Abstract

Up-regulation of proapoptotic genes has been reported in heart failure and myocardial infarction. To determine whether caspase genes can affect cardiac function, a transgenic mouse was generated. Cardiac tissue-specific overexpression of the proapoptotic gene Caspase3 was induced by using the rat promoter of α-myosin heavy chain, a model that may represent a unique tool for investigating new molecules and antiapoptotic therapeutic strategies. Cardiac-specific Caspase3 expression induced transient depression of cardiac function and abnormal nuclear and myofibrillar ultrastructural damage. When subjected to myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury, Caspase3 transgenic mice showed increased infarct size and a pronounced susceptibility to die. In this report, we document an unexpected property of the proapoptotic gene caspase3 on cardiac contractility. Despite inducing ultrastructural damage, Caspase3 does not trigger a full apoptotic response in the cardiomyocyte. We also implicate Caspase3 in determining myocardial infarct size after ischemia–reperfusion injury, because its cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression increases infarct size.

Programmed cell death (apoptosis) has been implicated in normal biological processes and in the pathogenesis of several diseases in humans (1). The characterization of genes involved in apoptosis has been pursued intensively and has led to the identification of two major classes of genes, one represented by the Bcl2 family and the other by the Caspase family. Caspases are a family of proteases that cleave their target substrates at specific peptide sequences (2). During apoptosis, activation of caspases, variably induced by nuclear, metabolic, or externally activated stimuli, takes place in a cascade fashion, leading to nuclear engulfment and cell death (2).

Recent findings suggest a role of apoptosis in heart failure. Apoptotic cardiomyocyte nuclei have been described in pressure overload and pacing-induced heart failure in animals (3–5), which are associated with increased Bax and decreased Bcl-2 protein expression (5). Cardiomyocyte apoptosis also can be detected in myocardial tissue of patients with heart failure resulting from idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (6) and other cardiac disorders (7). Caspase3 expression is increased in association with heart failure and apoptosis in experimental animals (8), is found in its activated form in the myocardium of end-stage heart failure patients (9), and is overexpressed in the myocardium of patients with right ventricular dysplasia, a disease associated with myocardial apoptosis, progressive cell loss, and sudden death (10), indicating relevance of caspase3 to human heart disease.

Apoptosis also has been implicated in determining infarct size after ischemia–reperfusion in different organs (11). In particular, blockade of caspase activation with a peptide inhibitor was reported to decrease infarct size after coronary artery ligation in rats (12). A cause–effect relationship between caspase3 (also called cpp32 or yama) and cardiac function as well as the role of caspase3 in determining infarct size has not been established yet. In an attempt to answer this question, we generated transgenic mice overexpressing Caspase3 in the heart. This experimental model may represent a unique tool for investigating new molecules and antiapoptotic therapeutic strategies. Thus, heart-targeted overexpression of caspase3 in mice was characterized at both functional and molecular levels under basal conditions and after ischemia–reperfusion.

Materials and Methods

Generation and Genotyping of Transgenic Mice.

Human Caspase3 cDNA (provided to us by E. Alnemry, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia) was amplified by PCR, and a SalI site was created at the flanking ends. The α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) promoter (gift from J. Robbins, Univ. of Cincinnati) was ligated with simian virus 40 poly(A)/INS that was obtained from Εμ vector (gift from J. Adams, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Melbourne, Australia) so that a unique SalI-cloning site was generated. Caspase3, previously sequenced for possible PCR-generated mutations, was cloned in the SalI site. Thereafter, the fragment containing α-MHC, Caspase3, and simian virus 40 was excised by NotI digestion, purified, and used for injection according to conventional techniques.

Mouse genotyping was done by digesting the genomic DNA with EcoRI. Membranes were hybridized with the respective probes.

Protein Analysis of the Transgenic Phenotype.

Expression of the transgene was confirmed by Western blot analysis of tissue protein levels. Briefly, whole tissue lysates were obtained from hearts or other organs of transgenic or control littermates. Thirty micrograms was loaded on SDS/PAGE gel, and blots were probed with anti-pro-Caspase3 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) or antiactive caspase3 (PharMingen). Bcl-2 and Bax antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Tissue Staining, Immunohistochemistry, and Electron Microscopy.

