Abstract

Introduction

The development of interprofessional collaboration is of great significance for facilitating the flow of information and provision of collaborated services. In fact, only one single profession cannot respond to all demands. Thus, this study was aimed to investigate clinical nurse-physician collaboration in Iran.

Methods

This study was performed with nurses and physicians of university hospitals affiliated to Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran, during September 2013-March 2015, using grounded and synthesis theory. The data were obtained using semi-structured interviews and field notes, and MAXQ DA version 10 was employed for data analysis.

Results

The core variable was defined as “management of strategic goals”, and the main categories included perception of challenging organizational structures, providing a comprehensive supportive net for patients, seeking professional communication, and building solid confidence. Based on views of the participants, they were aiming to apply a stress management strategy, while maintaining their position in the organization, by making passive compromises to protect themselves against the perceived threats.

Conclusion

The participants were trying to overcome barriers through reducing and managing the tension, while maintaining their position in the organization using forced, passive coping strategies to protect themselves against the perceived threats.

Keywords: Grounded theory, Interprofessional relations, Nurses, Physicians, Collaboration

1. Introduction

Interprofessional collaboration is not a new concept in the field of medical sciences (1). Researchers believe that no singular profession operating alone, can respond to all care demands (2). Collaboration is necessary to promote patient care, and is associated with enhanced patient outcome (3). A new culture supporting behavior regarding cooperation among nurses and physicians, seems to be mandatory, to merge their unique strengths and to promote patient consequences (4). The development of interprofessional collaboration is an important issue, which can facilitate transfer of information and provision of coordinated services. Effective collaboration among team members in clinical settings is essential for providing safe and reliable care (5). The evidence demonstrates that interprofessional collaboration among medical team members is one of the main factors preventing patient injury and organizational conflicts (6). Currently, studies underscore that nurses have lower satisfaction with physician-nurse cooperation than physicians do (7). The basic barrier to improving patient safety and reducing costs is a lack of collaboration among team members (8). Previous studies indicated considerable differences in physician-nurse mutual collaboration (9). Defective collaboration among team members is responsible for medical errors in sixty percent of the cases (2). The scarcity of domestic studies based on a qualitative approach and grounded theory, and the researcher’s several years of experience in Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran, instigated us to perform this study to understand the differences in organizational backgrounds, structures, and behavior regarding cooperation between clinical groups. Qualitative and quantitative studies were carried out on interdisciplinary collaboration, but the dynamic of this collaboration is context-dependent. Collaboration is an inter-human process, in which several factors mediate communication among professionals (10). Collaboration is a social process hinged on human interaction, and qualitative approaches are applied, for the study of this phenomenon (11). Grounded theory is a qualitative method for shedding light on social processes, one of the main applications of which, is where there is a paucity of information about a phenomenon (12). Using this theory, we aimed to explain how physicians and nurses collaborate with each other.

2. Material and Methods

In the present study, grounded theory was applied; in this study, researchers aim to explain a certain phenomenon through profound evaluation of people’s experiences, clinical performances, behavior, beliefs, and attitudes as they occur in real life (13). In this study, interviewing and writing field notes were employed as data collection methods.

2.1. Setting and participants

We carried out the study in university hospitals affiliated to Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran, during September 2013-March 2015. Data collection was continued until reaching data saturation. The participants were twenty two nurses and physicians (Table 1), who met the inclusion criteria. The subjects could resign from the study at any time at their will. To achieve maximum diversity, male and female individuals with different specialties and clinical experiences, and working in different shifts were interviewed. The inclusion criteria were 1) nurses with at least one year’s clinical experience, 2) physicians with one year’s clinical experience, and 3) willingness to participate in the study.

Table 1.

