Abstract

Client engagement in services is a critical element of effective community-based child and family mental health service delivery. Caregiver engagement is particularly important, as caregivers often serve as gatekeepers to child mental health care and typically must consent for services, facilitate service attendance, and are often the target of intervention themselves. Unfortuntately, caregiver engagement has been identified as a significant challenge in community-based child mental health services. To address this gap, the Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit (PACT), which includes therapist training and participation tools for caregivers and therapists, was developed. Stakeholders’ perspectives regarding the delivery of interventions designed to improve the quality and effectiveness of community-based care are essential to understanding the implementation of such interventions in routine service settings. As such, this mixed methods study examined the perspectives of 12 therapists, eight caregivers, and six program managers who participated in a community-based randomized pilot study of PACT. Therapists, caregivers, and program managers agreed that PACT was acceptable, appropriate, and feasible to use in community settings and that both changes in therapist practices and caregiver participation resulted from implementing PACT. Some variable perceptions in the utility of the therapist training components were identified, as well as barriers and facilitators of PACT implementation. Results expand the parent pilot study’s findings as well as complement and expand the literature on training community providers in evidence-based practices.

Keywords: Multiple stakeholder perspectives, community mental health clinics, caregiver participation, mixed methods, evidence-based practice

Client engagement in services is a critical element of effective community-based child and family mental health service delivery (e.g., Staudt, 2007). Caregiver engagement is particularly important given caregivers often serve as gatekeepers to their children’s mental health care and typically must consent for services, facilitate service attendance, and are often the target of intervention themselves. Furthermore, caregiver engagement in services has been linked to improvements in child outcomes (Dowell & Ogles, 2010; Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015; Karver, Handelsman, Fields, & Bickman, 2006) and is considered an important process for improving the overall quality of community-based care (Garland et al., 2013).

Caregiver engagement can also be considered an “evidence-based process” (Huang et al., 2005) as it is a foundation of multiple evidence-based practices (EBPs) across many child and adolescent mental health disorders. Specifically, caregivers are the focus of most EBPs for disruptive behaviors (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Evans, Owens, & Bunford, 2014), which are the most common disorders in community-based child mental health care settings (Garland et al., 2001). In addition, caregivers are often a focus of treatment for EBPs targeting depression (e.g., David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008), anxiety (e.g., (Silverman, Pina, & Viswesvaran, 2008), self-injurious behaviors (Glenn, Franklin, & Nock, 2015), bipolar disorder (Fristad & MacPherson, 2014), and substance abuse (Hogue, Henderson, Ozechowski, & Robbins, 2014), although intensive caregiver engagement may not always be indicated (e.g., treatment of adolescent depression). It is also important to note that clients contribute to successful protocol fidelity, suggesting that caregiver engagement may impact therapists’ ability to deliver EBPs with fidelity (Allen, Linnan, & Emmons, 2012; Perepletchikova & Kazdin, 2005; Schoenwald, Sheidow, Letourneau, & Liao, 2003).

Attendance is the most commonly used indicator of caregiver engagement (Becker et al., 2015; Ingoldsby, 2010); however, engagement also consists of active participation in treatment, including both meaningful interactions in sessions and follow-through with treatment recommendations between sessions (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015; Nock & Ferriter, 2005; Staudt, 2007). Participation engagement reflects the caregivers’ active, independent, and responsive contributions to treatment rather than the relationship between caregiver and therapist, and thus is distinct from working alliance (Shirk & Saiz, 1992; Tetley, Jinks, Huband, & Howells, 2011).

Caregivers and child clients served in community settings both report a strong desire for greater caregiver participation in treatment (Baker-Ericzén, 2013; Flynn, 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2014). Studies have documented that community-based therapists are not optimally attending to caregiver participation in treatment for underserved, culturally diverse families (Baker-Ericzén, Jenkins, & Haine-Schlagel, 2013; Garland et al., 2010; Haine-Schlagel, Brookman-Frazee, Fettes, Baker-Ericzén, & Garland, 2012). For example, one observational study found that therapists included the caregiver in session activities less than half the time, with significant variability across providers (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2012). Studies also indicate that therapists rarely assign or review homework in their practice (Garland et al., 2010), and inconsistently involve caregivers in decision making about treatment (Baker-Ericzén et al., 2013).

Community-based child therapists serving culturally diverse families have identified several barriers to engaging caregivers in treatment. For example, therapists feel overwhelmed by caregivers’ and families’ needs and frustrated by some caregivers’ apparent lack of interest in or ability to participate in treatment (Baker-Ericzén, 2013; Rodriguez, Southam-Gerow, O’Connor, & Allin, 2014). Moreover, therapists identify lack of time and work load as major barriers to focusing on engaging caregivers in their services (Staudt, Lodato, & Hickman, 2011). A lack of training on how to meaningfully involve caregivers in their children’s treatment may also be a challenge (Brookman-Frazee, Drahota, Stadnick, & Palinkas, 2012). To date no study has examined program manager perspectives on challenges engaging families.

Both community-based therapists and caregivers have identified family-level barriers to engagement. From therapists’ perspective, caregivers’ attitudes and beliefs about treatment and the mental health system, as well as the complex needs of both the caregivers and children, contribute to challenges in engaging caregivers in treatment (Baker-Ericzen et al., 2013; Staudt et al., 2011). Caregivers report feeling unsupported by the system and blamed and ignored by therapists, which can impact motivation to engage in treatment (Baker-Ericzen et al., 2013). In addition, quantitative studies have identified family-level barriers to engaging in services, such as a racial/ethnic minority background and caregiver mental health problems (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015).

Therapeutic strategies to increase caregiver and client engagement, most commonly treatment attendance, have been developed and some have promising efficacy and/or effectiveness data in community-based settings (Becker et al., 2015; Ingoldsby, 2010). The majority of these interventions focus exclusively on early sessions and on increasing attendance at sessions, rather than focusing caregivers’ active participation in ongoing treatment. A small group of caregiver-focused interventions have also been developed to improve caregivers’ motivation and skills to participate in community-based care (e.g., Rodriguez et al., 2011). However, optimal effectiveness of existing strategies is reduced given their sole focus on either the caregiver or the therapist. Models for targeting both stakeholders simultaneously to help them effectively collaborate together have been identified as an important next step in the development of strategies to increase client participation in community-based services (Cortes, Mulvaney-Day, Fortuna, Reinfeld, & Alegría, 2009; Polo, Alegría, & Sirkin, 2012).

The Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit (PACT)

To address both the need for tools to increase caregiver participation in ongoing treatment and the need for strategies that target both therapists and caregivers simultaneously, the Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit (PACT; Haine-Schlagel & Bustos, 2013) was developed. PACT is designed for children ages 4–13 with disruptive behavior problems, a client group commonly served in community-based treatment and for which caregiver involvement is clinically indicated (Garland, Hough, McCabe, Yeh, Wood, & Aarons, 2001; Garland, Hawley, Brookman-Frazee, & Hurlburt, 2008).

