Abstract

Objectives

Our objective was to examine the relationship between residential proximity to agricultural fumigant use and neurodevelopment in 7-year old children.

Methods

Participants were living in the agricultural Salinas Valley, California and enrolled in the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children Of Salinas (CHAMACOS) study. We administered the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th Edition) to assess cognition and the Behavioral Assessment System for Children (2nd Edition) to assess behavior. We estimated agricultural fumigant use within 3, 5 and 8 km of residences during pregnancy and from birth to age 7 using California’s Pesticide Use Report data. We evaluated the association between prenatal (n=285) and postnatal (n=255) residential proximity to agricultural use of methyl bromide, chloropicrin, metam sodium and 1,3-dichloropropene with neurodevelopment.

Results

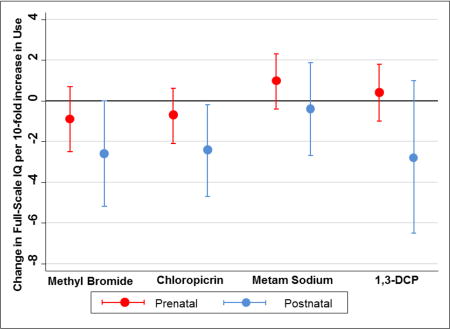

We observed decreases of 2.6 points (95% Confidence Interval (CI): −5.2, 0.0) and 2.4 points (95% CI: −4.7, −0.2) in Full-Scale intelligence quotient for each ten-fold increase in methyl bromide and chloropicrin use within 8 km of the child’s residences from birth to 7-years of age, respectively. There were no associations between residential proximity to use of other fumigants and cognition or proximity to use of any fumigant and hyperactivity or attention problems. These findings should be explored in larger studies.

Keywords: Behavior, Children, Fumigants, Neurodevelopment, Pesticides

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Methyl bromide, chloropicrin, metam sodium and 1, 3-dichloropropene (1,3-DCP) are common agricultural fumigants used primarily to reduce pathogens and pests in soil prior to planting crops. Approximately 44 – 51 million kilograms (kg) of these four fumigants are applied annually in the United States (Grube et al., 2011), and 13 million kg are applied annually in California (CDPR, 2016), constituting one sixth of all pesticide use in California. Fumigants are more likely than other pesticides to drift from application sites due to their high vapor pressure (California Department of Pesticide Regulation, 2015, 2016a, b). In 2012, California implemented a pesticide air monitoring network in several agricultural communities. Fumigants were frequently detected at each of the air monitoring sites, indicating repeated, low-level community exposures (CDPR, 2014). Acute human exposure to methyl bromide has produced symptoms including headaches, seizures, muscle weakness, memory problems (Bishop, 1992; Reidy et al., 1994), and neuropathy (Ben Slamia et al., 2006; Cavalleri et al., 1995). More attention and concentration problems have been reported in workers exposed to methyl bromide (Magnavita, 2009). Residents exposed to metam sodium after a train spill experienced increased psychological problems (e.g., depression and anxiety) (Bowler et al., 1994b). Symptoms of chloropicrin intoxication are also primarily neurologic, including tremors and seizures (TeSlaa et al., 1986). Although there is no evidence of neurotoxicity from limited human and animal research of 1,3-DCP (ATSDR, 2008), increased use of 1,3-DCP as a replacement for methyl bromide warrants further studies on the human health effects of this fumigant. A survey of pesticide related illnesses reported in 11 states from 1998 – 2006 found that soil applications of fumigants were responsible for the largest percentage of acute illnesses (45%) and non-occupational cases (61%) (Lee et al., 2011). In a risk assessment using California air monitoring data, these four high-use fumigants (methyl bromide, chloropicrin, metam sodium and 1,3-DCP) were the top four pesticides ranked in terms of chronic health risks and an estimated 5 million U.S. residents live in areas of high agricultural fumigant use (Lee et al., 2002).

Currently, there are no reliable biomarkers to assess human exposure to fumigants in epidemiologic studies (Hustinx et al., 1993; Magnavita, 2009; Verberk et al., 1979). Thus, residential proximity to fumigant use is currently the best method to characterize potential exposure. Since 1990, California has maintained a Pesticide Use Reporting (PUR) system which requires commercial growers to report all agricultural pesticide use to a one square mile (∼259 hectares) area (CDPR, 2016). A study using PUR data showed that methyl bromide use within a 7 × 7 square mile area (∼8 kilometer radius) around monitoring sites explained 95% of the variance in methyl bromide air concentrations, indicating a direct relationship between nearby agricultural use and potential community exposure (Li et al., 2005). Several epidemiologic studies have used PUR data and observed associations between higher nearby agricultural pesticide use during pregnancy and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes including birth defects (Carmichael et al., 2014; Rull et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2014), autism (Roberts et al., 2007; Shelton et al., 2014) and cognitive function (Gunier et al., 2016; Rowe et al., 2016).

