Abstract

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was expected to benefit patients with substance use disorders, including opioid use disorders (OUDs). This study examined buprenorphine use and health services utilization by patients with OUDs pre- and post-ACA in a large health care system.

Methods

Using electronic health record data, we examined demographic and clinical characteristics (substance use, psychiatric and medical conditions) of two patient cohorts using buprenorphine: those newly enrolled in 2012 (“pre-ACA”, N=204) and in 2014 (“post-ACA”, N=258). Logistic and negative binomial regressions were used to model persistent buprenorphine use, and to examine whether persistent use was related to health services utilization.

Results

Buprenorphine patients were largely similar pre- and post-ACA, although more post-ACA patients had a marijuana use disorder (p<.01). Post-ACA patients were more likely to have high deductible benefit plans (p<.01). Use of psychiatry services was lower post-ACA (IRR: 0.56, p<.01), and high deductible plans were also related to lower use of psychiatry services (IRR: 0.30, p<.01).

Conclusion

The relationship between marijuana use disorder and prescription opioid use is complex, and deserves further study, particularly with increasingly widespread marijuana legalization. Access to psychiatry services may be more challenging for buprenorphine patients post-ACA, especially for patients with deductible plans.

Keywords: Affordable Care Act, buprenorphine, health services utilization

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) (U.S. Congress 2010) aimed to provide greater insurance coverage and increased access to treatment for individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs) (Watkins et al. 2015; McLellan and Woodworth 2014). To that end, the ACA included SUD treatment as an essential benefit, removed pre-existing conditions criteria for health insurance coverage, and expanded Medicaid eligibility criteria (U.S. Congress 2010). Prior to its implementation in 2014, expectations were high regarding the ACA’s positive impact on SUD-affected populations and treatment availability (Mark et al. 2015; McLellan and Woodworth 2014), but little quantitative data have yet emerged post ACA implementation.

Implementation of these key elements of the ACA occurred at the same time as the opioid epidemic was reaching full force in the United States, with increased rates of opioid misuse and overdose. From 1992 to 2012, the number of Americans who reported abusing prescription opioids nearly tripled (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2013), and in 2014, more than 18,000 people had a fatal overdose related to prescription opioids, exceeding four times the 1999 number (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Health Statistics 2015). The opioid epidemic’s impact underscores the growing need for the treatment for opioid use disorders (OUD), and the increased insurance coverage resulting from the ACA (Uberoi, Finegold, and Gee 2016) may contribute to increased demand. Buprenorphine opioid agonist treatment for OUD is effective, with longer duration of use related to improved substance use outcomes (Weiss et al. 2011). Yet expanding access to buprenorphine medication for OUD has remained a challenge, with a modest 37–53% of substance use treatment providers offering it (Andrews et al. 2014; Knudsen, Abraham, and Roman 2011). Factors such as stigma, provider availability and willingness to prescribe, certification requirements and inadequate institutional support have limited widespread use (Volkow et al. 2014; Hutchinson et al. 2014). Whether use of buprenorphine for OUD increased after the ACA was implemented, given increased insurance coverage and the concurrent opioid epidemic, has not been examined within health systems.

In addition to SUD treatment needs, patients with OUD have high psychiatric and medical comorbidity (Bahorik et al. 2016; Martins et al. 2012; Mertens et al. 2003), and are more likely to use health services, such as the emergency department (ED) (Frank et al. 2015; Kerr et al. 2005; Macias Konstantopoulos et al. 2014). There were expectations that patients newly enrolled through the ACA might have even higher medical severity and greater comorbidity, as a significant portion were previously un- or under-insured (Chokshi, Chang, and Wilson 2016; Reichard August 4, 2014). These individuals could have unmet health care needs and pent up demand resulting in increased use of health services. However, patients with OUD who are maintained on buprenorphine may have higher functioning and improved health, and potentially more appropriate use of health services. For example, three recent studies indicated that patients with longer retention on buprenorphine had lower likelihood of using expensive services such as the ED and hospitalizations (Schwarz et al. 2012; Lo-Ciganic et al. 2016; Tkacz et al. 2014). Thus, while buprenorphine patients are likely to have multiple health service needs, effective OUD treatment could lead to lower service utilization over time.

This study examined changes associated with buprenorphine/naloxone (hereafter referred to as “buprenorphine”) use pre- and post- ACA implementation in a large health system. In addition, we examined factors associated with persistent use of buprenorphine (defined as continuous days of use), and whether persistent use is related to the utilization of different types of health care services. We hypothesized that: 1) buprenorphine use would increase among health system enrollees post-ACA; 2) buprenorphine patients enrolled post-ACA would have greater psychiatric and medical comorbidity, 3) patients would have longer buprenorphine persistence post-ACA, and 4) longer persistence would be related to lower likelihood of ED, primary care, and psychiatry services, and greater use of SUD treatment services for both cohorts.