PACT is not a treatment protocol, but rather a services toolkit designed to complement standard community-based care. The toolkit includes five tools (see Haine-Schagel, Martinez, Roesch, Bustos, & Janicki, 2016 for more detail): a set of evidence-based engagement strategies for therapists to implement in all clinical contact with caregivers (referred to as the “ACEs” given their focus on Alliance, Collaboration, and Empowerment); a DVD with stakeholder testimonials and an accompanying workbook (both for caregivers); a worksheet for therapists and caregivers (and children when applicable) to facilitate collaborative homework planning across sessions (referred to as the “Action Sheet”); and motivational messages sent to caregivers between sessions. PACT’s therapist and caregiver tools are linked. For example, PACT includes both training for therapists to encourage opportunities for caregivers to ask questions and DVD and workbook sections that encourage caregiver to ask the therapist any questions the caregiver may have. The goal of PACT is not to add family therapy to individual psychotherapy (no family therapy training is provided) but rather to encourage the treatment to directly involve the caregiver, which may include (but is not limited to) strategies for the caregiver to support the child’s individual work, parent training, and/or family therapy. The PACT training package is delivered concurrent with therapist utilization of the toolkit, and includes an in-person workshop, eight interactive group webinar consultations, one individual consultation with a PACT trainer, and weekly training tips.

The toolkit utilizes the Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB; Jaccard, Dodge, & Dittus, 2002; Olin et al., 2010) as its organizing framework for behavior change targets. The UTB proposes factors that determine a person’s intention to perform a behavior (e.g., attitudes such as motivation, social norms, expected benefits) as well as factors that impact the likelihood that intention leads to the behavior being performed (e.g., knowledge, skills, opportunity; Jaccard et al., 2002; Olin et al., 2010). This framework has been applied to the development of services for diverse families (e.g., Olin et al., 2010). In addition, PACT draws from many effective engagement strategies from mental health services engagement interventions focused on initial service delivery and attendance, such as targeted assessment, promoting caregiver input and questions, supporting caregiver efficacy, and attention to homework (e.g., Alegría et al., 2008; Becker et al., 2015; Hoagwood et al., 2010; Mah & Johnston, 2008; McKay, McCadam, & Gonzales, 1996; McKay, Nudelman, McCadam, & Gonzales, 1996; McKay, Stoewe, McCadam, & Gonzales, 1998; Nock, & Kazdin, 2005; Olin et al., 2010). PACT also integrates strategies from the broader services engagement research (e.g., links between text messaging and enhanced engagement and outcomes; Carta, Lefever, Bigelow, Borkowski, & Warren, 2013; Murray, Woodruff, Moon, & Finney, 2015). Community stakeholders (youth, caregivers, therapists, program managers, and program support staff) provided input throughout the creation of the toolkit’s materials and training, including participating in surveys, interviews, focus groups, and providing testimonials. In addition, a small group of community-based therapists and families conducted a feasibility pilot of an earlier version of the toolkit. The families and therapists who participated in these developmental activities were culturally diverse (e.g., 86% of caregivers who participated in toolkit development interviews and focus groups were from a racial/ethnic minority background; 63% of participants who provided testimonials for the DVD were from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds). In addition, consultation with a services researcher with expertise in cultural diversity was obtained throughout the development process to maximize the toolkit’s relevance for a diverse range of families (e.g., the DVD includes reference to concerns some racial/ethnic minority caregivers may have about whether asking their child’s therapist questions may be a sign of disrespect).

Previously analyzed quantitative data from a recent randomized controlled pilot study support the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of PACT when utilized in community mental health clinics (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2016). Specifically, therapists randomized to use PACT participated in ongoing PACT training, utilized PACT as intended based on video observations, and reported overall positive perceptions of PACT in feedback surveys. Pilot study results also indicate that therapists trained in PACT demonstrated improvements in their job attitudes and their actual use of caregiver engagement strategies with their PACT family compared to therapists in the standard care condition. In addition, PACT families tended to attend sessions more regularly and demonstrated some increased caregiver participation behaviors in sessions compared to the standard care condition. Results also demonstrated some indication of differences in caregivers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of treatment, with PACT families reporting somewhat greater perceived effectiveness.

The Current Study

The primary goal of the current study is to build upon a previous evaluation of PACT (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2016) to further examine the toolkit’s implementation outcomes (Proctor et al., 2011), barriers and facilitators to PACT implementation, and PACT perceived effectiveness. Such information is critical to allow for refinement of the toolkit to improve its implementation and sustainment in community settings (Garland, Kruse, & Aarons, 2003; Hoagwood, Burns, Kiser, Ringheisen, & Schoenwald, 2001). To accomplish this goal, the current study utilizes a mixed-methods approach to examine the perspectives of three stakeholder groups who participated in the pilot study, therapists, caregivers, and program managers, on the training, delivery, and outcomes of PACT. These data were collected to complement and expand the initial feasibility and preliminary effectiveness data (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2016). Since PACT was developed based on feedback from therapists, caregivers, and program managers, it was hypothesized that all groups would consider PACT to be acceptable, appropriate, and feasible to use in community settings, which are key implementation outcomes (Proctor et al., 2011), and that stakeholders would perceive PACT as effective in changing therapist and caregiver behaviors. Further, it was expected that stakeholders’ quantitative and qualitative responses would complement each other when both were available.

Method

Design

Data for the current study were drawn from the parent pilot study of PACT and corresponding therapist training protocol. To capture the depth and potential diversity of stakeholders’ perceptions about their experiences with PACT’s therapist training and implementation, the current study utilized both qualitative interviews and quantitative survey data to examine themes among and across stakeholder groups. Mixed method designs combine qualitative and quantitative results to better understand research issues compared to either approach alone (Palinkas, 2014). Qualitative and quantitative data are used to determine convergence, complementarity, or comparison across results (Palinkas, 2014).

Participants

Participants were drawn from five community mental health clinics within three large organizations that serve a sizable, geographically diverse county within California. These clinics contract with the county’s behavioral health services department to provide services to racially/ethnically and diagnostically diverse children and their families who are publicly insured or uninsured. Study participants included 12 therapists and eight caregivers from their caseloads who participated in the PACT condition of the parent randomized pilot study, as well as six program managers who oversaw the participating clinics. These sample sizes are adequate based on previous research that metathemes can be present with as few as six interviews and saturation can occur within twelve interviews (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006).

PACT pilot study therapist participants

Therapists in the current study represented the group of therapists from the parent pilot study who were randomly assigned to deliver PACT in the context of standard care (versus random assignment to a standard care alone condition). All therapists from six community mental health clinics were recruited through weekly treatment team/supervision meetings between August and December, 2013 (therapists from five clinics participated in the study). Of the 71 therapists present during recruitment meetings, 83% (n=59) agreed to be contacted about the study. Therapists were eligible if they: a) were employed at their agency for at least the next five months, b) provided clinic-based psychotherapy to children and their families, and c) available to start a new episode of care with an eligible caregiver-child dyad during the recruitment window. Thirty-one therapists from five clinics were randomized to either PACT or standard care conditions (n=16 and n=15, respectively). Four therapists withdrew from the PACT condition due to workload demands. The remaining 12 PACT therapists comprised the therapist sample for current analyses. See Table 1 for therapist participant demographic information. Consistent with national and local samples of community-based therapists (e.g., Brookman-Frazee, Garland, Taylor, & Zoffness, 2009; Glisson et al., 2008), most therapists held Masters-level degrees (83.3%) and were unlicensed (83.3%).