Ultrastructural analysis of morphological changes in transgenic mice was performed after fixing the heart in conventional fixing solutions (typically, 4% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer). Samples were processed (postfixation and dehydration) for embedding in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections, stained with uranyl acetate and lead hydroxide, were studied by using a CM-12 Philips electron microscope.

Immunoelectrogold microscopy was performed on thin heart sections (80 nm) fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Sorensen's phosphate buffer, embedded in Epon 812. Sections mounted on formavar-pretreated gold grids were incubated for 10 min with 10% H2O2, rinsed in distilled water, and treated with 1% BSA for 10 min to minimize nonspecific staining. Then, sections were eliminated of excess serum and incubated overnight at 4°C with cleaved caspase3-specific antibody (rabbit polyclonal antibody; New England Biolabs), anti-troponin C mAb (1A2, IgG2a; NovoCastra, Newcastle, U.K.), and isotype-matched control. After washing in PBS, bound mAb was performed by using a gold-conjugated goat antiserum to mouse or to rabbit (10 nm; Amersham Pharmacia) for 12 h at 4°C. Sections were counterstained with 2% uranyl acetate for 10 min and lead citrate for 1 min. Then, staining was observed.

The expression of Caspase3 by immunohistochemistry was performed according to conventional methodology. Briefly, serial frozen heart sections (5 μm) were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature and exposed to acetone for 10 min before starting the streptavidin–biotin-staining technique (Vectastain Universal Quick Kit; Vector Laboratories). Sections then were preblocked with 10% horse serum/PBS + 0.2% Tween 20 for 20 min at room temperature followed by elimination of excess serum from the session and incubation with specific antibody and isotype-matched control antibody at appropriate dilutions. For staining inactive pro-caspase3, caspase3 antiserum, purchased from Transduction Laboratories (see above), was used (1:500 dilution). For active Caspase, antiserum (CM1) was used (1:500 dilution; a gift from IDUN Pharmaceutical, La Jolla, CA) (13). After washing, bound antibodies were detected by a universal biotinylated antibody prediluted in TBS at room temperature for 20 min followed by incubation for 10 min with a peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin. ABC (3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole) was used as colorimetric substrate. Sections were rinsed, counterstained, and mounted in aqueous mounting medium. Analysis of tissue sections was performed by light microscopy.

Echocardiographic Analysis.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed in intact mice under anesthesia, and analysis was performed on all echocardiograms as described (14).

Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury, Infarct Size Determination, and DNA Laddering.

The procedures have been described extensively (15). Thoracotomy was performed in 13- to 15-week-old mice with an electrocautery (model 100; Geiger Instruments, Monarch Beach, CA). Ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was performed by using a 7-0 silk suture attached to a BV-1 needle (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). A small piece of polyethylene tubing was used to secure the ligature without damaging the artery. At 30 min of ischemia, the ligature was cut and removed from the heart. Reperfusion was confirmed visually in all animals by using a dissecting microscope. Animals that did not undergo complete LAD reperfusion were excluded from the study. At the conclusion of the 2- or 24-h period of reperfusion, the LAD was religated with 7-0 silk suture, and 1.2 ml of 1.0% Evans blue (Sigma) was injected retrogradely into the carotid artery catheter to delineate the in vivo area at risk (AAR). At the end of the protocol, the heart was excised and fixed in 1.5% solution of SeaPlaque agarose gel (FMC). After the gel solidified, the heart was sectioned perpendicular to the long axis in 1-mm portions by using a McIlwain (Westbury, NY) tissue chopper. The 1-mm sections were placed in individual wells of a six-well cell culture plate with the basal side exposed. Each slice was counterstained with 3.0 ml of 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Sigma) solution for 5 min at 37°C. Each slice was weighed and visualized under an Olympus SZ4045 dissecting microscope equipped with a Sony charge-coupled device iris-color video camera (Sony, Tokyo). The left ventricular area, AAR, and area of infarction for each slice then were determined by computer planimetry by using NIH IMAGE 1.57 software. The size of the myocardial infarction was determined by the following previously described equation (15): weight of infarction is (A1 × Wt1) + (A2 × Wt2) + (A3 × Wt3) + (A4 + Wt4) + (A5 + Wt5), where A is percent area of infarction by planimetry from subscripted numbers 1–5, representing sections, and Wt is the weight of the same numbered sections.

