Abstract

Background

Male genital HPV prevalence and incidence has been reported to vary by geographical location. Our objective was to assess the natural history of genital HPV by country among men with a median of 48 months of follow-up.

Methods

Men aged 18–70 years were recruited from US (n=1326), Mexico (n=1349), and Brazil (n=1410). Genital specimens were collected every six months and HPV genotyping identified 37 HPV genotypes. Prevalence of HPV was compared between the three countries using the Fisher’s exact test. Incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. The median time to HPV clearance among men with an incident infection was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

The prevalence and incidence of the genital HPV types known to cause disease in males (HPV 16 and 6) was significantly higher among men from Brazil than men from Mexico. Prevalence and incidence of those genital HPV types in the US varied between being comparable to those of Mexico or Brazil. While genital HPV16 duration was significantly longer in Brazil (p=0.04) compared to Mexico and the US, HPV6 duration was shortest in Brazil (p=0.03) compared to Mexico and the US.

Conclusion

Men in Brazil and Mexico often have similar, if not higher prevalence of HPV compared to men from the U.S.

Impact

Currently there is no routine screening for genital HPV among males and while HPV is common in men, and most naturally clear the infection, a proportion of men do develop HPV-related diseases. Men may benefit from gender neutral vaccine policies.

Keywords: HIM Study, human papillomavirus (HPV), male, incidence, prevalence

Introduction

Infectious agents can interact with human hosts in a multitude of ways, and their ability to cause cancer is a major public health concern. Infectious agents caused 16% of the 12.7 million new cancer cases worldwide in 2008 (1). Four major agents are responsible for 80% of these infection-related cancers: hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, Helicobacter pylori, and human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV causes several types of cancers and genital warts in both males and females (2) and HPV can be transmitted through sexual contact and potentially through autoinoculation (3).

At the male genitals, HPV causes two types of external genital lesions: genital warts, and penile cancer. The HPV genotypes that are most frequently detected in genital warts are HPV6 and 11 (96–100%) (2, 4) and HPV 16 is the predominant type detected in penile cancer (5–11). Genital warts have a high likelihood of reoccurrence and multiple treatments can be costly (12). While penile cancer is considered a rare cancer with 22,000 estimated cases per year worldwide, it is associated with high morbidity and mortality (1).

Male genital HPV prevalence and incidence has been reported to vary by geographical location (13–15). Geographical differences in HPV prevalence may explain the differences in HPV-related cancer incidence worldwide. We previously have described the prevalence, incidence and duration (n=1159) of genital HPV by country among men from Brazil, Mexico and the United States (US) that were the first to enroll into the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study (16, 17). Here we expand our analyses, to the complete cohort of 4085 men with a median of 48 months of follow-up and describe the natural history of genital HPV by country, needed to inform vaccine policy discussion in each country.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The HIM Study enrolled 4123 men aged 18–70 years living in Tampa, Florida, US; Cuernavaca, Mexico; and Sao Paulo, Brazil between July 2005 and June 2009. A full description of the study procedures has been published (16, 17). Participants returned for study visits every six months and were given a physical exam where multiple specimens were obtained for laboratory analysis. Men who had two or more study visits were included in this analysis (n=4085). Among these 4085 men, 1410 were from Brazil, 1349 from Mexico, and 1326 from US.

All participants provided written informed consent. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of South Florida (Tampa, FL, US), the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, the Centro de Referencia e Treinamento em Doencas Sexualmente Transmissiveis e AIDS (Sao Paulo, Brazil), and the Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica (Cuernavaca, Mexico).

Genital skin specimen collection for HPV detection

Participants underwent a clinical examination at each visit. Using pre-wetted Dacron swabs, genital specimens were collected from the coronal sulcus/glans penis, penile shaft, and scrotum (17). These specimens were combined into one sample per participant and archived. Specimens underwent DNA extraction (Qiagen Media Kit), PCR analysis, and HPV genotyping (Roche Linear Array) (18). If samples tested positive for β-globin or an HPV genotype, they were considered adequate and were included in the analysis. The Linear Array assay tests for 37 HPV types, classified as high-risk (HR-HPV; types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) or low-risk (LR-HPV; types 6, 11, 26, 40, 42, 53, 54, 55, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 81, 82, 82 subtype IS39, 83, 84, and 89) (19). The HPV genotypes were further classified as the HPV types detected within the 4vHPV vaccine (6/11/16/18) and the 9vHPV vaccine (6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52/58). Non-4vHRHPV are the other High Risk (HR-HPV) HPV genotypes that are not covered by the 4vHPV vaccine (31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/ 68) and Non-9vHRHPV are the other HR-HPV genotypes that are not covered by the 9vHPV vaccine (35/39/51/56/59/68).

Statistical Analysis

In the HIM Study, sexual orientation was purposefully not asked to decrease risk of reporting bias of sexual behavior. Instead detailed information regarding sexual behavior was assessed and sex is defined as oral, vaginal or anal sex. Using responses to these questions at baseline, we defined MSM as ever having sex with a man, MSMW as having sex with both men and women, MSW only have sex with women and virgins are those that reported no sex with men or women.

Prevalence

Differences in demographic and sexual behavior characteristics between men who did or did not have a prevalent HPV infection (any HPV type) at baseline were calculated within each country using Monte Carlo estimation of the exact Pearson Chi-square test (Table 1). We also calculated differences in demographic and sexual behavior characteristics between men who did or did not have a prevalent HPV infection (any HPV type) at baseline across the three countries (global p-value) using the Wald Chi-square test. Prevalence of each HPV genotype was compared between the three countries using the Fisher’s exact test. To assess factors associated with prevalent HPV infection within each country, prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated with Poisson regression using robust variance estimation. Age was forced into the multivariable model and factors that remained in the final model were retained at p<0.05.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for 4085 men at HIM Study baseline comparing men with and without any prevalent HPV infection by country

| Brazil (n=1410) | Mexico (n=1349) | United States (n=1326) | Global p-valueb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No infection | Infection | P Valuea | No infection | Infection | P Valuea | No infection | Infection | P Valuea | ||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.87 | <.0001 | 0.11 | ||||||

| 18–30 | 207(37.2) | 350(62.8) | 284(50.9) | 274(49.1) | 508(58.3) | 364(41.7) | ||||

| 31–44 | 266(39.4) | 409(60.6) | 315(51.2) | 300(48.8) | 121(43.1) | 160(56.9) | ||||

| 45–74 | 88(49.4) | 90(50.6) | 86(48.9) | 90(51.1) | 75(43.4) | 98(56.6) | ||||

| Race | 0.55 | 0.73 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| White | 331(38.4) | 531(61.6) | 33(45.8) | 39(54.2) | 459(51.9) | 425(48.1) | ||||

| Black | 174(43.0) | 231(57.0) | 1(33.3) | 2(66.7) | 99(43.4) | 129(56.6) | ||||

| Asian/PI | 8(36.4) | 14(63.6) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 75(83.3) | 15(16.7) | ||||

| Other | 29(37.2) | 49(62.8) | 620(51.0) | 595(49.0) | 24(58.5) | 17(41.5) | ||||

| Refused | 19(44.2) | 24(55.8) | 31(52.5) | 28(47.5) | 47(56.6) | 36(43.4) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.81 | 0.60 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 126(38.3) | 203(61.7) | 677(50.6) | 662(49.4) | 110(53.9) | 94(46.1) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 426(40.6) | 622(59.4) | 3(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 589(52.8) | 527(47.2) | ||||

| Missing | 9(27.3) | 24(72.7) | 5(71.4) | 2(28.6) | 5(83.3) | 1(16.7) | ||||

| Years of Education | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.002 | 0.28 | ||||||

| ≤12 Years | 318(38.6) | 506(61.4) | 461(53.1) | 407(46.9) | 151(50.5) | 148(49.5) | ||||

| 13–15 Years | 75(38.3) | 121(61.7) | 54(41.9) | 75(58.1) | 408(57.5) | 302(42.5) | ||||

| ≥16 Years | 164(42.8) | 219(57.2) | 165(48.7) | 174(51.3) | 143(45.8) | 169(54.2) | ||||

| Missing | 4(57.1) | 3(42.9) | 5(38.5) | 8(61.5) | 2(40.0) | 3(60.0) | ||||

| Marital Status | 0.0002 | 0.01 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Single | 219(36.9) | 374(63.1) | 159(50.0) | 159(50.0) | 523(56.7) | 399(43.3) | ||||

| Married/Cohabiting | 300(44.8) | 369(55.2) | 502(52.3) | 458(47.7) | 120(48.8) | 126(51.2) | ||||

