Abstract

Levels of secretory phospholipases A2 (sPLA2) highly increase under acute and chronic inflammatory conditions. sPLA2 is mainly associated with high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and generates bioactive lysophospholipids implicated in acute and chronic inflammatory processes. Unexpectedly, pharmacological inhibition of sPLA2 in patients with acute coronary syndrome was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Given that platelets are key players in thrombosis and inflammation, we hypothesized that sPLA2-induced hydrolysis of HDL-associated phospholipids (sPLA2-HDL) generates modified HDL particles that affect platelet function. We observed that sPLA2-HDL potently and rapidly inhibited platelet aggregation induced by several agonists, P-selectin expression, GPIIb/IIIa activation and superoxide production, whereas native HDL showed little effects. sPLA2-HDL suppressed the agonist-induced rise of intracellular Ca2+ levels and phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2, which trigger key steps in promoting platelet activation. Importantly, sPLA2 in the absence of HDL showed no effects, whereas enrichment of HDL with lysophosphatidylcholines containing saturated fatty acids (the main sPLA2 products) mimicked sPLA2-HDL activities. Our findings suggest that sPLA2 generates lysophosphatidylcholine-enriched HDL particles that modulate platelet function under inflammatory conditions.

Introduction

Secretory phospholipases A2 (sPLA2) are members of the phospholipase A2 family of enzymes which hydrolyze the sn-2 ester bond in phospholipids, generating nonesterified free fatty acids and lysophospholipids. Levels of sPLA2 type IIA and to a lesser extent sPLA2 type V highly increase during the acute phase response1. Epidemiologic studies showed an association between elevated sPLA2 activity and several inflammatory diseases2–6. Thus, a great effort has been devoted to developing sPLA2 inhibitors as new agents to treat inflammatory diseases. Of particular interest, clinical trials of sPLA2 inhibitors in the therapy of acute coronary syndrome, sepsis and rheumatoid arthritis, failed to prove sPLA2 inhibition as a promising therapeutic strategy7–9. Unexpectedly, pharmacological inhibition of sPLA2 was associated with a 60% increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in the VISTA-16 clinical trial7. A subsequent Mendelian randomization study confirmed that sPLA2 was unlikely to be causal in the development of atherosclerosis10. In addition, a recent study reported increased atherosclerosis in group X sPLA2-deficient mice, raising the possibility that not all sPLA2 types drive inflammation but that certain sPLA2 subtypes may be even atheroprotective and anti-inflammatory11.

Under acute inflammatory conditions sPLA2-IIA is mainly associated with high-density lipoprotein (HDL), the principal plasma carrier of phospholipids and the major substrate for sPLA2 12, 13. Furthermore, sPLA2 types V and X, found in human and mouse atherosclerotic plaques, are highly efficient in hydrolyzing lipoprotein-associated phospholipids2. Inflammation and especially acute phase conditions can significantly influence metabolism of HDL and consequently its protein and lipid composition14. One of the characteristics of acute-phase HDL is an elevated content of lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs), generated from strongly increased sPLA2 activity15. In patients with sepsis plasma sPLA2 was almost completely associated with HDL12, which are the major source of phospholipids in plasma. In studies using a mouse model overexpressing human sPLA2-IIA, plasma levels of HDL were markedly decreased, which was accompanied by reduction in HDL particle size, suggesting that HDL is a principal substrate for sPLA2 13, 16. In addition, recombinant sPLA2-IIA and V have been shown to be more active on isolated HDL in comparison to other lipoproteins, such as LDL17.

Platelets have a key role in arterial thrombosis, the most common cause of myocardial infarction and stroke18. Accumulating evidence suggests that inflammatory responses are linked to increased platelet activation in the bloodstream of patients with systemic inflammation and sepsis19. It is well known that platelets substantially contribute to sepsis complications such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic microangiopathy and multiple organ failure20. Platelet function has been shown to be very sensitive to the influence of plasma lipoproteins and cholesterol levels21, 22. However, very little is known about the effects of inflammation-induced changes in HDL composition (especially lysophospholipid enrichment) on HDL-platelet interaction and functional responses of platelets. Pharmacological inhibition of sPLA2 resulted in increased incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke7, raising the possibility that increased sPLA2 activity during inflammation might modulate platelet activity. Based on these observations, we tested whether sPLA2-induced hydrolysis of HDL-associated phospholipids generates particles that affect platelet functionality. Our findings suggest sPLA2-modified HDL particles potently suppress agonist induced platelet activation.

Results

sPLA2-modified HDL rapidly suppresses agonist induced platelet aggregation

In order to generate sPLA2-modified HDL, native HDL (nHDL) isolated from plasma of healthy human volunteers was treated with human recombinant sPLA2 type V. The reaction was stopped by addition of the sPLA2 type V inhibitor varespladib. Treatment of HDL with sPLA2 for 90 min (sPLA2-HDL-low) and overnight treatment (sPLA2-HDL-high) hydrolyzed ~30–40% and 70–80% of HDL-associated phosphatidylcholines, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1).

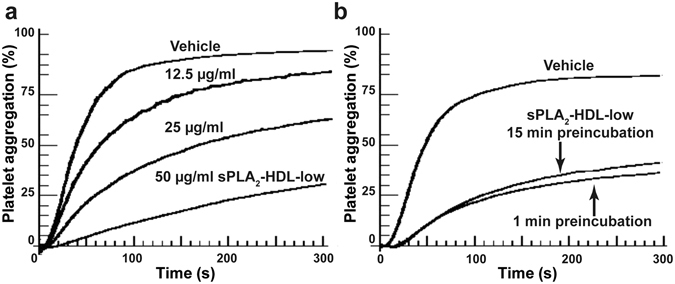

To test whether sPLA2-HDL affects platelet aggregation, platelets isolated from plasma of healthy donors were exposed to different agonists including ADP, collagen and thrombin in the presence or absence of native HDL and sPLA2-HDL. Strikingly, sPLA2-HDL potently inhibited platelet aggregation induced by ADP, collagen and thrombin, whereas sPLA2 in the absence of HDL and the sPLA2 inhibitor varespladib showed no effect (Fig. 1a–d). sPLA2-HDL-mediated inhibition of platelet aggregation was concentration dependent (Fig. 2a) and aggregation was significantly decreased already after one minute pre-treatment of platelets with sPLA2-HDL (Fig. 2b). Importantly, Annexin-V staining of phosphatidylserine surface expression confirmed that sPLA2-HDL did not affect platelet viability (Supplementary Figure 2). Furthermore, since it has been shown that HDL isolation procedure can have a significant impact on HDL composition23, we tested whether HDL isolated by a different method will have the same effects on platelets. Therefore, we isolated HDL from human plasma by dextran-sulfate precipitation24. We found that HDL isolated by dextran-sulfate precipitation also inhibited platelet activation after sPLA2-mediated modification (Supplementary Figure 3), whereas native HDL showed no effect.

