Abstract

Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (SpA) and radiographic SpA (also known as ankylosing spondylitis) are currently considered as two stages or forms of one disease (axial SpA). The treatment with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) inhibitors has been authorized for years for ankylosing spondylitis. In recent years, most of the anti-TNFα agents have also been approved for the treatment of nonradiographic axial SpA by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and similar authorities in many countries around the world (but not in the US), increasing the number of possible therapies for this indication. Data from several clinical trials have demonstrated the good efficacy and safety profiles from those anti-TNFα agents. Presently, a large number of patients achieve a satisfactory clinical control with the current therapies, however, there remains a percentage refractory to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and TNFα inhibitors; therefore, several new drugs are currently under investigation. In 2015, the first representative of a new class of biologics [an interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitor] secukinumab, was approved for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis; a clinical trial in nonradiographic axial SpA is currently underway. In this review, we discuss the recent data on efficacy and safety of TNFα-inhibitors focusing on the treatment of nonradiographic axial SpA.

Keywords: spondyloarthritis, treatment, TNFα

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease primarily affecting the axial skeleton (spine and sacroiliac joints) and frequently associated with HLA-B27. Patients with axSpA can also develop other typical SpA features like peripheral arthritis (usually mono- or oligoarthritis of the lower limbs), enthesitis and dactylitis as well as extra-articular manifestations such as psoriasis, anterior uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease.1 AxSpA is characterized by the presence of active inflammation in the sacroiliac joints and possibly the spine, which manifests as back pain and stiffness. In advanced disease, repair processes following active inflammation might lead to new bone formation in the spine with limitation of spinal mobility and functional impairment.2

Depending on the presence or absence of definite radiographic sacroiliitis, axSpA is divided into radiographic SpA (also called ankylosing spondylitis, AS) or nonradiographic SpA (nr-axSpA), respectively. Definite radiographic sacroiliitis is defined by grade II and higher bilaterally or grade III and higher unilaterally according to the grading system of the modified New York (mNY) criteria.3 The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria for axSpA cover both disease subtypes.4 There is the tendency to accept that both forms are stages of one disease; several studies have shown that nr-axSpA and AS patients have similar characteristics in terms of burden of disease.5–7 The introduction of this current concept of axSpA has been an important step towards earlier diagnosis and subsequently earlier treatment, specifically for the use of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) inhibitors, which were approved for AS and could additionally obtain the indication for nr-axSpA.

In the current work, we review the recent data on efficacy and safety of TNFα-inhibitors in the treatment of nr-axSpA in the context of current and future therapeutic options for the entire group of axSpA.

Search strategy

We searched for original articles and reviews in Medline (via PubMed) published between 1 January 2007 and 31 January 2017 using the term ‘axial spondyloarthritis’ in combination with the term ‘treatment.’ We focused on studies that included a clearly defined population of ‘nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis,’ but did not exclude commonly referenced older publications related to the treatment of a broader population of SpA.

Treatment of nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis according to the current guidelines

According to the current ASAS/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations (update 2016) for patients with axSpA (both radiographic and nonradiographic), first-line therapy in symptomatic patients includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in combination with patient education and regular exercise/physiotherapy.8 Local corticoids can be used for the therapy of peripheral symptoms but systemic glucocorticoids are not recommended for long-term therapy in axSpA.8 Although the use of conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate,9 leflunomide,10 and sulfasalazine11 has been extensive in the last decades, as they seemed to bring some reduction of symptoms in the peripheral involvement, they have not proven effective for axial manifestations in SpA.

Patients with axSpA whose disease activity remains high despite the adequate therapeutic trial of at least two different NSAIDs in maximal doses for at least 4 weeks in total, may be candidates for so-called biological DMARDs.8 High disease activity is defined by the ASAS group as the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) ⩾ 2.1 or the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) ⩾ 4.8 Patients without definite radiographic sacroiliitis (i.e. patients with nr-axSpA) are additionally required to have either an elevated level C-reactive protein (CRP) or presence of active inflammation on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the sacroiliac joints.8 Currently, only two classes of biological DMARDs showed efficacy and are, therefore, recommended (according to the ASAS/EULAR recommendations) for the treatment of axSpA: TNFα inhibitors and the interleukin (IL) 17 inhibitor secukinumab,8 although there are differences in the approval status of these drugs in AS and nr-axSpA (see below), as well as local guidelines, varying from country to country, sometimes limiting therapeutic options, especially in nr-axSpA.

The American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of AS and nr-axSpA are similar to the ASAS/EULAR recommendations, but do not include IL-17 blockade as a therapeutic option, since they were developed prior to approval of secukinumab for the treatment of AS.12

Currently there are five anti-TNFα agents available for the treatment of AS: adalimumab, golimumab, infliximab (monoclonal antibodies against TNFα), certolizumab pegol (a PEGylated Fab fragment of a monoclonal antibody against TNFα), and etanercept (a soluble TNF-receptor construct). They have all demonstrated strong and similar efficacy in clinical trials in active AS with substantial improvement of the symptoms (ASAS40 response in 40–50% of the patients; 50% improvement of the BASDAI achieved by 50–60% of patients) as well as clear reduction of active inflammation on MRI.13–17

Since 2012, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended approval of four TNFα-inhibitor agents (Table 1) for the treatment of nr-axSpA: adalimumab,18 certolizumab pegol,17 etanercept,19 and golimumab20 after having conducted respective phase III trials (Table 2). No phase III trial has been conducted for infliximab, consequently, infliximab is indicated formally only in active AS.