Methods

Setting

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is an integrated health care system serving approximately 3.9 million members (approximately 45% of the commercially insured population in the region) and provides integrated medical and SUD treatment, which is available to all members without referral. The membership is racially and socio-economically diverse and highly representative of the demographic characteristics of region (Gordon 2006).

Buprenorphine treatment

In KPNCs integrated system, buprenorphine is provided through its specialty outpatient SUD treatment programs rather than in primary care. In these programs, the predominantly group-based SUD treatment philosophy is based on total abstinence from non-medical use of prescription drugs including opioids. Group sessions include supportive therapy, health education, relapse prevention and family-oriented therapy; the intensity of the program attendance varies by patient need. Individual counseling, physician appointments, and pharmacotherapy are available as needed (Satre et al. 2004). Patients are prescribed buprenorphine based on clinical need, and no limit is placed on the duration of use. In order to receive buprenorphine, patients must attend the SUD program treatment sessions. This requirement has not changed between the pre- and post-ACA time periods.

Sample

The study goal was to compare new members pre- and post-ACA who used buprenorphine for OUD. Using data from the KPNC electronic health record (EHR), we selected adults (ages 18–64) who were newly enrolled in KPNC between 1/1/2012–12/31/2012, and who used buprenorphine, as the “pre-ACA” sample (N=204). The “post-ACA” sample were new members enrolled between 1/1/2014–12/31/2014, and who used buprenorphine (N=258). We chose to examine new enrollees, anticipating that differences between the pre- and post-ACA period would be more visible among first-time enrollees than in the overall health plan membership. New members were defined as not being enrolled in KPNC in the prior six months. Buprenorphine use was defined as filling at least one buprenorphine prescription within 1 year of enrollment. To ensure patients were using buprenorphine for opioid addiction (vs. only for pain), they also were required to have an opioid dependence diagnosis [International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) code: 3040, 3047, 3055] within 6 months prior to or following the buprenorphine prescription fill date. The first buprenorphine prescription was chosen as the index prescription for all subsequent analysis.

Measures

Measures included in the models were selected based on the literature and potential relationship to the outcomes of medication persistence and health services utilization (Andersen, Davidson, and Baumeister 2014; Zeber et al. 2013). Demographic data (sex, age and race/ethnicity) were obtained from the EHR. ICD-9 diagnoses within 6 months of the index buprenorphine prescription were grouped into: a) medical comorbidities that have been shown to be high cost and/or substance use related (chronic pain including lower back pain, arthritis/osteoporosis, hypertension, asthma, Hepatitis B and C, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, HIV, pneumonia, cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD)) (Mertens et al. 2008; Ray et al. 2000); b) psychiatric disorders that are most prevalent and/or regulated by California parity law (major depression, anxiety, developmental disorders, eating disorders, personality disorders, obsessive compulsive and panic disorders, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia) (California Department of Managed Health Care 2016); and c) SUDs included alcohol and drug use disorders (tobacco, marijuana, sedatives, amphetamines, and cocaine). We created three dichotomous indicators indicating the presence/absence of medical comorbidity, psychiatric comorbidity, and substance use disorder diagnoses within 6 months post-index buprenorphine prescription date.

We controlled for type of insurance coverage and plan deductible level since these can impact health services utilization (Andersen, Davidson, and Baumeister 2014; Wharam et al. 2011; Waters et al. 2011), and because deductible plans are key features of the ACA-mandated health benefit plans available on the state health insurance exchange. Type of insurance coverage was stratified by Commercial, Medicaid, and other (e.g., other government subsidy programs), ascertained from the KPNC membership database. Deductible plan limits were classified into 3 levels (none, 1–$999 and ≥ $1000) (Satre et al. 2016).

For the post-ACA cohort, we obtained data on who enrolled through the state insurance exchange and their tiered metal plan status (Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Platinum); members’ cost-sharing (e.g., co-payments and deductibles) decreases with the rise from Bronze to Platinum (Covered California 2016).

Health service utilization data in the 6 months post-index buprenorphine prescription date were obtained from the EHR and included any ED, primary care, psychiatry and substance use treatment visits. We created a dichotomous indicator of any ED use, and continuous measures of the number of primary care, psychiatry and substance use treatment visits during this period.

Buprenorphine persistence reflects the duration of time from index buprenorphine prescription to discontinuation as a measure of continuous days. We first calculated the number of days from index buprenorphine date to discontinuation allowing for a gap of 30 days between prescription refills (Kaur, McQueen, and Jan 2008) or the end of follow-up time (180 days). Using this, we defined a dichotomous measure of persistence (= 1 if ≥80%, 0 otherwise) as has been done in other studies (Benner et al. 2002; Caetano, Lam, and Morgan 2006).

