Abstract

Background

Multiple authors have reported that “general anesthesia”(GA), as a generic and uncharacterized therapy, is contraindicated for patients undergoing endovascular management of acute ischemic stroke(EMAIS). The recent AHA update cautiously suggests that it might be reasonable to favor conscious sedation over GA during EMAIS. We are concerned that such recommendations will result in patients undergoing endovascular treatment without consideration of the effects of specific anesthetic agents, anesthetic dose, nor appropriate critical consideration of the individual patient's issues. We hypothesized that significant variation in anesthetic practice comprises GA and that outcome differences among types of GA would arise.

Methods

With IRB approval we examined records of patients who underwent anterior circulation EMAIS at UPenn from 2010 to 2015. Patients were managed by different anesthesiologists with no specific protocol. We analyzed ASA status, NIHSS, type of stroke, procedure, different types of anesthetic, blood pressure control, and outcome metrics. Modified Rankin Scales(mRS) were determined from medical records.

Results

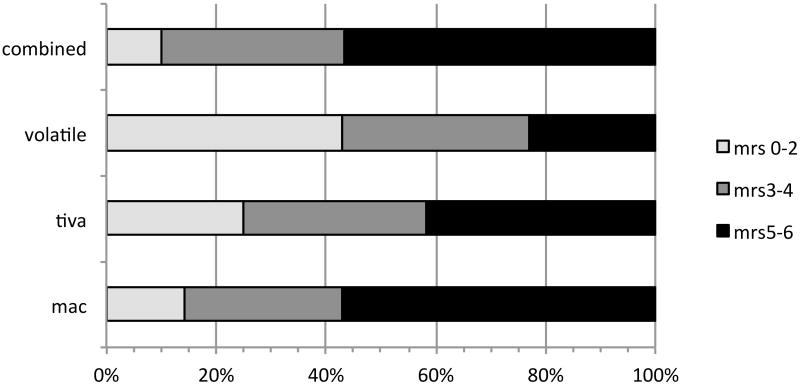

GA was used in 91% of patients. Several types of GA were employed: intravenous(TIVA), volatile, and intravenous/volatile(combined). mRS scores ≤2 at discharge were observed in 42.8% of our patients receiving volatile anesthesia and were better in patients receiving only volatile agents after induction of anesthesia (P<0.05).

Conclusion

Our data support the notion that anesthetic techniques and associated physiology used in EMAIS are not homogenous, making any statements about the effects of generic “GA” in stroke ambiguous. Moreover, our data suggest that the type of GA may affect outcome after EMAIS.

Keywords: Anesthesia, Neuroanesthesia, Stroke, Thrombectomy, Interventional radiology, endovascular management

Introduction

The primary treatment goal in acute ischemic stroke is to reperfuse the brain as quickly and as safely as possible. Endovascular stroke therapy is highly effective in revascularizing patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS). Recently, the MR CLEAN trial (Multicenter Randomized Clinical trial of Endovascular Treatment in the Netherlands)[1] showed significant improvement in primary and secondary outcomes with endovascular therapy compared to medical management. Van den Berg et al,[2] investigators in the MR CLEAN trial, published subset analyses on use of general anesthesia(GA) in endovascular management of AIS (EMAIS). Their data indicate that patients who had GA showed worse outcome with endovascular therapy whereas the local anesthesia cohort had improved outcome.

Based on multiple retrospective reports which do not report the specific elements of GA or attempt to adjust results based on NIHSS, authors are now advising to not routinely use GA, although without specific description, for EMAIS.[3, 4] Indeed, the recent update published by the American Heart Association[4] suggests that it might be reasonable to favor conscious sedation over general anesthesia during endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke but that prospective studies are warranted. Recommendations generally do acknowledge the non conclusive retrospective nature of the data. But we are concerned that non-individualized recommendations for the specific type of anesthesia (uncharacterized GA vs uncharacterized sedation) will result in patients undergoing endovascular thrombectomy without consideration of the specific effects of specific anesthetic agents, nor appropriate critical consideration of the individual patient's issues relevant to anesthesia choice.

