Abstract

This study examines the demographic and social factors related to health care utilization in prisons using the 2004 Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities. The findings show that education and employment, strong predictors of health care in the community, are not associated with health care in prisons. Although female inmates have a higher disease burden than male inmates, there are no sex differences in health care usage. The factors associated with health care, however, vary for women and men. Notably, Black men are significantly more likely to utilize health care compared to White and Latino men. The findings suggest that, given the constitutionally mandated health care for inmates, prisons can potentially minimize racial disparities in care and that prisons, in general, are an important context for health care delivery in the United States.

Keywords: health care utilization, medical conditions, gender, race, prison

Introduction

Due to the Eighth Amendment’s protection against “cruel and unusual” punishment, prisons represent an “equal access” health care system (Delgado & Humm-Delgado, 2008). In the 1976 U.S. Supreme Court case Estelle v. Gamble, the court ruled that prisoners are entitled to access to care for diagnosis and treatment, a professional medical judgment, and administration of the treatment prescribed by the physician. Therefore, prisons ideally minimize differences in economic status, health coverage, and other factors that can influence access to care similar to the Veterans Health Administration (Saha et al., 2008) and the Medicare program (Schneider, Zaslavsky, & Epstein, 2002). This makes prisons uniquely situated to provide health care to individuals who are underserved in their communities (Freudenberg, 2001; Glaser & Greifinger, 1993).

The quality of health care services in prisons and jails, however, has been highly criticized. The shortcomings of health care services in U.S. correctional settings have been widely documented in academic (Delgado & Humm-Delgado, 2008; Greifinger, 2006), legal (Dockery v. Epps, 2013), journalistic (Leonard, 2012; Ridgeway & Casella, 2013), and other institutional (Human Rights Watch, 2012; National Commission on Correctional Health Care [NCCHC], 2002) forums. For example, Brinkley-Rubenstien and Turner (2013) found that HIV-positive inmates often experience a delay in medical treatment as well as low quality of care. The Health Status of Soon-to-Be Released Inmates, a comprehensive report presented to the U.S. Congress, demonstrates that many prisons are not adequately addressing inmate health (NCCHC, 2002). Not all states have system-wide treatment protocols for chronic diseases or policies and procedures for discharge planning for inmates who require ongoing care. The report concludes that there is a tremendous and largely unexploited opportunity to benefit public health by improving correctional health care practices.

It is important that health conditions be treated in prison because 95% of inmates will return to their communities without health coverage (Iglehart, 2014), although this is changing with the passage of the Affordable Care Act (Regenstein & Rosenbaum, 2014). Given the overrepresentation of men and racial/ethnic minorities in U.S. prisons, providing diagnosis and effective treatment during incarceration may help reduce population health disparities. Research has documented that improving physical health is an important step in reintegrating inmates into the community (Visher & Bakken, 2014; Wilson & Wood, 2014). One study found that inmates in Ohio and Texas reporting physical health, mental health, and substance abuse problems prior to being released have poorer employment outcomes; are more likely to need housing assistance; are heavy consumers of emergency room visits and hospitalizations without health insurance; engage in more criminal activity; and are more likely to be reincarcerated (Mallik-Kane & Visher, 2008).

This study examines the differential utilization of health care in prisons among a nationally representative sample of inmates. The main research question is, does the utilization of health care by inmates vary by demographic and other social factors? The demographic factors examined include age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, socioeconomic status, and veteran status. Childhood trauma is also examined, given the high rates among inmates (Belknap & Holsinger, 2006; James & Glaze, 2006) and the potential association with help-seeking behaviors (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Also examined are a number of factors related to the incarceration experience, such as the total number of past incarceration episodes, the number of years served, offender status, participation in programming and work assignment, and phone calls and visits from family and friends.

Methods

Data were from the 2004 BJS Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities (SISCF; Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007). The sample was designed to be nationally representative of the state inmate population. First, prisons were randomly selected for participation and then inmates were randomly selected. Participation was voluntary. The final sample included 14,499 inmates in 287 prisons. The study sample for the current analysis is limited to only inmates aged 18 and older who are non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or Latino, and who are sentenced. Patterns of missingness were examined and 94% of cases contained no missing data on the variables of interest. Given the low level of missing data, a listwise deletion was performed. This resulted in a final sample size of 12,323, which included 2,459 women and 9,864 men (85% of original sample). A subsample for analysis included only inmates who reported a current medical condition (n = 3,876; 32% of the study sample). Inmates were first asked whether they ever had problems related to the illness. A follow-up question asked whether they still had problems with the illness. The medical conditions included in the study subsample were cancer, hypertension, diabetes, heart problems, kidney problems, asthma, cirrhosis, and hepatitis.

