Abstract

Background

Parent-focused Redesign for Encounters, Newborns-Toddlers (PARENT) is a well-child care (WCC) model that has demonstrated effectiveness in improving the receipt of comprehensive WCC services and reducing emergency department utilization for children ages 0–3 in low-income communities. PARENT relies on a health educator (“Parent Coach”) to provide WCC services, and utilizes a web-based pre-visit prioritization/screening tool (Well-Visit Planner; WVP), and an automated text message reminder/education service.

Objective

To assess intervention feasibility and acceptability among PARENT trial intervention participants.

Design/Methods

Intervention parents completed a survey after a 12-month study period; a 26% random sample of them were invited to participate in a qualitative interview. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using the constant comparative method of qualitative analysis; survey responses were analyzed using bivariate methods.

Results

115 intervention participants completed the 12-month survey; 30 completed a qualitative interview. Nearly all intervention participants reported meeting with the coach, found her helpful, and would recommend continuing coach-led well-visits (97–99%). Parents built trusting relationships with the coach, and viewed her as a distinct and important part of their WCC team. They reported that PARENT well-visits more efficiently used in-clinic time and were comprehensive and family-centered. Most used the WVP (87%), and found it easy to use (94%); a minority completed it at home prior to the visit (18%). 62% reported using the text message service; most reported it as a helpful source of new information and reinforcement of information discussed during visits.

Conclusion

A parent coach-led intervention for WCC for young children is a model of well-child care delivery that is both acceptable and feasible to parents in a low-income urban population.

Keywords: preventive care, well-child care, practice redesign, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Well-Child Care (WCC) visits for child preventive care during the first three years of life are critical because they may be the only opportunity before a child reaches preschool to identify and address important social, developmental, behavioral, and health issues that could have significant long-lasting effects on children’s adult lives.1 Multiple studies have demonstrated that many pediatric providers fail to provide all recommended preventive and developmental services at these visits and that most parents leave the visit with unaddressed psychosocial, developmental, and behavioral concerns.2–7

A critical problem is that the structure of WCC in the U.S. cannot support the extensive and varied needs of families. Key structural problems include (a) reliance on clinicians (pediatricians, family physicians, or nurse practitioners) for basic, routine WCC services,8–12 (b) limitation to a 15-minute face-to-face clinician-directed well-visit for the wide variety of education and guidance services in WCC,1,13,14 and (c) lack of a systematic, patient-driven method for visit customization to meet families’ needs.3,15,16 These structural problems contribute to the wide variations in processes of care and preventive care outcomes, resulting in poorer quality of WCC and perhaps worse health outcomes, particularly for children in low-income communities.4,17

We used a rigorous, structured community-engaged approach guided by key WCC stakeholders (parents, providers, and payers) and expert panel methods to develop and test a new, innovative model of WCC delivery to meet the needs of children in low-income communities:10–12,15,18,19 Parent-focused Redesign for Encounters, Newborns to Toddlers (PARENT).18 PARENT is a team-based approach to care using a health educator (“parent coach”) to provide the bulk of WCC services, address specific needs faced by families in low-income communities, and decrease reliance on the clinician as the primary provider of WCC services.

In an initial randomized controlled trial of PARENT among 251 low-income families in two urban pediatric practices, we found strong and consistent intervention effects on the quality of preventive care provided to families, and on reducing emergency department (ED) utilization.20 A question that remained for PARENT was how changing the structure and providers of a well-visit would affect parents’ WCC experiences.

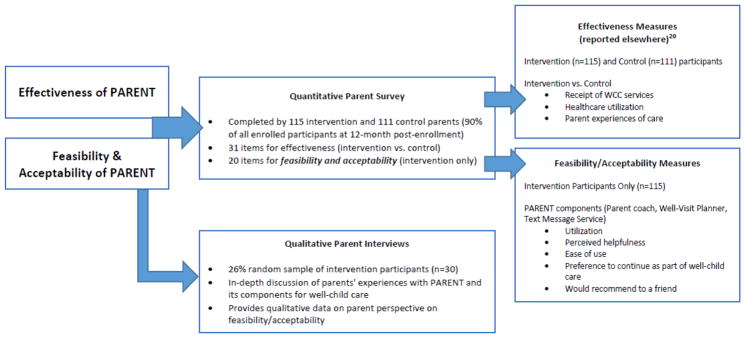

Our study objective was to understand parents’ experiences in this parent coach-based model of care, using quantitative and qualitative methods (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PARENT Trial Outcome Measures

