Abstract

Context

Although behavioral therapy has been shown to improve post-operative recovery of continence, there have been no controlled trials of behavioral therapy for post-prostatectomy incontinence persisting more than 1 year.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of behavioral therapy for reducing persistent post-prostatectomy incontinence, and to determine whether the technologies of biofeedback and pelvic floor electrical stimulation enhance the effectiveness of behavioral therapy.

Design

Prospective, randomized, controlled trial conducted from 2003 to 2008, with 1-year follow-up after active treatment.

Setting

University and 2 Veterans Affairs continence clinics

Participants

Volunteer sample of 208 community-dwelling men; ages 51–84 years; 75% white, 24% African American; with incontinence persisting 1–17 years after radical prostatectomy.

Interventions

After stratification by type and frequency of incontinence, participants were randomized to 8 weeks of 1) Behavioral Therapy (pelvic floor muscle training and bladder control strategies), 2) Behavioral Therapy plus in-office, dual-channel EMG biofeedback and daily home pelvic floor electrical stimulation at 20 Hz, current up to 100 mÅ (Behavior Plus), or 3) Delayed-Treatment Control.

Main Outcome Measures

Percentage reduction in mean number of incontinence episodes after 8 weeks of treatment as documented in 7-day bladder diaries

Results

Mean incontinence episodes decreased from 28 to 13 per week (55% reduction; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 44%–66%) after Behavioral Therapy and 26 to 12 (51%; 95% CI=37%–65%) after Behavioral Plus. Both reductions were significantly greater than the reduction from 25 to 21 (24%; 95% CI=10%–39%) observed among controls (p’s=0.001), but not from each other (p=.69). Improvements were durable to 12 months in the active treatment groups, 50% (95% CI=39.8–61.1%; 13.5 episodes/week) reduction in Behavior and 59% (95% CI=45.0–73.1%; 9.1 episodes/week) in Behavior Plus, (p=.32).

Conclusions

Among patients with post-prostatectomy incontinence for at least 1 year, 8 weeks of behavioral therapy, compared with a delayed-treatment control, resulted in fewer incontinence episodes. The addition of biofeedback and pelvic floor electrical stimulation did not result in greater effectiveness.

Men in the U.S. have a 1 in 6 lifetime prevalence of prostate cancer.1 Although survival is excellent, urinary incontinence is a significant morbidity following radical prostatectomy,1–4 often the treatment of choice for localized prostate cancer. Patient surveys indicate that as many as 65% of men continue to experience incontinence up to 5 years after surgery.2 Loss of bladder control can be a physical, emotional, psychosocial, and economic burden for men who experience it.2,4

Post-prostatectomy incontinence has been attributed to intrinsic sphincter deficiency and/or detrusor dysfunction, leading to stress and/or urgency incontinence respectively.3 Surgical interventions for incontinence are quite effective,5–7 but usually reserved for moderate to severe incontinence, and many prostate cancer survivors are reluctant to undergo another surgery.

Several randomized trials have examined the effectiveness of perioperative pelvic floor muscle training and shown a significant reduction in duration and severity of incontinence in the early post-operative period.8–12 However, no previous trials have tested the effectiveness of behavioral therapy for incontinence persisting more than a year after prostatectomy. Biofeedback, which assists patients to properly contract pelvic floor muscles8 and pelvic floor electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerves, which produces a maximal pelvic floor contraction and improves urethral closure pressure as well as reducing detrusor overactivity12,13 are often used together in practice and are thought to enhance the effectiveness of behavioral therapy, but empirical evidence of a benefit is lacking.10,12

The objectives of this trial were to evaluate the effectiveness of behavioral therapy for reducing persistent post-prostatectomy incontinence and impact on quality of life, and to determine whether the technologies of biofeedback and electrical stimulation enhance its effectiveness.

METHODS

This study was a multi-site, randomized controlled trial of behavioral therapy (pelvic floor muscle exercises, bladder control techniques, and fluid management) with or without biofeedback and pelvic floor electrical stimulation, compared with a delayed-treatment control condition conducted between January 2003 and June 2009. The study was registered with Clinical Trials.gov and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the participating sites.

Participants

Community-dwelling men with incontinence persisting at least 1 year after radical prostatectomy were recruited through advertisements, prostate cancer support groups, and the investigators’ clinical practices. Written informed consent was provided by each participant. After telephone screening, an evaluation was conducted consisting of a history and physical, Mini-Mental State Exam,14 7-day bladder diary, urinalysis, hemoglobin A1c for participants with diabetes, simple uroflow, and post-void residual volume by ultrasound. Race was self-reported using categories provided by the investigators to describe the sample and was assessed because racial differences in incontinence have been reported.15

Men who were incontinent before their prostatectomy or men who resolved post-prostatectomy incontinence and then developed incontinence at a later time were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included <2 incontinence episodes/week, prostatectomy <1 year ago, current active prostate cancer treatment other than hormonal therapy, post-void residual urine volume >200mL, prior treatment in a structured behavioral therapy program, artificial urinary sphincter or suburethral sling, cardiac pacemaker, Mini-Mental State Exam14 score <24, inability to quantitate individual leakage episodes on bladder diary, and unstable medical conditions. Participants on an anticholinergic medication for incontinence were eligible after a 2-week wash-out period. Participants with fecal impaction, urinary tract infection, hematuria, or hemoglobin A1c >10 were eligible after appropriate treatment.