Measures

The outcome variable was using health care for a current medical condition (yes/no). In the SISCF, inmates who reported a current health problem were asked, “Have you seen a doctor, nurse, or other health care person for this since your admission?” The study included measures for age, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic Black, Latino, marital status (never married vs. all other categories), high school/General Education Development (GED), employed prior to incarceration, and veteran status. High school/GED attainment and employment prior to incarceration are used as indicators of socioeconomic status. Childhood trauma was assessed as experiencing either sexual abuse or physical abuse. Inmates were asked to report whether they had experienced unwanted sexual contact or physical abuse prior to admission to prison. A follow-up question asked whether this occurred before the age of 18. Inmates who indicated that sexual abuse or physical abuse occurred before age 18 were coded as having experienced childhood trauma. Inmate factors included violent offender status, drug offender status, total number of past incarcerations, and the number of years served to date during the current incarceration episode. The incarceration experience was also characterized by participation in a job or educational training program since admission and the number of hours spent on work assignment in the previous week. External social support while incarcerated was indicated by whether the inmate had received telephone calls or visits from family/friends.

Analysis

First, sex differences in health conditions were examined using the full study sample (N = 12,323). Prevalence rates for the health conditions were reported for women and men. A χ2 test reports the unadjusted health differences between women and men and an odds ratio (OR) reports the differences in health conditions between women and men controlling for age and using sample weights. Similar results have been previously reported from this data set (e.g., Binswanger et al., 2010; Maruschak, 2008). Second, sex differences in each of the demographic and other study variables were examined using the subsample of inmates reporting a current medical condition (n = 3,876). Among inmates with a current medical condition, unweighted sex differences are reported using a χ2 test or t-test and weighted comparisons are reported using bivariate logistic or linear regression.

The multivariate analysis has three main logistic regression models. First, a model directly compared health care utilization between women and men with a current medical condition controlling for all demographic and other social factors. The remaining models were stratified by sex because women and men have different pathways to imprisonment (Belknap & Holsinger, 2006) and because incarcerated women have worse health (Binswanger et al., 2010; Sered & Norton-Hawk, 2008) and lower programming availability (Anderson, 2003; Eliason, Taylor, & Williams, 2004) compared to incarcerated men, and women’s prisons often struggle to meet the health care needs of women (Delgado & Humm-Delgado, 2008; Eliason et al., 2004). The stratified models used prison-level fixed effects to control for prison-level contextual and compositional effects on utilization of health care (Allison, 2009). All multivariate analyses used sample survey weights to adjust for the complex sampling design of the study.

Findings

Almost half of women (43.3%) reported at least one current medical condition compared to almost one third of men (28.5%; χ2 = 200.0, p ≤ .001; Table 1). When adjusted for age and sampling weights, men had significantly lower odds of reporting a current medical condition (OR = 0.48, p ≤ .001). Women reported a significantly higher prevalence for each health condition at the p ≤ .001 level compared to men, except for cirrhosis, which was significant only at the p ≤ .10 level. Despite the sex disparities in disease burden, there were no differences in using health care among women and men (84.9%vs. 85.6%, χ2 = 1.9, p = 0.165; Table 2). Women with a current medical condition were younger (37.9 vs. 40.0 years, t = −5.2, p ≤ .001) and less likely to be Black (35.8%vs. 44.1%, χ2 = 22.1, p ≤ .001) compared to men. Women were also less likely to have never married (38.9% vs. 45.9%, χ2 = 15.6, p ≤ .001), have been employed prior to incarceration (58.1% vs. 71.8%, χ2 = 66.3, p ≤ .001), and be a veteran (1.5% vs. 15.9%, χ2 = 152.3, p ≤ .001). The incarceration experiences of women and men also differed. Compared to men, women with a current medical condition have been incarcerated less often (1.3 vs. 1.7 episodes, t = −3.6, p ≤ .001), have served less time (2.7 vs. 5.5 years, t = −13.7, p ≤ .001), and were less likely to be violent offenders (29.7% vs. 53.8%, χ2 = 180.8, p ≤ .001) while more likely to be drug offenders (26.2% vs. 15.6%, χ2 = 58.2, p ≤ .001). There were no sex differences in participation in job/education training, hours spent in work assignment, or receiving phone calls or visits.

