Abstract

Acquired immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) has long been assumed to depend on the presence of anticapsular antibodies. We found, however, that colonization with live pneumococci of serotypes 6B, 7F, or 14 protected mice against recolonization by any of the serotypes and that protection from acquisition of a heterologous or homologous strain did not depend on anticapsular antibody. Further, intranasal immunization by live pneumococcal colonization or by a killed, nonencapsulated whole-cell vaccine protected antibody-deficient mice against colonization, suggesting independence of antibodies to any pneumococcal antigens. Protection by intranasal immunization with whole-cell vaccine was completely abrogated in T cell-deficient mice, and in mice that were congenitally deficient in CD4+ T cells or depleted of these cells at the time of challenge. In contrast, mice congenitally deficient in, or depleted of, CD8+ T cells were fully protected. Protection in this model was observed beyond 2 months after immunization, arguing against innate or nonspecific immune mechanisms. Thus, we find that immunity to pneumococcal colonization can be induced in the absence of antibody, independent of the capsular type, and this protection requires the presence of CD4+ T cells at the time of challenge.

Keywords: Streptococcus pneumoniae, cell-mediated immunity, vaccine

Almost 1 million children in the developing world die of infections due to Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) each year (1). Pneumococcus is considered an “extracellular” bacterial pathogen, i.e., it is killed upon ingestion by phagocytic cells. Ingestion is facilitated by antibody (Ab) to its capsular polysaccharides (PS), of which there are at least 90 different serotypes. The two existing pneumococcal vaccines are based on injected mixtures of PS. Plain (unconjugated) PS vaccine contains 23 serotypes but is not efficacious in children <2 years old and therefore fails to protect those at highest risk. Protein-conjugated PS contains seven serotypes and protects infants (2), but it is difficult to manufacture (resulting in repeated shortages), is expensive, needs refrigeration, requires multiple injections, and does not include many of the capsular serotypes that cause pneumococcal disease in the developing world. Furthermore, serotype replacement, whereby pneumococcal serotypes not included in the conjugate vaccine become more prevalent causes of colonization and disease, has already been observed in clinical trials (3) and in epidemiologic studies (4) after implementation of conjugate vaccine immunization programs. Therefore, despite the success of the capsule-based vaccines, alternative strategies are urgently needed.

The success of serum therapy (passive transfer of anticapsular Ab from hyperimmune animals) and the efficacy of PS and PS-protein conjugate vaccines have clearly demonstrated that anticapsular Ab alone is sufficient to treat or prevent pneumococcal disease. Furthermore, studies in animals (5) and humans (6) clearly demonstrate that anticapsular Abs can protect against nasopharyngeal pneumococcal colonization, which precedes pneumococcal disease (7). However, several observations suggest the hypothesis that natural immunity to colonization might nonetheless be acquired independently of anticapsular Ab. The age-specific incidence of pneumococcal disease in humans declines simultaneously and in a parallel fashion for a wide range of serotypes and well before natural acquisition of anticapsular Abs (8), suggesting a common and probably capsular serotype-independent mechanism of protection. Additionally, we have previously shown that a vaccine made from killed, unencapsulated pneumococci whole-cell vaccine (WCV) given intranasally to mice with cholera toxin (CT) as an adjuvant prevents colonization by pneumococci of various capsular serotypes (9, 10). More recently, McCool and Weiser (11) reported that clearance of carriage of a recently acquired pneumococcal strain in mice could occur independently of Ab, further supporting the possibility that other components of the immune response (whether innate or acquired, specific or not) may play an important role in this process, but the mechanisms for this protection have not been elucidated to date.

The purpose of our studies was to identify immunologic mechanisms of prevention of pneumococcal colonization. Here, we show that long-lasting immunity to pneumococcal colonization can be conferred independently of immunity to the PS capsule, in a fashion that is Ab-independent but dependent on CD4+ T cells present at the time of challenge. Protection conferred by these T cells was observed >2 months beyond immunization, arguing against nonspecific or innate responses. Our data therefore indicate a previously unrecognized, critical role for cellular immunity, independent of Ab, in the prevention of colonization by pneumococcus.

