Abstract

Tobacco smoking prevalence remains low in many African countries. However, growing economies and the increased presence of multinational tobacco companies in the African Region have the potential to contribute to increasing tobacco use rates in the future. This paper used data from the 2014 Global Progress Report on implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), as well as the 2015 WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, to describe the status of tobacco control and prevention efforts in countries in the WHO African Region relative to the provisions of the WHO FCTC and MPOWER package. Among the 23 countries in the African Region analyzed, there are large variations in the overall WHO FCTC implementation rates, ranging from 9% in Sierra Leone to 78% in Kenya. The analysis of MPOWER implementation status indicates that opportunities exist for the African countries to enhance compliance with WHO recommended best practices for monitoring tobacco use, protecting people from tobacco smoke, offering help to quit tobacco use, warning about the dangers of tobacco, enforcing bans on tobacco advertising and promotion, and raising taxes on tobacco products. If tobacco control interventions are successfully implemented, African nations could avert a tobacco-related epidemic, including premature death, disability, and the associated economic, development, and societal costs.

Keywords: WHO Framework Convention on, Tobacco Control, WHO FCTC Articles, MPOWER, Tobacco control and prevention policy status in Africa, WHO FCTC and MPOWER implementation status, WHO African Region

1. Introduction

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable deaths in the world (World Health Organization, 2008). During the 20th century, the tobacco epidemic contributed to an estimated 100 million deaths worldwide (World Health Organization, 2008). Tobacco use continues to kill nearly 6 million persons each year, including approximately 600,000 from secondhand smoke (World Health Organization, 2008; Eriksen et al., 2012). If the current trend persists, it is projected that tobacco use will kill over 8 million people per year by 2030, with 80% of these deaths occurring in low or middle-income countries (World Health Organization, 2008; Eriksen et al., 2012). Cigarette smoking has declined significantly in developed countries; however, it is increasing in low and middle income countries (Drope, 2011). Many countries in the African Region have relatively low cigarette smoking prevalence as compared with other World Health Organization (WHO) Regions (Eriksen et al., 2012). However, economic growth outlook in the Region, combined with increased presence of multinational tobacco companies and product marketing, has the potential to increase tobacco use and tobacco-related disease and death (Doku, 2010).

In response to the global tobacco epidemic, most countries have pledged to comply with the provisions of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). The WHO FCTC, which came into force in 2005, is the first global evidence-based public health treaty to protect people from the negative consequences of tobacco use (World Health Organization, 2003; World Health Organization, 2015a). In the decade since WHO FCTC was introduced, steady progress on implementing WHO FCTC provisions has been achieved in many countries, including increasing tobacco taxes, expanding protections from tobacco smoke through smoke-free policies, regulating additives in tobacco products, prohibiting tobacco displays at points of sale, introducing large health warnings on packages, and using mobile and internet technologies for promoting smoking cessation (World Health Organization, 2014).

Subsequently, in 2008, WHO introduced the MPOWER measures, which assist in the country-level implementation of effective interventions to reduce the demand for tobacco that are contained in the WHO FCTC (World Health Organization, 2015b). The policy package consists of the following measures: M: monitor tobacco use; P: protect people from tobacco smoke; O: offer help to quit tobacco use; W: warn about the dangers of tobacco; E: enforce bans on tobacco advertising and promotion; R: raise taxes on tobacco products. The MPOWER package of tobacco control policies and interventions has been used effectively by countries to plan, build, and evaluate progress toward implementing the WHO FCTC’s provisions (World Health Organization, 2015b).

We used data from the 2014 Global Progress Report on implementation of the WHO FCTC, as well as the 2015 WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, to describe the status of tobacco control and prevention efforts in countries in the WHO African Region relative to the provisions of 16 substantive Articles of the WHO FCTC and the MPOWER package. A comparison of the WHO FCTC implementation status between the African Region and the remaining five WHO Regions is also presented.1 Given some of the challenges that the African Region faces in the fight against tobacco use, this paper highlights the importance of proactive interventions, in compliance with WHO FCTC and MPOWER provisions, to prevent and control tobacco use.

2. Method

2.1. WHO FCTC implementation status

As of June, 2015, 38 of the 47 countries in the WHO African Region had ratified the WHO FCTC, and 5 countries are in accession status. Mozambique has signed but not ratified the Treaty, and Eritrea, Malawi, and South Sudan have neither signed nor ratified it (United Nations, 2015). Parties that have ratified the WHO FCTC have reporting obligations, and are required to submit standardized progress reports to the Convention Secretariat in each reporting cycle by filling out a standardized questionnaire. The Convention Secretariat maintains the global progress reports and the implementation database to track the achievements, as well as the areas in which more progress is warranted (World Health Organization, 2015a, 2014). In the 2014 reporting cycle, 73% of Parties (i.e. 130 in 177 countries) submitted their implementation reports to the Convention Secretariat. In the WHO African Region, 23 of the 43 Parties (i.e. countries in ratification or accession status) submitted the report.