Table 1.

Participant demographics by study condition.

| Therapists (n=12) n (%) |

Caregivers (n=8) n (%) |

Program Managers (n=6) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 2 (16.7) | 0 0.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Female | 10 (83.3) | 8 (100.0) | 4 (66.7) |

| Mean Age (SD) | 33.4 (6.4) | 33.2 (7.8) | 44.3 (11.9) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Latino/Hispanic | 9 (75.0) | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Non-Latino/Non-Hispanic | 3 (25.0) | 5 (62.5) | 6 (100.0) |

| Race | |||

| White/Caucasian | 8 (66.7) | 3 (37.5) | 6 (100.0) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| African American/Black | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian American | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 3 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Primary Discipline | |||

| Marriage Family Therapy | 6 (50.0) | ||

| Psychology | 3 (25.0) | ||

| Social Work | 3 (25.0) | ||

| Primary Theoretical Orientation | |||

| Cognitive-Behavioral | 6 (50.0) | ||

| Family Systems | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Eclectic | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Integrative | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Interpersonal | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Behavioral | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Highest Degree Held | |||

| Bachelor’s | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Master’s | 10 (83.3) | 6 (100.0) | |

| Doctorate | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Licensure | |||

| Licensed | 10 (83.3) | ||

| Unlicensed | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Mean Years of Experience (SD) | 5.8 (4.0) | ||

| Prior Training in Evidence-Based Practices | |||

| Received prior training | 11 (91.7) | ||

| Did not receive prior training | 1 (8.3) | ||

PACT pilot study caregiver participants

Caregivers in the current study were the subgroup of caregivers who participated in the PACT plus standard care condition of the parent study. Eligible caregivers were recruited from participating therapists’ caseloads. Of the 40 caregivers with whom therapists shared study information, 88% (n=35) agreed to be contacted by research staff. Caregivers were eligible if they: a) were the child’s legal guardian, b) were English-speaking, c) were at least 18 years old, d) had a child client between 4–13 years old, and e) the child client had caregiver-identified disruptive behavior problems, (e.g., aggression, noncompliance, delinquency) as a presenting problem for treatment, and f) had four or fewer sessions with the participating therapist. Twenty caregivers consented to participate in the study and were assigned to their child’s therapist’s condition (n=11 for PACT condition; n=9 for standard care condition). Two caregivers in the PACT plus standard care condition did not complete the follow-up interview and one caregiver completed the interview but declined to be audio recorded. The remaining eight caregivers comprised the caregiver sample for this study.

See Table 1 for caregiver participant demographic information. Child clients were all male, on average 7.8 years old (SD=2.8; range: 5.2–12.4), and all children had disruptive behavior problems as a presenting problem. The sample is generally representative of publicly funded clients served in this region in terms of child gender, ethnicity, and diagnosis (Zima et al., 2005).

PACT pilot study program manager participants

Program managers from the five participating clinics were invited to complete semi-structured interviews subsequent to pilot study completion at their site. All program managers contacted agreed to participate in the study; one clinic had two different program managers over the course of the study and both asked to be interviewed. The program manager inclusion criterion was that he/she served in a role as a program/agency manager or administrative leader during the PACT training process. See Table 1 for program manager participant demographic information.

Procedures

Procedures relevant to this study are described here. Additional information regarding PACT implementation can be found in the randomized controlled pilot study (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2016). At the end of four months, all PACT therapist and caregiver participants and program managers participated in a one-time, semi-structured individual interview. Interviews were conducted on the phone or in person and lasted an average of 46 minutes (therapist), 29 minutes (caregiver), and 32 minutes (program manager). Interviews were conducted by two interviewers, neither of whom was involved in PACT therapist training. Therapists and caregivers also completed survey questions online and via phone/in person, respectively, following the interview regarding their perceptions of PACT. One therapist did not complete the survey questions and is not represented in the quantitative analyses. Program managers responded to survey questions at the end of their interview.

Measures

Semi-structured interviews

The therapist interview questions were divided into four sections: 1) perceptions of the caregiver’s participation in treatment; 2) experience using each PACT tool (e.g., acceptability, appropriateness), including recommended changes to improve PACT; 3) any adaptations made while using PACT and barriers and facilitators to implementing PACT; 4) their future use of PACT. The caregiver interview questions were divided into three sections: 1) their participation in treatment; 2) their perspectives on each PACT tool, including recommended changes to improve PACT; and 3) the future utility of PACT. The program manager interview questions were organized into four sections: 1) information about the respondent’s role and questions regarding caregiver participation policies in their organization; 2) direct experience with PACT (e.g., supervising therapists, viewing the materials); 3) observations of acceptability and appropriateness of PACT for therapists in their clinic who utilized it; 4) future use of PACT in their clinic.

Surveys

Each participant completed a survey regarding their experiences with PACT to assess acceptability, appropriateness, and/or feasibility. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale with higher scores reflecting more positive perceptions. Caregivers and therapists completed 18-item (e.g., “Overall, would you recommend the use of PACT to a friend whose child is starting therapy?” and “Overall, how pleased are you with PACT?”) and 35-item (e.g., “I would recommend the toolkit to a colleague.” and “Participation in PACT training helps therapists develops skills in engaging parents.”) feedback surveys, respectively. Program managers answered three items (e.g., “Overall, would you recommend that other clinics use PACT?”). All surveys were designed for the current study.

Data Analysis

The qualitative data were analyzed using a coding, consensus, and comparison methodology (Willms et al., 1990), following an iterative approach based on grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). All interviews were transcribed and all transcripts were initially read by the first and second authors to identify general themes.

For therapist interview transcripts, the first and second authors developed a set of initial codes based on the Proctor et al. (2011) implementation outcome framework, initial review of the transcripts, and a separate coding system developed by the third author. The first and second authors then independently coded three randomly selected transcripts to develop an initial coding manual. Once the draft coding manual was complete, the first and second authors created two gold standard transcripts by coding two randomly selected transcripts and discussing discrepancies, ultimately finalizing a working draft of the coding manual. A third coder was then trained in the coding system using the two gold standard transcripts (this coder averaged above 80% reliability across those two gold standard transcripts) and then the remaining ten transcripts (including the three originally used in coding development) were double coded by the second author and third coder. Regular meetings were held between the two active coders and the first author (also the principal investigator) to reach consensus about discrepancies and to add clarification to codes and/or codes that emerged from the transcripts. After consensus was reached among coders, interview transcripts were entered, coded, and analyzed in QSR-NVivo 10.0, a program used frequently in qualitative research (Tappe, 2002).