Table 1.

Antitumor necrosis factor-α agents approved* for treatment of nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis.

| Adalimumab | Certolizumab pegol | Etanercept | Golimumab | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule | Human monoclonal antibody | PEGylated Fab fragment of monoclonal antibody | Fusion protein | Human monoclonal antibody |

| Manufacturing company | Abbvie | UCB | Amgen | Janssen / Johnson & Johnson |

| Dosage for axSpA | 40 mg SC every 2 weeks | Initial dose of 400 mg SC at week 0, 2 and 4, and followed by 200 mg SC every 2 weeks or 400 mg SC every 4 weeks | 50 mg SC every week | 50 mg SC once a month |

| Application | Subcutaneous | Subcutaneous | Subcutaneous | Subcutaneous |

| Biological half-life | 14 days | 14 days | 2.9 days | 12 days |

| Drug approval * for nr-axSpA | June 2012 | September 2013 | June 2014 | June 2015 |

In the EU and many other countries, but not in the US.

axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; nr-axSpA, nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis; SC, subcutaneous.

Table 2.

An overview of the studies on the efficacy of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis.

| Name of study | Design of study | Duration | Study population | Active drug | Number of patients | Endpoints | Main results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study by Haibel et al. | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled | 12 weeks double blind + open-label extension up to week 52 |

Active nr-axSpA (BASDAI ⩾ 4) with inadequate response to ⩾1 NSAID | Adalimumab SC 40 mg every other week |

Adalimumab: n = 22 Placebo: n = 24 |

Primary: ASAS40 response at week 12. Key secondary: ASAS20, ASAS partial remission, improvement of disease activity measures, physical function, spinal mobility, and health related QoL at week 12 |

ASAS20: 68.2% versus 25% ASAS40: 54.5% versus 12.5% ASAS partial remission: 22.7% versus 0% for adalimumab versus placebo at week 12 |

23 |

| ABILITY-1 | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled | 12 weeks double blind + open-label extension up to week 114 |

Active nr-axSpA (BASDAI ⩾ 4 and total back pain ⩾ 4 by VAS 0–10 cm) with inadequate response to ⩾1 NSAID | Adalimumab SC 40 mg every other week |

Adalimumab: n = 91 Placebo: n = 94 |

Primary: ASAS40 response at week 12 Key secondary: ASAS20, ASAS5/6, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS inactive disease, improvement of disease activity measures, physical function, spinal mobility, and health-related QoL, as well as active inflammation in the spine and sacroiliac joints on MRI |

ASAS20: 52% versus 31% ASAS40: 36% versus 15% ASAS partial remission: 16% versus 5% ASDAS inactive disease: 24% versus 4% for adalimumab versus placebo at week 12 |

18 |

| RAPID-axSpA | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled | 24 weeks double blind + dose blind to week 48 + open label up to week 204 |

Active axSpA (BASDAI ⩾ 4 and total back pain ⩾ 4 by VAS 0–10 cm, elevated CRP and/or sacroiliitis on MRI) with inadequate response to ⩾1 NSAID | Certolizumab pegol SC 400 mg every 4 weeks or certolizumab pegol SC 200 mg every 2 weeks |

Certolizumab pegol 400 mg: n = 107 Certolizumab pegol 200 mg: n = 111 Placebo: n = 107 Nr-axSpA: 147 patients out of 325 |

Primary: ASAS20 at week 12 Key secondary: ASAS40, ASAS partial remission, BASDAI50, ASDAS responses, improvement of disease activity measures, physical function, spinal mobility, and health-related QoL, as well as active inflammation in the spine and sacroiliac joints on MRI |

ASAS20: 62.7% and 58.7% versus 40.0% ASAS40: 47.1% and 47.8% versus 16.0% for certolizumab pegol 400 mg every 4 weeks versus 200 mg every 2 weeks versus placebo at week 12 in the nr-axSpA subgroup |

17 |

| ESTHER | Randomized, open label, controlled | 48 weeks open label + open-label extension for up to year 10 |

Active axSpA (BASDAI ⩾ 4 and total back pain ⩾ 4 by VAS 0–10 cm, active inflammation on MRI either in the sacroiliac joints or in the spine) with inadequate response to ⩾1 NSAID Symptom duration < 5 years |

Etanercept SC 25 mg twice weekly versus sulfasalazine 2–3 g/d orally |

Etanercept: n = 40 (n = 20 with nr-axSpA) Sulfasalazine: n = 36 (n = 17 with nr-axSpA) |

Primary: change of active inflammatory lesions in the sacroiliac joints and spine detected by MRI at week 48 Key secondary: ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS partial remission, and ASDAS inactive disease |

ASAS20: 85% ASAS40: 65% ASAS partial remission: 60% ASDAS inactive disease: 40% for etanercept at week 48 in the nr-axSpA subgroup |

27 |

| EMBARK | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled | 12 weeks double blind + open-label extension up to week 92 |

Active nr-axSpA (BASDAI ⩾ 4) with inadequate response to ⩾1 NSAID Age: 18–49-years old Symptom duration < 5 years |

Etanercept SC 50 mg once a week |

Etanercept: n = 102 Placebo: n = 106 |

Primary: ASAS40 at week 12 Key secondary: ASAS20, ASDAS inactive disease, improvement of disease activity measures, physical function, spinal mobility, and health-related QoL, as well as active inflammation in the spine and sacroiliac joints on MRI |