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 40(28.2) | 102(71.8) | 21(33.3) | 42(66.7) | 57(38.0) | 93(62.0) | ||||

| Missing | 2(33.3) | 4(66.7) | 3(37.5) | 5(62.5) | 4(50.0) | 4(50.0) | ||||

| Current Smoker | 0.01 | 0.04 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Current | 85(32.6) | 176(67.4) | 198(46.0) | 232(54.0) | 115(42.6) | 155(57.4) | ||||

| Former | 116(45.5) | 139(54.5) | 153(51.3) | 145(48.7) | 92(43.6) | 119(56.4) | ||||

| Never | 357(40.2) | 531(59.8) | 331(53.9) | 283(46.1) | 495(59.0) | 344(41.0) | ||||

| Missing | 3(50.0) | 3(50.0) | 3(42.9) | 4(57.1) | 2(33.3) | 4(66.7) | ||||

| Monthly Alcohol | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.16 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 0 drinks | 1(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 1(100.0) | 0(0.0) | ||||

| 1 – 30 drinks | 330(35.7) | 594(64.3) | 463(50.2) | 460(49.8) | 538(52.2) | 492(47.8) | ||||

| 31+ drinks | 11(35.5) | 20(64.5) | 10(32.3) | 21(67.7) | 2(25.0) | 6(75.0) | ||||

| Missing | 219(48.2) | 235(51.8) | 212(53.7) | 183(46.3) | 163(56.8) | 124(43.2) | ||||

| Sexual Orientation | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

| MSW | 332(40.3) | 491(59.7) | 532(50.2) | 527(49.8) | 538(51.0) | 517(49.0) | ||||

| MSM | 41(38.7) | 65(61.3) | 8(38.1) | 13(61.9) | 18(66.7) | 9(33.3) | ||||

| MSMW | 127(38.7) | 201(61.3) | 50(49.0) | 52(51.0) | 46(56.1) | 36(43.9) | ||||

| Virgins | 33(50.0) | 33(50.0) | 43(55.1) | 35(44.9) | 59(67.0) | 29(33.0) | ||||

| Missing | 28(32.2) | 59(67.8) | 52(58.4) | 37(41.6) | 43(58.1) | 31(41.9) | ||||

| Circumcised | 0.07 | 0.88 | 0.002 | 0.49 | ||||||

| No | 458(38.7) | 724(61.3) | 578(50.7) | 563(49.3) | 153(61.9) | 94(38.1) | ||||

| Yes | 103(45.2) | 125(54.8) | 107(51.4) | 101(48.6) | 551(51.1) | 528(48.9) | ||||

| Lifetime # of Female Partners | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 0–1 | 114(51.4) | 108(48.6) | 138(62.2) | 84(37.8) | 211(76.7) | 64(23.3) | ||||

| 2–9 | 202(50.0) | 202(50.0) | 383(54.0) | 326(46.0) | 312(61.4) | 196(38.6) | ||||

| 10–49 | 173(31.5) | 376(68.5) | 111(34.7) | 209(65.3) | 133(32.9) | 271(67.1) | ||||

| 50+ | 37(31.1) | 82(68.9) | 5(31.3) | 11(68.8) | 29(31.2) | 64(68.8) | ||||

| Refused | 35(30.2) | 81(69.8) | 48(58.5) | 34(41.5) | 19(41.3) | 27(58.7) | ||||

| Lifetime # of Male Partners | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.96 | ||||||

| 0 | 402(40.0) | 602(60.0) | 633(51.3) | 602(48.7) | 647(52.6) | 583(47.4) | ||||

| 1–9 | 86(36.1) | 152(63.9) | 41(48.2) | 44(51.8) | 38(64.4) | 21(35.6) | ||||

| 10+ | 57(44.2) | 72(55.8) | 5(35.7) | 9(64.3) | 7(36.8) | 12(63.2) | ||||

| Missing | 16(41.0) | 23(59.0) | 6(40.0) | 9(60.0) | 12(66.7) | 6(33.3) | ||||

Abbreviations: MSW: Men that have sex with only women; MSM: Men that have sex with only men; MSMW: men that have sex with men and women; Virgins: reported no sexual contact with male or female

P values were calculated using Monte Carlo estimation of exact Pearson chi-square tests comparing characteristics of men with and without HPV within each country. Missing values were not included in p value calculations.

Global p values were calculated using the Wald chi-square tests comparing the characteristics of men with and without HPV across the three countries. Missing values were not included in p value calculations.

Incidence and Clearance

Differences in baseline demographic and sexual behavior characteristics between men with and without an incident HPV infection (any HPV type) were calculated within each country using Monte Carlo estimation of the exact Pearson Chi-square test. We also calculated differences in baseline characteristics between men with and without an incident HPV infection across the three countries (global p-value) using the Wald Chi-square test.

Person time for newly acquired HPV infection was estimated by use of the time from study entry to the date of the first detection of HPV DNA, assuming a new infection arose at the date of detection. For individual and grouped HPV incidence analyses, only the first acquired infection was considered for a given HPV type or group. Incidence analyses included only men who tested negative for a given individual HPV type or grouped HPV infection category at baseline so for example men with any HPV type prevalent at enrollment were not included in the grouped “any HPV” incidence. The calculation of the exact 95% CIs for incidence estimates was based on the number of events modelled as a Poisson variable for the total person-months. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) and 95% CIs were also calculated based on Poisson assumption comparing incidence rates between countries.

HPV clearance was defined as two consecutive negative test results following a positive test, excluding infections detected for the first time at a participant’s final visit and prevalent infections. For grouped HPV clearance analyses, we adjusted for within-subject correlation, as men may have been infected with multiple HPV types within a defined group (e.g., positive for both HPV 16 and 18, which are both considered high-risk). The median time to HPV clearance (median duration) among men with an incident infection was estimated using the KM method for individual HPV infections, with the clustered KM method used for grouped HPV infections (20). To model the association between country and clearance, we employed Cox proportional hazards regression with and without the robust covariance matrix estimator for grouped and individual HPV clearance, respectively (21).

Results

Prevalence

The overall HPV (any type) prevalence among 4085 men participating in the HIM Study was 52.3%. Overall HPV (any type) prevalence did significantly differ (p<0.001) by country with Brazil (60.2%) having the highest prevalence compared to Mexico (49.2%) and the US (46.9%) (Table 2). In Brazil, HPV prevalence was associated with age (p=0.01), marital status (p=0.0002) and number of lifetime female sexual partners (p<0.0001) (Table 1). HPV prevalence in Mexico was not associated with age (p=0.87) but was associated with number of lifetime female sexual partners (p<0.0001). In the US, HPV prevalence was associated with age (p<0.0001), smoking status (p<0.0001), and number of lifetime female sexual partners (p<0.0001). When comparing demographic and sexual characteristics across the three countries, marital status (p<0.0001), smoking status (p<0.0001), and total number of female sexual partners (p<0.0001) were differentially associated with HPV prevalence (Table 1, global p-value).

Table 2.

