Abstract

Purpose: Gastric cancer (GC), one of the world's top five most common cancers, is the third leading cause of cancer related death. It is urgent to identify non-invasive biomarkers for GC. The objective of our study was to find out non-invasive biomarkers for early detection and surveillance of GC based on glycomic analysis.

Method: Ethyl esterification derivatization combined with MALDI-TOF MS analysis was employed for the comprehensive serum glycomic analysis in order to investigate glycan markers that would indicate the onset and progression of gastric cancer. Upon the discovery of the candidate biomarkers, those with great potential were further validated in an independent test set. Peaks were acquired by the software of MALDI-MS sample acquisition and processing and analyzed by the software of Progenesis MALDI.

Results: The differences in glycosylation were found between non-cancer controls and gastric cancer samples: hybrid and multi-branched type (tri-, tetra-antennnary glycans) N-glycans were increased in GC, yet monoantennary, galactose, bisecting type and core fucose N-glycans were decreased. In training set, core fucose (AUC=0.923, 95%CI: 0.8485 to 0.9967) played an excellent diagnostic performance for the early detection of gastric cancer. The diagnostic potential of core fucose was further validated in an independent cohort (AUC=0.854, 95%CI: 0.7592 to 0.9483). Besides, several individual glycan structures reached both statistical criteria (p-values less than 0.05 and AUC scores that were at least moderately accurate) when comparing different stages of GC samples.

Conclusion: We comprehensively evaluate the serum glycan changes in different stages of GC patients including peritoneal metastasis for the first time. We determined several N-glycan biomarkers, some of these have potential in distinguishing the early stage GC from healthy controls, and the others can help to monitor the progression of GC. The findings also enhance understanding of gastric cancer.

Keywords: gastric cancer, glycomic analysis, biomarker, MALDI-TOF-MS, peritoneal metastasis gastric cancer.

Introduction

Although the incidence of gastric cancer (GC) has declined markedly over the past few years, it still remains the fifth most common malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer related death in both sexes worldwide 1, 2. In order to reduce the incidence and mortality of GC, three levels of prevention strategies have been proposed 3. In order to decrease the GC-related incidence, primary prevention strategies have been used to prevent the exposure of GC risk factors, such as bad lifestyle or Helicobacter pylori infection. Secondary and Tertiary prevention strategies which attach great importance to clinical practice have an effect on decreasing GC-related mortality. Secondary prevention strategies are mainly focused on detecting and treating GC in early stage. Endoscopy is an accurate invasive tool in the diagnosis of early stage GC, however, this procedure is limited by cost, risks of complications and discomfort for the patients. Furthermore, asymptomatic patients generally not select endoscopic for further investigation 4, 5. Tertiary prevention aims to control the symptoms and progression of established cancer. Noteworthy, peritoneal metastasis gastric cancer (PMGC) is the most prevalent GC distant metastasis, which is an urgent issue for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment 6. Therefore, the early detection and disease surveillance are important for GC. Although H.pylori eradication and endoscopy were employed to prevention GC, non-invasive screening tools are urgently needed according to the GC prevention strategies 7.

Serological glycomic profiling is an emerging non-invasive screening tool for finding potential biomarkers in diagnosis of early stage cancer and disease surveillance. Serum glycans alteration plays an important role in regulating the proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis of tumor 8. Some of them have also been recognized as potential biomarkers in numerous kinds of cancers, including pancreatic cancer 9, ovarian cancer 10, prostate cancer 11 and hepatocellular carcinoma 12. To date, glycan alterations in gastric cancer only have been systematically reported in very few studies. Bones. et al detected 20 kinds of glycans in total and immunoaffinity depleted serum and identified the increases in the levels of sialyl Lewis X epitopes (SLeX) present on triantennary glycans in gastric cancer 4. Additionally, Liu. et al identified 9 N-glycan structures (peaks) and the levels of core fucose residues were significantly decreased in GC using DSA-FACE technology 13. In those previously published articles, the number of identified N-glycans was limited due to insufficient sensitivity of the methods, which could not provide comprehensive glycomic analysis in GC. Meanwhile, the majority of previous studies focused on investigating the glycan alterations between gastric cancer patients and non-cancer controls. Glycan alterations across gastric cancer development and progress have been rarely reported simultaneously, which could provide not only a more comprehensive understanding of the N-linked glycan biomarkers for early GC diagnosis and subsequent cancer surveillance but also insights into underlies mechanism of GC development.

Mass spectrometry is the emerging powerful technology for analyzing glycan structures, offering an alternative for glycosylation identification due to its high sensitivity 9. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), particularly, is being developed as a platform for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of glycans due to its high sensitivity and easiness of operation 14. Due to the negative charge of the sialic acids in the positive MALDI-TOF MS mode and the preferential cleavage of the sialic acids' labile nature, derivatization of sialic acid is necessary. Commonly used derivatization is permethylation 15, which can stabilize sialic acid as well as increase sensitivity of MS analysis. However, this method often brings byproducts and shows no complete derivatization 16. In this study, ethyl esterification method was employed to enabled sialylated structures to be protected and ensured reliable detection of serum N-glycan profiles 17. Therefore, ethyl esterification derivatization combined with high sensititive MS analysis was employed for glycan analysis in this work, which allowed comprehensive identification of GC N-glycome.

