Abstract

Absorbable plates are used widely for fixation of facial bone fractures. Compared to conventional titanium plating systems, absorbable plates have many favorable traits. They are not palpable after plate absorption, which obviates the need for plate removal. Absorbable plate-related infections are relatively uncommon at less than 5% of patients undergoing fixation of facial bone fractures. The plates are made from a mixture of poly-L-lactic acid and poly-DL-lactic acid or poly-DL-lactic acid and polyglycolic acid, and the ratio of these biodegradable polymers is used to control the longevity of the plates. Degradation rate of absorbable plate is closely related to the chance of infection. Low degradation is associated with increased accumulation of plate debris, which in turn can increase the chance of infection. Predisposing factors for absorbable plate-related infection include the presence of maxillary sinusitis, plate proximity to incision site, and use of tobacco and significant amount of alcohol. Using short screws in fixating maxillary fracture accompanied maxillary sinusitis will increase the rate of infection. Avoiding fixating plates near the incision site will also minimize infection. Close observation until complete absorption of the plate is crucial, especially those who are smokers or heavy alcoholics. The management of plate infection is varied depending on the clinical situation. Severe infections require plate removal. Wound culture and radiologic exam are essential in treatment planning.

Keywords: Absorbable implants, Facial injuries, Infection

INTRODUCTION

The choice of fixation is an important consideration in the management of facial bone fractures. Traditionally, titanium plates have been used for fixation of most facial bone fractures, as these metal plates allow for rigid fixation with low rates of infection. Common complaints for titanium fixation includes palpability, visibility of plate outline, sensitivity to temperature, metal allergy, secondary infection, bone resorption, and the possibility of interference with postoperative radiologic assessments. In addition, titanium plates do not accommodate for bone growth in younger patients. For this reason, absorbable plates are finding more use in the fixation of fractured facial bones [1,2,3,4,5]. Studies have demonstrated that absorbable plate fixation can provide stability and strength that is comparable to those of titanium plate fixations [6,7]. Spontaneous resorption of the plate material is the main advantage of using absorbable plates, as this significantly decreases the need for plate removal [5,8].

The main concern with absorbable plate is the risk of infection [9]. Common symptoms and signs are swelling, pain, tenderness, wound dehiscence, and purulent discharge at the site of internal fixation. Such sign of infection can develop well over a year after plate implantation (Fig. 1) [10]. In this paper, we review infections following fixation of facial bone fracture using absorbable plates.

Fig. 1. (A) This 48-year-old patient presented with a rapidly developing right facial swelling 13 months after undergoing zygomatic reduction using absorbable plates. (B) Postoperative appearance at 8 months after surgery showing no evidence of swelling. (C) This 45-year-old patient presented with swelling and redness of the right orbital region 6 months after absorbable plate fixation of the infraorbital rim. (D) The symptom subsided after 6 months of removal of partially resorbed plates and screws.

INFECTION RATE

On the topic of infection rate following absorbable plate fixation, a recent study has reported just a single case of plate infection out of 59 zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture patients [1]. In a similar study involving pediatric facial fractures, no infection had occurred across 44 cases [11]. In a more comprehensive study comparing infection rates between titanium and absorbable plates in 91 mandible fracture cases, two out of 47 patients (4.26%) with absorbable plates had infection, whereas one out of 44 patients (2.27%) with titanium plates showed infection [2].

Most studies have reported infection rate at less than 5 % in patients with absorbable plates, and most of these studies had been reported for mandible fractures fixated with absorbable plates. Data regarding other types of facial fractures are lacking. Tobacco use was associated with higher infection rate, as was the case for heavy alcohol use [12].

PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF ABSORBABLE PLATES

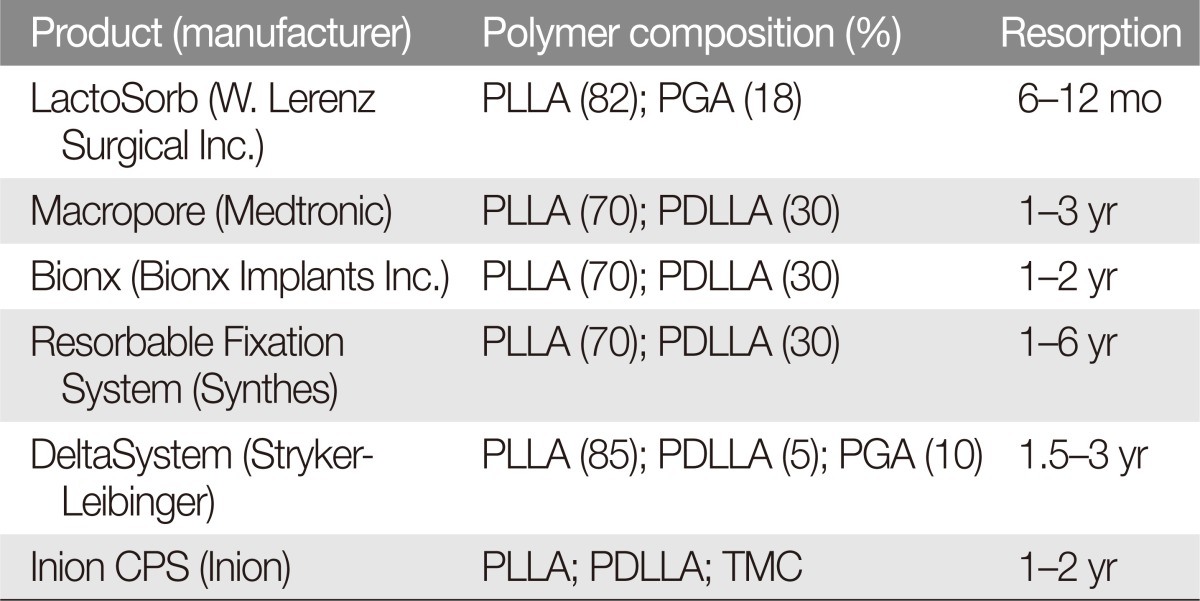

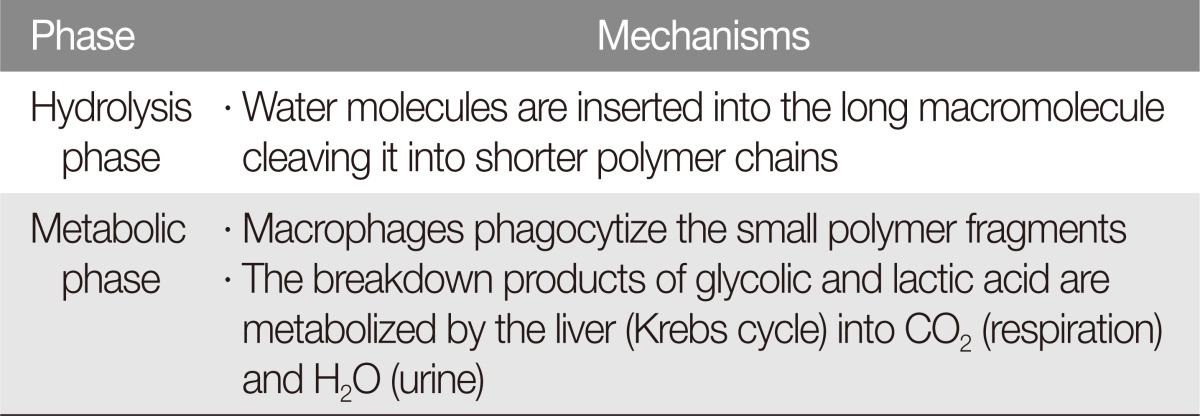

Absorbable plates are composed of macromolecular chains which form a single polymer. Polymers used for absorbable plates can include polylactic acid, polyglycolic acid, polyglyconate, and polydioxanone. Among these, polylactic acid and polyglycolic acid are the most widely used. Polyglycolic acid is absorbed within a month and is a crystalline polymer with considerable flexural strength. Polylactic acid has two isomeric configurations, poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) and poly-DL-lactic acid (PDLLA). Of the two isomers, absorbable plates made from PLLA have greater strength but takes five to six years for absorption. In contrast, PDLLA is mechanically less rigid but is resorbs within a year. Today, absorbable plates are made with varying ratios of PLLA and PDLLA or PDLLA and polyglycolic acid, to create mechanically sound fixation plates which are absorbed within nine months to three years (Table 1). Biodegradation of absorbable plate consists of two sequential phases: the hydrolysis phase and the metabolic phase. In the hydrolysis phase, water molecules penetrate into the absorbable plates which will start the degradation of long macromolecules into shorter polymeric chains. The individual polymeric chains are phagocytized by the macrophage and moved to the liver for metabolism. In the metabolic phase, the individual macromolecules are degraded into carbon dioxide and water (Table 2) [3,4,8].

Table 1. Commercially available resorbable plating system.

PLLA, poly-L-lactic acid; PGA, poly glycolic acid; PDLLA, poly-DL-lactic acid; TMC, trimethylene carbonate.

Table 2. The biodegradation phases of bioresorbable plates.

Dynamic strength will be maintained for three to four months [10]. Even if a plate remains unabsorbed, its tensile strength is weakened after four months [1,11]. Inflammation may occur if the degradation rate is higher than that of the body's ability to clear the metabolites or if too many debris particles remain beyond time needed for wound healing. Therefore, gradual degradation is a key physical property needed to ensure that an absorbable plate does not incite unnecessary inflammation [4,12].

COMMON CAUSE OF INFECTION