Stratification and Randomization

Participants were stratified by site (one university and two VA medical centers), and by incontinence type (stress, urgency, or mixed) and severity (<5, 5–10, or >10 episodes/week) to ensure equal distribution among treatment groups. For each site, for each of the 9 stratification cells, a random assignment schedule was generated by a computer program written by the biostatistician. To maintain allocation concealment, group assignments were placed in sealed envelopes and opened sequentially at the time of randomization.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was percent reduction in number of incontinence episodes at 8 weeks as measured with a 7-day bladder diary,16 scored by study staff blinded to group assignment. The AUA-7 Symptom Index17 was used to measure lower urinary tract symptoms and the IPSS Quality of Life Question to measure impact.18 Condition-specific quality of life was also measured with the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire19,20 and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC).21 General quality of life was measured with the SF-36.22 To assess participants' perceptions of treatment effects, we used the Global Perception of Improvement23 and the Patient Satisfaction Question.23 All instruments were completed at home, brought to the clinic, and scores tabulated and entered by research staff who were blinded to group assignment.

Interventions

Behavioral Therapy was implemented in 4 visits approximately 2 weeks apart by physician investigators or nurse practitioners. Visit 1 consisted of an explanation of continence-related anatomy and pelvic floor muscle exercises, followed by teaching using anal palpation. Participants were instructed in pelvic floor muscle contraction without breath holding or contraction of abdominal, thigh, or buttock muscles. Home exercises included 3 daily sessions (1 each lying, sitting, and standing) with 15 repetitions of a 2- to 10-second contraction followed by an equal period of relaxation depending on the participant’s demonstrated ability. The contraction/relaxation duration was advanced by one second each week to a maximum of 10–20 seconds. Participants were instructed to practice interruption or slowing of the urinary stream during voiding once daily for the first 2 weeks. Participants kept daily bladder diaries/exercise logs during the 8 weeks of treatment. A fluid management handout containing information on normal intake (6–8 eight-ounce glasses daily) and advice to avoid caffeine and distribute fluid consumption across the day was provided.

At Visit 2, diaries were reviewed and participants were taught bladder control strategies. The strategy for preventing stress incontinence was to contract pelvic floor muscles just before and during activities that caused leakage, such as coughing or lifting. The urge control strategy involved instructions to not rush to the toilet, but instead to stay still and contract the pelvic floor muscles repeatedly until urgency abated and then proceed to the bathroom at a normal pace.

In subsequent visits, diaries were reviewed and success or failure with bladder control strategies discussed in detail to improve results and adherence. If the diary did not document at least a 50% reduction in incontinence episodes at visit 3, pelvic floor muscle training was repeated.

Behavioral Therapy Plus Biofeedback and Electrical Stimulation (Behavior Plus) was conducted as described above with the addition of in-office, dual-channel biofeedback and daily home pelvic floor electrical stimulation. At Visit 1, the pelvic floor muscle exercises were taught using feedback from surface EMG electrodes placed over the rectus abdominis muscles and perianally or with an anal probe. The participant was coached to achieve a reliable and sustained contraction without contracting rectus abdominis muscles. Electrical stimulation training was conducted in-office at visit 1, using the home unit, an anal probe, and settings of 20 Hz, pulse width 1 msec, duty cycle of 5 seconds on and 15 seconds off, 15 minute sessions, and current up to 100mÅ as adjusted by the participant to achieve a palpable pelvic floor contraction. In addition to daily home electrical stimulation, participants were instructed to perform two daily sessions of pelvic floor muscle exercises to keep the frequency of exercise sessions similar between treatment groups. Biofeedback was repeated at visit 3 if incontinence frequency had not decreased by 50%.

Participants in the Delayed-Treatment Group (Control) kept daily bladder diaries, which were reviewed during their clinic visits every two weeks for 8 weeks to control for self-monitoring effects, as well as the attention of the practitioner and clinic staff. After 8 weeks, they were offered off-protocol treatment with their choice of behavioral therapy with or without biofeedback and/or electrical stimulation.

Treatment Durability

At 8 weeks, instructions for a maintenance program of daily pelvic floor exercises (fifteen 10-second paired contraction/relaxations), continued use of bladder control strategies and fluid management were provided in the two active treatment groups. These participants were seen at 6 and 12 months to assess treatment effect durability.

Power Calculation

Power was based on the primary outcome variable, mean percent reduction in incontinence episodes on diary, using a within-group standard deviation of 31% based on our previous work and assuming two-tailed tests. In addition to omnibus main effect tests, sufficient power was desired for conducting 3 possible pair-wise comparisons among the three groups, so the type I error rate (alpha) was set at .0125 (.05/3). With these specifications, using an intent-to-treat analysis, and predicting a 15% drop-out rate, the planned sample size of 204 enrolled participants would provide power greater than .80 to detect differences between any two groups of 18% or larger.

Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome analysis used an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach. Bladder diaries completed by participants prior to randomization and at 8 weeks were used to calculate percent reduction in the number of incontinence episodes for each participant. For each treatment group, the means of the individual percent reductions were then calculated. In 36 cases (17.3%) where participants failed to provide post-treatment data, a multiple imputation procedure with 8 imputations was utilized. Group differences were tested using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Pair-wise comparisons between the three groups were conducted only if the omnibus F-statistic from the overall analysis indicated that the null hypothesis should be rejected. Participants in the two treatment groups were followed at 6 and 12 months and additional percent reduction values were calculated for men who completed these visits. T-tests were conducted to determine if the groups statistically differed from each other. For secondary outcome measures, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used with the baseline observation serving as a covariate. Chi-square tests were used to compare the groups on categorical outcomes. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., 2008).

