Abstract

Hospitalizations for advanced liver disease are costly and associated with significant mortality. This population-based study aimed to evaluate factors associated with in-hospital mortality and resource use for the management of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis.

Mortality records and resource utilization for 52,027 patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and/or complications of portal hypertension (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or hepatorenal syndrome) were extracted from a nationally representative sample of Thai inpatients covered by Universal Coverage Scheme during 2009 to 2013.

The rate of dying in the hospital increased steadily by 12% from 9.6% in 2009 to 10.8% in 2013 (P < .001). Complications of portal hypertension were independently associated with increased in-hospital mortality except for ascites. The highest independent risk for hospital death was seen with hepatorenal syndrome (odds ratio [OR], 5.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.38–5.79). Mortality rate remained high in patients with infection, particularly septicemia (OR, 4.26; 95% CI, 4.0–4.54) and pneumonia (OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 2.18–2.73). Receiving upper endoscopy (OR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.27–0.32) and paracentesis (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.87–1.00) were associated with improved patient survival. The inflation-adjusted national annual costs (P = .06) and total hospital days (P = .07) for cirrhosis showed a trend toward increasing during the 5-year period. Renal dysfunction, infection, and sequelae of portal hypertension except for ascites were independently associated with increased resource utilization.

Renal dysfunction, infection, and portal hypertension-related complications are the main factors affecting in-hospital mortality and resource utilization for hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. The early intervention for modifiable factors is an important step toward improving hospital outcomes.

Keywords: cirrhosis, mortality, portal hypertension, resource utilization

1. Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is a major cause of health burden worldwide. According to the Global Burden of Disease study, liver cirrhosis caused 1.2% of global disability-adjusted life years and 2% of all deaths worldwide in 2010.[1,2] Globally, the age-standardized cirrhosis mortality rate decreased by 22% over the last 3 decades. This was mostly driven by reducing cirrhosis death rates in the United State and countries in Western Europe.[1–4] Mortality rates among countries, however, were variable and mainly driven by the prevalence of risk factors for the disease including the quantity and pattern of alcohol intake and viral hepatitis.[4,5] Notably, mortality risk increases sharply once cirrhosis patients experience decompensation.[6,7] Decompensation of cirrhosis may present acutely with ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, acute renal failure, and bacterial infections that lead to hospitalization. Without proper management of the complications and subsequent liver transplantation, patients with decompensated cirrhosis have a 5-year survival rate of less than 50%.[6] However, careful management can mitigate this adverse outcome.[8–11]

Because of the poor outcomes associated with hospitalization for liver cirrhosis and its related diseases, identification of prognostic indicators of in-hospital mortality may help to determine which patients require intensive care treatment. In a systematic review of 118 prognostic studies of cirrhosis, the variable that was found to be the most common independent predictor of death was the Child–Pugh score followed by all its components.[12] However, the reported prognostic variables from these studies were identified to forecast long-term survival and the requirement of liver transplantation but were not designed for predicting in-hospital death outcome. Thus, identifying the robust predictors of death during hospitalization is challenging. Furthermore, the management of hospitalized patients with liver cirrhosis is associated with a substantial economic burden.[13] Nonetheless, the data regarding factors that are associated with high utilization of healthcare resource for the management of cirrhosis is largely undescribed yet, and is important to stakeholders involved in the delivery of healthcare. Herein, we analyzed a large, nationally representative sample of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis to identify prognostic factors affecting in-hospital mortality and resource utilization. In addition, this population-based study aimed to determine whether there has been a change in hospital mortality and healthcare resource use for hospitalization of cirrhosis and its related diseases during the recent period.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The data for this study came from discharges in the nationwide sample of inpatients covered by the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS), which comprises 76% of all admissions from more than 1000 community and academic centers spread across 77 provinces in Thailand. Each discharge record has a unique identifier, demographic data, primary diagnosis, secondary diagnoses, in-hospital procedures, discharge status, total hospital charges, the length of stay (LOS), and hospital characteristics (region, bed size, and teaching status). External audits of discharge records are performed periodically by the National Health Security Office (NHSO) to ensure the quality of the data.

The NHSO database contains 28,294,685 individual discharge records from 2009 through 2013. By using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnostic and procedural codes, 52,027 cases with codes indicating cirrhosis (K74.0-K74.6) as primary or any secondary diagnosis were identified.

2.2. Variables

We collected information from all discharges by using ICD-10-CM codes for the following diagnoses: ascites (R18), hepatic encephalopathy (K72), variceal bleeding (I85.0, I98.2, and I98.3), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) (K65.0 and K65.2), hepatorenal syndrome (K76.7), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (C22.0). The diagnostic codes also were used to identify patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (B18.0 and B18.1), hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (B18.2), alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) (K70.0-K70.4 and K70.9), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (K76.0 and K75.8), autoimmune hepatitis (K75.4), biliary cirrhosis (K74.3-K74.5 and K80.3), Wilson disease (E83.0), hemochromatosis (E83.1), toxic liver disease (K71.7 and K71.8), and cardiac cirrhosis (K76.1). Patients were categorized into the following etiological groups: alcohol, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, autoimmune hepatitis, biliary cirrhosis, NAFLD, cryptogenic, and “others.” Patients were classified as having cryptogenic cirrhosis when the etiology was unknown. Patients were grouped as “others” when a specific cause was identified, but the number was low such as for patients with cirrhosis due to Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, toxic liver disease, and cardiac cirrhosis.