The reporting instrument contains information on ~230 indicators relevant to a list of WHO FCTC Articles, from which a select 148 indicators are used to assess the current status of implementation of select WHO FCTC Articles (World Health Organization, 2014). The 2014 Global Progress Report provides information, for each country, on the number of indicators considered under a particular Article, as well as the maximum number (or score) which a Party (country) can be given for complying with the requirements of that Article. Compliance or implementation of a particular indicator mainly refers to whether the reporting countries recorded affirmative or negative response for that indicator (World Health Organization, 2014). For this study, the implementation rate for each WHO FCTC Article in each country was calculated as the ratio of implemented indicators to the total number of indicators considered under that Article. The average implementation rate for each Article refers to the average (i.e. mean) of the implementation rates for countries in the Region.

Table 1 provides further details on each Article assessed in this study. Out of the total 38 Articles in the WHO FCTC, 16 Articles are identified as substantive Articles in the 2014 Global Progress Report: Article 5 lays out the general obligations for the party to develop, implement, periodically update and review comprehensive multisectoral national tobacco control strategies, plans and programs; Articles 6, 8–14 contain the core demand reduction provisions; Articles 15–17 contain the core supply reduction measures; Article 18 contains the provisions pertaining to the protection of the environment; Article 19 lays out the liability provisions; Article 20 calls on parties to develop and promote research, surveillance and exchange of information; and Article 22 lays out the obligations about cooperation in the scientific, technical, and legal fields, and the provision of related expertise (World Health Organization, 2003).

Table 1.

Brief description of the selected WHO FCTC Articles.

| Article 5 | General obligations — requires Parties to establish essential infrastructure for tobacco control, including a national coordinating mechanism, and to develop and implement comprehensive, multisectoral tobacco-control strategies, plans and legislation to prevent and reduce tobacco use, nicotine addiction and exposure to tobacco smoke. |

| Article 6 | Price and tax measures — to reduce the demand for tobacco, including prohibiting or restricting sales to and/or importations by international travelers, of tax- and duty-free tobacco products. |

| Article 8. | Protection from exposure to tobacco smoke — in indoor workplaces, public transport, indoor public places and other public places. |

| Article 9. | Regulation of the contents of tobacco products — by testing and measuring the contents and emissions of tobacco products. |

| Article 10. | Regulation of tobacco product disclosures — requiring manufacturers and importers of tobacco products to disclose information about the contents, toxic constituents, and emissions. |

| Article 11. | Packaging and labeling of tobacco products — requires each Party to adopt and implement effective measures to prohibit misleading tobacco packaging and labeling; ensure that tobacco product packages carry large health warnings and messages describing the harmful effects of tobacco use. |

| Article 12. | Education, communication, training and public awareness — through all available communication tools, such as media campaigns, educational programs and training; training and sensitization programs among a broad range of target groups, including media professionals and decision-makers. |

| Article 13. | Comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship and restricting the use of direct or indirect incentives that encourage the purchase of tobacco products by the public. |

| Article 14. | Demand reduction measures concerning tobacco dependence and cessation — by promoting the cessation of tobacco use, diagnosis and treatment of tobacco dependence, and counseling services on cessation of tobacco use. |

| Article 15. | Measures to control illicit trade in tobacco products — by marking of tobacco packaging to enable tracking and tracing, the monitoring of cross-border trade, legislation to be enacted, and confiscation of proceeds derived from the illicit trade in tobacco products. |

| Article 16. | Prohibition of sales to and by minors including prohibiting the sale of tobacco products in any manner by which they are directly accessible; prohibiting the manufacture and sale of sweets, snacks, toys or any other objects in the form of tobacco products which appeal to minors; and ensuring that tobacco vending machines are not accessible to minors and do not promote the sale of tobacco products to minors. |

| Article 17. | Provision of support for economically viable alternative activities for tobacco workers, growers and, as the case may be, individual sellers. |

| Article 18. | Protection of the environment and the health of persons in relation to the environment in respect of tobacco cultivation and manufacture within their respective territories. |

| Article 19. | Liability provisions to deal with criminal and civil liability, including compensation where appropriate. |

| Article 20. | Research, surveillance and exchange of information with research that addresses the determinants and consequences of tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke as well as research for identification of alternative crops; training and support for all those engaged in tobacco control activities, including research, implementation and evaluation. |

| Article 22. | International cooperation and assistance to promote the transfer of technical, scientific and legal expertise and technology to establish and strengthen national tobacco control strategies. |

