Abstract

Off‐target adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are associated with significant morbidity and costs to the healthcare system, and their occurrence is not predictable based on the known pharmacological action of the drug's therapeutic effect. Off‐target ADRs may or may not be associated with immunological memory, although they can manifest with a variety of shared clinical features, including maculopapular exanthema, severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs), angioedema, pruritus and bronchospasm. Discovery of specific genes associated with a particular ADR phenotype is a foundational component of clinical translation into screening programmes for their prevention. In this review, genetic associations of off‐target drug‐induced ADRs that have a clinical phenotype suggestive of an immunologically mediated process and their mechanisms are highlighted. A significant proportion of these reactions lack immunological memory and current data are informative for these ADRs with regard to disease pathophysiology, therapeutic targets and biomarkers which may identify patients at greatest risk. Although many serious delayed immune‐mediated (IM)‐ADRs show strong human leukocyte antigen associations, only a small subset have successfully been implemented in screening programmes. More recently, other factors, such as drug metabolism, have been shown to contribute to the risk of the IM‐ADR. In the future, pharmacogenomic targets and an understanding of how they interact with drugs to cause ADRs will be applied to drug design and preclinical testing, and this will allow selection of optimal therapy to improve patient safety.

Keywords: abacavir, adverse drug reaction, aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease, carbamazepine, human leukocyte antigen, pharmacogenomics

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes 2 | GPCRs 3 | Other protein targets 4 |

| COX‐1 | B2 Bradykinin receptor | CTLA‐4 |

| COX‐2 | CCR3 | PD‐1 |

| CYP2B6 | CysLT1 receptor | Transporters 5 |

| CYP2C9 | DP1 receptor | OATP1B1 |

| CYP3A4 | EP1 receptor | Catalytic receptors 6 |

| CYP5A1 | EP2 receptor | Interleukin‐4 receptor subunit α |

| HMG‐CoA reductase | EP3 receptor | |

| 5‐LOX | EP4 receptor | |

| 15‐LOX‐1 | MRGPRX2 | |

| LTC4S | TP receptor | |

| Neutral endopeptidase | ||

| PKCθ | ||

| XPNPEP2 | ||

| X‐prolyl aminopeptidase 1 | ||

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article that are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 1, and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Introduction

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) have been reported to affect 10–20% of hospitalized patients and up to 25% of outpatients, and are a major burden on the healthcare system globally 7, 8, 9. An ADR has been defined as an unintended response to a drug that occurs at standard doses used in the treatment or prevention of a specific disease 10. There is a need to understand both patient‐ and drug‐related risk factors and mechanisms that contribute to these diverse reactions.

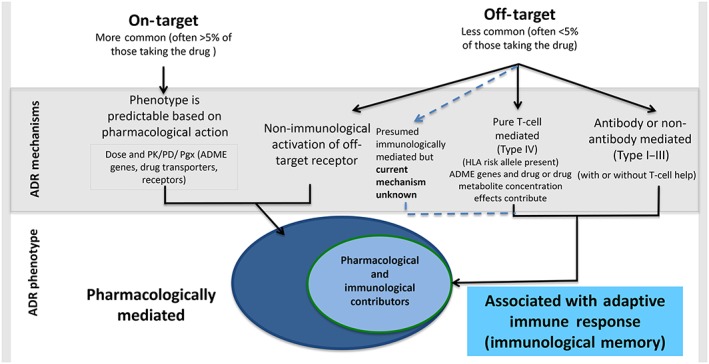

In 1977, Rawlins and Thompson 11 classified ADRs into two major types: type A and type B. Type A reactions are common (>1% of patients taking the drug) and have predictable pharmacological side effects that are consistently dose dependent. Type B reactions are generally uncommon (<1% of patients taking the drug) and are unpredictable based on the known pharmacological action of the drug. These reactions may be directly immunologically mediated in a dose‐independent or ‐dependent manner, related to an off‐target interaction with a pharmacological receptor or to an as‐of‐yet unknown mechanism 11. Much has been discovered about mechanisms of ADRs over the last 15 years – in particular, the fact that host (e.g. pharmacogenomic) and ecological factors are both closely related and contribute to ADR risk. Therefore, we can now construct a classification that differentiates ADRs based on whether they are related to primary on‐target pharmacological effects or by off‐target effects at distant receptors. Indeed, both type A (a type of ‘on‐target’ reaction) and type B (‘off‐target’) reactions may depend on dose and genetic factors, and new discoveries have now elucidated that ‘on‐target’ and ‘off‐target’ reactions alike may be predictable based on host (pharmacogenomics) and ecological risk factors (Figure 1) 12, 13.

Figure 1.

Classification of adverse drug reactions. Adverse drug reactions can be classified according to their on‐target vs. off‐target interactions between the drug and cellular components. Contrary to previous belief, both on‐target and off‐target effects can demonstrate concentration–exposure relationships that may differ between individuals based on acquired or genetic host factors. The interaction between the drug and the target may relate to both the dose and/or duration of treatment. The classical description of on‐target reactions is an augmentation of the known primary therapeutic and pharmacological action of a drug (e.g. bleeding related to warfarin), and off‐target effects can occur by mechanisms that are both directly immune mediated and associated with immunological memory of varied duration (drug allergy), and mechanisms without a direct immunological effect and without immunological memory that may have an ‘immunological phenotype’. These latter reactions are often mediated through a pharmacological interaction (e.g. aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease or the non‐IgE‐mediated mast‐cell activation seen with fluoroquinolones and opioids). Off‐target reactions that result from a primary pharmacological interaction are often dose dependent, whereas immunologically mediated off‐target reactions associated with immunological memory can be both dose dependent (T‐cell‐mediated reactions) or dose independent (recognition and amplification of small amounts of antigen in the case of IgE‐mediated reactions). Predisposition to both on‐target and off‐target reactions is driven not only by genetic variation, but also by ecological factors that can vary over the course of an individual's lifetime (adapted from Phillips 13 and White et al. 86). ADR, adverse drug reaction; ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; pharmacodynamics; pharmacogenomics; PK, pharmacokinetics

Immune‐mediated (IM) ADRs are considered as off‐target reactions and comprise <20% of all ADRs. These reactions were further classified by Gell and Coombs 14, including Type I–III reactions, which are antibody dependent (with or without T cell help), and Type IV reactions, which are delayed, purely T cell‐mediated reactions. Type I reactions are immediate, IgE‐mediated reactions, usually occurring within 1 h after drug administration, and mainly cause urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm, pruritus and anaphylaxis 15. Penicillin allergy is an example of a type I ADR commonly seen in clinical practice. Type IV reactions are mediated by drug‐reactive T lymphocytes and include clinical phenotypes that range from maculopapular exanthema to severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Single‐organ involvement pathologies, such as drug‐induced liver disease (DILI), drug‐induced pancreatitis and drug‐induced agranulocytosis, also comprise immunologically mediated reactions, as evidenced by strong human leukocyte antigen (HLA) associations. Of note, however, and particularly relevant to DILI, toxic mechanisms may also play a significant role 16. Statins cause a dose‐dependent inflammatory myopathy that is more common in the statins metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and patients on inhibitors of CYP3A4. Statin treatment reduces ubiquinone in skeletal muscle and decreases mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, which may be part of the pathogenesis. The organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1) that is encoded by the solute carrier transporter 1B1 (SLCO1B1) gene is involved in the hepatic uptake of most statins. A common variant in this SLCO1B1 gene increases the risk of simvastatin myopathy. Rarely, an autoimmune myopathy can occur with statins, evidenced by autoantibodies against 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG‐CoA) reductase and myocyte necrosis on biopsy 17. HLA‐DRB1*11:01 is associated with statin autoimmune myopathy and is also associated with the development of HMG‐CoA reductase antibodies, even in those without clinical disease 17. Abacavir (ABC) hypersensitivity syndrome and carbamazepine (CBZ)‐induced SJS/TEN are the best characterized CD8+ T‐cell‐mediated ADRs and have significant HLA associations (Table 1) 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32. In addition to these IM‐ADRs that utilize the adaptive immune system and vary with regard to the longevity of immunological memory, there is a separate entity of off‐target reactions that are termed ‘pseudo‐allergic’ as they share some clinical features with type I‐mediated allergy, causing urticaria or pruritus, for example, via mechanisms of non‐IgE‐mediated mast cell activation. In the present review, we discuss what is known about the pharmacogenomics of different types of off‐target drug reactions and opportunities for the translation of pharmacogenomics markers into clinical practice.

Table 1.