Methods

Bacterial Strains and Immunogens. S. pneumoniae strains TIGR4J, TIGR4:6B4, TIGR4:7F4, and TIGR4:144 are isogenic variants (12) of S. pneumoniae strain TIGR4. TIGR4J is acapsular; the other strains express serotype 6B, 7F, or 14 capsules, respectively (12). Strain 0603 is a serotype 6B clinical strain (9). Frozen midlog-phase aliquots were thawed and diluted to ≈106 colony-forming units (cfu) per 10 μl of intranasal inoculum for challenge. WCV was derived from strain RX1AL-, a capsule- and autolysin-negative mutant, and prepared as described in ref. 9. The final vaccine mixture contained 108 (killed) cfu of this strain plus 1 μg of CT (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) per 10-μl dose. Control mice were immunized with 1 μg of CT in 10 μl of saline.

Animal Models. To assess the role of capsular serotype in protection against nasopharyngeal carriage, groups of 20 C57BL/6J mice (female, age 6 weeks, The Jackson Laboratories) were randomized by cage to receive ≈106 cfu of TIGR4:6B4, TIGR4:7F4, TIGR4:144, or saline control, as described in ref. 9. Inoculations were given three times at weekly intervals. One week after the last inoculation, two i.p. injections of 1 mg of rifampin (Sigma) in 0.25 ml were provided 1 day apart [a dose that effectively eradicates pneumococcal colonization and does not prevent subsequent colonization (data not shown)]. Two weeks later, serum and saliva samples were obtained from anesthetized mice. Salivation was induced by i.p injection of 100 μg of pilocarpine (Sigma). Saliva was kept on ice, an equal volume of 1× PBS containing 5% FCS (HyClone) and 12.5 μg/ml aprotinin (Sigma) was added, and samples were frozen at -70°C until use. Mice were challenged intranasally with ≈106 cfu of one of the TIGR4 serotype variants. At 1 week after challenge, the mice were killed by CO2 inhalation; an upper respiratory wash was performed by instilling sterile, nonbacteriostatic saline retrograde through the transected trachea and collecting the first six drops (≈0.1 ml) from the nostrils. An animal was considered to be nasally colonized if at least 1 cfu per 100 μl of wash fluid was detected.

To test the role of Ab in protection, C57BL/6J, muMT-/- [B6.129S2-Igh-6tm1Cgn/J, in which B cell development is blocked at the pro-B stage (13)], nu-/- (nude mice, lacking T cells) and their respective nu+/- littermates were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories. β2-microglobulin (β2m)-deficient mice [B6.129-B2mtm1 N5 (14)] and MHC Class II-deficient mice [B6.129-H2-Ab1tm1Gru N12, with a disruption of the H2-Ab1 gene (15)] were purchased from Taconic Farms; these mice lack CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively. Mice were randomized by cage to receive vaccine or control preparations (live 0603, killed WCV/CT, CT alone, or saline; mice lacking T cells or T cell subsets received only WCV/CT or CT). Immunization was delivered as described above except for the concentration of bacteria (106 cfu of 0603; 108 cfu of killed WCV/CT). Inoculations were given at weekly intervals (thrice for strain 0603 and saline; twice for WCV/CT or CT). Only the mice that received strain 0603 or saline received rifampin treatment. All mice were challenged with 106 cfu of strain 0603 (3 weeks after immunization with WCV/CT or CT; 2 weeks after rifampin treatment for mice that received strain 0603 or saline). One week after challenge, mice were killed, and nasal wash was obtained as above.

To test the role of T cell subsets at the time of challenge and also to evaluate whether protection was long-lasting, the same protocol with WCV/CT or CT was followed as above, except that the pneumococcal challenge was performed 10 weeks after the last immunization. One group of mice (n = 16) received intranasal CT, and four groups received WCV/CT (n = 12-16 for each group). To deplete T cell populations, three groups of WCV/CT mice were administered 1 mg of Abs 1 day before, 1 day after, and 4 days after the challenge (16). A control group received rat IgG (Calbiochem), whereas experimental groups received either rat anti-mouse CD4 monoclonal IgG2b (purified from hybridoma GK1.5, American Type Culture Collection) or rat anti-mouse CD8 monoclonal IgG2a (purified from hybridoma 53-6.72, American Type Culture Collection). More than 95% of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were depleted from the spleens of respectively treated animals, as assessed by flow cytometry.