For caregiver interview transcripts, three interviews were randomly selected and examined independently by the first two authors to develop an initial coding system. The first two authors then independently coded the remaining five interviews and met to achieve consensus in codes and add any emergent codes. For program manager interview transcripts, the first two authors conducted an initial read of the full set of transcripts to generate general themes and met to achieve consensus and extract themes for analysis. All resulting themes from the caregiver and program manager interviews were reviewed by the third author for clarity and consistency with exemplar quotes.

Results

Themes regarding therapist, caregiver, and program manager perceptions of PACT that emerged from analysis and integration of the qualitative data and corresponding quantitative data (when available) are presented below in three general categories with exemplar quotes: 1) implementation outcomes of PACT, 2) barriers and facilitators of implementing PACT, and 3) perceived effectiveness of PACT.

PACT Implementation Outcomes

Both the quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews with the three stakeholder groups (therapists, caregivers, and program managers) focused on several implementation outcomes of PACT (Proctor et al., 2011), namely acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility.

Acceptability

Overall satisfaction was assessed quantitatively across all three stakeholders. In addition, separate themes related to the tools and the toolkit training emerged from the interviews and were also assessed in the surveys.

Stakeholders satisfied overall with PACT

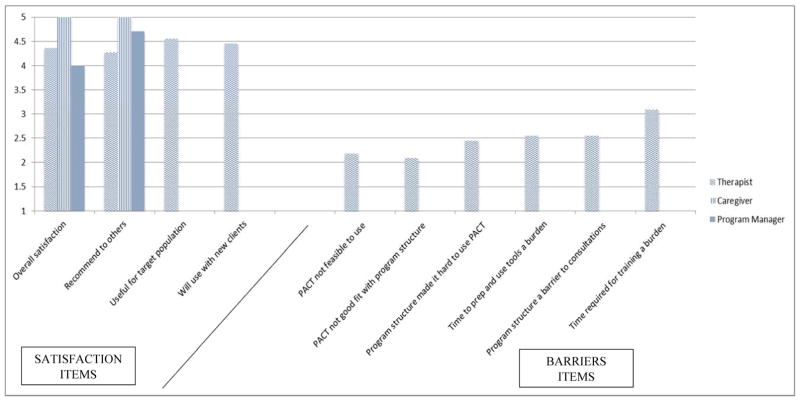

Survey data (see Figure 1) from all three stakeholders indicated high scores on several indicators of overall satisfaction (i.e., overall satisfaction, recommend to others, useful for the target population, will use with new clients). Specifically, mean ratings on these items fell in the “Agree to Strongly Agree” range. In addition, caregivers were asked about their satisfaction with each tool and their average ratings were very positive. A total of 63% of caregivers were very satisfied with the DVD (M=4.67, SD=.50; possible range 1–5), 100% were very satisfied with the Workbook (M=5.00; possible range 1–5), 100% were very satisfied with the Action Sheet (M=5.00; range 1–5), and 80% were very satisfied with the Messages (M=4.78, SD=.44; possible range 1–5).

Figure 1.

Stakeholder responses to survey satisfaction and barrier questions.

NOTE: Higher scores reflect greater perceived satisfaction or barriers. This figure does not present all the quantitative survey items included in this study. Some items are discussed specifically in the text.

PACT tools consistently perceived as useful

During the interviews, both therapists and caregivers described the individual tools as highly useful (see Table 2). Therapists described almost universally positive perceptions of the ACEs, DVD, workbook, and Action Sheet. Some variability was identified among therapists and caregivers regarding the PACT messages. Several therapists had positive comments while other therapists had more neutral comments about the utility of the messages. Caregivers were highly enthusiastic about all of the tools, including the messages (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Exemplar quotes.

| Therapist | Caregiver | Program Manager | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation Outcomes | |||

| Acceptability | |||

| Usefulness: Tools | “[The workbook] actually got her [the parent] to be engaged and maybe think about things differently. Our treatment isn’t just focused on the parent so it was helpful in having something kind of already there instead of having to come up with it on our own.” | “I loved [PACT Messages] ‘cause of its words of encouragement... feeling a little doubtful and then to get a message saying you’re doing a good job as a parent… I loved that.” | -- |

| Usefulness: Training | “I think the most useful was kind of getting to talk at the consultations about the goals we had developed. It’s kind of like we also were doing kind of what the parents were supposed to be doing.” | “It didn’t maximize the time… to effectively help us.” | “ …[PACT training] was not quite as user friendly as some of the other studies we’ve had in the clinic.” |

| Appropriateness | |||

| Fit | “I think that these are basic concepts that hopefully all of us are trained in… I think the way that they’re presented [in PACT] is a nice reminder, especially with the focus on parent participation…” “…it was nice to have a structure from the beginning where both of us had agreed that she was going to be involved…” |

“…so many times by the time you’re seeking therapy, you’re at the point where you’re just out of ideas. You don’t know what to do anymore... it [PACT Action Sheet] gives you some- it’s almost like giving you hope like ‘I’m prepared I can do this.’” | “…[PACT] helps us introduce the importance of parent participation and expectations and why it is important for [caregivers] to participate.” |

| Feasibility | “[PACT] had an ideal structure, but I really enjoy the flexibility because that was a big thing for my family where there’s a lot of things going on...” | “…everything was very simple. Very easy to use and understand.” | -- |

| Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation | |||

| Barriers | |||

| Time | “Like all the things, watching the vignette, maybe reviewing what needs to be done, making copies, charging the camera… take time.” | -- | “…I think she tried not to schedule a client after her PACT client because… it was difficult ending right on time.” |

| Technology | See text for summary of responses | -- | -- |

| Facilitators | |||

| Reminders | “I think the [training tip] reminders were helpful because I just have a lot going on… and so it was just helpful to be reminded…” | ||

| EBP Training | “…I took part in [an effectiveness trial of an evidence-based practice for children with disruptive behaviors and autism spectrum disorder], where we kind of would develop similar action plans with families.” | ||

| Leader Support | “… [clinic leaders] were also supportive about the participation… there was a week when [PACT trainer] named me the star of PACT because I had recruited the family and my boss got an email about that and she read it off in the staff meeting. So that kind of helps.” | “…I think just giving her the schedule flexibility, knowing that we would problem solve like the webinars, and things like that…I think was supportive to her.” | |

| Perceived Effectiveness of PACT | |||

| Therapist Changes | |||

| Caregiver Collaboration | “In my personal work I’ve been more directive than - more the expert ‘okay do this, do this.’ I think PACT is kind of like a covert way to do it by using the ‘we’ language and the suggestions and throwing my ideas in there but not imposing them; more just –, seeing what they think, you know. I really like the style. I think it has helped me to soften my style.” | “…and [my child’s therapist] was always [saying] ‘thank you for being a really, really, really excellent parent…’ [my child’s therapist] will see me come straight from work and [say]… ‘I thank you very much because you’re always here.’” | |

| Structuring Sessions | “…with the [PACT] Action Sheet… I have to follow-up on the things that were agreed upon the previous week. So that’s how it becomes like a really important tool.” | “…bringing to the tables like issues that I thought were important, like focusing on those from the [PACT] Action Sheet…[my child’s therapist] would say, ‘Did you guys do it? Did you not? Did it work?’” | |

| Caregiver Changes | |||

| Participation in Sessions | “He actually raised some very interesting concerns. He very much liked the Action Sheet, and had a lot of really good questions.” | “…with the [PACT] Action Sheet we came up with suggestions and routines and how to deal with the behavior when he [would] have his tantrums...” | |

| Participation Between Sessions |

“…She [caregiver] went above and beyond….in terms of giving the DVD to other people, really learning the skills.” “…she [caregiver] was more verbal with the school teacher and the day care providers for the client to make sure that on a daily basis she would be checking in with them to find out if there were any issues that were coming up as far as the child’s behavior.” |