In this study, more than 80 different N-glycans were detected from GC patient serum. The number of detected N-glycans was much more than that in previous glycomic studies of gastric cancer 4, 13, 18, 19, 20, 21 providing a rich source of information for glycan alteration analysis of the disease process 22.

Here, we obtained N-glycan profiles derived from 10-μL serum sample aliquots using MALDI-TOF MS that have potential to indicate GC progression. The results displayed statistically differences between non-cancer samples and gastric cancer samples, some of them could be potential biomarkers for GC early diagnose. Two independent cohorts were set up to discover and validate the great potential biomarkers. In addition, MS glycomic profiling allowed us to analyze several distinct N-glycans between the early stage (EGC), advanced (AGC) and peritoneal metastasis (PMGC) patients. Notably, N-glycomic analysis in peritoneal metastasis gastric cancer has been rarely reported, which is of great significance for finding potential biomarkers for differentiation the AGC from the PMGC, avoiding PMGC patients from unnecessary surgery. Therefore, this study is aimed at the discovery of non-invasive glycan biomarkers for detection and surveillance of gastric cancer by glycomics analysis based on MS method.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Milli-Q water (MQ) used in this study was generated from a Q-Gard 2 system (Millipore, Amsterdam, Netherlands), maintained at ≥18 MΩ. Ethanol, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), PBS (disodium hydrogen phosphate dihydrate (Na2HPO4 × 2H2O), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4) and sodium chloride (NaCl)) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) hydrate, sodium hydroxide, Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) hydrochloride were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Additional components used for this study included recombinant peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany), 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,5-DHB) from Bruker Daltonics (Bremen, Germany) and HPLC Supra Gradient acetonitrile (ACN) from Biosolve (Valkenswaard, Netherlands).

Study population and sample collection

The 203 serum samples were collected from Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University (163 GC samples) and Shanghai Cancer Center of Fudan University (40 non-cancer controls) (Shanghai, China). And the serum layer was collected and stored at -80 °C until analysis. No more than three cycles of freezing/thaw were allowed for any sample. Approvals were obtained from the Institutional Review Board at each study center and informed written consents from all participants were acquired.

Classical tumor markers detection

Clinical and biochemical data from the patients are summarized in Table 1. Tumor marker levels, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125) and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) were determined on a Roche E170 modular with matched reagents.

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of the participants

| Mean(min-max) or N0. % | Total: n=143 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-cancer: n=20 | EGC: n=31 | AGC: n=46 | PMGC: n=46 | |||

| Age, y | 66.45(51-87) | 60.90(45-79) | 59.48(40-84) | 59.54(32-81) | ||

| Male | 7(35%) | 24(77%) | 28(61%) | 27(59%) | 86 | |

| Female | 13(65%) | 7(33%) | 18(39%) | 19(41%) | 57 | |

| CEA | 1.66(1.02-4.25) | 2.98(0.20-25.10) | 4.74(0.50-55.90) | 16.49(0.40-372.80) | ||

| <5ng/mL | 20 | 27 | 36 | 34 | 117 | |

| ≥5ng/mL | 0 | 2 | 7 | 12 | 21 | |

| Absent | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 | |

| CA19-9 | 13.05(5.61-26.97) | 10.16(0.90-35.50) | 88.54(0.60-2501.00) | 600.36(0.60-10000.00) | ||

| <37U/mL | 20 | 29 | 39 | 26 | 114 | |

| ≥37U/mL | 0 | 0 | 6 | 17 | 23 | |

| Absent | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | |

| CA125 | 7.18(3.61-10.96) | 13.59(3.70-49.10) | 14.24(3.40-44.40) | 103.52(7.50-156.00) | ||

| <35U/mL | 13 | 18 | 33 | 21 | 85 | |

| ≥35U/mL | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 14 | |

| Absent | 7 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 44 | |

| AFP | 6.84(4.41-9.70) | 2.43(0.20-6.90) | 2.47(0.61-11.50) | 242.05(1.00-815.30) | ||

| <20ng/mL | 20 | 29 | 39 | 41 | 129 | |

| ≥20ng/mL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Absent | 0 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 13 | |

Glycomic analysis

Release of N-glycans from glycoproteins: N-glycans were released from the human serum glycoproteins according to the method described by Karli R. Reiding et al 17. Briefly, 10 μL sample was denatured by adding 20 μL of 2% SDS and incubating for 15 min at 65 °C. The N-glycan released steps proceed with adding 20 μL of release mixture which containing 0.5 mU PNGase F and 2% NP-40 in 5× PBS (10× PBS containing 57 g/L Na2HPO4 × 2H2O, 5 g/L KH2PO4 and 85 g/L NaCl) and incubating 24h at 37 °C.

Ethyl esterification of released glycans: The released glycan sample was added in to tubes filled with 200 μL freshly prepared derivatization reagent (250mM EDC and 250 mM HOBt in ethanol). Then the mixture was incubated for 3h at room temperature. Before purification, 200 μL ACN was added to the derived glycans and further incubated at -20°C for 15 min to precipitate the protein.

Sepharose HILIC SPE glycan enrichment: The 96-wells PVDF membrane plate filled with 50 μL sepharose beads (45-165 μm, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) was prewashed with 20% ethanol/H2O and solvent was removed by centrifuging 1 min at 1000rpm. Beads were wash three times with 200 μL of water and three times with 200 μL 95% ACN. Next, the samples were loaded to the plate, which was repeated twice. In order to facilitate binding, the plate was put on a multiwall plate shaker incubating 10 min at 380 rpm at room temperature before the solvent removed by centrifuge. The plate was subsequently washed twice with 95% ACN 0.1% TFA and 95% ACN respectively, after which 200 μL water was added for elution by centrifuging 1 min at 1000 rpm. Then the elute was freeze-dried in a freeze dryer over 24 hours and finally resolved in 20 μL water.