ASAS20: 52% versus 36% ASAS40: 32% versus 16% ASDAS inactive disease: 40% versus 17% for etanercept versus placebo at week 12 |

19 |

| GO-AHEAD | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled | 16 weeks double blind + open-label extension up to week 60 |

Active nr-axSpA (BASDAI ⩾ 4 and total back pain ⩾ 4 by VAS 0–10 cm) with inadequate response to ⩾1 NSAID Symptom duration ⩽ 5 years |

Golimumab SC 50 mg every 4 weeks | Golimumab: n = 97 Placebo: n = 100 |

Primary: ASAS20 at week 16 Key secondary: ASAS40, ASAS partial remission, improvement of disease activity measures, physical function, spinal mobility and health-related QoL, as well as active inflammation in the spine and sacroiliac joints on MRI |

ASAS20: 71% versus 40% ASAS40: 57% versus 23% ASAS partial remission 33% versus 18% for golimumab versus placebo at week 16 |

20 |

AxSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; ASAS, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society; ASDAS, ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score; BASDAI, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; nr-axSpA, nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; QoL, quality of life; VAS, visual analogue scale; SC, subcutaneous.

Based on the data from phase III trials in nr-axSpA, the EMA included presence of objective signs of inflammatory activity, either active inflammation on MRI or elevated CRP, as an obligatory condition for initiation of anti-TNFα therapy in patients with nr-axSpA, in addition to high clinical disease activity and failure of previous therapy. The use of TNFα inhibitors for the treatment of nr-axSpA in the US is not yet approved, reflecting the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) concerns about the natural course of nr-axSpA and the specificity of the ASAS criteria.21 The FDA recognized in its document of ‘Arthritis Advisory Committee Meeting 22 July, 2013’ (see the meeting minutes here: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/ArthritisAdvisoryCommittee/UCM367285.pdf) the possibility of the presence of inflammation in sacroiliac joints without radiographic sacroiliitis, that is, the existence of nr-axSpA. Nevertheless, the FDA requests clinical development programs for the use of biological drugs in patients fulfilling the ASAS axSpA criteria to dissipate its concerns about the heterogeneity of population that could be included in ASAS criteria and to ensure the risk–benefit profile remains favorable for the indicated population.

The only IL-17 inhibitor currently available on the market (secukinumab) is approved for the treatment of AS in the US, EU and many other countries based on the favorable results of the phase III program.22 The phase III study for the indication nr-axSpA is currently in progress [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02696031].

Evidence for the efficacy of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors in nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis

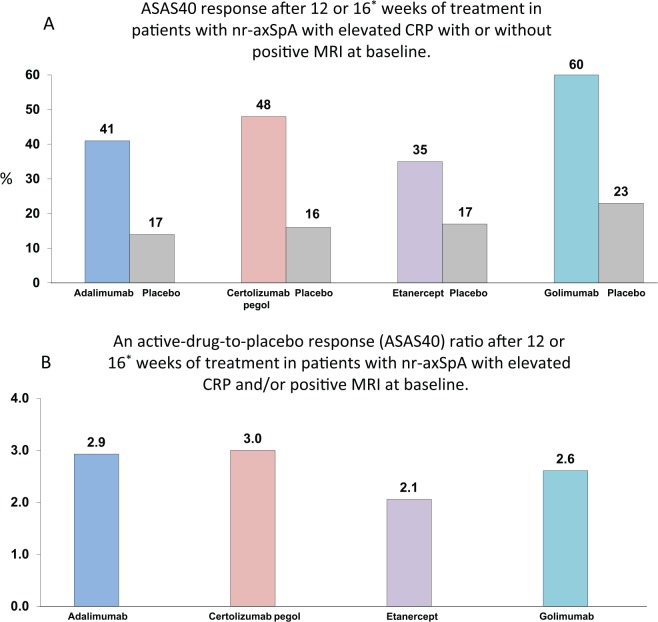

The approval of four TNFα inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab) for the treatment of nr-axSpA was a result of successful phase III studies and some preceding studies conducted as investigator-initiated trials, the main results of which are summarized in Table 2. Importantly, all these phase III trials had slightly different inclusion criteria (Table 2) that resulted in a substantial variation in the response rates across the studies. Even in the target population (nr-axSpA with objective signs of inflammation, either elevated CRP or inflammation on MRI), some heterogeneity of responses is evident (Figure 1A) that could be attributed also to factors beyond the inclusion criteria (e.g. to geographic differences). Nonetheless, analyzing the active drug to placebo response ratio, we see a higher homogeneity of the results as shown in Figure 1B. In the following, we present the available data for the single drugs approved for nr-axSpA in more details.

Figure 1.

ASAS40 response rates to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (A) and active-drug-to-placebo response ratio (B) in the target population (with elevated CRP and/or positive MRI at baseline) of patients with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis from the placebo-controlled phases of the phase III trials.

*Week 12 for adalimumab, etanercept, and certolizumab pegol (200 mg every 2 weeks), week 16 for golimumab.

Different studies, no head-to-head comparisons.

AxSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; ASAS, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society; CRP, C-reactive protein; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; nr-axSpA, nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Adalimumab

Adalimumab was the first TNFα inhibitor authorized by EMA in 2012 for use in Europe for patients with a nr-axSpA without an adequate response to NSAIDs, limited to those who show evidence of inflammation by elevated CRP and/or positive MRI. In 2008, Haibel et al. reported results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of patients with an active axSpA without definite radiographic sacroiliitis who received adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneously (SC) every 2 weeks versus placebo up to week 12, followed by an open-label period of 48 weeks. At week 12, the ASAS40 response was achieved by 54.5% of the patients in the adalimumab group versus 12.5% in the placebo group (p = 0.004); the efficacy was maintained in all patients until week 52.23 Similar results were found in the ABILITY-1 study, a randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study for the indication of nr-axSpA, in which n = 185 patients with active nr-axSpA (according to the ASAS classification criteria) were randomized 1:1 to be treated with adalimumab 40 mg SC every 2 weeks versus placebo for 12 weeks, followed by an open-label extension up to week 114. Significantly more patients in the adalimumab group achieved the primary endpoint, ASAS40 response at week 12, compared with the placebo group (36% versus 15%, p < 0.001), Table 2.18 Recent data show that achievement of remission (i.e. ASDAS inactive disease, ASDAS <1.3) was associated with a clinically meaningful improvement in physical function, health-related quality of life and work productivity of those patients.24 In this study, no restrictions in terms of symptom duration or objective signs of inflammation were applied. In the post hoc analysis, it became evident, that there was a significant difference in response rates to adalimumab versus placebo only in patients with objective signs of inflammation (elevated CRP and/or active inflammation on MRI of the sacroiliac joints), Figure 1. This led to the approval of adalimumab as the first TNFα inhibitor for patients with active nr-axSpA demonstrating objective signs of inflammatory activity as defined above (target population).

Certolizumab pegol

Certolizumab pegol (CZP) has been evaluated in the RAPID-axSpA clinical trial for the treatment of all active axSpA patients. This phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 325 patients with axSpA (n = 178 with AS and n = 147 with nr-axSpA) to be treated with CZP SC 400 mg every 4 weeks versus 200 mg every 2 weeks versus placebo for a period of 24 weeks, followed by a dose-blinded phase up to week 48 and then an open-label extension until week 204. All included patients had to fulfill the ASAS criteria for axSpA and were required to have an objective sign of inflammatory activity: elevated CRP and/or osteitis on MRI of sacroiliac joints. There were no restrictions in terms of symptom duration of axSpA. The primary endpoint, ASAS20 response at week 12, was achieved by 57.7% and 63.6% in the CZP 400mg Q4W and CZP 200 mg Q2W, respectively, versus 38.3% in the placebo group for the entire axSpA population (differences to placebo were statistically significant). Analyzed by subgroups (AS versus nr-axSpA), both groups had a similar response to CZP with a slightly better response tendency in the nr-axSpA, particularly in the CZP 200mg Q2W group with ASAS20 58.7%, ASAS40 47.8% and ASAS partial remission 28.3% versus ASAS20 56.9%, ASAS40 40.0% and ASAS partial remission 20.0% in the AS group. Similar results were obtained from week 24, with moderately higher responses than at week 12, without clear differences between the two subgroups.25 These data indicate that given a similar level of inflammatory activity (level of CRP, inflammation of MRI), a similar response to anti-TNFα therapy in nonradiographic and radiographic forms of axSpA can be expected.

In September 2013, EMA approved the use of CZP for the treatment of EU patients with nr-axSpA, elevated CRP and/or positive MRI, after showing a poor response to NSAIDs.

Etanercept

Although etanercept was the first TNFα inhibitor investigated for the treatment of patients with nr-axSpA in 2004, in that time called undifferentiated SpA, in a small open-label study by Brandt et al.,26 and later on in the ESTHER study, it was authorized by the EMA for the use in nr-axSpA only in June 2014, after completion of a phase III trial (EMBARK).

The ESTHER study included patients with active axSpA (AS and nr-axSpA) with symptom duration < 5 years and presence of active inflammation in the axial skeleton on MRI. Patients were randomized for treatment with either etanercept 50 mg SC weekly or sulfasalazine for 1 year. At year 1, patients from both groups who were not in remission continued with etanercept in a long-term open-label extension; patients who were in remission dropped their medication and were followed up for 1 year, and, in case of flare, etanercept was (re)-introduced and continued in a long-term extension. The efficacy and safety data analyzed by both subgroups (AS and nr-axSpA) brought similar results, suggesting that clinical response to etanercept is the same in nr-axSpA and AS (i.e. ASAS inactive disease was achieved by 40% of the patients treated with etanercept in both axSpA subgroups), given the same level of inflammatory activity at baseline.27,28 Remarkably, this similar level of response remained also in the long-term extension up to year 4, indicating a similar course of the disease in nonradiographic and radiographic forms of axSpA.29

Most recently, results of a 48-week period from the EMBARK study, a phase III study with etanercept in nr-axSpA, have been reported (Table 2, Figure 1). This clinical trial recruited patients with nr-axSpA according to the ASAS criteria with symptom duration up to 5 years. There were no restrictions in terms of objective signs of inflammatory activity. Included patients were randomized for treatment with etanercept 50 mg SC once a week versus placebo for a 12-week double-blind period, followed by an open-label extension of 92 weeks in which all patients received etanercept. From the 215 patients included in the study, 32% of the etanercept arm compared with 16% of the placebo one achieved ASAS40 response at week 12, the primary study endpoint. Objective signs of inflammation (elevated CRP and/or bone marrow edema on MRI of sacroiliac joints) showed a clear association with a better clinical response to etanercept.30 Treatment of etanercept was associated with reduction of active inflammation in the axial skeleton on MRI in the ESTHER28 and in the EMBARK studies.19

Data from the ESTHER and EMBARK trials were the basis for the approval of etanercept in June 2014 for the treatment of active nr-axSpA in the EU, and subsequently, many other countries around the world.