The purpose of this report is to show the variation in anesthetic practice for EMAIS in our own institution and compare our results with recent EMAIS trials. Moreover, we test the hypothesis that subsets of anesthetic practice paradigms may impact on neurologic outcome after EMAIS. Lastly, given the ample published speculation regarding mechanisms of GA in worsening of outcome after EMAIS a secondary aim is to provide a brief overview of potentially important anesthetic effects which may influence outcome after EMAIS.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients who underwent endovascular treatment of anterior circulation, acute ischemic stroke at the University of Pennsylvania from January 2010 to March 2015. We included all patients who underwent endovascular treatment, including mechanical thrombectomy and/or intra-arterial TPA. We included patients who had intravenous tPA and endovascular therapy as well as those undergoing endovascular therapy alone. We excluded patients who only received intravenous TPA or angiogram. To assess potential impact of type of anesthesia exposure on outcome, we divided anesthesia type into 4 categories—(monitored anesthesia care(MAC) total intravenous anesthesia(TIVA), volatile anesthetics(VOL), and a combination of intravenous and volatile anesthetics(Comb). We measured clinical outcome by assigning patients a modified Rankin Score(mRS) at discharge. This was assigned by two blinded authors after examining discharge summaries and stroke attending notes. Patients who had complete recovery were assigned mRS 0-1, mild disability 2, moderate disability and transferred to rehabilitation 3, nursing home with severe disability 4, hospice/withdrawal of care 5-6.[5] Standard monitoring was employed for each patient including pulse oximetry, end-tidal CO2, O2, and anesthetic gas analysis, and electrocardiogram, Blood pressure was monitored in each patient by automated sphygmomanometer or by intra-arterial cannula, with efforts generally made to place an arterial cannula but without delaying the intervention.

Data collection

With IRB approval we examined records of patients who underwent anterior circulation EMAIS. Patients were managed by different anesthesiologists with no specific protocol. We analyzed ASA physical status, baseline NIHSS, type of stroke, procedure, types of anesthetics, BP control, and outcome metrics.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with descriptive statistics. Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviation or medians with interquartile range as appropriate. Categorical data are presented as counts with percentages. Univariate analysis of mRS scores by anesthesia type was performed with the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's test using the Bonferroni correction. Blood pressure values were compared between anesthesia types at baseline and various follow up time points using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by pairwise t-tests using the Bonferroni correction. A logistic regression model was built for mRS scores ≤2 to control for potential confounding. Variables with significant associations with outcome in univariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariable model. All analyses were conducted with Stata, version 12 (College Station, TX).

Results

84 patients were analyzed; 46 male, average age 66 ± 16 years. Demographics are in table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Males | 46(55) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age years mean (SD) | 66(16) |

|

| |

| Admission NIHSS | |

| NIHSS<10 | 5(6) |

| NIHSS 10-19 | 39(46) |

| NIHSS 20-29 | 37(44) |

| NIHSS>30 | 3(4) |

|

| |

| At Discharge: | |

| Average hospital day stay days mean (SD) | 13.0(9) |

| No. of patients with tracheostomy | 9(11) |

| No. of patients with peg | 23(27) |

Unless otherwise indicated data are N(%)

Specific anesthetic drugs

Our practice reflects the retrospective and uncontrolled nature of this report. Nonetheless there were distinct differences that allowed us to create groups for comparisons.

TIVA patients received a combination of propofol bolus and infusion (40-140mcg/kg/min) and fentanyl boluses . 92% of TIVA patients received a vasopressor.

MAC patients revealed no uniformity to anesthetic practice—four received fentanyl, one received remifentanil only, one received dexmedtomedine, one received propofol. 14 % of MAC patients received a vasopressor.

Volatile patients received <0.5 MAC (Minimum Alveolar Concentration) of desflurane (>80%) or sevoflurane(20%). 89% received a vasopressor.

Combined patients received propofol(30-140 mcg/kg/min) along with volatile agents at less than half a MAC. 90% received a vasopressor.