MALDI-TOF MS: Before MALDI-TOF MS serum glycomic analysis, TOFMix (LaserBio Laboratories, France) containing an eight-peptide calibration standard was used for external calibration of MS. 1 μL of collected N-glycan was spotted onto a MALDI target plate (800/384 MTP AnchorChip, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and allowed to dry by air. Then, 1μL 2,5-DHB (5 mg/ mL) 1 mM NaOH in 50% ACN was added onto the sample layer and allowed to dry by air, followed by recrystallized to form homogeneity of the spot surface with ethanol. Each sample was spotted in triplicate. The samples were test automatically in a “batch mode” by AXIMA Resonance MALDI-QIT-TOF MS (Shimadzu Corp. JP) equipped with a 337nm nitrogen laser in reflector positive ionization mode. The laser power was set as low as 100. The m/z range was monitored to range from 900 to 4000. Two laser shots were set to generate a profile, and 200 profiles were accumulated from different points of laser irradiation into one file for each sample spot.

Data processing and analysis and statistical analysis

The MALDI mass spectra data were pre-processed, normalized and extracted using the software of Progenesis MALDI. The following statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 and SPSS (version 16.0). The normalized volumes from Progenesis MALDI resulting data were aligned and normalized to facilitate identification of possible alterations in the levels of the glycans present. Notably, each serum sample was spotted in triplicate, therefore, three normalized spectra for each serum sample were averaged before statistical tests.

The “diagnostic potential” of glyco-subclasses and specific glycan structures were firstly performed by Student's t test using SPSS. In addition, results showing statistically significant p-values (less than 0.05) were further processed by the receiver-operator-characteristics (ROC) test and generate values of area-under-the-curve (AUC) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) using GraphPad Prism 5. If the AUC value was great than 0.9 that indicates a “highly accurate” test, while values between 0.8 and 0.9 were considered to be “accurate”. When the AUC value was between 0.7 and 0.8, the test was concluded to be “moderately accurate.” An “uninformative” test resulted in an AUC value that was between 0.5 and 0.7.

Results

Serum N-glycan profiles

The N-glycan profiles were examined by MALDI-MS in non-cancer individuals (n=20) and in patients with gastric cancer (n=123) including EGC (n=31), AGC (n=46) and PMGC (n=46). The demographic characteristics of the participants were presented in Table 1. The age and gender were matched between non-cancer participants and cancer patients as far as possible.

The typical glycomic profile from gastric cancers is shown in Supplementary Fig.S1, which is a representative MALDI mass spectrum for serum N-glycans. 81 N-glycans (peaks) were identified in all samples. The glycan structures and compositions were proposed based on their mass and tandem MS in previous literatures 17, 23 (Supplementary Table S1). The amounts of glycans detected in present study are nearly three times as much as that reported previously 13, 19, 20 thanks to high sensitivity methods by combining the efficient derivatization method with MALDI-TOF MS. Therefore, we obtained more comprehensive and reliable glycans information related to gastric cancer.

Glycosylation differences between non-cancer participants and gastric cancer patients

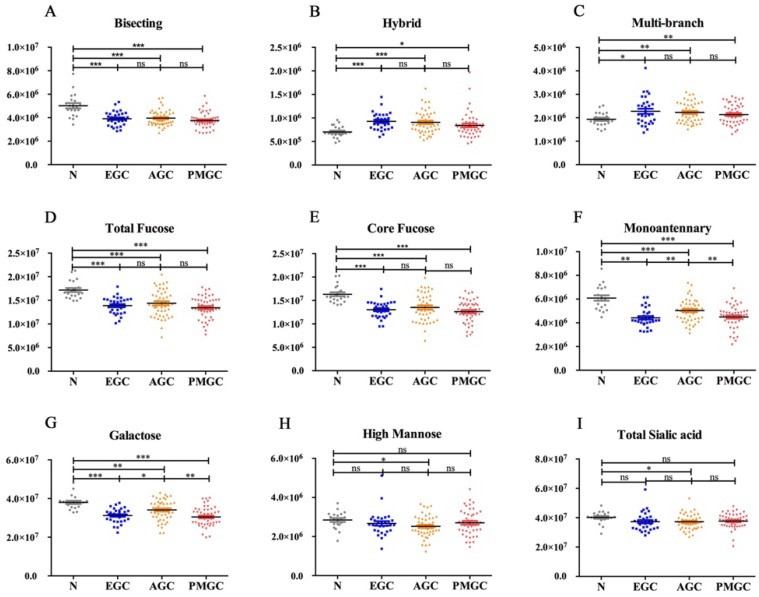

We quantified 81 peaks among the 4 groups and divided them into 8 glyco-subclasses based on their characteristic structural features: bisecting type N-glycans, hybrid, monoantennary, multi-branched type (tri-, tetra-antennnary glycans), galactose, total fucose, high mannose, total sialic acid (Fig.1) in order to determine the alternations of N-glycan in gastric cancer.

Fig 1.

