Abstract

Risk is an important parameter to describe the occurrence of health outcomes over time. However, many outcomes of interest in healthcare settings, such as disease incidence, treatment initiation, and cause-specific mortality, may be precluded from occurring by other events, often referred to as competing events. Here, we review straightforward approaches to estimate risk in the presence of competing events. We illustrate the application of these methods using timely examples in pharmacoepidemiologic research and compare results to those obtained using analytic simplifications commonly used to handle competing events. These examples demonstrate how the analytic methods used to account for competing events affect the interpretation of results from pharmacoepidemiologic studies.

Keywords: Pharmacoepidemiology, Epidemiologic Methods, Survival Analysis, Bias (Epidemiology)

Introduction

Health sciences research, including pharmacoepidemiology, seeks to inform healthcare decisions and policy development. Descriptions of the occurrence of health outcomes can help researchers and public health practitioners understand the burden of conditions, identify high-risk groups, and plan for resource allocation. Comparisons of the occurrence of health outcomes under 2 or more policies, treatment plans, or interventions can inform decision making in public health and medicine. “Risk” is a foundational parameter to describe the occurrence of health outcomes in epidemiologic studies (1). In this paper, we discuss considerations in estimating risks of important outcomes in pharmacoepidemiology, such as disease incidence, medication uptake, and cause-specific mortality.

All outcomes (events of interest) other than all-cause mortality may require special consideration in analyses because they may be precluded from occurring by competing events. For example, in a study of medication uptake, participants who die before starting the medication will never be able to start the medication. In this case, death is a competing event which precludes the occurrence of the event of interest, medication initiation. In studies of cause-specific mortality, death due to causes other than the cause of interest are competing events.

Competing events are not the same as censoring events and should be treated differently in analyses. While a competing event precludes the outcome from occurring, a censoring event merely prevents us from observing the outcome. Common reasons for censoring include loss to follow-up or administrative end of follow-up before the outcome occurs. Though the distinction between competing events and censoring events has been noted in many fields of clinical research [for example, (2–9)], competing events continue to bring up methodological challenges in the estimation of risk in many settings (10).

Here, we first summarize a modern definition of risk and then outline approaches to estimate risk in settings with competing events. Next, we discuss extensions to estimate counterfactual risks, or risks that would have occurred, under various treatment plans. Throughout the paper, we illustrate concepts using examples derived from recent pharmacoepidemiologic studies.

Parameters and estimators

Risk is a function describing the cumulative probability of an event of interest occurring over time since a given origin in a specific population. Risk can be reported at any specified time since the origin. The origin is the time at which an individual becomes at risk for the event under study; that is, where they have any probability of experiencing the event and having their event observed by investigators. The appropriate origin depends on both the event under study and the study question. Multiple origins may be appropriate for a given event (11), and we discuss considerations in choosing the optimal origin in the Discussion.

First, note that risk at time t is a probability, meaning that it is bounded by 0 (no subjects experience the outcome by time t) and 1 (all subjects experience the outcome by time t). Risk can be interpreted as a population average probability or as the proportion of subjects expected to experience the outcome by time t (1). Second, note that risk is a function of time since the origin, and as such, risks should always be reported with the time period for which they are calculated.

When no competing events are possible, such as when studying all-cause mortality, or when the follow-up time is so short that no competing events occurred, we can define risk as the cumulative distribution function for the time between the origin and the event of interest, F(t), where

and Ti is the time from the origin to the event of interest for subject i. In this setting, F(t) can be estimated as the complement of any consistent estimator of the survival function, such as the Kaplan-Meier estimator.

Because competing events are nearly ubiquitous in pharmacoepidemiology, we discuss a generalization of the risk function allowing for multiple event types in the remainder of this paper. We will denote the risk function for event type j as F(t, j), where

Ti is the time from the origin to the event of interest or the competing event and Ji is the event type for subject i. This risk function is sometimes called the cumulative incidence function (12,13). The risk F(t, j) may be estimated using the Aalen-Johansen estimator (14)

where dkj is the number of events of type j occurring at time k, nk is the number of subjects at risk of the event at time k, dkj/nk is the cause-specific hazard for the event of interest at time k, and Ŝ(k − 1) an estimate of the overall survival function at the previous time point. Ŝ(k − 1) can be estimated using any consistent estimator for the survival function, such as the Kaplan-Meier estimator S(t) = Πk≤t{1 − dk/nk} where dk is the total number of events of any type at time k (15).

Several ad hoc simplifications exist to estimate quantities related to risk in the presence of competing events. These simplifications include censoring the competing events and using composite endpoints. Using these simplifications changes the interpretation of the results in many settings. In the following sections, we discuss each of these simplifications and compare risk estimated using the Aalen-Johansen estimator to risk estimated by censoring the competing events (example 1) and using a composite endpoint (example 2).