Figure 1.

sPLA2-treated HDL inhibits ADP-, thrombin- and collagen-induced platelet aggregation. HDL was treated with sPLA2 for either 90 min (sPLA2-HDL-low) or overnight (sPLA2-HDL-high) in order to hydrolyse HDL-associated phospholipids. Platelets were preincubated with vehicle, native HDL (nHDL, 50 µg/mL), sPLA2-HDL-low (50 µg/mL), sPLA2-HDL-high (50 µg/mL), sPLA2 or varespladib. Subsequently, platelets were stimulated with (a,b) ADP (c) collagen or (d) thrombin in concentrations which induced 70–90% aggregation in vehicle-stimulated platelets. (a,c,d) Values are expressed as % of maximal platelet aggregation. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus vehicle. (b) Time course of one representative recording of ADP-induced aggregation is shown.

Figure 2.

Concentration and time dependence of sPLA2-HDL-mediated inhibition of platelet aggregation. (a) Platelets were pretreated with vehicle or increasing concentrations of sPLA2-HDL-low (0 up to 50 µg/mL). (b) Platelets were preincubated with vehicle or sPLA2-HDL-low (50 µg/mL) for 1 or 15 min. Subsequently, platelets were stimulated with ADP in concentration which induced 70–90% aggregation in vehicle-stimulated platelets. Values are expressed as % of maximal platelet aggregation. One representative experiment out of three independent experiments is shown.

sPLA2-HDL inhibits P-selectin expression, GPIIb/IIIa activation and superoxide production in platelets

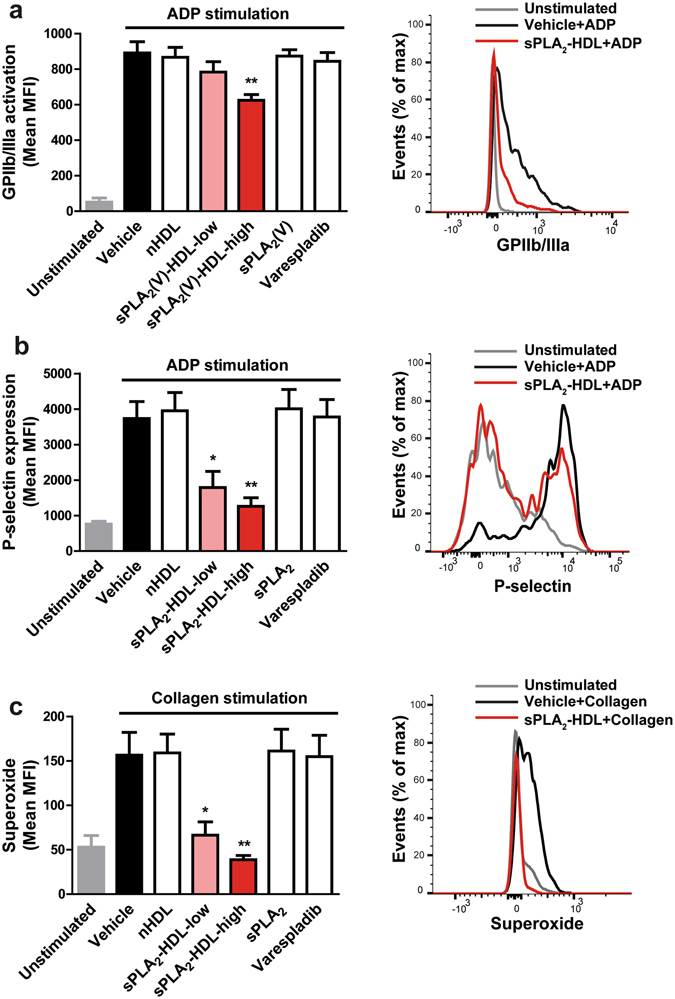

Furthermore, we assessed platelet functional responses involved in hemostatic and immune platelet functions, such as P-selectin expression, integrin activation, and reactive oxygen species production. Notably, sPLA2-HDL inhibited activation of the main platelet integrin GPIIb/IIIa (Fig. 3a) as well as surface exposure of the platelet activation marker P-selectin (Fig. 3b). Upon activation, platelets produce reactive oxygen species which promote their recruitment to a growing thrombus25. Importantly, sPLA2-HDL significantly attenuated superoxide anion production by platelets (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

sPLA2-HDL inhibits P-selectin expression, GPIIb/IIIa activation and superoxide production in platelets. Platelets were pretreated with vehicle, native HDL (nHDL, 50 µg/mL), sPLA2-HDL-low (50 µg/mL), sPLA2-HDL-high (50 µg/mL), sPLA2 or varespladib. (a) For GPIIb/IIIa activation platelets were stimulated with ADP (3 µM). (b) Surface expression of P-selectin was induced with ADP (3 µM) in the presence of cytochalasin B (5 µg/mL) (c) Superoxide production was induced with 5 µg/mL collagen. (a–c) GPIIb/IIIa activation, P-selectin expression and superoxide production were measured by flow cytometry. Bar graphs on the left represent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 4–6). Representative flow cytometry histograms of platelets pretreated with sPLA2-HDL-high are displayed on the right. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus vehicle-pretreated and (a,b) ADP or (c) collagen-stimulated platelets.