Absorbable plate-related infection may occur through a number of mechanisms. If an implanted plate is close to the incision site, the short surgical dissection tract give external pathogens a chance to invade and colonize the implant site. Patients with history of maxillary sinusitis prior to facial skeletal operations are more likely to develop plate infection, as fixation screws penetrating into the anterior wall of the maxilla will allow communication between the sinus and the plate [13].

In patients with mandibular fractures, absorbable plate infection usually occurs a year after the operation. In such patients, infections are associated with sub mucosal plates which did not undergo resorption even after the bone union. Complete absorption of plate requires at least nine months to three years, and infection is always possible unless these plates are completely absorbed [5].

PREVENTION

Recent evaluation of prevention strategies have addressed operative factors that can influence those sources of infection mentioned above. In patients with facial fracture and maxillary sinusitis, the use of shorter screws (less than 4 mm) has been found to prevent penetration of the screw tip into the maxillary sinus, which in turn decreases the chance of bacterial translocation from the sinus to the plate.

Placing surgical incision away from fracture lines is another strategy to decrease the risk of infection, and this is especially applicable for those patients with thinner dermis. If the plate is or becomes exposed, immediate coverage is critical. Titanium plate fixation may be considered if the plate is close to the incision site or if the patient has sinusitis or other source of infection [13,14,15,16,17,18].

During the follow up period, patients who use tobacco or drink heavily require more close attention. Patients should be followed for three years or until plates have undergone complete resorption.

TREATMENT

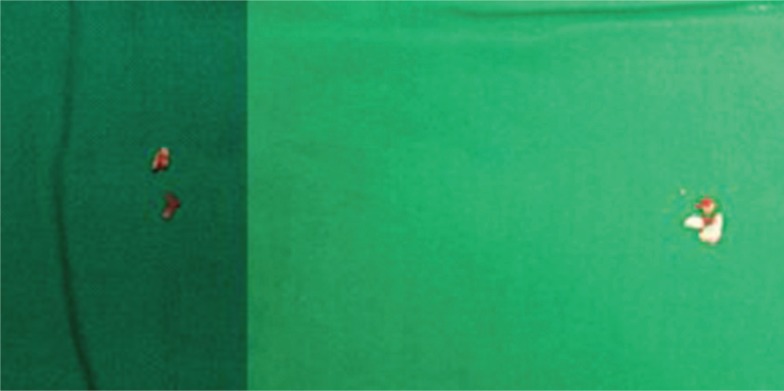

Absorbable plate-related infection are treated in the following manner. If the signs and symptoms suggest mild-to-moderate infection, the situation might be salvaged with incision and drainage along with intravenous antibiotics. However, severe or recurrent infections most likely require surgical removal of the plate which has yet to undergo resorption (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Partially resorbed plates and screws that were taken out from the surgical removal.