Simplification 1: Censor competing events

Sometimes epidemiologists simply censor records at the time subjects experience a competing event. Rather than acknowledging that a competing event precludes the event of interest, censoring a competing event is equivalent to assuming that the event of interest occurs at some time point after the competing event. The measure that results from censoring competing events is the conditional risk, or the risk that would be observed if all competing events in the cohort were prevented from occurring without altering the hazard of the event of interest (16–18). However, it is difficult to imagine the intervention that would completely eliminate competing events, much less the intervention that would completely eliminate competing events without also changing the risk of the event of interest. The assumptions necessary for interpreting conditional risks limit the utility of such estimates for measuring public health impact.

Estimates of conditional risk, obtained by censoring competing events, are always greater than or equal to estimates of risk obtained using the Aalen-Johansen estimator. This is because each censored observation up-weights events observed after the censoring time (19). To see why, consider that an analysis that censors the competing events scales the cause-specific hazard by the cause-specific survival function S(k − 1, j) rather than the overall survival function S(k − 1). The resulting estimator is

Note that the cause-specific survival function S(t, j) will always be greater than or equal to the overall survival function S(t) if there are any competing events. In the setting where competing events are censored, the cause-specific hazard will be scaled by a larger value, resulting in inflated estimates of risk. The degree of inflation will be proportional to the incidence of the competing event. In settings where competing events are rare, S(t, j) ≈ S(t) and censoring the competing events will have little impact on the estimated risk for event type j. However, when competing events are common or the event of interest is rare, censoring the competing events can dramatically distort estimates of risk.

Simplification 2: Use a composite endpoint

A second common simplification in analyses with competing risks is to estimate the risk of a composite endpoint. That is, the outcome is defined as the first of several possible endpoints (e.g., AIDS or death prior to an AIDS diagnosis). Specifying a composite endpoint is useful in many settings, particularly when all of the event types are of interest or when the number of occurrences of a single event type is small (20–22). If all competing event types are included in the composite endpoint, the risk function collapses to F(t). However, combining multiple event types may obscure important relationships between exposures and the event type of interest, particularly if the event type of interest is rare compared to all other event types. In addition, combining a beneficial outcome (e.g., cancer remission or hospital discharge) with a negative outcome like death may render a composite endpoint difficult to interpret. Approaches to weight the types of competing events in a composite endpoint or to assign a utility function to the types of competing events may offer a way forward in these settings (1,23).

PART 1. RISK UNDER NO INTERVENTION ON TREATMENT PLAN

We refer to risk estimated under no intervention on the conditions, treatments, exposures, or policies that occurred during the study as risk under the “natural course”. Estimating risk under the natural course is an important tool to understand specific target populations (24). For example, describing the risk of a given disease, uptake of a new drug, or the risk of death after contracting a disease (or starting a drug) in a given population requires estimation of risk under the natural course. Risks at specific points in time from the origin (e.g., at 5 years after treatment initiation) can be compared between subsets of study participants using risk ratios or risk differences.

To estimate the risk under the natural course, we must assume that 1) the event time is measured without error; 2) the event type is measured without error; and 3) that subjects under observation are exchangeable with subjects not under observation at time t (25–27). Methods to relax each of these assumptions are explored in the Discussion.

Example: Estimating the risk of cancer-related mortality by comorbidity status under the “natural course”