“…we do have other adults who are involved in his life and everything so it was nice to be able to take it home and other people could see like ‘Oh this is what we‘re going to be working on.’… I’d be like ‘Oh yeah what did my sheet say? Yeah this is what we’re going to do.’” | |

| Mechanisms of Perceived Effectiveness | |||

| Caregiver Motivation | “I think [the DVD] was a good motivator for parents to get involved, instead of me as the clinician trying to convince them of that.” | “Well it, in the DVD it showed how they were there to help and no question or answer was wrong. So it kind of made you a little more confident in being there and participating…” | |

| Caregiver Reminders | “…the parent takes home the Action Sheet, so they’re reminded of the things that were important…” | “…The Action Sheet really… tells me what I’m supposed to do. I can follow that.’” | |

| Accountability | Therapist accountability: “…sometimes it seems like we’re going nowhere because [the families] bring a crisis and… [the Action Sheet] really gives direction and consistency.” Caregiver accountability: “…the family I think was in a way held accountable, because they have it in writing as well. So I think it made it a little bit easier for them to follow through.” |

||

| Normalizing Experiences | “…I would feel frustrated about the things that I was doing or I felt like am I the only one that’s dealing with this? So, looking at the DVD and listening to the other parents that was on the DVD, it really helped me a lot…” | ||

Variable perceptions of the usefulness of PACT therapist training

Interview responses demonstrated an overall positive perception of the training, with some variability in perceptions of the ongoing consultation webinars (see Table 2). Some therapists reported that the consultation webinars were helpful in learning to use the tools in their practice. Other therapists were less enthusiastic about the consultations. In addition, one program manager noted that PACT had less developed resources and training compared to well-developed EBP trainings in which that manager had been involved.

Therapists reported generally positive perceptions of the PACT training on their surveys. For example, 36% of therapists strongly agreed with the statement “I am satisfied with the PACT training package.” while an additional 55% agreed (M=4.27; SD=.65; possible range 1–5). For the item “Participation in PACT training helps therapists develop skills in engaging caregivers.” 55% strongly agreed with the statement while an additional 36% agreed (M=4.45; SD=.69; possible range 1–5). However, there was variability in therapist perceptions of individual training components. For the in-person training, 45% strongly agreed with their utility while the remaining 55% agreed (M=4.45; SD=.52; possible range 1–5). For the individual consultations, 45% strongly agreed with its utility and an additional 36% agreed, with the remaining 18% neutral (M=4.27; SD=.79; possible range 1–5). For the training manual, 27% strongly agreed with the utility while the remaining 73% agreed (M=4.27; SD=.47; possible range 1–5). The ongoing consultation webinars yielded the lowest average ratings; 55% strongly agreed with its utility and an additional 18% agreed, but 27% disagreed (M=4.0; SD=1.3; possible range 1–5).

Appropriateness

The degree to which PACT fit with therapist, caregiver, and program manager values and treatment goals emerged as a theme in the interviews and was also assessed in the therapist survey.

Strong fit with stakeholder values and goals for treatment

As demonstrated in Table 2, themes from the interviews demonstrated a strong fit with all stakeholders’ values and goals for treatment. For example, therapists reported that PACT served as a reminder to focus on caregiver engagement, which is valued but difficult to attend to consistently. In addition, therapists and program managers noted that caregiver participation is an important clinic and practice value and that PACT helps communicate the expectation of caregiver participation in services to families. Caregivers also indicated that PACT provides them with valuable tools to help their child’s treatment be successful.

On the therapist survey, average ratings for the statement, “The toolkit is compatible with the mission and values of my program” fell in the “Strongly Agree” range (M=4.18; SD=.75; possible range 1–5), with 50% of therapists indicating they strongly agreed with the statement and an additional 31% of therapists indicating they agreed.

Feasibility

The feasibility of using the toolkit in everyday practice was identified as a theme in the therapist and caregiver interviews and also assessed in the therapist survey.

PACT considered flexible and user-friendly with some variability in overall feasibility

As indicated in Table 2, therapists and caregivers described PACT as flexible and easy to use. Some variability in the perceived feasibility was seen in the therapist survey responses. Average ratings for the statement, “It is feasible to deliver the toolkit in my program.” fell in the “Agree” range (M=3.82; SD=1.08; possible range 1–5), with 27% of therapists indicating they strongly agreed with the statement and an additional 46% of therapists indicating they agreed. An additional 9.1% were neutral about the statement and 18.2% disagreed.

PACT Implementation Barriers and Facilitators

Both the interviews and surveys with the three stakeholder groups assessed perceived barriers and facilitators of PACT implementation in community settings.

Barriers to PACT implementation

The two primary barriers identified were time and technology.

Time as a barrier

One consistent barrier reported during the therapist and program manager interviews was lack of time for training support activities (sending in videos and written toolkit materials for review), preparing for sessions, and incorporating tools into existing sessions (see Table 2).

As indicated in Figure 1, therapists were asked about some specific barriers in their feedback survey. The greatest barrier they perceived was time required for training (“The time required to participate in PACT training activities was a significant burden”; 36% disagreed with the statement, 27% were neutral, 27% agreed, and 9% strongly agreed; M=3.09; SD=1.0; possible range 1–5). Some therapists also agreed with the statement “The time required to prepare for sessions was a significant burden.” with 18% strongly agreeing and 36% agreeing; M=2.64; SD=.92; possible range 1–5. A small number of therapists also agreed that “The time required to use the PACT Participation Tools was a significant burden (in sessions).” (18% agreed; M=2.45; SD=1.0; possible range 1–5). Please note, the two previous items were combined in Figure 1.

Technology as a barrier

Therapists discussed the use of technology required for PACT training as an implementation barrier. For example, uploading video recordings was slow due to clinics’ broadband access and requirements for the webinar interface made participating in consultations challenging for some therapists. This theme emerged from the interviews; no survey items were available to complement these qualitative data.

Facilitators to PACT implementation

The three primary facilitators identified were the reminders built into the toolkit to implement it, previous training in EBPs, and program leader support.

Reminders as a facilitator

As seen in Table 2, therapists spoke about the usefulness of concrete reminders to use the PACT tools, such as a reminder card created in the initial training and the weekly training tips. This theme emerged from the interviews; no survey items were available to complement the qualitative data.