The abundance of the nine representative glycan groups in different cancer stages and controls. The N-glycans were grouped according to their structural fetures: bisecting type N-glycans (A); hybrid (B); multi-branched type (tri-, tetra-antennnary glycans) (C); total fucose (D); core fucose (E); monoantennary (F); galatose (G); high mannose (H); total sialic acid (I).

In the study, hybrid N-glycans showed significantly increased levels in all three stages of gastric cancer compared with non-cancer participants (Fig.1B). To our knowledge, this result was reported for the first time. Similar increases in the levels of multi-branched type (tri-, tetra-antennnary glycans) were also observed (Fig. 1C). Differently, total bisecting type N-glycans (Fig. 1A), monoantennary N-glycans (Fig. 1F), galactose (Fig. 1G) and total fucose (Fig. 1D) showed decreased levels in gastric cancer compared with control. As both core fucose and arm fucose contribute to the amounts of total fucose, we compared the levels of core fucose (Fig. 1E) and arm fucose (data was not shown) between four groups. The result indicated that core fucose played a decisive role in alternation of total fucose. We also analyzed N-glycan profiles of total high mannose (Fig. 1H) and total sialic acid (Fig. 1I), the results showed no significant differences between non-cancer participants and cancer patients.

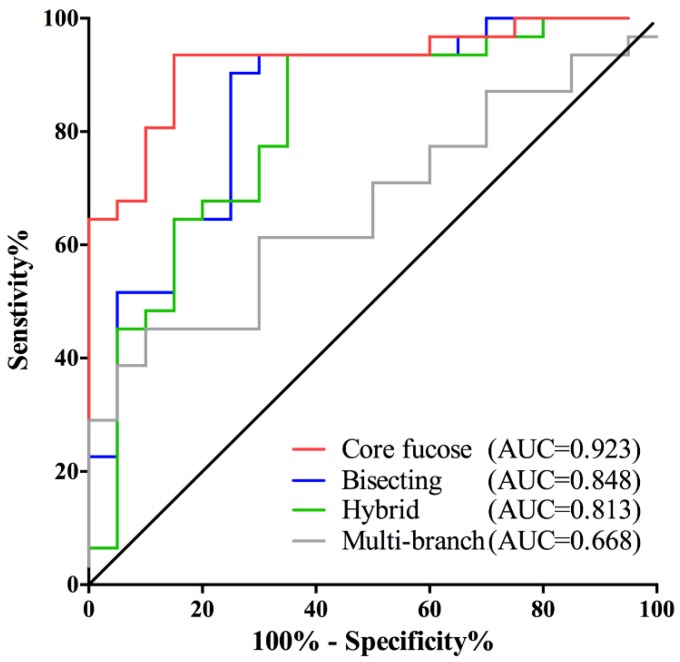

It is interesting to note that the changes in core fucose, bisecting, hybrid and multi-branched type glycans presented in the early stage of GC. And these four glyco-subclasses displayed no significant difference among EGC, AGC and PMGC. Thus, these glyco-subclasses could be used as potential early-detected biomarkers. The classification efficiency of the glyco-subclasses biomarkers was evaluated by AUC of receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves (Fig. 2). The AUC value of core fucose was 0.923 (95%CI: 0.8485 to 0.9967), making this glyco-subclass highly predictable for the early detection of gastric cancer. The glycol-subclass of bisecting type N-glycans demonstrated an AUC of 0.848 (95%CI: 0.7362 to 0.9606) and the glyco-subclass of hybrid type presented an AUC of 0.813 (95%CI: 0.6865 to 0.9393), suggesting an accurate diagnosis. An AUC value of multi-branched type was 0.668 (95%CI: 0.5210 to 0.8145), suggesting a lack of cancer determination for this glyco-subclass. The specificity and sensitivity of selected glyco-subclasses are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses for the prediction of early stage gastric cancer (EGC). The ROC was employed to evaluate the classification efficiency of these glyco-subclaaaes including core fucose, bisecting type N-glycan, hybrid and multi-branch. Their AUC values were 0.923, 0.848, 0.813, 0.668 respectively.

Glycosylation differences between different stages of gastric cancer

The nine glyco-subclasses were also compared among three GC stages in an attempt to further determine the alternations of N-glycan in the progression of disease. We found monoantennary and galactose displayed significant changes among four groups (Fig. 1). However, these two glyco-subclass could not accurately distinguish the three GC stages. Therefore, we analyzed the individual N-glycan abundance to obtain more valuable information to divide different stages.

