Abstract

Objectives:

To review comminuted patella fracture in the elderly patients and examine the surgical options to avoid complications such as fixation failure and poor functional outcome. To provide an example of mesh augmentation in comminuted patella fracture in the elderly patients.

Data Sources:

A literature review was conducted by the authors independently using Ovid, Medline, Cochrane, PubMed, and Clinical Key in English. We aimed to review data on patients older than 65 with comminuted patella fracture. Search conducted between July and December 2015.

Study Selection:

Search terms included patella fracture, elderly, and fixation failure. Abstracts were included if they were a case report, cohort series, or randomized control trial. Further inclusion criteria were that they were available in full text and included patient age(s), operative details, follow-up, and outcome discussion.

Data Extraction:

Each study was assessed according to its level of evidence, number of patients, age of patients, fracture patterns described, complications of treatment, and results summarized.

Data Synthesis:

Paucity of data and heterogeneity of studies limited statistical analysis. Data are presented as a review table with the key points summarized.

Conclusion:

In patella fracture, age >65 years and comminuted fracture pattern are predictors of increased fixation failure and postoperative stiffness, warranting special consideration. There is a trend toward improved functional outcomes when augmented fixation using mesh or plates is used in this group. Further level 1 studies are required to compare and validate new treatment options and compared them to standard surgical technique of tension band wire construct.

Keywords: patella, fracture, osteopenia, fixation failure, tension band wire, patella plating, patella mesh

Introduction

Patella fracture is a common problem, representing approximately 1% of all fractures.1 Displaced patella fractures or those which disrupt the extensor mechanism are usually managed operatively. The current standard remains a tension band wire (TBW) construct, with the option of additional cerclage wiring or TBW through cannulated screws.2 Elderly patients and particularly those with comminuted patella fracture are “difficult patella fractures” as their osteopenic bone often lacks the strength to support a TBW and/or cerclage, resulting in fixation failure prior to bone union. Partial or total patellectomy or nonoperative management is an option; however, it often results in poor functional outcomes.3 Recently, there has been a trend to plate or mesh-augmented fixation with good outcomes reported.4–6

We present the evidence on the management of “difficult patella fractures,” additionally, we describe a novel method of fixation, one easily implemented within any tertiary center. Our method describes the use of “X-change Revision Mesh” from Stryker as an adjunct to the TBW construct to reduce the incidence of cutout and failure.

Systematic Review Method

A literature review was conducted by the authors independently using Ovid, Medline, Cochrane, PubMed, and Clinical Key in English. Search terms included patella fracture, elderly, and fixation failure. Abstracts were included if they were a case report, cohort series, or randomized control trial. Further inclusion criteria were that they were available in full text and included patient age(s), operative details, follow-up, and outcome discussion. We aimed to review data on patients older than 65 with comminuted patella fracture. Search was conducted between July and December 2015.

Case Report

The patient is an 87-year-old, who incurred a closed right patella fracture, classified 34 C3 using the AO Muller classification.7 He was unable to straight leg raise, and the fracture showed significant displacement and comminution on X-ray (Figures 1 –3).

Figure 1.

Preoperative Anterior to Posterior (AP) X-ray.

Figure 2.

Preoperative lateral X-ray.

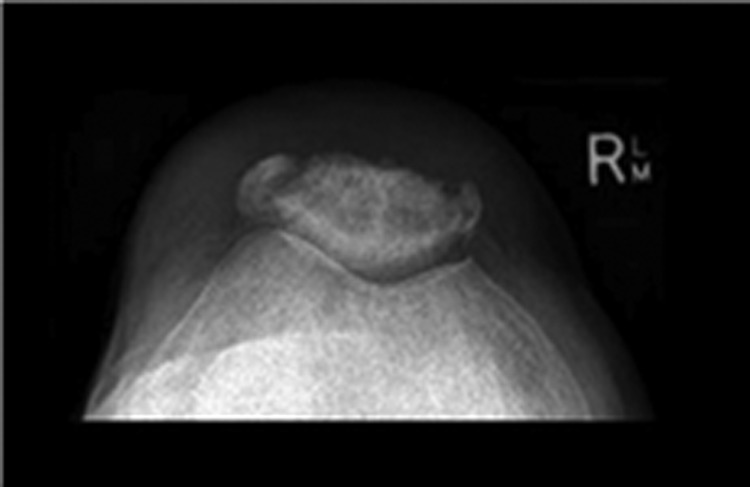

Figure 3.