ELISA. ELISAs were performed on serum and saliva samples collected before exposure to the challenge strain. A subset of at least 10 mice exposed to serotype 6B, 7F, or 14 or saline was evaluated for salivary IgA and serum IgG and IgM Abs to capsular PS 6B, 7F, and 14. In this case, saliva and serum samples were preabsorbed with both C-PS and type 22F capsular PS at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. MuMT-/- mice were evaluated for Ig and IgG (serum) Abs to whole cells of strain TIGR4J and IgA (saliva) Abs to the pneumococcal proteins PsaA and PspA and to TIGR4J. Whole-cell ELISA was performed as follows. TIGR4J strain was grown in THY to late-log phase, harvested by centrifugation, killed by 1-h incubation in 70% EtOH (vol/vol), and washed extensively to remove any residual EtOH. Ninety-six-well ELISA plates were coated overnight with 0.1 ml of this killed TIGR4J preparation (corresponding to a concentration of 108 cfu/ml). After blocking in PBS/Tween (0.05%) with 5% FCS, dilutions of serum or saliva were added and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Plates were washed, and secondary Ab to mouse Ig was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The plates were washed and developed with SureBlue 3,3′5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine microwell peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories).

Statistical Analysis. Proportions colonized were compared by Fisher's exact test, and colonization density was evaluated by the Mann-Whitney U test or by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

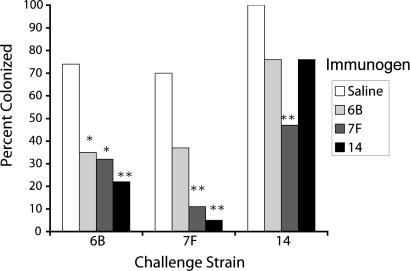

Prior Exposure to Homologous and Heterologous Capsular Serotypes Confers Similar Protection Against Subsequent Pneumococcal Colonization. The role of capsule in immunity to colonization was examined. C57BL/6J mice were intranasally inoculated thrice at weekly intervals with 106 cfu of serotype 6B, 7F, or 14 variants of pneumococcal strain TIGR4, which were isogenic except for the cps locus (12). A week later, colonization was cleared with rifampin treatment (9). Two weeks afterward, mice of each group were challenged intranasally with 106 cfu of one each of the three strains. One week later, colonization was assessed by tracheal wash. Fig. 1 shows the proportion of animals colonized with each serotype, with naïve (saline controls) compared with animals that had previously been exposed to one of the three strains. Prior colonization offered protection ranging from 24% to 93%, but not statistically greater with the homologous than with the two heterologous serotypes. Consistent with this finding, no anticapsular Ab was measurable in serum or saliva obtained from animals before the final challenge (9), suggesting that the mechanism of protection is independent of such Abs. Therefore, these studies show that exposure to homologous and heterologous capsular serotypes confer similar protection against subsequent pneumococcal colonization, suggesting that immunity to the capsular PS does not play a critical role in prevention of colonization.

Fig. 1.

Prior exposure to homologous and heterologous capsular serotypes confers similar protection against pneumococcal colonization. Significant protection was observed in four of six heterologous challenges and two of three homologous challenges; for none of the three challenges did prior homologous colonization provide the greatest protection. n = 17-20 mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