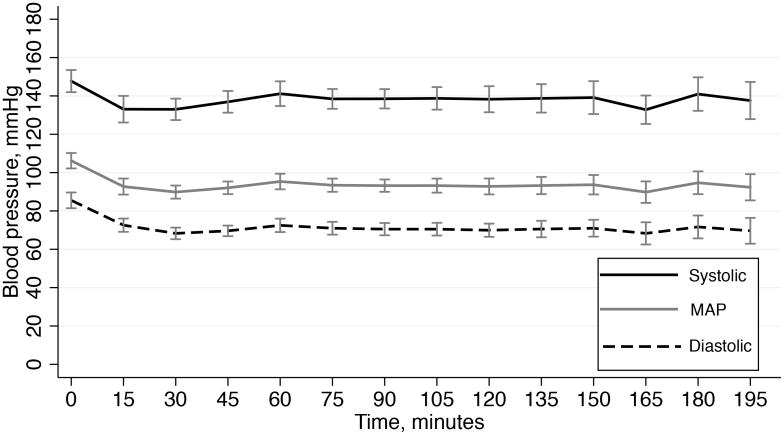

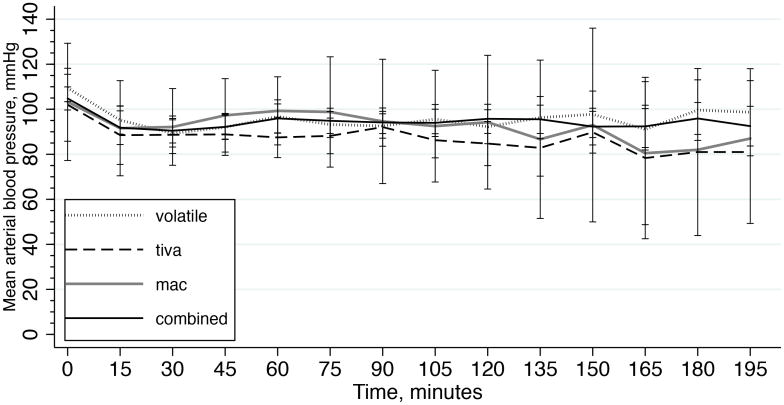

Of the entire cohort, 26% (22/84) had a mRS scale of 0-2 at discharge. 95% of these good outcome patients received GA and 5% received MAC. One patient in the MAC group had a mRS score less than 2. Several types of GA were employed (Table 2). Pre induction/intra procedure blood pressure monitoring by intra-arterial catheter among the groups was as follows: 35%/94% for combined, 34%/86% for volatile, 25%/92% for TIVA, and 50%/50% for MAC. The trend of blood pressures during the procedure is shown in Figure 1. The figure is notable for parallel trends in systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) over time. MAP values are further detailed in table 3. MAP values were similar across groups at baseline, and the change at 30 minutes and mean MAP during the procedure were also similar. The trend in MAP over time by group is shown in Figure 2. The use of vasopressor drugs to support blood pressure was common in the population, with the exception of the MAC group (Table 2). Of patients that received any vasopressor support, 55/70 (78.6%) received continuous infusions of either phenylephrine (n=50) or epinephrine (n=5). The remaining 15 patients received only bolus therapy with either phenylephrine (n=7) or ephedrine (n=8).

Table 2. Characteristics of Anesthesia Groups.

| MAC | TIVA | VOL | Comb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 7 | 12 | 35 | 30 |

| Male | 1(14.3) | 5(41.6) | 22(62.8) | 18(60) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 75.0 (11.4) | 69.8 (15.9) | 62.7 (17.2) | 66.5 (15.3) |

| HTN | 7(100) | 11(91.6) | 27(77.1) | 27(90) |

| DM | 2(28.5) | 5(41.6) | 9(25.7) | 7(23.3) |

| AFib | 5(71.4) | 7(58.3) | 20(57.1) | 17(56.6) |

| HL | 7(100) | 9(75) | 21(60) | 22(73.3) |

| Prior stroke/TIA | 1(14.2) | 2(16.6) | 4(11.4) | 7(23.3) |

| CAD | 6(85.7) | 9(75) | 21(60) | 21(70) |

| NIHSS, median (IQR) | 18 (16-22) | 21.5 (16-26) | 19 (13-22) | 19 (14-23) |

| Prox occl M1 | 4(57.1) | 6(50) | 19(54.2) | 14(46.6) |

| M2 occl | 2(28.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8(22.8) | 4(13.3) |

