Abstract

Polyotia is an extremely rare type of the auricular malformation that is characterized by a large accessory ear. A 3-year-old girl presented to us with bilateral auricular abnormalities and underwent two-stage corrective operation for polyotia. In this report, we present the surgical details and postoperative outcomes of polyotia correction in the patient. Relevant literature is reviewed.

Keywords: Ear auricles, Congenital abnormalities, Matriderm

INTRODUCTION

Polyotia is an external ear malformation that is characterized by a large accessory ear, and is a clinical entity distinct from a pre-auricular tag [1]. It is an extremely rare condition; to date, less than 30 cases of polyotia have been reported according to a review of the literature [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In this report, we present the surgical details and postoperative outcomes of polyotia correction in a 3-year-old girl, along with relevant review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 3-year-old girl presented with bilateral auricular anomalies after birth. She was born after a normal course of pregnancy as a full-term baby and did not have any notable family history related to developmental abnormalities or congenital malformations. The child had met the usual developmental milestones, including verbal and hearing functions.

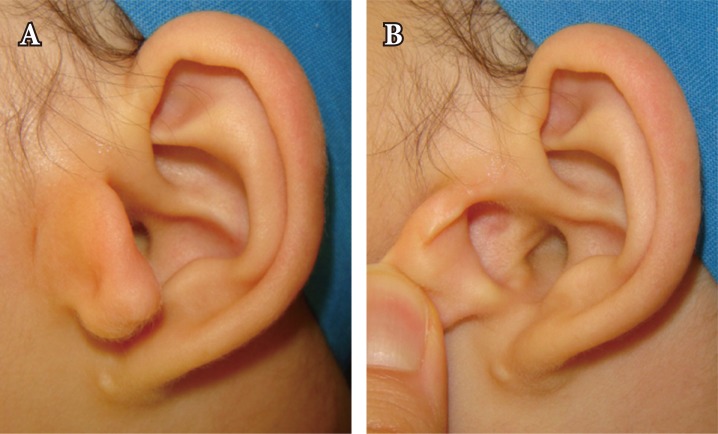

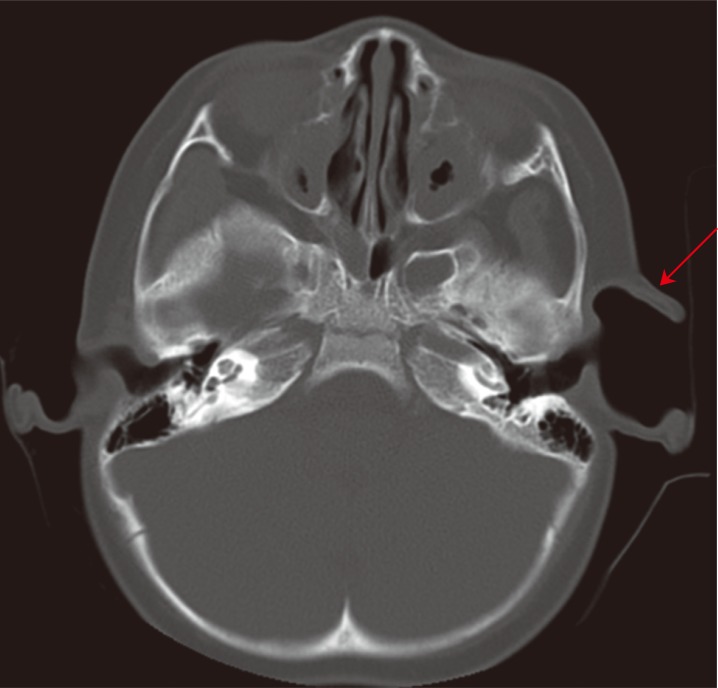

Physical examination was significant for left-deviated asymmetry of mandibular and facial midline. The patient had a 1×1 mm pre-auricular tag that was located anterior and inferior to the tragus. The left external ear had a large accessory auricle in the pre-tragal area (Fig. 1A). This accessory auricle had a well-formed helix and a conchal cavity composed of the cartilage, with a depression that mirrored cavum concha along the longitudinal axis of external ear (Fig. 1B). The helical crus of accessory ear was continuous with a normal posterior auricle, which had normal helix, antihelix, and antitragus. Despite the malformation, the left ear was positioned at the same level as the contralateral auricle, with anteroposterior view of the normal auricles being fairly symmetric. Laboratory examination and pure tone audiometry were within normal limits. Facial computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the deformity to be confined to the external ear, with normal ear canal, and also identified hypoplasia of left mandibular ramus and condyle (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Preoperative photographs of the polyotic ear in the 3-year-old patient. (A) The anterior accessory auricle is rather large. (B) Anterior retraction of the accessory auricle reveals an anterior cavum that mirrors the normal, posterior cavum.