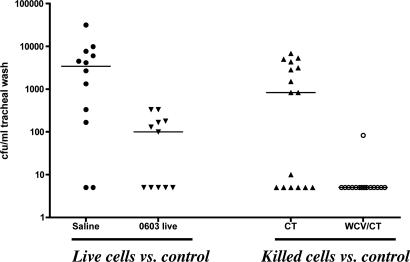

Prevention of Pneumococcal Colonization Is Independent of Ab. Next, we evaluated whether Abs of any specificity were involved in prevention of pneumococcal colonization in this model. Immunization was performed by exposure to live pneumococci (as described above) and also by intranasal vaccination with a killed, unencapsulated pneumococcal preparation (WCV) that we previously demonstrated to be highly effective in the prevention of pneumococcal colonization due to several different serotypes (9, 10). MuMT-/- (Ab-deficient) mice were immunized intranasally, either thrice with live serotype 6B pneumococcus strain 0603 (followed by rifampin treatment as above) or twice with WCV with CT as an adjuvant. Four weeks after immunization, mice were challenged intranasally with strain 0603. Colonization evaluated 7 days after challenge was significantly reduced by the previous exposure to live strain 0603 and almost completely prevented by the immunization with WCV/CT (Fig. 2). No serum or salivary Ab to pneumococcal antigens was detected, confirming that protection against colonization in this model is independent of systemic and mucosal Ab.

Fig. 2.

Acquired immunity against pneumococcal colonization is Ab-independent. MuMT-/- mice deficient in Ab production were intranasally immunized with 106 live type 6 pneumococcal strain 0603 (saline as control) or with killed unencapsulated WCV plus CT (CT as control). They were subsequently challenged with strain 0603, and nasopharyngeal colonization was determined 1 week later by tracheal washes as described. Shown are the cfu per milliliter of tracheal wash for each mouse. The line represents the median density of colonization for each group. Protection was significant for mice exposed to strain 0603 vs. saline controls (P = 0.006) and for mice exposed to WCV/CT vs. CT controls (P = 0.004).

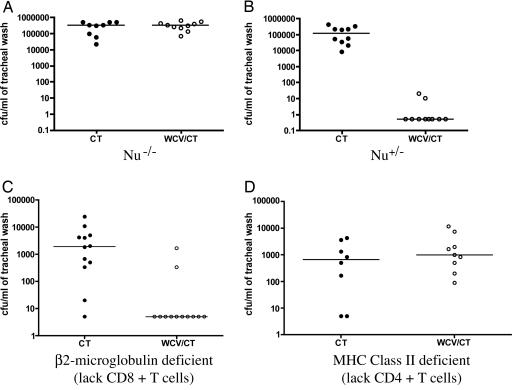

Immunity to Pneumococcal Colonization Depends on CD4+ T Cells, Which Must Be Present at the Time of Challenge. Because immunity to colonization elicited by the WCV is long-lasting [complete protection against colonization is observed >2 months since the last immunization (9)], we hypothesized that cognate T cells may be playing a role in protection. Therefore, to test T cell dependence of the protection, the vaccination protocol with WCV (9) was repeated in the following types of mice: (i) T cell-deficient (nu-/-) and heterozygote control (nu+/-) mice; (ii) β2m-deficient (β2m-/-) mice that lack CD8+ T cells (14); and (iii) MHC Class II-deficient mice (H2-Abl-/-) that lack CD4+ T cells (15). As in the case of wild-type (WT) mice, protection was observed in the heterozygote controls and in the β2m-/- mice, but was completely abrogated in the nu-/- and H2-Abl-/- mice (Fig. 3). It is noteworthy that CD4+ T cell-deficient mice that received CT only (and thus were naïve to pneumococci) were no more heavily colonized than CD8+ T cell-deficient mice immunized with CT. These data, which do not indicate an important role for naïve CD4+ T cells in the prevention of nasopharyngeal colonization, are in contrast with findings by Kadioglu et al. (17) suggesting a role of naïve CD4+ T cells in the protection against invasive disease. Overall, these results suggested that, after mucosal exposure to pneumococci, CD4+ T cells may be required for protection against pneumococcal colonization.

Fig. 3.

Acquired immunity to pneumococcal colonization requires CD4+ T cells. (A and B) Nude mice (nu-/-) and their heterozygote controls (WT) were immunized with CT or WCV/CT as in Fig. 2 and subsequently challenged with strain 0603. WT mice immunized with WCV/CT were significantly protected compared with WT mice that received CT alone (comparison of density of colonization, P < 0.001), whereas nu-/- mice immunized with WCV/CT were not protected (P = 1.0). (C) Mice lacking CD8+ T cells [β2m-deficient (16)] were significantly protected when immunized with WCV/CT vs. CT controls (P = 0.006). (D) Mice lacking CD4+ T cells (with a disruption of the MHC class II H2-Ab1 gene) were not protected when immunized with WCV/CT vs. CT controls (P = 0.36).