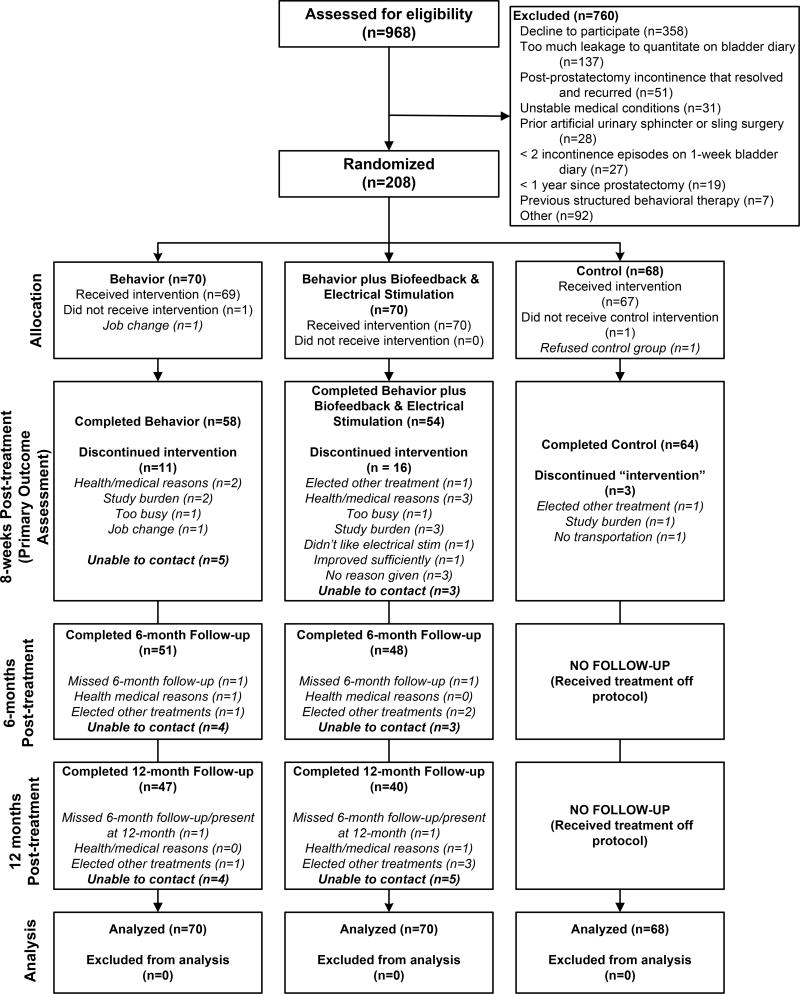

RESULTS

Of 968 men who were screened for eligibility, 208 were randomized, and of these, 176 (85%) completed 8 weeks of treatment. Of the 112 men completing active treatment, 87 (78%) were followed for 1 year. Reasons for ineligibility and attrition are shown in Figure 1. There were no group differences in attrition (p=.25) and no differences between completers and non-completers on the baseline variables. Characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. At baseline, there were no statistically significant differences among the 3 groups.

Figure 1.

Study Participants

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| N=208 total* | Behavior (n = 70) |

Behavior Plus (n = 70) |

Control (n = 68) |

P value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD***) | 66.3 (7.5) | 66.8 (7.0) | 66.9 (7.7) | 0.90 |

|

| ||||

| Race (self-reported), n (%) | ||||

| African American | 19 (27.1) | 15 (21.4) | 16 (23.5) | 0.72 |

| White | 51 (72.9) | 54 (77.1) | 50 (73.5) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (3.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Body Mass Index (n=197), mean (SD) | 30.0 (5.2) | 27.9 (4.1) | 29.0 (5.4) | 0.06 |

|

| ||||

| Years since radical prostatectomy n=205, mean (SD) | 5.1 (4.1) | 3.9 (3.2) | 5.1 (4.4) | 0.12 |

|

| ||||

| Type of Incontinence per diary, n (%) | ||||

| Urge | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Stress | 31 (44.3) | 33 (47.1) | 30 (44.1) | 0.95 |

| Mixed | 38 (54.3) | 35 (50.0) | 37 (54.4) | |

|

| ||||

| Incontinence Severity, episodes/wk on diary, mean (SD) | 28.1 (22.0) | 25.6 (26.0) | 24.8 (19.9) | 0.68 |

|

| ||||

| Prior Treatments, n (%) | ||||

| Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises | 25 (35.7) | 39 (55.7) | 32 (47.1) | .06 |

| Antimuscarinic Medications | 11 (15.7) | 14 (20.0) | 19 (27.9) | .20 |

| Alpha Blocker Medications | 2 (2.9) | 3 (4.3) | 2 (2.9) | .87 |

|

| ||||

| Unable to Contract Pelvic Floor Muscles during Initial Physical Exam | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | .36 |

|

| ||||

| EPIC‡ (n=206), mean (SD) | ||||

| Urinary Domain | 65.4 (12.9) | 69.0 (11.4) | 64.5 (11.7) | 0.07 |

| Incontinence Subscale | 40.4 (17.4) | 43.1 (17.2) | 39.1 (16.1) | 0.37 |

|

| ||||

| IIQ‡‡ (n=206), mean (SD) | ||||

| Physical Activity subscale | 26.7 (29.3) | 23.7 (24.9) | 23.4 (22.7) | 0.72 |

| Travel subscale | 24.1 (29.9) | 19.8 (22.6) | 21.8 (22.3) | 0.61 |

| Social Relationships subscale | 25.2 (27.9) | 20.2 (20.7) | 25.3 (21.5) | 0.35 |

