with no MVL; Green line: predicted path of cognition in individuals with 1–2 MVL. Blue line: predicted path of cognition in individuals with ≥3 MVL.

Given the significantly longer duration between death and last cognitive exam for individuals with the greatest vascular burden, we re-ran the analysis with adding adjustment for time from last testing to death, and this addition did not make difference in the final outcomes (results not shown).

3.3. Interaction between Alzheimer’s pathology and Vascular pathology

There was no significant interaction between MVL and Braak stage on the rate of general cognitive decline (p=0.77), thus there was no evidence that the association of vascular pathology with cognitive decline is modified by AD pathology.

4. Discussion

In this community based clinical-pathologic study, we showed that both macrovascular lesions and AD pathology are associated with the rate of global cognitive decline. Furthermore, we observed that the effect of macrovascular brain pathology on cognitive decline persisted after adjustment for level of AD pathology.

The observation that vascular pathology is associated with rate of cognitive decline independent of AD pathology is consistent with results from other prospective autopsy series. 20–22 In the Religious Orders Study, the likelihood of dementia increased with both AD pathology and the number of macroscopic infarcts.20 The same group has also reported that microinfarcts, particularly multiple cortical microinfarcts, increased the odds of dementia independent of AD pathology.10 In the Honolulu Asia Aging study, AD and microinfarcts contributed independently to dementia risk,21 and Chui et al 22 have also reported that cerebrovascular, AD and hippocampal sclerosis each contributed independently to cognitive status. While in these studies the relation between vascular lesions and cognitive decline has been defined qualitatively (multiple lesions having a greater effect than no lesion or a single lesion), results from Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging23 showed there is a direct relation between the number of macroscopic infarcts and the odds of dementia. In line with the latter study, our results indicate higher MVLs (>2) is associated with cognitive decline independent of AD pathology.

An important question is how vascular and AD pathologies combine to cause cognitive decline. Prior clinical-pathologic studies have not yielded consistent results regarding an interaction between vascular and AD pathologies in relation to clinical cognitive performance. The Nun Study, 24 reported that cerebral infarction significantly increases the likelihood of dementia only in cases with higher levels of AD pathology. However other studies like the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging,23 the Religious Orders Study,25 and Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Aging Study26 did not observe evidence that the impact of vascular pathology depended upon extent of AD pathology with respect to cognitive function. Our data also suggest that the effect of macrovascular brain pathology on cognitive function is uniform across groups with either low or high burden of AD pathology. The disparities between prior studies might be due to differences between sample types (i.e. community vs clinical cohorts), 27 use of different pathological criteria (i.e. subcortical vs cortical vascular lesions), 23 or due to limitations of small sample size for detecting differences. These incongruent results indicate that further work in larger community-based samples is required to clarify the interaction of vascular pathology and AD pathology in relation to cognitive performance.

The current study supports that intervening on vascular risk factors may have implications for preventing or delaying cognitive decline. AD and cerebrovascular disease share common risk factors, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, insulin resistance, obesity, hyperhomocystinemia, etc., 28, 29 which are all potentially modifiable. Regardless of whether AD and vascular pathologies are additive or synergistic, these findings add to the growing body of evidence suggesting that strategies to intervene on these risk factors may reduce the risk of cognitive decline, or may slow the onset of clinical dementia.

The strengths of our study include the detailed assessment of clinical and neuropathologic data by experienced examiners, and use of validated diagnostic procedures. While our findings are promising, a few limitations should be noted. First, we do not know the temporal sequence of the pathologies prior to death, as this was a clinic-pathologic correlation study. Thus, we were not able to assess the concurrent associations of pathology with cognitive performance during antemortem follow-up. Second, neuropathologic evaluations were performed on one hemisphere. Third, identification of vascular pathology was based on gross brain sections. This is likely to have resulted in under estimation of the association between vascular lesions and clinical diagnosis of dementia. Utilization of techniques such as myelin staining of brain sections will improve quantification of white matter pathology. However, these techniques may not necessarily have clinical or imaging correlates. In this study the primary focus was on macroscopic vascular lesions and Braak staging as measures of vascular burden and AD. However other measures like microscopic vascular lesions and senile plaque burden might also play a significant role in the observed interactions. Therefore, further studies are required to clarify the role and interactions of other types of pathological lesions in cognitive decline. Finally, our sample size was relatively small, and therefor might be underpowered to detect interactions between vascular burden and NFT pathology. This small sample size also makes comparison between subgroups of dementia types difficult.

Conclusions

In summary, our study indicates that vascular pathology, a common neuropathological finding in aging subjects, increases the rate of cognitive decline independent of AD pathology. The effect of macrovascular brain pathology on cognitive function is uniform across groups with low or high burden of AD pathology.

Supplementary Material

macroscopic vascular lesions scoring system.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to thank the Einstein Aging Study staff for assistance with recruitment, and clinical and neuropsychological assessments. In addition, we appreciate all of the study participants who generously gave their time in support of this research.

Sources of Funding

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants NIA 2 P01 AG03949, NIA 1R01AG039409-01, NIA R03 AG045474, CTSA 1UL1TR001073 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), the Leonard and Sylvia Marx Foundation, and the Czap Foundation.