Comorbid conditions for risk prediction of hospital outcomes were obtained and included septicemia (A40–A41), pneumonia (J12–J18), urinary tract infection (N39), acute renal failure (N17), cerebrovascular disease (I60–I69), ischemic heart disease (I20–I25), diabetes mellitus (E10–E11), chronic lower respiratory disease (J40–J47), chronic kidney disease (N18–N19), malignant neoplasm excluding HCC (C00–C97), and concurrent human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) with or without acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) (B20–B24 and Z21). Diagnostic and therapeutic measures were identified by using the following procedural codes: upper endoscopy (4513 and 4233), abdominal paracentesis (5491), and blood transfusion (9904).

In Thailand, government hospitals, which are operated by the Ministry of Public Health, are classified into 3 levels. Primary hospital is a community hospital with a capacity of 10 to 200 beds being at the districts. Secondary hospital is a general hospital with a capacity of 200 to 500 beds located in province capitals or major communities. Tertiary hospital is a regional hospital with a capacity of at least 500 beds placed in provincial centers and has a comprehensive set of specialists on staff. A university hospital is an institution affiliated with a university that provides medical education and training, in addition to delivering health care to patients. The 4-census region of Thailand used in the analysis included the Central, North, Northeast, and South.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University approved the research protocol before beginning this research. A data use agreement was in place with the Gastroenterological Association of Thailand for the use of the NHSO data. The SPSS software package version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses.

The total number of patients hospitalized for liver cirrhosis by calendar year and Thai census population covered by the UCS estimate for that year were used to calculate the annual incidence of patients hospitalized for cirrhosis. Trend testing for incidence rates and aggregate measures of total charges and days of hospitalization were analyzed using Poisson and linear regression, respectively, with time as the independent variable. Mortality was expressed as the in-hospital case-fatality rate, which was defined as the proportion of admissions of patients with cirrhosis that resulted in death. Factors associated with in-hospital deaths were ascertained using logistic regression analysis while accounting for potential confounders. Multivariate linear regression models with accounting for the confounding variables were used to determine factors influencing hospital charges and LOS. The following covariates were used in these models: demographic information (age, gender, and calendar year), clinical characteristics of patients (etiology of cirrhosis, variceal bleeding, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, SBP, hepatorenal syndrome, HCC, septicemia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, acute renal failure, and comorbid conditions), and hospital characteristics (hospital level, geographic location, and teaching status). The models were constructed for both hospital charges and LOS after logarithmic transformation of the skewed data. The estimated coefficients from the models were exponentiated to quantify how strongly the presence or absence of each variable associated with charges and LOS as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). For the cost analysis, money values in Thai baht were converted into United States dollar (USD) using exchange rate of ∼33 Thai baht per USD.[14] To adjust for inflation, the Thailand Consumer Price Index for 2013 was used for the analysis of the federal annual total hospital charges.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis

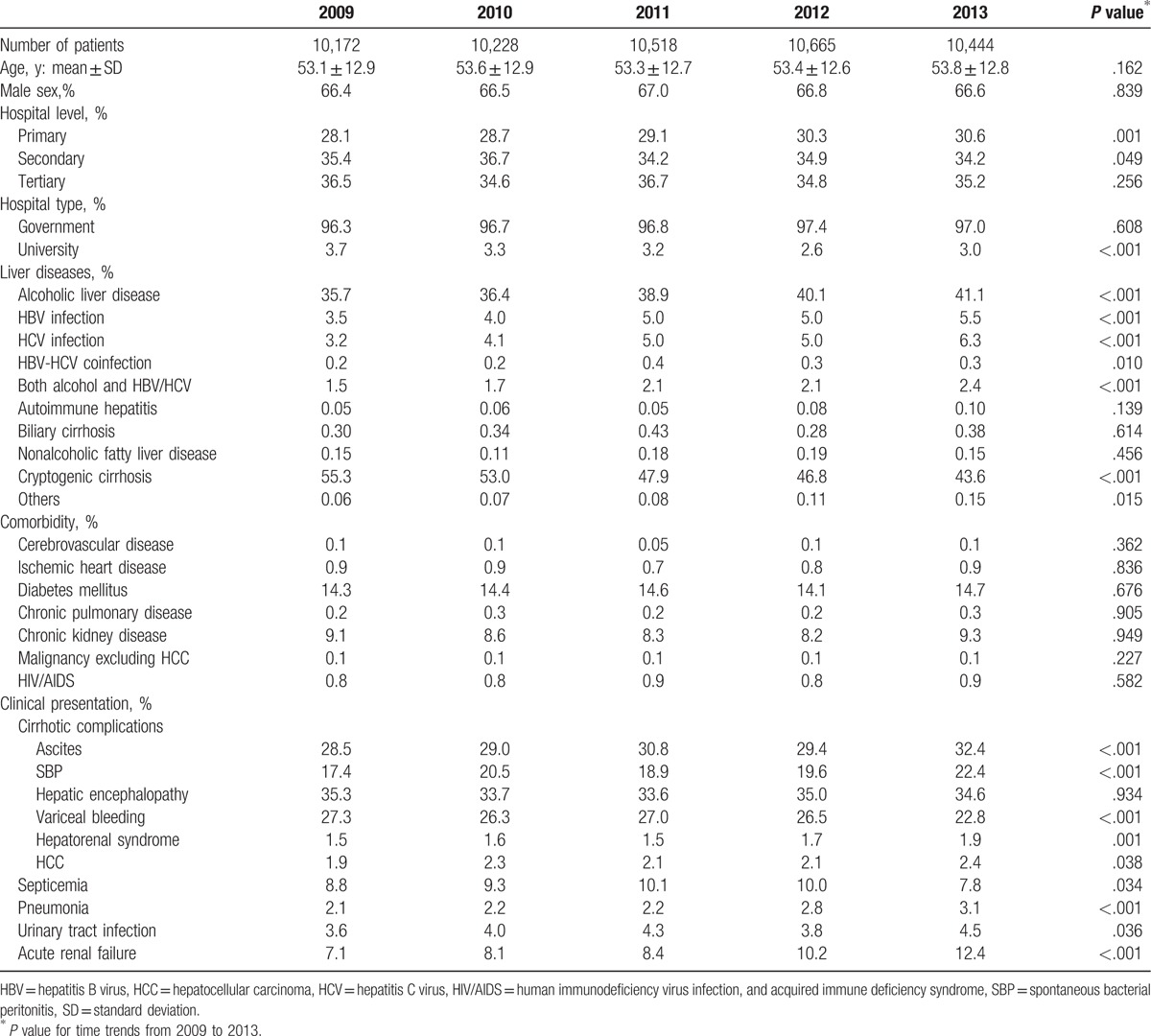

Clinical features of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. The mean age of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis was 53.4 ± 12.8 years, and this did not vary significantly during the 5-year period. Almost two-thirds of the patient cohort was male. ALD without viral hepatitis infection accounted for 40% of hospitalized patients with a significant increase in the prevalence over the 5-year period (Table 1). While HBV or HCV-related cirrhosis represented a relatively small (∼9%) but increasing proportion of patients with virus-related cirrhosis. The prevalence of patients with HBV infection alone rose from 3.5% to 5.5% during the 5-year period, whereas the prevalence of patients with HCV infection alone increased steadily from 3.2% to 6.3%. The prevalence of patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis decreased progressively from 55.3% to 43.6% during the same period. The overall prevalence of NAFLD related-cirrhosis was 0.16% without significant variation over time. Concomitant diabetes mellitus was present in 14.4% of the entire population, and the prevalence did not vary significantly with time. Specifically, the prevalence of diabetes in patients with NAFLD and those with cryptogenic cirrhosis were 23.5% and 9.5%, respectively, that were significantly higher than the overall prevalence of 4.9% observed in patients with other etiologies of cirrhosis.

Table 1.

Demographic and characteristics of patients hospitalized with cirrhosis between 2009 and 2013.

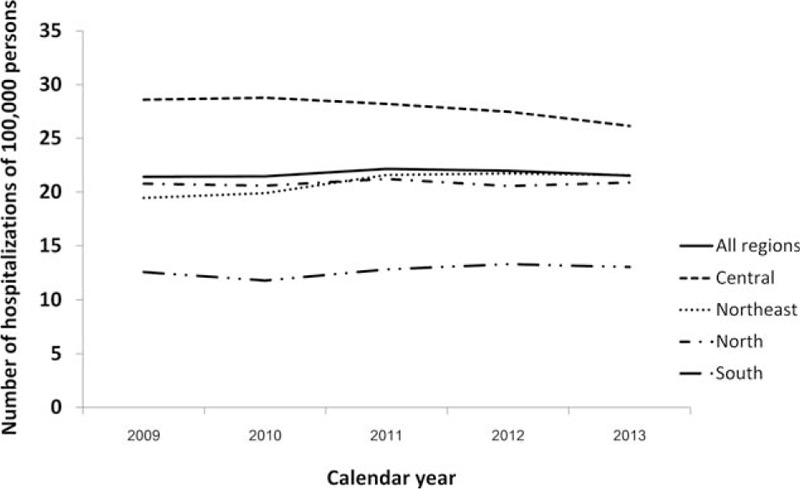

The annual incidence of hospitalization for cirrhosis was stable over time (Fig. 1), ranging from 21.4 per 100,000 in 2009 to 21.5 per 100,000 in 2013. Stratified by geographic region, there was no significant difference in the annual rate of admission for cirrhosis in the North and the South from 2009 through 2013. In contrast, the incidence rate of hospitalization per year significantly showed an average 2.2% decrease in the Central and an average 2.6% increase in the Northeast during the same period. Though no significant changes in the number of admissions among each hospital level existed, the proportion of patients who were admitted to primary hospital increased significantly over the time.

Figure 1.

Annual incidence of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis in the nationwide inpatient sample from 2009 to 2013. Rates of patients hospitalized with cirrhosis are illustrated for the Thai census population and stratified by geographic region.

For clinical manifestations of portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy was present in nearly one-third of all admissions, without significant variation over the 5-year period. Although 30% had a diagnosis of ascites, only two-thirds of these admissions were complicated with SBP. There were significant increasing trends in hospitalization for both complications from 2009 to 2013. The overall prevalence of hepatorenal syndrome and HCC was 1.6% and 2.2%, respectively, with significant increasing trends over time. In contrast, annual hospitalization rates for variceal bleeding significantly decreased from 27.3% to 22.8% during the same period.

3.2. In-hospital mortality

The percentage of cirrhosis patients who died during admission increased steadily from 9.6% in 2009 to 10.8% in 2013 (P < .001). There was a 3% relative increase in the adjusted in-hospital case-fatality rate per year. Among cirrhosis patients with hepatorenal syndrome, the case-fatality rate was 36.9%, without significant variation over the 5-year period.