Golimumab

Efficacy of golimumab in nr-axSpA was recently investigated in the phase III trial GO-AHEAD. In this double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study, patients with nr-axSpA and symptom duration up to 5 years were treated with golimumab 50 mg SC every 4 weeks versus placebo up to week 16 with an open-label extension until week 60. Again, there were no restrictions regarding objective signs of inflammation in this trial. The first results after 16 weeks of treatment were recently published (Table 2, Figure 1). From the 198 patients included in the study, 71.1% and 40.0% of patients treated with golimumab and placebo, respectively (p < 0.001) achieved the primary endpoint – the ASAS20 response at week 16. Similar to previous reports, presence of objective signs of inflammation was clearly associated with a better response to golimumab. In patients with a negative MRI and normal levels of CRP at baseline there was no difference in the response rate between golimumab and placebo treatment. By contrast, patients with inflammation by MRI and/or elevated CRP at baseline, showed a significantly better treatment response to golimumab than to placebo (Figure 1).20

Golimumab was approved in Europe by EMA in June 2015 for treating patients with nr-axSpA who have an inadequate response to NSAIDs and present elevated CRP and/or signs of inflammation by MRI.

Personalizing therapy with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

All TNFα inhibitors except infliximab are approved for the use in nr-axSpA in Europe and many other countries, but not in the US. They seem to have similar efficacy in axial symptoms; however, their efficacy might differ with regard to extra-articular manifestations. Following ASAS/EULAR recommendations updated in 2016,8 anti-TNFα monoclonal antibodies (infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab), and to some extent also the Fab fragment of a monoclonal antibody certolizumab pegol, are preferred in patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease or recurrent uveitis rather than etanercept. The data related to etanercept for the treatment of uveitis are inconclusive and there are several case reports describing Crohn’s disease onset in patients with AS who started etanercept therapy.31,32

For those patients with nr-axSpA who have a lack of efficacy or intolerance to the first TNFα inhibitor, the ASAS/EULAR recommendations advise a change to a second TNFα inhibitor or a change of the drug class.8 Although there are no specific data on the efficacy of TNFα inhibitors switching in nr-axSpA, the results of the previous studies with positive outcomes in AS33–35 and axSpA36 could be extrapolated to the nr-axSpA group. Moreover, to date, there is no biological treatment alternative to TNFα inhibitors for nr-axSpA. In contrast with AS, there is no approval yet for anti-IL-17 for the treatment of nr-axSpA patients. Data from large Scandinavian registries (DANBIO and ARTIS) confirmed that switching to a second TNFα inhibitor could be effective in AS patients.37,38 In addition, in the ARTIS, there was a significantly longer drug survival period in patients with AS who were receiving conventional DMARDs (sulfasalazine or methotrexate in the majority of patients) as comedication.39 Similar observation regarding a conventional DMARD comedication was also made in the Swiss Clinical Quality Management cohort.40 In contrast, these results were not confirmed in the Rheumatic Diseases Portuguese Register, where comedication with conventional DMARDs had no impact on the anti-TNFα retention.41 Overall, available data do not justify a routine co-administration of conventional DMARDs with TNFα inhibitors in axSpA.

Zurfferey et al. did not see statistically significant differences in the anti-TNFα drug survival with regards to the classification of patients as nr-axSpA or AS42 in a monocenter study. Similar data were obtained in a larger multicenter Swiss cohort.43 Specifically for nr-axSpA, a Swedish cohort observed a favorable treatment course with an estimated 76% drug survival after the first year of treatment and 65% after the second year. In this cohort, positive predictive factors for a good drug survival were presence of inflammation in the MRI at baseline and male gender.44 Overall, these data indicate that in nr-axSpA, a similar response to and survival of TNFα inhibitors, as is known for AS, can be expected.

Despite the great benefit that anti-TNFα therapy has brought to many patients with SpA, the high cost of these drugs is causing a substantial impact on national health economies. Therefore, in the recent years, the treatment guidelines were trying to optimize the use of anti-TNFα agents. The ASAS/EULAR recommendations of 2016 suggest the possibility of tapering the TNFα inhibitors once the patient has achieved sustained remission.8 The cost-effectiveness of anti-TNFα medications in SpA is still controversial. The existing studies have focused on the disease progression in functional limitations and symptoms without considering the possible impact on ability to work that this treatment may have, such as reducing the risk of permanent work disability or sick days, decreasing the overall socioeconomic costs.45 Other factors that might influence the cost effectiveness of TNFα inhibitors are the administration costs, the rebound assumption on patients after stopping the therapy and the long-term effect anti-TNFα therapy has on structural damage progression and therefore, on the physical function.46 Considering all these parameters would help the institutional policy decisions and in designing better schemes and more cost-effective guidelines for the treatment of SpA.