sPLA2-generated lysophosphatidylcholines mediate effects of sPLA2-HDL on platelets

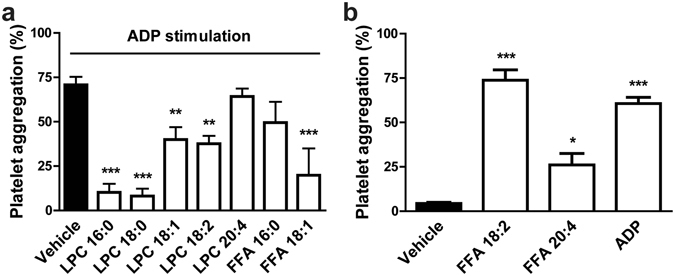

In comparison to native HDL, sPLA2-modified HDL contains significantly higher amounts of LPCs (Supplementary Figure 1b). In order to investigate whether HDL-bound LPCs are the active moiety of sPLA2-HDL, native HDL was enriched with different LPC species. Saturated LPC species (16:0 and 18:0) are the most abundant LPC species in sPLA2-HDL and account for about 70% of total LPCs (Supplementary Figure 1b). Importantly, when enriched in HDL, LPCs mimicked the effects of sPLA2-HDL, with LPC 16:0 and LPC 18:0 being the most potent mediators (Fig. 4a). In addition, other LPCs species (LPC 18:1 and LPC 18:2) as well as free fatty acid (FFA) 18:1 were able to inhibit platelet aggregation, but to a much weaker extent (Fig. 4a). These results indicate that several LPCs and some FFA species contribute to the effects of sPLA2-HDL on platelets. In sharp contrast, FFA 18:2 and FFA 20:4 induced platelet aggregation when enriched in HDL (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

HDL-associated LPCs mediate sPLA2-HDL effects on platelets. (a) Washed platelets were preincubated with vehicle or HDL enriched with different LPCs (16:0, 18:0, 18:1, 18:2, 20:4) or FFAs (16:0, 18:1). Subsequently, platelets were stimulated with ADP inducing 70–90% aggregation in vehicle-stimulated platelets. (b) Platelets were stimulated with vehicle, HDL enriched with FFA 18:2, HDL enriched with FFA 20:4 or with ADP (20 µM) as a positive control and the aggregation was recorded. Values are expressed as % of maximal platelet aggregation. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus vehicle.Results shown are mean ± SEM (n = 3).

sPLA2-HDL suppresses agonist-induced Ca2+ flux and inhibits kinase phosphorylation in platelets

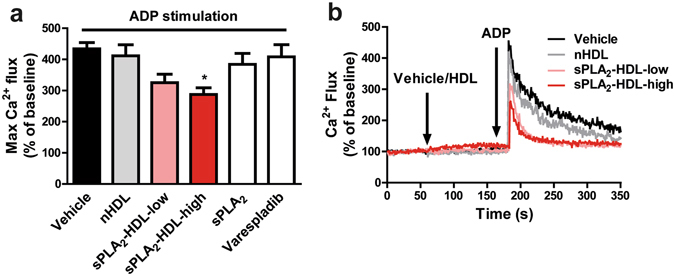

To gain insights into the signaling pathways involved in sPLA2-HDL effects on platelets, we examined intracellular signaling events such as release of Ca2+ (Ca2+ flux) and phosphorylation of protein kinases, both of which play a crucial role in platelet activation cascades. First, we assessed agonist induced changes in Ca2+ flux. ADP stimulation leads to a rise in intracellular Ca2+ in platelets, which was significantly suppressed upon sPLA2-HDL treatment (Fig. 5a,b).

Figure 5.

sPLA2-HDL inhibits Ca2+ flux in platelets. Baseline Ca2+ levels were measured by flow cytometry for 1 min and then platelets were treated either with vehicle, nHDL (50 µg/mL), sPLA2-HDL-low (50 µg/mL), sPLA2-HDL-high (50 µg/mL), sPLA2 or varespladib for 2 min. Ca2+ flux was subsequently induced with ADP as indicated by the arrow (10 µM). (a) Values are normalized to the baseline and expressed as maximal Ca2+ flux upon ADP stimulation. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 4). Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle-pretreated and ADP-stimulated platelets. (b) One representative recording of Ca2+ flux is shown.