| Emotional subscale | 27.9 (27.7) | 22.2 (22.2) | 26.9 (21.4) | 0.33 |

| Total Score | 104.0 (108.7) | 86.0 (79.2) | 97.4 (78.7) | 0.49 |

|

| ||||

| SF-36‡‡‡ (n=200), mean (SD) | ||||

| Physical Component Summary | 48.1 (8.4) | 49.4 (7.9) | 48.7 (7.7) | .61 |

| Mental Component Summary | 49.8 (11.4) | 52.4 (8.4) | 51.4 (10.3) | .31 |

|

| ||||

| AUA-7§ (n=205), mean (SD) | ||||

| Total Score | 10.7 (6.9) | 9.0 (4.7) | 11.0 (5.3) | 0.08 |

| Voiding Subscale | 4.2 (4.2) | 3.0 (2.7) | 4.0 (3.4) | 0.10 |

| Storage Subscale | 6.5 (3.5) | 6.0 (3.1) | 7.0 (3.3) | 0.18 |

|

| ||||

| IPSS QOL Question§§ (If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary problem the way it is now, how would you feel about that?) (n=205), n (%) | ||||

| Delighted | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pleased | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mostly satisfied | 4 (5.7) | 14 (20.0) | 6 (9.2) | 0.22 |

| Mixed | 21 (30.0) | 21 (30.0) | 22 (33.9) | |

| Mostly dissatisfied | 20 (28.6) | 16 (22.9) | 24 (36.9) | |

| Unhappy | 14 (20.0) | 13 (18.6) | 9 (13.9) | |

| Terrible | 8 (11.4) | 4 (5.7) | 4 (6.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Activity Restriction due to Incontinence, n (%) | ||||

| Not at all | 38 (54.3) | 50 (71.4) | 37 (54.4) | 0.16 |

| Some of the time | 22 (31.4) | 16 (22.9) | 27 (39.7) | |

| Most of the time | 8 (11.4) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (4.4) | |

| All of the time | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.5) | |

|

| ||||

| How disturbing is leakage of urine? n (%) | ||||

| Not at all | 1 (1.4) | 5 (7.1) | 2 (2.9) | 0.28 |

| Somewhat disturbing | 51 (72.9) | 54 (77.1) | 50 (73.5) | |

| Extremely disturbing | 18 (25.7) | 11 (15.7) | 16 (23.5) | |

If totals are less than 208 for each variable, the n is specified.

P-values are from ANOVA analyses which determine if there is an overall group difference on each variable.

SD = standard deviation

EPIC = Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (subscale scores range 0–100 with higher scores representing better health-related quality of life)

IIQ = Incontinence Impact Questionnaire, subscale scores range from 0 to 100, total score 0 to 400, with higher scores indicating greater impact

SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better functional health and well-being

AUA-7 = American Urological Association Symptom Index; total score ranges 0–35, storage subscale (frequency, urgency and nocturia) 0–15, and voiding subscale (reduced stream, hesitancy, and straining) 0–20, with higher scores indicating higher symptom frequency.

IPSS QOL = International Prostate Symptom Scale Quality of Life question

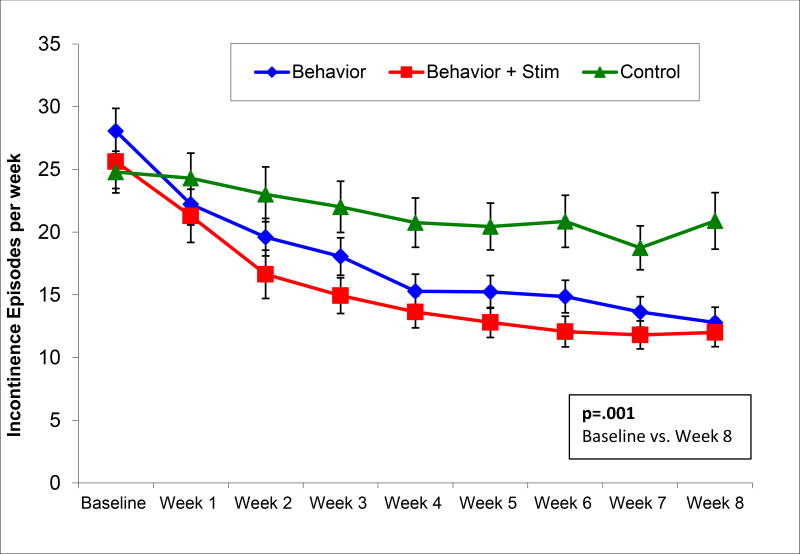

The multiple imputation ITT analysis demonstrated a significant difference in mean percent reduction of incontinence episodes/week among groups at the end of treatment, F(2,205)=7.02, p=.001 (Table 2; Figure 2). At 8 weeks, percent reduction was 55% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 44%–66%; 28 to 13 episodes/week) after Behavioral Therapy, significantly better than the mean 24% (95% CI=10%–39%; 25 to 20 episodes/week) reduction in Control, b=30.65 (95% CI=12.22–49.08), p=.001. The addition of biofeedback and electrical stimulation did not improve 8-week results over behavioral therapy alone, demonstrating a mean percent reduction of incontinence episodes/week of 51% (95% CI=37%–65%; 26 to 12 episodes/week) which was also significantly better than control, b=26.74, 95% CI=7.14–46.35, p=.01. There was no significant difference between the Behavioral Therapy and Behavior Plus groups, b = 3.91, 95% CI=−15.07–22.88, p=.69. These improvements were sustained for the 12 month follow-up period (Table 3), 50% (95%CI 40%–61%; 13.5 episodes/week) reduction in the Behavior group and 59% (95%CI 45%–73%; 9.1 episodes/week) in the Behavior Plus group. Complete continence, zero episodes on 7-day bladder diary at 8 weeks, was attained by 11 of 70 (15.7%) men in Behavioral Therapy, 12 of 70 (17.1%) in Behavior Plus, and 4 of 68 (5.9%) in Control, with a number needed to treat of 10 (95% CI=5.3–44.6).

Table 2.