Statistical Analyses

We compared characteristics between the pre- and post-ACA buprenorphine samples using chi-square tests of bivariate frequencies for categorical variables such as gender, race/ethnicity, presence of any comorbidity as well as by specific types of comorbidity (e.g., depression, asthma), and t-tests for continuous measures such as age. We also examined our measure of persistence between the pre- and post-ACA buprenorphine cohorts using chi-square.

We used logistic regression models to compare medical and psychiatric comorbidity rates between the pre- and post-ACA cohorts, controlling for age, gender and race/ethnicity. The coefficient of interest was an indicator variable for cohort (post-ACA=1).

Using regression models with an indicator variable for cohort (post-ACA=1) and pooling the two samples, we then examined whether the pre- and post-ACA buprenorphine cohorts had different likelihood of buprenorphine persistence, controlling for demographic factors, comorbidity, substance use, deductible levels, and length of enrollment in the health plan (number of member months). Finally, we modeled the relationship between buprenorphine persistence using the dichotomous measure, and health services used in the six months post-index buprenorphine use (e.g., after the first prescription), controlling for demographics, comorbidity, substance use, deductible levels, and the length of enrollment in the health plan. We used logistic regression for ED use, and negative binomial regression (which is a generalization of the Poisson distribution) for primary care, substance use and psychiatry services use since the distribution of those visits was over-dispersed. The exponent of the coefficient of each covariate represents the incident rate ratio relative to the reference group. In these service utilization models, the key coefficient of interest was that of the indicator variable for buprenorphine persistence (defined above). All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4®.

Results

Demographics

The percentage of OUD patients receiving buprenorphine did not change significantly between the pre- and post- ACA time periods (22.8% vs. 23.9% respectively, not shown); subsequent post hoc analyses showed no change in the percentage of OUD patients in the overall membership. The pre- and post-ACA buprenorphine cohorts had similar gender (63.2% vs. 64.7% male) and race/ethnicity (79.9% vs. 77.1% whites) distributions (Table 1). The post-ACA cohort was older (36.4 vs. 33.9 years, p < .05. The post-ACA cohort was more likely to have a high deductible (≥$1,000) benefit plan than the pre-ACA cohort (21.7% vs. 13.2%; p < .01). Whereas the pre-ACA cohort was all commercially insured, 8.4% of the post-ACA cohort was enrolled in Medicaid or other non-commercial products. Of the post-ACA cohort, 13.9% were enrolled through the exchanges; with 91.3% of those in the lower cost-sharing silver, gold or platinum plans (not shown).

Table 1.

Demographic Comparison Between Pre- and Post-ACA Buprenorphine Cohorts

|

Pre-ACA (N=204) |

Post-ACA (N=258) |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 129 | 63.2% | 167 | 64.7% | 0.74 |

| Female | 75 | 36.8% | 91 | 35.3% | |

| Age | |||||

| < 30 | 93 | 45.6% | 95 | 36.8% | 0.20 |

| 30–39 | 57 | 27.9% | 70 | 27.1% | |

| 40–49 | 25 | 12.3% | 48 | 18.6% | |

| 50–59 | 25 | 12.2% | 37 | 14.4% | |

| => 60 | 4 | 2.0% | 8 | 3.1% | |

| Mean Age (years) | 34 | 36 | 0.02 | ||

| (SE) | (0.80) | (0.71) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 163 | 79.9% | 199 | 77.1% | 0.83 |

| Black | 8 | 3.9% | 13 | 5.0% | |

| Asian | 5 | 2.5% | 4 | 1.6% | |

| American Indian/Native Hawaiian | 1 | 0.5% | 2 | 0.8% | |

| Hispanic | 27 | 13.2% | 40 | 15.5% | |

| Deductible Levela | |||||

| None | 158 | 83.6% | 149 | 64.8% | < .01 |

| $1 – $999 | 6 | 3.2% | 31 | 13.5% | |

| => $1000 | 25 | 13.2% | 50 | 21.7% | |

| Business Linea | |||||

| Commercial | 189 | 100.0% | 219 | 91.6% | < .01 |

| Medicaid | 0 | 0.0% | 17 | 7.1% | |

| Other | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 1.3% | |

| Exchange Members | NA | 32 | 13.9% | ||

Ns do not add up to 204 and 258 due to missing values.