Type distribution of prevalent HPV infections overall and by country among 4085 HIM Study participants.

| HPV Type | Brazil (n=1410) | Mexico (n=1349) | US (n=1326) | Pvaluea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | ||

| Any | 849 (60.2) | 664 (49.2) | 622 (46.9) | <0.001 |

| HR | 472 (33.5) | 365 (27.1) | 373 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| 16 | 130 (9.2) | 75 (5.6) | 112 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| 18 | 32 (2.3) | 20 (1.5) | 43 (3.2) | 0.01 |

| 31 | 30 (2.1) | 22 (1.6) | 21 (1.6) | 0.51 |

| 33 | 15 (1.1) | 5 (0.4) | 4 (0.3) | 0.02 |

| 35 | 38 (2.7) | 7 (0.5) | 21 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| 39 | 52 (3.7) | 51 (3.8) | 40 (3.0) | 0.50 |

| 45 | 28 (2.0) | 15 (1.1) | 25 (1.9) | 0.13 |

| 51 | 95 (6.7) | 85 (6.3) | 79 (6.0) | 0.71 |

| 52 | 64 (4.5) | 53 (3.9) | 42 (3.2) | 0.18 |

| 56 | 40 (2.8) | 20 (1.5) | 14 (1.1) | 0.002 |

| 58 | 54 (3.8) | 30 (2.2) | 14 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| 59 | 74 (5.2) | 75 (5.6) | 78 (5.9) | 0.77 |

| 68 | 32 (2.3) | 28 (2.1) | 35 (2.6) | 0.62 |

| LR | 688 (48.8) | 534 (39.6) | 453 (34.2) | <0.001 |

| 6 | 95 (6.7) | 82 (6.1) | 79 (6.0) | 0.66 |

| 11 | 20 (1.4) | 29 (2.1) | 6 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| 26 | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | 0.10 |

| 40 | 30 (2.1) | 23 (1.7) | 13 (1.0) | 0.05 |

| 42 | 27 (1.9) | 17 (1.3) | 13 (1.0) | 0.11 |

| 53 | 109 (7.7) | 51 (3.8) | 70 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| 54 | 36 (2.6) | 25 (1.9) | 30 (2.3) | 0.46 |

| 55 | 40 (2.8) | 35 (2.6) | 25 (1.9) | 0.24 |

| 61 | 98 (7.0) | 65 (4.8) | 27 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| 62 | 154 (10.9) | 87 (6.4) | 89 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| 64 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0.85 |

| 66 | 79 (5.6) | 55 (4.1) | 79 (6.0) | 0.06 |

| 67 | 9 (0.6) | 7 (0.5) | 4 (0.3) | 0.44 |

| 69 | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.75 |

| 70 | 51 (3.6) | 28 (2.1) | 24 (1.8) | 0.007 |

| 71 | 24 (1.7) | 36 (2.7) | 1 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| 72 | 29 (2.1) | 13 (1.0) | 10 (0.8) | 0.006 |

| 73 | 48 (3.4) | 11 (0.8) | 16 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| 81 | 63 (4.5) | 46 (3.4) | 17 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| 82 | 10 (0.7) | 7 (0.5) | 15 (1.1) | 0.19 |

| 82sb | 20 (1.4) | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| 83 | 43 (3.0) | 35 (2.6) | 36 (2.7) | 0.75 |

| 84 | 123 (8.7) | 104 (7.7) | 103 (7.8) | 0.56 |

| 89 | 107 (7.6) | 80 (5.9) | 93 (7.0) | 0.22 |

| 4vHPVc | 256 (18.2) | 187 (13.9) | 217 (16.4) | 0.009 |

| 9vHPVd | 376 (26.7) | 268 (19.9) | 278 (21.0) | <0.001 |

Note: HR= High Risk HPV types, LR= Low Risk HPV types

Pvalue calculated using the Fisher’s exact test comparing HPV prevalence in all three countries. Values in bold denote statistical significance.

HPV 82 subtype IS39

4vHPV: one or more of the 4-valent HPV vaccine types (6, 11, 16,18)

9vHPV: one or more of the 4-valent HPV vaccine types (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58)

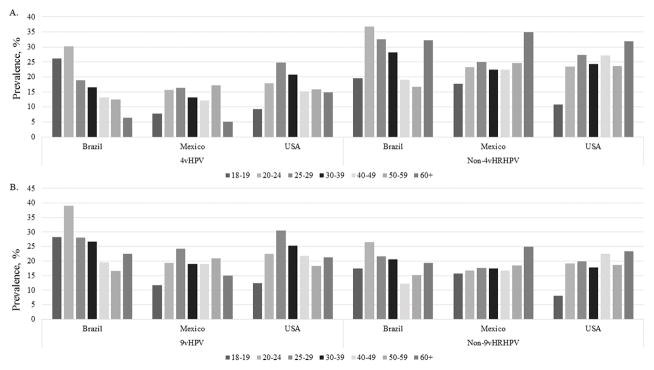

HPV genotype prevalence by country is described in Table 2. Prevalence of several HPV types significantly differed by country. HPV16 prevalence was highest among men from Brazil (9.2%) compared to men from Mexico (5.6%) and the US (8.4%). HPV6 prevalence, which causes genital warts was comparable between the three countries (p=0.66). Men from Brazil (18.2%) and the US (16.4%) have a higher proportion of having one of the 4vHPV types detected at the genitals compared to men from Mexico (13.9%). The prevalence of 4vHPV types and Non-4vHRHPV types by age category and country is presented in Figure 1A. In Brazil, the prevalence of 4vHPV types seems to decrease with age, and we did not see this similar trend in Mexico or the US. In contrast, the prevalence of the non-4vHPV types by country and age is surprisingly high in the oldest age group 60+ in all three countries and is lowest among the 18–19 year olds in Mexico and the US compared to the older ages. The prevalence of 9vHPV types and Non-9vHRHPV types by age category and country is presented in Figure 1B. Non-9vHRHPV prevalence seemed to stay consistent across the age groups in all three countries.

Figure 1. Prevalence of genital HPV by country and age category at baseline.

A.) 4vHPV and Non-4vHRHPV B.) 9vHPV and Non-9vHRHPV. Categories for 4vHPV, Non-4vHPV, 9vHPV, and Non-9vHPV are not mutually exclusive.

Factors associated with a prevalent HPV infection by country are shown in Table 3 and all final models were adjusted for age in each country. Final models for the prevalence of any HPV in each country were independently associated with increasing number of lifetime female sexual partners: adjusted PR (aPR) =1.47, 95% CI= 1.22–1.77 in Brazil, aPR=1.90, 95% CI=1.23–2.93 in Mexico, and aPR=4.44, 95% CI 2.92–6.76 in US comparing 50 or more lifetime female sexual partners compared to one or less female sexual partner (Table 3). Other factors associated with genital HPV prevalence varied from country to country. In Brazil, prevalence of HPV was associated with being divorced/separated/widowed (aPR=1.18, 95% CI = 1.0–1.35) compared to being single, and having more than 31 alcohol drink per month (aPR= 1.20, 95% CI= 1.06–1.36) compared to no alcohol drinks. In Mexico, increasing number of recent female sex partners in the past six months (more than 3 partners compared to none, aPR= 1.47, 95% CI = 1.22–1.77) and MSM compared to MSW (aPR= 1.90, 95% CI= 1.16–3.11) was also associated with prevalence of HPV. Having at least one male anal sex partner in the past six months (aPR= 1.98, 95% CI= 1.26–3.10) and being a virgin (aPR= 2.13, 95% CI= 1.30–3.47) compared to MSW was associated with HPV prevalence in the US. Not being circumcised in the US was associated with lower HPV prevalence (aPR= 0.83, 95% CI= 0.70–0.98).

Table 3.