| ICA occl | 1(14.2) | 6(50) | 8(22.8) | 12(40) |

| Mech thromb | 5(71.4) | 10(83.3) | 30(85.7) | 26(86.6) |

| IA TPA | 0 | 7(58.3) | 13(37.1) | 10(33.3) |

| Combinationa | 0 | 5(41.6) | 10(28.5) | 9(30) |

| ASA PS score ≤ 3 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (33.3) | 13 (37.1) | 14 (46.7) |

| Any vasopressor support | 1 (14.3) | 11 (91.7) | 31 (88.6) | 27 (90.0) |

| Good Recovery mRS (0-2) | 1(14.3) | 3(25) | 15(42.9) | 3(10) |

Unless noted otherwise, data are N(%)

patients undergoing both mechanical thrombectomy and intra-arterial TPA

Abbreviations: HTN-hypertension; AFib-atrial fibrillation; med- median; IQR- interquartile range; IA-intraarterial; HL-hyperlipidemia; TIA-transient ischemic attack; CAD-coronary artery disease; NIHSS-NIH stroke scale; prox-proximal; occl-occlusion; mech thromb- mechanical thrombectomy; TPA-tissue plasminogen activator; ASA PS-American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status; mRS-modified Rankin Scale; MAC-monitored anesthesia care; TIVA; total intravenous anesthesia; VOL-volatile; Comb-Combined intravenous and volatile anesthesia

Figure 1.

Trend of blood pressure over time in all patients. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval for each measure at each time point.

Table 3. Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP).

| MAC | TIVA | VOL | Comb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| MAP | ||||

| Baselinea | 103.3 (28.1) | 102.0 (25.5) | 109.5 (17.7) | 104.8 (13.7) |

| Maximum* change over 1st 30 minutesb | -16.6 (7.6) | -19.0 (22.2) | -24.8 (17.8) | -19.2 (14.4) |

| Mean MAP during procedurec | 95.1 (16.2) | 89.0 (10.8) | 95.8 (12.2) | 94.3 (11.0) |

p=0.31

p=0.53

p=0.41

This value represents the maximum observed change in mean arterial blood pressure during the initial 30 minutes of the procedure.

Figure 2.

Trend of mean arterial blood pressure over time stratified by anesthesia type. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval for each measure at each time point. No significant differences were noted between groups across all time points.

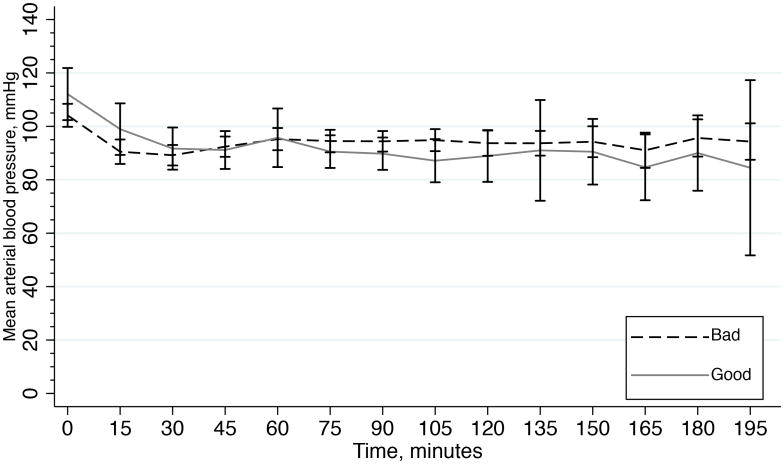

In univariate analysis mRS scores differed significantly across anesthesia type, with the best outcome and lowest mRS scores observed in patients that received only volatile agents after induction of anesthesia (P<0.05) (Figure 3). Other significant predictors of mRS score in univariate analysis were NIHSS and age. mRS was not associated with any blood pressure parameter (baseline, change at 30 minutes, or mean during procedure), p>0.05 for all comparisons. Trend in MAP stratified by outcome status is shown in Figure 4. . In addition, mRS was not associated with the use of vasopressor drugs to support blood pressure. Importantly, the high rate of vasopressor use in the population limits power to examine this relationship. Variables with significant univariate associations, along with anesthesia type were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. After adjusting for NIHSS and age, anesthesia type remained significantly associated with mRS score at discharge (Table 4). Further adjustment for any of the MAP parameters did not alter the results of the final regression model.