Preoperative patella view.

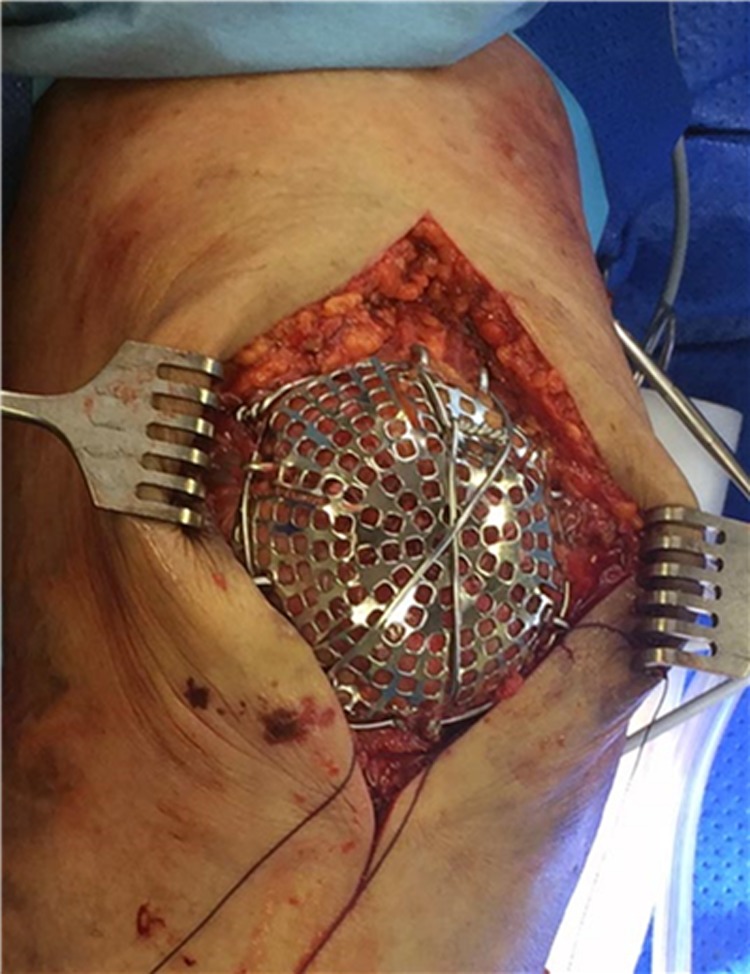

Under general anesthetic, the patient was positioned supine with a thigh tourniquet applied. A midline longitudinal incision was made over the patella, full thickness skin flaps were elevated. The fracture was exposed, and the fragments reduced using a tenaculum reduction clamp, with minimal detachment of the soft tissues. The reduction was assessed using fluoroscopy, the extensor retinaculum was repaired, and the “X-Change Acetabular Revision Mesh” was applied over the entire patella, this is an off-label use for this implant. The augmented tension band construct was formed using dual longitudinal and dual transverse K-wires passed through the mesh and a circumferential wire passed around the mesh. A figure of 8 cerclage tension band construct was completed by forming a 5 turn twist in the wire and bending the K-wires at both ends. The final reduction and fixation were checked using fluoroscopy. The wound was irrigated and closed in layers using knotless barbed sutures, and the skin closed using staples and an incisional vacuum dressing (Figures 4 –6).

Figure 4.

Anterior to Posterior (AP) X-ray taken 14 days postoperatively.

Figure 5.

Lateral X-ray taken 14 days postoperatively.

Figure 6.

Intraoperative photograph.