Factors associated with a prevalent infection (Any HPV) by country

| Brazil (n=1410) | Mexico (n=1349) | United States (n=1326) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| uPR | aPR | uPR | aPR | uPR | aPR | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–30 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 31–44 | 0.96(0.88–1.05) | 0.95(0.86–1.05) | 0.99(0.88–1.12) | 0.99(0.88–1.12) | 1.36(1.20–1.55) | 0.98(0.86–1.13) |

| 45–74 | 0.8(0.69–0.94) | 0.75(0.63–0.90) | 1.04(0.88–1.23) | 1.03(0.87–1.22) | 1.36(1.17–1.58) | 0.99(0.84–1.16) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 0.96(0.87–1.06) | NE | 1.02(0.87–1.20) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |||

| Black | 0.93(0.84–1.02) | 1.23(0.54–2.82) | 1.18(1.03–1.34) | |||

| Asian/PI | 1.03(0.75–1.42) | NE | 0.35(0.22–0.55) | |||

| Other | 1.02(0.85–1.22) | 0.9(0.73–1.13) | 0.86(0.60–1.25) | |||

| Refused | 0.91(0.69–1.19) | 0.88(0.62–1.23) | 0.9(0.70–1.16) | |||

| Education | ||||||

| ≤12 Years | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 13–15 Years | 1.01(0.89–1.14) | 1.24(1.05–1.46) | 1.17(1.00–1.37) | 0.86(0.74–0.99) | ||

| ≥16 Years | 0.93(0.84–1.03) | 1.09(0.97–1.24) | 1.02(0.90–1.16) | 1.09(0.94–1.28) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Married/Cohabiting | 0.87(0.80–0.96) | 0.91(0.82–1.00) | 0.95(0.84–1.08) | 1.18(1.03–1.36) | ||

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 1.14(1.01–1.28) | 1.18(1.02–1.35) | 1.33(1.08–1.64) | 1.43(1.24–1.66) | ||

| Smoking Status | ||||||

| Never | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |||

| Current | 1.13(1.02–1.25) | 1.17(1.04–1.32) | 1.40(1.23–1.60) | |||

| Former | 0.91(0.80–1.03) | 1.06(0.91–1.22) | 1.38(1.19–1.59) | |||

| Monthly Alcohol Intake | ||||||

| 0 drinks | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 1 – 30 drinks | 1.23(1.10–1.38) | 1.18(1.05–1.32) | 1.1(0.95–1.27) | 1.02(0.86–1.21) | ||

| 31+ drinks | 1.33(1.18–1.50) | 1.20(1.06–1.36) | 1.21(1.02–1.42) | 1.24(1.06–1.46) | ||

| Circumcised | ||||||

| Yes | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| No | 1.12(0.98–1.27) | 1.12(0.99–1.27) | 1.02(0.87–1.18) | 0.78(0.66–0.92) | 0.83(0.70–0.98) | |

| Lifetime Number of Female Sex Partners | ||||||

| 0–1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 2–9 | 1.03(0.87–1.21) | 1.08(0.91–1.28) | 1.22(1.01–1.46) | 1.4(1.06–1.84) | 1.66(1.30–2.11) | 2.45(1.63–3.67) |

| 10–49 | 1.41(1.22–1.63) | 1.44(1.23–1.68) | 1.73(1.43–2.08) | 1.85(1.39–2.47) | 2.88(2.30–3.61) | 4.32(2.90–6.44) |

| 50+ | 1.42(1.18–1.70) | 1.47(1.22–1.77) | 1.82(1.25–2.63) | 1.90(1.23–2.93) | 2.96(2.29–3.81) | 4.44(2.92–6.76) |

| Refused | 1.44(1.20–1.72) | 1.40(1.14–1.73) | 1.10(0.81–1.49) | 1.35(0.73–2.49) | 2.52(1.82–3.49) | 1.25(0.17–9.10) |

| Lifetime Number of Male Anal Sex Partners | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |||

| 1–9 | 1.07(0.96–1.19) | 1.06(0.86–1.31) | 0.75(0.53–1.06) | |||

| 10+ | 0.93(0.79–1.09) | 1.32(0.89–1.96) | 1.33(0.94–1.89) | |||

| Missing | 0.98(0.75–1.28) | 1.23(0.81–1.87) | 0.70(0.36–1.36) | |||

| Recent Number of Female Sex Partners in past 6 months | ||||||

| None | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 1 | 1.02(0.90–1.16) | 1.14(0.99–1.31) | 1.13(0.97–1.32) | 1.33(1.12–1.56) | ||

| 2 | 1.34(1.18–1.52) | 1.53(1.31–1.78) | 1.36(1.14–1.62) | 1.49(1.20–1.86) | ||

| 3+ | 1.43(1.28–1.61) | 1.67(1.41–1.98) | 1.40(1.16–1.70) | 1.97(1.66–2.35) | ||

| Refused | 1.39(1.15–1.70) | 1.16(0.90–1.48) | 1.19(0.86–1.65) | 1.75(1.18–2.60) | ||

| Recent Number of Male Anal Sex Partners in past 6 months | ||||||

| None | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 1+ | 1.03(0.91–1.16) | 1.02(0.7–1.48) | 1.04(0.76–1.43) | 1.98(1.26–3.10) | ||

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||

| MSW | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| MSM | 1.03(0.87–1.21) | 1.24(0.88–1.75) | 1.90(1.16–3.11) | 0.68(0.40–1.16) | 1.29(0.59–2.83) | |

| MSMW | 1.03(0.93–1.14) | 1.02(0.84–1.25) | 0.94(0.77–1.15) | 0.90(0.70–1.15) | 0.69(0.51–0.93) | |

| Virgins | 0.84(0.65–1.07) | 0.90(0.70–1.16) | 1.54(1.08–2.20) | 0.67(0.50–0.91) | 2.13(1.30–3.47) | |

Abbreviations: MSW: Men that have sex with only women; MSM: Men that have sex with only men; MSMW: men that have sex with men and women; Virgins: reported no sexual contact with male or female

Prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CI were calculated with Poisson regression using robust variance estimation. Age was forced into the multivariable model and factors that remained in the final model were p<0.05.

Incidence

The median follow-up time for men from Brazil was 49.9 months (interquartile range (IQR)= 47.7–52.9), 47.6 months (IQR=29.4–55.0) for men from Mexico, and 43.2 months (IQR=12.8–50.4) for men from the US. Among the 4085 men, 86% from Brazil, 65% from Mexico, and 66% from the US had an incident HPV (any type) infection during follow-up. Table 4 is describing differences in demographic and sexual characteristics at baseline associated with any HPV incidence. In all three countries lifetime number of female sexual partners and marital status were significantly associated with any HPV incidence (Table 4). Lifetime number of male sexual partners and sexual orientation was significantly associated with any HPV incidence in Brazil and Mexico but not in the US. HPV incidence was significantly associated with alcohol consumption in Mexico and the US, but not in Brazil. While in the US, HPV incidence was associated with race (p=<0.0001) and smoking status (p=0.02). When comparing demographic and sexual characteristics across the three countries, race (p<0.0001), marital status (p<0.0001), smoking status (p<0.0001), alcohol consumption (p<0.0001), sexual orientation (p<0.0001), and total number of female sexual partners (p<0.0001) were differentially associated with HPV incidence (Table 4, global p-value).

Table 4.

Demographic characteristics of 4085 HIM study participants at baseline comparing men with and without an incident HPV infection during follow-up by country

| Factors | Brazil (n=1410) | Mexico (n=1349) | United States (n=1326) | Global pvalueb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No infection | Infection | P Valuea | No infection | Infection | P Valuea | No infection | Infection | P Valuea | ||

| Age | 0.75 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.33 | ||||||

| 18–30 | 73(13.1) | 484(86.9) | 201(36.0) | 357(64.0) | 316(36.2) | 556(63.8) | ||||

| 31–44 | 96(14.2) | 579(85.8) | 224(36.4) | 391(63.6) | 81(28.8) | 200(71.2) | ||||

| 45–74 | 27(15.2) | 151(84.8) | 53(30.1) | 123(69.9) | 55(31.8) | 118(68.2) | ||||

| Race | 0.76 | 0.82 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| White | 121(14) | 741(86) | 23(31.9) | 49(68.1) | 289(32.7) | 595(67.3) | ||||

| Black | 51(12.6) | 354(87.4) | 1(33.3) | 2(66.7) | 64(28.1) | 164(71.9) | ||||

| Asian/PI | 4(18.2) | 18(81.8) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 53(58.9) | 37(41.1) | ||||

| Other | 12(15.4) | 66(84.6) | 430(35.4) | 785(64.6) | 17(41.5) | 24(58.5) | ||||

| Refused | 8(18.6) | 35(81.4) | 24(40.7) | 35(59.3) | 29(34.9) | 54(65.1) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 0.72 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.49 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 43(13.1) | 286(86.9) | 475(35.5) | 864(64.5) | 66(32.4) | 138(67.6) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 147(14.0) | 901(86.0) | 1(33.3) | 2(66.7) | 383(34.3) | 733(65.7) | ||||

| Missing | 6(18.2) | 27(81.8) | 2(28.6) | 5(71.4) | 3(50.0) | 3(50.0) | ||||

| Years of Education | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 0.20 | ||||||

| ≤12 Years | 126(15.3) | 698(84.7) | 313(36.1) | 555(63.9) | 107(35.8) | 192(64.2) | ||||

| 13–15 Years | 21(10.7) | 175(89.3) | 53(41.1) | 76(58.9) | 237(33.4) | 473(66.6) | ||||

| ≥16 Years | 49(12.8) | 334(87.2) | 107(31.6) | 232(68.4) | 106(34.0) | 206(66.0) | ||||

| Missing | 0(0.0) | 7(100.0) | 5(38.5) | 8(61.5) | 2(40.0) | 3(60.0) | ||||

| Marital Status | 0.01 | 0.0001 | 0.007 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Single | 66(11.1) | 527(88.9) | 100(31.4) | 218(68.6) | 337(36.6) | 585(63.4) | ||||

| Married/Cohabiting | 113(16.9) | 556(83.1) | 367(38.2) | 593(61.8) | 77(31.3) | 169(68.7) | ||||