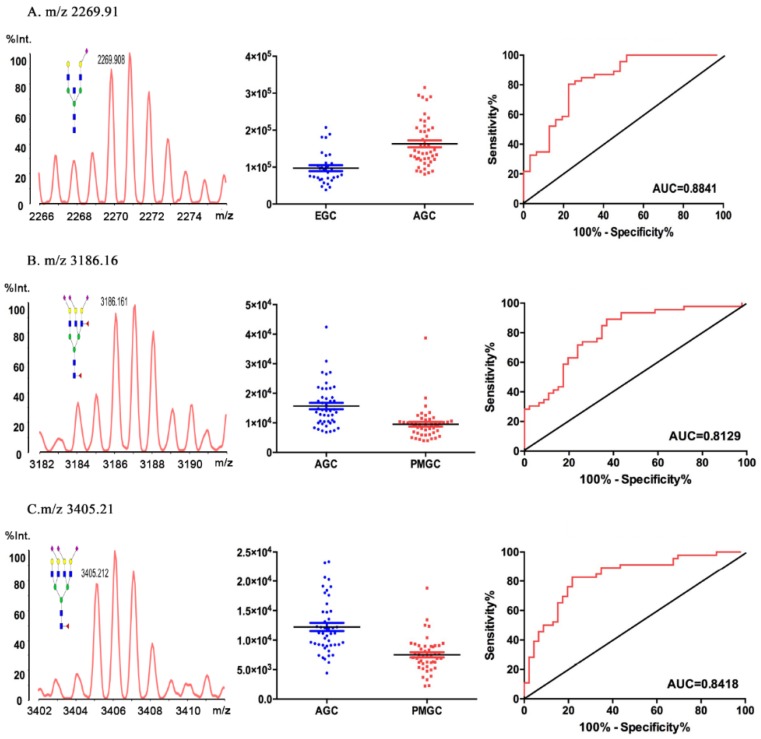

The results of the individual N-glycan structure abundance analysis between early and advanced gastric cancer showed that there were significant differences in 22 types of glycans (P<0.05) (Table 2). Data for eight glycans resulted moderately accurate AUC scores (AUC>0.7). And the N-glycan of m/z 2269.91 (H5N5E1AC2) demonstrated an AUC value of 0.884, making this particular structure accurately predict the disease state (Fig.3A). The result indicated that H5N5E1AC2 displayed a potential clinical utility to monitor the progression of gastric cancer.

Table 2.

List of the 22 serum N-glycans that were evaluated to be significantly different between Advanced GC and Early stage GC.

| m/z | Composition | P Value | P Value Summary | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 933.2999268 | H3N2 | 0.0112 | * | 0.6872 |

| 1257.440918 | H5N2 | 0.0003 | *** | 0.7412 |

| 1298.461548 | H4N3 | 0.0033 | ** | 0.6858 |

| 1444.494995 | H4N3F1 | 0.0089 | ** | 0.6725 |

| 1542.514648 | H3N5 | 0.0014 | ** | 0.7062 |

| 1617.601929 | H4N3E1 | 0.0019 | ** | 0.7027 |

| 1663.584106 | H5N4 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.763 |

| 1763.635376 | H4N3F1E1 | 0.0308 | * | 0.655 |

| 1936.703247 | H5N4L1 | 0.0341 | * | 0.6403 |

| 2023.78418 | H4N5E1 | 0.0002 | *** | 0.7489 |

| 2158.761475 | H5N5F2 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7945 |

| 2209.783447 | H5N4L2 | 0.0077 | ** | 0.6999 |

| 2227.793457 | H5N5E1Ac1 | 0.0028 | ** | 0.6802 |

| 2231.77832 | H6N6 | 0.0046 | ** | 0.7167 |

| 2269.907959 | H5N5E1Ac2 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.8289 |

| 2401.876953 | H5N4F1L1E1 | 0.0015 | ** | 0.6985 |

| 2429.927246 | H4N7E1 | 0.0008 | *** | 0.7132 |

| 2477.901855 | H5N5F2E1 | 0.0357 | * | 0.6522 |

| 2504.936523 | H5N5E2 | 0.0329 | * | 0.6508 |

| 2547.91748 | H5N4F2L1E1 | 0.0312 | * | 0.655 |

| 2574.913086 | H6N5L2 | 0.0287 | * | 0.6388 |

| 2604.955811 | H5N5F1L1E1 | 0.0495 | * | 0.6367 |

Fig 3.

Representative mass spectra, scatter plot analysis and ROC curve analysis for representative glycoform. The 2269.91 m/z was different in EGC and AGC (A). The 3186.16m/z (B) and 3405.21 m/z (C) were different in AGC and PMGC.

Based on the detrimental impact caused by peritoneal metastasis in gastric cancer, we compared the glycomic profiles in advanced gastric cancer and metastasis gastric cancer, 30 out of the 81 N-glycan peaks were statistically altered (P<0.05). The AUC values of 15 types glycans deemed to be moderately accurate (AUC>0.7) (Table 3). Comparing with advanced cancer group and peritoneal metastasis group, H6N5F2L2E1 (m/z 3186.16) (AUC=0.813, 95%CI: 0.7120 to 0.8920, P < 0.0001, Fig.3B) and H7N6F1L2E1 (m/z 3405.21) (AUC=0.842, 95%CI: 0.7469 to 0.9157, P < 0.0001, Fig.3C) displayed a potential clinical utility to monitor the gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer.

Table 3.

List of the 30 serum N-glycans that were evaluated to be significantly different between Metastasis GC and Advanced GC.

| m/z | Composition | P Value | P Value Summary | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1257.440918 | H5N2 | 0.0137 | * | 0.6508 |

| 1298.461548 | H4N3 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7202 |

| 1444.494995 | H4N3F1 | 0.0035 | ** | 0.6668 |

| 1455.511963 | H3N3E1 | 0.0083 | ** | 0.6545 |

| 1663.584106 | H5N4 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7665 |

| 1809.656616 | H5N4F1 | 0.0265 | * | 0.6432 |

| 1866.65564 | H5N5 | 0.0198 | * | 0.6229 |

| 1936.703247 | H5N4L1 | 0.0011 | ** | 0.7065 |

| 2012.728149 | H5N5F1 | 0.0143 | * | 0.6526 |

| 2023.78418 | H4N5E1 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7557 |

| 2158.761475 | H5N5F2 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7429 |

| 2209.783447 | H5N4L2 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7344 |