Source: World Health Organization (2003). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, Switzerland; available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241591013.pdf; and The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: an overview. WHO FCTC. The World Health Organization. January 2015; available at: http://www.who.int/WHOFCTC/WHO_FCTC_summary_January2015.pdf

2.2. MPOWER implementation status

We used data from the 2015 WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic to summarize the MPOWER implementation status in 47 countries in the WHO African Region (World Health Organization, 2015c). The implementation status of MPOWER tracks country progress on select indicators, unlike the WHO FCTC global progress report where a comprehensive list of 148 indicators pertaining to 16 selected Articles are considered. The MPOWER report measures the extent of enforcement on specific indicators corresponding to each of the MPOWER components.

The status of the ‘M’ component is measured by the extent to which countries have survey data on tobacco use among adults and youths that are recent and representative. The status of the ‘P’ component is measured by assessing country specific legislation to determine the extent to which smoke-free laws are implemented that prohibit smoking in indoor environment at all times in eight different types of location (World Health Organization, 2015c). The ‘O’ component is tracked by assessing achievement in treatment for tobacco dependence, which is based on whether the country has available nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), non-NRT tobacco dependence treatment, reimbursement for either, and a national toll-free quit line (World Health Organization, 2015c). Implementation status of the ‘W’ is assessed by two main sub-components: attributes of warning labels on tobacco packaging, and the frequency and characteristics of the anti-tobacco mass media campaigns by the respective countries (World Health Organization, 2015c). The ‘E’ component describes the country level achievements in banning tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, and was assessed by whether the bans covered various forms of direct advertising, including television, radio, print media, billboards and outdoor advertising, and point of sale; additionally, various forms of indirect advertising were assessed, including promotions, discounts, coupons, free distribution of tobacco products, brand stretching, sharing, and placement activities, and sponsorship including corporate social responsibility programs (World Health Organization, 2015c). To gauge the status of the ‘R’ component, countries are classified according to the percentage contribution of all taxes to the retail price of tobacco products (World Health Organization, 2015c).