METHODS

PARENT Intervention Components and Process

The central element of PARENT was the parent coach, a Master’s level Spanish/English bilingual, bicultural health educator, who provided anticipatory guidance, psychosocial screening and referral, and developmental/behavioral surveillance, screening, and guidance at each well-visit. The parent coach (PC) also offered “Parent Coach Call-In Time”, during which she conducted parent follow-up calls and visit reminders, and was available to answer parents’ preventive care-related questions by phone or e-mail. The PC was supported by a web-based tool, the Well-Visit Planner (WVP), for pre-visit screening, and to customize the visit to the parent’s needs; and an automated text message service to reinforce the periodic, age-specific health messages provided to families at well-visits. The WVP could be accessed at home or via a computer kiosk at the practice site, and allowed parents to 1) select Bright Futures-based anticipatory guidance priorities for their child’s well-visit, 2) complete screening questions, and 3) receive written information on anticipatory guidance topics (a publicly-available version of the parent pre-visit tool is available at www.cahmi.org/projects/wvp).21,22 Parents with a text-enabled phone and cell-phone plan were offered the text messaging service (Healthy-TXT™) at study enrollment; parents texted their child’s birthdate and clinic name to a designated number and received a welcome message from their clinic, with subsequent bi-weekly messages throughout the study. Messages focus on age-appropriate anticipatory guidance, health education, developmental tips, parent resources, and well-visit reminders. Every PARENT well-visit included a brief, problem-focused encounter with the pediatric clinician. Additional details on the PARENT intervention can be found elsewhere.20

Data Collection

English or Spanish-speaking adult parents or legal guardians of a child ≤12 months arriving at one of the two participating pediatric practices (independent, non-teaching, 6- and 2- clinician [pediatricians and physician assistants] practices) were randomized to control or intervention. Upon enrollment, parents completed a baseline survey to collect demographic data. Intervention families remained in the study for a 12-month period and received all well-visits during this time using the PARENT intervention.

Quantitative Parent Surveys

At study completion, all intervention and control parents completed a survey administered by a research assistant. In this survey, we collected data on outcome measures on receipt of WCC services to compare intervention and control participants; these outcome measures for intervention vs. control parents are reported elsewhere.20 The survey also included a series of questions for all intervention parents to assess their experience with the intervention. These survey questions asked intervention participants about each PARENT component, whether they utilized the specific components, how often they used it, its helpfulness to them, and whether they would recommend it to others (Appendix A).

First, parents were asked if they used the text messaging service (yes/no). If parents responded yes, they were asked how often they read the messages (always, usually, sometimes, never), how often they found the information in the texts helpful (always, usually, sometimes, never), and if they would recommend it to a friend (yes, no, unsure).

Next, parents were asked if they spoke with the PC, at how many well-visits they did so, how helpful they found the PC during well-visits, and if they would recommend that their pediatric clinician continue to use the PC for well-visits. Parents were also asked if they contacted the PC outside of well-visits (yes/no), how often they did so (7 categories of none to 6 or more times), the helpfulness of this contact (very helpful, helpful, somewhat helpful, not at all helpful), and if they would recommend that their pediatrician continue to make the PC available outside of well-visits (yes/no).

Finally, parents were asked about the WVP. They were asked if they completed the WVP prior to any of their well-visits (yes/no), and if so where it was completed (at home before the visit, at the clinic on day of visit, or at another location before the visit), how many well-visits it was completed for (all, some but not all visits), ease of use (very easy, easy, difficult/hard, very difficult/hard), helpfulness (very helpful, helpful, somewhat helpful, not at all), and if they would recommend that their pediatrician continue to make the WVP available (yes/no).

Parents received a $20 incentive for survey completion.

Qualitative Parent Interviews

Using computer-generated random numbers, we randomly sampled 26% of intervention participants who completed the 12-month study period and invited them to participate in a 45-minute interview focused on their experiences in receiving care with the PARENT intervention, and its components; interviews were conducted November 2014-January 2015. We used a semi-structured interview protocol, conducted by an experienced research assistant in English or Spanish, per the parent’s language preference. All interviews were conducted in person; participants received a $40 incentive upon interview completion. The interview protocol (Appendix B) included 4 main topics: parent experiences of 1) well-visits generally, 2) the PC, 3) the WVP, and 4) the text message service. Participants were first asked to describe their well-visit experiences generally with the PARENT intervention. Next, we asked participants to describe their experiences at well-visits with the PC, their child’s primary care clinician, and if and how the two worked together in providing services at the well-visit. Participants were also asked to describe their experiences in using the WVP and the text messaging services, including if and how they found each a useful component of the well-visit.

The study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board.

Analytic Methods

Quantitative Methods

We used bivariate analysis to describe intervention participant characteristics and identify how baseline characteristics may differ for intervention participants who were randomly selected to participate in a qualitative interview. Next, we examined participant quantitative survey responses on experiences with each component of the intervention, reporting responses for all intervention participants and those intervention participants selected for a qualitative interview, also identifying whether our qualitative interview participants had significantly different responses. Analyses were conducted using Stata SE 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Qualitative Methods

Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and imported into qualitative data management software (Atlas.ti 7). Three members of the research team read samples of the transcribed text and created codes for key points within the text. Through an iterative process, these codes were used to create a codebook. Two experienced coders independently and consecutively coded the full transcripts, discussing discrepancies and modifying the codebook. To measure coder consistency, we calculated Cohen’s κ using all of the quotes from the major code categories.23 Kappa scores ranged from 88% to 97%, suggesting excellent consistency.23–25

We performed thematic analysis of the 305 unique quotations covering the topics mentioned above. The analysis was based in grounded theory and performed using the constant comparative method of qualitative analysis.26 We identified salient themes, or specific concepts and ideas that emerged from the quotes within each topic, that were discussed by respondents in at least half of all interview sessions.