| 2231.77832 | H6N6 | 0.0012 | ** | 0.7122 |

| 2269.907959 | H5N5E1Ac2 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7916 |

| 2372.88916 | H4N6F1E1 | 0.0155 | * | 0.656 |

| 2547.91748 | H5N4F2L1E1 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7958 |

| 2550.886719 | H6N6E1 | 0.0232 | * | 0.6356 |

| 2604.955811 | H5N5F1L1E1 | 0.0014 | ** | 0.6725 |

| 2650.977295 | H5N5F1E2 | 0.0038 | ** | 0.681 |

| 2720.946777 | H6N5F1L2 | 0.0108 | * | 0.6583 |

| 2767.007324 | H6N5F1L1E1 | 0.0007 | *** | 0.7382 |

| 2813.028564 | H6N5F1E2 | 0.0002 | *** | 0.7164 |

| 3040.088135 | H6N5F1L2E1 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7613 |

| 3086.109375 | H6N5F1L1E2 | 0.0005 | *** | 0.7382 |

| 3132.130859 | H6N5F1E3 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.7925 |

| 3186.160889 | H6N5F2L2E1 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.802 |

| 3259.138916 | H7N6L2E1 | 0.0279 | * | 0.6139 |

| 3305.160156 | H7N6L1E2 | 0.0002 | *** | 0.7023 |

| 3405.21167 | H7N6F1L2E1 | < 0.0001 | *** | 0.8313 |

| 3532.219727 | H7N6L3E1 | 0.0018 | ** | 0.6857 |

Validating potential biomarkers in an independent test set

In this study, we find some potential biomarkers for distinguishing the early stage GC from healthy people, and the others for helping monitor the GC progression. Among them, core fucose and bisecting type N-glycan demonstrated greater potential for gastric cancer diagnosis as they yielded higher AUC value. Hence, we further validated their potential in an independent cohort. The validation set consisted 20 healthy controls and 40 GC patients. The demographic characteristics of the independent sample set was presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The clinical characteristics of participants in validation set

| Mean(min-max) or N0.% | Total: n=60 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-cancer: n=20 | GC: n=40 | ||

| Age, y | 44.95(31-75) | 61.30(29-84) | |

| Male | 11(55%) | 21(53%) | 32 |

| Female | 9 (45%) | 19 (47%) | 28 |

| CEA | 1.35 (0.49-2.90) | 26.43 (0.50-860.50) | |

| <5ng/mL | 20 | 36 | 56 |

| ≥5ng/mL | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| absent | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| CA19-9 | 16.72 (2.78-31.09) | 18.07(0.70-295.10) | |

| <37U/mL | 20 | 38 | 58 |

| ≥37U/mL | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| absent | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| CA125 | 4.19 (0.96-6.96) | 16.38(1.60-129.30) | |

| <35U/mL | 10 | 30 | 40 |

| ≥35U/mL | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| absent | 10 | 8 | 18 |

| AFP | 3.56 (0.51-7.79) | 3.48(0.80-15.40) | |

| <20ng/mL | 20 | 37 | 57 |

| ≥20ng/mL | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| absent | 0 | 3 | 3 |

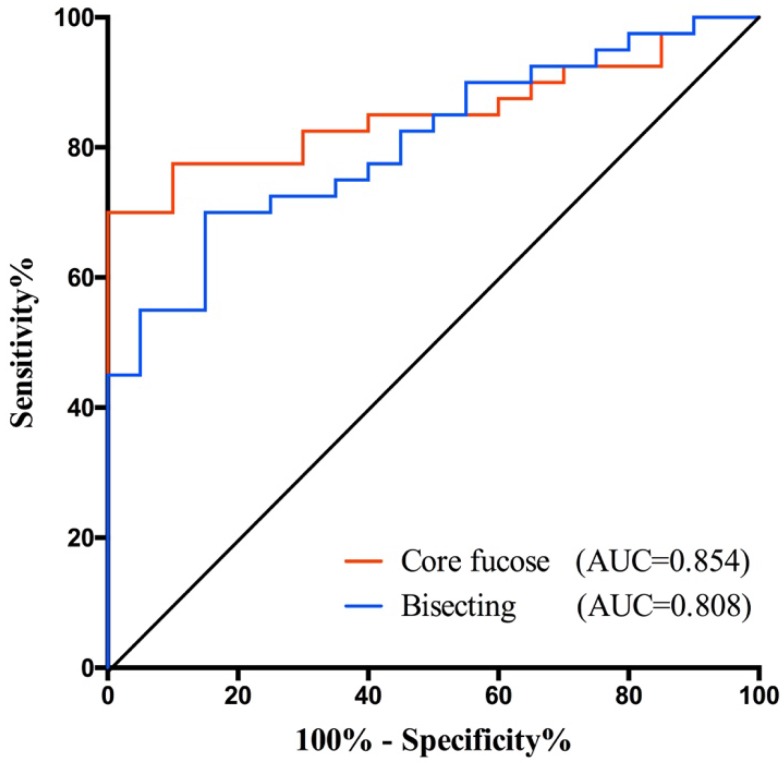

In validation set, both core fucose and bisecting type N-glycan were significantly decreased in gastric cancer (Supplementary Fig.S2), so that they still have a good performance in GC early detection. Their AUC values were 0.854 (95%CI: 0.7592 to 0.9483) and 0.808 (95%CI: 0.6999 to 0.9151), respectively (Fig. 4). And the specificity and sensitivity of these glyco-subclasses are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Fig 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses for the validation of potential GC early diagnose biomarker. The ROC was employed to evaluate the classification efficiency of the potential biomarkers including core fucose and bisecting type N-glycan that were decreased in GC. And their AUC values were 0.854 and 0.808, respectively.