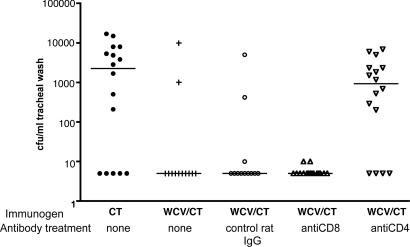

To assess whether CD4+ T cells were required at the time of challenge as part of the mechanism of protection, C57BL/6 mice were immunized with WCV as before and, 10 weeks after the second immunization, were selectively depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ cells, by using anti-CD4 or -CD8 monoclonal Abs. Control groups received intranasal CT alone or WCV/CT followed by treatment with irrelevant Ab or no Ab. Mice that received WCV/CT were all significantly protected against pneumococcal colonization except those that were depleted of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4). Because T cell depletion was performed >2 months after immunization, these results argue strongly against nonspecific, innate responses to immunization and suggest a role of acquired immunity mediated by CD4+ T cells at the time of challenge.

Fig. 4.

Protection requires the presence of CD4+ T cells at the time of challenge. Depletion of CD4+ T cells, but not of CD8+ T cells, at the time of challenge abrogated WCV protection in C57BL6/J mice. Mice immunized with WCV/CT and subsequently treated with rat IgG or anti-CD8 Ab were significantly protected against nasopharyngeal colonization compared with mice that were immunized with CT alone (P < 0.05 for each comparison) and were indistinguishable from mice that received WCV/CT with no additional treatment (P > 0.5). In contrast, mice treated with anti-CD4 Ab were not protected (P = 0.46 vs. CT group) and were significantly more colonized than mice in the three other WCV/CT immunized groups (P < 0.05). The line represents the median density of colonization for each group.

Discussion

Immunity to extracellular, encapsulated bacteria has long been assumed to depend on the humoral arm of the immune system. In the case of pneumococcus in particular, immunity to disease and colonization generally has been associated with Abs to the main virulence factor of the organism, the capsular PS. This concept has even led to the conclusion that, from the perspective of the host immune system, each different pneumococcal serotype represents a different potential pathogen, as determined predominantly by the capsular PS (18). Recently, however, data derived from two different approaches have challenged this generally accepted view. Data from sero-epidemiologic studies argue against a primary role of anticapsular Ab in the prevention of pneumococcal disease (8). Unimmunized children demonstrate a significant reduction in susceptibility to pneumococcal invasive disease before the development of measurable systemic anticapsular Abs. Secondly, this age-related decline in pneumococcal invasive disease is observed across serotypes, arguing strongly for a serotype-independent, common mechanism of protection. In a murine model of pneumococcal colonization, McCool and Weiser (11) demonstrated that clearance of pneumococcal carriage did not depend on the presence of Ab, because Ab-deficient mice were able to clear pneumococcal colonization similarly to WT mice, although the responsible mechanisms were not elucidated.

The data presented herein suggest an Ab-independent, CD4+ T cell-dependent mechanism by which immunity to pneumococcal colonization can be acquired after exposure to pneumococci. To our knowledge, such a mechanism of protection against extracellular, encapsulated bacteria has not previously been demonstrated. Although T cell help is required for the primary induction of an anticapsular Ab response by capsular PS-protein conjugate vaccines, it is the Abs induced by such vaccines that are the effectors of immunity. Moreover, the T cell help is required at the time of immunization with conjugate vaccines, to induce affinity maturation, class switching, and B cell memory (19, 20), but may not be required at the time of challenge, as it is in the experiments described here. Stimulation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells by Group A streptococci has recently been described, but no evidence for a protective role of these cells was obtained (21).