Pharmacogenomics of off‐target drug reactions (A) associated with immunological memory and (B) without immunological memory

| A | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | DHR | Alleles | PPV | NPV | NNT | Populations | Level of evidence |

| Abacavir | HSS/DIHS | B*57:01 18, 19, 20, 21 | 55% | 100% | 13 | European, African | 1a |

| Carbamazepine | SJS/TEN | B*15:02 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | 3% | 100% in Han Chinese | 1000 | Han Chinese, Thai, Malaysian, Indian | 1a |

| B*15:11 64, 117 | Korean, Japanese | 3 | |||||

| B*15:18, B*59:01 and C*07:04 76 | Japanese | 3 | |||||

| A*31:01 61, 62, 63, 64 | Japanese, northern European, Korean | 2b | |||||

| HSS/DIHS/DRESS | 8.1 AH (HLA A*01:01, Cw*07:01, B*08:01, DRB1*03:01, DQA1*05:01, DQB1*02:01) 118 | Caucasians | 3 | ||||

| A*31:01 60 | 0.89% | 99.98% | 3334 | Europeans | 1a | ||

| A*31:01 60 | 0.59% | 99.97% | 5000 | Chinese | 1a | ||

| A*31:01 61, 62, 63, 64 | Northern Europeans, Japanese, and Korean | 1a | |||||

| A*11 and B*51 (weak) 63 | Japanese | 3 | |||||

| MPE | A*31:01 23 | 34.9% | 96.7% | 91 | 1a | ||

| Allopurinol | SJS/TEN, DIHS/DRESS | B*58:01 (or B*58 haplotype) 65, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72 | 3% | 100% in Han Chinese | 250 | Han Chinese, Thai, European, Italian, Korean | 1a |

| Oxcarbazepine | SJS/TEN | B*15:02 and B*15:18 74, 119 | Han Chinese, Taiwanese | 2b | |||

| Lamotrigine | SJS/TEN | B*15:02 (positive) 74 | Han Chinese | 3 | |||

| B*15:02 (no association) 120, 121 | Han Chinese | 3 | |||||

| Phenytoin | SJS/TEN |

B*15:02(weak), Cw*08:01 and DRB1*16:02 25, 26, 73, 74

CYP2C9*3 73 |

Han Chinese | 3 | |||

| DRESS/MPE | B*13:01(weak), B*5101 (weak) 73 CYP2C9*3 73 | Han Chinese |

3 3 1a |

||||

| Nevirapine | SJS/TEN | C*04:01 114 | Malawian | 3 | |||

| HSS/DIHS/DRESS |

DRB1*01:01 and DRB1*01:02 (hepatitis and low CD4+) 77, 115 |

18% | 96% | Australian, European and South African |

1b 1b 2b |

||

| Cw*8 or Cw*8‐B*14 haplotype 78, 79 | Italian and Japanese | 2b | |||||

| Cw*4 115, 122 |

Blacks, Asians, Whites Han Chinese |

1b | |||||

|

B*35 115

,

B*35:01 123 , B*35:05 80 |

16% | 97% | Asian |

1b 1b |

|||

| Delayed rash | DRB1*01 124 | French | 2b | ||||

| Cw*04 115, 125 | African, Asian, European, and Thai | 3 | |||||

| B*35:05, rs1576*G CCHCR1 status 80, 126 | Thai | 2b | |||||

| Dapsone | HSS | B*13:01 116 | 7.8% | 99.8% | 84 | 1b | |

| Efavirenz | Delayed rash | DRB1*01 124 | French | 3 | |||

| Sulfamethoxazole | SJS/TEN | B*38 67 | European | ||||

| Amoxicillin–clavulanate | DILI |

DRB1*15:01 A*02:01 DQB1*06:02, and rs3135388, a tag SNP of DRB1*15:01‐DQB1*06:02 DRB1*07 and A1 (protective) 127, 128, 129 |

European |

1b 1b 1b 1b 3 |

|||

| Lumiracoxib | DILI | DRB1*15:01‐DQB1*06:02‐DRB5*01:01‐DQA1*01:02 haplotype 130 | International, multicentre | 2b | |||

| Ximelagatran | DILI | DRB1*07 and DQA1*02 131 | Swedish | 2b | |||

| Diclofenac | DILI | B11, C‐24 T, UGT2B7*2, IL‐4 C‐590‐A 132, 133, 134 | European | 3 | |||

| Flucloxacillin | DILI |

B*57:01 DRB1*07:01‐DQB1*03:01 134, 135 |

0.12% | 99.99% | 13 819 | European | 1b |

| Lapatinib | DILI | DRB1*07:01‐DQA2*02:01‐DQB1*02:02/02:02 136 | International, multicentre | 1b | |||

|

Methimazole/

Carbimazole Antithyroid drugs |

Agranulocytosis |

B*38:02 137, 138

B*27:05 139 (3 snps) |

7% 30% |

99.9% >99% |

211 238 |

Southeast Asian European |

1b 1b |

| Clozapine | Agranulocytosis/neutropenia |

B*59:01 140

DQB1 (126Q) DQB1*05:02; B (158 T) (HLA‐B*39:01, HLA‐B*39:06, B*38:01) 141 Rs149104283 (intronic SLCO1B3 and SLCO1B7) and DQB1 142 |

35.1% |

Japanese European European |

3 3 3 |

||

| Azathioprine | Pancreatitis |

DQA1*02:01; DRB1*07:01 143

Rs2647087* 143 |

9% 17%* |

76 |

European | 3 | |

| Statins | Myopathy | DRB1*11:01 17 | European, African | 2b | |||

| Asparaginase | Anaphylaxis | DRB1*07:01 144 | European | 2b | |||

| Penicillin * |

IgE‐mediated allergy. urticaria IgE‐mediated allergy |

IL‐4Ralpha Q576R 56

IL‐4Ralpha I75V 56 STAT6 in 2SNP3 57 |

Chinese | 3 | |||

| B | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | DHR | Genes | PPV | NPV | NNT | Populations | Level of evidence |

| ACE inhibitors | BSPMA |

B2BKR 51

MME 52 XPNPEP2 53 PKCθ 52 ETV6 52 |

African/African American African American White Canadian White/African American White/African American |

3 2b 3 2b 2b |

|||

| NSAIDS | LHMA |

TSLP 145

ALOX5 40, 146 ALOX15 49 PTGDR 49 PTGER1 40 CYSLTR1 49 |

European European, Korean European European European European |

3 2b 2b 2b 3 2b |

|||

| NSAIDS | AERD/NERD |

ALOX5 146

CYSLTR1 147 TBXA2R 148 PTGER2 148, 149 PTGER3 148 PTGER4 148 CCR3 150 LTC4S 151 COX2 152 DPB1*0301 153 |

Korean Korean Korean Korean, Japanese Korean Korean Korean Japanese Polish Polish, Korean |

3 2b 3 2b 3 3 3 3 3 2b |

|||

LOE [PharmGKB (154, 155, 156, 157)]: Level 1a = annotation for a variant–drug combination in a Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) or medical society‐endorsed pharmacogenomics guideline, or implemented at a Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) site, or in another major health system; Level 1b = annotation for a variant–drug combination in which the preponderance of evidence shows an association. This association must be replicated in more than one cohort with significant P‐values and preferably with a strong effect size; Level 2a = annotation for a variant–drug combination that qualifies for level 2b, in which the variant is within a very important pharmacogene (VIP), as defined by PharmGKB, where their functional significance is more likely known; Level 2b = annotation for a variant–drug combination with moderate evidence of an association. This association must be replicated but there may be some studies that do not show statistical significance, and/or the effect size may be small; Level 3 = annotation for a variant–drug combination based on a single significant (not yet replicated) study or annotation for a variant–drug combination evaluated in multiple studies but lacking clear evidence of an association; Level 4 = annotation based on a case report, nonsignificant study, in vitro, molecular or functional assay evidence only. ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; AERD, aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease; ALOX5, arachidonate 5‐lipoxygenase; ALOX15, arachidonate 15‐lipoxygenase; B2BKR, B2 bradykinin receptor; BSPMA, bradykinin/substance P‐mediated angioedema; CCHCR1, coiled‐coil alpha‐helical rod protein 1; CCR3, c‐c chemokine receptor type 3; COX, cyclo‐oxygenase; CYP, cytochrome P450; CYSLTR1, cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1; DHR, drug hypersensitivity reaction; DIHS, drug‐induced hypersensitivity syndrome; DILI, drug‐induced liver disease; DPB, human leukocyte antigen DPB; DRB, human leukocyte antigen DRB; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; DQB, human leukocyte antigen DQB; EM, extensive metabolizer; ETV6, ETS variant 6; FA, fast acetylator; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HSS, hypersensitivity syndrome; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LHMA, leukotriene/histamine‐mediated angioedema; LOE, levels of evidence; LTC4S, leukotriene C4 synthase; MME, membrane metalloendopeptidase; MPE, maculopapular exanthema; NA, not applicable; NERD, NSAID‐ exacerbated respiratory disease; NNT, number needed to treat; NPV, negative predictive value; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; PPV, positive predictive value; PKCθ, protein kinase C theta; PTGDR, prostaglandin D2 receptor; PTGER, prostaglandin E receptor; SA, slow acetylator; SJS/TEN, Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis; SM, slow metabolizer; TBXA2R, thromboxane A2 receptor; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin; UM, ultrarapid metabolizer; XPNPEP2, x‐linked X‐prolyl aminopeptidase 2

Reactions lacking immunological memory

Reactions with an off‐target pharmacological and/or immunological component

Reactions with an off‐target pharmacological or immunological component may present clinically as urticaria, angioedema and respiratory symptoms classically associated with adaptive immune responses. However, these reactions are not mediated through a primary adaptive immunological mechanism, are not associated with a long‐lasting immunological memory and lack the classical clinical features linked to ADRs associated with immunological memory. In many instances, the primary interaction is between the drug and a pharmacological receptor.