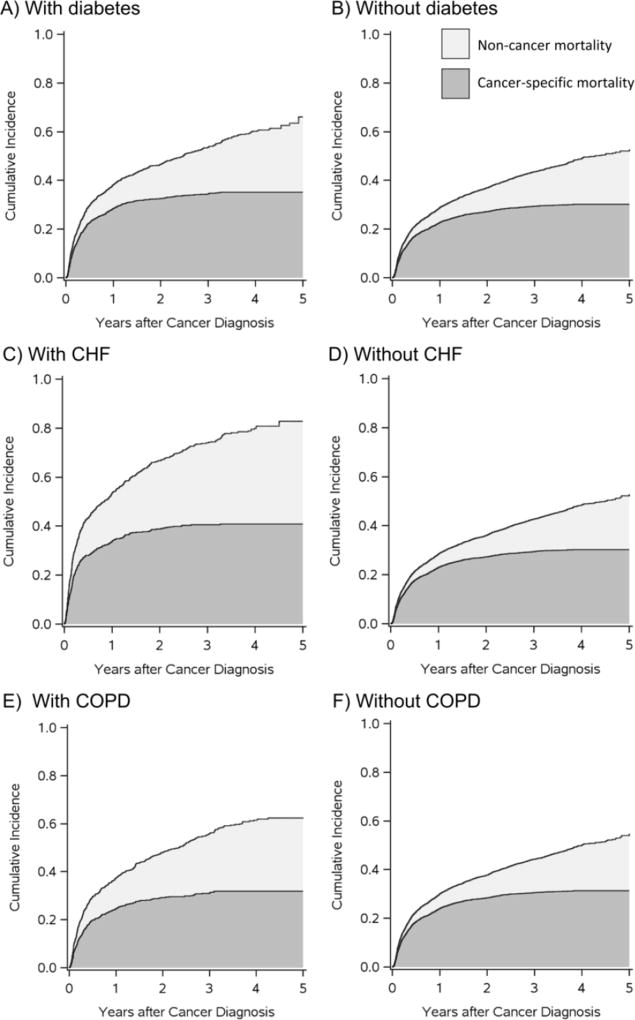

In the example below, we estimate 5-year cancer-related mortality risks using a large claims database linked with cancer registry data. First, we use the Aalen-Johansen estimator, F̂(t, j), to account for competing events in cancer-related risk estimates and illustrate graphical approaches to display risks of competing event types. Then, we compare risk estimated using F̂(t, j) with conditional risk estimated by censoring the competing events F̂cs(t, j).

We compare cancer-related mortality risk between patients with and without each of 3 common comorbidities at the time of their cancer diagnosis: diabetes, congestive heart failure (CHF), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The analysis included patients aged ≥65 years diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) from 2007–2009 who resided in any of 18 Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry areas at diagnosis and had linked US Medicare health insurance claims. All patients were required to have 12 months of continuous enrollment in Medicare before NHL diagnosis so that prevalent diabetes, CHF, or COPD could be identified using validated ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes in claims data (28). We followed patients from NHL diagnosis until death from any cause or administrative censoring at 5 years or on December 31, 2012. Deaths were ascertained from US death certificate data collected and maintained by the National Center for Health Statistics. The National Cancer Institute’s algorithm (29) was used to identify deaths due to cancer (j=1), and deaths not meeting the cancer classification were considered non-cancer deaths (j=2).

Because older patients have a high probability of dying from non-cancer conditions before they die of cancer, censoring patients when they experience a competing non-cancer death will overestimate cancer-related mortality risk. We estimated 5-year risks and conditional risks of cancer-related and non-cancer mortality using the Aalen-Johansen estimator F̂(t, j) and the estimator in which competing events were censored F̂cs(t, j), respectively. We contrasted risks and conditional risks between groups with and without diabetes, CHF, and COPD using risk ratios. Confidence intervals were estimated as the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of point estimates obtained from 1000 bootstrap samples of the data (30). SAS code to estimate the risk functions is provided in Appendix 1.

Among the 5192 NHL patients included in the analysis, 1284 (25%) had prevalent diabetes, 620 (12%) had CHF, and 810 (16%) had COPD. Over the study period, there were 2514 deaths, for a 5-year all-cause mortality risk of 56%. Of these deaths, 1600 were cancer-related deaths and 914 were related to other causes. The 5-year risks of cancer and non-cancer related mortality were higher for patients with each comorbidity than without each comorbidity (Table 1). Figure 1 presents a graphical depiction of F̂(t, 1) and F̂(t, 2) showing the relationship between the risk functions for the two competing event types (31).

Table 1.

5-year cancer-related and non-cancer mortality risks and risk ratios for 5192 patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin between 2007 and 2009 in a US Medicare population

| Risk: Accounting for competing events | Conditional risk: Censoring competing events | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Deaths | Cancer-related 5-year mortality |

Non-cancer 5-year mortality |

Cancer-related 5-year mortality |

Non-cancer 5-year mortality |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Group | Total | Cancer | Non- cancer |

Risk % |

RR (95% CI) | Risk % |

RR (95% CI) | Risk % |

RR (95% CI) | Risk % |

RR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 5192 | 1600 | 914 | 31.4 | --- | 24.6 | --- | 33.4 | --- | 33.7 | --- | |

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||

| No | 3908 | 1154 | 634 | 30.2 | 1 | 22.4 | 1 | 31.9 | 1 | 30.3 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1284 | 446 | 280 | 35.2 | 1.16 (1.10,1.24) | 30.9 | 1.38 (1.26, 1.50) | 38.0 | 1.19 (1.09,1.31) | 44.9 | 1.47 (1.18,1.80) | |

| CHF | ||||||||||||

| No | 4572 | 1353 | 699 | 30.3 | 1 | 22.6 | 1 | 31.8 | 1 | 31.0 | 1 | |

| Yes | 620 | 247 | 215 | 40.9 | 1.35 (1.21,1.50) | 43.0 | 1.90 (1.69,2.10) | 48.5 | 1.52 (1.36,1.69) | 65.6 | 2.19 (1.75,2.63) | |

| COPD | ||||||||||||

| No | 4382 | 1341 | 693 | 31.3 | 1 | 23.4 | 1 | 33.0 | 1 | 32.2 | 1 | |

| Yes | 810 | 259 | 221 | 31.9 | 1.02 (0.92,1.12) | 31.1 | 1.33 (1.18,1.50) | 35.8 | 1.08 (0.95,1.21) | 42.1 | 1.31 (1.09,1.54) | |

Figure 1.