Fig. 2. Preoperative axial computed tomography scan of the patient demonstrates a significant preauricular hollowness deep to the anterior auricle (red arrow).

At age 3, the patient underwent first operation. At that time, the right pre-auricular skin tag was resected and skin closed primarily. The left ear was addressed by excision of the redundant skin and burying of the extra cartilage. The skin was closed primarily over this (Fig. 3). Postoperative course was uneventful, and the wound healed well during the follow-up period. Definitive reconstructive operation was delayed until development of external was complete.

Fig. 3. Immediate photograph after first operation. At this point, the extra cartilage is folded and buried deep to the closed skin.

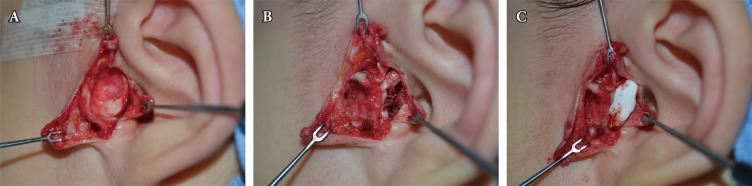

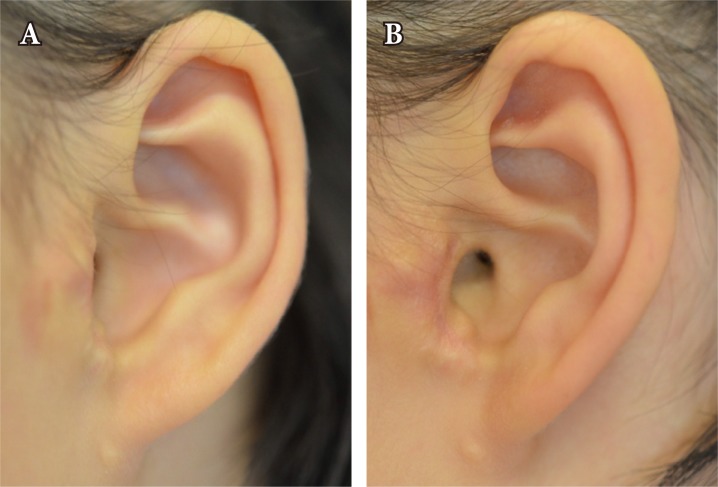

At 6 years of age, the child underwent secondary operation to address the helix-like cartilaginous framework within the deep pre-tragal hollow space (Fig. 4). The incision was made along the inner margin of accessory helix, the junction of the helical crus between the accessory ear and the posterior auricle, and along the anterior margin of hypoplastic tragus. The skin was elevated from the cartilaginous framework (Fig. 5A). The prominent helical and pre-tragal cartilages were prepared by scoring and wrapping. The resulting shape was retained with a purstring suture (4-0 vicryl) and subsequently fixed to hypoplastic tragus, with the two primary goals of filling the pre-tragal hollowness and creating a new tragus (Fig. 5B). The pre-tragal hollowness was further filled using dermal substitute graft (Matriderm, Medskin solutions, Billerbeck, Germany) (Fig. 5C). The redundant skin was tailored to drape the newly constructed tragus, and the wound was closed without tension. Postoperative course was uneventful. Postoperative appearance of the left ear was improved, with a more normal pre-tragal contour (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4. Preoperative photograph just prior to second operation. The auditory meatus is marked with red star. Hypoplastic tragus is notable.