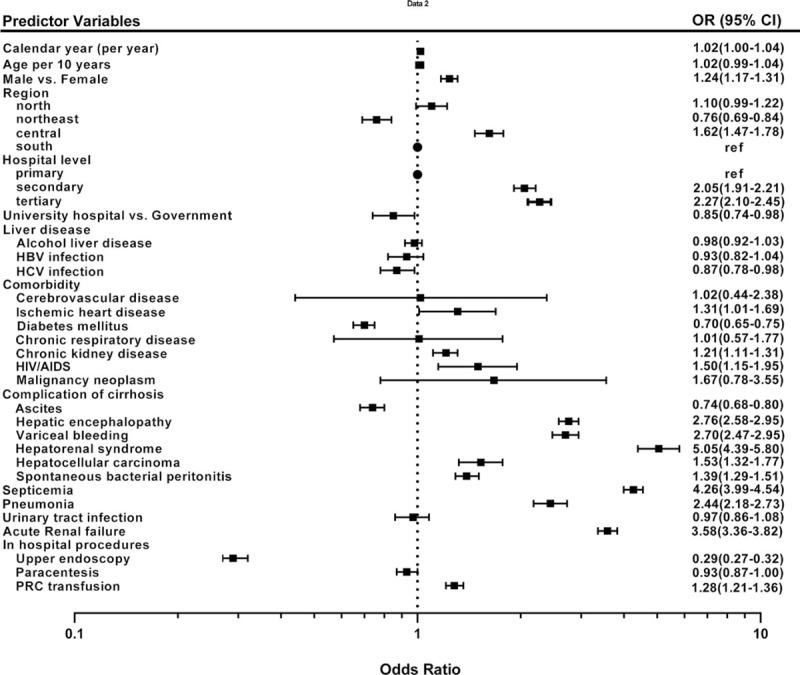

Figure 2 shows patient and clinical characteristics that were associated with in-hospital death after adjustment for potential confounders. Male sex was associated with higher mortality compared with female sex. There were regional variations in mortality, with the Central experiencing 62% higher death rates as compared with the South (Fig. 2). Secondary hospitals and tertiary hospitals were associated with higher mortality compared with primary hospitals, whereas university hospitals were associated with lower mortality compared with government hospitals.

Figure 2.

Multivariate analysis of factors affecting in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis between 1999 and 2013. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) of in-hospital mortality for demographic and clinical variables are graphically presented (▪) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Reference categories are shown (●). Each OR is adjusted simultaneously for all other variables and is numerically shown to the right.

In multivariate analysis, each complication of portal hypertension was independently associated with increased mortality except for ascites, which showed an inverse relationship. The hepatorenal syndrome and acute renal failure were the most important independent predictors of in-hospital death. Furthermore, mortality rates remained high in those complicated with bacterial infection, particularly septicaemia, and pneumonia. Extrahepatic comorbidities also were associated with in-hospital death except for diabetes, which showed a modest inverse relationship.

3.3. Healthcare resource utilization

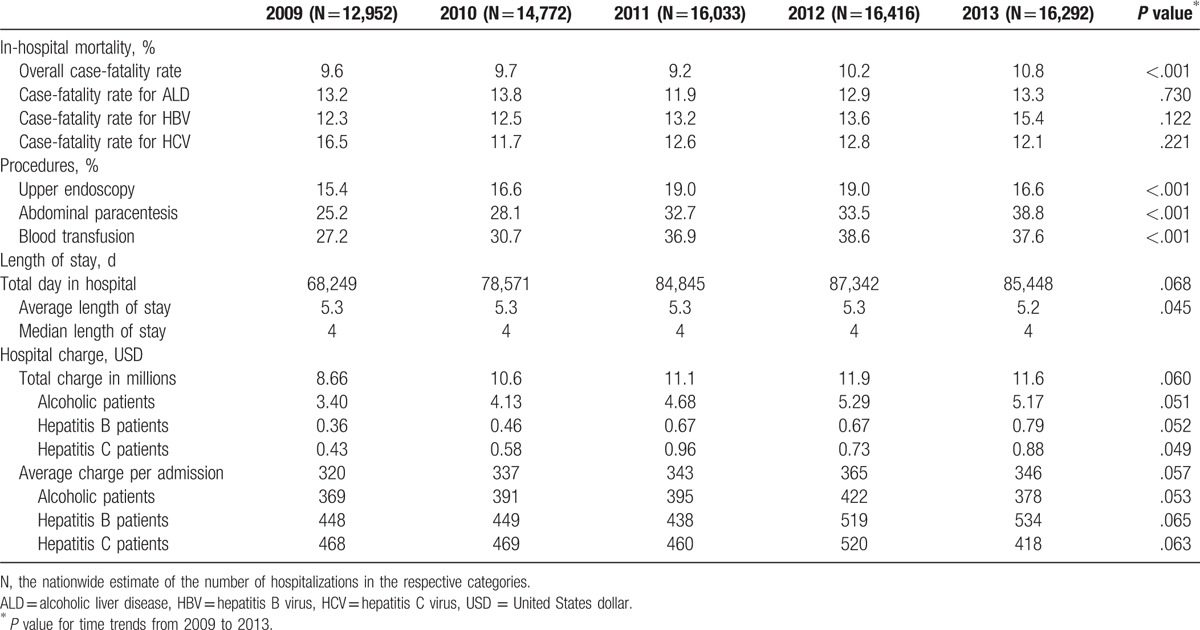

During hospital admission, 17.4% and 32% of patients underwent upper endoscopy and abdominal paracentesis, respectively, and there were significant increasing trends over the 5-year period. The national estimate of a total number of hospital days increased from 68,249 days in 2009 to 85,448 days in 2013 even with a small but statistically significant decreasing trend in average LOS during the 5-year period (P = .045). However, the median LOS remained stable at 4 days.