Non‐IgE‐mediated mast cell activation

IgE‐independent activation of mast cells occurs most notably from drugs such as vancomycin, opioids, fluoroquinolones and neuromuscular blocking agents, and may result in anaphylaxis‐like reactions without evidence of IgE cross‐linking. They also occur without evidence of prior drug sensitization, which is necessary for IgE antibody‐dependent reactions 13. Mechanisms involved in non‐IgE‐mediated mast cell degranulation ADRs historically are poorly understood but several new discoveries have occurred, including the human G‐protein coupled receptor (GPCR) gene encoding mas‐related GPR family member X2 (MrgprX2) 33, 34. MrgprX2 is uniquely expressed by connective tissue mast cells. The binding of a specific shared chemical motif, tetrahydroisoquinolone (THIQ), which is on ligands known collectively as basic secretagogues (including inflammatory peptides such as substance P, 48/40, fluoroquinolones, neuromuscular blocking agents, opioids), to MrgprX2 induces mast cell degranulation in a concentration‐dependent manner. Prevention of reactions can occur with dose reduction. This discovery may serve a role in the future prediction of side effects associated with systemic pseudo‐allergic reactions, and identifies MrgprX2 as a potential therapeutic target. Some drugs that cause non‐IgE‐mediated mast cell activation (e.g. vancomycin; personal communication, Dong, unpublished) are not known to interact with the MrgprX2, and the specific mechanism through which vancomycin and some other drugs cause this reaction is currently unknown.

Aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD)

AERD is characterized by asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis that is worsened by exposure to nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin and other nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors 35. The prevalence among asthmatics is much higher in adults than in children (21 vs. 5% by oral provocation testing). In one study, AERD was estimated to be present in 4.3–11% of adult asthmatics 36, but in 34% of asthmatics who also have nasal polyposis and chronic rhinosinusitis 37. In a study of 300 patients in the USA, the female‐to‐male ratio was found to be 3:2 38. There is no predilection for AERD based on race, ethnicity or family history 38. COX‐1 is the enzyme responsible for the production of prostaglandins (PGs) from arachidonic acid. PGE2 binds to receptors in the lung, causing smooth muscle relaxation and a decrease in the release of leukotrienes from mast cells; this causes bronchoconstriction and inflammatory cell recruitment. NSAID‐mediated inhibition of COX‐1 prevents the production of PGE2, which ultimately causes a shift in the response to increased production of leukotrienes, and increased symptoms common in AERD. Genetic predictors of these reactions to aspirin, and NSAIDs more broadly, have been examined and belong to the arachidonic acid pathway [the genes encoding arachidonate 5‐lipoxygenase (ALOX5), leukotriene C4 synthase (LTC4Si), the thromboxane A2 receptor (TBXA2R), prostaglandin E receptor 4 (PTGER4)], the membrane‐spanning 4A gene family, the histamine production pathway and the proinflammatory cytokines [tumour necrosis factor (TNF), transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1), interleukin 18 (IL‐18)] 39, 40. In addition, recent genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) have identified the genes encoding centrosomal protein 68 (CEP68) and HLA‐DPB1 as the strongest candidates associated with AERD 41, 42.

NSAID‐induced or ‐exacerbated urticaria/angioedema

Separate from AERD, aspirin and other NSAID drugs are known to cause cutaneous hypersensitivities, including NSAID‐exacerbated urticaria/angioedema (as a form of chronic urticaria) and isolated or cross‐reactive NSAID‐induced urticaria/angioedema 43. HLA genes (HLA‐DRB1*11, HLA‐B44, HLA‐Cw5) and arachidonic acid pathway genes [ALOX5, and the genes encoding ALOX5‐activating protein (ALOX5AP), arachidonate 15‐lipoxygenase (ALOX15), thromboxane A synthase 1 (TBXAS1), prostaglandin D2 receptor (PTGDR), and cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (CYSLTR1)] have been identified as predictors of these immune‐mediated dermatological NSAID drug reactions 40, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48. A current theoretical understanding suggests that patients with these underlying variants are predisposed to an imbalance of proinflammatory vs. anti‐inflammatory arachidonic acid metabolite activity, and are therefore more susceptible to COX‐1 inhibition of PGE2 and/or increases in leukotrienes, similar to the model for AERD 49, 50. It remains to be understood what leads to the differences in presentation between the two diseases, given the significant overlap in genes that are associated with both phenotypes.

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi)‐associated angioedema

Genetic variants associated with ACEi angioedema are typically involved in the activity of or breakdown pathways for bradykinin and substance P. Variants in the bradykinin receptor 2 and neprilysin genes have been implicated as important in patients of African descent 51, 52. Similarly, variants in the x‐linked X‐prolyl aminopeptidase 2 (XPNPEP2) gene encoding the cytosolic form of aminopeptidase P, a metalloproteinase that degrades bradykinin, has been associated with ACEi angioedema in French Canadians 53 and in both white and black men, but not women, from Tennessee 54. Variants in the protein kinase C theta (PKCθ) and ETS variant 6 (ETV6) genes have been simultaneously associated with ACEi‐induced angioedema in the genetically heterogeneous populations of Nashville, TN, and Marshfield, WI 52. None of these associations reached genome‐wide significance.

Reactions involving immunological memory

Immediate/accelerated IM reactions

Immediate reactions (<1 h after drug administration) and early accelerated reactions (< 6 h after drug administration) may utilize IgE‐dependent pathways, while accelerated reactions that occur between 6–72 h after administration of drug are more likely to be T‐cell mediated or non‐IgE mediated. Most genetic studies have focused on immediate drug hypersensitivity to beta‐lactams, aspirin or NSAIDs. A small number of GWAS have examined antibiotic‐associated ADRs but any single implicated gene has remained elusive to date. However, for immediate reactions to beta‐lactams, the greatest association appears in the HLA class II antigen‐presenting genes, cytokines (IL4, IL13, IL18, IL10) and the cytokine receptor (IL4R), and the production and release of preformed mediators [the galectin‐3 gene (LGALS3) being the strongest predictor] 44, 55, 56, 57, 58. There have been limited genomic studies examining IM immediate hypersensitivity outside of antibiotics and anti‐inflammatory agents.

Delayed immune reactions

Delayed IM‐ADRs are driven by the inappropriate activation of T cells. The key proteins that mediate these immune responses are thought to be primarily HLA molecules encoded within the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on chromosome 6. The MHC genes are the most polymorphic, with >5000 allelic variants, >2500 on HLA‐B alone. The T‐cell receptor (TCR) on the surface of a T cell recognizes peptides that are bound and displayed by surface HLA molecules that are expressed on various cells of the immune system. Class I MHC molecules (HLA‐A, ‐B and ‐C) are expressed on all nucleated cells and are responsible for activating CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, while class II MHC molecules (HLA‐DP, HLA‐DQ and HLA‐DR) are expressed only on professional antigen‐presenting cells (B cells, macrophages and dendritic cells) and activate CD4+ helper T lymphocytes 59. The sequences within the peptide binding groove are the most polymorphic, such that each HLA allotype presents a unique repertoire of peptides to a T cell, and inheriting one allele from each parent broadens the probability that a pathogen will be recognized and eliminated. However, the potential for the greatest diversity is reduced by the linkage disequilibrium observed within the HLA class I and class II loci. During the last decade, many strong associations between HLA molecules and the development of certain drug hypersensitivity syndromes, such as DRESS/drug‐induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) and SJS/TEN, have been reported (Table 1) 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73. These associations have led, in some well‐defined cases, to screening programmes in the prevention of drug hypersensitivity reactions 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, 26, 30, 65, 66, 67, 68, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81. In addition to the examples highlighted below, there are many other delayed hypersensitivity reactions that exhibit both class I and II HLA associations. Due to the strong linkage disequilibrium, attempting to disentangle associations with closely linked HLA genes can be difficult. Strong data do exist for ABC hypersensitivity, however, to support that HLA‐B*57:01 is necessary but not sufficient for the development of disease and that markers closely linked but in incomplete linkage disequilibrium with HLA‐B*57:01, such as HCP5 rs2395029, may be negative in cases of patch test‐positive ABC hypersensitivity. As there is no surrogate marker for HLA‐B*57:01 in the case of ABC hypersensitivity, this also provides a cautionary note for the utilization of a simple HCP5 rs2395029 TaqMan assay to screen for ABC hypersensitivity prior to ABC prescription, as such an assay, unlike for HLA‐B*57:01, would have a less than 100% negative predictive value (NPV) for immunologically confirmed ABC hypersensitivity 82. The HLA allele found to be associated with disease susceptibility may not necessarily fully explain the immunopathogenesis of the underlying interaction, and further discovery may include genetic factors outside the MHC. In addition, some severe T‐cell mediated ADRs may conform to a heterologous immunity model, whereby the drug hypersensitivity reaction represents a cross‐reactive memory T‐cell response between the drug and self‐peptide, and a response that occurred much earlier in life to a chronic prevalent virus 78. However, examining these very strong drug–HLA associations sheds light on the general mechanisms that are important in the development of delayed drug hypersensitivity.