These experiments were performed on 13- to 15-week-old mice to avoid differences in cardiac function among transgenic and control mice.

For DNA-laddering experiments, DNA was extracted from total hearts after ischemia and 24-h reperfusion and run on 1.5% agarose gel, as described (16).

Statistical Analyses.

The data were analyzed with ANOVA and Scheffé's post hoc test. All values are reported as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Generation of Transgenic Lines and Expression of Capsase3 Transgene.

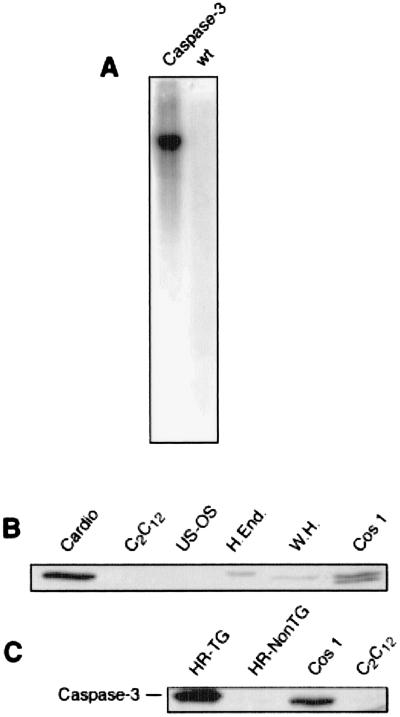

Of two transgenic lines overexpressing Caspase3 in the heart, one was characterized extensively (Fig. 1A). In all Caspase3 transgenic mice analyzed by Western blotting (more than 20), a band of 32 kDa was recognized from myocardial extracts by an anti-Caspase3-specific antibody, which comigrated with a similar band from other cell extracts. Caspase3 was overexpressed mostly in the heart, as compared with other organs (Fig. 1 B and C). The expression of Caspase3 also was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (not shown).

Figure 1.

(A) Southern blot of Caspase3 transgenic mice and control littermate. One band of ≈7.5 kb is clearly visible in TG but not control littermates. (B) Western blot of caspase3 from different cell types. Cardio, rat neonatal primary cardiomyocytes; C2C12, mouse skeletal muscle cell line; U2OS, human osteosarcoma cell line; H.End, HUVEC endothelial human cell line; W.H., whole heart tissue rat extract; Cos1, simian SV40 transformed cell line C; HR-TG, transgenic heart tissue extract; HR-NonTG, wild-type littermate control heart tissue extract.

Effects of Caspase3 Overexpression on Cardiac Function.