Discussion

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most malignant cancers all around the world. Due to the imaging and serological examination defects, it is urgent to develop appropriate non-invasive biomarkers for gastric cancer diagnosis and monitoring. Glycosylation is a kind of posttranslational modification in the vast majority of proteins, responsible for modulating and controlling many of the biological roles of glycoproteins. Abnormal glycosylation is associated with disease progression, especially in cancer 24.

To date, there were several glycomic analyses in gastric cancer serum. However, the number of detected glycans was not complete enough in previous studies 4, 13, 18, 19, 20, 21. Some of reasons are that the inherent complexity of glycans and the wide dynamic range of clinically relevant samples like serum make comprehensive analyses of the glycome a challenging task, largely relying on the development of specialized analytical methods 25. MS is emerging as an enabling technology in the field of glycomics. Meanwhile, ongoing efforts into sample preparation strategies compatible with MS were taken to improve analytical results, such as different enrichment and derivatization methods 17, 26, 27. In this work, ethyl esterification derivatization of glycans was employed to increase their stability for MS analysis. With this method, we detected both neutral N-glycans and ethyl esterified sialic acid using MALDI-TOF MS, which allowed us to obtain more comprehensive serum glycomic analysis. We identified several glyco-subclasses classified based on their characteristic structures and the data showed the N-glycomic profiles of non-cancer participants and GC patients could be obviously distinguished. To our knowledge, we report for the first time that hybrid N-glycans is increased in GC patients, while the total bisecting type N-glycans and monoantennary N-glycans were decreased. Furthermore, we showed several individual N-glycans that either increase or decrease during occurrence and progression of gastric cancer.

In this study, we found the core fucose had the best performance with AUC value of 0.923, suggesting this glycol-subclass is most likely to be a novel biomarker for GC early diagnosis. Using DNA sequencer-assisted/fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis (DSA-FACE) analytical methodology, Long Liu et al. found a significant reduction of core focuse in serum, tissue and cell of gastric cancer 13. Fucosylation is catalyzed by fucosyltransferases, Fut8 is the only fucosyltransferase involved in core-fucosylation and Fut8 protein wad decreased in gastric cancer tissue. The up-regulation of Fut8 and its substrate (GDP-Tr) in human gastric cancer cells could lead to low proliferation 19. These results help to explain the possible mechanism of decreased core fucose in gastric cancer. However, there were only 9 glycan structures detected in these previous studies. In this work, there are more than 80 glycans identified, thus demonstrating serum core-fucoslated glycans decreased significantly in GC comparing to healthy controls in a more comprehensive way. The diagnosis performance also largely increased with AUC 0.923 which may due to comprehensively consideration of total core fucosylated glycans in serum. This potential biomarker also proved its excellent performance in GC early detection of an independent test set. However, this differs from what has been reported in other cancers, such as the increased core fucosylation of alpha-fetoprotein that was observed in HCC 12, 28. This suggested that fucosylated-glycan alteration might be cancer-specific and the molecular mechanism of the alteration in gastric cancer remains a critical challenge for future studies. This cancer-specific made core fucosylated glycans more promising as a potential biomarker for early diagnosis of GC.

GC stage-specific N-glycosylation was detected by high H5N5E1AC2 (m/z 2269.91) in advanced relative to early stage GC. Interestingly, a novel link between the GC metastasis status and the N-glycosylation was indicated from the N-glycome profiles. Peritoneal metastasis-specific N-glycan signatures included low H6N5F2L2E1 (m/z 3186.16) and H7N6F1L2E1 (m/z 3405.21) (both P < 0.0001) relative to advanced gastric cancer. This is the first study to identify specific N-glycan features of PMGC, providing potential glycan biomarkers to distinguish the AGC and the PMGC. If PMGC can be accurately predicted with these potential biomarkers before the operation, PMGC patients will avoid the mental and physical trauma from unnecessary surgery.

In conclusion, using comprehensive N-glycomic profiles analysis, we have identified several glyco-subclasses either up-regulated or down-regulated in gastric cancer compared to non-cancer group. Furthermore, we find several specific N-glycan structures to surveillance the progress of gastric cancer, especially the peritoneal metastasis. And then we validate the decreased core fucose could be great potential biomarker for early GC diagnose. Further studies are still needed to validate the potential of these findings as promising biomarkers and identify the role of protein glycosylation in gastric cancer pathology.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFA0501303), National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (2012CB8221004, 2013CB910503), National Natural Science Fund of China (81572352, 31470794, 31300671).