The three nonmutually exclusive established models for T‐cell‐mediated hypersensitivity include the hapten/prohapten model, the pharmacological interactions of drugs with immune receptors (p‐i) model and the altered repertoire model. These concepts have been extensively reviewed elsewhere and will be briefly discussed here. The hapten/prohapten model involves the covalent binding of a small neutral drug (hapten) or its reactive metabolite (prohapten), which is not immunogenic alone, to an endogenous protein which is then processed intracellularly and displayed on an MHC molecule as a neoantigen for recognition by a T cell and induction of an immune response 14, 83, 84, 85, 86. This has been best characterized by penicillin derivatives and sulfamethoxazole metabolites 85, 87.

The p‐i concept proposes that a drug can bind directly to either the TCR or MHC molecule, independent of antigen processing, and stimulate T cells directly with sufficient affinity 88. This hypothesis explains how some drugs can cause IM‐ADRs after the first exposure, without prior sensitization, and the in vitro T cell reactivity that has been observed within seconds of drug exposure which is not consistent with intracellular antigen processing 89, 90, 91, 92.

The altered peptide repertoire model is an expansion of the p‐i concept and is best explained with ABC and its association with HLA‐B*57:01. ABC binds noncovalently in a concentration‐dependent manner to the peptide binding groove of HLA‐B*57:01, specifically incorporating in the F pocket, and alters the shape and chemistry in such a way that the HLA molecule binds and displays an altered set of self‐peptides that are then recognized by T cells as foreign 59, 93, 94.

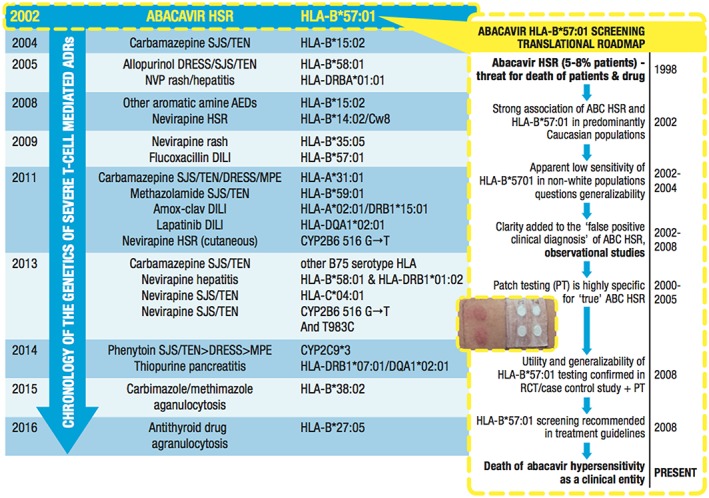

Identifying the true phenotypic drug hypersensitivity entity with specificity has proven to be key to identifying the pharmacogenomics markers associated with these syndromes 95. The ABC example has provided a translational roadmap from the pathway of discovery of a pharmacogenetic association to clinical implementation in routine clinical care and the prevention of drug toxicity (Figure 2) 95. Early doubts about the applicability of HLA‐B*57:01 routine testing were raised, based on an apparent low sensitivity in black and Hispanic populations, where allelic frequency is low 96. The low sensitivity was, in fact, due to a high number of false‐positive diagnoses in these populations and this was highlighted in ABC double‐blind, randomized trials in which up to 7% of patients not receiving ABC were given the clinical diagnosis of ABC HSS or ABC hypersensitivity syndrome 82. To overcome this problem, specificity for ABC was achieved by using the specific skin patch test, which identified those individuals with true IM ABC hypersensitivity, utilized by two distinct clinical trials looking at ABC predictability and prevention 20, 21, 81, 97, 98. HLA‐B*57:01 screening prior to ABC treatment has been widely implemented in routine clinical practice and is part of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and international human immunodeficiency virus treatment guidelines.

Figure 2.

Chronology of the pharmacogenomics of severe immunologically mediated adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The discovery of the very strong association between abacavir (ABC) hypersensitivity and the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B*57:01 gene (HLA‐B*57:01) was the landmark that first linked drug hypersensitivity to class I‐restricted, T cell‐driven mechanisms 18, 19. This discovery set in motion a translational roadmap (right frame) that involved a number of steps that were necessary to confirm the utility, safety and generalizability of HLA‐B*57:01 testing, and resulted in the widespread use of HLA‐B*57:01 testing as a guideline‐based screening test prior to ABC prescription in routine human immunodeficiency virus clinical practice. Since the availability of sequence‐based and deep sequencing methods for high‐resolution typing, there has been a plethora of discoveries over the last 15 years linking severe immune‐modulated ADRs with HLA class I and II alleles. Particularly with severe cutaneous adverse reactions that are CD8+ T cell dependent, such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN), class I‐restricted HLA associations have dominated. Significant insights into the immunopathogenesis of severe T‐cell‐mediated ADRs have been garnered from these class I‐restricted reactions such as the strong association between carbamazepine SJS/TEN and HLA‐B*15:02 in Southeast Asian populations, and allopurinol severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) and HLA‐B*58:01. Some additional distinct examples exist, such as the importance of HLA class I/II haplotypes in the setting of amoxicillin–clavulanate (Amox‐clav) drug‐induced liver disease in Northern Europeans and phenotype‐specific HLA associations for nevirapine hypersensitivity 77, 78, 79, 80, 114, 115, 116. More recently, for phenytoin [the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C9*3 gene (CYP2C9*3) 73 and nevirapine (CYP2B6 516G > T) SCARs 115, impaired drug metabolism appears to be an important driver. AED, anti‐epileptic drug; DILI, drug‐induced liver disease; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; HSR, hypersensitivity reaction; MPE, maculopapular exanthema; NVP, negative predictive value; RCT, randomized controlled trial

Other hypersensitivity reactions with well‐characterized class I HLA associations include CBZ‐induced SJS/TEN with HLA‐B*15:02 and allopurinol SJS/TEN and DRESS with HLA‐B*58:01 (Table 1). These high odds ratio, high‐risk alleles have much lower positive predictive values (PPVs) (<3%) for the specific allele when compared with HLA‐B*57:01 (55%) and the ABC hypersensitivity syndrome.

CBZ is an aromatic amine anticonvulsant reported to cause a spectrum of IM‐ADRs, including maculopapular exanthema, DRESS and SJS/TEN. Initially reported in 2004, CBZ‐induced SJS/TEN is strongly associated with HLA‐B*15:02 in most Asian populations, specifically the Han Chinese, where the allelic frequency is high. In the Han Chinese population, HLA‐B*15:02 was present in 100% of the SJS/TEN patients (also found in 3% of CBZ‐tolerant individuals and in 8.6% of the general population) 22, 24, 31. This association is specific to the CBZ SJS/TEN phenotype and HLA‐B*15:02 has shown no association with nonblistering cutaneous reactions such as DRESS 95. The other aromatic amine anticonvulsants, including oxcarbamazepine, phenytoin and potentially lamotrigine, have been reported to have a weaker association with HLA‐B*15:02, suggesting structural similarities of these aromatic amine anticonvulsants contributing to risk 23, 60, 61, 74. Additional studies have confirmed this association of HLA‐B*15:02 in other populations with Chinese ancestry; however, the same association was not shown in the Japanese and European populations, where the allelic frequencies of HLA‐B*15:02 are <0.1% and <1%, respectively 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 75. HLA‐A*31:01, which is present in approximately 7% of Han Chinese, 7–12% of Japanese, 5% of Koreans and 2–5% of northern European populations [allelefrequencies.net], has shown a much stronger association with DRESS in Taiwanese, Japanese and European populations than SJS/TEN, where the association between HLA‐A*31:01 and CBZ SJS/TEN appears to be limited to European and Japanese populations 23, 61, 62, 63, 75, 86. Subsequent studies of HLA‐B*15:02‐associated CBZ‐induced SJS/TEN has demonstrated a dominant T‐cell receptor clonotype [Hung and Chung, unpublished data]. This raises the hypothesis that, in some cases, the risk of severe IM‐ADRs may be driven by a primary immune response to a prevalent chronic persistent pathogen which later manifests as a cross‐reactive response with the drug‐self‐peptide 86, 99.