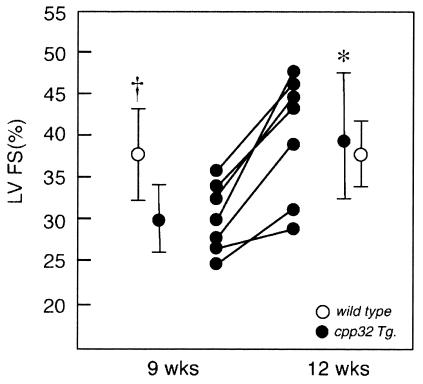

The effects of transgene expression on left ventricular (LV) function expressed as percent fractional shortening (%FS) and velocity of circumferential LV shortening (VCF) were determined by echocardiographic analysis. Studies in Caspase3 overexpressors conducted at 9 weeks demonstrated significantly decreased LV function [%FS, 29.9 + 3.85% (SD)] compared with age-matched, wild-type littermates (%FS, 36.9 ± 3.99%), (Fig. 2). VCF was also decreased compared with the wild-type mice (3.85 ± 0.72 c/sec vs. 4.8 ± 0.52 c/sec, respectively, P < 0.01). Importantly, a repeat echocardiographic study of the 9-week-old transgenic mice showed that the negative effects of Caspase3 on LV function had resolved at 12 weeks (VCF also significantly improved, data not shown) whereas in wild-type mice %FS (and VCF) at 12 weeks remained normal and unchanged (Fig. 2). At 4 months, the LV %FS also was not significantly different between transgenic and wild-type mice (data not shown). No significant differences in LV end-diastolic chamber diameter or wall-thickness values were detected between the groups.

Figure 2.

Effects of the transgene (solid symbols) of LV function by echocardiography, expressed as %FS, showing depressed function at 9 weeks, increasing to normal at 12 weeks; *, P < 0.01. Wild-type littermates (open symbols) showed significantly higher %FS at 9 weeks (†, P < 0.03), which remained normal at 12 weeks.

Morphological Effects of Caspase3 Expression on Cardiomyocytes.

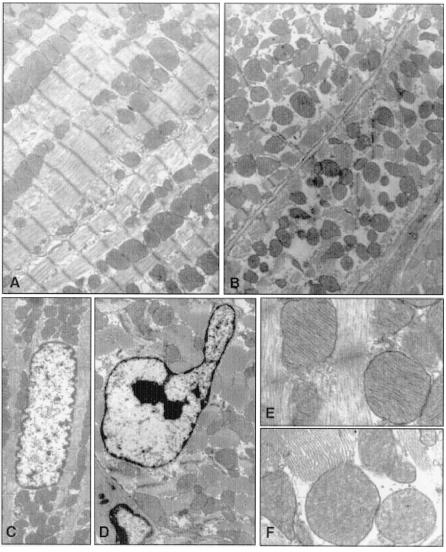

An uncontrolled and tissue-selective expression of Caspase3 might be expected to lead to extensive damage in cells in which the transgene is expressed. Therefore, we conducted an extensive morphological analysis on the myocardial tissue of these mice (Fig. 3). Five animals per group were analyzed.

Figure 3.

Ultrastructural changes in cardiomyocytes of caspase3 or control mice. (A and B) Myofibrillar morphology and content in control (A) and transgenic (B) mice. (C and D) Nuclear morphology in control (C) and transgenic (D) mice. (E and F) Mitochondrial ultrastructure in control (E) and transgenic (F) mice. Ultrastructural defects are present in cardiomyocytes of transgenic but not control mice.

Whereas hematoxylin/eosin and Mason threechromic staining did not reveal any increase in fibrous tissue content or gross cardiomyocyte defects (not shown), ultrastructural changes were visible in cardiomyocytes of Caspase3 transgenic animals. In particular, in some cells, a decrease in the myofibrillar content and myofibrillar disarray was evident. In other cardiomyocytes, it was possible to observe chromosomal nuclear condensation, typical of apoptotic nuclei. In these cells, the number of mitochondria was approximately similar; nonetheless, they were moderately swollen, with fragmentation of the cristae and damage to the inner membrane (Fig. 3). Such effects were present in mice less than 10 weeks of age, whereas they were less marked thereafter, thus correlating with the alteration of hemodynamic parameters.

Age-Related Changes in Active Caspase3, bcl-2, and Bax in the Myocardium.