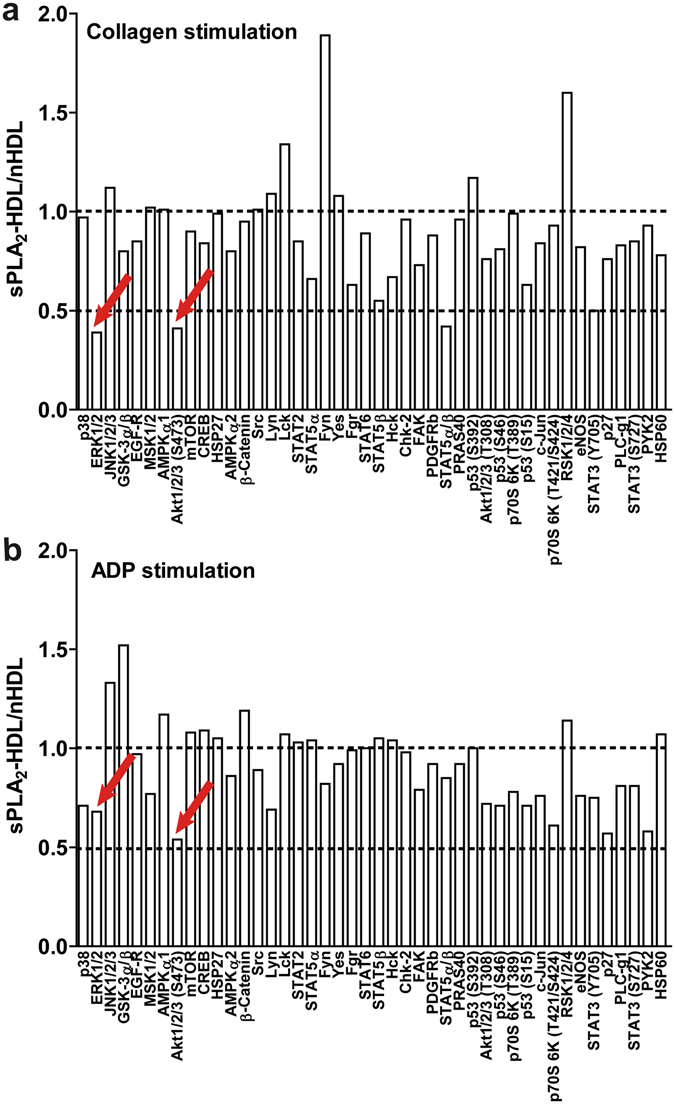

To identify sPLA2-HDL modulated signaling cascades, we screened the phosphorylation status of kinases (including p38 MAPK, Akt, eNOS, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, members of the Src family kinases, GSK-3α/β, AMPK, STAT3) important in platelet activation. For that purpose, platelets were activated with the platelet agonists collagen or ADP in presence of sPLA2-HDL or control HDL. We observed that in comparison to control HDL-treated platelets, phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and ERK1/2 was significantly decreased in both collagen and ADP-stimulated platelets pre-treated with sPLA2-HDL (Fig. 6). Effects of sPLA2-HDL on Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were further confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Figure 4). These data suggest that inhibition of Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation by sPLA2-HDL is involved in the observed anti-aggregatory effects. Both, phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 are well known to induce platelet activation26–28.

Figure 6.

Proteome profiler analysis of nHDL and sPLA2-HDL-treated platelets. Platelets were preincubated with nHDL (50 µg/mL) or sPLA2-HDL-high (50 µg/mL) and stimulated with (a) ADP (10 µM) or (b) collagen (5 µg/mL). Kinase phosphorylation was assessed using human phospho-kinase antibody array. Values are expressed as fold increase over nHDL-treated platelets. A twofold increase/decrease in phosphorylation was considered to be significant. One representative experiment out of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Figure 7.

sPLA2-HDL inhibits Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in platelets. Platelets were pretreated with vehicle, nHDL (50 µg/mL), sPLA2-HDL-low (50 µg/mL) or sPLA2-HDL-high (50 µg/mL). Subsequently cells were stimulated with (a,c) ADP (10 µM) or (b,d) collagen (5 µg/mL). (a,b) Akt (Ser473) and (c,d) ERK1/2 phosphorylation was assessed by Western blot. β-actin was used as the loading control. Blots have been cropped from full-length blots shown in Supplementary Figure 4. ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System and ECL Blotting Substrate (both Bio-Rad, Vienna, Austria) were used to visualize protein bands. Immunoblot images were quantified using Image Lab 5.2 software (Bio-Rad). Statistical analysis of phospho-Akt (p-Akt)/total Akt (t-Akt) and phospho-ERK1/2 (p-ERK)/total ERK1/2 (t-ERK) ratios were derived from 3 independent experiments which were run under the same conditions. Vehicle treated (unstimulated) control was set as baseline and values are expressed as % over baseline. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus vehicle-pretreated and (a,c) ADP or (b,d) collagen-stimulated platelets.

Discussion

Increasing evidence suggests that HDL exerts its cardioprotective, antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory roles via direct immunomodulatory effects on several cell types including macrophages, neutrophils and endothelial cells29–32. Furthermore, HDL can actively interact with platelets, which results in modulation of platelet function21, 33–35. Most investigations showed inhibitory effects of native HDL on platelets22. However, there are also studies showing no effect or even pro-aggregatory activity of native HDL36, 37.

Previous studies reported that agonist-induced platelet aggregation is suppressed when platelets are exposed to mildly oxidized HDL38–40. In line with these previous studies, we show that sPLA2-mediated modification of HDL does not impair its anti-aggregatory activities towards platelets, but rather generates particles with increased ability to rapidly and potently suppress platelet activation. It is well known that mild oxidation generates LPCs41, 42. Therefore, it is likely that the anti-aggregatory activities observed with oxidized HDL38–40 are mediated, at least in part, by HDL associated LPCs.

sPLA2-HDL inhibited platelet activation induced by a wide range of physiological agonists including ADP, collagen and thrombin in a concentration-dependent manner. Interestingly, in our experiments, native HDL showed only minimal effects and sPLA2 in the absence of HDL showed no effect on agonist-induced activation of platelets. Therefore, our results clearly suggest that a certain threshold of HDL-associated LPC is required to suppress platelet activation. To keep the LPC content of control HDL low, we used HDL that was rapidly isolated within a few hours by using gradient ultracentrifugation43–45 from blood obtained from blood donors within one day. We obtained very similar results when HDL was isolated by dextran sulfate precipitation, clearly suggesting that the rapid gradient ultracentrifugation procedure to isolate HDL does not markedly affect the LPC content of HDL. A rapid isolation procedure and usage of HDL is of critical importance, given that HDL-associated lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 constantly produce LPC. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the LPC content of native HDL used in different studies can determine the anti-aggregatory activities of HDL46–48.

Beside aggregation, sPLA2-HDL inhibited other platelet functional responses such as integrin GPIIb/IIIa activation and P-selectin expression. This is of importance given that these proteins not only mediate hemostatic and prothrombotic platelet functions, but also their immune interactions, such as activation of endothelium, formation of platelet-leukocyte complexes and priming of neutrophils to produce neutrophil extracellular traps49–51. In addition, activated platelets produce reactive oxygens species which are involved in platelet intracellular signaling, as well as platelet recruitment and thrombus growth when released from platelets25, 52. Importantly, sPLA2-HDL was able to significantly suppress platelet superoxide anion production.