Phenytoin has been associated with SCARs, including maculopapular exanthema, DRESS and SJS/TEN. A recent GWAS study across mixed ethnic populations, including Taiwan, Japan and Malaysia, identified a missense variant of the CYP2C9 gene, whose protein product is responsible for metabolizing phenytoin in the liver. The variant, identified as CYP2C9*3, was strongly associated with the development of SCARs (odds ratio 11; 95% confidence interval 6.2, 18; P < 0.0001) 73. The CYP2C9*3 variant was associated with a 93–95% reduction in parent phenytoin clearance. However, delayed clearance was also observed in individuals without this variant allele, suggesting other contributing factors, such as hepatic or renal insufficiency or drug–drug interaction. This study also demonstrated weaker genetic associations with HLA‐B alleles, including HLA‐B*13:01, HLA‐B*15:02 and HLA‐B*51:01, suggesting that a combination of pharmacological and immunological mechanisms contribute to the development of phenytoin‐related SCARs 73, 86.

Previous work in Han Chinese has identified the HLA‐B*58:01 allele as a genetic marker for SJS/TEN/DRESS induced by allopurinol, a commonly prescribed medication for gout (100% NPV and 3% PPV) 65. The incidence of true allopurinol hypersensitivity is rare, with estimates of approximately 0.1%. Subsequent studies demonstrated this association in Thai, Korean and Japanese populations, and it has been estimated that HLA‐B*58:01 is responsible for approximately 60% of allopurinol‐induced ADRs in European and Japanese populations 66, 68, 69, 100, 101. The exact mechanism by which allopurinol causes different drug hypersensitivity phenotypes remains unknown, although it has been proposed that the longer half‐life metabolite of allopurinol, oxypurinol, may be small enough to bind to multiple sites on an HLA molecule and directly activate T cells, as demonstrated in vitro with rapid proliferation within seconds of exposure, suggesting processing‐independent mechanisms 102, 103. It is currently not clear how an ADR restricted to a single HLA allele can manifest in diverse clinical phenotypes for some drugs (e.g. allopurinol and HLA‐B*58:01) but not others (e.g. HLA‐B*15:02 and CBZ SJS/TEN but not DRESS). The low PPV of HLA‐B*58:01 carriage as a predictor for the development of SJS/TEN/DRESS suggests that other contributing factors are at play 102. It is now known that increased serum oxypurinol concentrations contribute to the development of allopurinol‐induced ADRs, and these occur in a concentration‐dependent manner, with increased severity of clinical phenotype 104.

Translation of pharmacogenomic testing into clinical practice

For reactions lacking immunological memory that may have pharmacological and/or immunological mechanisms, the elucidation of pharmacogenomic associations has been important either to support pre‐existing knowledge of mechanisms or to drive further discovery of the pathophysiology of these diseases. Non‐IgE‐mediated mast‐cell activation related to drugs that interact with MrgprX2 is an example where the relationship between risk of disease and polymorphism in this receptor is currently being explored. For other diseases (e.g. AERD and NSAID‐induced urticaria), there may be a greater degree of pharmacogenomic heterogeneity that precludes identification of a single risk or risk factors prior to prescription. Universally, however, the identification of genetic factors associated with these off‐target ADRs has heightened understanding of the specific clinical phenotypes, as well as their pathophysiology, and has been important in the identification of biomarkers and novel therapeutic targets.

Immediate reactions associated with immunological memory, such as anaphylaxis with penicillins and other drugs, represent an additional challenge as most patient labelled as allergic do not have disease. In addition, defined immunological responses (as measured by ex vivo techniques and skin testing) are legitimately lost over time 105, 106. It is more likely for these reactions that specific genetic risk factors will elucidate the immunopathogenesis of these reactions as well as risk‐stratify patients and potentially identify those who are more likely to have experienced true immediate reactions. Genetic screening may not be beneficial as a primary screening strategy, however, due to cost and scale.

The application of genetic screening for IM‐ADRs would have highest utility for those diseases which are prevalent, severe and associated with HLA markers that show a high PPV and 100% NPV, as demonstrated by the ABC example and for which a long‐lasting memory response, and hence a life‐long risk, to a severe IM‐ADR exists. Much of the success of the implementation of HLA‐B*57:01 testing in clinical practice relates to its 100% NPV, relatively high (55%) PPV and the fact that only 13 subjects need to be tested to prevent one case of immunologically confirmed hypersensitivity, making testing extremely cost‐effective. Current evidence suggests that HLA‐B*57:01 is necessary but not sufficient for the development of ABC hypersensitivity. It remains unclear why only 55% of HLA*B‐57:01‐positive individuals experience ABC hypersensitivity, when drug‐specific T‐cells can be identified in vitro in 100% of HLA‐B*57:01‐positive and in no HLA‐B*57:01‐negative individuals, and this may relate to genetic factors outside of the MHC 107. For many dose‐related off‐target ADRs, pharmacogenomic screening and testing alone may not explain the full clinical phenotype. There is also often additional significant interindividual variation in drug exposure that may be explained by ecological factors such as disease state or organ function. Therefore, pharmacogenomic testing does not displace the need to measure drug levels or carry out therapeutic drug monitoring, giving important and independent qualitative and quantitative information to guide clinical management. Most off‐target reactions, including those associated with immunological memory, are dose‐ and concentration dependent. The notable exception is IgE‐mediated reactions, where the immune system is primed to recognize tiny amounts of antigen, which are amplified through IgE to culminate in mast‐cell activation. Most research currently has focused on the pharmacogenetics of drug hypersensitivity syndromes and SJS/TEN/DRESS associated with drugs such as abacavir, nevirapine, anticonvulsants and allopurinol. Further work and collaborations are needed to determine the genetic basis of other drug reactions as well as other non‐genetic contributing factors – for instance, to explain why 45% of individuals with HLA‐B*57:01 would not develop abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome. Regardless of its low PPV (3%), the FDA recommends prescreening individuals of Southeast Asian ancestry before the initiation of CBZ. These examples fail to explain why not all patients with the HLA allele exposed to the drug develop hypersensitivity or why different drug‐HLA allele combinations result in such different clinical syndromes, and contribute to the knowledge that genetic and ecological predictors alike contribute to drug hypersensitivity.

New mechanisms of off‐target drug toxicities and future perspectives

Advances in immuno‐oncology have seen promising new interventions that target the host response against the tumour 108. In particular, monoclonal antibodies that block immune checkpoints on T cells have significantly improved survival in metastatic melanoma, where they are now first‐line therapy, and several further drugs targeting other immune checkpoints are in development. These classes of drugs are currently being studied or used in an off‐label fashion in the treatment of many other solid tumours and haematological malignancies. The anti‐cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA‐4) inhibitor ipilimumab, the anti‐programmed death receptor 1 (PD‐1) inhibitor nivolumab, the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab, and the anti‐PD1 inhibitor pembrolizumab have been approved in the USA and Europe. Checkpoint inhibitors have been associated with a wide array of organ‐specific immune‐related adverse events (irAEs), which most commonly are dermatological (usually mild rash and rarely SJS/TEN), gastrointestinal, hepatitis, endocrine (thyroiditis, pancreatitis), haematological (red cell aplasia), neurological (Guillain‐Barré, aseptic meningitis), myocarditis and rheumatological [systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), polyarthritis] syndromes 109. The most common irAEs occur within 3–6 months of initiation of checkpoint inhibitor therapy and are mild, not treatment limiting and will respond to steroids when necessary 110. An increasing number of severe reactions with high morbidity and mortality are now being described, particularly with the use of combination anti‐CTLA‐4 and anti‐PD‐1 therapy 111. Interestingly, polymorphisms of CTLA‐4 and PD‐1 have been associated with autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune thyroiditis, coeliac disease, SLE and rheumatoid arthritis; however, typically no autoantibodies are identified in the case of checkpoint inhibitor‐associated irAEs 109. Currently, the genetic and ecological risk factors predisposing to checkpoint inhibitor‐associated irAEs have not been identified. Some clues may be that specific toxicities may be more common in certain tumour types (e.g. vitiligo in melanoma). In some cases, the toxicities could represent a cross‐reactive response between tissue antigens and tumour neoantigens. This is supported by superior tumour response outcomes in individuals who develop checkpoint inhibitor toxicities, and also two recent fatal cases of myocarditis where the same expanded T‐cell receptor clonotype and similar spectrum of T‐cell receptor clonotypes were seen in biopsies from the post‐checkpoint inhibitor tumour tissue and the post‐mortem heart biopsies 109, 111. Shared or similar tumour and microbial antigens have been reported, raising the possibility that there could be a cross‐reactive memory T‐cell response between the tumour and microbial antigen in the tissue in question 112, 113. It is currently unknown whether the risk of HLA‐restricted drug reactions could be increased in the presence of drugs targeting immune checkpoints; however, this is an important area of future research.