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 17(12.0) | 125(88.0) | 7(11.1) | 56(88.9) | 36(24.0) | 114(76.0) | ||||

| Missing | 0(0.0) | 6(100.0) | 4(50.0) | 4(50.0) | 2(25.0) | 6(75.0) | ||||

| Current Smoker | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.02 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Current | 30(11.5) | 231(88.5) | 141(32.8) | 289(67.2) | 89(33.0) | 181(67.0) | ||||

| Former | 29(11.4) | 226(88.6) | 108(36.2) | 190(63.8) | 55(26.1) | 156(73.9) | ||||

| Never | 137(15.4) | 751(84.6) | 225(36.6) | 389(63.4) | 306(36.5) | 533(63.5) | ||||

| Missing | 0(0.0) | 6(100.0) | 4(57.1) | 3(42.9) | 2(33.3) | 4(66.7) | ||||

| Monthly Alcohol | 0.10 | 0.002 | 0.0003 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 0 drinks | 64(16.2) | 330(83.8) | 133(41.0) | 191(59.0) | 102(38.8) | 161(61.2) | ||||

| 1 – 30 drinks | 84(14.1) | 510(85.9) | 251(35.8) | 451(64.2) | 205(37.6) | 340(62.4) | ||||

| 31+ drinks | 38(10.9) | 312(89.1) | 66(26.2) | 186(73.8) | 136(27.6) | 357(72.4) | ||||

| Missing | 10(13.9) | 62(86.1) | 28(39.4) | 43(60.6) | 9(36.0) | 16(64.0) | ||||

| Sexual Orientation | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.10 | <.0001 | ||||||

| MSW | 133(16.2) | 690(83.8) | 376(35.5) | 683(64.5) | 357(33.8) | 698(66.2) | ||||

| MSM | 9(8.5) | 97(91.5) | 1(4.8) | 20(95.2) | 9(33.3) | 18(66.7) | ||||

| MSMW | 32(9.8) | 296(90.2) | 30(29.4) | 72(70.6) | 22(26.8) | 60(73.2) | ||||

| Virgins | 11(16.7) | 55(83.3) | 32(41) | 46(59) | 39(44.3) | 49(55.7) | ||||

| Missing | 11(12.6) | 76(87.4) | 39(43.8) | 50(56.2) | 25(33.8) | 49(66.2) | ||||

| Circumcised | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.10 | ||||||

| No | 164(13.9) | 1018(86.1) | 414(36.3) | 727(63.7) | 92(37.2) | 155(62.8) | ||||

| Yes | 32(14.0) | 196(86.0) | 64(30.8) | 144(69.2) | 360(33.4) | 719(66.6) | ||||

| Lifetime # of Female Partners | 0.0006 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 0–1 | 38(17.1) | 184(82.9) | 104(46.8) | 118(53.2) | 124(45.1) | 151(54.9) | ||||

| 2–9 | 76(18.8) | 328(81.2) | 273(38.5) | 436(61.5) | 187(36.8) | 321(63.2) | ||||

| 10–49 | 52(9.5) | 497(90.5) | 66(20.6) | 254(79.4) | 104(25.7) | 300(74.3) | ||||

| 50+ | 16(13.4) | 103(86.6) | 1(6.3) | 15(93.8) | 23(24.7) | 70(75.3) | ||||

| Refused | 14(12.1) | 102(87.9) | 34(41.5) | 48(58.5) | 14(30.4) | 32(69.6) | ||||

| Lifetime # of Male Partners | 0.007 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.003 | ||||||

| 0 | 159(15.8) | 845(84.2) | 447(36.2) | 788(63.8) | 423(34.4) | 807(65.6) | ||||

| 1–9 | 23(9.7) | 215(90.3) | 24(28.2) | 61(71.8) | 19(32.2) | 40(67.8) | ||||

| 10+ | 13(10.1) | 116(89.9) | 1(7.1) | 13(92.9) | 5(26.3) | 14(73.7) | ||||

| Missing | 1(2.6) | 38(97.4) | 6(40.0) | 9(60.0) | 5(27.8) | 13(72.2) | ||||

Abbreviations: MSW: Men that have sex with only women; MSM: Men that have sex with only men; MSMW: men that have sex with men and women; Virgins: reported no sexual contact with male or female at baseline

P values were calculated using Monte Carlo estimation of exact Pearson chi-square tests comparing characteristics of men with and without HPV within each country. Missing values were not included in p value calculations.

Global p values were calculated using the Wald chi-square tests comparing the characteristics of men with and without HPV across the three countries. Missing values were not included in p value calculations.

Incidence rates (IR) per 1000 person-months (pm) for HPV are presented for each country (Table 5) and IRR were calculated to compare the rates between countries. Any HPV incidence was significantly higher among men from Brazil compared to men from the US (IRR=1.5, 95%CI=1.3–1.7) and significantly lower among men from Mexico compared to men from the US (IRR=0.7, 95%CI=0.6–0.8). No difference in HPV 16 incidence was observed between Brazil and the US; however, HPV16 incidence in Mexico was significantly lower than the US (IRR=0.6, 95%CI=0.5–0.7). The incidence of HPV6 was significantly higher among men from Brazil compared to men from the US (IRR=1.3, 95%CI=1.0–1.6); no difference between Mexico and the US was observed. Similar country trends were observed for HPV11 incidence. In general, Brazil had the highest incidence of other HPV types compared to the US and Mexico generally had the lowest HPV incidence.

Table 5.

Incidence rates and median duration of incident genital HPV infections by country of residence

| HPV | INCIDENCE | DURATION | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | Mexico | US | Brazil vs US | Mexico vs US | Median duration, months (95% CI) | ||||

| IR (95%CI) | IR (95%CI) | IR (95%CI) | IRR (95%CI) | IRR (95%CI) | Brazil | Mexico | US | pvaluea | |

| Any | 43.2 (39.4–47.3) | 20.9 (18.8–23.1) | 29.8 (27.0–32.8) | 1.5(1.3–1.7) | 0.7(0.6–0.8) | 6.6 (6.5–6.7) | 7.0 (6.9–7.3) | 6.5 (6.4–6.6) | <0.0001 |

| HR | 22.2 (20.4–24.1) | 12.4 (11.2–13.7) | 19.0 (17.3–20.9) | 1.2(1.0–1.3) | 0.7(0.6–0.7) | 6.7 (6.5–6.9) | 7.1 (6.7–7.8) | 6.4 (6.3–6.5) | <0.0001 |

| 16 | 4.5 (3.9–5.1) | 2.7 (2.2–3.1) | 4.6 (3.9–5.3) | 1.0(0.8–1.2) | 0.6(0.5–0.7) | 6.7 (6.4–7.2) | 6.6 (6.1–8.4) | 6.6 (6.3–7.3) | 0.04 |

| 18 | 2.3 (2.0–2.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 1.9 (1.5–2.4) | 1.2(0.9–1.6) | 0.4(0.3–0.6) | 7.1 (6.3–8.5) | 8.1 (6.2–15.0) | 6.2 (6.2–6.4) | 0.56 |