The role of CD4+ T cells in pneumococcal pathogenesis has been evaluated in other studies. Kadioglu et al. (17) have shown that mice lacking CD4+ T cells due to a deletion of MHC Class II are compromised in host defense against systemic pneumococcal challenge in the first 3 days after infection. These studies were conducted in naïve mice. By contrast, in our colonization model, MHC Class II-deficient mice exposed to CT only (and thus naïve to pneumococcus) were no more heavily colonized than controls that lacked CD8+ T cells. Thus, whereas Kadioglu et al. (17) showed the importance of CD4+ T cells in primary clearance of pneumococci during invasive disease in naïve mice, we have shown the involvement of CD4+ T cells in a long-lasting, acquired immune response. Kadioglu et al. (17, 22) also showed that T cells are rapidly recruited after pneumococcal pulmonary infection and that human CD4+ T cells migrate toward pneumococci in vitro, in a fashion that depends, at least in part, on the cytotoxin pneumolysin. It would be valuable to understand to what extent the induction of acquired immunity during initial exposure to live or killed pneumococci in our system depends on migration and activation of CD4+ T cells through a pneumolysin-dependent mechanism of the sort described by Kadioglu et al. (17, 22).

Thus, in mice, nonserotype-specific resistance to colonization can be induced by intranasal exposure to live or killed bacteria in the absence of anticapsular Ab and, more surprisingly, without Ab of any specificity. Instead, long-lasting WCV-induced immunity is mediated by CD4+ T cells. It remains to be determined how closely our non-type-specific immunization by intranasal inoculation models the acquisition of natural immunity and whether this CD4+ T cell-dependent phenomenon occurs in humans. Individuals with profound Ab deficiency (such as Bruton's agammaglobulinemia) are known to be at high risk for invasive pneumococcal disease (23), but whether there is like-wise a high risk of nasopharyngeal colonization is not clear. Moreover, it is unknown whether the critical defect in such Ab-deficient individuals involves anticapsular Ab or Ab against one or more other pneumococcal antigens.

Anticapsular Abs not only prevent invasion but, as shown by active and passive immunization (5, 24), are sufficient to prevent pneumococcal colonization; however, they may not be necessary. As mentioned above, children naturally acquire resistance to invasive disease from all serotypes on a similar timescale and before the appearance of anticapsular Abs, suggesting that other immune effectors may be involved. Abs to noncapsular antigens are sufficient in some animal models to protect against colonization or invasive disease, but the role of these Abs in natural protection in humans is also uncertain. In normal children, colonization persists in the first years of life, despite the appearance of such Abs (25), which thus might merely be markers of exposure, not effectors of protection.

During invasive disease, the pneumococcus is shielded by its PS capsule against phagocytosis (26). The phenotype of pneumococci colonizing the nasopharynx, however, differs in several respects from that of pneumococci causing invasive disease, including reduced expression of capsular PS and increased expression of certain noncapsular antigens (27). Further elucidation of the role of T cells in defense against pneumococcal colonization will require an assessment of whether these T cells are responding to antigens from pneumococci that have been internalized by professional antigen-presenting cells and/or epithelial cells (28), as well as identification of the antigen(s) involved.

The precise mechanisms whereby CD4+ T cells may effect protection against colonization remain to be determined. One possibility is that the CD4+ T cells protect against pneumococcal colonization by generating a T helper 1 (Th1)-type response, a process similar to that shown to protect against “intracellular” bacteria such as Listeria, Salmonella, and mycobacteria (29, 30). Our previous finding that the preservation of a Toll-like receptor 4 ligand in the WCV is critical for protection (ref. 31 and R.M., unpublished data) is consistent with this hypothesis, because Toll-like receptor 4 ligands have been shown to bias toward T helper 1-type responses (32). Another potential mechanism, independent of T helper 1 or 2 profile, may be IL-17A-producing CD4+ T cells, which have been shown to mobilize neutrophils through granulopoeisis and chemokine induction (33). Recent data suggest that IL-17A release by these T cells depends on dendritic cells producing IL-23 through Toll-like receptor-dependent pathways (34).