Cancer-related (dark gray) and non-cancer (light gray) mortality risks a (stacked) after diagnosis with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) among Medicare patients aged over age 65 who have or do not have diabetes (A and B), CHF (C and D), and COPD (E and F) at NHL diagnosis.

a Cancer-related and non-cancer mortality risks are estimated using the Aalen Johansen estimator. In this figure, cancer-related mortality risks and non-cancer mortality risks are stacked, such that the top line of the two stacked curves represents all-cause mortality risk. Stacked plots like these allow the depiction of risk for all event types in a single plot.

Conditional risks, estimated by F̂cs(t, j), were greater than risks estimated by F̂(t, j) for all groups (Table 1). For example, estimates of conditional risk F̂cs(5,1) and F̂cs(5,2) in the overall study sample (not stratifying on comorbidity) were 33% and 34%, respectively, while estimates of risk F̂(5,1) and F̂(5,2), which were 31% and 25%, respectively. Furthermore, because the risk of non-cancer mortality was higher among patients with each of the three comorbidities under study, conditional cancer-related mortality risks estimated using F̂sc(5,1) were more inflated for patients with each comorbidity than for patients without, and thus conditional risk ratios comparing F̂cs(5,1) between persons with versus without comorbidities were higher than risk ratios calculated by comparing F̂(5,1) between groups. The inflation in the risk ratio was greatest for CHF, which had the highest non-cancer mortality. The risk ratio comparing 5-year cancer-related mortality for patients with CHF versus those without CHF when non-cancer deaths were censored was 1.52 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.36, 1.69], while the risk ratio was 1.35 (95% CI: 1.21, 1.50) when competing events were taken into account using the Aalen-Johansen estimator.

PART 2. COUNTERFACTUAL RISK UNDER TREATMENT PLAN a

Sometimes, rather than compare outcomes between 2 groups of patients, we wish to compare the outcomes that would have occurred in the same group of patients under 2 or more treatment strategies. The risk that would have occurred under treatment plan a is known as the counterfactual risk under treatment plan a, and will be denoted Fa(t, j) = P(Ta ≤ t, Ja = j), where Ta is the time from the origin to the event and Ja is the event type under treatment plan a. The counterfactual risk is the proportion of subjects we would expect to experience event j by time t if all subjects were observed from origin to event and all subjects received treatment plan a. Counterfactual risks are particularly important for pharmacoepidemiology due to their role in comparative effectiveness studies (32–34).

Counterfactual risks can be estimated under the assumptions outlined to estimate risk under the natural course in part 1, plus the additional assumption that subjects receiving treatment plan a are exchangeable with subjects not receiving treatment plan a at time t. Exchangeability implies that the counterfactual risk, or the risk that would have occurred under treatment plan a, is the same for patients who actually received treatment plan a as for patients who received other treatment plans. We can relax the exchangeability assumption to be conditional on a vector of covariates Z using inverse probability of treatment weights (35–37), as will be demonstrated in the next example. Other methods are possible, including the parametric g-formula (38–40) and targeted maximum likelihood estimation (41). Relaxing the exchangeability assumption to be conditional on Z additionally requires the assumptions of positivity (42) (that is, that participants in all strata of Z have nonzero probability of being exposed to treatment plan a) and correct specification of parametric models.

Inverse probability weights are a particularly appealing tool to estimate counterfactual risks (36,43,44). As described by Cole et al. (45), the weighted Aalen-Johansen estimator takes the form

where is the weighted number of events of type j at time k, is the weighted number of subjects in the risk set at time k, and is the weighted number of all events at time h regardless of event type. The weights for each subject may take the form Wi = f{A}/f{A|Z}, where Z is a vector of covariates needed to satisfy the conditional exchangeability assumption and f{A} represents the conditional density function for A evaluated at the observed value. Other forms of the weights are possible when, for example, treatment plan is time-varying (37) or depends on subject-specific covariates (46). When competing events may occur, Z must include all covariates needed to satisfy the assumption of conditional exchangeability between the treatment plan and both the event of interest and the competing events (47). If censoring is informative, an additional set of weights, may be used to account for differences between participants lost to follow-up and participants remaining in the study. Existing work provides technical details on censoring weights (48), intuition behind when and why such weights are needed (25), and practical details on when and how to implement censoring weights (26). The final weight for each subject is the product of the treatment and censoring weights. For a practical example of exposure and censoring weights in a setting with competing events, see (45).