The patient discharged the following day in a hinged range of motion (ROM) brace set at 0° to 90° and allowed full weight bearing. At 2 weeks, his wound had healed and his ROM 10° to 45°. At 6 weeks, his ROM was 5° to 90° and could ambulate with the use of a single stick. At 6 months, his Lysholm knee score was 92. He had no complaint of metalware prominence (Figures 7 –10).

Figure 7.

Anterior to Posterior (AP) X-ray taken 42 days postoperatively.

Figure 8.

Lateral X-ray taken 42 days postoperatively.

Figure 9.

Postoperative clinical photographs standing Anterior to Posterior (AP), postoperative day 42.

Figure 10.

Postoperative clinical photograph supine, straight leg raise postoperative day 42.

Literature Review Results

One hundred twenty-three abstracts were reviewed, 22 articles were considered in full. A summary of the pertinent literature is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Literature.

| Authors | Year | n | Type of Evidence | Level | Aim | AO Fracture Classification | Method of Fixation | Findings | Average Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al | 1997 | 51 | Retrospective cohort series | 3 | Examined factors surrounding early failure of operative treatment of patella fracture | C1 x 51 (9 with comminution) | 38 TBW, Tensioned cable and K-wire in 11, TBW and cannulated screws x2 | 32 nonoperatively treated, TBW AO used in all but 3 cases, WBAT in extension brace, loss of reduction in 11 fractures, 9 patients required hardware removal, 4 complete failures due to patient noncompliance. 5 failures associated with technical aspects of the operation, that is, improper placement and not enough tension | 48 |

| Klassen | 1997 | 20 | Retrospective cohort series | 3 | Operative versus nonoperatively managed delayed union | B type 4, C1.1 7, C1.2 x 4, C1.3 2, C3 x 3 | TBW x 6, Bunnell wiring x 1, Cerclage x 1, Screw fixation x 1 | With nonunion average age 38, nonoperative in 7, and operative in 13, 1 persistent nonunion, operative management on nonunion increases functional outcome scores and can be expected to unite | 38 |

| Shabat et al | 2003 | 68 | Retrospective cohort study | 4 | Examined causality, compared operative versus nonoperative patella fracture in older patients | Surgical treatment better than nonsurgical | |||

| Shabat et al | 2004 | 14 | Retrospective case series | 4 | Outcomes of operatively managed primary patella fracture in elderly patients | Not Stated—10 conservative, 58 operative, and 45 comminuted | TBW | Operatively treated patella fracture with tension band wiring followed by cast immobilization for 6 weeks, all patients > 80 years age, average 83.3, all patients treated with ORIF and TBW. Severe limitation of range of motion noted requiring extensive physio, only 4 patients regained full extension | 83.3 |

| Kastelec and Veselko | 2004 | 28 | Retrospective cohort series | 3 | Compared distal pole resection with ORIF with mesh for distal pole fractures | C3.1 (excluded comminution) | Mesh versus PP | ORIF with Mesh had early ROM and weight bearing, better function outcomes and maintained patella ligament length. PP group had cast immobilization, worse functional outcome, and significantly shorter patella ligament | Avg 55 Range 11-77 |

| Huang et al | 2012 | 3 | Case series | 4 | Modified basket plate in inferior pole fractures | C1.3 x 3 | Mesh over inferior pole | Good clinical outcomes in all patients, metalware removed in 1 patient | 54, 87, and 89 |

| Eggink and Jaarsma | 2011 | 60 | Retrospective cohort series | 3 | Compared proximal bend TBW with distal and proximal bend TBW | C1 x 20, C2 x 9, C3 x 25, A1 x 6 | TBW | 60 total (40 followed up) 9 failures of fixation, 3 migration of K-wires, 6 insufficient tension, concluded that it is better to bend the K-wires proximally and distally | 44.9 |

| Dy et al | 2012 | 24 studies | Meta-analysis | 3 | Examined reoperation, nonunion and infection rates in patella fractures | 737 patella fractures | Not recorded | 737 patella fractures, reoperation common in 33.6%, age gender, operative technique, or date of publication did not influence the result | Not Specified |