3. Results

3.1. Implementation status of WHO FCTC provisions in the African Region

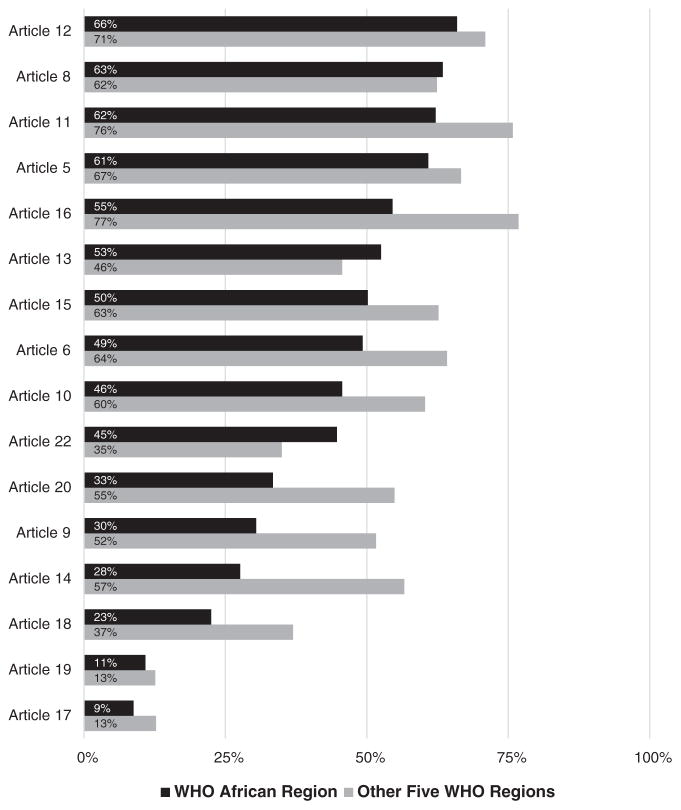

Fig. 1 shows the average implementation rates of selected WHO FCTC Articles, comparing the African Region with the remaining five WHO Regions. The articles reporting the highest implementation rates across the 23 African countries included in the analysis are: Article 12 (66%; Education, communication, training and public awareness), Article 8 (63%; Protection from exposure to tobacco smoke), Article 11 (62%; Packaging and labeling of tobacco products), and Article 5 (61%; General obligations). The articles for which the implementation rates were moderate were: Article 16 (55%; Sales to and by minors), Article 13 (53%; Tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship), Article 15 (50%; Illicit trade in tobacco products), Article 6 (49%; Price and tax measures to reduce the demand for tobacco), Article 10 (46%; Regulation of tobacco product disclosures), Article 22 (45%; Cooperation in the scientific, technical and legal fields and provision of related expertise), and Article 20 (33%; Research, surveillance and exchange of information). The articles reporting the lowest implementation rates were: Article 9 (30%; Regulation of the contents of tobacco products), Article 14 (28%; Demand reduction measures concerning tobacco dependence and cessation), Article 18 (23%; Protection of the environment and the health of persons), Article 19 (11%; Liability), and Article 17 (9%; Provision of support for economically viable alternative activities).

Fig. 1.

Average implementation rate of substantive articles of the Convention by the Parties reporting in 2014. Notes: The implementation rates for the African Region are based on data from 23 African countries [see annex 3, pp. 79–85 in World Health Organization, 2014]: Algeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Togo, Uganda, and United Republic of Tanzania. The average implementation rate for each Article refers to the average (i.e. mean) of the implementation rates for countries in the Region. The calculation of the implementation rate for Article 17 excludes data from Madagascar, Mauritania, Senegal, and Seychelles; and for Article 18 excludes data from Gambia, Seychelles, and Togo. The implementation rates for ‘other five Regions’ are based on data from 107 countries (Parties) [see annex 3, pp. 79–85 in World Health Organization, 2014] in WHO Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, Southeast Asia, the Americas, and Western Pacific Regions. The implementation rates for Articles 17 and 18 are based on data from 81 and 69 countries in those five Regions, respectively.

Fig. 1 also shows the average implementation rates by 107 countries in the remaining five WHO Regions. The overall implementation rate, calculated based on the implementation rates by article as shown in Fig. 1, was 43% for the African Region, as compared to 53% by the countries in the remaining WHO Regions. By Article, significant differences in implementation rates for the African Region vs. other Regions were observed for: Article 14 (28% vs. 57%, p = 0.000); Article 16 (55% vs. 77%, p = 0.000); Article 20 (33% vs. 55%, p = 0.002); Article 9 (30% vs. 52%; p = 0.019); Article 6 (49% vs. 64%; p = 0.066); and Article 11 (62% vs. 76%; p = 0.055).2

Table 2 shows the status of implementation of select Articles by the Parties in the WHO African Region. Among the 23 countries in the African Region analyzed, there are large variations in the overall implementation rates, ranging from 9% in Sierra Leone to 78% in Kenya. The countries with relatively high overall implementation rates (i.e. above 60%) were: Kenya, Seychelles, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Senegal, and Ghana. Countries with moderate implementation rates (i.e. between 30% and 60%) were: Mauritius, Togo, Uganda, Gabon, Madagascar, Gambia, Algeria, Mali, Benin, South Africa, and Congo. Countries with relatively low implementation rates (i.e. less than 30%) included: Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Sao Tome and Principe, United Republic of Tanzania, Mauritania, and Sierra Leone.

Table 2.

Status of implementation of substantive Articles (Art.) by the Parties in the WHO African Region.

| Number of indicators under corresponding article |

Art. 5 |

Art. 6 |

Art. 8 |

Art. 9 |

Art. 10 |

Art. 11 |

Art. 12 |

Art. 13 |

Art. 14 |

Art. 15 |

Art. 16 |

Art. 17 |

Art. 18 |

Art. 19 |

Art. 20 |

Art. 22 |

Average implementation rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 6 | 3 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 20 | 13 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 19 | 7 | ||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Number of indicators implemented in each country | |||||||||||||||||

| Kenya | 6 | 3 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 5 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 78% |

| Seychelles | 4 | 3 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 13 | 10 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 4 | 4 | 67% |

| Burkina Faso | 6 | 2 | 17 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 7 | 66% |

| Nigeria | 4 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 62% |

| Senegal | 3 | 1 | 15 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 8 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 61% |

| Ghana | 5 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 13 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 14 | 3 | 61% |

| Mauritius | 5 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 6 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 56% |

| Togo | 4 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 1 | N/A | 0 | 13 | 3 | 53% |

| Uganda | 3 | 1 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 5 | 52% |

| Gabon | 4 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 46% |

| Madagascar | 5 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 8 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 45% |