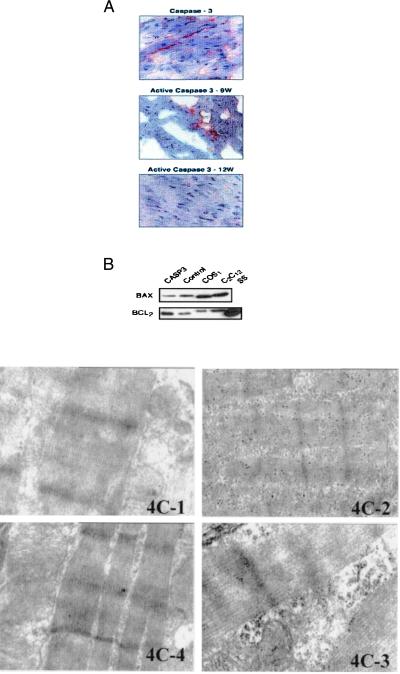

Caspase3 is in an inactive state, and when an apoptotic stimulus occurs it is cleaved into a biologically active peptide of ≈20 kDa and an inactive 12-kDa fragment (2). Efforts aimed at measuring the activity of the 20-kDa enzyme from tissues through fluorogenic assay were unfruitful, because of the high background of the reaction. Nevertheless, immunohistochemistry with an antibody specific for the active form of caspase3 was performed successfully. Using active caspase3 antiserum, we observed a higher number of positive cardiomyocytes at 9 weeks compared with that at 12 weeks. Similarly, the number of cardiomyocytes positive for full-length caspase3 decreased by 30% at 12 weeks compared with 9 weeks and by another 10% at 15 weeks compared with 12 weeks (Fig. 4A). Pro-caspase3 levels, as determined by Western blots, did not change between 9- and 12-week-old animals (not shown).

Figure 4.

(A) Immunohistochemical analysis of active and inactive caspase3. (Top) Immunohistochemical analysis with an antibody against full-length, inactive caspase3. (Middle) Immunohistochemical analysis with an antibody for active caspase3 in myocardial sections of transgenic animals 9 weeks old. (Bottom) Immunohistochemical analysis with an antibody for active caspase3 in myocardial sections of transgenic animals 12 weeks old. (B) Expression of Bax and Bcl2 in extracts from hearts of transgenic mice (casp3), control littermates, or COS and C2C12 cell lines. SS is a standard sample from cells overexpressing Bcl-2 by transfection. (C) Immunogold staining of active caspase3 on transgenic and nontransgenic hearts. 4C-1, Isotype-matched control; 4C-2, troponin C expression; 4C-3, cleaved caspase3 expression on 9-week-old transgenic animals; 4C-4, cleaved caspase3 expression on myocardial sections of 12-week-old transgenic animals. The gold staining is markedly positive in the myofibril disruption area of sections of transgenic animals 9 weeks old whereas it is reduced in 12-week-old mice.

A possible explanation for the transient effects determined by the overexpression of caspase3 may lie in the induction of compensatory regulation of pro- and antiapoptotic gene expression, leading to a new balance that allows cardiac cells to survive. We previously determined that in the myocardium of rats subjected to pressure overload, the proapoptotic Bax gene was up-regulated whereas the antiapoptotic Bcl2 was down-regulated (5). It seemed possible that modulation of these genes can compensate for the overexpression of caspase3. Therefore, an analysis of the expression of Bcl2 and Bax was conducted in caspase3 transgenic mice by Western blotting. Up-regulation of Bcl2 and down-regulation of Bax was observed in caspase3 transgenic mice compared with control littermates (Fig. 4B).

To investigate further the effects of age on caspase3 activity, immunogold staining with an antibody recognizing active caspase3 was performed on the myocardium of transgenic and nontransgenic animals at 9 and 12 weeks of age. Sections stained positive for active caspase3 at 9 weeks whereas expression was decreased markedly at 12 weeks (Fig. 4C).

Effects of Caspase3 Overexpression during Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury.