Figure 3.

Outcome metrics. Percentage of patients with mRS scores at discharge derived from the medical record, according to type of anesthesia. Scores were better in the group receiving volatile anesthesia after induction of anesthesia. (P<0.05)

Figure 4.

Trend of mean arterial blood pressure over time stratified by outcome. Good defined as mRS≤2; Bad defined as mRS>2. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval for each measure at each time point. No significant differences were noted between groups across all time points.

Table 4. Multivariable Logistic Regression Model for achieving mRS score ≤2 at discharge.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Anesthesia type* | 0.048 | ||

| Volatile | ref. | ||

| TIVAa | 0.69 | 0.13-3.77 | |

| MACb | 0.35 | 0.04-3.76 | |

| Combc | 0.15 | 0.04-0.66 | |

| Age | 0.96 | 0.93-0.99 | 0.044 |

| NIHSS | 0.87 | 0.79-0.96 | 0.010 |

Reference category for anesthesia type is volatile. Thus, odds ratios for the other anesthesia types are in reference to volatile. TIVA- total intravenous anesthesia; MAC- monitored anesthesia care; Comb-intravenous and volatile combined

Discussion

Two major conclusions of our evaluation of our institutional anesthesia practice for EMAIS are apparent: (1) Absent a specific protocol significant variation in anesthetic management can arise, and, (2) The type of general anesthetic used may affect outcome.

In a non-protocolized environment with anesthesia provided, often at night by in-house on-call non neuro-oriented anesthesiology teams, significant variation in anesthesia was observed but with reasonably tight control of blood pressure. John et al[6] also noted variation in a report of their use of conscious sedation. This suggests that reference to non-characterized generic “GA” or sedation as an element of EMAIS reports may be inappropriate and lead authors to invalid or ambiguous conclusions. Anesthesiologists evaluating such reports and faced with a patient in need of EMAIS are uncertain as to what is being recommended to be used or avoided. Future reports about management of EMAIS patients should address specific anesthetic and physiologic details. Notably, a proposed prospective investigation, the SIESTA trial, continues this pattern of studying uncharacterized GA without involvement of anesthesia teams or coinvestigators[7].

Our data indicate that the type of anesthesia employed may indeed be predictive or associated with outcome in EMAIS as the various available anesthetic techniques and drugs have disparate neurochemical, neurophysiologic, and systemic effects.[8, 9] Because of this concern we divided our retrospective dataset into four general categories of anesthesia: MAC, Volatile, TIVA, and combined intravenous and volatile. Even this division is potentially confusing There are multiple volatile agents that have some differences between them and there are multiple intravenous agents used in TIVA, which have disparate mechanisms and neurophysiologic effects. Moreover., there are even more differences related to nonlinear effects of depth of anesthesia on metabolism[8, 10] or dose-related potential neuroprotection/neurotoxicity[11]. Our data suggest that attention to the elements of GA matter. Indeed, we made the unexpected observation of improved outcome with the use of volatile anesthetics.

As with every retrospective study this observation is the hypothesis for a future prospective study. The sample size is rather small, the distribution of ICA occlusions was not homogeneous, we did not record TICI scores, which arguably may be affected by concurrent anesthetic, and assigning mRS scores based on the medical record has been criticized,[12] making comparison to other studies suspect but nonetheless likely useful within a single study. There is a potentially significant possibility that this finding of a favored technique is borne simply of chance or related to different demographics, stroke severity, or medical conditions. It would thus be inappropriate to advise any specific anesthesia practice based on our observations.

Anesthesia Issues

Our investigation raises important questions regarding what aspects of periprocedural management actually contributes to the end result Given the ample speculations in EMAIS reports on the potential mechanisms of impact of GA on outcome after EMAIS we will briefly review what is known and relevant to the ischemic brain about effects of the disparate anesthetic techniques that we employed in EMAIS.