| Gambia | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 4 | 0 | N/A | 0 | 9 | 5 | 45% |

| Algeria | 3 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 42% |

| Mali | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 42% |

| Benin | 2 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 40% |

| South Africa | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 39% |

| Congo | 3 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 35% |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 3 | 1 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 29% |

| Cameroon | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 24% |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 3 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 21% |

| United Rep. of Tanzania | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 15% |

| Mauritania | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10% |

| Sierra Leone | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9% |

Notes: The table is a subset of the table in Annex 3 pp. 79–85 in World Health Organization, 2014, including the countries in the WHO African Region only. Data for 23 out of 47 countries in WHO African Region are reported. The values are the maximum number (or score) which a Party can be given for complying with the requirements of corresponding articles. The average implementation rate for each country refers to the average (i.e. mean) of the implementation rates by Article. The calculation of the average implementation rates for Seychelles, Senegal, Madagascar, and Mauritania excluded Article 17. The average implementation rates for Seychelles, Togo, and Gambia excluded Article 18.

3.2. Implementation status of MPOWER in the African Region

(M) Monitor tobacco use

Article 20 of the WHO FCTC calls for countries to conduct tobacco-related surveillance to monitor the impact of tobacco use and tobacco prevention programs and policies on their populations. According to the 2015 WHO Report, of the 47 countries in the WHO African Region, the seven countries that have recent and representative tobacco prevalence data for both adults and youth were: Algeria, Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Sao Tome and Principe, South Africa, and Uganda. Twenty-two countries had recent and representative prevalence data for either adults or youth, and 18 countries did not have any recent data (i.e. data from 2009 or later) that are representative of the national population. On the other hand, two-thirds of the countries (99/146) in the remaining WHO regions have recent and representative tobacco prevalence data for both adults and youth.

(P) Protect people from second-hand smoke exposure

WHO FCTC Article 8 calls for countries to enact and enforce laws requiring completely smoke-free environments in all indoor public spaces and workplaces. Such laws protect nonsmokers from the danger of secondhand smoke exposure, and their enforcement is proven to reduce cigarette smoking prevalence and improve health outcomes. According to the 2015 WHO Report, 6 of the 47 countries (13%) in the African Region (i.e. Burkina Faso, Chad, Congo, Madagascar, Namibia, and Seychelles) have either enacted policies requiring completely smoke-free public places, or had subnational laws protecting at least 90% of the population. In the remaining WHO Regions, 30% of countries (43/141) have enacted similar policies.3 However, compliance with these smoke-free policies varies widely by country, and only Seychelles is reported to have achieved a high degree of compliance. In the 2010 African Tobacco Situational Analysis, six African countries noted that enforcement of their smoke-free polices were a challenge, and that the law was regularly violated (Drope, 2011).

(O) Offer help to quit tobacco use

WHO FCTC Article 14 calls for countries to promote tobacco cessation and treatment for tobacco dependence through appropriate programs and services. However, very few low or middle income countries provide adequate access to cessation services. According to the WHO 2015 Report, 20 countries that offer cessation counseling or nicotine replacement therapy cover the costs for at least one of these services,4 16 countries that offer cessation counseling or nicotine replacement therapy do not cover any portion of the cost for these services; and 10 out of 47 countries in the WHO African Region do not offer any cessation programs. On the other hand, out of 148 countries in the remaining 5 WHO Regions, 24 countries (16%) offer national quit line, and both NRT and some cessation services cost-covered, 86 countries (58%) offer NRT and/or some cessation services (at least one of them cost-covered), 32 countries (22%) have NRT and/or cessation services (neither cost-covered), and 6 countries (4%) do not offer any cessation program.

(W) Warn about the dangers of tobacco

Article 11 of the WHO FCTC requires governments to implement policies that warn the public about health dangers of tobacco use. The use of large pictorial warning labels on tobacco packaging is effective for raising public awareness about the health impact of tobacco use. Approximately 20% of middle-income countries and 8% of low income countries have policies that require appropriately sized graphic warning labels on tobacco packages; in the African Region, these countries include: Madagascar, Mauritius, Namibia, Niger, and Seychelles (World Health Organization, 2015c, 2013). During 2014–2015, several other African countries included requirements for pictorial warnings in their national legislations, including: Senegal, Kenya, Namibia, Chad and Burkina Faso (WHO FCTC News, 2015). Half of the countries in the African Region (23 out of 47) had either small warnings or no warnings on the cigarette packages, as compared to the one-fourth (37/148) of the countries in the other 5 WHO Regions. WHO FCTC Article 12 calls on countries to increase public awareness about the dangers of tobacco by using targeted and appropriate communication strategies. Mass media anti-tobacco campaigns that give hard-hitting depictions of the harm caused by tobacco are effective in raising awareness, reducing tobacco use, and increasing quit attempts (World Health Organization, 2013). Some African countries have conducted national anti-tobacco mass media campaigns (e.g. Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Mauritius, Senegal, Togo, and Uganda), but most of the countries (at least 31 out of 47) did not launch national campaign with duration of at least three weeks5 between July 2012 and June 2014. Accordingly, additional efforts are critical to increasing public awareness about the health impact of tobacco use.