Treatment Outcomes and Adherence at 8 Weeks

| Behavior | Behavior Plus | Control | P value* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Percent Improvement in Incontinence Episodes on Bladder Diary n=208, mean (95% CI), | 55% (44%–66%) | 51% (37%–65%) | 24% (10%–39%) | 0.001 |

| Mean episodes per week(95% CI) | 13 (12–14) | 12 (11–13) | 21 (19–23) | |

|

| ||||

| Change in EPIC‡ n= 172, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Urinary Domain | 11.5 (8.9–14.1) | 8.4 (6.0–10.9) | 2.6 (0.6–4.6) | <0.001 |

| Incontinence Subscale | 13.1 (9.1–17.1) | 12.3 (8.4–16.2) | 2.9 (−0.2–5.9) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Change in IIQ‡‡ n=170, median (range) | ||||

| Physical Activity subscale | −5.6 (−77.8–27.8) | −5.6 (−83.3–100.0) | 0.0 (−55.6–33.3) | 0.06 |

| Travel subscale | 0.0 (−81.1–27.8) | −5.6 (−72.2–100.0) | 0.0 (−77.8–94.4) | 0.03 |

| Social Relationships subscale | −3.3 (−76.7–30.0) | −3.3 (−50.0–76.7) | 0.0 (−60.0–50.0) | 0.19 |

| Emotional subscale | −4.2 (−62.5–33.3) | −4.2 (−45.8–66.7) | 0.0 (−41.7–33.3) | 0.02 |

| Total Score | −13.9 (−269.4–88.9) | −15.7 (−185.83–289.2) | 1.1 (−210.0–159.7) | 0.03 |

|

| ||||

| Change in SF-36‡‡‡ n=166, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Physical Component Summary | 1.4 (0.1–2.6) | 2.3 (0.6–4.0) | −0.8 (−2.4–0.7) | .001 |

| Mental Component Summary | 0.9 (−1.0–2.9) | 0.9 (−0.6–2.4) | −0.2 (−1.9–1.5) | .39 |

|

| ||||

| Change in AUA-7§ n=168, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Total Score | −2.5 (−3.8 – −1.2) | −2.1 (−3.3 – −1.0) | −0.9 (−1.9 – 0.0) | 0.003 |

| Voiding Subscale | −1.0 (−1.8 – −0.2) | −0.5 (−1.1–0.2) | −0.3 (−0.8–0.2) | 0.21 |

| Storage Subscale | −1.5 (−2.3 – −0.8) | −1.7 (−2.4 – −1.0) | −0.6 (−1.3–0.0) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| IPSS QOL§§ “If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary problem the way it is now, how would you feel about that?” (n=171), n (%) | ||||

| Delighted | 2 (3.5%) | 3 (5.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.006 |

| Pleased | 11 (19.0%) | 7 (13.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Mostly satisfied | 14 (24.1%) | 13 (24.5%) | 9 (15.0%) | |

| Mixed | 15 (25.9%) | 19 (35.9%) | 19 (31.7%) | |

| Mostly dissatisfied | 9 (15.5%) | 3 (5.7%) | 14 (23.3%) | |

| Unhappy | 6 (10.3%) | 6 (11.3%) | 14 (23.3%) | |

| Terrible | 1 (1.7%) | 2 (3.8%) | 4 (6.7%) | |

|

| ||||

| Global Perception of Improvement (GPI) (n=171), n (%), Overall leakage is “better” or “much better” vs. ”same”, “worse” or “much worse” | 52/58 (89.7%) | 48/53 (90.6%) | 6/60 (10.0%) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Able to wear less protection now than before treatment (n=171), n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 32 (55.2%) | 22 (41.5%) | 3 (5.0%) | |

| No | 19 (32.8%) | 25 (47.2%) | 52 (86.7%) | |

| Never used protection | 7 (12.1%) | 6 (11.3%) | 5 (8.3%) | |

|

| ||||

| Activity Restriction due to Incontinence (n=170), n (%) | ||||

| Not at All | 37 (63.8%) | 40 (76.9%) | 25 (41.7%) | |

| Some of the time | 20 (34.5%) | 11 (21.2%) | 31 (51.7%) | |

| Most of the time | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.9%) | 4 (6.7%) | 0.003 |

| All of the time | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

|

| ||||

| How disturbing is the leakage of urine? (n=171), n (%) | ||||

| Not at all (including not leaking now) | 16 (27.6%) | 22 (41.5%) | 6 (10.0%) | <0.001 |

| Somewhat disturbing | 40 (69.0%) | 29 (54.7%) | 43 (71.7%) | |

| Extremely disturbing | 2 (3.5%) | 2 (3.8%) | 11 (18.3%) | |

P-values are from ANOVA analyses which determine if there is an overall group difference on each variable.

CI = Confidence Intervals

EPIC = Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite

IIQ = Incontinence Impact Questionnaire

SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey

AUA-7 = American Urological Association Symptom Index

IPSS QOL = International Prostate Symptom Scale Quality of Life question

PSQ = Patient Satisfaction Question

NA = not applicable

Figure 2.

Incontinence Episodes per Week on 7-Day Bladder Diary

Table 3.