Individual characteristics of the participants

| Row | Age (year) | Gender | History of work (Year) | Department | Specialty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38 | Male | 15 | Oncology | Nurse |

| 2 | 40 | Female | 18 | Pediatric emergency | Nurse |

| 3 | 45 | Female | 23 | Surgical | Nurse |

| 4 | 40 | Female | 6 | Oncology | Oncologist |

| 5 | 35 | Female | 11 | Heart | Nurse |

| 6 | 28 | Female | 5 | Urology | Nurse |

| 7 | 35 | Female | 10 | Heart emergency | Nurse |

| 8 | 37 | Female | 12 | Emergency | Nurse |

| 9 | 37 | Female | 5 | Internal emergency | Internal medicine |

| 10 | 51 | Male | 10 | Burn | Surgical plastic |

| 11 | 37 | Female | 15 | Internal emergency | Nurse |

| 12 | 42 | Male | 18 | Oncology | Nurse |

| 13 | 38 | Male | 7 | Oncology | Oncologist |

| 14 | 44 | Male | 15 | Neonatal intensive care unit | Neonatology |

| 15 | 45 | Male | 14 | Pediatric | Pediatrician |

| 16 | 40 | Female | 18 | Cardiac care unit | Nurse |

| 17 | 43 | Male | 16 | Toxicology | Toxicologist |

| 18 | 34 | Female | 3 | Nephrology | Nephrology (resident) |

| 19 | 35 | Male | 4 | Internal neurology | Neurology (resident) |

| 20 | 34 | Female | 3 | Rheumatology | Rheumatology (resident) |

| 21 | 47 | Female | 17 | Internal | Internal medicine |

| 22 | 33 | Male | 10 | Neurology emergency | Nurse |

2.2. Data collection

The data were collected using semi-structured interviews and field notes. After receiving an introductory letter from the university Ethics Committee, time and location of the interviews were coordinated with the participants, and then the interviews were initiated. Interviews were held in one or two 45- to 60-minute sessions.

2.3. Data analysis

To analyze the data, Strauss and Corbin’s method was employed. In the open coding stage, the contents of the tapes were reviewed and re-read several times and were transcribed. The researcher scrutinized the data, line by line and word by word to identify the main concepts in each line and paragraph; subsequently, each sentence was assigned a code. Afterwards, the codes were preliminarily categorized and similar ones were grouped in one single category.

In axial coding, constant data analysis was conducted by focusing on the causal conditions, contexts, and consequences of the phenomenon, as well as action/interaction strategies; the codes were then grouped around a common axis and the relation among different categories and subcategories were determined. Finally, in selective coding, the frame of theory and social processes were revealed by integrating and refining the categories.

The interviews continued with open-ended questions; some of the main questions were as follows:

How is collaboration among nurses and physicians shaped?

Can you provide an example of the collaboration among you and physicians? Or can you give an example of the collaboration among you and nurses?

Afterwards, in order to form a theory and reveal the essence of the phenomenon, some specifying questions were asked as follows:

What do you mean by...?

Can you clarify it further? How?

The interviews were recorded and continued until data saturation was reached. After the end of each interview, the recorded data were immediately transcribed and copied. Data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously. For registering, categorizing, and analyzing the data, Max Q, version 10 was used.

2.4. Ethical considerations

Before initiating the study, permission was obtained from the university’s Ethics Committee and an introductory letter was presented to the authorities of the respective hospitals. Considering ethical issues, written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

2.5. Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness of the data was established, based on Lincoln and Goba criteria through prolonged engagement with the data and participants, using member and peer checking. The outcomes of the study were checked by expert supervisors and advisors as directors of the study. Memoing and field note writing were also used for credibility. For the purpose of auditing, all stages of the study were described in detail so that an outside observer was able to do the audits according to these documents.