(E) Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

The tobacco industry uses direct and indirect tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) strategies that are effective in increasing tobacco consumption (National Cancer Institute, 2008) and the likelihood that adolescents will start smoking (Lovato et al., 2011). The industry has aggressively marketed tobacco in African countries (Drope, 2011; Doku, 2010). The WHO FCTC Article 13 requires governments to adopt and enforce comprehensive bans on all TAPS. Countries that implemented comprehensive TAPS bans, which include prohibition of direct media advertising, as well as indirect marketing such as product placement or sponsorship of community events, have demonstrated their effectiveness in reducing tobacco consumption (World Health Organization, 2013). Partial bans have not been found effective in reducing tobacco consumption (World Health Organization, 2013). In the African Region, nine countries, including Chad, Eritrea, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Niger and Togo, have enacted comprehensive anti-TAPS laws. Laws that partially ban TAPS have been adopted in 18 African countries, and 20 countries have weak anti-TAPS policies or no bans. In the remaining WHO Regions, 39 in 148 countries have weak anti-TAPS policies or no bans.

(R) Raise taxes on tobacco products

WHO FCTC Article 6 promotes the adoption of tax and price policies on tobacco products. Tobacco taxation that results in increased product prices is extremely effective in reducing consumption and initiation of tobacco use. Taxation is also an efficient way for governments to generate revenue that may be used to implement tobacco control initiatives (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2011; Chaloupka et al., 2012). WHO recommends that cigarette taxes should constitute 75% or more of the retail price (World Health Organization, 2015c). In the African Region, Madagascar and Seychelles meet this WHO FCTC provision, where the shares of total taxes in the retail price of the most widely sold brand of cigarettes are 80% in both countries. In general, considerable variations exist in the levels and structure of tobacco taxes across the African countries. As of 2014, countries with higher cigarette taxes (i.e. 50% or more) include: Algeria (51%), Botswana (63%), Comoros (51%), Eritrea (55%), Madagascar (80%), Mauritius (73%), Seychelles (80%), Swaziland (53%), and Zimbabwe (60%). The countries where the shares of total taxes in the retail price of the most widely sold brand of cigarettes are 25% or less include: Angola (24%), Benin (9%), Cabo Verde (22%), Cameroon (21%), Ethiopia (19%), Guinea-Bissau (19%), Liberia (19%), Malawi (21%), Mali (19%), Mauritania (25%), Nigeria (21%), Rwanda (23%), Sao Tome and Principe (25%), Sierra Leone (20%), Togo (13%), and Zambia (21%). The mean values of the shares of total taxes in the retail price of the most widely sold brand of cigarettes were 37% and 55% for the WHO African Region and the rest of the 5 WHO Regions, respectively. While the majority of the countries in the WHO African Region (31/47) have uniform excise tax system in place, nine countries have reported to have been applying multi-tiered system with varying tax rates.

4. Discussion

The findings from this study reveal that the majority of African countries have ratified the WHO FCTC, and in general, have not fully met their obligations under the WHO FCTC provisions. The analysis of MPOWER implementation status also indicates that opportunities exist for countries in the African Region to enhance compliance with these WHO recommended best practices. However, it is important to note that the compliance and implementation status of WHO FCTC and MPOWER reported in this study involved different methodological approaches; therefore, the progress status corresponding to a particular Article under WHO FCTC and corresponding MPOWER component may not always correlate. For instance, Article 6 includes three indicators in the WHO FCTC progress report (i.e. tax measures, prohibiting or restricting sales of tax- and duty-free tobacco products to international travelers, and prohibiting or restricting importations of tax- and duty-free tobacco products by international travelers), whereas the corresponding ‘R’ component only considers the existing tax rates as a percentage of the retail price. In that case, a country that implemented all three indicators but had a low tax rate would score 100% in the WHO FCTC progress report, but low in terms of status of the ‘R’ component in MPOWER. Similarly, Article 20 in the WHO FCTC report considers 19 indicators in the realm of research, surveillance, and exchange of information, whereas ‘M’ in MPOWER focuses only on the surveillance indicator. The implementation status of WHO FCTC is based on data from 23 of the 43 African countries in ratification or accession status. Also, the reported WHO FCTC implementation rates do not capture the extent of enforcement of the WHO FCTC provisions in each respective country. Notwithstanding these potential limitations, reporting the status under both frameworks provides important information on a country’s standings in the fight against the tobacco epidemic.