Table 1.

Sex Differences in Health Conditions.

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Variables | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | Adj. ORa | p |

| Any health condition | 1,065 | 43.3 | 2,811 | 28.5 | 200.0 | .000 | 0.48 | .000 |

| Asthma | 448 | 18.2 | 797 | 8.1 | 222.4 | .000 | 0.38 | .000 |

| Kidney | 161 | 6.5 | 278 | 2.8 | 79.6 | .000 | 0.39 | .000 |

| Heart problems | 208 | 8.4 | 561 | 5.7 | 25.8 | .000 | 0.60 | .000 |

| Diabetes | 125 | 5.1 | 367 | 3.7 | 9.5 | .002 | 0.60 | .000 |

| Hypertension | 413 | 16.8 | 1,324 | 13.4 | 18.4 | .000 | 0.73 | .000 |

| Cancer | 54 | 2.2 | 69 | 0.7 | 44.6 | .000 | 0.27 | .000 |

| Cirrhosis | 32 | 1.3 | 90 | 0.9 | 3.0 | .082 | 0.70 | .095 |

| Hepatitis | 228 | 9.3 | 469 | 4.8 | 75.3 | .000 | 0.46 | .000 |

| Sample size | 2,459 | 9,864 | 12,323 | |||||

Odds ratios are adjusted with age and sampling weights.

Table 2.

Descriptive and Bivariate Analysis of Study Variables by Sex.

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| (n = 1,065) | (n = 2,811) | Unweighted Comparison | Weighted Comparison | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Variables | n | % | n | % | χ2/t | p | OR/B | p |

| Medical treatment | 893 | 84.9 | 2,407 | 85.6 | 1.9 | .165 | 1.04 | .726 |

| Age (mean) | 37.9 | 40 | −5.2 | .000 | 2.27 | .000 | ||

| White | 537 | 50.4 | 1,139 | 40.5 | 30.9 | .000 | 0.63 | .000 |

| Black | 381 | 35.8 | 1,240 | 44.1 | 22.1 | .000 | 1.43 | .000 |

| Hispanic | 147 | 13.8 | 432 | 15.4 | 1.5 | .222 | 1.25 | .035 |

| Never married | 414 | 38.9 | 1,291 | 45.9 | 15.6 | .000 | 1.31 | .000 |

| High school | 694 | 65.2 | 1,894 | 67.4 | 1.7 | .191 | 1.10 | .225 |

| Employed | 619 | 58.1 | 2,018 | 71.8 | 66.3 | .000 | 1.80 | .000 |

| Veteran | 16 | 1.5 | 447 | 15.9 | 152.3 | .000 | 11.20 | .000 |

| Childhood trauma | 157 | 14.7 | 358 | 12.7 | 2.7 | .100 | 0.81 | .048 |

| Past incarcerations (mean) | 1.3 | 1.7 | −3.6 | .000 | 0.48 | .000 | ||

| Years served (mean) | 2.7 | 5.5 | −13.7 | .000 | 2.80 | .000 | ||

| Violent offender | 316 | 29.7 | 1,513 | 53.8 | 180.8 | .000 | 2.76 | .000 |

| Drug offender | 279 | 26.2 | 437 | 15.6 | 58.2 | .000 | 0.56 | .000 |

| Job/education training | 505 | 47.4 | 1,311 | 46.6 | 0.2 | .664 | 0.95 | .519 |

| Hours in work assign (mean) | 14.7 | 13.8 | 1.6 | .106 | −0.86 | .140 | ||

| Phone calls | 877 | 82.4 | 2,360 | 84.0 | 1.5 | .228 | 0.97 | .796 |

| Visits | 329 | 30.9 | 785 | 27.9 | 3.3 | .069 | 0.86 | .064 |

| Sample size | 1,065 | 2,811 | 3,876 | |||||

Table 3 presents the results from the multivariate logistic regression. Model 1 confirms that there were no sex differences in utilization of health care (OR = 0.92, p = .528). For every 1 year increase in age, inmates had 6% higher odds of utilizing health care (OR = 1.06, p ≤ .001). Black inmates had higher odds of using health care compared to Whites (OR = 1.40, p ≤ .01), while there were no Latino–White differences. An additional model (not shown) changed the reference category to Black. The findings show that both Whites (OR = 0.72, p = .003) and Latinos (OR = 0.76, p = .077) had significantly lower odds of health care than Blacks. Finally, length of time in prison (OR = 1.06, p ≤ .001) and participation in job/education programming (OR = 1.27, p ≤ .05) were positively associated with health care.