Example: Comparative risks of cardiovascular events under 2 antidiabetic drugs

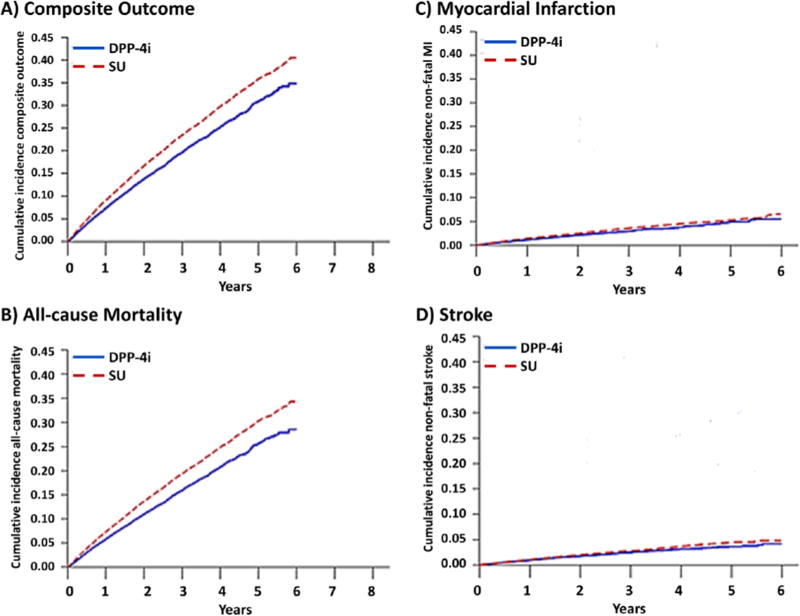

In the following section, we compare counterfactual risk of CVD events under 2 alternative treatment strategies. Full details are available in work by Gokhale (49). Briefly, this example compares risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke among Medicare enrollees under initiation of two second line antidiabetic drugs, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) and sulfonylureas (SU), between 2007 and 2013. In this example, death is a common competing event. As in example 1, censoring patients who die may lead to overestimation of individual risks of MI or stroke. Instead, here we compare the two treatments using risk differences for MI and stroke (estimated using the Aalen-Johansen estimator) with risk differences for a composite endpoint of MI, stroke, or death.

This study included Medicare enrollees over age 65 who initiated DPP-4i (n = 44,771) or SU (n = 119,436) and had not used either of these drugs during the 6 months before drug initiation. To increase the probability that patients were actually started on treatment (reduce potential for secondary non-adherence), patients were required to fill a second script of the same drug class in the 180 days after initiation. Patients were followed from the date of their second prescription to the earliest of MI, stroke, death, treatment changes (stopping, switching or augmenting), end of Medicare enrollment or end of the administrative follow-up in December 2013. We compared risk at multiple time points using risk differences. Confidence intervals were obtained from the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the point estimates from 1000 bootstrap resamples of the data (30).

This new-user active comparator design is analogous to a head-to-head randomized controlled clinical trial that answers the question of ‘which second-line treatment to initiate’ rather than ‘whether to initiate a second-line treatment or not’ (50). Using an active comparator design balances the treatment groups with respect to many baseline patient characteristics and minimizes confounding by indication and confounding by frailty or functional status (51,52). We minimized remaining differences in a set of measured covariates between exposure groups using inverse probability of treatment weights (36,43,44).

In this example, 4,720 composite events occurred among the DPP-4i initiators (725 MI, 593 stroke, and 3770 deaths) and 20,274 composite events occurred among SU initiators (2765 MI, 2209 stroke, and 17,046 deaths) over the follow-up period. Deaths accounted for approximately 80% of the events in both treatment groups indicating that a summary effect measure for the composite outcome would mainly represent the effect on death rather than the individual outcomes of MI or stroke. The risks under each treatment plan of the composite outcome and all-cause mortality indicate a protective effect of DPP-4i (Figure 2). However, risks of MI and stroke were similar under DPP-4i and SU when mortality was treated as a competing event and risk estimated with the Aalen-Johansen estimator. The adjusted risk difference for MI comparing DPP-4i versus SU ranged from −0.27% (95% CI: −0.46%, −0.06%) at 1 year to −0.78% (95% CI: −1.62%, 0.12%) at 5 years and the adjusted risk difference for stroke ranged from −0.11% (95% CI: −0.23%, 0.03%) to −0.81% (95% CI: −1.30%, −0.22%) at 1 and 5 years, respectively.

Figure 2.

Counterfactual risk functions for A) a composite endpoint (MI, stroke and all-cause mortality), B) all-cause mortality, C) myocardial infarction (MI), and D) stroke under initiation of dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) and sulfonylureas (SU) among US Medicare recipients, 2007–2013

Dashed line: sulfonylureas

Solid line: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor

Discussion

Here, we have summarized straightforward methods to estimate risk in settings with competing events. In addition, we have illustrated the application of these methods to estimate risk under the natural course and counterfactual risk using examples from pharmacoepidemiology. The examples have highlighted how competing events can inflate estimates of risk when they are inappropriately treated as censoring events and can mask or distort causal associations between treatments and outcomes when they are included as part of a composite event.