The relatively low prevalence of tobacco use in Africa has the potential to increase in the future as Regional economies develop. The tobacco industry in the African Region is increasingly active, introducing marketing strategies targeting potential future smokers, particularly vulnerable populations such as youth and women (Network of African Science Academies, 2014; Lee et al., 2012; Njoumemi et al., 2011). Despite relatively lower cigarette smoking prevalence among adults in the African Region, among boys, smoking prevalence in the African Region (9%) is higher or comparable to other developing Regions such as the Eastern Mediterranean (8%), Southeast Asia (8%), and Western Pacific (6%) Regions. The cigarette smoking prevalence among girls in the African Region (3%) is also slightly higher compared to the Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, and Western Pacific Regions (Eriksen et al., 2012; Blecher and Ross, 2013). This suggests that future smoking prevalence in Africa has the potential to increase to levels that are comparable to that of other Regions (Blecher and Ross, 2013).

The economic and demographic trends in Africa present several challenges in the fight against tobacco use. Africa registered economic growth rates at par with the rest of the world during the late 1990s, and higher than the global average after 2001 (Sala-i-Martin and Pinkovskiy, 2010). Economic development and improvements in health have led to increased life expectancy, with longer life spans providing more opportunity for tobacco-related illness to take hold. Additionally, relative to other Regions, Africa’s population has grown considerably, and is expected to continue to grow even more rapidly during the 21st century (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2011; Mendez et al., 2012). More specifically, it is projected that Africa’s population share in the world will grow from the current level of 12% to 30% by 2100 (Mendez et al., 2012). The economic and demographic trends, along with highly accessible and affordable tobacco products, offer high potential for tobacco consumption growth in the relatively untapped African market (Blecher and Ross, 2013). Moreover, lower compliance with the WHO FCTC and MPOWER measures may further heighten the prospect of an ensuing tobacco epidemic. In the absence of a comprehensive and evidence based tobacco prevention and control interventions, it is projected that cigarette smoking prevalence in the African Region will increase by nearly 39% by 2030, from 15.8% in 2010 to 21.9%; this would represent the largest increase in comparison to any other Regions globally (Blecher and Ross, 2013; Mendez et al., 2012). Another study on global trends and projections for tobacco use during 1990 to 2025 estimated high probabilities (≥95%) of increase in tobacco smoking prevalence among men for about a third of countries in the African Region (Bilano et al., 2015).

The Global Progress Report identified several barriers in the implementation of the WHO FCTC provisions, including the tobacco industry interference, lack of political support, inadequate inter-sectoral coordination, limited expertise, low priority given to tobacco control in non-health sectors and institutions, paucity of data, weak monitoring, and lack of research systems (World Health Organization, 2014, p. 8). Additionally, the tobacco industry often challenges the countries in domestic courts in light of the prevailing international trade and investment agreements, bearing implications for effective implementation of tobacco-control measures (World Health Organization, 2014, p. 9).

Along with implementing the regulatory and governing principles of the WHO FCTC and MPOWER frameworks, increasing public awareness of tobacco control legislation and vigilance in monitoring and enforcement are key factors for successful policy implementation (Drope, 2011). Further, in order to reduce the likelihood of a future tobacco epidemic, enhanced efforts are warranted to understand and counteract tobacco industry influences (Network of African Science Academies, 2014). If tobacco control interventions are successfully implemented, African nations could avert a tobacco-related epidemic, including premature death, disability, and the associated economic, development, and societal costs.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research is supported in part by the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use through the CDC Foundation with grants from Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Shanna Cox, MSPH; Deliana Kostova, PhD; Jennifer Tucker, MPA; Brian A. King, PhD; Indu B. Ahluwalia, PhD; Krishna M. Palipudi, PhD; Shaoman Yin, PhD — Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Footnotes

The six WHO Regions are used in the analysis: African Region, Region of the Americas, South-East Asia Region, European Region, Eastern Mediterranean Region, and Western Pacific Region. The sub-Saharan Africa and some of the North African countries are included in the WHO African Region, while most of the North African countries are included in the Eastern Mediterranean Region.