Table 3.

Results From Multivariate Logistic Regression Examining Utilization of Health Care.

| Model 1 | Model 2a | Model 3a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Total | Women | Men | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Variables | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p |

| Male | 0.92 | .528 | — | — | ||

| Age | 1.06 | .000 | 1.05 | .000 | 1.06 | .000 |

| Black | 1.40 | .003 | 1.25 | .324 | 1.40 | .022 |

| Latino | 1.06 | .740 | 1.43 | .230 | 0.89 | .549 |

| Never married | 1.10 | .449 | 1.30 | .231 | 1.09 | .540 |

| High school | 1.13 | .340 | 1.12 | .562 | 1.01 | .936 |

| Employed | 0.88 | .247 | 0.81 | .284 | 0.94 | .672 |

| Veteran | 0.82 | .247 | 0.40 | .177 | 0.82 | .322 |

| Childhood trauma | 0.76 | .059 | 1.62 | .091 | 0.68 | .023 |

| Past incarcerations | 0.99 | .732 | 1.02 | .641 | 1.00 | .790 |

| Years served | 1.06 | .000 | 1.16 | .002 | 1.06 | .001 |

| Violent offender | 0.93 | .600 | 0.94 | .792 | 0.89 | .427 |

| Drug offender | 0.81 | .242 | 1.01 | .962 | 0.91 | .612 |

| Job/education training | 1.27 | .025 | 1.62 | .016 | 0.16 | .203 |

| Hours in works assignment | 1.00 | .178 | 1.01 | .042 | 0.00 | .479 |

| Phone calls | 1.02 | .892 | 1.62 | .070 | 0.23 | .325 |

| Visits | 1.07 | .515 | 1.19 | .425 | 0.14 | .944 |

| Observations | 3,876 | 967b | 2,323b | |||

Includes prison fixed effects.

Sample size reduced due to lack of variation in the outcome for some prisons.