| 31 | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.9(0.7–1.3) | 0.8(0.6–1.2) | 6.6 (6.0–7.4) | 11.9 (8.3–14.7) | 6.4 (6.0–6.7) | <0.0001 |

| 33 | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 1.6(0.9–2.8) | 0.4(0.2–0.9) | 6.4 (5.8–11.7) | 6.3 (5.0–12.0) | 6.0 (6.0–6.5) | 0.01 |

| 35 | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 1.6(1.1–2.3) | 0.2(0.1–0.5) | 9.4 (6.4–13.1) | 6.6 (5.8–12.0) | 6.9 (6.1–12.0) | 0.03 |

| 39 | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 2.6 (2.1–3.1) | 0.8(0.6–1.1) | 0.7(0.5–0.9) | 6.9 (6.1–10.8) | 12.0 (7.0–17.5) | 7.1 (6.4–9.2) | 0.01 |

| 45 | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | 1.3(0.9–1.7) | 0.6(0.4–0.8) | 6.5 (6.1–7.2) | 6.2 (5.9–7.3) | 6.2 (6.0–6.4) | 0.04 |

| 51 | 4.9 (4.3–5.5) | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | 4.8 (4.1–5.5) | 1.0(0.8–1.2) | 0.5(0.4–0.6) | 6.7 (6.2–7.5) | 9.4 (7.1–12.7) | 6.4 (6.2–7.2) | 0.0009 |

| 52 | 3.7 (3.2–4.2) | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) | 1.5(1.2–1.9) | 0.7(0.5–1.0) | 6.8 (6.4–7.7) | 7.0 (6.0–10.8) | 6.2 (6.0–6.4) | 0.0001 |

| 56 | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.3(0.9–1.8) | 0.7(0.5–1.0) | 8.3 (6.4–11.7) | 6.1 (5.8–9.8) | 6.2 (6.1–6.7) | 0.006 |

| 58 | 2.0 (1.7–2.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.6(1.2–2.2) | 0.9(0.6–1.2) | 7.2 (6.6–11.0) | 9.2 (6.2–12.5) | 6.6 (6.1–11.7) | 0.39 |

| 59 | 3.2 (2.8–3.7) | 2.7 (2.2–3.2) | 3.7 (3.2–4.4) | 0.9(0.7–1.1) | 0.7(0.6–0.9) | 6.4 (6.0–6.7) | 6.4 (6.0–7.8) | 6.2 (6.2–6.8) | 0.006 |

| 68 | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.6(1.2–2.2) | 1.1(0.8–1.6) | 6.2 (6.0–6.7) | 6.5 (6.0–7.3) | 6.7 (6.4–8.8) | 0.55 |

| LR | 34.1 (31.2–37.1) | 16.2 (14.6–17.9) | 21.8 (19.8–24) | 1.6(1.4–1.8) | 0.7(0.6–0.9) | 6.6 (6.4–6.7) | 7 (6.8–7.5) | 6.6 (6.5–6.7) | <0.0001 |

| 6 | 3.7 (3.2–4.3) | 2.6 (2.2–3.1) | 2.9 (2.4–3.5) | 1.3(1.0–1.6) | 0.9(0.7–1.1) | 6.2 (6.0–6.6) | 6.7 (6.3–7.9) | 6.9 (6.4–7.9) | 0.03 |

| 11 | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 2.4(1.5–3.6) | 1.1(0.7–1.8) | 6.3 (6.2–6.9) | 6.9 (6.0–11.5) | 7.1 (6.0–13.6) | 0.17 |

| 26 | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 1.7(0.9–3.3) | 0.2(0.1–0.6) | 6.2 (6.0–11.7) | 6.0 (5.8–6.3) | 6.5 (6.2–13.1) | 0.65 |

| 40 | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.1(0.8–1.6) | 0.5(0.3–0.8) | 7.0 (6.4–8.5) | 6.3 (5.8–12.3) | 6.5 (6.1–12.3) | 0.91 |

| 42 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 1.5(1.1–2.2) | 0.8(0.5–1.2) | 8.2 (6.9–12.0) | 6.9 (6.0–12.8) | 6.5 (6.1–7.6) | <0.0001 |

| 53 | 4.5 (4.0–5.1) | 2.6 (2.1–3.0) | 3.2 (2.7–3.8) | 1.4(1.1–1.7) | 0.8(0.6–1.0) | 6.6 (6.2–7.2) | 6.8 (6.1–10.5) | 6.2 (6.0–6.7) | 0.04 |

| 54 | 2.8 (2.4–3.3) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 2.7 (2.3–3.3) | 1.0(0.8–1.3) | 0.5(0.4–0.7) | 6.5 (6.2–8.0) | 10.5 (6.5–15.7) | 6.6 (6.4–8.1) | 0.38 |

| 55 | 2.0 (1.7–2.4) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 1.3(1.0–1.8) | 0.4(0.3–0.6) | 6.5 (6.2–8.0) | 6.9 (6.2–9.0) | 6.7 (6.2–9.2) | 0.67 |

| 61 | 4.7 (4.1–5.3) | 1.6 (1.2–1.9) | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | 2.2(1.7–2.8) | 0.7(0.6–1.0) | 6.3 (6.0–6.8) | 9.7 (6.9–15.0) | 6.6 (6.2–10.6) | 0.01 |

| 62 | 6.1 (5.4–6.8) | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | 3.8 (3.2–4.5) | 1.6(1.3–1.9) | 0.5(0.4–0.7) | 6.6 (6.4–7.1) | 6.9 (6.3–9.8) | 6.8 (6.4–8.0) | 0.26 |

| 64 | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) | 5.6(1.3–24.5) | 3.2(0.7–15.0) | 6.0 (5.7–10.6) | 6.0 (5.6–6.4) | 6 (0.6–6.8) | 0.31 |

| 66 | 3.8 (3.3–4.3) | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | 3.9 (3.3–4.6) | 1.0(0.8–1.2) | 0.5(0.4–0.6) | 6.5 (6.2–7.1) | 10.4 (7.2–11.9) | 6.7 (6.3–7.4) | 0.0006 |

| 67 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 1.7(1.0–2.8) | 1.0(0.6–1.8) | 6.0 (6.0–6.8) | 6.9 (6.2–10.9) | 6.1 (6.0–6.7) | 0.01 |

| 69 | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 2.4(1.0–5.6) | 0.7(0.2–2.0) | 5.9 (5.8–6.4) | 6.6 (0.9–17.0) | 6.0 (0.4–7.9) | 0.20 |

| 70 | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 2.9(2.0–4.3) | 1.0(0.6–1.6) | 6.3 (6.2–6.7) | 6.7 (6.1–9.6) | 6.4 (6.0–7.2) | 0.99 |

| 71 | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 4.2(2.2–8.2) | 4.4(2.2–8.7) | 7.1 (6.0–12.2) | 6.7 (6.2–12.7) | 6.0 (5.5–20.4) | 0.22 |

| 72 | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 1.7(1.2–2.5) | 0.6(0.4–0.9) | 6.4 (6.1–7.8) | 6.7 (6.1–17.9) | 6.2 (6.0–6.7) | 0.07 |

| 73 | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.4(1.0–1.9) | 0.3(0.2–0.5) | 6.7 (6.2–9.2) | 7.9 (6.1–12.4) | 7.1 (6.3–11.8) | 0.54 |

| 81 | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 2.8(2.0–4.0) | 1.4(0.9–2.0) | 6.8 (6.5–7.9) | 6.9 (6.3–9.8) | 6.2 (6.2–11.9) | 0.36 |

| 82 | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 1.1(0.7–1.6) | 0.4(0.3–0.7) | 6.4 (6.0–6.9) | 7.2 (5.6–13.9) | 6.7 (6.2–12.7) | 0.34 |

| 82sb | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 4.2(2.1–8.5) | 1.8(0.8–3.9) | 7.5 (6.2–12.2) | 7.6 (6.0–13.3) | 6.0 (0.7–13.6) | 0.12 |

| 83 | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 1.6(1.1–2.1) | 0.7(0.5–1.0) | 7.1 (6.3–8.5) | 6.9 (6.2–13.6) | 6.1 (6.0–6.7) | 0.53 |