RESULTS

Parents (n=226) with a child ≤12 months were individually randomized to the intervention group (PARENT); 115 completed the 12-month assessment (91%). The mean index child age at enrollment was 4.2 months; 76% of parents were Latino, 21% were African American, 61% had annual household income <$20,000, and 95% of index children were Medicaid-insured (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intervention Participant Characteristics

| All Intervention Participants (n=126) | Intervention Participants Not Selected for Qualitative Interview (n=96) | Intervention Participants Selected for Qualitative Interview Sub-sample (n=30) | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | |||

| Child and Household Demographics | ||||

| Child race/ethnicity | 0.87 | |||

| Latino | 76.2 (96) | 76.0 (73) | 76.7 (23) | |

| White, non-Latino | 0.8 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Black, non-Latino | 20.6 (26) | 19.8 (19) | 23.3 (7) | |

| Other, non-Latino | 2.4 (3) | 3.1 (3) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Child age (in months) at enrollment, mean (SD) | 4.2 (3.5) | 4.1 (3.5) | 4.3 (3.3) | 0.55 |

| Gender, male | 54.0 (68) | 53.1 (51) | 56.7 (17) | 0.73 |

| Index child was first child | 34.1 (43) | 38.5 (37) | 20.0 (6) | 0.06 |

| Highest household educational attainment | 0.58 | |||

| Less than high school | 18.3 (23) | 19.8 (19) | 13.3 (4) | |

| High school/GED | 35.7 (45) | 32.3 (31) | 46.7 (14) | |

| Some college/ 2-year degree | 34.9 (44) | 36.5 (35) | 30.0 (9) | |

| ≥4-year college degree | 11.1 (14) | 11.5 (11) | 10.0 (3) | |

| Marital Status | 0.73 | |||

| Married | 34.1 (43) | 32.3 (31) | 40.0 (12) | |

| Living with partner | 35.7 (45) | 36.5 (35) | 33.3 (10) | |

| Single/Divorced | 30.2 (38) | 31.3 (30) | 26.7 (8) | |

| Annual household income | 0.56 | |||

| Under $20,000 | 61.3 (76) | 58.5 (55) | 70.0 (21) | |

| $20,000 to $34,999 | 26.6 (33) | 28.7 (27) | 20.0 (6) | |

| $35,000 or more | 12.1 (15) | 12.8 (12) | 10.0 (3) | |

| Health insurance – child | 0.29 | |||

| Medicaid | 95.2 (119) | 95.8 (91) | 93.3 (28) | |

| Private insurance | 1.6 (2) | 2.1 (2) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Uninsured | 3.2 (4) | 2.1 (2) | 6.7 (2) | |

| Household primary language English | 54.0 (68) | 55.2 (53) | 50.0 (15) | 0.62 |

| Country of birth USA | 64.3 (81) | 66.7 (64) | 56.7 (17) | 0.32 |

| Years living in US, mean (SD) | 14.4 (7.5) | 14.1 (7.1) | 15.0 (8.7) | 0.71 |

| English language proficiency | 0.68 | |||

| Very well | 63.5 (80) | 63.5 (61) | 63.3 (19) | |

| Well | 11.9 (15) | 12.5 (12) | 10.0 (3) | |

| Not well | 13.5 (17) | 14.6 (14) | 10.0 (3) | |

| Not at all | 11.1 (14) | 9.4 (9) | 16.7 (5) | |

| Child and Parent Health | ||||

| Child birth premature | 7.1 (9) | 6.3 (6) | 10.0 (3) | 0.44 |

| Child has medical problems | 4.8 (6) | 4.2 (4) | 6.7 (2) | 0.63 |

| Child takes prescription medication | 5.6 (7) | 5.2 (5) | 6.7 (2) | 0.67 |

| Child overall health rating | 0.28 | |||

| Excellent | 57.9 (73) | 54.2 (52) | 70.0 (21) | |

| Very good | 33.3 (42) | 35.4 (34) | 26.7 (8) | |

| Good/Fair/Poora | 8.7 (11) | 10.4 (10) | 3.3 (1) | |

| Parent overall health rating | 0.68 | |||

| Excellent | 26.2 (33) | 25.0 (24) | 30.0 (9) | |

| Very good | 31.0 (39) | 33.3 (32) | 23.3 (7) | |

| Good | 30.2 (38) | 30.2 (29) | 30.0 (9) | |

| Fair/Poor | 12.7 (16) | 11.5 (11) | 16.7 (5) | |

| Depressed or sad on most days for ≥ 2 years in lifetime | 19.1 (24) | 17.7 (17) | 23.3 (7) | |

| Depressed, sad, or blue for ≥ 2 weeks in past 1 year | 19.8 (25) | 19.8 (19) | 20.0 (6) | 0.98 |

| Household Functioning | ||||

| A lot of/some trouble paying for household expenses | 53.2 (67) | 53.1 (51) | 53.3 (16) | 0.98 |

| A lot of/some trouble paying for household supplies (food, formula, diapers, clothes) | 42.9 (54) | 40.6 (39) | 50.0 (15) | 0.37 |

| Help with caring for child from family members | 81.0 (102) | 83.3 (80) | 73.3 (22) | 0.22 |

GED, General Educational Development.