Comorbidity

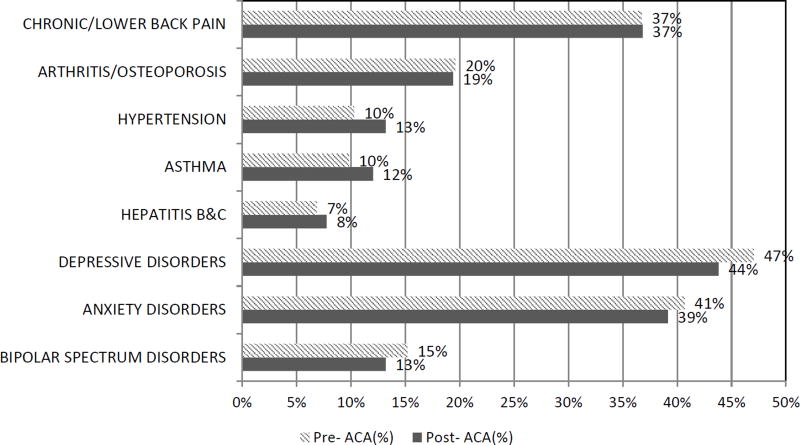

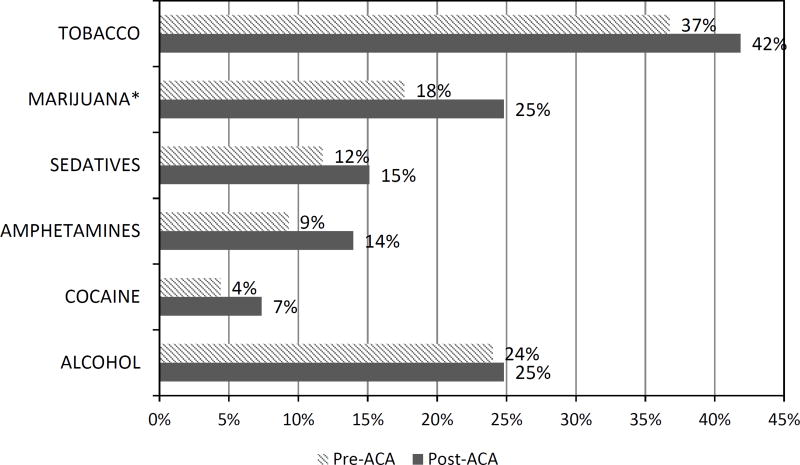

There were no differences between the pre- and post- ACA cohorts for either medical or psychiatric comorbid conditions (Figure 1). The post-ACA buprenorphine cohort had higher marijuana use (25% vs. 18%, p<.05) than the pre-ACA cohort (Figure 2). Alcohol use disorder was similar between the two groups (p >.05).

Figure 1. Medical and Psychiatric Comorbidity Pre and Post ACA among Buprenorphine Patients.

Notes: N= 204 in the pre-ACA cohort and N=258 in the post-ACA cohort.

CVD, cancer, and pneumonia are not presented because of low numbers (<1%).

Developmental, eating, obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, and panic disorders are not presented due to low numbers (<5%)

Figure 2. Substance Use Diagnoses Pre and Post ACA among Buprenorphine Patients.

*p<.05

Notes: N= 204 in the pre-ACA cohort and N=258 in the post-ACA cohort.

Persistence

The percentage of buprenorphine patients who were persistent for at least 80% of the six-month interval following index buprenorphine prescription did not differ between the pre- and post-ACA cohort (38.0% vs. 35.8%; p = 0.62) nor did the mean number of days of continuous buprenorphine persistence (95.8 days vs. 92.3 days; p = 0.59) (results not shown). Our regression model of buprenorphine persistence did not indicate any difference between the pre- and post- ACA samples (not shown). Older individuals were more likely to be persistent (OR: 1.04, p<.01).

Health Services Use

Finally, we examined the relationship between buprenorphine persistence and services use in the 6 months post-index buprenorphine prescription (Table 2). Controlling for age, gender, race, substance use, psychiatric and medical comorbidity, and deductibles, the post-ACA cohort was less likely than pre-ACA cohort to use psychiatry services [(Incident Rate Ratio (IRR): 0.56, p<.05)]. There was no difference between the pre- and post-ACA cohorts for ED, primary care, or substance use treatment services.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Health Services Utilization Among Buprenorphine Patients 6 Months After Index Prescription

| Variable | ED | Primary Care |

SU Treatment |

Psychiatry | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P- value |

IRR | 95% CI | P- value |

IRR | 95% CI | P- value |

IRR | 95% CI | P- value |

|

| Post-ACA | 0.86 | (0.53,1.38) | 0.52 | 1.07 | (0.81,1.40) | 0.63 | 1.16 | (0.87,1.55) | 0.32 | 0.56 | (0.37,0.85) | 0.01 |

| (Ref: Pre-ACA) | ||||||||||||

| Age | 1.03 | (1.00,1.05) | 0.04 | 1.02 | (1.01,1.03) | <.01 | 0.99 | (0.97,1.00) | 0.07 | 1.00 | (1.02,1.19) | 0.68 |

| Gender | 1.01 | (0.61,1.68) | 0.96 | 2.13 | (1.62,2.80) | <.01 | 1.32 | (0.97,1.80) | 0.08 | 1.74 | (1.15,2.61) | 0.01 |