Previous EBP training as a facilitator

Therapists discussed in the interviews how they utilized their experiences with common tools introduced in other EBP trainings (e.g., focus on caregiver skills, use of written materials, homework; see Table 2). This theme emerged from the interviews; no survey items were available to complement the qualitative data.

Program leader recognition and support as a facilitator

As shown in Table 2, when leadership support was present, therapists perceived this as a facilitator. Some program managers also acknowledged the importance of supporting staff in utilizing PACT (see Table 2). The majority of therapists reported receiving actual program leader recognition and support on their surveys. A total of 18% of therapists strongly agreed with the statement “My clinical supervisor or program leader encouraged me to participate in PACT.” while an additional 55% agreed (M=3.91; SD=.70; possible range 1–5).

PACT Perceived Effectiveness

Several themes across the quantitative and qualitative data emerged related to therapist and caregiver perceptions of PACT’s effectiveness to change therapists’ practices as well as caregiver participation in treatment. Themes also emerged regarding possible mechanisms of PACT that may explain how PACT may be effective.

Changes in therapists’ practices

Two themes relevant to changes in therapist practices were identified.

Increased focus on caregiver collaboration and empowerment

Therapists and caregivers both identified increases in therapists’ collaboration with and empowerment of caregivers while utilizing PACT in their interviews (see Table 2). This theme emerged from the interviews; no survey items were available to complement these qualitative data.

Increased session structure

Both therapists and caregivers identified increased session structure as a therapist practice change while using PACT (see Table 2). In addition, 36% of therapists strongly agreed with the statement “The toolkit helps therapy sessions stay on track.” while an additional 36% of therapist agreed (M=4.00; SD=1.00; possible range 1–5).

Changes in caregiver behaviors

Both therapists and caregivers identified changes in caregiver behaviors as a result of PACT.

Increased caregiver participation

Therapists and caregivers both highlighted increases in caregiver participation, both in and between sessions, in their interviews (see Table 2). In addition, 55% of therapists strongly agreed with the statement “The toolkit helps to engage parents/caregivers in their children’s treatment.” while the remaining 45% of therapists agreed (M=4.55; SD=.52; possible range 1–5).

Mechanisms of PACT perceived effectiveness

Several themes emerged out of the therapist and caregiver interviews relevant to mechanisms that may explain how PACT may be effective. No complementary quantitative data were available to examine alongside the themes described below.

PACT increased caregiver motivation to participate

Both therapists and caregivers shared that they believed PACT motivated caregivers to participate (see Table 2).

PACT reminded caregivers to follow-through at home

Therapists and caregivers both shared that PACT served as a helpful reminder to caregivers to follow-through at home with plans decided upon during sessions (see Table 2).

PACT provides accountability

Therapists highlighted how PACT, in particular the Action Sheet, provided accountability to both the therapist and the caregiver to remain on track with treatment goals and homework plans (see Table 2).

PACT normalizes caregivers’ experiences

Caregivers highlighted how PACT, in particular the DVD, normalized their experience of bringing their child for treatment and participating in treatment (see Table 2).

Discussion

The current study utilized mixed methods to examine community-based stakeholders’ (therapists, caregivers, and program managers) perspectives on the implementation and effectiveness outcomes of PACT, a toolkit to increase caregiver participation in services. This study expands the PACT randomized pilot study results (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2016), which found promising positive impacts on therapist attitudes and practices, caregiver participation behaviors, and caregiver perceived effectiveness of treatment, all of which are important service quality indicators (e.g., Garland et al., 2010; Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015; Hoagwood et al., 2012).

Perceptions of Implementation Outcomes

All stakeholders perceived PACT as an acceptable toolkit to implement in their settings given the consistently positive satisfaction ratings on the surveys. Acceptability is necessary for successful implementation of innovations (Proctor et al., 2011). Stakeholders viewed the tools overall as useful in promoting caregiver participation in treatment, with the most variability seen in the messages, in particular for therapists. The messages were the only tool that therapists did not receive any feedback about (the other tools they used directly with the caregiver), suggesting the importance of feedback loops back to the therapist about the impact of tools or intervention strategies they deploy.

In terms of PACT training, therapists reported variability in the usefulness of some training components, in particular the ongoing consultation webinars. Overall these findings are consistent with previous mixed methods research on therapists’ preferences for training in EBPs, in which respondents indicated a strong preference for training support, interactive training experiences, and topics that are both relevant and appealing (Herschell, Reed, Person Mecca, & Kolko, 2014). These results suggest that revising the consultations may be important in future implementation efforts. In addition, the study design may have been a barrier to optimal consultation implementation because not all consultation attendees were able to recruit a family and thus implement PACT; deployment of PACT in future implementation efforts should allow for all participating therapists to have eligible cases to implement the toolkit with at the onset of training. It was also notable that some therapists and program managers compared PACT training to more well-established, resource-rich EBPs that they had received training in. This finding suggests that community-based implementation of any structured practice change should take into account previous experiences stakeholders may have had with implementing practice changes such as EBPs.

Across all three stakeholder groups, the qualitative interviews highlighted the perceived appropriateness of PACT for community settings and these findings were complemented by the extant quantitative data. In particular, PACT seems to fit with each stakeholder’s values, which is an important factor for uptake in community settings (Proctor et al., 2011). For example, therapists perceived PACT as helping them focus on valued strategies to engage caregivers that may already be in their repertoire but are not a focus of their practice. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating that community-based therapists highly value focusing on the family rather than the child alone (Baumann, Kolko, Collins, & Herschell, 2006).

Regarding feasibility, both therapists and program managers reported that PACT was feasible to use in their community settings, although the quantitative results were not universally positive. Feasibility challenges are likely linked to the barriers to implementation that therapists and program managers identified, which are discussed in the next section.

PACT Implementation Barriers and Facilitators

In terms of barriers, the primary challenge therapists and program managers identified to implementing PACT was time available to devote to implementation. These findings are highly consistent with qualitative studies of therapist perceptions of implementing structured practice changes (e.g., Chung, Mikesell, & Miklowitz, 2014; Drahota, Stadnick, & Brookman-Frazee, 2014) and engagement strategies (Staudt et al., 2011). It is also notable that technology was a barrier to implementation (e.g., challenges with webinar technology; malfunctioning DVD players). Some of these challenges are related to the limited scope of funds available for this pilot study; others are due to the variability in resources available at the community settings the study took place in (e.g., IT support for computer issues related to the webinar software). As the role of technology as well as the sophistication of the technology itself increases in mental health treatment and services interventions, this may be less of a barrier for community settings.

It is important to note that despite these barriers, therapists implemented PACT as intended and with promising positive results on therapist attitudes and practices, caregiver participation, and to a limited extent caregiver perceived treatment effectiveness (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2016). As Figure 1 demonstrates, the challenges identified were not perceived as major barriers to using PACT (average scores ranged from 2.09–3.09 on a 1–5 scale with higher scores reflecting greater perceived challenge).