Fair/poor category combined with good because fair/poor category was n = 1.

P-value for comparison of responses for intervention parents that participated in a qualitative interview with those who did not participate in a qualitative interview.

Thirty parents completed a qualitative interview. There were no significant differences between parents who participated in the qualitative interviews and those who did not on baseline characteristics or on quantitative survey findings.

Experiences with Intervention

Parent Coach

Ninety-seven percent (n=112) of intervention parents reported meeting with the PC. Of these, 99% reported that the PC was helpful or very helpful during the well-visit. Ninety-seven percent would recommend that their pediatrician continue to meet with families at well-visits. Just 28 families reported contacting the PC outside of the well-visit; nearly all of these found the PC was very helpful during these contacts (93%), and all would recommend that their pediatrician continue to provide PC availability outside of scheduled well-visits (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intervention Participant Experiences- Quantitative Survey

| All Intervention Participants (n=115) | Intervention Participants Not Selected for Qualitative Interview (n=85) | Intervention Participants Selected for Qualitative Interview Participants (n=30) | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total % (N) | Total % (N)a | Total % (N) | ||

| Parent Coach | ||||

| Did parent talk to parent coach | 0.57 | |||

| Yes | 97.4 (112) | 96.5 (82) | 100.0 (30) | |

| No | 2.6 (3) | 3.5 (3) | 0.0 (0) | |

| How helpful was the parent coach | 0.80 | |||

| Very helpful | 88.4 (99) | 89.0 (73) | 86.7 (26) | |

| Helpful | 10.7 (12) | 9.8 (8) | 13.3 (4) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 0.9 (1) | 1.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Not at all helpful | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Recommend that the parent coach continue during well-child visits | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 97.3 (109) | 96.3 (79) | 100.0 (30) | |

| No | 1.8 (2) | 2.4 (2) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Missing | 0.9 (1) | 1.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

| # Of times Parent Coach Call In Time used | 0.38 | |||

| 0 | 75.7 (87) | 77.7 (66) | 70.0 (21) | |

| 1 | 13.0 (15) | 11.8 (10) | 16.7 (5) | |

| 2 | 7.8 (9) | 7.1 (6) | 10.0 (3) | |

| 3 | 2.6 (3) | 3.5 (3) | 0.0 (0) | |

| 4 | 0.9 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 3.3 (1) | |

| Call In Time helpfulness | 1.00 | |||

| Very helpful | 92.9 (26) | 89.5 (17) | 100.0 (9) | |

| Helpful | 7.1 (2) | 10.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Not at all helpful | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Should Call In Time continue | ||||

| Yes | 100.0 (28) | 100.0 (19) | 100.0 (9) | N/A |

| No | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | |

| WVP Tool | ||||

| Complete WVP tool | 0.35 | |||

| Yes | 87.0 (100) | 84.7 (72) | 93.3 (28) | |

| No | 13.0 (15) | 15.3 (13) | 6.7 (2) | |

| Where was the WVP tool completed (check all that apply) | N/A | |||

| At home before the visit | 18.0 (18) | 20.8 (15) | 10.7 (3) | |

| At the clinic on the day of the visit | 91.0 (91) | 91.7 (66) | 89.3 (25) | |

| At another location before the visit | 1.0 (1) | 1.4 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Frequency of WVP use | 0.89 | |||

| All | 56.0 (56) | 55.6 (40) | 57.1 (16) | |

| Some but not all | 44.0 (44) | 44.4 (32) | 42.9 (12) | |

| How difficult was the WVP website to use | 0.35 | |||

| Very easy | 43.0 (43) | 41.7 (30) | 46.4 (13) | |

| Easy | 51.0 (51) | 54.2 (39) | 42.9 (12) | |

| Difficult or hard | 6.0 (6) | 4.2 (3) | 10.7 (3) | |

| Very difficult/very hard | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | |

| WVP helpfulness in preparing for visit | 0.18 | |||

| Very helpful | 53.0 (53) | 58.3 (42) | 39.3 (11) | |

| Helpful | 44.0 (44) | 37.5 (27) | 60.7 (17) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 2.0 (2) | 2.8 (2) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Not at all helpful | 1.0 (1) | 1.4 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Continue having WVP available for WCC visits | 96.0 (96) | 94.4 (68) | 100.0 (28) | 0.57 |

| Text Message Service | ||||

| Parent used text message service | 61.7 (71) | 58.8 (50) | 70.0 (21) | 0.28 |

| How often did parent read text | 0.86 | |||

| Always | 86.0 (61) | 86.0 (43) | 85.7 (18) | |

| Usually | 7.0 (5) | 8.0 (4) | 4.8 (1) | |

| Sometimes | 7.0 (5) | 6.0 (3) | 9.5 (2) | |

| Never | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Parent would like to continue using text service | 94.4 (67) | 94.0 (47) | 95.2 (20) | 1.00 |

| Parent would recommend text service to a friend | 98.6 (70) | 100.0 (50) | 95.2 (20) | 0.30 |

N represents total number of responses, but is variable throughout Table 2 because it reflects the number of parents that replied “Yes” to a question

Test not performed if categories were not mutually exclusive or when all responses were identical.