Abbreviations

- GC

gastric cancer; EGC: early stage gastric cancer

- AGC

advanced gastric cancer

- PMGC

peritoneal metastasis gastric cancer

- MALDI-TOF MS

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/ Ionization Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry

- MQ

Milli-Q water

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- NP-40

Nonidet P-40

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-carbodiimide

- PNGase F

peptide-N-glycosidase F

- 2,5-DHB

2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid

- ACN

acetonitrile (ACN)

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- CEA

carcinoembryonic antigen

- CA19-9

carbohydrate antigen 19-9

- CA125

carbohydrate antigen 125

- AFP

alpha fetoprotein

- ROC

receiver operating characteristics

- CI

confidence interval

- AUC

Area under the Curve

- H

hexose

- N

N-acetylhexosamine; F: fucose

- L

α-2,3 sialic acid; E: α-2,6 sialic acid.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D. et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607–15. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leja M, You W, Camargo MC, Saito H. Implementation of gastric cancer screening - the global experience. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:1093–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bones J, Byrne JC, O'Donoghue N, McManus C, Scaife C, Boissin H. et al. Glycomic and glycoproteomic analysis of serum from patients with stomach cancer reveals potential markers arising from host defense response mechanisms. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1246–65. doi: 10.1021/pr101036b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi J, Kim SG, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography and conventional endoscopy for prediction of depth of tumor invasion in early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2010;42:705–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kikuchi H, Kamiya K, Hiramatsu Y, Miyazaki S, Yamamoto M, Ohta M. et al. Laparoscopic narrow-band imaging for the diagnosis of peritoneal metastasis in gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3954–62. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3781-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalnina Z, Meistere I, Kikuste I, Tolmanis I, Zayakin P, Line A. Emerging blood-based biomarkers for detection of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11636–53. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinho SS, Carvalho S, Marcos-Pinto R, Magalhaes A, Oliveira C, Gu J. et al. Gastric cancer: adding glycosylation to the equation. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:664–76. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park HM, Hwang MP, Kim YW, Kim KJ, Jin JM, Kim YH. et al. Mass spectrometry-based N-linked glycomic profiling as a means for tracking pancreatic cancer metastasis. Carbohydr Res. 2015;413:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alley WR Jr, Vasseur JA, Goetz JA, Svoboda M, Mann BF, Matei DE. et al. N-linked glycan structures and their expressions change in the blood sera of ovarian cancer patients. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:2282–300. doi: 10.1021/pr201070k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyselova Z, Mechref Y, Al Bataineh MM, Dobrolecki LE, Hickey RJ, Vinson J. et al. Alterations in the serum glycome due to metastatic prostate cancer. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1822–32. doi: 10.1021/pr060664t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamiyama T, Yokoo H, Furukawa J, Kurogochi M, Togashi T, Miura N. et al. Identification of novel serum biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma using glycomic analysis. Hepatology. 2013;57:2314–25. doi: 10.1002/hep.26262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L, Yan B, Huang J, Gu Q, Wang L, Fang M. et al. The identification and characterization of novel N-glycan-based biomarkers in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Qiu H, Lee RK, Chen W, Li J. Methylamidation for sialoglycomics by MALDI-MS: a facile derivatization strategy for both alpha2,3- and alpha2,6-linked sialic acids. Anal Chem. 2010;82:8300–6. doi: 10.1021/ac101831t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang P, Mechref Y, Novotny MV. High-throughput solid-phase permethylation of glycans prior to mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:721–34. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey DJ. Derivatization of carbohydrates for analysis by chromatography; electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879:1196–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiding KR, Blank D, Kuijper DM, Deelder AM, Wuhrer M. High-throughput profiling of protein N-glycosylation by MALDI-TOF-MS employing linkage-specific sialic acid esterification. Anal Chem. 2014;86:5784–93. doi: 10.1021/ac500335t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozcan S, Barkauskas DA, Renee Ruhaak L, Torres J, Cooke CL, An HJ. et al. Serum glycan signatures of gastric cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:226–35. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao YP, Xu XY, Fang M, Wang H, You Q, Yi CH. et al. Decreased core-fucosylation contributes to malignancy in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bones J, Mittermayr S, O'Donoghue N, Guttman A, Rudd PM. Ultra performance liquid chromatographic profiling of serum N-glycans for fast and efficient identification of cancer associated alterations in glycosylation. Anal Chem. 2010;82:10208–15. doi: 10.1021/ac102860w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruhaak LR, Barkauskas DA, Torres J, Cooke CL, Wu LD, Stroble C. et al. The Serum Immunoglobulin G Glycosylation Signature of Gastric Cancer. EuPA Open Proteom. 2015;6:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.euprot.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldman R, Ressom HW, Varghese RS, Goldman L, Bascug G, Loffredo CA. et al. Detection of hepatocellular carcinoma using glycomic analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1808–13. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang SJ, Zhang H. Glycan analysis by reversible reaction to hydrazide beads and mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2012;84:2232–8. doi: 10.1021/ac202769k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mechref Y, Hu Y, Garcia A, Zhou S, Desantos-Garcia JL, Hussein A. Defining putative glycan cancer biomarkers by MS. Bioanalysis. 2012;4:2457–69. doi: 10.4155/bio.12.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Zhang N, Wan D, Cui M, Liu Z, Liu S. Mass spectrometry-based analysis of glycoproteins and its clinical applications in cancer biomarker discovery. Clin Proteomics. 2014;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Peng Y, Bin Z, Wang H, Lu H. Highly specific purification of N-glycans using phosphate-based derivatization as an affinity tag in combination with Ti(4+)-SPE enrichment for mass spectrometric analysis. Analytica chimica acta. 2016;934:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang S, Li Y, Shah P, Zhang H. Glycomic analysis using glycoprotein immobilization for glycan extraction. Anal Chem. 2013;85:5555–61. doi: 10.1021/ac400761e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyoshi E, Moriwaki K, Nakagawa T. Biological function of fucosylation in cancer biology. J Biochem. 2008;143:725–9. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.