Limited serotype coverage and cost restrict the usefulness of the oligovalent conjugated capsular vaccine for childhood disease prevention worldwide, and therefore more economical modes of immunization are urgently needed. It may be useful to evaluate vaccination strategies based on mechanisms of naturally acquired immunity to colonization and specifically based on the Ab-independent immunity demonstrated here. Vaccines that reduce carriage and induce herd immunity against pneumococcus, based on antigens shared among serotypes, may represent a viable strategy to reduce the burden of disease in both developed and developing countries. Despite the fact that the heptavalent PS conjugate vaccine offers only partial protection against a limited range of serotypes (24), it appears already to have prevented a substantial amount of disease by means of its indirect effects on transmission to nonvaccinated age groups (35); this experience suggests that a vaccine that offered better protection against carriage of a wider range of serotypes could have a major impact on disease, not only in those who are vaccinated but in other groups as well. A number of the noncapsular antigens have been proposed as vaccines, but have not yet been demonstrated to have efficacy in humans (36). We had previously shown that WCV has the ability to stimulate Ab responses to multiple antigens and that these Ab responses can protect against invasive disease (9). Here, we have shown that WCV additionally stimulates Ab-independent, CD4+ T cell-dependent immune responses that are protective against asymptomatic carriage. Furthermore, the WCV has properties that suggest excellent potential for developing countries: low cost, mucosal administration, and broad coverage. It will be of great interest also to see whether the WCV (given intranasally with a suitable mucosal adjuvant) will protect humans as well as mice against colonization.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Bloom, E. Kurt-Jones, J. Rengarajan, M. Starnbach, M. Swamy, A. Tzianabos, and M. Wessels for helpful discussions during the course of this work; M. Rojas-Lopez for assistance with flow cytometry; and Eddie Ades (Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta) and Susan Hollingshead (University of Alabama, Birmigham, AL) for providing recombinant protein antigens for ELISA. R.M. was supported by the Meningitis Research Foundation and National Institutes of Health Grant K08 AI51526-01. A.S. was supported by National Institutes of Health Training Grant AI07061-26. M.L., C.M.T., and K.T. were supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 5 R01 AI048935.

Author contributions: R.M., P.W.A., and M.L. designed research; R.M., K.T., A.S., C.M.T., and M.L. performed research; R.M., K.T., A.S., C.M.T., P.W.A., and M.L. analyzed data; and R.M. and M.L. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: β2m, β2-microglobulin; cfu, colony-forming units; CT, cholera toxin; PS, polysaccharide; WCV, whole-cell vaccine.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (1998) Weekly Epidemiol. Records 73, 187-188. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, S., Shinefield, H., Fireman, B., Lewis, E., Ray, P., Hansen, J. R., Elvin, L., Ensor, K. M., Hackell, J., Siber, G., et al. (2000) Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19, 187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eskola, J., Kilpi, T., Palmu, A., Jokinen, J., Haapakoski, J., Herva, E., Takala, A., Kayhty, H., Karma, P., Kohberger, R., et al. (2001) N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 403-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan, S. L., Mason, E. O., Jr., Wald, E. R., Schutze, G. E., Bradley, J. S., Tan, T. Q., Hoffman, J. A., Givner, L. B., Yogev, R. & Barson, W. J. (2004) Pediatrics 113, 443-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malley, R., Stack, A. M., Ferretti, M. L., Thompson, C. M. & Saladino, R. A. (1998) J. Infect. Dis. 178, 878-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dagan, R., Melamed, R., Muallem, M., Piglansky, L., Greenberg, D., Abramson, O., Mendelman, P. M., Bohidar, N. & Yagupsky, P. (1996) J. Infect. Dis. 174, 1271-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austrian, R. (1986) J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 18, Suppl. A, 35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipsitch, M., Whitney, C. G., Zell, E., Kaijalainen, T., Dagan, R. & Malley, R. (January 25, 2005) PLoS Med., 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Malley, R., Lipsitch, M., Stack, A., Saladino, R., Fleisher, G., Pelton, S., Thompson, C., Briles, D. E. & Anderson, P. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69, 4870-4873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malley, R., Morse, S. C., Leite, L. C. C., Mattos Areas, A. P., Ho, P. L., Kubrusly, F. S., Almeida, I. C. & Anderson, P. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72, 4290-4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCool, T. L. & Weiser, J. N. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72, 5807-5813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trzcinski, K., Thompson, C. M. & Lipsitch, M. (2003) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 7364-7370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitamura, D., Roes, J., Kuhn, R. & Rajewsky, K. (1991) Nature 350, 423-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zijlstra, M., Bix, M., Simister, N. E., Loring, J. M., Raulet, D. H. & Jaenisch, R. (1990) Nature 344, 742-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grusby, M. J., Auchincloss, H., Jr., Lee, R., Johnson, R. S., Spencer, J. P., Zijlstra, M., Jaenisch, R., Papaioannou, V. E. & Glimcher, L. H. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 3913-3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penttila, J. M., Anttila, M., Varkila, K., Puolakkainen, M., Sarvas, M., Makela, P. H. & Rautonen, N. (1999) Immunology 97, 490-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadioglu, A., Coward, W., Colston, M. J., Hewitt, C. R. & Andrew, P. W. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72, 2689-2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janeway, C. A., Travers, P., Walport, M. & Shlomchik, M. J. (2001) Immunobiology (Garland, New York).