Outcomes and Adherence at Six and Twelve Months

| Behavior | Behavior Plus | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Percent Improvement in Incontinence Episodes on 7-Day Bladder Diary, mean (95% CI*) | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 91 | 55.9% (46.1–65.7%) | 52.8% (36.4–69.1%) | .74 |

| Mean episodes per week (95% CI) | 12.6 (8.7–16.6) | 14.6 (7.0–22.1) | |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 81 | 50.4% (39.8–61.1%) | 59.0% (45.0–73.1%) | .32 |

| Mean episodes per week (95% CI) | 13.5 (9.5–17.5) | 9.1 (4.6–13.6) | |

|

| |||

| Change in EPIC,‡ mean (95% CI) | |||

| Urinary Domain | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 98 | 12.2 (9.5–14.9) | 7.2 (4.0–10.4) | .10 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 82 | 12.0 (8.2–15.7) | 9.9 (6.2–13.7) | .49 |

| Incontinence Subscale | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 98 | 14.7 (9.7–19.6) | 10.1 (6.4–13.8) | .19 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 82 | 14.4 (8.9–19.8) | 13.3 (7.7–18.8) | .97 |

|

| |||

| Change in IIQ, ‡‡ median (range) | |||

| Physical Activity subscale | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 97 | −.5.6 (−72.2–61.1) | −5.6 (−83.3–61.1) | .71 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 82 | −5.6 (−77.8–50.0) | −5.6 (−83.3–77.8) | .06 |

| Travel subscale | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 97 | −5.6 (−80.0–22.2) | −5.6 (−61.1–77.8) | .99 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 82 | −2.8 (−72.2–22.2) | −7.8 (−72.2–22.2) | .03 |

| Social Relationships subscale | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 97 | −3.3 (−63.3–26.7) | −4.2 (−64.8–50.0) | .87 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 81 | −3.3 (−56.7–30.0) | −3.3 (−68.1–22.6) | .06 |

| Emotional subscale | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 97 | −6.7 (−66.7–25.0) | −4.2 (−83.3–62.5) | .93 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 81 | 0.0 (−66.7–33.3) | −4.2 (−66.7–54.2) | .10 |

| Total Score | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 97 | −16.9 (−242.2–95.6) | −12.2 (−214.8–188.9) | .92 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 81 | −14.6 (−256.7–99.4) | −19.2 (−238.9–176.8) | .04 |

|

| |||

| Change in SF-36, ‡‡‡ mean (95% CI) | |||

| Physical Component Summary | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 97 | 1.3 (−0.3–2.9) | 1.8 (−0.0–3.7) | .38 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 81 | 0.5 (−1.4–2.3) | 1.1 (−0.7–3.0) | .51 |

| Mental Component Summary | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 97 | −0.8 (−3.5–1.9) | 0.5 (−1.4–2.4) | .18 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 81 | 0.2 (−2.6–3.1) | 0.2 (−1.7–2.2) | .64 |

|

| |||

| Change in AUA-SI§ scores, mean (95% CI) | |||

| Total Score | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 98 | −3.9 (−5.3 – −2.6) | −2.5 (−3.8 – −1.2) | .53 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 84 | −3.4 (−4.9 – −1.9) | −2.1 (−3.2 – −1.1) | .94 |

| Voiding Subscale | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 98 | −1.6 (−2.3 – −0.9) | −0.6 (−1.2–0.1) | .26 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 84 | −1.3 (−2.1 – −0.5) | −0.2 (−0.8–0.4) | .42 |

| Storage Subscale | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 98 | −2.3 (−3.1 – −1.5) | −1.9 (−2.8 – −1.0) | .90 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 84 | −2.1 (−3.0 – −1.2) | −1.9 (−2.7 – −1.1) | .50 |

|

| |||

| IPSS QOL§§ “If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary problem the way it is now, how would you feel about that?” n (%) | .95 | ||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 98 | 2 (4.0%) | 2 (4.2%) | |

| Delighted | 9 (18.0%) | 8 (16.7%) | |

| Pleased | 12 (24.0%) | 12 (25.0%) | |

| Mostly satisfied | 15 (30.0%) | 13 (27.1%) | |

| Mixed | 7 (14.0%) | 10 (20.8%) | |

| Mostly dissatisfied | 3 (6.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | |

| Unhappy | 2 (4.0%) | 2 (4.2%) | |

| Terrible | .13 | ||

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 84 | 2 (4.4%) | 3 (7.9%) | |

| Delighted | 12 (26.1%) | 8 (21.1%) | |

| Delighted | 8 (17.4%) | 17 (44.7%) | |

| Mostly satisfied | 13 (28.3%) | 5 (13.2%) | |

| Mixed | 7 (15.2%) | 4 (10.5%) | |

| Mostly dissatisfied | 3 (6.5%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Unhappy | 1 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Terrible | |||

|

| |||

| Global Perception of Improvement: (GPI) n (%) | |||

| “Better” or “much better” vs. “same”, “worse” or “much worse” | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 94 | 39 (84.8%) | 34 (70.8%) | .11 |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 82 | 42 (91.3%) | 30 (83.3%) | .27 |

|

| |||

| Able to Wear Less Protection Now than Before Treatment | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 95 | .853 | ||

| Yes | 26 (55.3%) | 24 (50.0%) | |

| No | 18 (38.3%) | 20 (41.7%) | |

| Never used protection | 3 (6.4%) | 4 (8.3%) | |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 84 | .913 | ||

| Yes | 25 (54.4%) | 19 (50.0%) | |

| No | 17 (37.0%) | 15 (39.5%) | |

| Never used protection | 4 (8.7%) | 4 (10.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Activity Restriction due to Incontinence, n (%) | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 95 | .05 | ||

| Not at All | 26 (55.3%) | 36 (75.0%) | |

| Some of the time | 20 (42.6%) | 10 (20.8%) | |

| Most of the time | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.2%) | |

| All of the time | 1 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 84 | .002 | ||

| Not at All | 24 (52.2%) | 32 (84.2%) | |

| Some of the time | 22 (47.8%) | 5 (13.2%) | |

| Most of the time | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| All of the time | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