In qualitative interviews, the main themes that emerged for the PC were that the PC: 1) established positive and trusting relationships with families, 2) provided useful information and guidance to families, and 3) provided social-emotional support for parents (Table 3). Parents reported that the PC was attentive to their needs during their visit (“She was always attentive, she would listen.”), effective in providing information, (“[The PC]…explained everything well.”), and helped them feel comfortable speaking with her (“At first I didn’t ask many questions because I was afraid to, but over time I began to trust her and I began to be open to asking anything.”) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Themes from Qualitative Interviews

| Themes | Frequency that topic was discussed (of 30 participant interviews) |

|---|---|

| Parent Coach | 29 of 30 |

| Established positive and trusting relationship with parents | |

| She would talk to you as a friend, like she knows you for a long time. She made me feel comfortable. ...she would remember [child’s name]. You could see when they care, and they’re friendly with you. | |

| She was open, she said… “I’m here for you any time and the website is here and you can always e-mail me, you can always call me.” It was cool. | |

| She made me feel comfortable…very welcoming. Her attitude and her way of asking you questions… noticing that she cares about what she’s asking you. | |

| Provided useful and timely information and guidance to parents | 29 of 30 |

| They gave me the right information. They gave me what I needed. When I came in, I left with what I needed to know and what my baby needed. | |

| I could ask [the parent coach] more questions. She made me feel more comfortable to ask more questions and just by knowing that I could call her any time or with any concerns that I had. It just makes it comfortable. Instead of calling the doctor here about questions concerning my daughter, I could easily call [the parent coach] and probably that would be faster. | |

| She explained a lot of things that I needed to know throughout [as my child grew]. She would answer all my questions. When he’s going to start teething, what I had to do with him, how to potty train him… how to discipline him because now he throws his tantrums. She would talk to me and she would give me written information too. I would read through that information and practice it. | |

| Provided social-emotional support for their role in parenting, and a sense of empowerment and confidence in their parenting abilities. | 24 of 30 |

| I remember that with my second son I got depression, she helped me. She gave me [resources to call], and what to do and stuff. | |

| It’s like, you had someone like a guidance counselor cause even if they asked about the kids, they asked about you as well. “So how are you doing with this? Is there anything you need help with? Are you not working? Are you not this?” It was like guidance… it was just really cool. | |

| You come to the doctor, the nurses they have their own business… They have to deal with the paperwork, checking the patient in, getting this patient a person… my parent coach --she’s focused on me for a little bit. She had a lot of people but her focus was on everyone individually as well. | |

| Well-Visit Planner | |

| Other options for accessing the WVP, such as via mobile phone, are needed. | 23 of 30 |

| [It would be better to have the WVP on the phone because] you’re always on your phone and everything is on your phone…You have your phone with you everywhere so you can easily just sign in [to the WVP… And even at the doctor you show up, “Well I wanted to ask…,” you know you can pull it up [on the phone] so it’s more handy, more organized and stuff. | |

| .. For moms like me, you know, I’m not sure how we’ll be able to do [the WVP on the computer without help]… if a mom doesn’t have [help], if her kid is running around and she wants to settle him down…there’ll have to be another way to access [the WVP], like maybe an app on our phone or something. | |

| Provided an additional source of information and guidance | 19 of 30 |

| There was no right or wrong question, right or wrong answer that you could give. It was just there to help you and guide you throughout what you needed. What you needed, instead of what they needed to know. | |

| I think, picking only three [anticipatory guidance topic priorities] at a time, I don’t think I ever felt limited because I would go through everything, and I saw what was important for me at that time. So it wasn’t like oh I can only do three questions. But it was like, what’s important for me right now, because I knew I was going to see her again. | |

| It was a different experience, because I never had [the WVP], only with my son. I think it would have been more helpful to have it [with my other kids]. I think it is more helpful because, you know, there are younger parents…I think even though they don’t say it… even me, we don’t read the information [that the doctor gives us] at times. | |

| Improved the efficiency of the visit by helping parents be more prepared for the visit | 13 of 30 |

| It helped me keep focus on what I was going to talk about, so it was good. | |

| It asks me if I have any questions that I would like to discuss with the doctor before the physical. So then it makes my job easier when I go in to see the doctor, everything is written down back there. | |