- 19.Anderson, P., Pichichero, M. E. & Insel, R. A. (1985) J. Pediatr. 107, 346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahman, H., Kayhty, H., Lehtonen, H., Leroy, O., Froeschle, J. & Eskola, J. (1998) Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 17, 211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park, H. S., Costalonga, M., Reinhardt, R. L., Dombek, P. E., Jenkins, M. K. & Cleary, P. P. (2004) Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 2843-2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadioglu, A., Gingles, N. A., Grattan, K., Kerr, A., Mitchell, T. J. & Andrew, P. W. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 492-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lederman, H. M. & Winkelstein, J. A. (1985) Medicine (Baltimore) 64, 145-156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Brien, K. L. & Dagan, R. (2003) Vaccine 21, 1815-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapola, S., Jantti, V., Haikala, R., Syrjanen, R., Carlone, G. M., Sampson, J. S., Briles, D. E., Paton, J. C., Takala, A. K., Kilpi, T. M. & Kayhty, H. (2000) J. Infect. Dis. 182, 1146-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skov Sorensen, U. B., Blom, J., Birch-Andersen, A. & Henrichsen, J. (1988) Infect. Immun. 56, 1890-1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, J. O. & Weiser, J. N. (1998) J. Infect. Dis. 177, 368-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cundell, D. R., Gerard, N. P., Gerard, C., Idanpaan-Heikkila, I. & Tuomanen, E. I. (1995) Nature 377, 435-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geginat, G., Lalic, M., Kretschmar, M., Goebel, W., Hof, H., Palm, D. & Bubert, A. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 6046-6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Jong, R., Altare, F., Haagen, I. A., Elferink, D. G., Boer, T., van Breda Vriesman, P. J., Kabel, P. J., Draaisma, J. M., van Dissel, J. T., Kroon, F. P., et al. (1998) Science 280, 1435-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malley, R., Henneke, P., Morse, S. C., Cieslewicz, M. J., Lipsitch, M., Thompson, C. M., Kurt-Jones, E., Paton, J. C., Wessels, M. R. & Golenbock, D. T. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1966-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agrawal, S., Agrawal, A., Doughty, B., Gerwitz, A., Blenis, J., Van Dyke, T. & Pulendran, B. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 4984-4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolls, J. K. & Linden, A. (2004) Immunity 21, 467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Happel, K. I., Zheng, M., Young, E., Quinton, L. J., Lockhart, E., Ramsay, A. J., Shellito, J. E., Schurr, J. R., Bagby, G. J., Nelson, S. & Kolls, J. K. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 4432-4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitney, C. G., Farley, M. M., Hadler, J., Harrison, L. H., Bennett, N. M., Lynfield, R., Reingold, A., Cieslak, P. R., Pilishvili, T., Jackson, D., et al. (2003) N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1737-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Briles, D. E., Tart, R. C., Swiatlo, E., Dillard, J. P., Smith, P., Benton, K. A., Ralph, B. A., Brooks-Walter, A., Crain, M. J., Hollingshead, S. K. & McDaniel, L. S. (1998) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 645-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]