Between 2009 and 2013, the federal annual total hospital charges for admissions with cirrhosis showed a trend toward increasing from 8.66 million to 11.6 million USD after adjustment for inflation. The average charges per admission rose from 320 to 346 USD during the study period but did not reach statistical significance (Table 2).

Table 2.

In-hospital mortality and resource use for hospitalized patients with cirrhosis between 2009 and 2013.

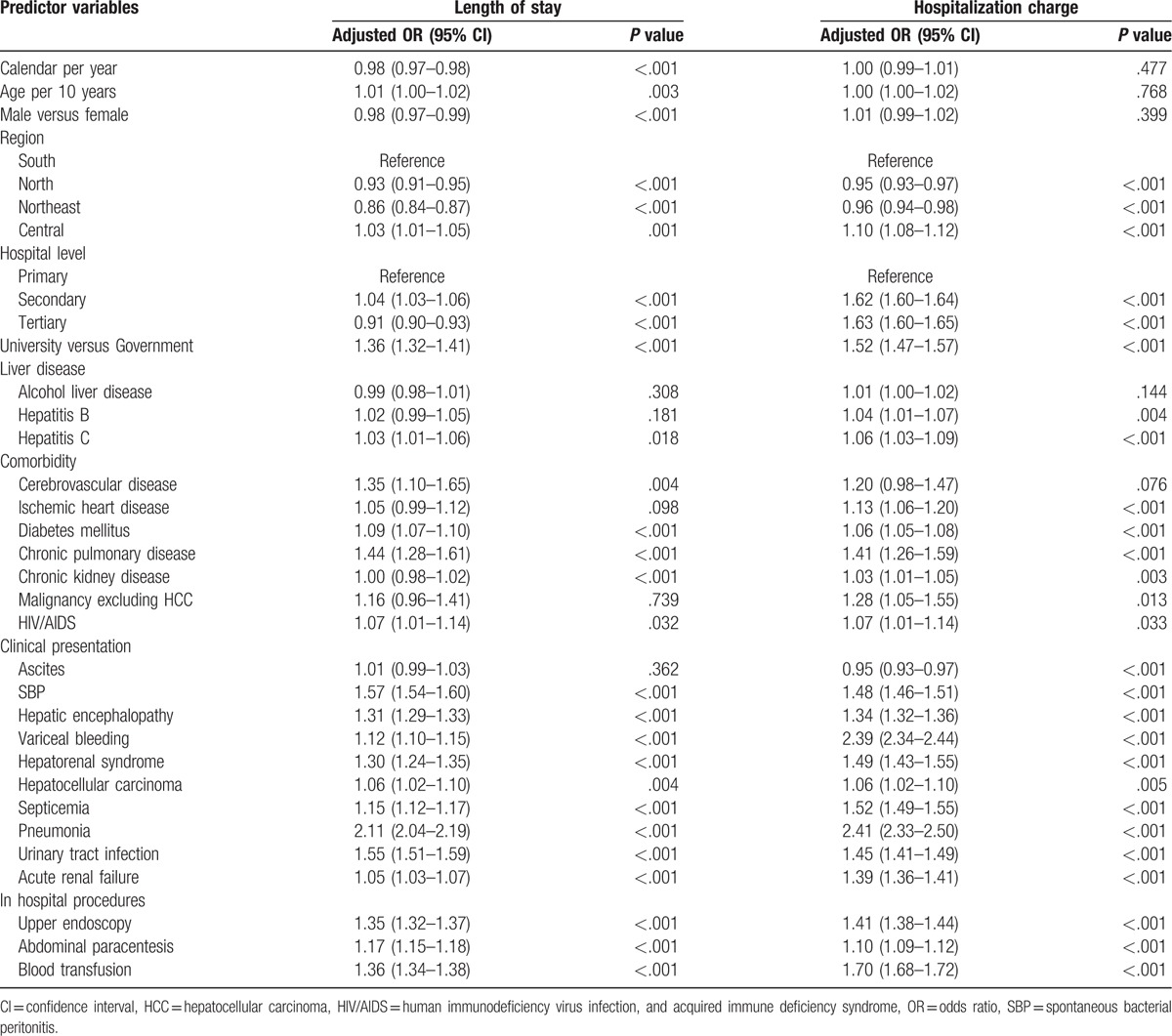

Table 3 presents the factors associated with both hospital charges per admission and LOS after simultaneous adjustment for all variables. While improvement in LOS for cirrhosis occurred each passing year in men, LOS extended with increasing age. On average, charges and LOS were higher in the Central compared with the other regions. Cirrhosis patients admitted to university hospitals had charges and LOS greater than those hospitalized in government hospitals. Liver disease caused by HCV infection was associated with modest but significant increases in both hospital charges and LOS. Among comorbid conditions, chronic pulmonary disease prominently had the impact on resource use with increasing LOS by 44% and hospital charges by 41%. Each complication of portal hypertension was independently associated with higher charges and LOS except for ascites, which showed an inverse relationship with expenditures. As expected, acute renal dysfunction and infection, mainly pneumonia, had an intense impact on charges and LOS. Having undergone an endoscopic procedure increased LOS by 35% and hospital charges by 41%.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors affecting length of stay and hospitalization charges in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis.