Safety of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors in nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis

The data available on safety of TNFα-inhibitors in patients with nr-axSpA are limited, however the results of the studies performed for those patients are similar to results observed in AS patients, without detecting new safety signals. All anti-TNFα agents are shown to be well tolerated and consistently safe in axSpA in short- and long-term treatment. The data reported from registers and clinical trials with their extensions suggest that there is no association between the treatment with TNFα-inhibitor and an increase in mortality or in the incidence of malignancies, including lymphoma (except skin malignancies), compared with the general population or with patients receiving therapy with conventional DMARDs. Most of the data collected for safety come from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and AS, as their treatment with TNFα-inhibitors have been available for almost 20 years.47–51 Nevertheless, the risk of serious infection in patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy is significantly higher, specifically during the first 6 months of treatment.52

It is recommended for all patients with axSpA including nr-axSpA who begin a therapy with an anti-TNFα agent to apply standard precautions relating to infections, malignancies and demyelinating diseases. Screening for tuberculosis infection before starting the TNFα-inhibitor is required due to the risk of reactivating a latent tuberculosis infection. Most countries recommend including a full medical history, physical examination, thorax X-ray and tuberculin skin test or interferon-gamma release assay in the screening process. Patients with a positive result for a latent tuberculosis infection should receive a prophylactic treatment to prevent its reactivation. The necessary duration of tuberculostatic treatment before starting the TNFα-inhibitor is not clear, but most recommendations suggest administering at least 1 month of the tuberculostatic treatment prior to beginning the TNFα-inhibitor.

The formation of antidrug antibodies (ADAb), in this case, antibodies against TNFα agents, has been associated in different studies with a reduced clinical response and an increased incidence of hypersensitivity reaction. The lack of clinical response observed in patients with ADAb may be explained by immune-complex formation between anti-TNFα agent and ADAb, suppressing the drug activity and thereby limiting its therapeutic action.53 The risk of developing ADAb varies with each type of TNFα inhibitor, most frequently observed in adalimumab and infliximab therapy.54,55 The effect that the antibodies can have on treatment response for axSpA remains unclear.56 It seems that etanercept would be less immunogenic than the other TNFα inhibitors.57

Future therapies

Although TNFα inhibitors have been a great advance in the treatment of axSpA, there remain 30–40% of patients who do not reach a good clinical response. So, there is an impetus to find other possible treatments for those patients. Most of the alternative therapies to TNFα inhibitor available for rheumatoid arthritis have been also tested in axSpA patients, but have not demonstrated good results. They have not been specifically tested for nr-axSpA but the results obtained from AS patients were unsatisfying. Rituximab did not show a sufficient response in patients with axSpA who previously failed to show substantial improvement with TNFα therapy, although there was some modest response in anti-TNFα-naïve patients.58 Similar negative results were demonstrated in several studies with abatacept, anakinra, tocilizumab and sarilumab.59–62 Apremilast (a phosphodiaestherase-4 inhibitor approved for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis) was not superior to placebo with respect to the primary endpoints (ASAS20 response at week 16) in a phase III trial in AS [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01583374].

Currently, it has been suggested that IL-17 might be an essential mediator of inflammation in axSpA. Secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against IL-17A, was approved in 2015 for the treatment of AS supported by the data of the MEASURE 1 and MEASURE 2 clinical trials.22 Anti-IL-17 agents, such as secukinumab and ixekizumab, are currently being tested for their efficacy in patients with nr-axSpA [ClinicalTrial.gov identifiers: NCT02696031 and NCT02757352].

Another potentially effective drug in axSpA interfering with the Th17 axis by blocking IL-23 is ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody against p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, that is authorized for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. In axSpA, the data from a proof-of-concept trial with ustekinumab in patients with active AS are encouraging.63 Currently, there are several phase III clinical trials in axSpA, and one ongoing study specifically for nr-axSpA [ClinicalTrial.gov identifier: NCT02407223].

Conclusion

In recent years, TNFα-inhibitors have been extensively investigated in phase III programs in nr-axSpA. There have been no head-to-head trials comparing TNFα-inhibitors in nr-axSpA (or in AS). An indirect comparison based on the results of phase III trials is difficult, due to different inclusion/exclusion criteria, the presence of objective signs of inflammation (required to be present in the certolizumab pegol study), and, in particular, study duration (no restrictions in terms of study duration in the adalimumab and golimumab trials).

However, it is evident that TNFα inhibitors are significantly more effective than placebo only in the ‘target population’, nr-axSpA patients with objective signs of inflammation (positive CRP and/or osteitis in the sacroiliac joints/spine on MRI). Therefore, the current indication for TNFα-inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab pegol and golimumab) in nr-axSpA requires not only clinically active disease not responding to the first-line therapy (usually with NSAIDs), but also the presence of the mentioned objective signs of inflammation. Nonetheless, even in patients representing the target population, the efficacy data still appear heterogeneous (Figure 1a), most likely due to factors beyond symptom duration and inflammatory activity. Presenting the data as a ratio of active-drug-to-placebo response yields more homogeneous results (Figure 1b). Importantly, patients with comparable levels of inflammatory activity demonstrate similar response to TNFα inhibitors irrespective of the presence or absence of radiographic sacroiliitis. There were no new safety signals in any of the studies for nr-axSpA. Long-term studies (up to 10 years) are underway now, as well as registries.

Currently, a number of new drugs mostly targeting the Th17 pathway are under investigation in both radiographic and nonradiographic axial SpA.

Despite major advances, several challenges in the treatment of nr-axSpA remain:

Only a small proportion of patients achieve the primary treatment target,64 remission. Early recognition and early and tightly controlled treatment might improve the outcome; however, this should be demonstrated in respective trials.

There are only limited data about the possibility of discontinuation of TNFα inhibitors upon achievement of remission in nr-axSpA. Previous studies suggest that discontinuing treatment leads to relapse/loss of remission in 60–80% of patients after stopping the therapy for up to 1 year.65–67 Currently, a number of trials investigate strategies for treatment discontinuation versus dose tapering versus continuous treatment with TNFα inhibitors after achieving remission in nr-axSpA [ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT01808118, NCT02505542 and NTC02509026].