Fig. 5. Photographs during the second operation. (A) Skin dissection reveals the underlying cartilaginous framework. (B) The cartilage was deconstructed and rearranged to fill the empty space. (C) Dermal substitute was used to further fill the space and to reconstruct the tragus.

Fig. 6. (A, B) Photograph of the left ear 12 months after second operation.

DISCUSSION

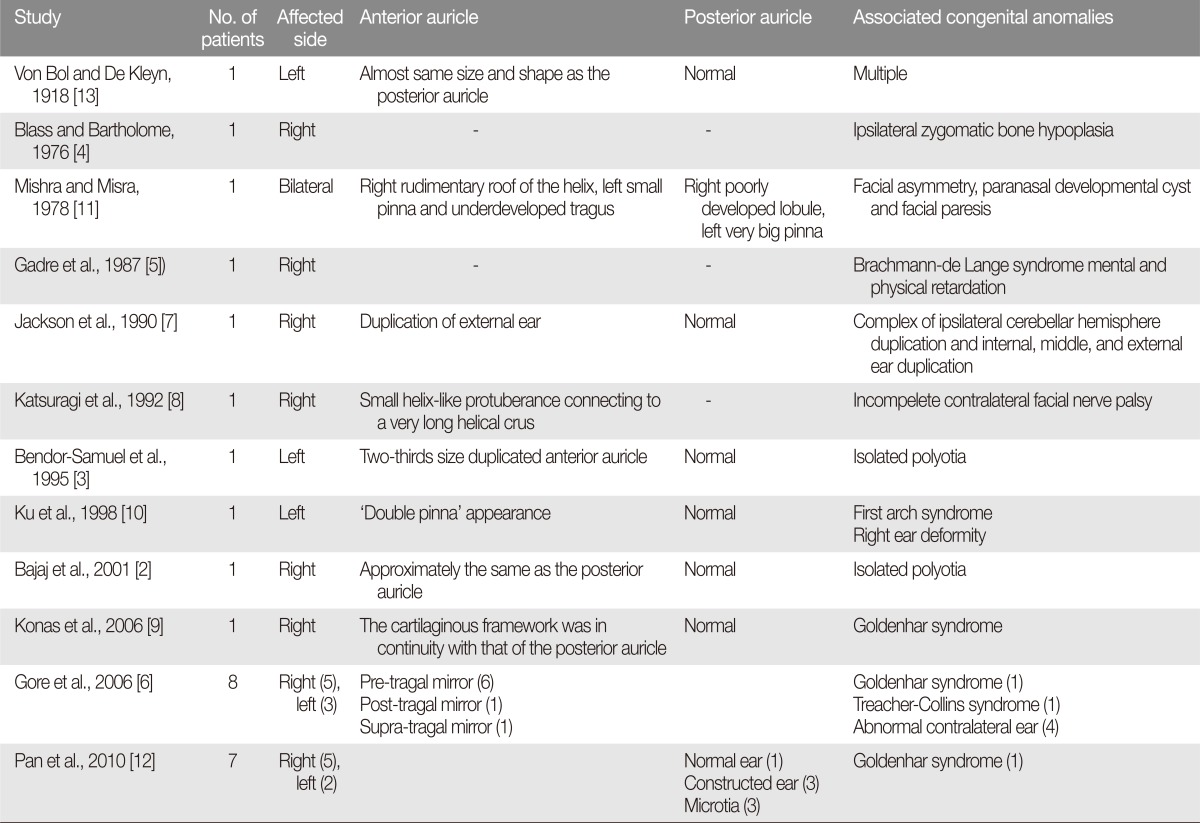

Polyotia was first reported in 1918 by Von Bol and De Kleyn [13] who described left polyotia in a child with multiple congenital anomalies (Table 1). The size and shape of anterior auricle was reported to be as large as the normal posterior auricle, and the size of the anterior auricle came to be the key clue in differentiating polyotia and skin tag [6]. Posterior to the accessory auricle, the auricle in the correct position can be normal, constricted, or microtic. Because of this symmetry along the coronal plane between the anterior and posterior auricles, the condition is sometimes referred to as mirror ear [12]. To date, many hypotheses have been proposed to explain the etiology of polyotia, with abnormal migration of neural crest cell (NCC) considered the most plausible of mechanisms [6,12]. Retinoic acid embryopathy has been known to cause embryological abnormalities, greatly affecting the migration of NCC. Lammer [14] demonstrated that patients with fetal exposure to retinoic acid had an increased risk of developing external ear defects including partial duplications.

Table 1. A summary of literature on polyotia.

Polyotia is frequently associated with contralateral ear abnormalities and other congenital anomalies. According to our review of 12 published polyotia reports, 15 patients with polyotia also had concurrent congenital anomalies, as was the case in our patient who had mandibular hypoplasia (Table 1).

Polyotia correction is dependent on the posterior auricle, which is classified as having normal, constricted, or microtic posterior auricle by Pan et al. [12]. These authors performed free auricular composite tissue grafting for patients with constructed ear. Microtic posterior auricle was reconstructed using tissue expander and autogenous rib cartilage. The accessory ear was used to form the tragus of reconstructed ear.

In our case, our patient had an accessory ear with the underdeveloped tragus. This anterior portion of the external ear was deconstructed at the first operation. The excess cartilage was folded and buried deep to the subcutaneous tissue to prevent growth disturbance to the normal portion of the outer ear-the posterior auricle. The second operation was withheld until 6 years of age, and at this point, the extra cartilage and dermal substitute was used to both fill in the hollowness and to construct the neo-tragus.