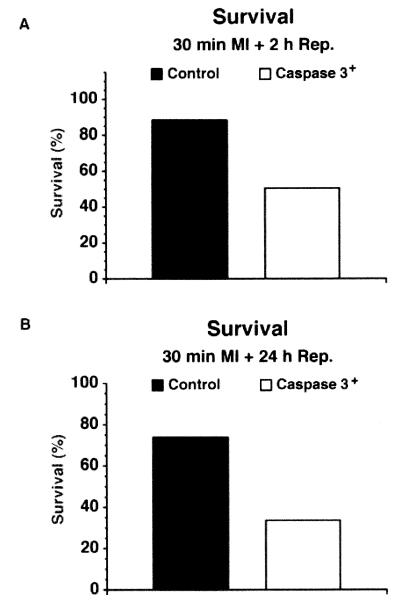

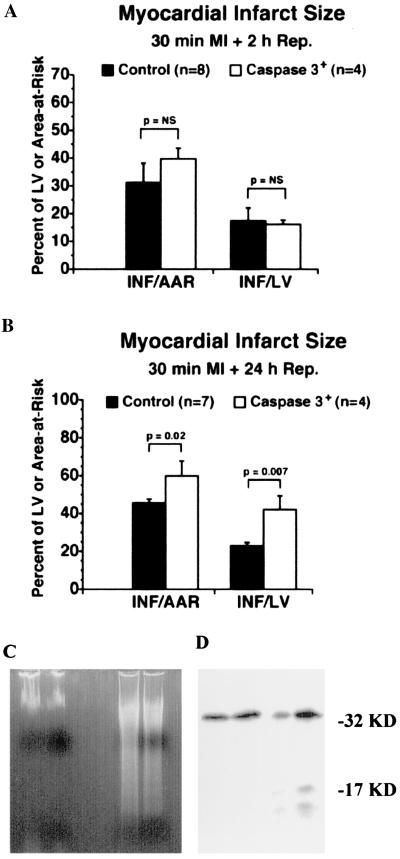

Thirteen- to 15-week-old mice were subjected to 30 min of ischemia followed by 2 or 24 h of reperfusion. Caspase3 mice were highly susceptible to death. In fact, only 45% and 30% of caspase3 mice were alive after 2 and 24 h of reperfusion, respectively, vs. 90% and 70% of control mice (Fig. 5). The effects of caspase3 overexpression on myocardial infarct size, expressed as the ratio between AAR and LV (AAR/LV), infarct size and AAR (I/AAR), and I and LV (I/LV), respectively, were determined at 2 and 24 h of reperfusion. At 2 h, there was no statistically significant difference in these parameters between transgenic and nontransgenic control mice (Fig. 6A). In contrast, at 24 h, two parameters (INF/AAR and INF/LV) were increased significantly in the transgenic group (Fig. 6B).

Figure 5.

Survival rate in mice undergoing 30 min of ischemia and reperfusion after 2 h (A) or 24 h (B). In the 30-min group, total survival number was 8/9 for control and 4/8 for transgenic animals, respectively. In the 24-h group, total survival was 7/9 for the control and 4/12 for the transgenic animals.

Figure 6.

Measures of myocardial infarct size in caspase3 and control mice after 30 min of ischemia and reperfusion after 2 h (A) or 24 h (B). (C Left) DNA ladder of total heart from nonischemic transgenic (first lane); nonischemic, nontransgenic (second lane); ischemic, 24-h-reperfused, transgenic (third lane); and ischemic, 24-h-reperfused, nontransgenic (fourth lane); hearts are shown in Inset. (C Right) A representative sample of Western blotting of caspase3 activation from total protein heart lysates of transgenic animals under normal conditions or subjected to ischemia and 24-h reperfusion (n = 2 per group). Cleavage of pro-caspase3 is demonstrated by the appearance of a 17-kDa fragment in the I-R group.

DNA laddering and caspase3 activation were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis and Western blotting, respectively. DNA was extracted from the hearts of untreated mice or transgenic and control mice undergoing ischemia–reperfusion and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis (16). Results showed a similar level of DNA laddering in transgenic and control mice undergoing ischemia–reperfusion, thus confirming that apoptosis is involved in the response to this type of insult both in control and caspase3-overexpressing animals (Fig. 6C Left). Also, an analysis of the state of caspase3 was conducted from total heart protein lysates of transgenic animals to determine whether caspase3 activation occurs during ischemia–reperfusion. A representative experiment is reported in Fig. 6C Right, in which cleavage of caspase3 is evident with ischemia–reperfusion but not in control transgenic animals.

Discussion

Here, we have investigated the effects on the myocardium of deregulated, cardiac-selective expression of caspase3 in mouse cardiomyocytes.