| Lebrun16 | 2012 | 40 patients | Case series | 4 | Obtained patient reported outcome scores post patella fracture | C1 30%, C2 15%, C3 55% | TBW+Kwire 15, TBW through screws 10, longtidutinal anterior banding 2, PP 13 | 27 operated, 14 required hardware removal, study e-mailed questionnaires to patients then reviewed them | 46.3 |

| Miller et al | 2012 | 13 failures | Retrospective cohort series | 4 | Factors predicting failure of fixation | Type Ax1, Type Bx0 Type C x 12 | Screws and K-wires | 13 patients with failure of fixation examined, concluded that screws with wire is at least as good as TBW/K wire | 65 in failure group |

| Lazaro et al | 2013 | 30 | Retrospective case series | 4 | Outcomes of operatively managed primary patella fracture | C1.3 x 2 C2.1 x 2 C2.2 x 2 C2.3 x 2 C3.1 x 11 C3.2 x 11 | 12-month follow-up of 30 patella fractures, found significant functional impairment after surgery | 60.2 | |

| Taylor et al | 2014 | 8 | Case series | 4 | Plating of patella fractures techniques and outcomes | C3 x 6 | X-Plate 5 fractures, Mesh 2 | All patients healed without complication, 1 small undisplaced fragment in 1 patient | 47.4 |

| Hao et al | 2015 | 29 | Prospective case series | 4 | Outcomes claw fixation of patella fracture | C1 and C2 | Ti, Ni, SMA claw fixation memory alloy fixation | Ti, Ni, SMA claw fixation in 34-C1 and 34-C2 type fractures. Average age 43, Follow-up 11.48 months, No complications of management | 43 |

| Houdek et al | 2015 | 113 | Retrospective cohort study | 3 | Effects of previous patella fracture on TKA | Not specified | ORIF, PP, TP, and CM | Previous patella fracture leads to higher rates of MUA, limited ROM, and atherofibrosis. No increased revision rate | 67 |

| Kadar et al | 2015 | 188 | Retrospective case series | 4 | Predictors of nonunion, reoperation, and infection | A1 x 9 C1 x73, C1.2/1.3 x65 C3 x 33, Bx8 | Average follow-up 908 days, 6.9 (13p) infection, 1.6 (3p) nonunion, 42% required second operation, TBW more frequently associated with requiring a second operation. History of CVA increase risk of infection -old and nonunion 14-fold, Diabetics 8 × more likely to develop infection | 56 | |

| Bonnaig | 2014 | 52 | Retrospective cohort study | 3 | Compared partial patellectomy with ORIF | C1.1 x 19 C1.2 x 26 C3 x5 | Partial patellectomy or TBW with K-wires/Cannulated Screws | 26 patella plasty and 26 ORIF, no significant difference in the functional outcome scores for both groups, both did poorly | 43.8 PP and 44.8 ORIF |

| Lorich et al | 2015 | 9 | Retrospective case series | 4 | Mesh plating | 2 x 34 C1 7 x 34 C3 | Synthes 2.4 mm Mesh | Allowed full weight bearing, ROM allowed at 4 weeks. 2 × Contralateral DVT, Mean time to union of 23 weeks and all achieved union | Avg 65 Range 50 to 86 |

| Chen et al | 2013 | 25 | Matched cohort | 3 | Transosseous-braided suture | 14 x C1 2 x C2 9 x C3 | No.5 Ticron suture | Varied to surgeon preference, splinted for 0 to 6 weeks | 59.6 |

| RCT in Cochrane review | |||||||||

| Juutilainen17 | 1995 | 9 | RCT | 1 | See Cochrane review for full assessment | Prospective RCT, biodegradable versus metallic, polyglycolide acid screws and biodegradable wire. Excluded fractures with more than 3 fragments, all metallic implants removed after 1 year | |||

| Gunal18 | 1997 | 28 | RCT | 1 | See Cochrane review for full assessment | 12 patellectomy with advancement, 18 patelectomy, Mean age 28.3, All communited fractures. Follow-up mean 4.2 years. Nonvalidated scoring system | 28.3 | ||

