Young people with chronic conditions often face more difficulties negotiating the tasks of adolescence than their healthy peers. National, population based studies from Western countries show that 20-30% of teenagers have a chronic illness, defined as one that lasts longer than six months. However, 10-13% of teenagers report having a chronic condition that substantially limits their daily life or requires extended periods of care and supervision.

Table 1.

Prevalence (per 1000 adolescents aged 12-18 years) of certain chronic conditions in mid-adolescence

| Prevalence | |

|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal conditions: | 41 |

| Cerebral palsy | 15 |

| Skin conditions | 32 |

| Serious mental health problems: | 120* |

| Anorexia or bulimia nervosa | 15 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 100* |

| Diabetes: | |

| Type 1 | 2 |

| Type 2 | 1-2 |

| Respiratory conditions: | 150* |

| Asthma | 100* |

| Cystic fibrosis | 0.1 |

| Epilepsy | 4 |

| Ear or hearing problems | 18 |

Uncertain value owing to differences in disease definitions

The burden of chronic conditions in adolescence is increasing as larger numbers of chronically ill children survive beyond the age of 10. Over 85% of children with congenital or chronic conditions now survive into adolescence, and conditions once seen only in young children are now seen beyond childhood and adolescence. In addition, the prevalence of certain chronic illnesses in adolescence, such as diabetes (types 1 and 2) and asthma, has increased, as has survival from cancer.

Impact of chronic conditions on adolescence

Chronic conditions in adolescence can affect physical, cognitive, social, and emotional spheres of development for adolescents, with repercussions for siblings and parents too.

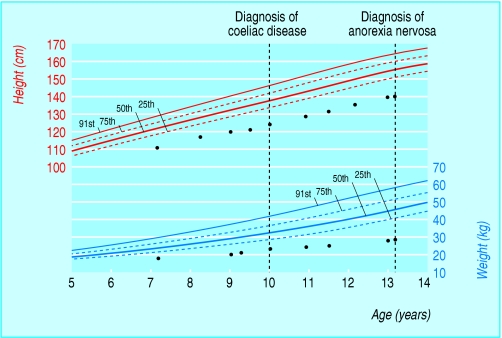

Figure 1.

Growth chart (with 25th, 50th, 75th, and 91st centiles) of 13 year old girl with coeliac disease and anorexia nervosa. Coeliac disease was diagnosed at age 10 during investigation for short stature. She later presented, at age 13, with mother's concerns about restriction of food

Physical effects

Common sequelae of chronic illness and its treatment include short stature and pubertal delay. Undernutrition is common in many chronic conditions, and obesity can result from conditions that limit physical activity. Visible signs of illness or its treatment mark young people out as different at a time when such differences are important to young people and their peers. Body image issues related to height, weight, pubertal stage, and scarring can contribute to reduced self esteem and negative self image, problems that may persist into adult life.

Emotional and mental health

Many young people cope well with the emotional aspects of having a chronic illness. Chronically ill young people are more likely, however, to have a lower level of emotional wellbeing than their healthy peers. Young people often report a sense of alienation from their peers and frustration with the requirements of managing their condition and negotiating the healthcare system.

Table 2.

Features of depression in adolescence

| • Low mood and tearfulness |

| • Moodiness and emotional outbursts |

| • Boredom |

| • Withdrawal and isolation |

| • Feelings of hopelessness and helplessness |

| • Changes in appetite and eating behaviour |

| • Disturbed sleep (such as greatly increased sleep and early or frequent waking) |

| • Fatigue |

| • Highly impulsive behaviour, risk taking behaviour (such as alcohol misuse, crime) |

| • Psychosomatic symptoms |

| • Poor school performance |

| • Preoccupation with death (in the media, clothing, art, music) |

| • Suicidal ideation |

| • Decrease in treatment adherence or in interest in managing their health |

Young people with chronic illness do not have an increased rate of mental illness, as is the case in adults with chronic illness. However, because those with chronic illness experience many sources of stress, health professionals must be alert for depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorders both in young people and in their families. Behavioural problems and declining school performance can be specific markers of underlying psychological distress in adolescence.