4. Discussion

This population-based study demonstrated that renal dysfunction, infection, and portal hypertension-related complications are the main factors affecting in-hospital mortality and resource utilization for hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. We further described increasing trends in in-hospital mortality of patients with cirrhosis, which are mainly attributable to the changes in incidence of decompensating events resulting in increased utilization of healthcare resource.

In this nationwide study, we found that ALD is the leading cause of liver cirrhosis with overall prevalence estimated at 40% of hospitalized patients and a rising in the rates over the recent 5 years. This corresponds well to the increasing levels of alcohol consumption in Thailand during the last decade reported by the World Health Organization.[15] These findings indicate that disorders related to alcohol use continue to be a major health problem in our country, and it underscores the need for implementation of public behavioral modification programs and educational interventions for alcohol cessation. We also observed an increasing proportion of patients with viral hepatitis-related cirrhosis. Although the incidence rates of HBV and HCV infection have declined over the past 20 years according to the national examinations survey during 1988 to 2009 in Thailand,[16] the incidence of individuals with HBV or HCV-infected cirrhosis is expected to increase because of the long latency of viral infection. Antiviral treatment in the early disease course has been reported to be a cost-effective strategy that reduces progression to cirrhosis.[17–19] However, only a minority of Thai patients with chronic HBV or HCV infection receives treatment despite the availability of effective therapies covered by the national health scheme. The profound health loss attributable to viral hepatitis and the availability of effective therapies suggests an opportunity to reduce rates of hospitalization and overall inpatient expenditure.[5]

Despite the increasing recognition of NAFLD as a major public health burden worldwide, the prevalence of NAFLD related-cirrhosis was somewhat lower in our study compared with the previously reported estimates,[20,21] and this is likely related to our case ascertainment. In this study, the diagnosis of NAFLD was defined based on ICD-10 codes, which may be prone to misclassification. Given a significant proportion of our patients with NAFLD risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, some of these individuals may have progressed from nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to cirrhosis given diabetes is a major contributor to perpetual chronic injury leading to eventual NASH, cirrhosis, and HCC.[22,23] Supporting this view, patients with NAFLD or cryptogenic cirrhosis had a higher incidence of diabetes than those with cirrhosis of other known etiologies, suggests that a proportion of cryptogenic cirrhosis might be a burnt-out NASH. Notably, the analysis showed that a substantial number of cases remained unknown etiology of cirrhosis. It is, however, realized that most of these patients might have occult alcohol consumption, unrecognized viral hepatitis, and silent autoimmune hepatitis.[21] This data underlines a common problem, which is unrecognized by physicians. Hence, education on diagnosis and treatment of this condition among physicians caring for cirrhosis should be intensified.

Mortality from liver cirrhosis has sharply declined in most countries around the world in the last few decades.[4,24–26] Conversely, the persisting upward trends up to the recent calendar period were observed in Thailand. Our analysis demonstrated the absolute rate of dying in the hospital increased steadily by 12% from 9.6% in 2009 to 10.8% in 2013. This observation coincides with the report on the increasing in cirrhosis mortality in developing countries, particularly in Central Asia and Africa.[4] The consistent increase in mortality rate for Thai cirrhosis patients requiring hospitalization, year to year, has been not related to the aging of the patient cohort. The average age at hospitalization for advanced liver disease has remained stable at 53 years. Indeed, the pattern in death from cirrhosis is attributable to changes in several cirrhosis-related conditions, sex, geographic region, and hospital level. In particular, the variations in mortality trends over time are primarily driven by changes in clinical manifestations of portal hypertension. In agreement with the prognostic stages of cirrhosis,[27] our analysis showed that the risk of death during hospitalization was significantly higher in patients with variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome, even when adjusted for other potential confounders. This finding underlies the prognostic role of major clinical manifestations of portal hypertension, and each critical event has a different strength of association with the patient outcome. In contrast to previous studies,[27,28] we found that patients hospitalized with uncomplicated ascites had significantly a better survival than those without this clinical event. However, prognosis is affected so adversely, after the occurrence of ascitic fluid infection. Although the reason for a better prognosis of patients hospitalized with ascites is unknown, it is possible that the recognition of ascites leads to initiate early treatment for the improvement in nutritional status, which have the potential benefit on clinical outcomes and prevent other cirrhosis-related complications.[7] Nonetheless, we were unable to properly assess the role of nutritional interventions on mortality risk in our database.

Cirrhosis is considered an immunocompromised state that leads to a variety of infections, which may result in organ dysfunction and death.[29] Our results are in line with earlier studies showing that bacterial infection particularly septicemia, pneumonia, and SBP were robust predictors of death for hospitalized patients with cirrhosis.[29–32] The negative clinical impact of infections in patients with cirrhosis can be alleviated by prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy after the diagnosis of bacterial infection.[33] In addition, earlier diagnosis is needed, whether by surrogate markers or new microbiologic techniques for the identification of the causative organisms, to allow earlier treatment.[34] Renal failure is a frequent complication of advanced cirrhosis due to several causes, and is associated with a high mortality.[31,35] In our analysis, the high in-hospital mortality was significantly associated with the development of acute renal failure. In particular, hepatorenal syndrome appears to be the strongest predictor of death for hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. This life-threatening condition requires a high index of diagnostic suspicion and aggressive management to improve the patient outcome.[36] Therefore, renal dysfunction and infection in cirrhosis, irrespective of the presence of other complications of portal hypertension, could be prognostic factors, demarcating additional prognostic stages to those proposed by D’Amico et al.[27] However, prospective studies are needed to verify this prognostic importance.