| The truth is that the first time, I was a little afraid that it would be a long process or that it would be a little complicated but even from the first time it was fast and it helped me a lot because like you said I planned my visit, all the questions that I might have, the doubts that I had. Then when I went to the appointment they were prepared to tell me. So then, I liked it. | |

| Text Message Service (HealthyTXT) | |

| Useful source of information, both new information and reinforcement/reminders of information provided during the well-visit | 18 of 30 |

| Those texts were coming in, right when I needed them. Like, “Oh I forgot about that”. Things like read to your baby, talk to her. I knew that but then I started doing that stuff more. I started talking to her more. And I started seeing different changes within her. I’m reading to her, she’s staring to point, you know things are coming to her more. | |

| When they send you the text message about your kid, they send you a link. You could click on that link and go to a website about CPR or choking, you know just anything, food, healthy foods for the baby, brushing their teeth… different websites that help you very well. | |

| Very helpful… Just information that I had forgot, I always like to know… about CPR, healthy foods, house protection, just being a better mother for my baby, safety tips. It was like, oh here goes some information, 411, you know, that kind of thing. The messages came at the right time. | |

| Well-Visits | |

| Used a team-based approach to care with parent coach and pediatrician (clinician) working as a team | 22 of 30 |

| I think it was very helpful for me, being a first time mom, and then just having the information beforehand, before seeing the doctor even because that way it gave me room that if I had questions then I could ask the doctor again. There’s always a bunch of people and stuff, so sometimes it’s hard for the doctor to stay here and talk to me for as long as I need to. So I think that’s what I liked about the parent coach. I got to talk to her and then if anything I could still talk to the doctor. It was useful for me. | |

| The doctor would tell me he needs to eat more…this is his [growth] chart… and the difference with the parent coach, she would say, “Oh do this or try to do this...” She would have more time to explain…” | |

| It was mostly health [topics] for the doctor and then with the parent coach it was like, ‘How much is she talking now, what is she doing, does she play, does she point at things? Are you reading to her? Take her on a walk so she can be outside for a while,’ and things like that. But sometimes it was similar… sometimes the doctor asked me [similar things] too like, “Oh how many words is she saying? Is she doing this? | |

| Visit time is more efficiently used with PARENT intervention | 18 of 30 |

| It was good having the parent coach there, to talk to….to help me out with certain things or questions. I got a little bit more information before the doctors came in. And it wasn’t a rushed process. It was actually taking time to talk and get my questions answered. | |

| It was an awesome… I think it’s really good. Someone sits down and tries to listen to you while you’re waiting for the doctor to come in. You’re not just waiting there you know. | |

| I just think that the time was used wisely, like okay let’s take this time to see how things are, how the baby is doing, how you’re doing, how you’re daughter is doing, and then have the doctor come in to make things more…it would flow, as an easy and fast experience. |

From the quantitative survey, we know that most families did not initiate contact with the PC outside of well-visits; however, the PC often made follow-up calls to families after the visit to check in on recommendations or community referrals made during the last visit. One parent reported (“the PC researched a facility where I could get more help…it made me feel really special…”)

Well Visit Planner

Eighty-seven percent (n=100) of participants reported completing the WVP for at least one of their well-visits. Just 18% of families reported that it was ever completed at home prior to their visit, and 91% reported that at least once it was completed at the clinic on the day of the visit. 94% reported that it was easy/very easy to use, and 97% reported that it was helpful/very helpful in preparing for their well-visit. 96% would recommend that it continue to be available for well-visits (Table 2).

In qualitative analysis, we discovered additional themes regarding the use of the WVP that highlighted some benefits and challenges for parents. While some parents reported that the WVP provided them with useful information and prepared them for the visit, (“I would do that [WVP] and I would see all the little options... I’d be like ‘oh yeah I need to ask her about this’”), most parents also reported that they would have preferred to access the tool via mobile phone, and that this lack of mobile access was a barrier to completing it on their own (“We can get out our phone and do it right there”) (Table 3).

Text Message Service

Sixty-two percent (n=71) of parents reported using the text message service; of these, 93% always/usually read the texts, and just 7% reported “sometimes” reading the texts. Of those using the text message service, 94% wanted to continue using it, and 99% would recommend it to a friend (Table 2).

Twenty-one of 30 interviewed parents enrolled and used the text message service. Of the 9 who did not, 3 reported they did not have a cell phone at the time of enrollment and one did not have an adequate text message plan. Two parents initially signed up for the text service, but did not continue to receive messages because their cell phone number changed. Most parents who used the service found the information useful (“I asked my husband if honey was bad to give to our son before he was 1 year of age, and then I got a text message the next day saying that it was bad to give babies honey before they turn one year.”) One parent, however, reported that it did not provide new information for her (“It's probably good for first-time moms…It just wasn't a fit for me because this is my third baby so I kinda knew.”) (Table 3).

Parents often interpreted the texts as coming directly from their healthcare team, although it was an automated service provided by HealthyTxt. One parent reported, “The texts that the PC would send about how the baby [grows], the car seat, different little tips… they helped me a lot.”