Physiological levels of LPCs in the circulation are high (around 190 µM)53 and can reach even mM levels in some pathophysiological states, such as hyperlipidemia54. LPCs have been regarded to be involved in the etiology of several chronic inflammatory diseases including autoimmune diseases and atherosclerosis55. On the other hand, administration of LPC significantly reduced sepsis-induced mortality in mice56. In line with this study, septic patients show positive association between serum LPC levels and survival57. Biological activities of free LPC on endothelial and immune cells have been shown in many studies55, 58. Although LPC might be transiently found in its free form, it is predominantly bound to albumin, other serum proteins and lipoproteins55. The albumin-bound fraction represents an inactive form of LPC since albumin abolishes most of LPC cellular effects59. Interestingly, physiological activity of lipoprotein-bound LPC is not well investigated. In comparison to low-density lipoproteins, HDL carries higher amounts of LPC60, 61 because HDL-associated lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase constantly produces LPC. Moreover, HDL has the ability to efficiently remove saturated and monounsaturated LPCs from low-density lipoproteins62. Of particular interest, deficiency in lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase, which is the main enzyme involved in formation of HDL-associated lysophospholipids under physiological conditions63, decreased LPS-neutralizing capacity of HDL and enhanced LPS-induced inflammation in mice64. In line with these observations, we previously showed that sPLA2-HDL has potent anti-inflammatory effects on neutrophils65, indicating that HDL-bound LPCs represent a biologically active LPC fraction.

Importantly, HDL enriched with LPC 16:0 and LPC 18:0, which are the most abundant LPC species in sPLA2-HDL, mimicked the effects of sPLA2-treated HDL on platelets. Other LPC species (LPC 18:1 and LPC 18:2) and some FFAs (FFA 18:1), showed weaker inhibitory activity when enriched in HDL. This suggests that other sPLA2-generated products contribute to the sPLA2-HDL activity on platelets. In addition, sPLA2-HDL carries a certain amount of pro-aggregatory mediators such as arachidonic acid66, which induced platelet aggregation when enriched in HDL. However, their activity seems to be completely counteracted by HDL-associated LPCs. Given that the sPLA2 group of enzymes comprises several subtypes with different substrate specifities67, various LPC and FFA species are expected to be formed und inflammatory conditions that might generate sPLA2-HDL with diverse effects on platelets.

Of particular interest, we observed that sPLA2-HDL effectively suppressed agonist-induced rise in intracellular Ca2+ as well as phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and ERK1/2. Importantly, Akt and ERK play a significant role in platelet secretory pathways leading to granule release. Additionally they are involved in regulation of integrin GPIIb/IIIa function26–28. ERK has been shown to phosphorylate and activate cytoplasmic phospholipase A2, an enzyme responsible for thromboxane A2 synthesis68. Furthermore, phosphorylation of certain kinases, such as Akt, depends on the interaction with membrane cholesterol-rich microdomains69. We have recently shown that sPLA2-HDL depicts an increased cholesterol-mobilizing capacity and disrupts membrane cholesterol-rich microdomains in neutrophils65. Given that changes in membrane cholesterol content highly influence platelet functionality70, we expect that sPLA2-HDL-mediated cholesterol depletion might also be involved in observed inhibitory effects on agonist-induced platelet activation.

A potential limitation of the present study is that we only assessed the impact of sPLA2 on HDL functionality, while under inflammatory conditions HDL particles are subjected to an array of complex proteomic and lipidomic changes that affect HDL function60, 61. However, our study clearly demonstrates that upon modification by sPLA2, HDL is transformed into a particle with a strong ability to modulate platelet activation via suppression of intracellular Ca2+ increase and inhibition of Akt and ERK1/2 kinase phosphorylation. Our results may, therefore, contribute to a better understanding of the role of sPLA2 in atherosclerosis and inflammation.

Materials and Methods

All reagents were from Sigma (Vienna, Austria), unless otherwise specified. Human recombinant secretory phospholipase A2 type V was purchased from Cayman Europe (Tallin, Estonia). Varespladib was purchased from Eubio (Vienna, Austria). Fluo-3-AM was from Life Technologies (Vienna, Austria). ADP, collagen and thrombin were purchased from Probe&Go (Osburg, Germany). sn-1 LPCs (16:0, 18:0, 18:1, 18:2 and 20:4) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Birmingham, AL, USA). CellFix, FACS-Flow, Annexin V, FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD62P (P-selectin) antibody and FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human PAC-1 antibody were from BD Bioscience (Vienna, Austria). Antibodies against ERK1/2 (#9102), phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (#9101), Akt (#9272), phospho-Akt (Ser 473) (#9271) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers MA, USA). β-actin antibody (A5316) was from Sigma (Vienna, Austria). HRP-linked goat-anti mouse (#115-036-062) and goat-anti rabbit (#111-036-045) secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, USA). Fixative solution was prepared by adding 9 mL distilled water and 30 mL FACS-Flow to 1 mL CellFix.

Blood collection

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Graz. All volunteers signed an informed consent form in agreement with the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Graz. All methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Blood was collected into tubes with 3.8% (w/v) sodium citrate and platelet rich plasma (PRP) was obtained by centrifugation at 400 × g for 20 min at RT as described71, 72. Subsequently, plasma was used for HDL and platelet isolation.

HDL isolation

HDL was isolated by density gradient ultracentrifugation as described43–45. Plasma density was adjusted with potassium bromide to 1.24 g/mL and a two-step density gradient was generated in centrifuge tubes (16 × 76 mm, Beckman) by layering the density-adjusted plasma (1.24 g/mL) underneath a NaCl-density solution (1.063 g/mL). Tubes were sealed and centrifuged at 90,000 rpm for 4 h in a 90Ti fixed angle rotor (Beckman Instruments, Krefeld, Germany). After centrifugation, the HDL-containing band was collected and desalted via PD10 columns (GE Healthcare, Vienna, Austria) and immediately used for experiments.

sPLA2 treatment of HDL

HDL was incubated in the presence of 400 ng/mL human recombinant type V sPLA2 in PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ at 37 °C for either 90 min (low modification) or overnight (high modification) in order to hydrolyse HDL-associated phospholipids. The reaction was stopped by addition of sPLA2 inhibitor varespladib (1 µM).

Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) and free-fatty acid (FFA) enrichment of HDL

FFAs were dissolved in ethanol and LPCs in chloroform/methanol and stored at −20 °C under argon atmosphere. Required amounts of LPC were dried under a stream of nitrogen and re-dissolved in PBS. In order to generate LPC- or FFA-enriched HDL, 1 mg/mL HDL was incubated with 0.6 mmol/L 16:0, 18:1, 18:2 or 20:4 FFA or with 0.6 mmol/L 16:0, 18:1, 18:2 or 20:4 LPC for 2 h at 37 °C. Unbound LPCs and FFAs were removed by gel filtration. Content of HDL-associated LPCs was assessed by Azwell LPC Assay Kit (Hölzl Diagnostika) and FFA content was were determined using non-esterified fatty acids kit (Diasys, Holzheim, Germany).

Platelet preparation

Platelets from platelet rich plasma were sedimented by centrifugation (1000 × g for 15 min at RT). Subsequently, platelets washed twice with a low pH platelet wash buffer (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM KCl, 0.9 mM Na2HPO4, 2.1 mM MgCl2, 22 mM C6H5Na3O7, 0.055 mM glucose monohydrate and 0.35% bovine serum albumin, pH = 6.5) by centrifugation (1000 × g for 15 min at RT). The final platelet preparation was resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer (10 mM HEPES, 134 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 12 mM NaHCO3, 2.9 mM KCl, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.055 mM glucose, pH = 7.4) and used for functional platelet assays.

Platelet aggregation

Platelet aggregation was performed at 37 °C with constant stirring (1000 rpm) using the four-channel platelet aggregometer APACT4004 (LABiTec, Ahrensburg, Germany), which works on the principle of light transmission, as previously described71, 73. Platelet response to a concentration range of ADP (5–20 µM), collagen (2.5–10 µg/mL) or thrombin (0.05–0.1 U/mL) was tested before each experiment. ADP, collagen and thrombin concentrations which induced 70–90% aggregation were used for platelet stimulation. Platelets were preincubated with vehicle or HDL samples for 5 min at 37 °C. Aggregation was induced with ADP in the presence of 1 µg/mL fibrinogen, collagen or thrombin and measured for 5 min. Data were expressed as percentage of maximum light transmission, with non-stimulated washed platelets being 0% and Tyrode’s buffer 100% aggregation71, 72.

P-selectin (CD62P) expression

Washed platelets resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer were preincubated with vehicle, HDL samples (50 µg/mL), sPLA2 (400 ng/mL) or varespladib (1 µM) for 10 min at RT. Subsequently, cells were stimulated with ADP (3 µM) in the presence of cytochalasin B (5 µg/mL) for 30 min at RT in the presence of anti-CD62P-FITC conjugated antibody. Cytochalasin B was used to facilitate translocation of P-selectin from granules to the cell surface. The samples were fixed and P-selectin upregulation was detected by flow cytometry.

GPIIb/IIIa (PAC-1) activation

PRP was suspended in Tyrode’s buffer and pretreated with vehicle, HDL samples (50 µg/mL), sPLA2 (400 ng/mL) or varespladib (1 µM) for 10 min at RT. The activation of glycoprotein receptor GPIIb/IIIa was induced with ADP (3 µM) for 30 min at RT in the presence of the FITC-conjugated anti-PAC-1 antibody that recognizes a conformation-dependent determinant on the GPIIb/IIIa complex. The samples were fixed and GPIIb/IIIa activation was detected by flow cytometry.

Superoxide production

Washed platelets (1 × 107 per sample) resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer were pretreated with vehicle, HDL samples (50 µg/mL), sPLA2 (400 ng/mL) or varespladib (1 µM) for 10 min at 37 °C and stimulated with collagen (5 µg/mL) for 20 min, at 37 °C. Superoxide production was detected with Superoxide Detection Kit according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, after the treatment platelets were washed once, resuspended in superoxide detection reagent and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. Superoxide production was measured immediately by flow cytometry as an increase in fluorescence intensity (FL-2 channel).

Ca2+ Flux

Platelet-rich plasma was loaded with the cell membrane permeable Ca2+-sensitive dye Fluo-3-AM (5 µM) in the presence of 2.5 mM probenecid for 30 min at 37 °C and resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer (1.5 µL of PRP/500 µL buffer). Changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels in platelets were measured by flow cytometry as an increase in fluorescence intensity of Fluo-3-AM in FL-1 channel.

Phosphokinase array

Analysis of phosphorylation profiles of kinases and their protein substrates was done by the Human Phospho-Kinase Array (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Washed platelets were pretreated with nHDL (50 µg/mL) or sPLA2-HDL-high (50 µg/mL) for 5 min at RT, stimulated with collagen (5 µg/mL) or ADP (10 µM) for 5 min at RT and analyzed according to manufacturer’s protocol. The membranes were imaged using ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System and ECL Blotting Substrate (both Bio-Rad, Vienna, Austria). The average signal (pixel density) analysis of duplicate spots representing each protein was performed using Image Lab 5.2 software (Bio-Rad). A twofold increase/decrease in phosphorylation was considered to be significant.

Western blot analysis

Washed platelets were pretreated with vehicle, nHDL (50 µg/mL), sPLA2-HDL-low (50 µg/mL) or sPLA2-HDL-high (50 µg/mL) for 5 min at RT and stimulated with either ADP (10 µM) or collagen (5 µg/mL) for 5 min at RT. Subsequently 6X Laemmli buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol was added and samples were denaturated for 5 min at 95 °C. Equal amounts of protein were submitted to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS/PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was cut into two parts in order to enable blotting for multiple antibodies. After blocking unspecific binding sites with a blocking buffer (137 NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 0.1% Tween-20. pH 7.6, with 5% milk powder), the upper part of the membrane was incubated with primary rabbit anti-phospho Akt antibody (1:1000) and the lower part with anti-phospho ERK1/2 antibody (1:1000) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were rinsed and subsequently incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary Abs (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. Before probing with anti-ERK1/2 or anti-Akt primary antibodies (1:1000, overnight at 4 °C), membranes were stripped for 30 min at 50 °C using a stripping buffer (100 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8). As a loading control membranes were incubated with mouse anti-β-actin primary antibody (1:7500) overnight at 4 °C. ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System and ECL Blotting Substrate (both Bio-Rad, Vienna, Austria) were used to visualize protein bands. Immunoblot images were quantified using Image Lab 5.2 software (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as mean ± SEM for n separate experiments. Experiments were repeated three to six times using platelets from different donors. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism Version 5. Comparisons of groups were performed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test. Significances were accepted at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the by the Austrian National Bank (15883 to M.H) and the Austrian Science Fund FWF (DK-MOLIN – W1241, P22976-B18 to G.M. and KLI521-B31 to R.S.).