| (Ref: Male) | ||||||||||||

| White | 0.64 | (0.37,1.11) | 0.11 | 0.86 | (0.62,1.19) | 0.37 | 0.77 | (0.54,1.08) | 0.13 | 1.36 | (0.79,2.34) | 0.27 |

| (Ref: Non-white) | ||||||||||||

| Medical Dx | 1.90 | (1.14,3.17) | 0.01 | 1.43 | (1.07,1.93) | 0.02 | 0.84 | (0.60,1.16) | 0.28 | 1.25 | (0.82,1.89) | 0.30 |

| (Ref: None) | ||||||||||||

| Psychiatric Dx | 1.27 | (0.742,2.17) | 0.38 | 1.31 | (0.96,1.78) | 0.08 | 1.09 | (0.80,1.50) | 0.58 | 12.69 | (6.93,23.24) | <.01 |

| (Ref: None) | ||||||||||||

| Alcohol Dx | 0.81 | (0.47,1.40) | 0.45 | 1.21 | (0.88,1.66) | 0.25 | 1.45 | (1.04,2.03) | 0.03 | 0.61 | (0.37,1.00) | 0.05 |

| (Ref: None) | ||||||||||||

| Tobacco Dx | 2.70 | (1.66,4.37) | <.01 | 1.20 | (0.91,1.59) | 0.19 | 1.47 | (1.09,1.97) | 0.01 | 1.51 | (0.98,2.32) | 0.06 |

| (Ref: None) | ||||||||||||

| Non-Opioid Drug Dx | 2.49 | (1.48,4.16) | <.01 | 0.97 | (0.73,1.30) | 0.85 | 1.76 | (1.31,2.34) | <.01 | 1.09 | (0.71,1.67) | 0.69 |

| (Ref: None) | ||||||||||||

| Persistence | 0.66 | (0.40,1.09) | 0.10 | 0.87 | (0.65,1.16) | 0.33 | 1.65 | (1.24,2.21) | <.01 | 1.23 | (0.81,1.87) | 0.34 |

| Low Deductible | 0.49 | (0.19,1.30) | 0.69 | 0.64 | (0.39,1.06) | 0.08 | 1.36 | (0.64,1.32) | 0.23 | 0.30 | (0.11,0.78) | 0.01 |

| High Deductible | 0.60 | (0.31,1.17) | 0.37 | 0.42 | (0.28,0.62) | <.01 | 0.92 | (0.83,2.22) | 0.65 | 0.30 | (0.16,0.58) | <.01 |

| (Ref: None) |

Notes: Dx is Diagnosis, OR is Odds Ratio, IRR is Incidence Risk Ratio, CI is Confidence Interval, ED is Emergency Department, SU is Substance Use

Individuals who were persistent showed a trend of being less likely to use the ED (OR: 0.66 p=.10). While persistence did not have a significant effect on primary care or psychiatry services use, those who were persistent had 65% higher SU treatment visit rate (IRR: 1.65, p < .01).

Individuals with psychiatric comorbidities had greater use of psychiatric services (IRR: 12.69, p<.001). Those with medical comorbidities were more likely to have higher use of ED (OR: 1.90, p<.05) and primary care services (IRR: 1.43, p<.05). Those with alcohol use disorders were likely to use more substance use treatment services (IRR: 1.45, p<.05), but less psychiatry services (IRR: 0.61, p<.05). Those who used tobacco were likely to have used more ED services (OR: 2.70, p<.01), substance use treatment services (IRR: 1.47, p<.05) and a trend toward more psychiatry services (IRR: 1.55, p=.06). Non-opioid drugs disorders were associated with higher use of ED services (OR: 2.49, p<.01), and substance use treatment services (IRR: 1.76, p<.01). Those with either lower ($1–999) or higher (≥$1,000) deductibles were less likely to use primary care or psychiatry services than those with no deductible (p value range=<.01–<.10).

Discussion

The ACA raised hopes for increased treatment access for patients with SUDs, including those with OUDs, although few studies have empirically examined the ACA’s impact. The current study compared differences in patient characteristics and health care services use among patients treated with buprenorphine for OUD before and after the 2014 ACA implementation. Overall, we expected that post-ACA buprenorphine patients would be more complex with more medical and psychiatric comorbidity and SUDs than pre-ACA buprenorphine patients. However, the two cohorts were largely similar, with the exception of more post-ACA patients with marijuana use disorders. It is possible that post-ACA patients were less experienced navigators of the health system, and additional differences in complexity have not yet appeared. Alternatively, new patients post-ACA may not be as complex as was expected and/or did not have the pent-up demand related to medical and psychiatric conditions. We know of no changes in health system policy that might impact findings.