Caspase3 is known to be an important molecule in the cellular suicide cascade. It can be activated by stimuli with a membrane (receptor-activated) or mitochondrial origin (17). In fact, caspase3 is a downstream effector of caspase9, which, in turn, is activated by cytochrome c released by mitochondria or by caspase8 that is activated by membrane death receptors (17). Pro- and antiapoptotic genes of the Bcl2 family act by stabilizing (Bcl2-like) or destabilizing (Bax-like) the mitochondrial membrane, thus altering the release of cytochrome c that, in turn, activates caspase9 and caspase3 sequentially (18). On the other hand, membrane-dependent stimuli such as Fas/FasL or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)/TNF-αR interaction may trigger caspase8 activation, which eventually leads to caspase3 activation (17). Caspase3 protein levels are increased in myocardial specimens from patients with right ventricular arrythmogenic dysplasia (10), and caspase3 is present in its active form in the myocardium of end-stage heart failure patients (9). Apoptosis also has been described in experimental situations in which myocardial tissue is subjected to increased oxidative stress, such as the large generation of oxygen radicals occurring during cardiac reperfusion injury (11, 19). Therefore, it was of interest to consider whether cardiac function can be modified by caspase3 overexpression. Our data showed that overexpression of caspase3 depresses cardiac function, suggesting a role of caspase3 in regulating cardiac contractility. For the transient and age-dependent nature of this effect, two possible explanations can be considered. One relates to the decrease in activity of the α-MHC promoter with aging. Immunohistochemistry studies showed that the percentage of active Caspase decreased with age. In fact, myocardial sections from 12-week-old animals show a remarkable decrease in the number of cells positive for staining with the antiactive caspase3 as compared with 9-week-old mice. Recently, it was reported that transgenic mice generated with the α-MHC promoter expressed a transgene only transiently, although the effects on the cardiac phenotype were permanent (20). Therefore, the decreased activation of caspase3 with age might be a result of the reduced expression of the transgene. This possibility, however, seems to be excluded by the evidence that levels of pro-caspase3 are similar in heart extracts of 9- and 12-week-old animals. A second explanation, which does not exclude the first, is the activation of counterregulatory mechanisms in the capsase3 mice. This possibility is suggested by the increased expression of Bcl2 and decreased expression of Bax in myocardial tissue extracts in the aging animals.

Nitric oxide also has been shown to be a critical mediator of apoptosis and cell cycle in the cardiovascular system (21). Whether the effects of caspase3 on cardiac function and cardiomyocyte apoptosis can be controlled by nitric oxide or whether nitric oxide and caspase3 are mediators of the same pathway needs to be addressed.

Another aspect of the phenotype induced by caspase3 overexpression that deserves comment is the effect on cardiomyocyte structure. Transgenic caspase3 overexpression affected nuclear structure as well as mitochondrial and myofibrillar content. The number of cells affected by caspase3 overexpression varied from mouse to mouse. This can be due partly to a mosaic type of expression generated by using this promoter, thus inducing scattered expression of the transgene.

The structure of cardiomyocyte nuclei is modified under stress conditions. In fact, nuclear degeneration was reported in transgenic mice with cardiac-specific expression of the Gαs subunit during the cardiac decompensation phase (22). Moreover, a nuclear morphology similar to the one described herein was shown in the myocardium of rabbits subject to ischemia–reperfusion injury (19). Because both conditions are associated with increased oxidative stress, it is possible that caspase3 activation can mediate the deleterious effects of oxidation on subcellular structures.

An intriguing result of our study is the evidence that caspase3 overexpression, even in its partly activated state, is compatible with life. It can be speculated that caspase3 might have a role independent of its induction of cell death. In fact, in explanted hearts from patients undergoing heart transplantation, evidence of active caspase3 was found in a number of cardiomyocytes at levels higher than in cells with apoptotic nuclei (9). Thus, cytochrome c release and caspase3 activation also were present in nonapoptotic myocytes, implying that, in this cell type, survival is compatible with activation of only part of the caspase3 cellular content (23). This also would imply that, in cardiomyocytes, caspase3 may play other roles beyond regulating apoptosis, as shown in other cell types (24).