| Chen19 | 1998 | 38 | RCT | 1 | See Cochrane review for full assessment | 2 years follow-up, RCT (used biopoly and biofix anchors, compared to metal. Severely comminuted fractures excluded). No grading of patella fracture, No difference found between the 2 groups | 46 | ||

| Luna-Pizzaro et al | 2006 | 53 | RCT | 1 | See Cochrane review for full assessment | 26 PCOS and 26 Standard. Excluded comminuted, fragmented, or osteoporotic patients by design. Less pain and better early results with PCOS Percutaneous fixation versus open, follow-up 2 years, Average age 47 (16-74), Used AO classification, only dealt with transverse and distal type fractures | 47 | ||

| Mao et al | 2013 | 39 | RCT | 1 | See Cochrane review for full assessment | Age 18 to 65 (Avg 41.8) Percutaneous fixation using cable pin system versus standard. 20 percutaneous, 19 open. Excluded comminuted fractures | 41.8 | ||

Abbreviations: AO, Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen; CM, Conservative management; DVT, Deep vein thrombosis; MUA, Manipulation under anesthesia; ORIF, open reduction internal fixation; PCOS, percutaneous osteosynthesis; PP, Partial patellectomy; RCT, randomized control trial; ROM, range of motion; TBW, tension band wire; TP, Total patellectomy; WBAT, Weight bear as tolerated.

Discussion

Patella Fracture Classification

We propose that a “difficult patella fracture” has the following characteristics.

Comminution—AO 34 A3 type, B3 type, and all C type fractures.

Age > 65 years.

Age and Comminution as a Predictor of Failure

With advancing age bone quality becomes a contributing factor in failure of fixation. Findings by Miller et al8 demonstrated factors predictive of failure of fixation. Age is a strong predictor of failure, the average age of patients who achieved successful fixation was 51 years compared to 65 years for those who had failure of fixation.8 Indirectly they found comminution a predictor of failure through the use of K-wires, they found that patients who require K-wire fixation of fragments were more likely to have comminuted fracture and this was an independent predictor of failure of fixation. Miller reported that 12 of the 13 patients who had failure of fixation had type C—patella fractures. Smith also identified age as a factor contributing to early failure in 2 of their patients aged 70.9

Management Aims

Treatment aims to return function to the extensor mechanism, reestablish patellofemoral joint congruency, and restore pain-free operation of the knee joint. Using TBW and delayed mobilization, many patients will have ongoing function deficit after patella fracture, which was well demonstrated in a paper by Lazaro et al10

There is little evidence in the literature to guide best management or even quantify the rate of which these complications can occur in the “difficult patella fracture patient”.

Management Options

Our literature review revealed very little evidence of superiority of any singly surgical technique when managing difficult patella fractures. It did however demonstrate a number of “practice pearls” applicable to all TBW constructs worth revising in point form:

TBW through cannulated screws is at least as good as tension band with K-wire8;

K-wires when used should be bent at both ends9;

double knot and minimum of 5 twists to the TBW11; and

percutaneous fixation produces better short to midterm results.12,13

A recent Cochrane review for the management of patella fractures in general found that:

biodegradable implants were no better than metallic implants for displaced patella fracture;

patellectomy with vastus medialis advancement is better than patellectomy alone; and

percutaneous fixation may give better results than traditional open methods.

The Cochrane review disregards the large body of data in the literature obtained through cohort series. All of the papers included in the Cochrane review excluded comminuted fractures from their studies; furthermore, the average ages of the patients in the group were very young, at 46. Systematic review of patella fracture management is available.

A meta-analysis by Dy et al14 of 24 studies reported that age, gender, open or closed fracture, operative technique, or date of publication did not significantly influence the reoperation, infection, or nonunion rate. Their meta-analysis found a 33.6% reoperation rate, an infection rate of 3.3%, and a nonunion rate of 1.3%.

They had not included fracture classification analysis due to the heterogeneity of reporting. Furthermore, the average age of all patients included in the studies equated to less than 60 years, with a majority being an average of less than 50 years of age.