Wound culture is essential for choosing appropriate antibiotics. Serial radiologic exams or computed tomography scan are needed for evaluation of sinusitis after maxillofacial fracture operation. If the maxillary sinusitis is the source of infection, plate removal is strongly recommended. Infections restricted to incision site can often be managed with incision and drainage plus intravenous antibiotic [14]. In a recent study on the rate of plate removal, absorbable plates had removal rates of 2% to 3%, which compares favorably to the reported rate of 12% for titanium plates. However, the cause of removal is mostly infection or nonunion for absorbable plates, whereas titanium plates are usually removed because of exposure or palpability [5].

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Bell RB, Kindsfater CS. The use of biodegradable plates and screws to stabilize facial fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee HB, Oh JS, Kim SG, Kim HK, Moon SY, Kim YK, et al. Comparison of titanium and biodegradable miniplates for fixation of mandibular fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2065–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imola MJ, Hamlar DD, Shao W, Chowdhury K, Tatum S. Resorbable plate fixation in pediatric craniofacial surgery: long-term outcome. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:79–90. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.3.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Losken HW, van Aalst JA, Mooney MP, Godfrey VL, Burt T, Teotia S, et al. Biodegradation of Inion fast-absorbing biodegradable plates and screws. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:748–756. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31816aab24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal S, Gupta A, Grevious M, Reid RR. Use of resorbable implants for mandibular fixation: a systematic review. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:331–339. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31819922fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yerit KC, Enislidis G, Schopper C, Turhani D, Wanschitz F, Wagner A, et al. Fixation of mandibular fractures with biodegradable plates and screws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:294–300. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.122833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gosain AK, Song L, Corrao MA, Pintar FA. Biomechanical evaluation of titanium, biodegradable plate and screw, and cyanoacrylate glue fixation systems in craniofacial surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:582–591. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuncer S, Yavuzer R, Kandal S, Demir YH, Ozmen S, Latifoglu O, et al. Reconstruction of traumatic orbital floor fractures with resorbable mesh plate. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:598–605. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000246735.92095.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollier LH, Rogers N, Berzin E, Stal S. Resorbable mesh in the treatment of orbital floor fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12:242–246. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Chang JW, Choi MS, Ahn HC. Delayed infection after a zygoma fracture fixation with absorbable plates. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:2018–2019. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f5387c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eppley BL. Use of resorbable plates and screws in pediatric facial fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittwer G, Adeyemo WL, Yerit K, Voracek M, Turhani D, Watzinger F, et al. Complications after zygoma fracture fixation: is there a difference between biodegradable materials and how do they compare with titanium osteosynthesis? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon H, Kim SW, Jung SN, Sohn WI, Moon SH. Cellulitis related to bioabsorbable plate and screws in infraorbital rim fracture. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:625–627. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182085541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi HJ, Kim W, Youn S, Lee JH. Management of delayed infection after insertion of bioresorbable plates at the infraorbital rim. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:524–525. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cd4de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park CH, Kim HS, Lee JH, Hong SM, Ko YG, Lee OJ. Resorbable skeletal fixation systems for treating maxillofacial bone fractures. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:125–129. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degala S, Shetty S, Ramya S. Fixation of zygomatic and mandibular fractures with biodegradable plates. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2013;3:25–30. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.110072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song SW, Burm JS, Yang WY, Kang SY. Microplate fixation without maxillomandibular fixation in double mandibular fractures. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2014;15:53–58. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2014.15.2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim TH, Yang IH, Minn KW, Jin US. Use of a y-shaped plate for intermaxillary fixation. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2015;16:96–98. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2015.16.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]