ASA PS vs NIHSS

As NIHSS assesses stroke severity only and does not assess patients' overall medical well-being related to anesthesia outcome, its use could produce misleading conclusions when analyses use NIHSS to correct for severity of baseline illness in analyzing the effects of anesthesia on a neurologic process. This implies that using NIHSS as a measure to correct for baseline status in evaluating for effects of anesthesia as is done in many reports is suboptimal use of a scale for which is was not designed. ASA physical status assesses overall health and function of the person including cardiac and respiratory status and it incorporates non neurologic issues not included in the NIHSS. However, ASA physical status is imperfect also as it is low on details. Perhaps common ICU scoring systems such as APACHE (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation), MPM (mortality probability model), or SAPS (simplified acute physiology score) three major ICU scoring and risk adjustment systems in use [13, 14]would be more useful when stroke studies are correcting for the impact of systemic factors on anesthesia role in neurologic outcome. Anesthesia affects every organ in the body but NIHSS assesses only baseline neurologic function.

Blood Pressure Management

Blood pressure management is thought to be an essential element of EMAIS but most reports do not include blood pressure data. Given that GA clearly predisposes to lower BP, possibly contributing to bad outcome[15-17] this is certainly a valid area of concern. Conversely, John et al[6] noted worse outcome with GA in EMAIS, but detected no difference in blood pressure between sedation and GA. Takehashi et al[18] noted decreased BP with GA but no effect on outcome after EMAIS, and Jagani et al[16] reported significant BP effects of GA but did not observe a link between BP and outcome. One the other hand, Mundiyanapurath et al[19] maintained blood pressure but found an inverse association between amount of norepinephrine used and outcome. These observations provide a hint that the real issue is dose of anesthetic or sedative as higher GABAergic anesthetic dose, in general, may produce a greater decrement in BP and/or a higher pressor requirement. Conversely, anesthetic agents which do not decrease blood pressure so much, eg, opioids, ketamine, nitrous oxide, have neurotoxic potential, as discussed more below. But unfortunately, these reports on GA impact in EMAIS lack details on anesthetic drugs employed.

Notably, in our series a blood pressure effect between anesthetic or between outcome groups was not apparent. Notwithstanding the lack of a protocol this suggests a general appreciation among our anesthesiologists of the importance of blood pressure management during ischemic stroke. Indeed we may also be revealing the importance of having anesthesiologists involved in the management of these patients. It is noteworthy that such involvement of anesthesiologists is not included in the methods sections in many reports([2, 7, 17, 19]. Importantly, the report by Jagani et al [16] showing worse outcome with GA and lower BP indicates a large percentage of patients receiving volatile anesthesia, with nitrous oxide(potentially neurotoxic[11]) in 11% and propofol infusion in 11%. No subgroup analysis similar to what we report or description of anesthetic doses is provided. Our volatile anesthesia treated patients received doses expected to be amnestic but well below MAC, a dose which would typically be used for more invasive procedures. The end-tidal anesthetic concentration monitoring allows for precise titration of dose to end-organ concentration. Conversely, intravenous propofol infusions do not provide that capability and if not appropriately titrated to clinical signs of anesthetic depth, tend to develop progressively higher brain and blood concentrations over time[20] with expected adverse hemodynamic consequences. The report by Löwhagen Hendén [17] clearly indicates an association between GA and low BP and worse outcome, but, similar to many other reports, gives no details on the composition of GA nor whether there was anesthesiologist involvement. Overall, it is apparent that conclusive information is either absent or conflicting regarding the potential role of blood pressure and its relationship to anesthetic dose in observed effects of GA on outcome after EMAIS.

Anesthetic Drugs

A variety of anesthetic drugs were employed in our patients. Thus, some comment on the disparate neurologic effects of these drugs is relevant.