Assumptions are always required to estimate risk and counterfactual risk in scenarios with and without competing events. Methods exist to relax each of these assumptions and have been explored extensively in settings without competing events (35,53–56). The same methods can be applied to estimate risk in the presence of competing events. For example, in the sections above, we summarized methods to account for nonrandom treatment plan assignment (i.e., lack of exchangeability between treatment groups or confounding) and informative censoring using inverse probability weights. Appropriately relaxing assumptions in the presence of competing events may be slightly more complex than when competing events are not present; for example, the assumption of no unmeasured confounding in the presence of competing events must hold not only for the effect of the treatment plan on the event of interest, but also for the effect of the treatment plan on the competing event(s) (47). Extensions of the Aalen-Johansen estimator also exist to account for mismeasurement of event type (57) and event time (58).

Risk can only be interpreted when presented as a function of time since some clearly defined origin, such as time since medication initiation or time since first treatment indication. The chosen origin should be meaningful for whomever ultimately uses the information from the study (e.g., the clinician or policy maker). The elements of the best origin for a particular analysis have been described a debated enthusiastically in the general epidemiology and pharmacoepidemiology literature (52,59–61). Analyzing observational studies like hypothetical, pragmatic randomized trials can clarify decisions around the choice of origin (62). Once choice of origin has been set, we have highlighted that risk is a function of time and as such any reported risk (or risk difference or risk ratio) must be accompanied by the time since the origin for which it was calculated. In both examples, we have also presented the full risk function such that the reader can see how risk changes as a function of time; risk ratios and risk differences could likewise be presented as a function of time (45).

In both examples presented here, we compared risks between groups (example 1) and counterfactual risks (example 2) using risk ratios and risk differences, respectively. Alternatively, we could have compared groups or treatment plans using crude or adjusted hazard ratios from the subdistribution proportional hazards model described by Fine and Gray (63). Such regression models are beyond the scope of this paper, but are explained clearly for the epidemiologist in work by Lau et al (64) and Andersen et al (65). To illustrate how results from this approach compare with the risk ratios estimated in example 1, we have included subdistribution hazard ratios of cancer-related mortality for patients with and without each comorbidity in Appendix 2. We also compare the subdistribution hazard ratios to cause-specific hazard ratios estimated using cause-specific Cox proportional hazards models. Because comorbidities were associated with higher risk of non-cancer mortality, cause-specific hazard ratios, which censor competing events, were higher than subdistribution hazard ratios. However, the relationship between cause-specific hazard ratios and subdistribution hazard ratios is not always predictable. In settings where the effects of exposure on the event of interest and the competing event are in opposite directions, cause-specific hazard ratios and subdistribution hazard ratios may not be on the same side of the null (66,67).

Conclusions

Competing events are ubiquitous in pharmacoepidemiologic research. Popular simplified analytic solutions to handling competing events include censoring the competing events or using a composite endpoint that combines all possible event types. The method used to account for competing risks can alter the interpretation of study results and can dramatically affect absolute and relative risk estimates, particularly when competing events are not rare. We have highlighted issues that may arise when using these analytic simplifications, and illustrated the use of the Aalen-Johansen estimator obtain interpretable, policy-relevant estimates of risk in the presence of competing events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH U01 HL121812, U01 DA036935, R01 AI100654, and 5R25CA116339-07.

The project presented in Example #1 was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health through Grant Award Number 1UL1TR001111. The database infrastructure for example #1 was funded by the CER Strategic Initiative of UNC’s Clinical Translational Science Award (1 ULI RR025747) and the UNC School of Medicine. The authors thank Dr. Jennifer Lund, the PI for this project, for use of the data. The authors also acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute’s Applied Research Program, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Office of Research, Development, and Information, the Information Management Services, Inc., and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

The database infrastructure used for Example #2 was funded by the Pharmacoepidemiology Gillings Innovation Lab (PEGIL) for the Population-Based Evaluation of Drug Benefits and Harms in Older US Adults (GIL200811.0010), the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Epidemiology, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, the CER Strategic Initiative of UNC’s Clinical Translational Science Award (UL1TR001111), the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, UNC, and the UNC School of Medicine.)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Mugdha Gokhale is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline.