The study by Kadar et al15 included a cohort of 188 patients and at 56 years had an older average age. They found a significant association between the history of cerebrovascular accident with rates of infection, nonunion, and a higher rate of second operation in diabetic patients.

Surgical Management of the Difficult Patella Fracture—Current Controversies and Future Considerations

Partial patellectomy is a controversial treatment option in the difficult patella fracture, with conflicting results reported in the literature. Bonnaig et al20 compared 26 patients treated with patella open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) with partial patellectomy. The average age of patients in this group was quite young; 43.8 years for the Partial Patellectomy (PP) group and 44.8 years for the ORIF group. The patients had predominantly transverse fractures in the ORIF group (65%) and inferior pole fractures in the PP group. Only 5 patients had multifragmentary fractures. They found no significant difference in the average Knee Outcome Score (KOS) Activities of Daily Living Score (ADLS) between the groups.

Contrary to Bonnaig’s results, Kastelec and Veselko found that patients undergoing PP compared with ORIF and basket plate for distal pole fractures did significantly worse in functional outcome scores, knee pain scores, and ROM. Additionally, PP patients were more likely to develop shortening of the patella ligament.4

Although TBW remains the most common method used, even when it is performed technically correctly, complications commonly occur.8,9

Stiffness

Stiffness may be an avoidable complication in patella fracture patients, especially those of older age through adequate fixation and early ROM. Shabat et al21 examined patella fracture in 14 patients aged >80 years. In his case series, all patients were managed operatively by TBW, then cast immobilized in 10° of flexion for 6 weeks. In long-term, only 4 patients regained full extension, all patients had an extension lag of 10° to 20° after cast removal, with a maximum flexion of 70°. Kastelec and Veselko also demonstrated inferior outcomes when patients were managed in cast immobilization, with significant decreases in function outcome and shortened patella ligaments.4 Although Shabat et al was advocated for immobilization to achieve union, followed by extensive physiotherapy, this clearly demonstrates the negative effects of immobilization on the function of the knee in elderly patients. Scarring and stiffness impact the function and reoperation rate for manipulation in future Total Knee Joint Replacement (TKJR) as demonstrated by Houdek et al.22

Avoiding Stiffness and Fixation Failure—A Trend Toward Plate and Mesh Fixation Emerging

There has been a trend toward the use of basket plate or mesh augmentation between 2000 and 2015 with a number of case reports published. Huang et al described a case series of 3 patients with inferior pole patella fractures fixed with a basket plate with screws and augmented with a cerclage wire.23

The patients had achieved union and had good ROM at the end of the follow-up period. The implants were removed after union in 1 patient. Both Matejcić et al24 and Kastelec and Veselko demonstrated superior results when distal pole fractures were managed operatively with basket plate osteosynthesis (BPO), compared to partial patellectomy.4

Matejcić et al24 presented a larger series comparing BPO and PP. Seventy-one patients underwent BPO and 49 patients underwent PP. Patients who underwent BPO were mobilized immediately with passive ROM exercises in the first week and active ranging from the third week. PP cohort patients were immobilized for 5 to 7 weeks, allowing partial weight bearing. A significantly better outcome was demonstrated in the BPO group using the Cincinnati knee rating test. In the studies by Matejcić et al and Kastelec and Veselko, both the surgical method and the rehabilitation protocol were different between the groups, making it difficult to determine which factor most contributed to the improved functional outcome.

In 2014, Taylor et al6 described 6 OA 34-C3 type fractures and 2 symptomatic nonunions of 34-C1 fractures with an average age of 47.4 years. They used lag screw fixation in most (7 of 8) cases, X-plate in 5 fractures, and mesh in 2 fractures. The mean follow-up was 13.6 months, with no cases of nonunion, infection or fixation failure, and an average ROM of 129°.

A most recent publication by Lorich et al5 described mesh augmentation in 9 patients, using 2.4 mm mesh. The allowed full weight bearing in extension and allowed ROM to commence at 4 weeks. They reported excellent union rates and mean time of union of 23 months in an older cohort of patients which averaged 65 years.