Author Contributions

S.C. and G.M. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S.C., L.P., E.K. and T.O.E. performed the experiments. S.C. prepared all figures. M.H., R.S., R.Z., S.F., A.H. and G.M. analyzed and interpreted data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08136-1

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mallat Z, Lambeau G, Tedgui A. Lipoprotein-associated and secreted phospholipases A(2) in cardiovascular disease: roles as biological effectors and biomarkers. Circulation. 2010;122:2183–2200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.936393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambeau G, Gelb MH. Biochemistry and physiology of mammalian secreted phospholipases A2. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:495–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.062405.154007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nevalainen TJ. Serum phospholipases A2 in inflammatory diseases. Clin. Chem. 1993;39:2453–2459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin MK, et al. Secretory phospholipase A2 as an index of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Prospective double blind study of 212 patients. J. Rheumatol. 1996;23:1162–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koenig W, et al. Association between type II secretory phospholipase A2 plasma concentrations and activity and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2009;30:2742–2748. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenson RS, Hurt-Camejo E. Phospholipase A2 enzymes and the risk of atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2899–2909. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicholls SJ, et al. Varespladib and cardiovascular events in patients with an acute coronary syndrome: the VISTA-16 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:252–262. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeiher BG, et al. LY315920NA/S-5920, a selective inhibitor of group IIA secretory phospholipase A2, fails to improve clinical outcome for patients with severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2005;33:1741–1748. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000171540.54520.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley JD, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial of LY333013, a selective inhibitor of group II secretory phospholipase A2, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2005;32:417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes MV, et al. Secretory phospholipase A(2)-IIA and cardiovascular disease: a mendelian randomization study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:1966–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ait-Oufella H, et al. Group X secreted phospholipase A2 limits the development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-null mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:466–473. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gijon MA, Perez C, Mendez E, Sanchez Crespo M. Phospholipase A2 from plasma of patients with septic shock is associated with high-density lipoproteins and C3 anaphylatoxin: some implications for its functional role. Biochem. J. 1995;306(Pt 1):167–175. doi: 10.1042/bj3060167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tietge UJ, et al. Human secretory phospholipase A2 mediates decreased plasma levels of HDL cholesterol and apoA-I in response to inflammation in human apoA-I transgenic mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002;22:1213–1218. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000023228.90866.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khovidhunkit W, Memon RA, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Infection and inflammation-induced proatherogenic changes of lipoproteins. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 3):S462–72. doi: 10.1086/315611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pruzanski W, et al. Comparative analysis of lipid composition of normal and acute-phase high density lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 2000;41:1035–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Beer FC, et al. Secretory non-pancreatic phospholipase A2: influence on lipoprotein metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 1997;38:2232–2239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gesquiere L, Cho W, Subbaiah PV. Role of group IIa and group V secretory phospholipases A(2) in the metabolism of lipoproteins. Substrate specificities of the enzymes and the regulation of their activities by sphingomyelin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4911–4920. doi: 10.1021/bi015757x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gawaz M. Role of platelets in coronary thrombosis and reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;61:498–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russwurm S, et al. Platelet and leukocyte activation correlate with the severity of septic organ dysfunction. Shock. 2002;17:263–268. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent JL, Yagushi A, Pradier O. Platelet function in sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2002;30:S313–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aviram M, Brook JG. Platelet activation by plasma lipoproteins. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1987;30:61–72. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(87)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nofer JR, Brodde MF, Kehrel BE. High-density lipoproteins, platelets and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2010;37:726–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.05377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holzer M, et al. Refined purification strategy for reliable proteomic profiling of HDL2/3: Impact on proteomic complexity. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38533. doi: 10.1038/srep38533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burstein M, Scholnick HR, Morfin R. Rapid method for the isolation of lipoproteins from human serum by precipitation with polyanions. J. Lipid Res. 1970;11:583–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krotz F, et al. NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent platelet superoxide anion release increases platelet recruitment. Blood. 2002;100:917–924. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woulfe DS. Akt signaling in platelets and thrombosis. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2010;3:81–91. doi: 10.1586/ehm.09.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z, Zhang G, Feil R, Han J, Du X. Sequential activation of p38 and ERK pathways by cGMP-dependent protein kinase leading to activation of the platelet integrin alphaIIb beta3. Blood. 2006;107:965–972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flevaris P, et al. Two distinct roles of mitogen-activated protein kinases in platelets and a novel Rac1-MAPK-dependent integrin outside-in retractile signaling pathway. Blood. 2009;113:893–901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catapano AL, Pirillo A, Bonacina F, Norata GD. HDL in innate and adaptive immunity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014;103:372–383. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kontush, A. HDL-mediated mechanisms of protection in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Murphy AJ, et al. Neutrophil activation is attenuated by high-density lipoprotein and apolipoprotein A-I in in vitro and in vivo models of inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31:1333–1341. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy AJ, et al. High-density lipoprotein reduces the human monocyte inflammatory response. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:2071–2077. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Surya II, Akkerman JW. The influence of lipoproteins on blood platelets. Am. Heart J. 1993;125:272–275. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90096-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegel-Axel D, Daub K, Seizer P, Lindemann S, Gawaz M. Platelet lipoprotein interplay: trigger of foam cell formation and driver of atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008;78:8–17. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtiss LK, Plow EF. Interaction of plasma lipoproteins with human platelets. Blood. 1984;64:365–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassall DG, Owen JS, Bruckdorfer KR. The aggregation of isolated human platelets in the presence of lipoproteins and prostacyclin. Biochem. J. 1983;216:43–49. doi: 10.1042/bj2160043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korporaal SJ, Akkerman JW. Platelet activation by low density lipoprotein and high density lipoprotein. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 2006;35:270–280. doi: 10.1159/000093220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valiyaveettil M, et al. Oxidized high-density lipoprotein inhibits platelet activation and aggregation via scavenger receptor BI. Blood. 2008;111:1962–1971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le QH, et al. Glycoxidized HDL, HDL enriched with oxidized phospholipids and HDL from diabetic patients inhibit platelet function. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100:2006–2014. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tafelmeier, M. et al. Mildly oxidized HDL decrease agonist-induced platelet aggregation and release of pro-coagulant platelet extracellular vesicles. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Tew DG, et al. Purification, properties, sequencing, and cloning of a lipoprotein-associated, serine-dependent phospholipase involved in the oxidative modification of low-density lipoproteins. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996;16:591–599. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.16.4.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi J, et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine is generated by spontaneous deacylation of oxidized phospholipids. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:111–118. doi: 10.1021/tx100305b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holzer M, et al. Aging affects high-density lipoprotein composition and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1831:1442–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holzer M, et al. Myeloperoxidase-derived chlorinating species induce protein carbamylation through decomposition of thiocyanate and urea: novel pathways generating dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;17:1043–1052. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holzer M, et al. Anti-psoriatic therapy recovers high-density lipoprotein composition and function. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2014;134:635–642. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nofer JR, et al. HDL3-mediated inhibition of thrombin-induced platelet aggregation and fibrinogen binding occurs via decreased production of phosphoinositide-derived second messengers 1,2-diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-tris-phosphate. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998;18:861–869. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.18.6.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi Y, et al. Native lipoproteins inhibit platelet activation induced by oxidized lipoproteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;222:453–459. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen LY, Mehta JL. Inhibitory effect of high-density lipoprotein on platelet function is mediated by increase in nitric oxide synthase activity in platelets. Life Sci. 1994;55:1815–1821. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner DD, Burger PC. Platelets in inflammation and thrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:2131–2137. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000095974.95122.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Hundelshausen P, Weber C. Platelets as immune cells: bridging inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2007;100:27–40. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252802.25497.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duerschmied D, Bode C, Ahrens I. Immune functions of platelets. Thromb. Haemost. 2014;112:678–691. doi: 10.1160/TH14-02-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sill JC, Proper JA, Johnson ME, Uhl CB, Katusic ZS. Reactive oxygen species and human platelet GP IIb/IIIa receptor activation. Platelets. 2007;18:613–619. doi: 10.1080/09537100701481385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ojala PJ, Hirvonen TE, Hermansson M, Somerharju P, Parkkinen J. Acyl chain-dependent effect of lysophosphatidylcholine on human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007;82:1501–1509. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0507292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen L, et al. Oxidative modification of low density lipoprotein in normal and hyperlipidemic patients: effect of lysophosphatidylcholine composition on vascular relaxation. J. Lipid Res. 1997;38:546–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kabarowski JH. G2A and LPC: regulatory functions in immunity. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;89:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yan JJ, et al. Therapeutic effects of lysophosphatidylcholine in experimental sepsis. Nat. Med. 2004;10:161–167. doi: 10.1038/nm989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drobnik W, et al. Plasma ceramide and lysophosphatidylcholine inversely correlate with mortality in sepsis patients. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:754–761. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200401-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kabarowski JH, Xu Y, Witte ON. Lysophosphatidylcholine as a ligand for immunoregulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:161–167. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim YL, Im YJ, Ha NC, Im DS. Albumin inhibits cytotoxic activity of lysophosphatidylcholine by direct binding. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;83:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Birner-Gruenberger R, Schittmayer M, Holzer M, Marsche G. Understanding high-density lipoprotein function in disease: Recent advances in proteomics unravel the complexity of its composition and biology. Prog. Lipid Res. 2014;56C:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kontush A, Lhomme M, Chapman MJ. Unraveling the complexities of the HDL lipidome. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54:2950–2963. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rasmiena AA, Barlow CK, Ng TW, Tull D, Meikle PJ. High density lipoprotein efficiently accepts surface but not internal oxidised lipids from oxidised low density lipoprotein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1861:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Croset M, Brossard N, Polette A, Lagarde M. Characterization of plasma unsaturated lysophosphatidylcholines in human and rat. Biochem. J. 2000;345(Pt 1):61–67. doi: 10.1042/bj3450061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petropoulou PI, et al. Lack of LCAT reduces the LPS-neutralizing capacity of HDL and enhances LPS-induced inflammation in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1852:2106–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Curcic S, et al. Neutrophil effector responses are suppressed by secretory phospholipase A modified HDL. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1851:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Silver MJ, Smith JB, Ingerman C, Kocsis JJ. Arachidonic acid-induced human platelet aggregation and prostaglandin formation. Prostaglandins. 1973;4:863–875. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(73)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pruzanski W, et al. Differential hydrolysis of molecular species of lipoprotein phosphatidylcholine by groups IIA, V and X secretory phospholipases A2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1736:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garcia A, Shankar H, Murugappan S, Kim S, Kunapuli SP. Regulation and functional consequences of ADP receptor-mediated ERK2 activation in platelets. Biochem. J. 2007;404:299–308. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gao X, et al. PI3K/Akt signaling requires spatial compartmentalization in plasma membrane microdomains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:14509–14514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019386108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bodin S, Tronchere H, Payrastre B. Lipid rafts are critical membrane domains in blood platelet activation processes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1610:247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(03)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Philipose S, et al. The prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 is expressed by human platelets and potently inhibits platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30:2416–2423. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pasterk L, et al. Oxidized plasma albumin promotes platelet-endothelial crosstalk and endothelial tissue factor expression. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22104. doi: 10.1038/srep22104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schuligoi R, et al. PGD2 metabolism in plasma: kinetics and relationship with bioactivity on DP1 and CRTH2 receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;74:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.