3. Results

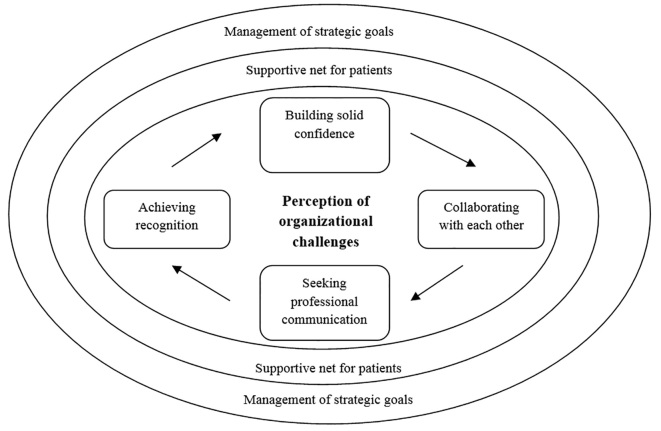

A total of 1,954 primary codes were extracted from twenty two interviews in the open coding stage. After reducing and removing repeated codes, 1,234 codes were obtained. By using constant comparative analysis, the primary codes were organized and categorized into eighty seven primary categories. In the axial coding stage, the primary categories were integrated based on their similarities and differences. In this stage, four main categories and sixteen sub-categories were extracted. Subsequently, by relating different categories and clarifying the social processes among individuals, the study theory was formed and the main story line was defined. “Perception of challenging organizational structures” was considered as the contextual condition and “a comprehensive supportive net for patients” was deemed as the causal condition. Furthermore, “building solid confidence” and “seeking professional communication” were recognized as action/interactional strategies. The outcome of this collaboration was “management of strategic goals”, which was defined as the core variable.

3.1. Building solid confidence

This category consists of the following sub-categories: “knowing each other”, “mutual understanding of the shortcomings”, “ability to understand each other”, and “boosting updated knowledge”.

3.1.1. Knowing each other

In order for people to work together and trust each other, they must begin to know each other. In fact, the relationship and the cooperation among nurses and physicians are based on trust and mutual recognition. In this respect, a participant noted: “Well, in every relationship, it is necessary that both parties try to trust and respect each other in order to build a relationship. After building mutual trust, I’ll try to provide them what they need. I can inform them of certain issues and help them with patient care. Trust and reliability are built upon the recognition of conditions by each side of the interaction (p 22).”

3.1.2. Mutual understanding of the shortcomings

Based on the experience of the participants, one of the effective variables in collaboration is accurate understanding of the shortcomings. In many cases, purposeful collaboration is compromised by several factors. If the parties have a thorough understanding of each other’s limitations, misunderstandings will be eliminated and collaboration will continue without any tension. In this regard, one participant stated: “Another issue is the inadequate number of nursing staff, which leads to inadequate quality of services. In other words, the limited number of nurses, compared to patients, and the absence of standard conditions in hospital wards endanger healthcare quality. Thus, the idea that a nurse should be an effective care provider is questioned, since the nurse is involved with many patients and is influenced by various circumstances; naturally, the quality of their work is affected by this matter, and their attitudes change (p 15)”.

3.1.3. Understanding each other’s abilities

The participants held that individuals with more skills and experience can collaborate more effectively, compared to others. Most of the cases stated that by having a thorough understanding of each other’s formal and practical skills (recognizing each other’s abilities), mutual trust could be developed. Therefore, being experienced and skillful in collaborative fields is known as a key feature.

3.1.4. Boosting updated knowledge

Information exchange occurs spontaneously in the process of collaboration. Under these circumstances, information and knowledge of both parties can be refreshed. Therefore, both parties will expand and promote their collaboration to refresh their knowledge.

3.2. A comprehensive supportive net for patients

Another derived category was a comprehensive supportive net of patients, which appeared as a major category. Four sub-categories were derived as follows: “protecting patients’ rights”, “empathizing with the patients”, “adhering to personal and organizational commitments”, and “struggling on collaborative grounds”. All the participants agreed upon these themes. In fact, their main motivation was provision of support for patients in different physical, mental, spiritual, and social aspects.