Our data also show that caspase3 overexpression predisposes to increased myocardial damage after coronary artery ligation, with ischemic tissue reperfused for 24 h, showing a significant increase of infarct size. Whether such an event was due to increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis or whether caspase3 predisposed to necrosis was not determined. Both effects can possibly contribute to the observed increased infarct size. Transgenic mice also showed a marked propensity to die. This effect might be a result of a rapid decrease of cardiac function from the sudden activation of caspase3 in a large number of cells after a potent oxidative stress such as the generation of oxygen radicals during ischemia–reperfusion (11). In this regard, it was shown previously that myocardial delivery of peptide inhibitors of caspase3 decreases the infarct size in rats (12). Future studies should determine the possibility of using peptide inhibitors of caspase3 and other caspases during pharmacological interventions for myocardial revascularization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association–Pennsylvania/Delaware Affiliate, Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Fondi 1% Ministero della Sanita' (to G.C.), and the National Institutes of Health (to C.M.C. and J.R.).

Abbreviations

- α-MHC

α-myosin heavy chain

- LAD

left anterior descending

- AAR

area at risk

- %FS

percent fractional shortening

- LV

left ventricular

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Steller H. Science. 1995;267:1445–1449. doi: 10.1126/science.7878463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornberry N A, Lazebnik Y. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Z, Bing O H, Long X, Robinson K G, Lakatta E G. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2313–H2319. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leri A, Liu Y, Malhotra A, Li Q, Stiegler P, Claudio P P, Giordano A, Kajstura J, Hintze T H, Anversa P. Circulation. 1998;97:194–203. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condorelli G L, Morisco C, Stassi G, Roncarati R, Farina F, Trimarco B, Lembo G. Circulation. 1999;23:3071–3078. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.23.3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narula J, Haider N, Virmani R, DiSalvo T G, Kolodgie F D, Hajjar R J, Schmidt U, Semigran M J, Dec G W, Khaw B A. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1182–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James T N. Coron Artery Dis. 1997;8:599–616. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199710000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabbah H N, Sharov V G, Gupta R C, Todor A, Singh V, Goldstein S. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1698–1705. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00913-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narula J, Pandey P, Arbustini E, Haider N, Narula N, Kolodgie F D, Dal Bello B, Semigran M J, Bielsa-Masdeu A, Dec G W, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8144–8149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mallat Z, Tedgui A, Fontaliran F, Frank R, Durigon M, Fontaine G. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1190–1196. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottlieb R A, Enlger R L. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;874:412–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaoita H, Ogawa K, Maehara K, Maruyama Y. Circulation. 1998;97:276–281. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krebs J F, Armstrong R C, Srinivasan A, Aja T, Wong A M, Aboy A, Sayers R, Pham B, Vu T, Hoang K, et al. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:915–926. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka N, Dalton N, Mao L, Rockman H A, Peterson K L, Gottshall K R, Hunter J J, Chien K R, Ross J., Jr Circulation. 1996;94:1109–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones S P, Girod W G, Palazzo A J, Granger D N, Grisham M B, Jourd'Heuil D, Huang P L, Lefer D. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1567–H1573. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bialik S, Geenen D L, Sasson I E, Cheng R, Horner J W, Evans S M, Lord E M, Koch C J, Kitsis R N. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1363–1372. doi: 10.1172/JCI119656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashkenazi A, Dixit V M. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green D R, Reed J C. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlieb R A, Burleson K O, Kloner R A, Babior B M, Engler R L. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1621–1628. doi: 10.1172/JCI117504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mende U, Kagen A, Cohen A, Aramburu J, Schoen F J, Neer E J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13893–13898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ignarro L, Cirino G, Casini A, Napoli C. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34:879–886. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199912000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geng Y J, Ishikawa Y, Vatner D E, Wagner T E, Bishop S P, Vatner S F, Homcy C J. Circ Res. 1999;84:34–42. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed J C, Paternostro G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7614–7616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeuner A, Eramo A, Peschle C, De Maria R. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1075–1080. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]