Facilitators of PACT implementation included the training components that served as reminders to utilize the materials, previous EBP training, and program leader recognition and support. These findings are consistent with prior training literature indicating that ongoing coaching and consultation enhances therapist skills and adherence (Edmunds, Beidas, & Kendall, 2013; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Marsenich, 2014). Findings are also consistent with recommendations for leaders to promote a strategic climate for EBP implementation, such as rewarding and recognizing delivery of a new practice (Aarons, Ehrhart, Farahnak, & Sklar, 2014). Taken together, these themes highlight the importance of integrating therapist training strategies with organization/leadership strategies to support EBP implementation, and support conceptual models of implementation highlighting the importance of factors at multiple levels (organization, therapists, intervention) (e.g., Aarons, Hurlburt, & Horwitz, 2011). It is interesting to note that no themes emerged regarding organizational/structural barriers such as billing or supervisor/supervision characteristics, in particular given the public funding context in which the pilot study took place and the high number of trainee participants. A lack of such themes may be related in part to the interview guide, the participants themselves, and/or the small sample sizes.

PACT Perceived Effectiveness

Both therapists and caregivers reported that PACT supported desired therapist practice changes, namely increased focus on caregiver collaboration and empowerment as well as increased session structure. The perceived increased focus on collaborating with and empowering caregivers is consistent with the demonstrated effects of PACT training on therapists’ actual practices (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2016). These results are particularly salient given previous research documenting a desire for increased caregiver collaboration and participation from both therapists and caregivers (Baker-Ericzén et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2014). The finding that PACT helped therapists more effectively structure sessions is consistent with therapists’ general perceptions of EBPs as helping them plan more effectively for sessions (Baumann et al., 2006). This increased efficiency is highly important as many therapists are under significant pressure for high levels of productivity at the same time as increased documentation requirements for reimbursement.

Therapists and caregivers also identified increased caregiver participation as a result of PACT. These findings are also consistent with some evidence that PACT increases observed caregiver participation (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2016). Increases in caregiver participation are a particularly important outcome given the encouraging links between participation and treatment outcomes (e.g., Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015), and suggest the promise of PACT as an effective toolkit to increases in caregiver participation and subsequently positive child and family outcomes.

In addition to the positive outcomes of PACT reported by stakeholders, therapists and caregivers identified several mechanisms of PACT’s perceived effectiveness, including that PACT increased caregivers’ motivation to participate, reminded caregivers to follow-through at home, provided accountability for both therapists and caregivers to focus on caregiver participation across sessions, and normalized the importance of caregivers’ participation. The motivation and social norm mechanisms identified are consistent with the determinants of behavior change identified by the UTB framework utilized in the toolkit’s development (Jaccard et al., 2002; Olin et al., 2010). Given the promising potential effectiveness of the toolkit demonstrated here and in Haine-Schlagel et al. (2016), these targets may be useful areas for future formal and informal efforts to increase caregiver participation in community mental health services.

Limitations

Some caution should be taken when interpreting study results given some limitations. First, the pilot study design resulted in small sample sizes, which limit the ability to obtain a wider range of perspectives about PACT. Despite this limitation, perspectives were obtained from three stakeholder groups, which strengthen the depth of information gathered. Further, the samples of therapists and caregivers were highly racially/ethnically diverse, which strengthens the generalizability of the results. Second, therapists in this sample were primarily unlicensed. More experienced, licensed therapists may have different perspectives on utilizing PACT in community-based settings than unlicensed therapists, as well as increased knowledge and skills that may facilitate or hinder implementation of PACT. Relatedly, the caregiver sample did not include any caregivers of female child clients, which limits generalizability to that portion of the population that utilizes community-based mental health services. However, many therapists in community-based mental health settings are often trainees and more boys than girls are typically served for disruptive behavior problems in community settings in this region (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2009; Zima et al., 2005); thus, the pilot study sample overall represents the community-based mental health service context. Third, it is important to note that PACT was delivered within clinic-based services. It is not known how PACT generalizes to other service settings such as school- or home-based services, or how PACT could be applied in telehealth or rural contexts. Fourth, this study did not address the appropriateness of PACT in relationship to reimbursement, which is an important consideration when moving the toolkit to scale. Lastly, it is notable that two of the 12 therapists did not implement the full toolkit protocol, which reflects the nature of both service delivery and conducting research in community-based settings. These therapists had two of the three briefest interviews, and review of their transcripts indicated that their comments focused primarily on the ACEs and the training components.

Clinical Application

Multiple stakeholder perspectives are important in understanding the barriers and facilitators of implementation, as well as implementation and effectiveness outcomes, of structured interventions implemented in community-based settings such as PACT. Stakeholder perspectives can guide both toolkit and provider training development and adaptations to fit community settings. In particular, themes related to barriers (e.g., technology) can provide direction for proactive attention and planning in future or similar efforts. Similarly, themes related to implementation facilitators such as program leader support and previous EBP training also provide guidance for future implementation of innovative practices. Further, themes regarding the fit of PACT suggest that designing a toolkit that takes into account and aligns with organizations’, therapists’, and caregivers’ values may be more likely to be adopted than treatment innovations that do not integrate and address stakeholder values. In addition, the themes related to PACT’s mechanisms of change provide insight into targets for future efforts to promote caregiver participation in community-based mental health services.

Conclusion

Results indicate that a toolkit designed with input from community-based providers and families to promote caregiver participation in treatment is perceived by multiple stakeholders as acceptable, appropriate, feasible, and effective to use in community settings. PACT appears to show promise as a toolkit to supplement standard child psychotherapy where the goal is often to engage families but barriers exist to reaching that goal.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23MH080149 (PI: Haine-Schlagel). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to acknowledge Jonathan Martinez, Ph.D., Cristina Bustos, Ph.D., Amy Drahota, Ph.D., Ann Garland, Ph.D., Cortney Janicki, and Emily Ewing for their contributions to this project as well as the participating clinics, therapists, and families. The authors also are grateful to Nicole Stadnick, Ph.D., MPH for reviewing an earlier version of this manuscript. Ms. Mechammil is currently a doctoral student at Utah State University in the Department of Psychology. No conflicts of interest exist.