The prognostic value of diabetes in cirrhosis has been examined in a limited number of studies on selected patients.[23] Most studies found that diabetes was associated with a lower survival.[37–39] In contrast to earlier reports,[37–39] our analysis revealed that cirrhotic patients with concurrent diabetes had a modest 30% lower in-hospital mortality risk than those without diabetes. Possible explanations for this discrepancy may reside in differences in the hospitalization setting and the study design. The significance of this finding is unclear, and it can be speculated that the result is erroneous according to the analysis of administrative database. However, our finding is consistent with the result from a large nationwide study of cirrhotic patients hospitalized for major complications of portal hypertension in the United States.[30] These data suggest that patients with diabetes may have a more benign hospital course. It is unclear whether this survival advantage arises from a milder disease on admission or the diagnosis of diabetes being as a surrogate for some treatments that can modify the hospital outcomes.

A striking finding of this study is the association between the optimum cirrhosis care and improved survival. Kanwal et al[40] showed a reduction in 12-month mortality for cirrhosis patients who received the recommended care and suggested using several interventions including paracentesis during admissions as a set of quality indicators for the cirrhosis care. Our results confirm that paracentesis any time during the hospitalization was associated with reduced mortality in patients admitted for symptoms from ascites.[41,42] This finding emphasizes a clinical strategy to implement routine diagnostic paracentesis at the time of hospitalization in cirrhosis patients presenting with ascites. Furthermore, receiving upper endoscopy during admission was associated with a decrease in mortality of those with gastrointestinal bleeding. In contrast to both cirrhosis-specific interventions, we found blood transfusion during hospitalization associated with a higher mortality rate, which is probably related to its use for severe and active bleeding patient. Interestingly, admission to university hospitals was associated with a lower mortality rate compared with hospitalization to government hospitals. The improvement in cirrhosis survival among patients admitted to university hospitals may be owing to better cirrhosis-specific care extending beyond general improvements in hospital care. A previous study demonstrated that cirrhosis patients cared by a gastroenterologist were more likely to achieve the quality indicators.[40] This data accentuates that mortality benefits can be accomplished by directly modifying physician behavior to perform the best practice.[42]

A better understanding of determinants of increased resource utilization for hospitalization of cirrhosis might provide an efficient resource allocation for the management of cirrhosis. In this study, LOS and hospital charges were used as surrogate markers for resource utilization. Our results showed that hospitalization with clinical events of portal hypertension, infection, acute renal failure, and comorbid illness is associated with excessive hospital resource utilization. As expected, treatment in high-resource-intensity medical centers and performing procedures was associated with increased resource utilization. The analyses also highlight significant geographic variation in resource utilization. Patients from the Central had higher odds of being high resource utilization cases, and those admitted to the North and the Northeast had significantly lower odds of being high resource utilization cases compared with patients from the South. Our findings would further support that there are clinical predictors of financial risk that may facilitate implementation of risk adjustment for payers.

The main advantage of using the NHSO is that the collection of data within the NHSO is not driven by specific research questions and consequently, is not subject to the ascertainment biases as may be present in hospital-based series. A large number of patients allows for analyses of clinical outcomes accounting for multiple confounders while maintaining precision. However, the results should be interpreted in the context of the limitations associated with the use of administrative data, which is based on medical record coding. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that our contradictory findings on the mortality risk in individuals with diabetes/ascites might be related to the reliability of the NHSO data. These results should be subjected to further verification. In addition, the NHSO database does not capture many variables for estimating disease severity (e.g., model for end-stage liver disease and Child–Pugh scores). However, there is a reason to believe the severity of hepatic dysfunction among our inpatients increased over time as increasing trends in the occurrence of ascites and renal dysfunction. These parameters are the basis of both prognostic scoring systems, and it may designate the increasing admission rates of patients with advanced liver disease. Notably, our findings may have limited generalizability, as they are derived from a single country. It is likely that the etiologies of cirrhosis vary among different patient populations. Nonetheless, previous studies lend validity to our findings by identifying similar prognostic factors for in-hospital mortality and resource utilization in other ethnic populations.[27–32]

In conclusion, we demonstrated that renal dysfunction is the most robust predictor for in-hospital mortality, followed by bacterial infection and portal hypertension-related complications. Most of the identified factors reflect a state of liver decompensation that did not only have a significant impact on short-term survival but also affected substantial resource use. Thus, in cirrhosis patients hospitalized with acute renal dysfunction, bacterial infection particularly septicemia, pneumonia and SBP, as well as clinical features of portal hypertension, the therapy should be more aggressive, aiming to improve hospital outcomes. This data clearly represents a challenge for our healthcare services and will have substantial implications for the future trends in mortality and economic burdens from this disease.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALD = alcohol-related liver disease, CI = confidence interval, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV = hepatitis C virus, HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome, ICD-10-CM = International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Clinical Modification, LOS = length of stay, NAFLD = nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, NASH = nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, NHSO = National Health Security Office, OR = odds ratio, SBP = spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, UCS = Universal Coverage Scheme, USD = United States dollar.