Conclusions

In the future, with the identification of defined clinical phenotypes, improvements in the technology and tools defining the pharmacogenomics of off‐target ADRs will become readily achievable. It is anticipated that many of these will not have direct translation into clinical practice as a primary screening strategy, but they will be critical in advancing understanding of the mechanisms of these reactions. It is further anticipated that discovery of novel HLA associations for off‐target ADRs associated with immunological memory will remain prevalent and important for the translation of screening strategies into clinical practice. Further research into the immunopathogenesis of ADRs associated with immunological memory is necessary to improve our understanding of the molecular interactions between drugs, HLA molecules and the TCR. This will be critical to advancing our understanding as to why only a small proportion of patients carrying a specific HLA risk allele will develop an IM‐ADR. Ultimately, this progress will guide the development of preclinical screening programmes to enable safer, more efficient and cost‐effective drug design.

Competing Interests

E.J.P. is Co‐Director of IIID Pty Ltd, which holds a patent for HLA‐B*57:01 testing. The authors have no other competing interests or conflicts of interest to declare.

E.J.P. is supported through 1P50GM115305–01 1R01AI103348–01, 1P30AI110527‐01A1, The National Health & Medical Research Association (Australia) and Australian Centre for HIV & Hepatitis Research (ACH2). N.J.B. is supported through R01HL079184 (NIH) and has received research funding from Shire pharmaceuticals . C.A.S. is supported through T32 HL87738 (NIH/NHLBI).

Garon, S. L. , Pavlos, R. K. , White, K. D. , Brown, N. J. , Stone, C. A. Jr , and Phillips, E. J. (2017) Pharmacogenomics of off‐target adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 83: 1896–1911. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13294.