Footnotes

Author contributions:

Ali Ezzati: data analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, and intellectual contributions to content

Cuiling Wang: data analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript editing and intellectual contributions to content

Richard Lipton: acquisition of data, manuscript editing and intellectual contributions to content.

Dorothea Altschul: interpretation of data, manuscript editing and intellectual contributions to content

Mindy Katz: conception and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, manuscript editing, and intellectual contributions to content

Dennis Dickson: conception and design, pathologic evaluation and data acquisition, interpretation of data, manuscript editing and intellectual contributions to content

Carol A. Derby: conception and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation and intellectual contributions to content, study supervision

Conflict of interest: Authors report no conflict of interest.

Sponsor’s role: None.

Financial disclosures:

Ali Ezzati: no disclosures.

Cuiling Wang: receives research support from the National Institutes of Health [PO1 AG03949 (core leader), R03AG046504-01 (principal investigator), R01 AG039330-01 (investigator), R01AG036921 (investigator), R01 AG050448-01 (investigator), U01AG012535 (investigator).

Richard Lipton: receives research support from the NIH [PO1 AG03949 (Program Director), PO1AG027734 (Project Leader), RO1AG025119 (Investigator), RO1AG022374-06A2 (Investigator), RO1AG034119 (Investigator), RO1AG12101 (Investigator), K23AG030857 (Mentor), K23NS05140901A1 (Mentor), and K23NS47256 (Mentor), the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund; serves on the editorial boards of Neurology and Cephalalgia and as senior advisor to Headache, has reviewed for the NIA and NINDS, holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics (a company without commercial products); serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received honoraria from: Alder, Allergan, American Headache Society, Autonomic Technologies, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cognimed, Colucid, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Nautilus Neuroscience, Novartis, NuPathe, Vedanta, Zogenix.

Dorothea Altschul: No disclosures.

Mindy Katz: receives research support from NIH/NIA: P01 AG03949 (Investigator), R01 AG039409-01 (Investigator), and R03 AG045474 (Principal Investigator).

Dennis Dickson: receives research support from the NIH (P50-AG016574; P50-NS072187; P01-AG003949) and CurePSP Foundation. Dr. Dickson is an editorial board member of Acta Neuropathologica, Annals of Neurology, Brain, Brain Pathology, and Neuropathology, and he is editor in chief of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease, and International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology.

Carol Derby: receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (PO1 AG03949 (Project Leader); 2U01AG012535 (PI); 5UL1TR001073-02 (Investigator).

References

- 1.Launer LJ. Demonstrating the case that AD is a vascular disease: epidemiologic evidence. Ageing Res Rev. 2002;1:61–77. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breteler MM. Vascular risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: an epidemiologic perspective. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decarli C. Vascular factors in dementia: an overview. J Neurol Sci. 2004;226:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James BD, Bennett DA, Boyle PA, Leurgans S, Schneider JA. Dementia from Alzheimer disease and mixed pathologies in the oldest old. Jama. 2012;307:1798–1800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iadecola C, Davisson RL. Hypertension and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2008;7:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quaegebeur A, Lange C, Carmeliet P. The neurovascular link in health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neuron. 2011;71:406–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57:178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Where vascular meets neurodegenerative disease. Stroke. 2010;41:S144–146. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct pathology, dementia, and cognitive systems. Stroke. 2011;42:722–727. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strozyk D, Dickson DW, Lipton RB, et al. Contribution of vascular pathology to the clinical expression of dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1710–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verghese J, Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Lipton RB. Validity of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 1999;53:1974–1982. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz MJ, Lipton RB, Hall CB, et al. Age and sex specific prevalence and incidence of mild cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia in blacks and whites: A report from the Einstein Aging Study. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2012;26:335. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31823dbcfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grober E, Dickson D, Sliwinski MJ, et al. Memory and mental status correlates of modified Braak staging. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:573–579. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thal LJ, Grundman M, Golden R. Alzheimer’s disease: a correlational analysis of the Blessed Information-Memory-Concentration Test and the Mini-Mental State Exam. Neurology. 1986;36:262–264. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-III-R. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. Work Group to Revise DSM-III. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Task Force on DSM-IV. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society. 1980:817–838. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Cochran EJ, et al. Relation of cerebral infarctions to dementia and cognitive function in older persons. Neurology. 2003;60:1082–1088. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055863.87435.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, et al. Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chui HC, Zarow C, Mack WJ, et al. Cognitive impact of subcortical vascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:677–687. doi: 10.1002/ana.21009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Troncoso JC, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, Crain B, Pletnikova O, O’Brien RJ. Effect of infarcts on dementia in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:168–176. doi: 10.1002/ana.21413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA. 1997;277:813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2004;62:1148–1155. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118211.78503.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuropathology Group, Medical Research Council Cognitive F, Aging S. Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS) Lancet. 2001;357:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes L, Boyle P, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of older persons with and without dementia from community versus clinic cohorts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:691–701. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craft S. The role of metabolic disorders in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia: two roads converged. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:300–305. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fillit H, Nash DT, Rundek T, Zuckerman A. Cardiovascular risk factors and dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008;6:100–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

macroscopic vascular lesions scoring system.