PC contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting the manuscript, and gave final approval of submitted version of manuscript. NS, KK, KP, WP, WC, TT, KP contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data, and reviewing the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Gastroenterological Association of Thailand.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2163–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mokdad AA, Lopez AD, Shahraz S, et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med 2014;12:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2016;388:1081–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Grewal P, Martin P. Care of the cirrhotic patient. Clin Liver Dis 2009;13:331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nishikawa H, Osaki Y. Liver cirrhosis: evaluation, nutritional status, and prognosis. Mediators Inflamm 2015;2015:872152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Carbonell N, Pauwels A, Serfaty L, et al. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology 2004;40:652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Weinstein MP, Iannini PB, Stratton CW, et al. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A review of 28 cases with emphasis on improved survival and factors influencing prognosis. Am J Med 1978;64:592–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chalasani N, Kahi C, Francois F, et al. Improved patient survival after acute variceal bleeding: a multicenter, cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:653–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fernandez J, Navasa M, Planas R, et al. Primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis delays hepatorenal syndrome and improves survival in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2007;133:818–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Neff GW1, Kemmer N, Duncan C, et al. Update on the management of cirrhosis—focus on cost-effective preventative strategies. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2013;5:143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bank of Thailand. Foreign Exchange Rates. Available at: http://www.bot.or.th/english/statistics/financialmarkets/exchangerate/_layouts/Application/ExchangeRate/ExchangeRateAgo.aspx; 2013. Accessed September 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [15].World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chimparlee N, Oota S, Phikulsod S, et al. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus in Thai blood donors. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2011;42:609–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tantai N, Chaikledkaew U, Tanwandee T, et al. A cost-utility analysis of drug treatments in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B in Thailand. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dan YY, Wong JB, Hamid SS, et al. Consensus cost-effectiveness model for treatment of chronic hepatitis B in Asia Pacific countries. Hepatol Int 2014;8:382–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Obach D, Yazdanpanah Y, Esmat G, et al. How to optimize hepatitis C virus treatment impact on life years saved in resource-constrained countries. Hepatology 2015;62:31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF). AISF position paper on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): updates and future directions. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:471–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rinaldi L, Nascimbeni F, Giordano M, et al. Clinical features and natural history of cryptogenic cirrhosis compared to hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:1458–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Piscaglia F, Svegliati-Baroni G, Barchetti A, et al. HCC-NAFLD Italian Study Group. Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a multicenter prospective study. Hepatology 2016;63:827–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Loria P, Lonardo A, Anania F. Liver and diabetes. A vicious circle. Hepatol Res 2013;43:51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bosetti C, Levi F, Lucchini F, et al. Worldwide mortality from cirrhosis: an update to 2002. J Hepatol 2007;469:827–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zatoński WA, Sulkowska U, Mańczuk M, et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in Europe, with special attention to Central and Eastern Europe. Eur Addict Res 2010;16:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schmidt ML, Barritt AS, Orman ES, et al. Decreasing mortality among patients hospitalized with cirrhosis in the United States from 2002 through 2010. Gastroenterology 2015;148:967–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].D’Amico G, Pasta L, Morabito A, et al. Competing risks and prognostic stages of cirrhosis: a 25-year inception cohort study of 494 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:1180–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zipprich A, Garcia-Tsao G, Rogowsky S, et al. Prognostic indicators of survival in patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Liv Int 2012;32:1407–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Arvaniti V, D’Amico G, Fede G, et al. Infections in patients with cirrhosis increase mortality four-fold and should be used in determining prognosis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1246–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nguyen GC, Segev DL, Thuluvath PJ. Nationwide increase in hospitalizations and hepatitis C among inpatients with cirrhosis and sequelae of portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:1092–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Renal dysfunction is the most important independent predictor of mortality in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:260–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Vergara M, Clèries M, Vela E, et al. Hospital mortality over time in patients with specific complications of cirrhosis. Liver Int 2013;33:828–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2010;53:397–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Enomoto H, Inoue S, Matsuhisa A, et al. Development of a new in situ hybridization method for the detection of global bacterial DNA to provide early evidence of a bacterial infection in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Hepatol 2012;56:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fede G, D’Amico G, Arvaniti V, et al. Renal failure and cirrhosis: a systematic review of mortality and prognosis. J Hepatol 2012;56:810–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Angeli P, Sanyal A, Moller S, et al. International Club of Ascites. Current limits and future challenges in the management of renal dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis: report from the International Club of Ascites. Liver Int 2013;33:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Stepanova M, Rafiq N, Younossi ZM. Components of metabolic syndrome are independent predictors of mortality in patients with chronic liver disease: a population-based study. Gut 2010;59:1410–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Quintana JOJ, Garcıa-Compean D, Gonzalez JAG, et al. The impact of diabetes mellitus in mortality of patients with compensated liver cirrhosis—a prospective study. Ann Hepatol 2011;10:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Elkrief L, Chouinard P, Bendersky N, et al. Diabetes mellitus is an independent prognostic factor for major liver related outcomes in patients with cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2014;60:823–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Buchanan P, et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology 2012;143:70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Orman ES, Hayashi PH, Bataller R, et al. Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kim JJ, Tsukamoto MM, Mathur AK, et al. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1436–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]