|

| |||

| How Disturbing is the Leakage of Urine? n (%) | |||

| 6 Months Post-Treatment, n = 95 | .89 | ||

| Not at all (including not leaking now) | 14 (29.8%) | 13 (27.1%) | |

| Somewhat disturbing | 31 (66.0%) | 32 (66.7%) | |

| Extremely disturbing | 2 (4.3%) | 3 (6.3%) | |

| 12 Months Post-Treatment, n = 82 | .15 | ||

| Not at all (including not leaking now) | 13 (29.6%) | 19 (50.0%) | |

| Somewhat disturbing | 29 (65.9%) | 17 (44.7%) | |

| Extremely disturbing | 2 (4.6%) | 2 (5.3%) | |

CI = Confidence Intervals

EPIC = Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite

IIQ = Incontinence Impact Questionnaire

SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey

AUA-7 = American Urological Association Symptom Index

IPSS QOL = International Prostate Symptom Scale Quality of Life question

PSQ = Patient Satisfaction Question

At 8 weeks, the Urinary Domain and the Urinary Incontinence Subscale of the EPIC showed significantly greater improvement with Behavioral Therapy (11.5 (95% CI 8.9–14.1) and 13.1 (95% CI 9.1–17.1), respectively) and Behavior Plus (8.4 (95% CI 6.0–10.9) and 12.3 (95% CI 8.4–16.2) compared with Control (2.6 (95% CI 0.6–4.6) and 2.9 (95% CI −0.2–5.9) (Table 2). Compared with Control, Behavioral Therapy and Behavior Plus also showed significant improvement in the total IIQ score, Travel and Emotional IIQ subscales, less burden on the IPSS Quality of Life Question, and declines in total symptom score and urine storage subscale on the AUA-7, (Tables 1 and 2).

Ninety and 91% of participants in Behavioral Therapy and Behavior Plus, respectively, described their leakage as "better" or "much better" overall, compared with 10% of participants in Control. Forty-seven percent of participants in the treatment groups were completely satisfied with their progress. Activity was reported as "not at all restricted" by incontinence in 64% of the Behavior group and 77% of the Behavior Plus group, compared with 42% in the Control group. Leakage was extremely disturbing to 4% of the Behavior and Behavior Plus groups, compared with 18% in the Control group. Concerning pad use, 55% and 42% of participants in the Behavior and Behavior Plus groups reported wearing fewer pads or diapers than before treatment, compared with 5% of participants in the Control group (p’s <.01).

Adherence to exercises and bladder control strategies respectively was 100% and 93% at 8 weeks, 82% and 84% at 6 months, and 91% and 81% at 12 months with no between-group differences. There were two study-related adverse events, 2 of 70 men receiving electrical stimulation developed transient hemorrhoidal irritation.

DISCUSSION

This randomized controlled trial clearly demonstrated that behavioral therapy with pelvic floor muscle exercises, strategies to prevent stress and urge leakage, fluid management, and self-monitoring with bladder diaries is an effective treatment for post-prostatectomy incontinence persisting even years after surgery. Behavioral therapy reduced incontinence frequency, and improved urine storage symptoms (frequency, urgency and nocturia), impact of incontinence on daily activities, and condition-specific quality of life. Based on a PubMed search, the 2008 4th International Consultation on Incontinence report,24 and the 2009 Cochrane Review,25 this is the first randomized, controlled trial of behavioral therapy in men with incontinence persisting more than a year after radical prostatectomy.

While only 16% of men achieved complete continence with behavioral therapy, men with persistent post-prostatectomy incontinence were able to reduce their incontinence frequency by more than half. A recent study determined that a 40% reduction in incontinence frequency was the threshold required to achieve a clinically important improvement on the validated, Incontinence Quality of Life questionnaire.26 The improvement in IIQ scores, which reflects the impact of incontinence on daily life, was 22.9–29.9 exceeding the "minimally important difference" of 6.5–17, reported by Barber, et al.28 A limitation of these minimally important difference data for reduction in incontinence frequency and IIQ are that they were established in women; more work is needed to assess the validity of these incontinence-related outcome measures in men. Minimally important differences have been established for the AUA Symptom Index which measures lower urinary tract symptoms other than incontinence (frequency, urgency, nocturia as well as voiding symptoms). Decreases in AUA-SI score of 2.1–2.5 in our active treatment groups exceeded the threshold for slight improvement (1.9 for patients with baseline scores between 8 and 19 points), but did not exceed the threshold for moderate improvement (4.0 points) reported by Barry, et al.27 Based on the significant decrease in incontinence frequency and the small number needed to treat (n=10) to achieve complete continence with behavioral therapy, these findings have important implications for urologists, primary care providers, and their patients. Resources for locating such centers include the National Association for Continence (www.NAFC.org) and the Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nurses Society (www.WOCN.org).

The addition of biofeedback and electrical stimulation did not increase the effectiveness of the basic behavioral treatment program. However, a limitation of our study is that it was unblinded. Two relevant randomized trials have previously investigated the addition of electrical stimulation and/or biofeedback to pelvic floor muscle exercises in the early post-operative period,29,30 and both found no statistical difference between those active treatment groups. Clinical experience of the authors has shown that these techniques are very useful for teaching patients to locate and exercise their pelvic floor muscles; however, it is unusual to encounter men who cannot learn to control their pelvic floor muscles using verbal coaching during physical examination (Table 1). Thus, the use of biofeedback or electrical stimulation does not appear to be essential in initial therapy for post-prostatectomy incontinence. This makes it more practical, as well as less costly, to disseminate and administer behavioral treatment.