Because polyotia is extremely rare, it is most likely diagnosed as a large pre-auricular skin tag in many cases. However, surgical management differs vastly between pre-auricular skin tag and polyotia. Skin tags are relatively easy to manage with careful dissection of the skin and simple excision of the redundant tissue. However, polyotia requires deconstruction and repositioning of the cartilaginous framework in order to facilitate the construction of tragal features. In this report, we have reported a successful correction of polyotia using extraneous tissue and dermal substitute.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Marx H. Die Mibildungen des ohres. Handbuch der Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heikulde. 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajaj Y, Sahni JK, Jain A, Kansal Y. Polyotia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:75–77. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendor-Samuel RL, Tung TC, Chen YR. Polyotia. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34:650–652. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199506000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blass K, Bartholome W. True polyotia, a rare anomaly of early foetal development (author's transl) Hno. 1976;24:309–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadre AK, Patil DP, Iyer U, Prasad S. Duplication of the pinna (polyotia) in a case of Brachmann-de Lange syndrome. Br J Plast Surg. 1987;40:642–644. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(87)90161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gore SM, Myers SR, Gault D. Mirror ear: a reconstructive technique for substantial tragal anomalies or polyotia. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JM, Sadove AM, Weaver DD, Edwards MK, Bull MJ. Unilateral duplication of the cerebellar hemisphere and internal, middle, and external ear: a clinical case study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:550–553. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199009000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katsuragi M, Kojima T, Shimbashi T. Polyotia: a case report. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 1992;24:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konas E, Canter HI, Mavili ME. Goldenhar complex with atypical associated anomalies: is the spectrum still widening? J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:669–672. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200607000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ku PK, Tong MC, Yue V. Polyotia: a rare external ear anomaly. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;46:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(98)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra SC, Misra M. Mirror image pinna. J Laryngol Otol. 1978;92:709–711. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100085984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan B, Qie S, Zhao Y, Tang X, Lin L, Yang Q. Surgical management of polyotia. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:1283–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Von Bol G, De Kleyn A. Uber einen fall von polyotie. Acta Otolaryngol. 1918;1:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lammer E. Preliminary observations on isotretinoin-induced ear malformations and pattern formation of the external ear. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1991;11:292–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]