Social, educational, and vocational aspects

Effects of chronic illness on cognition and learning can be subtle, often manifesting as poor performance at school—largely the result of repeated absence because of poor health or admission to hospital. Young people with chronic illness are at greater risk of social isolation owing to school absenteeism and lack of participation in recreational and sporting activities. Together with educational disadvantage, this means that young people with chronic conditions may find great difficulty getting jobs and achieving financial independence as adults.

Figure 2.

Young people with a chronic condition who can take part in recreational and sporting activities with their peers may be less likely to be socially isolated

Health professionals must help to improve young people's transition from education to the workforce. They can do this in several ways. They should encourage development of vocational capacity in the same way as for healthy young people: encouraging employment in part time jobs and working for parents; identifying suitable work experience placements; and identifying strengths and abilities rather than disabilities. They should start these strategies in early adolescence. Health professionals should also continually reassess the young person's vocational readiness in terms of educational achievement, communication skills, self esteem, expectations, and work experience.

Table 3.

Effect of adolescence on chronic illness

| • The developmental changes of adolescence will reciprocally affect chronic illness and its management |

| • Smoking can exacerbate health outcomes in young people with asthma, cystic fibrosis, and diabetes |

| • Alcohol and dance parties can complicate diabetes care |

| • Exhaustion from late night parties can lead to unstable epilepsy |

| • For physiological reasons certain diseases can become more unstable during adolescence (the hormonal changes of the pubertal growth spurt decrease insulin sensitivity and make diabetes more difficult to control; lung function often deteriorates during adolescence in those with cystic fibrosis, especially girls) |

Impact of chronic conditions on families

Normal parenting issues in adolescence are amplified by chronic conditions. Chronic illness can hinder the young person's progression towards autonomy, keeping them dependent on their parents just when they are needing more independence. Additional time is needed to care for the young person, which generally carries a financial burden. It is not uncommon for parents to experience guilt, frustration, anxiety, and depression. Specific support services can be useful, and family therapy may be helpful. Siblings are also at greater risk of adjustment difficulties as they often miss out on parental time and attention and may be excluded from family discussions.

Figure 3.

Treatment: adherence and concordance

Health professionals aim to achieve the best treatment of the condition, often resulting in a focus on future benefit from current behaviour. In contrast, young people are influenced by the “here and now” and are more interested in achieving the goals of adolescence than improving their health. This can lead to conflicting priorities between the young person and his or her health professionals (and parents).

Health professionals can make the treatment goals more relevant for the young person by identifying how the illness affects them in terms of their appearance, ability to socialise well, or recreational opportunities. The task for health professionals is to work with the young person to develop concrete short term goals (weeks to months), such as focusing on good enough health to attend the school camp in four to six weeks' time. Active participation in negotiation of treatment plans helps young people to take back some ownership and control of the disease from the parents. Adolescents should have an understanding of their illness, especially the rationale for treatment and treatment options. Information must be provided at a level that is developmentally and cognitively appropriate.

Table 4.

Improving treatment adherence in adolescents

| • See the young person alone and discuss confidentiality |

| • Use a non-judgmental approach and ask open ended questions |

| • When asking about medication use, indicate to the young person that poor adherence to treatment is normal behaviour |

| • Explore what the young person knows about health and correct any misunderstandings |

| • Educate the young person about his or her illness and treatment |

| • Negotiate short term treatment goals |

| • Use the simplest regimen |

| • Tailor the regimen to the young person's daily routines |

| • Identify and discuss any potential barriers to adherence |

| • Explain the treatment regimen and repeat the instructions |

| • Give written instructions |

| • Avoid jargon in oral and written instructions |

| • Suggest reminders—for example, stickers on the bathroom mirror, medication calendar |

| • Enlist the support of parents, significant adults, trusted peers |

| • Review treatment and monitor adherence frequently—give useful feedback |

Families can be a major source of support around adherence to treatment. Young people who come from cohesive families with open communication channels and lower levels of stress adhere better to treatment regimens and have better long term health outcomes. Trusted peers may also be involved as positive sources of support.