The increase in marijuana use disorder suggests that SUD treatment programs, other health providers, and health systems should anticipate the potentially greater needs of patients related to marijuana use problems. Observational evidence from state level data have suggested that medical marijuana use is related to lower rates of opioid misuse and overdose (Powell and Pacula November 2015). A recent survey found that patients with pain using medical marijuana had 64% lower use of prescription opioids (Boehnke, Litinas, and Clauw 2016). However, distinguishing misuse from medical use of marijuana may be critical in interpreting these findings. The relationship between marijuana use disorder and prescription opioid use is complex, and needs further study, particularly in an environment of increasingly widespread marijuana legalization.

Given that the growing impact of the opioid epidemic was largely concurrent with implementation of the ACA, we expected to find an increase in buprenorphine patients post-ACA, but this did not occur. Buprenorphine is a critical tool for the treatment of OUD, one that has been underutilized across all systems of care (Jones et al. 2015). It is effective for many OUD patients, particularly when long-term use is maintained (Weiss et al. 2011; Mattick et al. 2008; Nielsen et al. 2016). Federal agencies such as NIDA and SAMHSA have strongly supported the use of buprenorphine, as have clinical guidelines (Kampman and Jarvis 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 2016; National Institute on Drug Abuse 2016). OUD patients were no more likely to be prescribed buprenorphine post-ACA, and post hoc analyses indicated no increase of OUD patients in the overall membership, even in an environment of heightened awareness of the opioid epidemic. One potential systemic reason is that buprenorphine prescribing at KPNC was already fairly broad (relatively) in the pre-ACA time frame. Approximately 23% of OUD patients in both cohorts had been prescribed buprenorphine which, although not high, is greater than the national average of 10% percent of patients who need SUD treatment subsequently receiving it (Han et al. September 2015).

Barriers to prescribing buprenorphine are widely acknowledged (Roman, Abraham, and Knudsen 2011; Volkow et al. 2014). Although the ACA can help open the door to improved access by increasing insurance coverage for people in need, it does not remove other barriers to buprenorphine use such as stigma and cost. Opioid agonist therapy has a long history of social stigma (Yarborough et al. 2016). Not all patients are open to taking a medication for OUD and it is possible that this reluctance may have intensified in the post-ACA timeframe. Anecdotal information from our clinical partners suggests that, with the opioid epidemic and increased negative reporting in the media recently about opioids, some patients are reluctant to take buprenorphine, possibly due to heightened stigma and concerns that their dependence problems started with a prescribed medication.

Treatment cost could also be higher for post-ACA OUD patients, given the increase in deductible plans post-ACA. Buprenorphine patients at KPNC are required to attend SUD treatment programs, which can be intensive and costly for patients with deductible plans. Significantly more patients post-ACA had deductible benefit plans, which is not surprising given the ACA’s reliance on these types of plans in the state’s health insurance marketplace.

This shift in cost structure raises concern about access to services given that high deductible plans have been related to decreased use of appropriate health care utilization (Beeuwkes Buntin et al. 2011; Galbraith et al. 2012). Deductibles were not related to lower use of substance use treatment, at least among patients already using buprenorphine. However, it is possible that patients with deductible plans decided to not start buprenorphine, once they became aware of the costs of treatment. While for the most part health services utilization did not differ pre- or post- ACA, the post-ACA cohort did have lower use of psychiatry services. Although these data do not allow us to ascertain patient need, the post-ACA cohort did not have a correspondingly lower prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses. However, having a higher deductible was related to lower use of psychiatric services, which may reflect greater elasticity of demand in response to costs (Wells, Keeler, and Manning 1990).

Other potential reasons for the lower use of psychiatry services could be that post-ACA new member patients were more unfamiliar with the health system, which impacted access to specialty services such as psychiatry. For some OUD patients, the requirement that they attend multiple group treatment sessions in SUD programs may have reduced motivation to access additional services in psychiatry. Previous research with HIV patients in this health system examined services use pre- and post-ACA and did not find lower use of psychiatry services (Satre et al. 2016). The reason for the difference is not clear, although HIV patients typically have a specialty HIV primary care clinic as their medical home, which may provide greater coordination with specialty services such as psychiatry.

Persistent buprenorphine use was related to greater use of SUD treatment services, which is understandable since this is where patients were prescribed buprenorphine. Although a trend, patients with persistent use of buprenorphine were less likely to use the ED, with one interpretation being that they were more stable in terms of their health and in less need of ED services. This is consistent with prior literature, and in addition to improved patient outcomes, would be a benefit to health systems (Schwarz et al. 2012; Lo-Ciganic et al. 2016; Tkacz et al. 2014). Although it is not possible with the present data, it is important to examine the relationship of persistent use of buprenorphine over the longer term to services utilization and other outcomes, since little is known about patients who use buprenorphine over the long term.