References

- 1. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44 (D1): D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alexander SP, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alexander SP, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 5744–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alexander SP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, Faccenda E, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Overview. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 5729–5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alexander SP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, Faccenda E, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Transporters. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 6110–6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alexander SP, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Catalytic receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 5979–6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borus J, Seger AC, Peterson J, Burdick E, et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1556–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gomes ER, Demoly P. Epidemiology of hypersensitivity drug reactions. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2005; 5: 309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta‐analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 1998; 279: 1200–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roychowdhury S, Svensson CK. Mechanisms of drug‐induced delayed‐type hypersensitivity reactions in the skin. AAPS J 2005; 7: E834–E846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rawlins MD,TJ. Pathogenesis of adverse drug reactions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aronson JK, Ferner RE. The law of mass action and the pharmacological concentration‐effect curve: resolving the paradox of apparently non‐dose‐related adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 81: 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Phillips EJ. Classifying ADRs – does dose matter? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 81: 10–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Demoly P, Adkinson NF, Brockow K, Castells M, Chiriac AM, Greenberger PA, et al. International consensus on drug allergy. Allergy 2014; 69: 420–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Metushi I, Uetrecht J, Phillips E. Mechanism of isoniazid‐induced hepatotoxicity: then and now. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 81: 1030–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mammen AL. Statin‐associated autoimmune myopathy. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 664–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hetherington S, Hughes AR, Mosteller M, Shortino D, Baker KL, Spreen W, et al. Genetic variations in HLA‐B region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir. Lancet 2002; 359: 1121–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mallal S, Nolan D, Witt C, Masel G, Martin AM, Moore C, et al. Association between presence of HLA‐B*5701, HLA‐DR7, and HLA‐DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV‐1 reverse‐transcriptase inhibitor abacavir. Lancet 2002; 359: 727–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, Molina JM, Workman C, Tomazic J, et al. HLA‐B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 568–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saag M, Balu R, Phillips E, Brachman P, Martorell C, Burman W, et al. High sensitivity of human leukocyte antigen‐b*5701 as a marker for immunologically confirmed abacavir hypersensitivity in white and black patients. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46: 1111–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, Hsih MS, Yang LC, Ho HC, et al. Medical genetics: a marker for Stevens‐Johnson syndrome. Nature 2004; 428: 486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hung SI, Chung WH, Jee SH, Chen WC, Chang YT, Lee WR, et al. Genetic susceptibility to carbamazepine‐induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2006; 16: 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kulkantrakorn K, Tassaneeyakul W, Tiamkao S, Jantararoungtong T, Prabmechai N, Vannaprasaht S, et al. HLA‐B*1502 strongly predicts carbamazepine‐induced Stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Thai patients with neuropathic pain. Pain Pract 2012; 12: 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Locharernkul C, Loplumlert J, Limotai C, Korkij W, Desudchit T, Tongkobpetch S, et al. Carbamazepine and phenytoin induced Stevens‐Johnson syndrome is associated with HLA‐B*1502 allele in Thai population. Epilepsia 2008; 49: 2087–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Man CB, Kwan P, Baum L, Yu E, Lau KM, Cheng AS, et al. Association between HLA‐B*1502 allele and antiepileptic drug‐induced cutaneous reactions in Han Chinese. Epilepsia 2007; 48: 1015–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Then SM, Rani ZZ, Raymond AA, Ratnaningrum S, Jamal R. Frequency of the HLA‐B*1502 allele contributing to carbamazepine‐induced hypersensitivity reactions in a cohort of Malaysian epilepsy patients. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2011; 29: 290–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang Q, Zhou JQ, Zhou LM, Chen ZY, Fang ZY, Chen SD, et al. Association between HLA‐B*1502 allele and carbamazepine‐induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions in Han people of southern China mainland. Seizure 2011; 20: 446–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhao LM, Peng W, Shen GQ, Xue L, et al. Strong association between HLA‐B*1502 and carbamazepine‐induced Stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in mainland Han Chinese patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011; 67: 885–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang CC, Too CL, Murad S, Hussein SH. Association of HLA‐B*1502 allele with carbamazepine‐induced toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens‐Johnson syndrome in the multi‐ethnic Malaysian population. Int J Dermatol 2011; 50: 221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tassaneeyakul W, Tiamkao S, Jantararoungtong T, Chen P, Lin SY, Chen WH, et al. Association between HLA‐B*1502 and carbamazepine‐induced severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions in a Thai population. Epilepsia 2010; 51: 926–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu XT, Hu FY, An DM, Yan B, Jiang X, Kwan P, et al. Association between carbamazepine‐induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions and the HLA‐B*1502 allele among patients in central China. Epilepsy Behav 2010; 19: 405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McNeil BD, Pundir P, Meeker S, Han L, Undem BJ, Kulka M, et al. Identification of a mast‐cell‐specific receptor crucial for pseudo‐allergic drug reactions. Nature 2015; 519: 237–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Subramanian H, Gupta K, Ali H. Roles of Mas‐related G protein‐coupled receptor X2 on mast cell‐mediated host defense, pseudoallergic drug reactions, and chronic inflammatory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138: 700–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Farnam K, Chang C, Teuber S, Gershwin ME. Nonallergic drug hypersensitivity reactions. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2012; 159: 327–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sanchez‐Borges M. NSAID hypersensitivity (respiratory, cutaneous, and generalized anaphylactic symptoms). Med Clin North Am 2010; 94: 853–864 xiii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stevenson DD, Szczeklik A. Clinical and pathologic perspectives on aspirin sensitivity and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118: 773–786 quiz 87‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berges‐Gimeno MP, Simon RA, Stevenson DD. The natural history and clinical characteristics of aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2002; 89: 474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Oussalah A, Mayorga C, Blanca M, Barbaud A, Nakonechna A, Cernadas J, et al. Genetic variants associated with drugs‐induced immediate hypersensitivity reactions: a PRISMA‐compliant systematic review. Allergy 2016; 71: 443–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Plaza‐Serón M, Ayuso P, Pérez‐Sánchez N, Doña I, Blanca‐Lopez N, Flores C, et al. Copy number variation in ALOX5 and PTGER1 is associated with NSAIDs‐induced urticaria and/or angioedema. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2016; 26: 280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim JH, Park BL, Cheong HS, Bae JS, Park JS, Jang AS, et al. Genome‐wide and follow‐up studies identify CEP68 gene variants associated with risk of aspirin‐intolerant asthma. PLoS One 2010; 5: e13818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Park BL, Kim TH, Kim JH, Bae JS, Pasaje CF, Cheong HS, et al. Genome‐wide association study of aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease in a Korean population. Hum Genet 2013; 132: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kowalski ML, Woessner K, Sanak M. Approaches to the diagnosis and management of patients with a history of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug‐related urticaria and angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136: 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cornejo‐Garcia JA, Gueant‐Rodriguez RM, Torres MJ, Blanca‐Lopez N, Tramoy D, Romano A, et al. Biological and genetic determinants of atopy are predictors of immediate‐type allergy to betalactams, in Spain. Allergy 2012; 67: 1181–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ayuso P, Plaza‐Seron Mdel C, Dona I, Blanca‐Lopez N, Campo P, Cornejo‐Garcia JA, et al. Association study of genetic variants in PLA2G4A, PLCG1, LAT, SYK, and TNFRS11A genes in NSAIDs‐induced urticaria and/or angioedema patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2015; 25: 618–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pacor ML, Di Lorenzo G, Mansueto P, Martinelli N, Esposito‐Pellitteri M, Pradella P, et al. Relationship between human leucocyte antigen class I and class II and chronic idiopathic urticaria associated with aspirin and/or NSAIDs hypersensitivity. Mediators Inflamm 2006; 2006: 62489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Quiralte J, Sanchez‐Garcia F, Torres MJ, Blanco C, Castillo R, Ortega N, et al. Association of HLA‐DR11 with the anaphylactoid reaction caused by nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103: 685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vidal C, Porras‐Hurtado L, Cruz R, Quiralte J, Cardona V, Colas C, et al. Association of thromboxane A1 synthase (TBXAS1) gene polymorphism with acute urticaria induced by nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132: 989–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cornejo‐García J, Jagemann L, Blanca‐López N, Doña I, Flores C, Guéant‐Rodríguez R, et al. Genetic variants of the arachidonic acid pathway in non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug‐induced acute urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy 2012; 42: 1772–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Parker AR, Ayars AG, Altman MC, Henderson WR Jr. Lipid mediators in aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2016; 36: 749–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moholisa RR, Rayner BR, Patricia Owen E, Schwager SL, Stark JS, Badri M, et al. Association of B2 receptor polymorphisms and ACE activity with ACE inhibitor‐induced angioedema in black and mixed‐race South Africans. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2013; 15: 413–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pare G, Kubo M, Byrd JB, McCarty CA, Woodard‐Grice A, Teo KK, et al. Genetic variants associated with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor‐associated angioedema. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2013; 23: 470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Duan QL, Nikpoor B, Dube MP, Molinaro G, Meijer IA, Dion P, et al. A variant in XPNPEP2 is associated with angioedema induced by angiotensin I‐converting enzyme inhibitors. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 77: 617–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Woodard‐Grice AV, Lucisano AC, Byrd JB, Stone ER, Simmons WH, Brown NJ. Sex‐dependent and race‐dependent association of XPNPEP2 C‐2399A polymorphism with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor‐associated angioedema. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2010; 20: 532–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gueant JL, Romano A, Cornejo‐Garcia JA, Oussalah A, Chery C, Blanca‐Lopez N, et al. HLA‐DRA variants predict penicillin allergy in genome‐wide fine‐mapping genotyping. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Huang CZ, Yang J, Qiao HL, Jia LJ. Polymorphisms and haplotype analysis of IL‐4Ralpha Q576R and I75V in patients with penicillin allergy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 65: 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Huang CZ, Zou D, Yang J, Qiao HL. Polymorphisms of STAT6 and specific serum IgE levels in patients with penicillin allergy. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012; 50: 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ming L, Wen Q, Qiao HL, Dong ZM. Interleukin‐18 and IL18 ‐607A/C and ‐137G/C gene polymorphisms in patients with penicillin allergy. J Int Med Res 2011; 39: 388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pavlos R, Mallal S, Phillips E. HLA and pharmacogenetics of drug hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenomics 2012; 13: 1285–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Genin E, Chen DP, Hung SI, Sekula P, Schumacher M, Chang PY, et al. HLA‐A*31:01 and different types of carbamazepine‐induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions: an international study and meta‐analysis. Pharmacogenomics J 2014; 14: 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ozeki T, Mushiroda T, Yowang A, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Shirakata Y, et al. Genome‐wide association study identifies HLA‐A*3101 allele as a genetic risk factor for carbamazepine‐induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in Japanese population. Hum Mol Genet 2011; 20: 1034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McCormack M, Alfirevic A, Bourgeois S, Farrell JJ, Kasperaviciute D, Carrington M, et al. HLA‐A*3101 and carbamazepine‐induced hypersensitivity reactions in Europeans. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1134–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Niihara H, Kakamu T, Fujita Y, Kaneko S, Morita E. HLA‐A31 strongly associates with carbamazepine‐induced adverse drug reactions but not with carbamazepine‐induced lymphocyte proliferation in a Japanese population. J Dermatol 2012; 39: 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim SH, Lee KW, Song WJ, Kim SH, Jee YK, Lee SM, et al. Carbamazepine‐induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions and HLA genotypes in Koreans. Epilepsy Res 2011; 97: 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hung SI, Chung WH, Liou LB, Chu CC, Lin M, Huang HP, et al. HLA‐B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102: 4134–4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kaniwa N, Saito Y, Aihara M, Matsunaga K, Tohkin M, Kurose K, et al. HLA‐B locus in Japanese patients with anti‐epileptics and allopurinol‐related Stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Pharmacogenomics 2008; 9: 1617–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lonjou C, Borot N, Sekula P, Ledger N, Thomas L, Halevy S, et al. A European study of HLA‐B in Stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis related to five high‐risk drugs. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2008; 18: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tassaneeyakul W, Jantararoungtong T, Chen P, Lin PY, Tiamkao S, Khunarkornsiri U, et al. Strong association between HLA‐B*5801 and allopurinol‐induced Stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in a Thai population. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2009; 19: 704–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kang HR, Jee YK, Kim YS, Lee CH, Jung JW, Kim SH, et al. Positive and negative associations of HLA class I alleles with allopurinol‐induced SCARs in Koreans. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2011; 21: 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chan SH, Tan T. HLA and allopurinol drug eruption. Dermatologica 1989; 179: 32–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Genin E, Schumacher M, Roujeau JC, Naldi L, Liss Y, Kazma R, et al. Genome‐wide association study of Stevens‐Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Europe. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2011; 6: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Somkrua R, Eickman EE, Saokaew S, Lohitnavy M, Chaiyakunapruk N. Association of HLA‐B*5801 allele and allopurinol‐induced Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Med Genet 2011; 12: 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chung WH, Chang WC, Lee YS, Wu YY, Yang CH, Ho HC, et al. Genetic variants associated with phenytoin‐related severe cutaneous adverse reactions. JAMA 2014; 312: 525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hung SI, Chung WH, Liu ZS, Chen CH, Hsih MS, Hui RC, et al. Common risk allele in aromatic antiepileptic‐drug induced Stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Han Chinese. Pharmacogenomics 2010; 11: 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mehta TY, Prajapati LM, Mittal B, Joshi CG, Sheth JJ, Patel DB, et al. Association of HLA‐B*1502 allele and carbamazepine‐induced Stevens‐Johnson syndrome among Indians. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2009; 75: 579–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ikeda H, Takahashi Y, Yamazaki E, Fujiwara T, Kaniwa N, Saito Y, et al. HLA class I markers in Japanese patients with carbamazepine‐induced cutaneous adverse reactions. Epilepsia 2010; 51: 297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Martin AM, Nolan D, James I, Cameron P, Keller J, Moore C, et al. Predisposition to nevirapine hypersensitivity associated with HLA‐DRB1*0101 and abrogated by low CD4 T‐cell counts. AIDS 2005; 19: 97–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Littera R, Carcassi C, Masala A, Piano P, Serra P, Ortu F, et al. HLA‐dependent hypersensitivity to nevirapine in Sardinian HIV patients. AIDS 2006; 20: 1621–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gatanaga H, Yazaki H, Tanuma J, Honda M, Genka I, Teruya K, et al. HLA‐Cw8 primarily associated with hypersensitivity to nevirapine. AIDS 2007; 21: 264–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chantarangsu S, Mushiroda T, Mahasirimongkol S, Kiertiburanakul S, Sungkanuparph S, Manosuthi W, et al. HLA‐B*3505 allele is a strong predictor for nevirapine‐induced skin adverse drug reactions in HIV‐infected Thai patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2009; 19: 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Phillips E, Lucas M, Kean N, Lucas A, McKinnon E, Mallal S. HLA‐B*35 is associated with nevirapine hypersensitivity in the contemporary Western Australian HIV cohort study. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 42: 48. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Phillips EJ, Mallal SA. Pharmacogenetics of drug hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenomics 2010; 11: 973–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pichler W, Yawalkar N, Schmid S, Helbling A. Pathogenesis of drug‐induced exanthems. Allergy 2002; 57: 884–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Park BK, Naisbitt DJ, Gordon SF, Kitteringham NR, Pirmohamed M. Metabolic activation in drug allergies. Toxicology 2001; 158: 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Naisbitt DJ, Gordon SF, Pirmohamed M, Burkhart C, Cribb AE, Pichler WJ, et al. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of sulphamethoxazole: demonstration of metabolism‐dependent haptenation and T‐cell proliferation in vivo . Br J Pharmacol 2001; 133: 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. White KD, Chung WH, Hung SI, Mallal S, Phillips EJ. Evolving models of the immunopathogenesis of T cell‐mediated drug allergy: the role of host, pathogens, and drug response. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136: 219–234 quiz 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Padovan E, Mauri‐Hellweg D, Pichler WJ, Weltzien HU. T cell recognition of penicillin G: structural features determining antigenic specificity. Eur J Immunol 1996; 26: 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pichler WJ, Beeler A, Keller M, Lerch M, Posadas S, Schmid D, et al. Pharmacological interaction of drugs with immune receptors: the p‐i concept. Allergol Int 2006; 55: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Schnyder B, Mauri‐Hellweg D, Zanni M, Bettens F, Pichler WJ. Direct, MHC‐dependent presentation of the drug sulfamethoxazole to human alphabeta T cell clones. J Clin Invest 1997; 100: 136–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zanni MP, von Greyerz S, Schnyder B, Brander KA, Frutig K, Hari Y, et al. HLA‐restricted, processing‐ and metabolism‐independent pathway of drug recognition by human alpha beta T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest 1998; 102: 1591–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zanni MP, von Greyerz S, Schnyder B, Wendland T, Pichler WJ. Allele‐unrestricted presentation of lidocaine by HLA‐DR molecules to specific alphabeta+ T cell clones. Int Immunol 1998; 10: 507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Pichler WJWS. Interaction of small molecules with specific immune receptors: the p‐i concept and its consequences. Curr Immunol Rev 2014; 10: 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Bharadwaj M, Illing P, Theodossis A, Purcell AW, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J. Drug hypersensitivity and human leukocyte antigens of the major histocompatibility complex. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2012; 52: 401–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Norcross MA, Luo S, Lu L, Boyne MT, Gomarteli M, Rennels AD, et al. Abacavir induces loading of novel self‐peptides into HLA‐B*57: 01: an autoimmune model for HLA‐associated drug hypersensitivity. AIDS 2012; 26: F21–F29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Phillips EJ, Chung WH, Mockenhaupt M, Roujeau JC, Mallal SA. Drug hypersensitivity: pharmacogenetics and clinical syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127 (3 Suppl): S60–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hughes AR, Mosteller M, Bansal AT, Davies K, Haneline SA, Lai EH, et al. Association of genetic variations in HLA‐B region with hypersensitivity to abacavir in some, but not all, populations. Pharmacogenomics 2004; 5: 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Phillips EJ, Sullivan JR, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Utility of patch testing in patients with hypersensitivity syndromes associated with abacavir. AIDS 2002; 16: 2223–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Phillips EJ, Wong GA, Kaul R, Shahabi K, Nolan DA, Knowles SR, et al. Clinical and immunogenetic correlates of abacavir hypersensitivity. AIDS 2005; 19: 979–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Pavlos R, Mallal S, Ostrov D, Pompeu Y, Phillips E. Fever, rash, and systemic symptoms: understanding the role of virus and HLA in severe cutaneous drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014; 2: 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Dainichi T, Uchi H, Moroi Y, Furue M. Stevens‐Johnson syndrome, drug‐induced hypersensitivity syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis caused by allopurinol in patients with a common HLA allele: what causes the diversity? Dermatology 2007; 215: 86–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Jung JW, Song WJ, Kim YS, Joo KW, Lee KW, Kim SH, et al. HLA‐B58 can help the clinical decision on starting allopurinol in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26: 3567–3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yun J, Mattsson J, Schnyder K, Fontana S, Largiader CR, Pichler WJ, et al. Allopurinol hypersensitivity is primarily mediated by dose‐dependent oxypurinol‐specific T cell response. Clin Exp Allergy 2013; 43: 1246–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yun J, Marcaida MJ, Eriksson KK, Jamin H, Fontana S, Pichler WJ, et al. Oxypurinol directly and immediately activates the drug‐specific T cells via the preferential use of HLA‐B*58:01. J Immunol 2014; 192: 2984–2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chung WH, Chang WC, Stocker SL, Juo CG, Graham GG, Lee MH, et al. Insights into the poor prognosis of allopurinol‐induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions: the impact of renal insufficiency, high plasma levels of oxypurinol and granulysin. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 2157–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sullivan TJ, Wedner HJ, Shatz GS, Yecies LD, Parker CW. Skin testing to detect penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1981; 68: 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Blanca M, Torres MJ, Garcia JJ, Romano A, Mayorga C, de Ramon E, et al. Natural evolution of skin test sensitivity in patients allergic to beta‐lactam antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103 (5 Pt 1): 918–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Pavlos R, Mallal S, Ostrov D, Buus S, Metushi I, Peters B, et al. T cell‐mediated hypersensitivity reactions to drugs. Annu Rev Med 2015; 66: 439–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Marrone KA, Ying W, Naidoo J. Immune‐related adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016; 100: 242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel‐Vinay S, et al. Immune‐related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer 2016; 54: 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Champiat S, Lambotte O, Barreau E, Belkhir R, Berdelou A, Carbonnel F, et al. Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 559–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, Chalkias S, Gorham J, Xu Y, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1749–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA‐4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 2189–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Vetizou M, Pitt JM, Daillere R, Lepage P, Waldschmitt N, Flament C, et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA‐4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015; 350: 1079–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Carr DF, Chaponda M, Jorgensen AL, Castro EC, van Oosterhout JJ, Khoo SH, et al. Association of human leukocyte antigen alleles and nevirapine hypersensitivity in a Malawian HIV‐infected population. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56: 1330–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Yuan J, Guo S, Hall D, Cammett AM, Jayadev S, Distel M, et al. Toxicogenomics of nevirapine‐associated cutaneous and hepatic adverse events among populations of African, Asian, and European descent. AIDS 2011; 25: 1271–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Zhang FR, Liu H, Irwanto A, Fu XA, Li Y, Yu GQ, et al. HLA‐B*13:01 and the dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1620–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Kaniwa N, Saito Y, Aihara M, Matsunaga K, Tohkin M, Kurose K, et al. HLA‐B*1511 is a risk factor for carbamazepine‐induced Stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japanese patients. Epilepsia 2010; 51: 2461–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Alfirevic A, Jorgensen AL, Williamson PR, Chadwick DW, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. HLA‐B locus in Caucasian patients with carbamazepine hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenomics 2006; 7: 813–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Lin LC, Lai PC, Yang SF, Yang RC. Oxcarbazepine‐induced Stevens‐Johnson syndrome: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2009; 25: 82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. An DM, Wu XT, Hu FY, Yan B, Stefan H, Zhou D. Association study of lamotrigine‐induced cutaneous adverse reactions and HLA‐B*1502 in a Han Chinese population. Epilepsy Res 2010; 92: 226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Shi YW, Min FL, Liu XR, Zan LX, Gao MM, Yu MJ, et al. HLA‐B alleles and lamotrigine‐induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in the Han Chinese population. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2011; 109: 42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Gao S, Gui XE, Liang K, Liu Z, Hu J, Dong B. HLA‐dependent hypersensitivity reaction to nevirapine in Chinese Han HIV‐infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012; 28: 540–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Keane NM, Pavlos RK, McKinnon E, Lucas A, Rive C, Blyth CC, et al. HLA Class I restricted CD8+ and Class II restricted CD4+ T cells are implicated in the pathogenesis of nevirapine hypersensitivity. AIDS 2014; 28: 1891–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Vitezica ZG, Milpied B, Lonjou C, Borot N, Ledger TN, Lefebvre A, et al. HLA‐DRB1*01 associated with cutaneous hypersensitivity induced by nevirapine and efavirenz. AIDS 2008; 22: 540–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Likanonsakul S, Rattanatham T, Feangvad S, Uttayamakul S, Prasithsirikul W, Tunthanathip P, et al. HLA‐Cw*04 allele associated with nevirapine‐induced rash in HIV‐infected Thai patients. AIDS Res Ther 2009; 6: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]