Volatile Anesthetic Agents

Inhaled anesthetic agents (e.g. isoflurane) have protean neurological effects. They enhance inhibitory synaptic transmission by enhancing GABA and glycine and concurrently inhibit excitatory NMDA-type glutamate and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, activation of two-pore domain K2P channels and leak K+ channels.[9]

In general, inhalational agents, in a dose related manner uncouple metabolism from cerebral blood flow(CBF), increasing CBF while reducing metabolic rate(CMR) in a nonlinear manner becoming more apparent with increasing dose.[9] Although deeper anesthesia might be predicted to be neuroprotective, preclinical studies suggest this may not be the case.[21] There is much discussion in EMAIS reports that volatile anesthetics induce cerebral vasodilation and risk an intracranial steal. The possibility of a steal has been suggested with carotid occlusion during carotid endarterectomy.[22] However, higher brain tissue pO2 was reported with volatile agents compared to intravenous anesthetics[23] supporting the notion that volatile anesthetic mediated vasodilation may be beneficial. Moreover, volatile agents used in the context of carotid endarterectomy decrease the threshold low CBF at which EEG changes arise, but with somewhat unexplainable differences between agents, nonetheless further supporting a potential contribution to neuroprotection during EMAIS.[24]

Intravenous anesthetic agents

Commonly used modern intravenous anesthetic agents in the United States include the GABAergic drugs propofol, barbiturates, etomidate, and benzodiazepines. Other IV drugs with different neurochemical mechanism include ketamine, opioids, and dexmedtomedine Thiopental is available only outside the US.

GABAergic drugs: propofol, thiopental, etomidate, and benzodiazepines

These drugs bind to the GABA receptor and increase conductivity to chloride ions leading to hyperpolarisation of cell membranes.[9] They decrease CBF coupled to decreased CMR[9] and can be expected to increase CBF to an ischemic area. Barbiturate neuroprotection was reported in the context of focal temporary ischemia in a subhuman primate model.[25] The similarity of this to EMAIS suggests barbiturates or propofol should be helpful in EMAIS. However, the lower brain pO2 relative to volatile agents[23] and our results suggest otherwise.

Opioids

Commonly used anesthetic opioids act predominantly on μ-receptors.[8, 9] Effects on CMR and CBF are variable, dose dependent, and affected by other background anesthetics. Hemodynamically, they can cause bradycardia but with minimal potential for hypotension. No neuroprotection has been reported with opioids although at high but clinically relevant doses in rodents they produce limbic seizure, hypermetabolism, and brain damage with congruent neurometabolic effects in humans

Summary/Conclusions

Overall, this summary of anesthetic effects and our data indicates that anesthetics can increase or decrease CBF and CMR and confer both neuroprotection and neurotoxicity. Given that reports of GA worsening outcome in EMAIS do not describe the specific anesthetics involved or doses; and that our data suggest anesthetic techniques and drugs employed are heterogeneous and may affect outcome in a drug-specific manner; we believe that current data provide inadequate guidance for stroke teams, including the anesthesiologists, regarding specific choice of sedation or general anesthetic drugs to use during EMAIS. Our retrospective data suggest that when GA is selected maintenance with volatile anesthetics alone may be associated with improved outcome, but this requires prospective confirmation.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, grant number 1F32HL124914-01 through support of Dr Miano

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement: None of the authors declare any competing interests

- Made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, and r interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Provided final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

- Made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; and interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Provided critical insights in the drafting of the manuscript for important intellectual content; AND

- Provided final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

- Made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Provided critical insights in the drafting of the manuscript for important intellectual content AND

- Provided final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

- Made substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Participated in drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Provided final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

- Made substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Participated in drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Provided final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

- Made substantial contributions to the conception of the work; and interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Participated in drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Provided final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

- Made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, and interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Provided final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Contributor Information

Chitra Sivasankar, Instructor, Neuroanesthesiology Fellow, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Michael Stiefel, Director, Neurovascular Institute, Chief, Neurovascular Surgery, Director, Cerebrovascular & Endovascular Neurosurgery, Co-Director, Neurocritical Care, WestChester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY10595.

Todd A. Miano, Pharmacoepidemiology Research Fellow, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Guy Kositratna, Visiting Scholar, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Sukanya Yandrawatthana, Visiting Scholar, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania,Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Robert Hurst, Professor, Departments of Radiology, Neurosurgery, and Neurology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

W Andrew Kofke, Professor, Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical Care and Neurosurgery, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, 215-662-3774, Fax 215-615-3898.