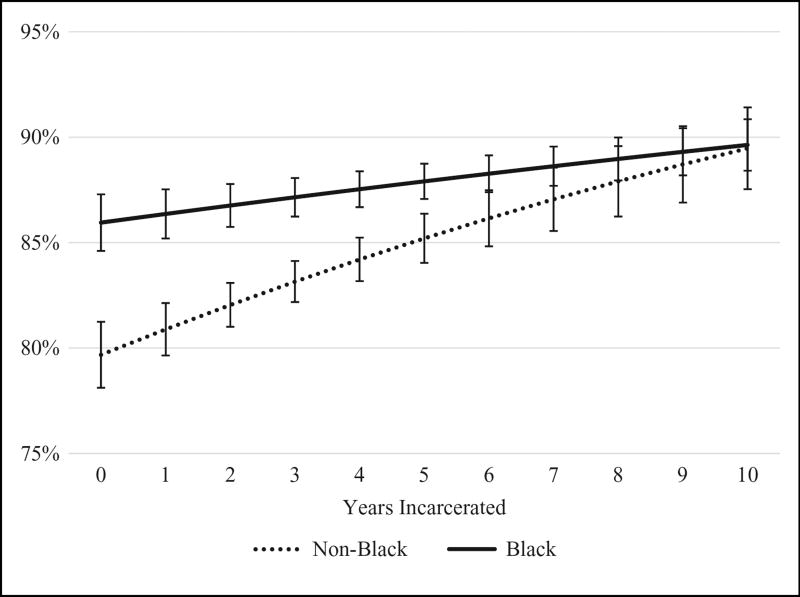

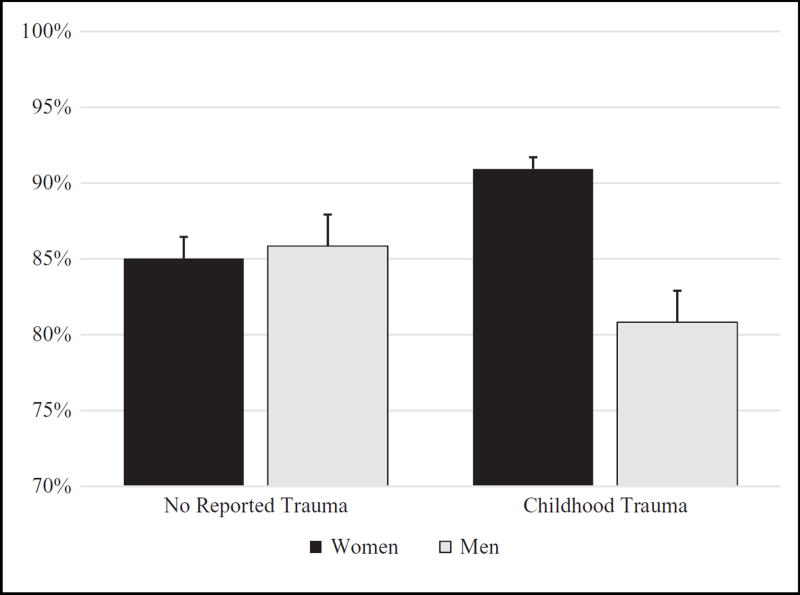

Models 2 and 3 (Table 3) present the findings of the multivariate fixed effects logistic regression. The Black–White differences were found specifically for men (OR = 1.40, p ≤ .05). Figure 1 presents the predicted probability of health care for Black and non-Black men over time in prison. It shows that Black men had a higher probability of health care compared to non-Black men during the first 5 years of incarceration. As time in prison increases, the differences converged. It is worth noting that the average length of incarceration for men was just over 5 years. The models also show an interesting interaction with childhood trauma. This relationship was graphed in Figure 2. There were no sex differences in health care among those who reported no childhood trauma. Among inmates who reported childhood trauma, however, women were more likely to use health care services. In fact, women who reported childhood trauma were significantly more likely to use health care than women who did not report childhood trauma, while the reverse was true for men. Finally, participation in prison activities (e.g., job/education programming, hours spent in work assignment) had a positive influence on health care for women but not men.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of health care utilization with 95% confidence intervals for Black and non-Black men by years incarcerated (less than 1 year to 10 years).

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of health care utilization with 95% confidence intervals for women and men who did and did not report childhood trauma.

Discussion

The health care of inmates in prison has remained a poorly understood topic of research (Binswanger, Redmond, Steiner, & Hicks, 2011; Moore & Elkavich, 2008). Given that older inmates are a growing population (Delgado & Humm-Delgado, 2008), the health care needs of inmates will continue to increase since increasing age also means increasing incidences of chronic illness and disabilities (Mitka, 2004). Given the constitutionally mandated health care for inmates, prisons can help minimize population disparities in health care. Indeed, the current study found that education and employment, strong predictors for health care in the community (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012), are not associated with health care in prisons. Also, even though female inmates have a higher disease burden than male inmates, a finding previously documented (Binswanger et al., 2010), there are no sex differences in health care usage. The factors associated with health care, however, vary for women and men. For example, social support and social networks appeared to be more important for health care for women. This suggests that increasing women’s opportunities to build and maintain relationships both inside and outside of prison may be beneficial for their health. A second key finding is that men who experienced childhood trauma have lower health care usage. This reinforces the importance of offering trauma-informed care for adult male prisoners (Levenson, Willis, & Prescott, 2014), an issue that has been well documented for female prisoners (e.g., Covington & Bloom, 2006).