References

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, Sklar M. The role of leadership in creating a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation and sustainment in systems and organizations. Frontiers in Public Health Services and Systems Research. 2014;3(4) doi: 10.13023/FPHSSR.0304.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Polo A, Gao S, Santana L, Rothstein D, Jiminez A, … Normand S. Evaluation of a patient activation and empowerment intervention in mental health care. Medical Care. 2008;46(3):247–256. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318158af52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JD, Linnan LA, Emmons KM. Fidelity and its relationship to implementation effectiveness, adaptation, and dissemination. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzén MJ, Jenkins MM, Haine-Schlagel R. Therapist, parent, and youth perspectives of treatment barriers to family-focused community outpatient mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22(6):854–868. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9644-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann BL, Kolko DJ, Collins K, Herschell AD. Understanding practitioners’ characteristics and perspectives prior to the dissemination of an evidence-based intervention. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:771–787. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Lee BR, Daleiden EL, Lindsey M, Brandt NE, Chorpita BF. The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(1):30–43. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.814543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Drahota A, Stadnick N, Palinkas LA. Therapist perspectives on community mental health services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012;39:365–373. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0355-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Garland AF, Taylor R, Zoffness R. Therapists’ attitudes towards psychotherapeutic strategies in community-based psychotherapy with children with disruptive behavior problems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0195-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta JJ, Lefever JB, Bigelow K, Borkowski J, Warren SF. Randomized trial of a cellular phone-enhanced home visitation parenting intervention. Pediatrics. 2013;132(Supplement 2):S167–S173. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1021Q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung B, Mikesell L, Miklowitz D. Flexibility and structure may enhance implementation of family-focused therapy in community mental health settings. Community Mental Health Journal. 2014;50:787–791. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9733-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes DE, Mulvaney-Day N, Fortuna L, Reinfeld S, Alegría M. Patient-provider communication: Understanding the role of patient activation for Latinos in mental health treatment. Health Education and Behavior. 2009;36:138–154. doi: 10.1177/1090198108314618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David-Ferdon C, Kaslow NJ. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):62–104. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day L, Reznikoff M. Preparation of children and parents for treatment at a children’s psychiatric clinic through videotaped modeling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1980;48:303–304. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.48.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell KA, Ogles BM. The effects of parent participation on child psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(2):151–162. doi: 10.1080/15374410903532585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drahota A, Stadnick N, Brookman-Frazee L. Therapist perspectives on training in a package of evidence-based practice strategies for children with autism spectrum disorders served in community mental health clinics. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Health Services Research. 2014;41(1):114–125. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0441-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds JM, Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Dissemination and implementation of evidence based practices: Training and consultation as implementation strategies. Clinical Psychology: Science And Practice. 2013;20(2):152–165. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Owens J, Bunford N. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(4):527–551. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.850700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn LM. Family perspectives on evidence-based practice. Child and Adolescent Clinics of North America. 2005;14(2):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, MacPherson HA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent bipolar spectrum disorders. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(3):339–355. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Brookman-Frazee L, Hurlburt M, Arnold E, Zoffness R, Haine-Schlagel R, Ganger W. Mental health care for children with disruptive behavior problems: A view inside therapists’ offices. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(8):788–795. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Baker-Ericzén M, Trask E, Fawley-King K. Improving community-based mental health care for children: Translatin knowledge into action. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Health Services Research. 2013;40(1):6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hawley KM, Brookman-Frazee L, Hurlburt MS. Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(5):505–514. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Wood PA, Aarons GA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:409–418. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Kruse M, Aarons GA. Clinicians and outcome measurement: What’s the use? Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2003;30:393–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02287427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn C, Franklin C, Nock MK. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(1):1–29. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S … Research Network on Youth Mental Health. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: Implications for research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. In: Zanna MP, Zanna MP, editors. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 38. San Diego, CA, US: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006. pp. 69–119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews is enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Bustos C. Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit (PACT): Therapist manual. San Diego State University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Fettes DL, Baker-Ericzén M, Garland AF. Therapist focus on parent involvement in community-based youth psychotherapy. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2012;21(4):646–656. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9517-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Martinez J, Roesch S, Bustos C, Janicki C. Randomized trial of the Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit for child mental health treatment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1183497. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Walsh N. Parent participation engagement in youth and family mental health treatment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2015;18(1):133–150. doi: 10.1007/s10567-015-0182-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Reed AJ, Person Mecca L, Kolko DJ. Community-based clinicians’ preferences for training in evidence-based practices: A mixed-method study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2014;45(3):188–199. doi: 10.1037/a0036488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Kiser L, Ringheisen H, Schoenwald SK. Evidence-basd practice in chlid and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(9):1179–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Cavaleri MA, Olin SS, Burns BJ, Slaton E, Gruttadaro D, Hughes R. Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13:1–45. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Jensen PS, Acri MC, Olin SS, Lewandowski RE, Herman RJ. Outcome domains in child mental health research since 1996: Have they changed and why does it matter? Journal Of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1241–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Henderson CE, Ozechowski TJ, Robbins MS. Evidence base on outpatient behavioral treatments for adolescent substance use: Updates and recommendations 2007–2013. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(5):695–720. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.915550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Stroul B, Friedman R, Mrazek P, Friesen B, Pires S, Mayberg S. Transforming mental health care for children and their families. American Psychologist. 2005;60(6):615–627. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM. Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2010;19(5):629–645. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dodge T, Dittus P. Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: A conceptual framework. In: Feldman SS, Rosenthal DA, Feldman SS, Rosenthal DA, editors. Talking sexuality: Parent-adolescent communication. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 9–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, Handelsman JB, Fields S, Bickman L. Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: The evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah JWT, Johnston C. Parent social cognitions: Considerations in the acceptability of and engagement in behavioral parent training. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11:218–236. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, McCadam K, Gonzales JJ. Addressing the barriers to mental health services for inner city children and their caretakers. Community Mental Health Journal. 1996;32(4):353–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02249453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Nudelman R, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Evaluating a social work engagement approach to involving inner-city children and their families in mental health care. Research on Social Work Practice. 1996;6(4):462–472. doi: 10.1177/104973159600600404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Stoewe J, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their caretakers. Health and Social Work. 1998;23(1):9–15. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KW, Woodruff K, Moon C, Finney C. Using text messaging to improve attendance and completion in a parent training program. Journal Of Child And Family Studies. 2015;24(10):3107–3116. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0115-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Ferriter C. Parent management of attendance and adherence in child and adolescent therapy: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for increasing participation in Parent Management Training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(5):872–879. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin S, Hoagwood KE, Rodriguez J, Ramos B, Burton G, Penn M, et al. The application of behavior change theory to family-based services: Improving parent empowerment in children’s mental health. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(4):462–470. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA. Qualitative and mixed methods in mental health services and implementation research. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(6):851–861. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.910791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity and therapeutic change: Issues and research recommendations. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12(4):365–383. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpi045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polo AJ, Alegría M, Sirkin JT. Increasing the Engagement of Latinos in Services Through Community-Derived Programs: The Right Question Project-Mental Health. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;43:208–216. doi: 10.1037/a0027730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons GA, Bunger A, … Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Southam-Gerow M, O’Connor MK, Allin RB. An analysis of stakeholder views on children’s mental health services. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(6):862–876. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.873982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J, Olin SS, Hoagwood KE, Shen S, Burton G, Radigan M, Jensen PS. The development and evaluation of a parent empowerment program for family peer advocates. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2011;20(4):397–405. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9405-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow AJ, Letourneau EJ, Liao JG. Transportability of multisystemic therapy: Evidence for multilevel influences. Mental Health Services Research. 2003;5(4):223–239. doi: 10.1023/A:1026229102151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self-Brown S, Whitaker DJ. Parent-focused child maltreatment prevention: Improving assessment, intervention, and dissemination with technology. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:400–416. doi: 10.1177/1077559508320059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Saiz CC. Clinical, empirical, and developmental perspectives on the therapeutic relationship in child psychotherapy. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4(4):713–728. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Pina AA, Viswesvaran C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):105–130. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt M. Treatment engagement with caregivers of at-risk children: Gaps in research and conceptualization. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16(2):183–196. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9077-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]