Laure Hester, Catherine Lesko and Jessie Edwards declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All studies referenced in this work by Edwards, Lesko, Gokhale, and Hester involving human subjects were performed after approval by the appropriate institutional review board. When required, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- 1**.Cole SR, Hudgens MG, Brookhart MA, Westreich D. Risk. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;181(4):246–250. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv001. ** Defines risk as a foundational parameter for epidemiologists. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verduijn M, Grootendorst DC, Dekker FW, Jager KJ, le Cessie S. The analysis of competing events like cause-specific mortality--beware of the Kaplan-Meier method. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011;26(1):56–61. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noordzij M, Leffondré K, van Stralen KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Jager KJ. When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013;28(11):2670–2677. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolbers M, Koller MT, Stel VS, Schaer B, Jager KJ, McMurray J, et al. Competing risks analyses: objectives and approaches. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35(42):2936–41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akolekar R, Syngelaki A, Poon L, Wright D, Nicolaides KH. Competing Risks Model in Early Screening for Preeclampsia by Biophysical and Biochemical Markers. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2013;33(1):8–15. doi: 10.1159/000341264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dignam JJ, Zhang Q, Kocherginsky M, Gelman R, Gelber R, Beyersmann J, et al. The use and interpretation of competing risks regression models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18(8):2301–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Andersen PK. The clinical course of cirrhosis: The importance of multistate models and competing risks analysis. Hepatology. 2015;62(1):292–302. doi: 10.1002/hep.27598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler AM, Olshan AF, Kshirsagar AV, Edwards JK, Nielsen ME, Wheeler SB, Brookhart MA. Cancer Incidence Among US Medicare ESRD Patients Receiving Hemodialysis, 1996–2009. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015;65(5):763–772. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesko CR, Edwards JK, Moore RD, Lau B. A longitudinal HIV care continuum: 10-year restricted mean time in each care continuum stage after enrollment in care, by history of injection drug use. Aids. 2016 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001183. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koller MT, Raatz H, Steyerberg EW, Wolbers M. Competing risks and the clinical community: irrelevance or ignorance? Stat. Med. 2012;31(11–12):1089–1097. doi: 10.1002/sim.4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farewell AVT, Cox DR. A Note on Multiple Time Scales in Life Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C. 1979;28(1):73–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray RJ. A Class of K-Sample Tests for Comparing the Cumulative Incidence of a Competing Risk. Ann. Stat. 1988;16(3):1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The statistical analysis of failure time data. J. Wiley; 2002. p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aalen OO, Johansen S. An Empirical Transition Matrix for Non-Homogeneous Markov Chains Based on Censored Observations. Scand. J. Stat. 1978;5(3):141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958;53(282):457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prentice RL, Kalbfleisch JD, Peterson aV, Flournoy N, Farewell VT, Breslow NE. The analysis of failure times in the presence of competing risks. Biometrics. 1978;34(4):541–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenland S. Causality theory for policy uses of epidemiological measures. Summary measures of population health: Concepts, ethics, and applications. 2002:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. 2. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer MS, Zhang X, Platt RW. Analyzing risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;179(3):361–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernán MA, Schisterman EF, Hernández-Díaz S. Invited commentary: composite outcomes as an attempt to escape from selection bias and related paradoxes. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;179(3):368–370. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer MS, Zhang X, Platt RW, Kramer, et al. respond to “Composite outcomes and paradoxes”. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;179(3):371–372. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernán MA, Schisterman EF, Hernández-Díaz S. Invited commentary: composite outcomes as an attempt to escape from selection bias and related paradoxes. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;179(3):368–370. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westreich D, Edwards JK, Rogawski ET, Hudgens MG, Stuart EA, Cole SR. Causal Impact: Epidemiological Approaches for a Public Health of Consequence. Am. J. Public Health. 2016;106(6):1011–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):615–625. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26*.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Lau B, Napravnik S, Eron JJ. Selection Bias Due to Loss to Follow Up in Cohort Studies. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):91–97. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000409. * Describes considerations when estimating absolute risks in the presence of selection bias. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuart EA, Cole SR, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ. The use of propensity scores to assess the generalizability of results from randomized trials. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A. Stat. Soc. 2011;174(2):369–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2010.00673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howlader N, Ries LAG, Mariotto AB, Reichman ME, Ruhl J, Cronin KA. Improved estimates of cancer-specific survival rates from population-based data. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010;102(20):1584–1598. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat. Med. 2007;26(11):2389–2430. doi: 10.1002/sim.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Using Big Data to Emulate a Target Trial When a Randomized Trial Is Not Available: Table 1. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016;183(8):758–764. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young JG, Cain LE, Robins JM, O’Reilly EJ, Hernán MA. Comparative effectiveness of dynamic treatment regimes: an application of the parametric g-formula. Stat. Biosci. 2011;3(1):119–143. doi: 10.1007/s12561-011-9040-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oakes JM. Effect identification in comparative effectiveness research. EGEMS (Washington, DC) 2013;1(1):1004. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Adjusted survival curves with inverse probability weights. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2004;75(1):45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):656–664. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robins J. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with a sustained exposure period: application to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Math. Model. 1986;7(9–12):1393–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keil A, Edwards JK, Richardson DB, Naimi AI, Cole SR. The Parametric g-Formula for Time-to-event Data Intuition and a Worked Example. Epidemiology. 