Many of the participants in our trial reported that they had tried pelvic floor muscle exercises after their surgery, but had stopped when they failed to improve sufficiently. Twelve months after starting behavioral treatment in this trial, however, more than 80% of men reported continued adherence to exercises and bladder control strategies. This high adherence rate may have been facilitated by the regular visits and self-monitoring with bladder diaries, as well as the treatment's efficacy. While our study was not designed to test any of the individual components of behavioral therapy other than the technologies of biofeedback and electrical stimulation, we believe that the bladder control strategies are essential to yield optimal behavioral therapy outcomes.

In conclusion, behavioral therapy, including pelvic floor muscle exercises, bladder control strategies, fluid management, and self-monitoring with bladder diaries is an effective treatment for post-prostatectomy incontinence persisting more than 1 year after surgery, and adding biofeedback and electrical stimulation did not increase effectiveness. Behavioral therapy should be offered to men with persistent post-prostatectomy incontinence, since it can yield significant, durable improvement in incontinence and quality of life, even years after radical prostatectomy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01 DK60044 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Department of Veterans Affairs Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration: The trial was registered at Clinical Trials.gov, # NCT00212264 under the title “Conservative Treatment of Postprostatectomy Incontinence” prior to initiation.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancers Facts & Figures–2008. [Accessed November 21, 2009]; at: www.cancer.org.

- 2.Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, Li L, et al. Five-year Urinary and Sexual Outcomes after Radical Prostatectomy: Results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154637.38262.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ficazzola MA, Victor NW. The etiology of post-radical prostatectomy incontinence and correlations of symptoms with urodynamic findings. J Urol. 1998;160:1317–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore KN. The early post-operative concerns of men after radical prostatectomy. J Advanced Nursing. 1999;29:1121–1129. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. AMS Sphincter 800™ Urinary Prosthesis - P000053. [Accessed November 21, 2009]; at: www.fda.gov/cdrh/pdf/p000053.html.

- 6.Migliari R, Pistolesi D, Leone P, Viola D, Trovarelli S. Male bulbourethral sling after radical prostatectomy: intermediate outcomes at 2 to 4-year followup. J Urol. 2006;176:2114–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romano SV, Metrebian SE, Vaz F, et al. Long-term results of a phase III multicentre trial of the adjustable male sling for treating urinary incontinence after prostatectomy: minimum 3 years. Actas Urol Esp. 2009;33:309–14. doi: 10.1016/s0210-4806(09)74146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgio KL, Goode PS, Urban D, et al. Preoperative Biofeedback Assisted Behavioral Training to Decrease Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Urol. 2006;175:196–201. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filocamo MT, Li Marzi V, Del Popolo G, et al. Effectiveness of Early Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation Treatment for Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence. Eur Urol. 2005;48:734–738. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Kampen M, De Weerdt W, Van Poppel H, De Ridder D, Feys H, Baert L. Effect of Pelvic-Floor Re-education on duration and Degree of Incontinence after Radical Prostatectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Lancet. 2000;355:98–102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03473-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manassero F, Traversi C, Ales V, et al. Contributions of Early Intensive Prolonged Pelvic Floor Exercises on Urinary Continence Recovery After Bladder Neck-Sparing Radical Prostatectomy: Results of a Prospective Controlled Randomized Trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:985–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.20442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariotti G, Sciarra A, Gentilucci A, et al. Early Recovery of Urinary Continence After Radical Prostatectomy Using Early Pelvic Floor Electrical Stimulation and Biofeedback Associated Treatment. J Urol. 2009;181:1788–93. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erikson BC, Mjolnerod OK. Changes in urodynamic measurements after successful anal electro-stimulation in female urinary incontinence. Br J Urol. 1987;59:45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1987.tb04577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MFF, S E, McHugh PR. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stothers L, Thom D, Calhoun EA. Urinary Incontinence in Men. [accessed 9/16/2010];Urologic Diseases in America. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000155503.12545.4e. http://www.kidney.niddk.nih.gov/statistics/uda/Urinary_Incontinence_in_Men-Chapter06.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Locher JL, Goode PS, Roth DL, Worrell RL, Burgio KL. Reliability assessment of the bladder diary for urinary incontinence in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M32–5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.1.m32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockett ATK, Khoury S, Aso Y, Chatelain C, Denis L, Griffiths K, Murphy G, editors. Proceedings of the First International Consultation on Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Jersey, Channel Islands: Scientific Communications International Ltd; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, McClish D, Fantl JA. Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:291–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00451721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore KN, Jensen L. Testing of the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7) with Men after Radical Prostatectomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2000;27:304–12. doi: 10.1067/mjw.2000.110623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and Validation of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) for Comprehensive Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Men with Prostate Cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgio KL, Goode PS, Richter HE, Locher JL, Roth DL. Global Ratings of Patient Satisfaction and Perceptions of Improvement with Treatment for Urinary Incontinence: Validation of Three Global Patient Ratings. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25:411–7. doi: 10.1002/nau.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence: 4th International Consultation on Incontinence. Plymouth, UK: Health Publication Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter KF, Moore KN, Glazener CMA. Conservative management for post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence (Review), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001843.pub3. Art. No.: CD001843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yalcin I, Peng G, Viktrup L, Bump RC. Reductions in stress urinary incontinence episodes: what is clinically important for women? Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:344–347. doi: 10.1002/nau.20744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barry MJ, Williford W, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association Symptom Index and the Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995;154:1770–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barber MD, Spino C, Janz NK, et al. The minimum important differences for the urinary scales of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;299:580.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wille S, Sobottka A, Heidenreich A, Hofmann R. Pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation and biofeedback after radical prostatectomy: results of a prospective randomized trial. J Urol. 2003;170:490–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000076141.33973.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore KN, Griffiths D, Hughton A. Urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial comparing pelvic muscle exercises with or without electrical stimulation. BJU Int. 1999;83:57–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]