A third key finding is that Black men are significantly more likely to utilize treatment compared to every other racial group. The findings suggest that prisons may be an important site for health care for Black men, given their low levels of access to health care outside of prison. Research has consistently documented Black–White disparities in health care for noninstitutionalized adults (Hayward, Miles, Crimmins, & Yang, 2000; Marmot, 2005). For example, a 2007 Kaiser Family Foundation report provides evidence for racial differences in health insurance coverage, access to primary care, and treatment for specific medical conditions (James, Thomas, Lillie-Blanton, & Garfield, 2007). Some studies find that racial disparities persist even after adjustment for socioeconomic differences and other health care-related factors (Kressin & Petersen, 2001; Mayberry, Mili, & Ofili, 2000). Research with criminal justice–involved populations also supports this view. Mortality research documents that Black male prisoners have lower death rates than Black male non-prisoners largely because of protections from external causes of death (Patterson, 2010; Spaulding et al., 2011), suggesting a potential prison health benefit for Black men. A study on health care expenditures found that individuals with recent criminal justice involvement make up 4.2% of the U.S. adult population, yet account for an estimated 7.2% of hospital expenditures and 8.5% of emergency department expenditures (Frank, Linder, Becker, Fiellin, & Wang, 2014). Since Black men are overrepresented in criminal justice–involved populations (Alexander, 2010; Clear, 2007; Pettit & Western, 2004) and underrepresented in community health care coverage (Mayberry et al., 2000; Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2002), providing quality health care in prisons, as well as in transition to the community after prison, can potentially contribute to reducing Black–White health disparities in the United States.

Limitations

There are several study limitations that need to be considered. First, the study is unable to account for access to health care prior to prison. Additionally, health care utilization is conceptualized as receiving any care. It does not capture the number of medical visits, the type of treatment offered, or the quality of the services provided. The conclusions of this study are attenuated because of this limited conceptualization of health care utilization. Second, it is unable to account for the timing of diagnosis, severity of symptoms, or the patterns of treatment. Each of these could impact who decides to seek health care. Perhaps the greatest limitation is that the health measures rely on self-report. This severely limits the validity of this study. However, the SISCF is the best sample available to answer the research question because it is the only large, nationally representative survey of inmates available in the United States. Surveys that include measured health such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey exclude institutionalized populations (Ahalt, Binswanger, Steinman, Tulsky, & Williams, 2011). Relatedly, it is possible that different conclusions would be found with more recent data, given the recent changes in correctional health care spending and health care policy (e.g., Boutwell & Freedman, 2014; Iglehart, 2014). The data used in this study are 10 years old. It is important that correctional health and health care continue to be monitored at the national level (NCCHC, 2009).

Conclusion

This study suggests that prisons are an important site for health and health care delivery in the United States similar to schools (Eccles & Roeser, 2011; Ringeisen, Henderson, & Hoagwood, 2003) and the military (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006; Tuerk, Grubaugh, Hamner, & Foa, 2009). More research is needed to understand how health care utilization varies by prison and the environmental factors that influence whether inmates use health care services. Future research should also consider both the potential health benefits of prison and the potential negative effects of imprisonment on health (e.g., stress, injury, communicable diseases) in order to better understand how prisons influence population health (Binswanger et al., 2011; Brinkley-Rubenstein, 2013).

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Support for this study was provided by the NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Individual Fellowship (F31 DA037645) funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the NIDA-funded National Hispanic Science Network Interdisciplinary Research Training Institute on Drug Abuse at the University of Southern California (R25 DA026401), the National Science Foundation (NSF) Sociology Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant (#1401061), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) funded University of Colorado Population Center (R24 HD066613).

Footnotes

The NICHD, NIDA, and NSF had no role in study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author disclosed no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article. For information about JCHC’s disclosure policy, please see the Self-Study Program.

References

- Ahalt C, Binswanger IA, Steinman M, Tulsky J, Williams BA. Confined to ignorance: The absence of prisoner information from nationally representative health data sets. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;27:160–166. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1858-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M. The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Fixed effects regression models. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TL. Issues in the availability of health care for women prisoners. In: Sharp SF, editor. The incarcerated woman. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2003. pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J, Holsinger K. The gendered nature of risk factors for delinquency. Feminist Criminology. 2006;1:48–71. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Merrill JO, Krueger PM, White MC, Booth RE, Elmore JG. Gender differences in chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance-dependence disorders among jail inmates. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:476–482. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Redmond N, Steiner JF, Hicks LS. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: An agenda for further research and action. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;89:98–107. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutwell A, Freedman J. Coverage expansion and the criminal justice-involved population: Implications for plans and service connectivity. Health Affairs. 2014;33:482–486. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubenstein L. Incarceration as a catalyst for worsening health. Health and Justice. 2013;1:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubenstein L, Turner WL. Health impact of incarceration on HIV-positive African American males: A qualitative exploration. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2013;27:450–458. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Survey of inmates in state and federal correctional facilities, 2004 (ICPSR04572-v1) Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2007. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04572.v1. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/index.html.