The reported p-values are from t-tests. Chi-square tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests produced similar results.

7 countries did not report data.

Data for South Sudan was not reported.

Data for 6 countries were not reported.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.

Transparency Document

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- Bilano V, Gilmour S, Moffi T, et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990–2025: An analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO Comprehensive Information Systems for Tobacco Control. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015];Lancet. 2015 2015(385):966–976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60264-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60264-1 http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)60264-1/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blecher E, Ross H. Tobacco use in Africa: tobacco control through prevention. [Last accesses on November 09, 2015];Am Cancer Soc. 2013 http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@internationalaffairs/documents/document/acspc-041294.pdf.

- Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT. Reviews: tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015];Tob Control. 2012 (21):172–180. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/21/2/172. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Doku D. The tobacco industry tactics – a challenge for tobacco control in low and middle income countries. [Accessed on November 09, 2015];Afr Health Sci. 2010 10(2):201–203. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2956281/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drope J. Tobacco Control in Africa: People, Politics and Policies. Anthem Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Accessed on November 09, 2015]. http://www.idl-bnc.idrc.ca/dspace/bitstream/10625/47373/1/IDL-47373.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen M, Mackay J, Ross H. The Tobacco Atlas. 4. American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia and World Lung Foundation; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Effectiveness of Tax and Price Policies for Tobacco Control. Vol. 14. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 2011. [Last accessed on No-vember 09, 2015]. IARC handbooks of cancer prevention, tobacco control. http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/prev/handbook14/handbook14-0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015];Cancer Causes Control. 2012 23(Suppl 1):117–129. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0 (Epub 2012 Feb 28) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22370696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015];Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 (10) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2. Art. No.: CD003439. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21975739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mendez D, Alshanqeety O, Warner KE. The potential impact of smoking control policies on future global smoking trends. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015];Tob Control. 2012 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050147 (tobaccocontrol-2011-050147. Published Online First: 25 April 2012) http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2012/04/19/tobaccocontrol-2011-050147. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davis R, Loken B, Gilpin E, Viswanath K, Wakefield M, editors. National Cancer Institute. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco UseTobacco Control Monograph. Vol. 19. US Dept. of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2008. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015]. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/19/m19_complete.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Network of African Science Academies. Preventing a tobacco epidemic in Africa: a call for effective action to support health, social, and economic development, Nairobi, Kenya. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015];Report of the Committee on the Negative Effects of Tobacco on Africa’s Health, Economy, and Development. 2014 http://www.nationalacademies.org/asadi/Africa%20To-bacco%20Control-FINAL.pdf.

- Njoumemi Z, Sibetcheu D, Ekoe T, Gbedji E. Cameroon. In: Drope J, editor. Tobacco Control in Africa: People, Politics and Policies. Chapter 8. Anthem Press and International Development Research Centre; London, UK: 2011. [Last accesses on November 09, 2015]. http://idl-bnc.idrc.ca/dspace/bitstream/10625/47373/1/IDL-47373.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sala-i-Martin X, Pinkovskiy M. African poverty is falling…much faster than you think! National Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. [Last accesses on November 09, 2015]. Working Paper Series. 15775 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15775. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: 2015. United Nations Treaty Collection. 21 May 2003 Available at https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IX-4&chapter=9&lang=en. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015];World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision, Volume I: Comprehensive Tables. 2011 ST/ESA/SER.A/313. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/trends/WPP2010/WPP2010_Volume-I_Comprehensive-Tables.pdf.

- WHO FCTC News. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Media Centre WHO FCTC news; 2015. [Last accessed on May 04, 2015]. Pictorial health warnings gain ground in Africa. http://www.who.int/WHOFCTC/mediacentre/news/2015/africapictorial/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Switzerland, Geneva: 2003. [Accessed on July 5, 2015]. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241591013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER Package. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [Accessed on November 09, 2015]. http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/mpower_report_full_2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013: Enforcing Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85380/1/9789241505871_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2014 Global Progress Report on Implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva Switzerland: 2014. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015]. http://www.who.int/WHOFCTC/reporting/2014globalprogressreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO FCTC. The World Health Organization; 2015a. Jan, [Last accessed on November 09, 2015]. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: an overview. Available at: http://www.who.int/WHOFCTC/WHO_WHOFCTC_summary_January2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. MPOWER Brochures and Other Resources. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015b. [accessed on 8 July 2015]. p. 2015. http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/publications/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015: raising taxes on tobacco. World Health Organization; Geneva. Switzerland: 2015c. [Last accessed on November 09, 2015]. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2015/report/en/ [Google Scholar]