Efforts to improve adherence should be routine in all consultations with young people. After hearing the parental perspective, seeing the young person alone for part of the consultation is important. A non-judgmental approach that accepts that poor adherence is relatively normal behaviour encourages the young person to be more honest when reporting less than ideal behaviour (for example, “Most people I see your age have difficulty taking medication regularly. Tell me, how are things going with you? Are you more likely to forget your morning or evening medication?”). Specifically inquire about adherence to each aspect of their healthcare regimen.

Table 5.

Importance of routine in adherence

| • A routine—or the lack of one—can affect adherence in young people, who often have a routine for one dose or treatment but not for another |

| • An example of an evening routine resulting in good adherence may include cleaning their teeth, setting their alarm clock, and then taking their medication |

| • The lack of morning routines around medication is common—often related to rushing before school |

| • Tailor their treatment regimens to make them as simple as possible |

| • Regular review provides an opportunity to remind the young person of how they can better monitor their health or adhere to their medication regimen, even in a small way |

Primary care

The normal primary healthcare needs of those with chronic illness are often neglected. The general practitioner is a key link with schools and community agencies. The general practitioner's knowledge of the family means they can offer support to parents and siblings alike. Health promotion should not be forgotten, whether it relates to nutrition, sexual health, or health risk behaviours such as smoking and drinking.

Transition to adult services

Young people who need ongoing specialist care beyond adolescence must transfer to adult services. How the transfer takes place can depend on the availability of local services and the extent of specialist involvement. The care can be transferred, for example, from a specialist paediatric service either direct to an adult service or via an adolescent or young adult service (which may be located within either the paediatric or the adult service). The general practitioner can provide an important source of continuity during the change between specialty practitioners (including, for example, liaison with occupational therapists and physiotherapists), although this can be difficult in some highly specialised chronic illnesses.

Table 6.

Key points for transition from paediatric services to adult services

| • Transition preparation is an essential component of high quality health care in adolescence |

| • Every paediatric general and specialty clinic should have a transition policy; more formal transition programmes are needed if large numbers of young people are being transferred to adult care |

| • Young people should not be transferred to adult services until they have the skills to function in an adult service and have finished growth and puberty |

| • Preparation for transition should start early—well before entering adolescence |

| • Personalised transition plans are needed for each young person |

| • An identified person (ideally a nurse specialist) in the paediatric and adult teams must be responsible for transition arrangements |

| • Management links must be developed between the two services |

| • Transition arrangements should be evaluated |

Young people and their parents need information about the transition process and time to prepare. Parental anxieties that the adult team will not be able to cater for their teenager's healthcare needs are a common barrier to successful transition. Good communication between the paediatric and adult healthcare teams is important for smooth transition.

Transfer should take place when young people are developmentally ready and have the necessary set of skills to cope well in adult services, rather than at a fixed age. Primary care can play its part in promoting a smooth transition by encouraging independence in consultations with young people—for example, by seeing young people by themselves as well as with their parents—and beginning this process in early adolescence.

The transfer of an adolescent from child centred to adult oriented healthcare systems is an important transition and one that is more complex than the simple transfer of the medical record from one institution or doctor to another

Adolescents with chronic illness have the same developmental needs as their healthy peers. Attention must be paid to developmental outcomes if good health outcomes are to be achieved

The photograph of the disabled girl taking part in sport was supplied by the authors.

The ABC of adolescence is edited by Russell Viner, consultant in adolescent medicine at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Trust (rviner@ich.ucl.ac.uk). The series will be published as a book in summer 2005.

Competing interests: None declared.

Further reading and resources

- • Neinstein LS. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

- • Suris JC, Michaud PA, Viner R. The adolescent with a chronic condition: parts 1 and 2. Arch Dis Child 2004;89: 938-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • www.connexions.gov.uk (for vocational advice for young people)

- • www.skill.org.uk (the UK National Bureau for Students With Disabilities, which promotes opportunities for young people with disability in further education, training, and employment)

- • www.euteach.com (for resources for teaching about chronic illness in adolescent health)