- Clear T. Imprisoning communities: How mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Covington SS, Bloom BE. Gender responsive treatment and services in correctional settings. Women and Therapy. 2006;29:69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Humm-Delgado D. Health and health care in the nation’s prisons: Issues, challenges, and policies. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dockery v. Epps. Civil Action No: 3: 13CV326TSL-JMR (S.D. Miss. 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Roeser RW. Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ, Taylor JY, Williams R. Physical health of women in prison: Relationship to oppression. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2004;10:175–203. [Google Scholar]

- Frank JW, Linder JA, Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Wang EA. Increased hospital and emergency department utilization by individuals with recent criminal justice involvement: Results of a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29:1226–1233. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2877-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: A review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78:214–235. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser JB, Greifinger RB. Correctional health care: A public health opportunity. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;118:139–145. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greifinger RB. Inmates as public health sentinels. Journal of Law and Policy. 2006;22:253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward MD, Miles TP, Crimmins EM, Yang Y. The significance of socioeconomic status in explaining the racial gap in chronic health conditions. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:910–930. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. Old behind bars: The aging prison population in the United States. New York, NY: Author; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Iglehart JK. The ACA opens the door for two vulnerable populations. Health Affairs. 2014;33:358. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C, Thomas M, Lillie-Blanton M, Garfield R. Key facts: Race, ethnicity and medical care. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates (NCJ 213600) Washington DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kressin NR, Petersen LA. Racial differences in the use of invasive cardiovascular procedures: Review of the literature and prescription for future research. Annual Review of Internal Medicine. 2001;135:352–366. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K. Privatized prison health care scrutinized. The Washington Post. 2012 Jul 21; Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/privatized-prison-health-care-scrutinized/2012/07/21/gJQAgsp70W_story.html.

- Levenson JS, Willis GM, Prescott DS. Adverse childhood experiences in the lives of male sex offenders: Implications for trauma-informed care. Sexual Abuse. 2014 May 28; doi: 10.1177/1079063214535819. Advance Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik-Kane K, Visher CA. Health and prisoner reentry: How physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet. 2005;365:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM. Medical problems of prisoners (NCJ 221740) Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry RM, Mili F, Ofili E. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57:108–145. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitka M. Aging prisoners stressing health care system. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:423–424. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LD, Elkavich A. Who’s using and who’s doing time. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:782–786. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: With special feature on socioeconomic status and health. Hyattsville, MD: Author; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care. The health status of soon-to-be-released inmates: A report to Congress. Chicago, IL: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care. Health services research in correctional settings (position statement) Chicago, IL: Author; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson EJ. Incarcerating death: Mortality in U.S. state correctional facilities, 1985–1998. Demography. 2010;47:587–607. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Regenstein M, Rosenbaum S. What the Affordable Care Act means for people with jail stays. Health Affairs. 2014;33:448–454. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway J, Casella J. America’s 10 worst prisons. Mother Jones. 2013 May 1; Retrieved from http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/05/10-worst-prisons-america-part-1-adx.

- Ringeisen H, Henderson K, Hoagwood K. Context matters: Schools and the ‘‘research to practice gap’’ in children’s mental health. School Psychology Review. 2003;32:153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, Tippens KM, Weeks C, Ibrahim S. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA health care system: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:654–671. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Epstein AM. Racial disparities in the quality of care for enrollees in Medicare managed systems. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287:1288–1294. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sered S, Norton-Hawk M. Disrupted lives, fragmented care: Illness experiences of criminalized women. Women and Health. 2008;48:43–61. doi: 10.1080/03630240802131999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding AC, Seals RM, McCallum VA, Perez SD, Brzozowski AK, Steenland NK. Prisoner survival inside and outside of the institution: Implications for health-care planning. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;173:479–487. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk PW, Grubaugh AL, Hamner MB, Foa EB. Diagnosis and treatment of PTSD-related compulsive checking behaviors in veterans of the Iraq War: The influence of military context on the expression of PTSD symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:762–767. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08091315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visher CA, Bakken NW. Reentry challenges facing women with mental health problems. Women and Health. 2014;54:768–780. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.932889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JA, Wood PB. Dissecting the relationship between mental illness and return to incarceration. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2014;42:527–537. [Google Scholar]