There are alternatives to mesh augmentation techniques, a recent case series of 29 patients with predominantly AO 34 C1 or C2 type fractures using a Titanium Nickel shape memory alloy (SMA) shape memory claw prosthesis had promising results. In this series, there were no nonunions or failure of fixations. The average age group of the cohort was 43 years, with 5 patients being older than 60 years of age. Those patients older than 60, all achieved bony union at 3 months. They had minimal extension lag of 5° and flexion to at least 140° at 6-month follow-up.25

Similarly, a matched cohort study looking at transosseous suture technique had good outcomes with a decreased need for metal ware removal. Chen et al reported no loss of reduction and only 2 cases of skin irritation using a transosseous braided No. 5 Ticron suture in a what were a majority of AO C3.2 fractures, these patients had an average age of 59.6 ± 14.26.26 The tension band cohort matched control group had a significantly higher n = 11/25, P = <.001 occurrence of multiple procedures for the removal of implants due to skin irritation.

In response to this increasing trend toward fixation augmentation, with permission we expanded Neumann et al’s2 treatment algorithm to account for “difficult patella fractures” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Neumann’s Algorithm for Treatment of Patella Fracture, Revised by Matthews.

| AO Classification | Treatment Method |

|---|---|

| A1 | Nonoperative |

| A2 | Screw fixation (percutaneous) |

| A3 | Screw fixation (percutaneous) |

| B1 | McLaughlin Cerclage ± screw fixation of distal pole or basket plate |

| B2 | Screw fixation |

| B2e (elderly) | Consider augmentation (mesh or plate) |

| B3 | Screw fixation and TBW or plate fixation or mesh fixation with tension band wire |

| B3e | Consider augmentation (mesh or plate) |

| C1 | Screw fixation and TBW/low profile plate |

| C1e | Consider augmentation (mesh or plate) |

| C2 | Screw fixation and TBW/low profile plate |

| C2e | Consider augmentation (mesh or plate) |

| C3 | TBW ± Cerclage wiring/low profile plate |

| C3e | Consider augmentation (mesh or plate) |

Abbreviation: TBW, tension band wire.

Limitations

The evidence presented is level 3 and publication bias may influence the results of the systematic review. A well-conducted level 1 study comparing surgical techniques is required to confirm recommendations. We concede that it is possible that our patient may require removal of implants in the future.

Summary and Conclusion

Elderly patients with comminuted fractures have a higher likelihood of fixation failure and thus warrant special consideration. The management of these patients requires solid fixation followed then early mobilization while preventing the implant cutting out of osteopenic bone.

Key Principles Identified in the Management of Patella Fracture in the Elderly Patients

Fixation must be robust enough to allow early ROM

Standard TBW and its variations remain a valid treatment option especially in simple fracture patterns