Limitations

As with most studies that examine medication use with EHR data, these results reflect dispensed medications since we do not have measures of actual consumption. We also do not have measures of substance use or mental health severity, since we relied on provider assigned clinical diagnoses. The study setting is an integrated health care system, which limits generalizability, but provides an important examination of buprenorphine patients and identifies factors that may impact patients and services in other health systems. Information on prior non-KPNC insurance coverage was unavailable since this study relied on EHR data within the health system. The 6-month follow-up for health service utilization allowed us to measure initial patterns, but analyses of longer time frames will be important to study as health care reform evolves.

Conclusion

In these uncertain times for the ACA’s future, there is considerable concern about the implications of health care reform for vulnerable patients with OUDs. Overall, the experience of buprenorphine patients did not appear to change significantly in the KPNC health care system post ACA. Health systems will likely face increasing number of patients with co-occurring opioid use and marijuana use disorders, and access to services may be challenging, particularly for those with deductible plans. There is surprisingly little research on patterns of mental health services utilization among OUD patients, and given the high comorbidity in this population, this is an important area of research. As health care policy evolves, it will be critical to continue to study patients with OUDs and to examine how their addiction treatment and other encounters within health care systems change over time.

References

- Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Baumeister SE. Changing the U.S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management. San Francisco: Wiley and Sons; 2014. Improving Access to Care. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews CM, D'Aunno TA, Pollack HA, Friedmann PD. Adoption of evidence-based clinical innovations: the case of buprenorphine use by opioid treatment programs. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(1):43–60. doi: 10.1177/1077558713503188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahorik AL, Satre DD, Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Campbell CI. Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated healthcare system. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000260. [published online September 8, 2016. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeuwkes Buntin M, Haviland AM, McDevitt R, Sood N. Healthcare Spending and Preventive Care in High-Deductible and Consumer-Directed Health Plans. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(3):222–30. doi: 48136 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC, Avorn J. Long-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients. JAMA. 2002;288(4):455–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehnke KF, Litinas E, Clauw DJ. Medical Cannabis Use Is Associated With Decreased Opiate Medication Use in a Retrospective Cross-Sectional Survey of Patients With Chronic Pain. J Pain. 2016;17(6):739–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano PA, Lam JM, Morgan SG. Toward a standard definition and measurement of persistence with drug therapy: Examples from research on statin and antihypertensive utilization. Clin Ther. 2006;28(9):1411–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.09.021. discussion 1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Managed Health Care. Mental health care. 2016 http://www.dmhc.ca.gov/HealthCareinCalifornia/GettheBestCare/MentalHealthCare.aspx#paritylaw.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & National Center for Health Statistics. Number and age-adjusted rates of drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics and heroin: United States, 2000–2014. 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/AADR_drug_poisoning_involving_OA_Heroin_US_2000-2014.pdf.

- Chokshi DA, Chang JE, Wilson RM. Health Reform and the Changing Safety Net in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1790–1796. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1608578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covered California. Coverage Levels/Metal Tiers. [Accessed January 3, 2017];2016 http://www.coveredca.com/individuals-and-families/getting-covered/coverage-basics/coverage-levels/

- Frank JW, Binswanger IA, Calcaterra SL, Brenner LA, Levy C. Non-medical use of prescription pain medications and increased emergency department utilization: Results of a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;157:150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith AA, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Rosenthal MB, Gay C, Lieu TA. Delayed and Forgone Care for Families With Chronic Conditions in High-Deductible Health Plans. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1105–11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1970-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon NP. How Does the Adult Kaiser Permanente Membership in Northern California Compare with the Larger Community? 2006 http://www.dor.kaiser.org/external/uploadedFiles/content/research/mhs/_2011_Revised_Site/Documents_Special_Reports/comparison_kaiser_vs_nonKaiser_adults_kpnc%281%29.pdf.