Well Child Care Experiences

There were no general WCC items in the quantitative survey specific to only intervention participants; findings comparing experiences of care for WCC for intervention versus control participants are reported elsewhere.20

In qualitative interviews, additional themes about the well-visits emerged (Table 3). Parents often commented on the PARENT team-based approach to care. Parents reported that the clinician and PC worked as a team, with each covering different topics for the parent. One parent commented, “The PC would come into the room when [the clinician] was seeing another patient. They were never in the room together, which I liked because I was able to have more one-on-one time with the providers”.

Parents also reported that time seemed to be more efficiently used. The PC often saw the parent prior to the clinician, using the time that would otherwise be waiting time in the exam room. One parent commented, “I think it’s really good for someone to sit down and listen to you while you’re waiting for the doctor to come in... It was within the time I was waiting to see the doctors, so it was useful to use that time instead of just waiting, because then the PC would come in and we’d talk, and then by the time the doctor came, she’d just have to see him and then I’ll be done, and the questions wouldn’t be there anymore

DISCUSSION

PARENT is a team-based approach to WCC using a health educator (“parent coach”) to provide the bulk of WCC services, address specific needs faced by families in low-income communities, and decrease reliance on the clinician as the primary provider of WCC services. We found that intervention group parents from the PARENT trial built trusting relationships with the PC over time, and viewed the PC as a distinct but important part of their WCC team.

The PC was the central element of PARENT. Other WCC interventions have used non-physician providers to enhance developmental/behavioral services within well-visits.27,28 PARENT, however, uses this non-clinical provider as the primary provider of comprehensive WCC services. There is a concern that the parents would miss out on the critical patient-provider relationship built over time,29 and perhaps that parents would not accept a non-clinical professional as the primary provider of WCC services. We found that parents built trusting relationships with the PC over time and enjoyed having an extended time to meet with the PC during the visit. Parents viewed the PC and clinician as a team, each providing separate and important aspects of the well-visit, and valued their time and relationship with both.

Few parents were ever able to complete the WVP ahead of their visit. Although the WVP could be accessed on any computer browser, it was not a mobile application and thus could not be easily navigated on a phone or tablet. Future implementation of PARENT should include mobile accessibility of the pre-visit tool to help parents independently access it prior to the well-visit. Although most study participants had mobile phone access, limited text message plans and phone number instability reduced the proportion of parents participating in the text message service. Studies of the feasibility of text messaging for immunization reminders among low-income parents report similar findings, including 74% of parents with an unlimited text plan,30 and 12% with an undeliverable/wrong number.31

We found that intervention participants viewed the PARENT intervention as efficiently utilizing their wait time during their visit. This was accomplished by utilizing the waiting time spent in the exam room awaiting the clinician as an opportunity to meet with the PC and receive the bulk of WCC services. Parents also utilized wait time in the waiting room by completing the WVP, which prepared them for the visit. In essence, there was less idle wait time during the visit, both in the waiting room and in the exam room.

There are several study limitations. We were only able to include data on intervention group parents who completed the study through the 12-month survey. Intervention parents who dropped out of the study or who we were unable to reach may have important experiences with the intervention that we cannot report. However, this was a small minority of intervention parents; 91% of enrolled intervention parents completed the 12-month assessment. As this paper focuses on parent experiences with the intervention, we do not present control group data; an intervention versus control group analysis is presented elsewhere.20 Social desirability bias may also limit our findings; to reduce this type of bias, all quantitative and qualitative surveys were conducted privately with a research assistant who was not directly involved in the intervention and not affiliated with the pediatric practices. Additionally, the intervention experiences of participants were highly influenced by the PC. The study utilized one PC shared by the two participating practices; it is not clear if intervention experiences can be replicated across other “parent coaches” or other pediatric practices. This is particularly relevant as intervention parents rated the parent coach highly—it is unclear to what extent the positive experiences with the PARENT intervention could be related to the parents’ personal relationship with the PC, as opposed to the content of the PARENT intervention well-visits. A larger study utilizing multiple PCs will help to elucidate this important question. Finally, there are financial and logistical challenges to implementing PARENT that we do not address here, including availability of exam rooms, visit efficiency, staffing costs, and how to bring the intervention to scale for a clinic or practice.

In conclusion, we found that a parent coach-led intervention for WCC for young children is a model of well-child care delivery that is both acceptable and feasible to parents in a low-income urban population. Parents readily accepted and built relationships with the parent coach, who provided the bulk of services within WCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23-HD06267), Health Resources and Services Administration (R40-MC21516), and the UCLA Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Equity.