| 84 | 5.2 (4.6–5.8) | 2.7 (2.2–3.2) | 5.6 (4.9–6.4) | 0.9(0.8–1.1) | 0.5(0.4–0.6) | 6.9 (6.5–8.0) | 7.8 (6.4–15.3) | 6.5 (6.3–7.6) | 0.003 |

| 89 | 5.6 (5.0–6.3) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 4.5 (3.8–5.2) | 1.3(1.0–1.5) | 0.6(0.5–0.8) | 6.7 (6.4–7.3) | 6.9 (6.2–8.8) | 7.0 (6.6–9.2) | 0.16 |

| 4vHPVc | 10.3 (9.4–11.4) | 6.1 (5.4–6.9) | 8.2 (7.3–9.3) | 1.3(1.1–1.5) | 0.7(0.6–0.9) | 6.5 (6.3–6.8) | 6.7 (6.4–7.6) | 6.5 (6.4–6.9) | 0.002 |

| 9vHPVd | 16.6 (15.2–18.1) | 9.1 (8.1–10.1) | 12.8 (11.5–14.2) | 1.3(1.1–1.5) | 0.7(0.6–0.8) | 6.6 (6.4–6.8) | 6.9 (6.6–7.8) | 6.4 (6.3–6.5) | <0.0001 |

Note: IR= Incidence Rates per 1000 person-months, IRR= incidence rate ratios, 95% CI= 95% Confidence Intervals, HR= High Risk HPV types, LR= Low Risk HPV types. Values in bold denote statistical significance.

P values for grouped infections and type-specific infections were derived from Kaplan–Meier curves of HPV infection clearance comparing the three countries across the entire follow-up period. Values in bold denote statistical significance.

HPV 82 subtype IS39

4vHPV: one or more of the 4-valent HPV vaccine types (6, 11, 16,18)

9vHPV: one or more of the 4-valent HPV vaccine types (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58)

Clearance

Significant country differences in median duration of genital HPV infections (time to clearance) were observed for all grouped infections (any HPV, LR-HPV, HR-HPV, 4vHPV, and 9vHPV) with an overall trend of Brazil and the US having lower median infection duration compared to Mexico (Table 5). HPV16 infection median duration was slightly longer in Brazil compared to Mexico and the US (p=0.04). While HPV6 infection median duration was slightly longer in the US compared to Brazil and Mexico (p=0.03). There were no statically significant differences in median infection duration for HPV11 between the three countries (p=0.17).

Discussion

In this multinational cohort of 4085 men followed for a median of 48 months, we compared the natural history of genital HPV infection between the three countries: Brazil, Mexico, and US. The prevalence and incidence of the genital HPV types known to cause disease in males (16 and 6) was significantly higher among men from Brazil than men from Mexico. Prevalence and incidence of those genital HPV types in the US varied between being comparable to those of Mexico or Brazil. While genital HPV16 duration was significantly longer in Brazil (p=0.04) compared to Mexico and the US, HPV6 duration was shortest in Brazil (p=0.03) compared to Mexico and the US. Genital HPV infection prevalence, incidence and duration of the infection as well as risk factors associated with the prevalence of HPV significantly differed by country.

In a 2006 systematic review of the literature, there were 40 studies worldwide that evaluated the prevalence of male genital HPV (14). Overall HPV prevalence ranged from 1.3 to 72.9% with the majority of studies reporting ≥20%. We found that the prevalence of any genital HPV type was 60.2%, 49.2%, and 46.9% among men from Brazil, Mexico, and the US, respectively. The differences in prevalence between studies and countries may be due to sampling methods and processing, and the HPV genotyping method used in which a varying number of HPV genotypes are detected. In our study, we assessed the prevalence of 37 HPV genotypes and categorized “any HPV” as being positive for one more of those 37 types where other studies categorized “any HPV” based on being positive to one or more of two HPV types (HPV6 or 16) or 25 different HPV genotypes (14). Assessing genotype specific prevalence and incidence removes the limitation of using different HPV genotyping platforms. In the HIM Study HPV16 prevalence was 9.2%, 5.6%, and 8.4% in Brazil, Mexico and the US, respectively. HPV6 prevalence in the HIM Study was 6.7%, 6.1%, and 6.0% in Brazil, Mexico and the US, respectively. In the licensing trial for 4vHPV in males, prevalence of genital HPV6 was 3.4% overall and 3.9% in North America and 3.3% in Latin America (15). HPV16 prevalence was 3.8% overall and 4.5% in North America and 3.9% in Latin America (15). The men participating in the licensing trial were young (16–24 years old), heterosexual, and had between 1–5 female lifetime sexual partners (15) where men in the HIM Study had a wide age range, all sexualities, and a larger range in the number of sexual partners. These differences in demographic and sexual characteristics may explain why the country specific prevalence of HPV6 and 16 is so much higher among men in the HIM Study compared to the licensing trial for 4vHPV, given that the sampling methods and HPV genotyping methods were similar between the two studies.

Several factors associated with HPV prevalence differed by country of residence. As expected, we found that increasing number of female sexual partners was associated with higher HPV prevalence in all three countries. In Brazil, higher HPV prevalence was also significantly associated with being divorced/separated/widowed compared to single. Mexico and the US saw a similar trend of increasing HPV prevalence in the “recently single” group; however, this variable was not retained in the final multivariable model. “Recently single” men were likely exposed to new HPV types after ending a relationship. In Mexico and the US, MSM and virgins had a significantly higher prevalence of HPV compared to MSW, while a similar non-significant trend with MSM was observed in Brazil. We previously reported that the prevalence of genital HPV was similar between MSM and MSW (22); however, these proportions were not stratified by country of residence as presented here. Interestingly, virgins had a higher prevalence of HPV than did MSW in Mexico and the US. We recently reported the prevalence and factors associated with HPV among virgins (23). That study found that 25% of virgins had at least one HPV type detected and are likely acquiring HPV through non-penetrative sexual contact (23). In the US, not being circumcised was associated with a lower prevalence of HPV even after adjusting for potential confounders. Uncircumcised US males in the HIM Study were more likely to be Asian or other race, and have fewer number of female sexual partners. When race was forced back into the model for US, circumcision status was no longer significantly associated with genital HPV.

Similar to genital HPV prevalence, HPV incidence varied by country as well. The incidence rate for any HPV at the genitals was, 51.8, 25.0, and 35.7 per 100 person years (py) among men from Brazil, Mexico, and the US, respectively. These are similar to estimates provided in a 2016 systematic review of genital HPV incidence and duration (13) which reports incidence rates of any HPV from 14.8 per 100py among men from Mexico (24) to 46.1 per 100py among men from the US (25). Reported duration of any HPV type infection in the HIM Study (range 6.5–7.0 months) was also comparable to estimates provided in the systematic review by country with duration ranging from 5.1–5.9 months (13, 24, 25). The slight variation in duration is likely an arbitrary determent that is based on time between study visits in each cohort. The majority of men were able to clear their HPV infections within the 6-month time period.

Differences in the genital HPV natural history by country may explain the differences in HPV-related disease outcomes that we and other have observed (11, 26). Within the HIM Study, the incidence of genital warts was similar across the three countries, but the incidence of penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN) was higher in Brazil than Mexico and the US, although not statistically significant (26). In this study, we observed Brazil to have the highest prevalence and duration of HPV16 infections, which likely explains the higher rate of infection progression to disease (PeIN). When we assessed the progression of HPV6 infections to HPV6-positive genital warts, we found that Mexico and the US had higher progression rates of infection than men in Brazil. Although men in Mexico and US have a lower prevalence and incidence of HPV6 infections, they may be more likely to progress to disease (26). Differences in HPV progression may be due to host or viral differences in each country. We have previously shown that natural immunity to HPV does not prevent genital warts in men so antibody prevalence is not likely the reason for these country differences (27).