2014;25(6):889–897. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards JK, McGrath LJ, Buckley JP, Schubauer-Berigan MK, Cole SR, Richardson DB. Occupational radon exposure and lung cancer mortality: Estimating intervention effects using the parametric g-formula. Epidemiology. 2014;25(6):829–834. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stitelman OM, De Gruttola V, van der Laan MJ. A General Implementation of TMLE for Longitudinal Data Applied to Causal Inference in Survival Analysis. Int. J. Biostat. 2012;8(1) doi: 10.1515/1557-4679.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westreich D, Cole SR. Invited commentary: positivity in practice. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;171(6):674–677. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie J, Liu C. Adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test with inverse probability of treatment weighting for survival data. Stat. Med. 2005;24(20):3089–3110. doi: 10.1002/sim.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westreich D, Cole SR, Tien PC, Chmiel JS, Kingsley L, Funk MJ, Anastos K, Jacobson LP. Time scale and adjusted survival curves for marginal structural cox models. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;171(6):691–700. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45**.Cole SR, Lau B, Eron JJ, Brookhart MA, Kitahata MM, Martin JN, Mathews WC, Mugavero MJ. Estimation of the Standardized Risk Difference and Ratio in a Competing Risks Framework: Application to Injection Drug Use and Progression to AIDS After Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;181(4):238–245. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu122. ** Applied example illustrating approaches to estimate counterfactual risk in an HIV cohort study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cain LE, Robins JM, Lanoy E, Logan R, Costagliola D, Hernán MA. When to Start Treatment? A Systematic Approach to the Comparison of Dynamic Regimes Using Observational Data. Int. J. Biostat. 2010;6(2) doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1212. Article 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47**.Lesko C, Lau B. Bias due to confounders for the exposure-competing risk relationship when estimating the cumulative incidence function or subdistribution relative hazard. Epidemiology. 2016 doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000565. in press. ** Provides guidance on avoiding confounding bias in studies of endpoints with competing events. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robins JM, Rotnitzky A. Recovery of information and adjustment for dependent censoring using surrogate markers. In: Jewell M, Dietz K, Farewell V, editors. AIDS Epidemiology - Methodological Issues. Boston, MA: Birkhäuser; 1992. pp. 297–331. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gokhale M. Spotlight Poster Presentation at the International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management (ICPE) Dublin: Ireland; 2016. Comparative Incidence of Cardiovascular Events in Older Adults Initiating DPP-4 Inhibitors versus Other Antidiabetic Drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray WA. Evaluating Medication Effects Outside of Clinical Trials: New-User Designs. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003;158(9):915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Lund JL, Richardson DB, Stürmer T. The active comparator, new user study design in pharmacoepidemiology: historical foundations and contemporary application. Curr. Epidemiol. reports. 2015;2(4):221–228. doi: 10.1007/s40471-015-0053-5. * Provides context for decisions regarding the origin and comparison group of interest, both of which are important when comparing risks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52*.Brookhart MA. Counterpoint: The Treatment Decision Design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;182(10):840–845. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv214. * Presents a generalization of the new user design, with important ramifications for the choice of origin in pharmacoepidemiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS clinical trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56(3):779–788. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toh S, Hernández-Díaz S, Logan R, Robins JM, Hernán MA. Estimating absolute risks in the presence of nonadherence: an application to a follow-up study with baseline randomization. Epidemiology. 2010;21(4):528–539. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181df1b69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edwards JK, Cole SR, Westreich D, Crane H, Eron JJ, Mathews WC, Moore R, Boswell SL, Lesko CR, Mugavero MJ. Multiple Imputation to Account for Measurement Error in Marginal Structural Models. Epidemiology. 2015;26(5):645–652. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cole SR, Jacobson LP, Tien PC, Kingsley L, Chmiel JS. Using marginal structural measurement-error models to estimate the long-term effect of antiretroviral therapy on incident aids or death. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;171(1):113–122. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57**.Bakoyannis G, Yiannoutsos CT. Impact of and Correction for Outcome Misclassification in Cumulative Incidence Estimation. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137454. ** Outlines methods to account for outcome misclassification when estimating risk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cook TD, Kosorok MR. Analysis of Time-to-Event Data With Incomplete Event Adjudication. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004;99(468):1140–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vandenbroucke J, Pearce N. Point: incident exposures, prevalent exposures, and causal inference: does limiting studies to persons who are followed from first exposure onward damage epidemiology? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;182(10):826–33. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hernán MA. Counterpoint: epidemiology to guide decision-making: moving away from practice-free research. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;182(10):834–839. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vandenbroucke J, Pearce N. Vandenbroucke and Pearce Respond to “Incident and Prevalent Exposures and Causal Inference”. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;182(10):846–847. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hernán MA, Alonso A, Logan R, Grodstein F, Michels KB, Willett WC, Manson JE, Robins JM. Observational studies analyzed like randomized experiments: an application to postmenopausal hormone therapy and coronary heart disease. Epidemiology. 2008;19(6):766–779. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181875e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fine JP, Gray R. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009;170(2):244–56. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Andersen PK, Geskus RB, De witte T, Putter H. Competing risks in epidemiology: Possibilities and pitfalls. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):861–870. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Allignol A, Schumacher M, Wanner C, Drechsler C, Beyersmann J, Scheike T, et al. Understanding competing risks: a simulation point of view. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011;11(86):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67*.Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopin M, Fine JP. A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;66(6):648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.017. * Outlines considerations on reporting results from studies with competing events. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.