Abbreviations

- WCC

well-child care

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Trial Registration: NCT02262962; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02262962

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Contributors' Statement N.A. Mimila made substantial contributions to drafting the manuscript, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

P.J. Chung, M.N. Elliott, and C.D. Bethell made substantial contributions to conception and design, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Y. Bruno and T. Chavis made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

C. Biely made substantial contributions to data analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

S. Chacon, S. Contreras, and T. Moss made substantial contributions to the acquisition and analysis of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

T.R. Coker conceptualized and designed the study; led data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the initial manuscript; and approved the final manuscript as submitted. She had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan P, editors. Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuster M, Duan N, Regalado M, Klein D. Anticipatory guidance: What information do parents receive? What information do they want? Arch Pediatr Adol Med. 2000;154:1191–1198. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.12.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bethell C, Reuland CH, Halfon N, Schor EL. Measuring the quality of preventive and developmental services for young children: National estimates and patterns of clinicians' performance. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6 Suppl):1973–1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung PJ, Lee TC, Morrison JL, Schuster MA. Preventive care for children in the United States: Quality and barriers. Ann Rev Public Health. 2006;27:491–515. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halfon N, Regalado M, Sareen H, et al. Assessing development in the pediatric office. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6 Suppl):1926–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bethell C, Reuland C, Schor E, Abrahms M, Halfon N. Rates of parent-centered developmental screening: disparities and links to services access. Pediatrics. 2011 Jul;128(1):146–155. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson LM, Inkelas M, Halfon N, Schuster M, O'Connor KG. Overview of the content of health supervision for young children: Reports from parents and pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6 Suppl):1907–1916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Council on Pediatric Practice. Standards of Child Health Care. Evanston, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coker TR, Thomas T, Chung PJ. Does well-child care have a future in pediatrics? Pediatrics. 2013 Apr;131(Suppl 2)(S1):S149–159. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0252f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coker TR, Windon A, Moreno C, Schuster MA, Chung PJ. Well-child care clinical practice redesign for young children: a systematic review of strategies and tools. Pediatrics. 2013 Mar;131(Suppl 1)(Supplement 1):S5–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1427c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mooney K, Moreno C, Chung PJ, Elijah J, Coker TR. Well-child care clinical practice redesign at a community health center: provider and staff perspectives. J Prim Care Community Health. 2014 Jan 1;5(1):19–23. doi: 10.1177/2150131913511641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coker T, Casalino LP, Alexander GC, Lantos J. Should our well-child care system be redesigned? A national survey of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):1852. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine and Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule Workgroup. Policy Statement: 2014 Recommendations for Pediatric Preventive Health Care. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):568–570. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halfon N, Stevens GD, Larson K, Olson LM. Duration of a well-child visit: association with content, family-centeredness, and satisfaction. Pediatrics. 2011 Oct;128(4):657–664. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coker TR, Chung PJ, Cowgill BO, Chen L, Rodriguez MA. Low-income parents' views on the redesign of well-child care. Pediatrics. 2009 Jul;124(1):194–204. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radecki L, Olson LM, Frintner MP, Tanner JL, Stein MT. What do families want from well-child care? Including parents in the rethinking discussion. Pediatrics. 2009 Sep;124(3):858–865. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belamarich PF, Gandica R, Stein REK, Racine AD. Drowning in a Sea of Advice: Pediatricians and American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statements. Pediatrics. 2006 Oct;118(4):e964–e978. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coker TR, Moreno C, Shekelle PG, Schuster MA, Chung PJ. Well-child care clinical practice redesign for serving low-income children. Pediatrics. 2014 Jul;134(1):e229–239. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coker TR, DuPlessis HM, Davoudpour R, Moreno C, Rodriguez MA, Chung PJ. Well-child care practice redesign for low-income children: the perspectives of health plans, medical groups, and state agencies. Acad Pediatr. 2012 Jan-Feb;12(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coker TR, Chacon S, Elliott MN, et al. A Parent Coach Model for Well-Child Care Among Low Income Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20153013. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bethell C. MCH Library. Health Resources and Services Administration; 2012. Patient centered quality improvement of well-child care (Project Number R40MC08959) http://www.mchlibrary.info/MCHBfinalreports. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Inititiative. [Accessed February 6, 2014];Well-Visit Planner. 2014 http://www.cahmi.org/projects/wvp.

- 23.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis J, Koch G. Measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakeman R, Gottman J. Observing Interaction: An Introduction to Sequential Analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minkovitz CS, Hughart N, Strobino D, et al. A practice-based intervention to enhance quality of care in the first 3 years of life: The Healthy Steps for Young Children Program. JAMA. 2003;290:3081–3091. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.23.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendelsohn A, Dreyer B, Flynn V, et al. Use of Videotaped Interactions During Pediatric Well-Child Care to Promote Child Development: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2005;26(1):34–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furman L. Changing the model for well child care – how can we serve families better? [Accessed April 27, 2016];AAP Journals Blog. 2016 http://www.aappublications.org/news/2016/02/23/well-child-care-pediatrics-0216.

- 30.Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Chesser A, Hart T, Paschal A, Nguyen T, Wittler RR. Text messaging immunization reminders: feasibility of implementation with low-income parents. Prev Med. 2010;50(5):306–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, Vargas CY, Vawdrey DK, Camargo S. Effect of a text messaging intervention on influenza vaccination in an urban, low-income pediatric and adolescent population: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307(16):1702–1708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.