3.2.1. Protecting patients’ rights

Physicians and nurses take patients’ demands and needs into account in the process of collaboration, and prioritize a patient’s interests above their own personal interests. They believed that any action, which could negatively affect patients’ interests, should be avoided. Enhancing the speed of healthcare services, raising awareness, and considering human rights, according to the Patient’s Bill of Rights, were among the most important concepts.

3.2.2. Empathy with patients

Empathy and sympathy with patients, treating them as family members, working wholeheartedly, alleviating patients’ concerns, and understanding their problems were among the mentioned concepts. As one of the physicians remarked: “Patient care is very important. I mean, you should treat the patient like family and take care of him as you would for a family member (p 13)”.

3.2.3. Adherence to personal and organizational commitments

Participants also mentioned that having professional conscience and organizational discipline as well as being responsible are necessary for enforcing patient rights. In this regard, one of the participants remarked: “The main factor that shapes the relationship among doctors and nurses is consciousness, which also benefits patients; however, this value is sometimes neglected. In organizations, either private or public, major progress is made if the staff are conscious about professional ethics. For instance, we have doctors who admit the patient to the ward, but refer the patient to first or second-year medical residents, despite being on call; these patients are discharged later without any further visits by the doctor (p 7)”.

3.3. Struggles on collaborative grounds

The scope of clinical collaboration is vast and includes different areas of care, treatment, education, counseling, and collaborating. Each of these areas has its own significant shortcomings and the parties struggle with these problems until optimal collaboration is achieved. Overall, these problems and conflicts vary in different clinical fields.

3.3.1. Seeking professional communication

In some studies, the concept of collaboration is frequently referred to as “interaction” (10, 11). However, interaction is one of the concepts involved in collaboration, which is preferred by nurses and physicians (12). “Having an active interaction”, “understanding each other”, “applying communication skills”, “having purposeful professional communication”, and “contexts of threatening communication” were its sub-categories. On this subject, a resident remarked: “The circumstances at the ward encourage me to have a better performance and be more collaborative. I mean if the personnel ask me for something and I feel that my patient benefits from it, I will not hesitate a moment and will gladly do it. These sorts of interactions promote the use of hospital facilities towards improving patient outcomes (p 17)”.

3.3.2. Understanding each other

Purposeful communication is effective in the process of care provision and treatment and leads to synergy. Overall, professional communication facilitates collaboration, and benefits both parties involved in the interaction. “Nurse-physician interaction”, “complementing each other’s roles”, and “working as a unit” were the concepts derived from the interviews. One of the participants said: “Experience shows that the orders of physicians with a commanding and loud tone will be eventually discarded; I mean the staff and nurses will unconsciously ignore their commands and become defensive against them. On the other hand, if the interactions are friendly and physicians do not underestimate nurses, their requests will not be disregarded (p 9)”.

3.4. Perception of challenging organizational structures

This category was composed of four sub-categories including: “stressful work conditions”, “passive coping with organization”, “overcoming belief on organizational atmosphere”, and “different world of colleagues”.

3.4.1. Stressful work conditions

One of the factors mentioned by most participants from different clinical sections was work overload. The disproportionate number of nursing staff and patients, limited human resources, lack of equipment and technology, and an increasing number of hospital admissions were considered as the major causes of work overload. In this regard, one of the participants remarked: “Well, humans have a certain capacity. Sometimes, the workload is so high. I do not know the exact numbers, but some days, the number of patients increase from 20 to 40–45 and everyone starts complaining since the workload is not specified. The nurses’ workload is not determined, that is, the limits have not been defined (p5)”.