References

- 1.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PSS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(1):11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Berg LA, Koelman DLH, Berkhemer OA, et al. Type of Anesthesia and Differences in Clinical Outcome After Intra-Arterial Treatment for Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2015 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grotta JC, Hacke W. Stroke Neurologist's Perspective on the New Endovascular Trials. Stroke. 2015 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, et al. 2015 AHA/ASA Focused Update of the 2013 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Regarding Endovascular Treatment: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association /American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasner SE. Clinical interpretation and use of stroke scales. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(7):603–12. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John S, Thebo U, Gomes J, et al. Intra-Arterial Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke Under General Anesthesia versus Monitored Anesthesia Care. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2014:262–7. doi: 10.1159/000368216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schönenberger S, Möhlenbruch M, Pfaff J, et al. Sedation vs. Intubation for Endovascular Stroke TreAtment (SIESTA) – a randomized monocentric trial. International Journal of Stroke. 2015;10(6):969–78. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown EN, Purdon PL, Van Dort CJ. General anesthesia and altered states of arousal: A systems neuroscience analysis. ANNU REV NEUROSCI. 2011:601–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sloan TB. Anesthetics and the brain. Anesthesiology Clinics of North America. 2002;20(2):265–92. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(01)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stullken EH, Jr, Milde JH, Michenfelder JD, et al. The nonlinear responses of cerebral metabolism to low concentrations of halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, and thiopental. Anesthesiology. 1977;46(1):28–34. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic S, Mennerick S, et al. Nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is an NMDA antagonist, neuroprotectant and neurotoxin. Nature Med. 1998;4(4):460–3. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinn TJ, Ray G, Atula S, et al. Deriving Modified Rankin Scores From Medical Case-Records. Stroke. 2008;39(12):3421–3. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.519306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslow MJ, Badawi O. Severity scoring in the critically ill: Part 2: Maximizing value from outcome prediction scoring systems. Chest. 2012;141(2):518–27. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslow MJ, Badawi O. Severity scoring in the critically ill: Part 1 - Interpretation and accuracy of outcome prediction scoring systems. Chest. 2012;141(1):245–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis MJ, Menon BK, Baghirzada LB, et al. Anesthetic management and outcome in patients during endovascular therapy for acute stroke. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(2):396–405. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318242a5d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jagani M, Brinjikji W, Rabinstein AA, et al. Hemodynamics during anesthesia for intra-arterial therapy of acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Löwhagen Hendén P, Rentzos A, Karlsson JE, et al. Hypotension During Endovascular Treatment of Ischemic Stroke Is a Risk Factor for Poor Neurological Outcome. Stroke. 2015;46(9):2678–80. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi CE, Brambrink AM, Aziz MF, et al. Association of intraprocedural blood pressure and end tidal carbon dioxide with outcome after acute stroke intervention. Neurocritical Care. 2014;20(2):202–8. doi: 10.1007/s12028-013-9921-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mundiyanapurath S, Stehr A, Wolf M, et al. Pulmonary and circulatory parameter guided anesthesia in patients with ischemic stroke undergoing endovascular recanalization. Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schüttler J, Ihmsen H. Population pharmacokinetics of propofol: A multicenter study. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(3):727–38. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200003000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warner D, Takaoka S, Wu B, et al. Electroencephalographic burst suppression is not required to elicit maximal neuroprotection from pentobarbital in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Anesthesiology. 1996;84(6):1475–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199606000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCulloch TJ, Thompson CL, Turner MJ. A randomized crossover comparison of the effects of propofol and sevoflurane on cerebral hemodynamics during carotid endarterectomy. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(1):56–64. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman WE, Charbel FT, Edelman G, et al. Thiopental and desflurane treatment for brain protection. Neurosurgery. 1998;43(5):1050–3. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199811000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michenfelder J, Sundt T, Fode N, et al. Isoflurane when compared to enflurane and halothane decreases the frequency of cerebral ischemia during carotid endarterectomy. Anesthesiology. 1987;67:336. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198709000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selman W, Spetzler R, Roessmann U, et al. Barbiturate-induced coma therapy for focal cerebral ischemia. Effect after temporary and permanent MCA occlusion. Journal of neurosurgery. 1981;55:220. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.2.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]