- Han B, Hedden SL, Lipari R, Copello EAP, Kroutil LA. NSDUH data review: receipt of services for behavioral health problems: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Sep, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson E, Catlin M, Andrilla CH, Baldwin LM, Rosenblatt RA. Barriers to primary care physicians prescribing buprenorphine. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):128–33. doi: 10.1370/afm.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and State Treatment Need and Capacity for Opioid Agonist Medication-Assisted Treatment. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e55–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358–67. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur AD, McQueen A, Jan S. Opioid drug utilization and cost outcomes associated with the use of buprenorphine-naloxone in patients with a history of prescription opioid use. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(2):186–94. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Wood E, Grafstein E, Ishida T, Shannon K, Lai C, Montaner J, Tyndall MW. High rates of primary care and emergency department use among injection drug users in Vancouver. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27(1):62–6. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction treatment programs. J Addict Med. 2011;5(1):21–7. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d41ddb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo-Ciganic WH, Gellad WF, Gordon AJ, Cochran G, Zemaitis MA, Cathers T, Kelley D, Donohue JM. Association between trajectories of buprenorphine treatment and emergency department and in-patient utilization. Addiction. 2016;111(5):892–902. doi: 10.1111/add.13270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias Konstantopoulos WL, Dreifuss JA, McDermott KA, Parry BA, Howell ML, Mandler RN, Fitzmaurice GM, Bogenschutz MP, Weiss RD. Identifying patients with problematic drug use in the emergency department: results of a multisite study. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2014;64(5):516–25. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Wier LM, Malone K, Penne M, Cowell AJ. National estimates of behavioral health conditions and their treatment among adults newly insured under the ACA. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(4):426–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, Blanco C, Zhu H, Storr CL. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261–72. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Woodworth AM. The Affordable Care Act and treatment for "substance use disorders:" implications of ending segregated behavioral healthcare. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46(5):541–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens JR, Flisher AJ, Satre DD, Weisner CM. The role of medical conditions and primary care services in 5-year substance use outcomes among chemical dependency treatment patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98(1–2):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens JR, Lu YW, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Weisner CM. Medical and psychiatric conditions of alcohol and drug treatment patients in an HMO: comparison with matched controls. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(20):2511–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. What Buprenorphine is and Why It's Important. NIDA Archives. 2016 https://archives.drugabuse.gov/drugpages/buprenorphine.html.

- Nielsen S, Larance B, Degenhardt L, Gowing L, Kehler C, Lintzeris N. Opioid agonist treatment for pharmaceutical opioid dependent people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD011117. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011117.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell D, Pacula RL. Do medical marijuana laws reduce addictions and deaths related to pain killers? Santa Monica, CA: RAND; Nov, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray GT, Collin F, Lieu T, Fireman B, Colby CJ, Quesenberry CP, Van den Eeden SK, Selby JV. The cost of health conditions in a health maintenance organization. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57(1):92–109. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichard J. Survey shows drop in California's uninsured, but with new cost concerns. The Commonwealth Fund. 2014 Aug 4; http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletters/washington-health-policy-in-review/2014/aug/aug-4-2014/survey-shows-drop-in-californias-uninsured.

- Roman PM, Abraham AJ, Knudsen HK. Using medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders: evidence of barriers and facilitators of implementation. Addict Behav. 2011;36(6):584–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Altschuler A, Parthasarathy S, Silverberg MJ, Volberding P, Campbell CI. Implementation and operational research: Affordable Care Act implementation in a California health care system leads to growth in HIV-positive patient enrollment and changes in patient characteristics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):e76–e82. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Mertens JR, Arean PA, Weisner C. Five-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes of older adults versus middle-aged and younger adults in a managed care program. Addiction. 2004;99(10):1286–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz R, Zelenev A, Bruce RD, Altice FL. Retention on buprenorphine treatment reduces emergency department utilization, but not hospitalization, among treatment-seeking patients with opioid dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43(4):451–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Buprenorphine. [Accessed January 3, 2017];2016 Last Modified May 31, 2016. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment/buprenorphine.

- Tkacz J, Volpicelli J, Un H, Ruetsch C. Relationship between buprenorphine adherence and health service utilization and costs among opioid dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46(4):456–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congress. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001. 2010 https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/html/PLAW-111publ148.htm.

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. ASPE Issue Brief. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. Health insurance coverage and the affordable care act, 2010–2016. [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies--tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters TM, Chang CF, Cecil WT, Kasteridis P, Mirvis D. Impact of High-Deductible Health Plans on Health Care Utilization and Costs. Health Services Research. 2011;46(1 Pt 1):155–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Farmer CM, De Vries D, Hepner KA. The Affordable Care Act: an opportunity for improving care for substance use disorders? Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(3):310–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, Gardin J, Griffin ML, Gourevitch MN, Haller DL, Hasson AL, Huang Z, Jacobs P, Kosinski AS, Lindblad R, McCance-Katz EF, Provost SE, Selzer J, Somoza EC, Sonne SC, Ling W. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(12):1238–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Keeler E, Manning WG., Jr Patterns of outpatient mental health care over time: some implications for estimates of demand and for benefit design. Health Serv Res. 1990;24(6):773–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharam JF, Landon BE, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. High-Deductible Insurance: Two-Year Emergency Department and Hospital Use. American Journal of Managed Care. 2011;17(10):e410–8. doi: 52452 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarborough BJ, Stumbo SP, McCarty D, Mertens J, Weisner C, Green CA. Methadone, buprenorphine and preferences for opioid agonist treatment: A qualitative analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeber JE, Manias E, Williams AF, Hutchins D, Udezi WA, Roberts CS, Peterson AM. A systematic literature review of psychosocial and behavioral factors associated with initial medication adherence: a report of the ISPOR medication adherence & persistence special interest group. Value Health. 2013;16(5):891–900. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]