3.4.2. Employing passive coping strategies for organizational structures

The unsupportive atmosphere of organizational structures was one of the complaints of the participants. The absolute authority of the hospital management board and the dominant treatment paradigm are major challenges in fostering a collaborative, effective atmosphere. Unequal institutional power, unfair income differences, non-use of motivational tools, and absence of clear strategies deteriorated the situation for collaboration. Under these unfavorable circumstances, individuals make passive compromises in order to maintain their position in an organization. If these circumstances persist, they may lead to personal, organizational, and social harms. As one of the participants pointed out: “The involved organizations fuel the differences, either economically or cooperatively. As one’s social rank rises, the disputes become more intensified. Those with lower ranks are eager to reach harmony, but this does not happen at higher ranks. Maybe, the reason is they do not care enough, because they know nothing about the details and they don’t try to make compromises (p 17)”.

3.4.3. Management of strategic goals (the core category)

This concept was highlighted and repeated throughout the study, by linking different categories; it also directly or indirectly affected other categories. This core category represented the essence of collaboration in clinical practice and justified all clinical attempts and decisions. In fact, individuals seek professional communication or attempt to build mutual trust to access strategies that ensure everyone’s interest. Patient comfort, elimination of repetition, prompt discharge of patients, reduced costs, and increased patient satisfaction were discussed as the outcomes of positive collaboration. All individuals involved in the collaboration including the patient and family may benefit from the collaboration, and loss of social capital will be prevented (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The process of nurse-physician collaboration

4. Discussion

Collaboration is a complicated process that does not occur automatically (14). This study provides insight into the process of interdisciplinary collaboration in the Iranian clinical care setting. We evaluated the process of nurse-physician collaboration with respect to the three aspects of structure, process, and outcome. In some studies, educational attitudes and contexts as well as external factors such as health care systems and economic pressure were considered as structures of collaboration. Interactions, patient referral, and leadership were mentioned as the major processes affecting collaboration. Also, enhancing satisfaction and providing opportunities for development and organizational commitment were regarded as the outcomes of this concept (15, 16).

4.1. Structure of collaboration

In the current study, the structure of collaboration was the most challenging concept as was stated by the participants. Both groups referred to having a comprehensive program in clinical practices as a guide and guarantee for the professional interests of both parties in the interaction. The participants recognized the atmosphere of organizations as unsupportive. The inhibiting factors for collaboration were the unsupportive atmosphere of formal organizations, non-use of motivational tools, and lack of feedback and a specific mechanism for promoting collaboration. Given physicians’ absolute authority and at the same time, the friendly relationships in different departments among the staff, individuals try to reduce and manage the tension, and maintain their position in the organization by making passive compromises to protect themselves against perceived threats. By extracting and organizing the mentioned concepts, absence of a collaborative structure was identified. In fact, the absence of a defined structure can have negative personal and organizational effects and may waste social capital. In a former study, the structure of interdisciplinary collaboration, philosophy and beliefs, administrative leadership, and resources were discussed (17). In some studies, physical, social, and organizational barriers were deems as obstacles to professional collaboration. (18, 19).

4.2. The process of collaboration

Many authors defined collaboration as a process. For instance, it was defined as “positive communication among team members to respond to client needs” (20). Also, it was characterized as a complicated and dynamic process, which is based on trust, familiarity, and goal-sharing (21). In another study, concepts of patient management, clinical reasoning, and decision-making processes were underscored as three main themes of interprofessional collaboration (22). In the present study, the process of collaboration included searching for professional communication, which is based on professional ethics, rules, and responsibilities to achieve recognition relative to each other and building solid confidence. These categories were aimed towards finding a common strategy for improving quality of healthcare provision. In one study, which utilized the thematic content analysis approach, residents’ and nurses’ perceptions and expectations of their own and each other’s disciplinary roles were examined. In that study, three main categories obtained from the data included patient management, decision-making process, and roles of team members. In the mentioned study, the derived concepts were different from those of the present study, this discrepancy could be due to diverse study settings and approaches (23). Another study was carried out to determine the social processes involved in nurse-physician collaboration. The concept of “moving toward a common goal” was extracted as the core category. In the mentioned study, collaboration occurred in nine stages (11). The extracted concepts and categories were different from those of the current study, although the core category was very similar to that of our study. The differences in the derived concepts and categories seem to be typical as they are absolutely context-dependent. Overall, the main theme in the process of collaboration is associated with common organizational objectives for which everyone plans and thrives. Therefore, finding this concept is highly expected in different environments. In another study, in primary care setting, the process of collaboration was described as a facilitating factor in interdisciplinary teamwork. In that study, ethnography approach was applied, which requires regular team meetings, team building activities, and ongoing on-the-job training (24).