Techniques should allow for the preservation of as much patella bone as possible

Augmentation to fixation can be adopted to prevent cut out failure

Locking plates or mesh augmentation are valid treatment options, further research is required to know which modality is superior.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Dr Brent Matthews assisted surgery, reviewed patient postoperatively, contributed to initial literature review and manuscript preparation, contributed to review and submission of the manuscript. Dr Kaushik Hazratwala and Dr Sergio Barroso-Rosa performed literature review and reviewed initial manuscript with significant contribution. L. Murphy assisted for manuscript preparation. Written Permission from Dr Mirjam Neumann was obtained to reproduce her treatment algorithm.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Boström A. Fracture of the patella. A study of 422 patellar fractures. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1972;143:1–80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4516496. Accessed May 21, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neumann MV, Niemeyer P, Strohm PC. Patellar fractures—a review of classification, genesis and evaluation of treatment. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2014;81(5):303–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shabat S, Mann G, Kish B, Stern A, Sagiv P, Nyska M. Functional results after patellar fractures in elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;37(1):93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kastelec M, Veselko M. Inferior patellar pole avulsion fractures: osteosynthesis compared with pole resection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(4):696–701. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lorich DG, Warner SJ, Schottel PC, Shaffer AD, Lazaro LE, Helfet DL. Multiplanar fixation for patella fractures using a low-profile mesh plate. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(12):504–510. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor BC, Mehta S, Castaneda J, French BG, Blanchard C. Plating of patella fractures: techniques and outcomes. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(9): e231–e235. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carpenter JE, Kasman R, Matthews L. Fractures of the Patella. Instr Course Lect. 1994;43:97–108. PMID: 9097140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller MA, Liu W, Zurakowski D, Smith RM, Harris MB, Vrahas MS. Factors predicting failure of patella fixation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(4):1051–1055. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182405296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith ST, Cramer KE, Karges DE, Watson JT, Moed BR. Early complications in the operative treatment of patella fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(3):183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lazaro LE, Wellman DS, Sauro G, et al. Outcomes after operative fixation of complete articular patellar fractures: assessment of functional impairment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14): e96 1–8. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eggink KM, Jaarsma RL. Mid-term (2-8 years) follow-up of open reduction and internal fixation of patella fractures: does the surgical technique influence the outcome? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(3):399–404. doi:10.1007/s00402-010-1213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mao N, Liu D, Ni H, Tang H, Zhang Q. Comparison of the cable pin system with conventional open surgery for transverse patella fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(7):2361–2366. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2932-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luna-Pizarro D, Amato D, Arellano F, Hernández A, López-Rojas P. Comparison of a technique using a new percutaneous osteosynthesis device with conventional open surgery for displaced patella fractures in a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(8):529–535. doi:10.1097/01.bot.0000244994.67998.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dy CJ, Little MTM, Berkes MB, et al. Meta-analysis of re-operation, nonunion, and infection after open reduction and internal fixation of patella fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(4):928–932. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31825168b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kadar A, Sherman H, Glazer Y, Katz E, Steinberg EL. Predictors for nonunion, reoperation and infection after surgical fixation of patellar fracture. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(1):168–173. doi:10.1007/s00776-014-0658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. LeBrun CT, Langford JR, Sagi HC. Functional outcomes after operatively treated patella fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(7): 422–426. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e318228c1a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Juutilainen T, Patiala H, Rokkanen P, Tormala P. Biodegradable wire fixation in olecranon and patella fractures combinded with biodegradable screws or plugs and compared with metallic fixation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1995;114(6):319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gunal I, Taymaz A, Kose N, Gokturk E, Seber S. Advancement for comminuted patellar fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;1(79-B): 13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen A, Hou C, Bao J, Guo S. Comparison of biodegradable and metallic tension-band fixation for patella fractures. 38 patients followed for 2 years. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl, 1998;69(1): 39–42. doi:10.3109/17453679809002354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bonnaig NS, Casstevens C, Archdeacon MT, et al. Fix it or discard it? A retrospective analysis of functional outcomes after surgically treated patella fractures comparing ORIF with partial patellectomy. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;29(2):80–84. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shabat S, Folman Y, Mann G, Gepstein R, Fredman B, Nyska M. Rehabilitation after knee immobilization in octogenarians with patellar fractures. J Knee Surg. 2004;17(2):109–112. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15124663. Accessed November 19, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Houdek MT, Shannon SF, Watts CD, Wagner ER, Sems SA, Sierra RJ. Patella fractures prior to total knee arthroplasty: worse outcomes but equivalent survivorship. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(12):2167–2169. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang HC, Su JY, Cheng YM. Modified basket plate for inferior patellar pole avulsion fractures: a report of three cases. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2012;28(11):619–623. doi:10.1016/j.kjms.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matejcić A, Puljiz Z, Elabjer E, Bekavac-Beslin M, Ledinsky M. Multifragment fracture of the patellar apex: basket plate osteosynthesis compared with partial patellectomy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(4):403–408. doi:10.1007/s00402-008-0572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hao W, Zhou L, Sun Y, Shi P, Lui H, Wang X. Treatment of patella fracture by claw shaped memory alloy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(7):943–951. doi:10.1007/s00402-015-2241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen C, Huang H, Wu T, Lin J. Transosseous suturing of patellar fractures with braided polyester—a prospective cohort with matched historical control study. Injury. 2013;44(10):1309–1313. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]