Finally, the potential prevention of structural damage development in the sacroiliac joints and spine by treating patients at the nonradiographic stage is of high interest and relevance for the long-term outcome. It needs to be proven in clinical trials if early and effective anti-inflammatory treatment might indeed prevent structural damage development in the axial skeleton, as suggested in observational studies.68,69

In summary, availability of TNFα inhibitors for the treatment of patients with nr-axSpA certainly contributes to the improving of the short- and long-term outcomes in this disease by broadening the spectrum of possibilities for those who do not respond to first-line treatments. In the near future, we will certainly see a further increase in the number of therapeutic options in axSpA, including nr-axSpA, that would require development of optimized and ideally individualized treatment strategies to reach and maintain the remission status.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: VR: none declared; DP: received grant/research support from AbbVie, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer; consultant for: AbbVie, BMS, Boehringer, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; speakers bureau: AbbVie, BMS, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB.

Contributor Information

Valeria Rios Rodriguez, Department of Gastroenterology, Infectiology and Rheumatology, Campus Benjamin Franklin, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

Denis Poddubnyy, Department of Gastroenterology, Infectiology and Rheumatology, Campus Benjamin Franklin, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Hindenburgdamm 30, 12203 Berlin, Germany.

References

- 1. Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet. Epub ahead of print 19 January 2017. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Landewe R, Dougados M, Mielants H, et al. Physical function in ankylosing spondylitis is independently determined by both disease activity and radiographic damage of the spine. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984; 27: 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rudwaleit M, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, et al. The early disease stage in axial spondylarthritis: results from the german spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poddubnyy D, Haibel H, Braun J, et al. Brief report: clinical course over two years in patients with early nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis and patients with ankylosing spondylitis not treated with tumor necrosis factor blockers: results from the German Spondyloarthritis Inception Cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67: 2369–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kiltz U, Baraliakos X, Karakostas P, et al. Do patients with non-radiographic axial spondylarthritis differ from patients with ankylosing spondylitis? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64: 1415–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewe R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. Epub ahead of print 13 January 2017. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haibel H, Brandt HC, Song IH, et al. No efficacy of subcutaneous methotrexate in active ankylosing spondylitis: a 16-week open-label trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66: 419–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Braun J, et al. Six months open label trial of leflunomide in active ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 124–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Braun J, Zochling J, Baraliakos X, et al. Efficacy of sulfasalazine in patients with inflammatory back pain due to undifferentiated spondyloarthritis and early ankylosing spondylitis: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65: 1147–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, et al. American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network 2015 Recommendations for the Treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68: 282–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davis JC, van der Heijde DM, Braun J, et al. Sustained durability and tolerability of etanercept in ankylosing spondylitis for 96 weeks. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 1557–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 582–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 2136–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Inman RD, Davis JC, Jr, Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 3402–3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landewe R, Braun J, Deodhar A, et al. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis: 24-week results of a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results of a randomised placebo-controlled trial (ABILITY-1). Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72:815–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maksymowych WP, Dougados M, van der Heijde D, et al. Clinical and MRI responses to etanercept in early non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: 48-week results from the EMBARK study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 1328–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 16-week study of subcutaneous golimumab in patients with active non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67: 2702–2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deodhar A, Reveille JD, van den Bosch F, et al. The concept of axial spondyloarthritis: joint statement of the spondyloarthritis research and treatment network and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society in response to the US Food and Drug Administration’s comments and concerns. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: 2649–2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2534–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Listing J, et al. Efficacy of adalimumab in the treatment of axial spondylarthritis without radiographically defined sacroiliitis: results of a twelve-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial followed by an open-label extension up to week fifty-two. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 1981–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van der Heijde D, Joshi A, Pangan AL, et al. ASAS40 and ASDAS clinical responses in the ABILITY-1 clinical trial translate to meaningful improvements in physical function, health-related quality of life and work productivity in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016; 55: 80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sieper J, Landewe R, Rudwaleit M, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol over ninety-six weeks in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from a phase III randomized trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67: 668–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brandt J, Khariouzov A, Listing J, et al. Successful short term treatment of patients with severe undifferentiated spondyloarthritis with the anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha fusion receptor protein etanercept. J Rheumatol 2004; 31: 531–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song IH, Hermann K, Haibel H, et al. Effects of etanercept versus sulfasalazine in early axial spondyloarthritis on active inflammatory lesions as detected by whole-body MRI (ESTHER): a 48-week randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 590–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Song IH, Weiss A, Hermann KG, et al. Similar response rates in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis after 1 year of treatment with etanercept: results from the ESTHER trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 823–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Song IH, Hermann KG, Haibel H, et al. Consistently good clinical response in patients with early axial spondyloarthritis after 3 years of continuous treatment with etanercept: longterm data of the ESTHER trial. J Rheumatol 2014; 41: 2034–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, et al. Symptomatic efficacy of etanercept and its effects on objective signs of inflammation in early nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: 2091–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, O’Connor P, et al. Efficacy of etanercept for treatment of Crohn’s related spondyloarthritis but not colitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62: 74–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mrabet D, Selmi A, Filali A, et al. Onset of Crohn’s disease induced by etanercept therapy: a case report. Rev Med Liege 2012; 67:619–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coates LC, Cawkwell LS, Ng NW, et al. Real life experience confirms sustained response to long-term biologics and switching in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47: 897–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pradeep DJ, Keat AC, Gaffney K, et al. Switching anti-TNF therapy in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology 2008; 47: 1726–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lie E, van der Heijde D, Uhlig T, et al. Effectiveness of switching between TNF inhibitors in ankylosing spondylitis: data from the NOR-DMARD register. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dadoun S, Geri G, Paternotte S, et al. Switching between tumour necrosis factor blockers in spondyloarthritis: a retrospective monocentre study of 222 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011; 29: 1010–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lie E, van der Heijde D, Uhlig T, et al. Effectiveness of switching between TNF inhibitors in ankylosing spondylitis: data from the NOR-DMARD register. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Krogh NS, et al. Clinical response, drug survival and predictors thereof in 432 ankylosing spondylitis patients after switching tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitor therapy: results from the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 1149–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lie E, Kristensen LE, Forsblad-d’Elia H, et al. The effect of comedication with conventional synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs on TNF inhibitor drug survival in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis: results from a nationwide prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 970–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nissen MJ, Ciurea A, Bernhard J, et al. The effect of comedication with a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug on drug retention and clinical effectiveness of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68: 2141–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sepriano A, Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, et al. Effect of comedication with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs on retention of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in patients with spondyloarthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68: 2671–2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zufferey P, Ghosn J, Becce F, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor drug survival in axial spondyloarthritis is independent of the classification criteria. Rheumatol Int 2015; 35: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ciurea A, Scherer A, Exer P, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition in radiographic and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results from a large observational cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65: 3096–3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gulfe A, Kapetanovic MC, Kristensen LE. Efficacy and drug survival of anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapies in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: an observational cohort study from Southern Sweden. Scand J Rheumatol 2014; 43: 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reveille JD, Ximenes A, Ward MM. Economic considerations of the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Am J Med Sci 2012; 343: 371–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Corbett M, Soares M, Jhuti G, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2016; 20: 1–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Davis JC, Jr, van der Heijde DM, Braun J, et al. Efficacy and safety of up to 192 weeks of etanercept therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lunt M, Watson KD, Dixon WG, et al. No evidence of association between anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62: 3145–3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Askling J, Baecklund E, Granath F, et al. Anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and risk of malignant lymphomas: relative risks and time trends in the Swedish Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 648–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Strangfeld A, Hierse F, Rau R, et al. Risk of incident or recurrent malignancies among patients with rheumatoid arthritis exposed to biologic therapy in the German biologics register RABBIT. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12: R5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kay J, Fleischmann R, Keystone E, et al. Golimumab 3-year safety update: an analysis of pooled data from the long-term extensions of randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials conducted in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 538–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Galloway JB, Hyrich KL, Mercer LK, et al. Anti-TNF therapy is associated with an increased risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis especially in the first 6 months of treatment: updated results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register with special emphasis on risks in the elderly. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011; 50: 124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vincent FB, Morand EF, Murphy K, et al. Antidrug antibodies (ADAb) to tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-specific neutralising agents in chronic inflammatory diseases: a real issue, a clinical perspective. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maneiro JR, Salgado E, Gomez-Reino JJ. Immunogenicity of monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrosis factor used in chronic immune-mediated Inflammatory conditions: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 1416–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Thomas SS, Borazan N, Barroso N, et al. Comparative immunogenicity of TNF inhibitors: impact on clinical efficacy and tolerability in the management of autoimmune diseases. A systematic review and meta-analysis. BioDrugs 2015; 29: 241–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Braun J, Deodhar A, Inman RD, et al. Golimumab administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks in ankylosing spondylitis: 104-week results of the GO-RAISE study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71: 661–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. De Vries MK, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Immunogenicity does not influence treatment with etanercept in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Song IH, Heldmann F, Rudwaleit M, et al. Different response to rituximab in tumor necrosis factor blocker-naive patients with active ankylosing spondylitis and in patients in whom tumor necrosis factor blockers have failed: a twenty-four-week clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62: 1290–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Listing J, et al. Open label trial of anakinra in active ankylosing spondylitis over 24 weeks. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64: 296–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Song IH, Heldmann F, Rudwaleit M, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with abatacept: an open-label, 24-week pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 1108–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sieper J, Porter-Brown B, Thompson L, et al. Assessment of short-term symptomatic efficacy of tocilizumab in ankylosing spondylitis: results of randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sieper J, Braun J, Kay J, et al. Sarilumab for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: results of a phase II, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (ALIGN). Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 1051–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Poddubnyy D, Hermann KG, Callhoff J, et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results of a 28-week, prospective, open-label, proof-of-concept study (TOPAS). Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Smolen JS, Braun J, Dougados M, et al. Treating spondyloarthritis, including ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 6–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Song IH, Althoff CE, Haibel H, et al. Frequency and duration of drug-free remission after 1 year of treatment with etanercept versus sulfasalazine in early axial spondyloarthritis: 2 year data of the ESTHER trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71: 1212–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Haibel H, Heldmann F, Braun J, et al. Long-term efficacy of adalimumab after drug withdrawal and retreatment in patients with active non-radiographically evident axial spondyloarthritis who experience a flare. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65: 2211–2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sieper J, Lenaerts J, Wollenhaupt J, et al. Maintenance of biologic-free remission with naproxen or no treatment in patients with early, active axial spondyloarthritis: results from a 6-month, randomised, open-label follow-up study, INFAST Part 2. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Haroon N, Inman RD, Learch TJ, et al. The impact of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013; 65: 2645–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Maksymowych WP, Morency N, Conner-Spady B, et al. Suppression of inflammation and effects on new bone formation in ankylosing spondylitis: evidence for a window of opportunity in disease modification. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]