4.3. Consequences of collaboration

Is collaboration a process or a consequence? To recognize collaboration as an outcome, its results should be considered (11). Outcomes are benchmarks for determining the level of collaboration between partners. In fact, effective collaboration exerts positive effects on outcomes. Most researchers are of the opinion that the collaboration among health care professionals can improve the outcomes of health care services. As was noted in other studies, great attention was focused on outcomes in the process of clinical nurse-physician collaboration. In fact, if collaboration is perfectly shaped, similar outcomes would be expected, regardless of the context. In the present study, the outcomes of collaboration included optimal care, reduced costs and complications, shortened length of hospital stay, and satisfaction of both parties. In a former study, the major collaboration outcomes included improved communication, patient satisfaction, optimum time management, and improved education (25). In a study by Badger et al., improved communication, enhanced confidence, and increased knowledge were outcomes of the collaboration process (26).

4.4. Strengths and limitations

This study is based on grounded theory approach. The grounded theory approach has an added advantage allowing analysis beyond theme generation. It offers a technique to examine the relationship between the variables depicting the dynamic process of healthcare provision (27). Workplace collaboration depends on various factors, and those volunteering to participate may be more interested in collaboration. The main limitation of this study, was not using observation as a data collection method.

5. Conclusions

In this study, some of the presented concepts include development of sustainable confidence, understanding the challenging organizational structures, and providing a comprehensive safety net for patients, which are of great significance in professional communication. The theory of management of strategic objectives of collaboration between physicians and nurses sheds light on its aspects, features, and consequences. Physicians and nurses can improve the quality of care and treatment through management of common strategic objectives and having an accurate understanding of the urgency, importance, and the process of collaboration using the participants’ experience. To demonstrate deep aspects of interprofessional collaboration, we recommended conducting further studies on the subject of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary cooperation in educational, research, and clinical areas between nurses and other specialized fields.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Deputy of Research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences for financial support. Moreover, we extend our gratitude to the participants of the study. This article is part of a nursing PhD thesis (approval No.: 922126) and is funded by the Deputy of Research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

iThenticate screening: August 02, 2016, English editing: September 20, 2016, Quality control: April 12, 2017

Conflict of Interest:

There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Authors’ contributions:

All authors contributed to this project and article equally. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Petri L. Concept analysis of interdisciplinary collaboration. Nurs Forum. 2010;45(2):73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin JS, Ummenhofer W, Manser T, Spirig R. Interprofessional collaboration among nurses and physicians: making a difference in patient outcome. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140:13062. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller CA, Tetzlaff B, Theile G, Fleischmann N, Cavazzini C, Geister C, et al. Interprofessional collaboration and communication in nursing homes: a qualitative exploration of problems in medical care for nursing home residents-study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(2):451–7. doi: 10.1111/jan.12545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair DM, Fitzpatrick JJ, McNulty R, Click ER, Glembocki MM. Frequency of nurse-physician collaborative behaviors in an acute care hospital. J Interprof Care. 2012;26(2):115–20. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2011.637647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyndon A, Zlatnik MG, Wachter RM. Effective physician-nurse communication: a patient safety essential for labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(2):91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ten Have EC, Hagedoorn M, Holman ND, Nap RE, Sanderman R, Tulleken JE. Assessing the quality of interdisciplinary rounds in the intensive care unit. J Criti Care. 2013;28(4):476–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenaszchuk C, Wilkins K, Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Russell A. Nurse-physician relations and quality of nursing care: findings from a national survey of nurses. Can J Nurs Res. 2010;42(2):120–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Titzer JL, Swenty CF, Hoehn WG. An interprofessional simulation promoting collaboration and problem solving among nursing and allied health professional students. Clin Simul Nurs. 2012;8(8):325–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2011.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Leary KJ, Ritter CD, Wheeler H, Szekendi MK, Brinton TS, Williams MV. Teamwork on inpatient medical units: assessing attitudes and barriers. Qual Safety Health Care. 2010;19(2):117–21. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.028795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaldheim HKA, Slettebø Å. Respecting as a basic teamwork process in the operating theatre-A qualitative study of theatre nurses who work in interdisciplinary surgical teams of what they see as important factors in this collaboration. Nord Sygeplejeforskning. 2016;5(01):49–64. doi: 10.18261/issn.1892-2686-2016-01-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fewster Thuente L. A grounded theory of nurse-physician collaboration. Loyola University Chicago; 2011. Working together toward a common goal. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berge JM, Loth K, Hanson C, Croll - Lampert J, Neumark - Sztainer D. Family life cycle transitions and the onset of eating disorders: a retrospective grounded theory approach. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(9–10):1355–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urquhart C. Grounded theory for qualitative research: A practical guide. Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore J, Prentice D. Collaboration among nurse practitioners and registered nurses in outpatient oncology settings in Canada. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(7):1574–83. doi: 10.1111/jan.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, Dunn S, Pluye P, Frosch D, et al. Validating a conceptual model for an inter - professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. J Evalu Clin pract. 2011;17(4):554–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedwell WL, Wildman JL, Diaz Granados D, Salazar M, Kramer WS, Salas E. Collaboration at work: An integrative multilevel conceptualization. Hum Res Manag Rev. 2012;22(2):128–45. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bender M, Connelly CD, Brown C. Interdisciplinary collaboration: The role of the clinical nurse leader. J Nurs Manag. 2013;21(1):165–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young HM, Siegel EO, McCormick WC, Fulmer T, Harootyan LK, Dorr DA. Interdisciplinary collaboration in geriatrics: Advancing health for older adults. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59(4):243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Organization WH. Interprofessional collaborative practice in primary health care: nursing and midwifery perspectives. 2013;13:24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nugus P, Greenfield D, Travaglia J, Westbrook J, Braithwaite J. How and where clinicians exercise power: Interprofessional relations in health care. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(5):898–909. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gotlib Conn L, Kenaszchuk C, Dainty K, Zwarenstein M, Reeves S. Nurse-Physician Collaboration in General Internal Medicine: A Synthesis of Survey and Ethnographic Techniques. Health Interprof Pract. 2014;2(2):2. doi: 10.7772/2159-1253.1057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller-Juge V, Cullati S, Blondon KS, Hudelson P, Maître F, Vu NV, et al. Interprofessional collaboration between residents and nurses in general internal medicine: a qualitative study on behaviours enhancing teamwork quality. PloS One. 2014;9(4):96160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller-Juge V, Cullati S, Blondon KS, Hudelson P, Maître F, Vu NV, et al. Interprofessional collaboration on an internal medicine ward: role perceptions and expectations among nurses and residents. PloS One. 2013;8(2):57570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al Sayah F, Szafran O, Robertson S, Bell NR, Williams B. Nursing perspectives on factors influencing interdisciplinary teamwork in the Canadian primary care setting. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(19–20):2968–79. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes JJ. Improving Interdisciplinary Communication to Improve Patient Satisfaction. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badger F, Plumridge G, Hewison A, Shaw KL, Thomas K, Clifford C. An evaluation of the impact of the Gold Standards Framework on collaboration in end-of-life care in nursing homes. A qualitative and quantitative evaluation. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(5):586–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Low LL, Tong SF, Low WY. Selection of Treatment Strategies among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Malaysia: A Grounded Theory Approach. PloS One. 2016;11(1):0147127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]