This study has several strengths including the large sample size, duration of follow-up, and data collection from three international clinical sites. Data collection and specimen processing was consistent across the three clinical sites. Men were recruited into the HIM Study at a time when HPV vaccination rates were low among females, and only young females were being vaccinated in the United States. Therefore, the prevalence estimates provided by country and age group reflect pre-vaccination estimates among males, uncontaminated by herd protection. The HIM Study is not a population-based study, but the demographics of the men included at each clinical site are similar to the underlying population of men aged 18–70 years in their respective communities (17). Therefore, a potential limitation of the cohort is that the findings may not be generalizable to all men in each country; although, our country specific data was comparable to findings from others in those specific countries (13, 14). HPV incidence and infection duration was based on clinic visits that occurred every six-months and may not accurately reflect the exact timing of infection or clearance of the infection. However, given the sample size and duration of follow-up, the six-month visit timing is cost-effective and still able to capture the natural history of HPV.

In summary, we found that genital HPV natural history differs in the three countries: Brazil, Mexico and the United States. In general, Brazil had a higher prevalence, incidence and duration of HPV16 and 6, which are the two predominant types known to cause disease in males compared to men from Mexico and HPV infection in the US varied between being comparable to those of Mexico or Brazil. Currently there is no routine screening for genital HPV among males and while HPV is common in men, and most naturally clear the infection, a proportion of men do develop HPV-related diseases. The 4vHPV and 9vHPV vaccines are licensed for the use in males and clinical trials have shown clinical efficacy in preventing disease (28). Globally, only five countries have national gender-neutral vaccine policies: the U.S., Austria, Australia, Israel, and some provinces in Canada. Results presented here indicate that men in Brazil and Mexico often have similar, if not higher HPV infections, compared to men from the U.S., and may benefit from similar policy measures.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The HIM Study infrastructure is supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health [R01 CA098803 to A.R.G.]. Merck provided financial support for the data analysis.

This research was supported in part by research funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

Special thanks to the men who provided personal information and biological specimens for the study. Thanks to the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study Team in São Paulo, Cuernavaca, and Tampa: Lenice Galan, Elimar Gomes, Elisa Brito, Filomena Cernicchiaro, Rubens Matsuo, Vera Souza, Ricardo Cintra, Ricardo Cunha, Birgit Fietzek, Raquel Hessel, Viviane Relvas, Fernanda Silva, Juliana Antunes, Graças Ribeiro, Roberta Bocalon, Rosária Otero, Rossana Terreri, Sandra Araujo, Meire Ishibashi, the Centro de Referência e Treinamento em Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis/AIDS nursing team, Aurelio Cruz, Pilar Hernandez, Griselda Diaz Garcia, Oscar Rojas Juarez, Rossane del Carmen Gonzales Sosa, Rene de Jesus Alvear Vazquez, Christine Gage, Kathy Cabrera, Nadia Lambermont, Kayoko Kennedy, Kim Isaacs-Soriano, Andrea Bobanic, Bradley Sirak, and Ray Viscidi (HIM Study Coinvestigator, Johns Hopkins). This work has been supported in part by the Biostatistics Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute; an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

Footnotes

Presentation in part: 31st International Papillomavirus Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, March 2017.

Conflicts of Interest: A.R.G., L.L.V., and E.L.P. are members of the Merck Advisory Board. S.L.S. received a grant (IISP53280) from Merck Investigator Initiated Studies Program. No conflicts of interest were declared for any of the remaining authors.

References

- 1.de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. The lancet oncology. 2012;13:607–15. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bruni L, et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl 5):F12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giuliano AR, Nyitray AG, Kreimer AR, Pierce Campbell CM, Goodman MT, Sudenga SL, et al. EUROGIN 2014 roadmap: Differences in human papillomavirus infection natural history, transmission and human papillomavirus-related cancer incidence by gender and anatomic site of infection. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2015;136:2752–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacey CJ, Lowndes CM, Shah KV. Chapter 4: Burden and management of non-cancerous HPV-related conditions: HPV-6/11 disease. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 3):S3/35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demeter LM, Stoler MH, Bonnez W, Corey L, Pappas P, Strussenberg J, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical presentation and an analysis of the physical state of human papillomavirus DNA. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1993;168:38–46. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin MA, Kleter B, Zhou M, Ayala G, Cubilla AL, Quint WG, et al. Detection and typing of human papillomavirus DNA in penile carcinoma: evidence for multiple independent pathways of penile carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1211–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wieland U, Jurk S, Weissenborn S, Krieg T, Pfister H, Ritzkowsky A. Erythroplasia of queyrat: coinfection with cutaneous carcinogenic human papillomavirus type 8 and genital papillomaviruses in a carcinoma in situ. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:396–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingles DJ, Pierce Campbell CM, Messina JA, Stoler MH, Lin HY, Fulp WJ, et al. HPV Genotype- and Age-specific Analyses of External Genital Lesions Among Men in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djajadiningrat RS, Jordanova ES, Kroon BK, van Werkhoven E, de Jong J, Pronk DT, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence in invasive penile cancer and association with clinical outcome. The Journal of urology. 2015;193:526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heideman DA, Waterboer T, Pawlita M, Delis-van Diemen P, Nindl I, Leijte JA, et al. Human papillomavirus-16 is the predominant type etiologically involved in penile squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4550–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alemany L, Cubilla A, Halec G, Kasamatsu E, Quirós B, Masferrer E, et al. Penile Cancer: Role of Human Papillomavirus in Penile Carcinomas Worldwide. European urology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Insinga RP, Dasbach EJ, Elbasha EH. Assessing the annual economic burden of preventing and treating anogenital human papillomavirus-related disease in the US: analytic framework and review of the literature. PharmacoEconomics. 2005;23:1107–22. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor S, Bunge E, Bakker M, Castellsague X. The incidence, clearance and persistence of non-cervical human papillomavirus infections: a systematic review of the literature. BMC infectious diseases. 2016;16:293. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1633-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunne EF, Nielson CM, Stone KM, Markowitz LE, Giuliano AR. Prevalence of HPV infection among men: A systematic review of the literature. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2006;194:1044–57. doi: 10.1086/507432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vardas E, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, Palefsky JM, Moreira ED, Jr, Penny ME, et al. External genital human papillomavirus prevalence and associated factors among heterosexual men on 5 continents. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;203:58–65. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa LL, Flores R, Salmeron J, Lee JH, et al. The human papillomavirus infection in men study: human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution among men residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2008;17:2036–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giuliano AR, Lee JH, Fulp W, Villa LL, Lazcano E, Papenfuss MR, et al. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:932–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by using L1 consensus PCR products by a single-hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1998;36:3020–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3020-3027.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–2. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ying Z, Wei LJ. The Kaplan-Meier estimate for dependent failure time observations. Journal of Multivariate Analyses. 1994;50:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1989;84:1074–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyitray AG, da Silva RJ, Baggio ML, Lu B, Smith D, Abrahamsen M, et al. The prevalence of genital HPV and factors associated with oncogenic HPV among men having sex with men and men having sex with women and men: The HIM study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38:932–40. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822154f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Nyitray AG, Hwang LY, Swartz MD, Abrahamsen M, Lazcano-Ponce E, et al. Human Papillomavirus Prevalence Among 88 Male Virgins Residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2016;214:1188–91. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales R, Parada R, Giuliano AR, Cruz A, Castellsague X, Salmeron J, et al. HPV in female partners increases risk of incident HPV infection acquisition in heterosexual men in rural central Mexico. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2012;21:1956–65. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giuliano AR, Lu B, Nielson CM, Flores R, Papenfuss MR, Lee JH, et al. Age-specific prevalence, incidence, and duration of human papillomavirus infections in a cohort of 290 US men. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008;198:827–35. doi: 10.1086/591095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudenga SL, Torres BN, Fulp W, Silva R, Villa LL, Lazcano Ponce E, et al. EUROGIN. Salzburg, Austria: 2016. Country Specific HPV-related Genital Lesions Among Men Residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States: HIM Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sudenga SL, Viscidi RP, Torres BN, Lin HY, Villa L, lazcano-Ponce E, et al. Natural immunity to Human papillomavirus (HPV) does not protect against incident external genital lesions in men: the HPV infection in men study. International Papillomavirus Conference; Lisbon, Portugal. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, Moreira ED, Jr, Penny ME, Aranda C, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV Infection and disease in males. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:401–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]