We previously found that living within 5 km of methyl bromide use in the second trimester of pregnancy was associated with decreased birth weight, length, and head circumference (Gemmill et al., 2013). Methyl bromide was banned by the Montreal Protocol due to harmful effects on the ozone layer and is currently being phased out of use, resulting in increased usage of chloropicrin, metam sodium and 1,3-DCP in recent years (CDPR, 2016). In the present study, we investigate associations between residential proximity to agricultural use of four fumigants during the prenatal and postnatal periods and child neurodevelopment and behavior at age 7 in children participating in the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS), a longitudinal birth cohort study of primarily low-income Latino families living in the agricultural community of the Salinas Valley, California.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

We enrolled 601 pregnant women between October 1999 and October 2000 as part of the CHAMACOS study. Women were eligible if they were ≥ 18 years of age, <20 weeks gestation, eligible for California’s subsidized low-income prenatal health care, spoke English or Spanish, and were planning to deliver at the county hospital. We followed the women through the delivery of 537 live born children. We excluded children with medical conditions that could affect neurodevelopmental assessment (n=4, one child each with Downs syndrome, autism, deafness, and hydrocephalus). We included children who had a neurodevelopmental assessment at age 7 (n=336) and excluded two participants who did not have prenatal measurements of dialkyl phosphate (DAP) metabolites of organophosphate pesticides (OPs) because a previous analysis in this cohort found that DAPs were associated with neurodevelopment (Bouchard et al., 2011). For analyses of proximity to fumigant use, we included participants whose residential location was known for at least 80% of the time during pregnancy (n=285) for the prenatal period and from birth to the 7-year neurodevelopmental assessment (n=255) for the postnatal period. Written informed consent was obtained from all women and oral assent from all children at age 7; all research was approved by the University of California, Berkeley, Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects prior to commencement of the study.

2.2 Maternal interviews and assessments

Bilingual interviewers conducted maternal interviews in Spanish or English twice during pregnancy (∼13 and 26 weeks gestation), after delivery and when the children were 6 months and 1, 2, 3.5, 5 and 7-years of age. Interviews obtained demographic information including maternal age, education, country of birth, number of years lived in the United States, marital status, paternal education, and family income. We collected residential history information by asking participants if they had moved since the last interview and, if so, the dates of all moves. We conducted home visits shortly after enrollment (∼16 weeks gestation) and when the child was 6 months and 1, 2, 3.5 and 5-years of age. For each visit, latitude and longitude coordinates of the participant’s home were determined using a handheld global positioning system unit.

Mothers were administered the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) for English speakers or the Test de Vocabulario en Imagenes Peabody (TVIP) for Spanish speakers at the six-month visit to assess verbal intelligence (Dunn and Dunn, 1981). If maternal PPVT or TVIP scores were unavailable from the 6-month visit, we used scores from the re-administration of the test conducted at a 9-year visit (n=5) or assigned the mean score of the sample (n=2). A short version of the HOME (Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment) inventory was completed during the 7-year visit (Caldwell and Bradley, 1984).

2.3 Cognitive and behavior assessments

We assessed cognitive abilities when the children were 7-years of age using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th edition (WISC-IV) (Wechsler, 2003). All assessments were completed by a single bilingual psychometrician, who was trained and supervised by a pediatric neuropsychologist. Index scores for four domains were calculated based on the following subtests: Verbal Comprehension (composed of Vocabulary and Similarities subtests), Perceptual Reasoning (Block Design and Matrix Reasoning subtests), Working Memory (Digit Span and Letter-Number Sequencing subtests), and Processing Speed (Coding and Symbol Search subtests). We administered all subtests in the dominant language of the child using either the WISC-IV English or Spanish edition, which was determined through administration of the oral vocabulary subtest of the Woodcock–Johnson/Woodcock–Munoz Tests of Cognitive Ability (Woodcock and Munoz-Sandoval, 1990) in both English and Spanish at the beginning of the assessment as recommended in the WISC-IV Spanish Manual. The psychometrician was blinded to exposure status. We standardized WISC-IV scores against U.S. population–based norms for the English and Spanish versions of WISC-IV. We did not administer Letter-Number Sequencing or Symbol Search subtests for the first 3 months of assessments, therefore 27 participants lack scores for Processing Speed and Working Memory domains. A Full-Scale IQ was available for 255 children.

Children's behavior was assessed by maternal and teacher report at age 7 using the Behavior Assessment System for Children 2 (BASC-2) (Reynolds, 2004). The behavior assessments were interviewer-administered to the mother (due to low literacy rates) and self-administered by the child's teacher. The BASC-2 has been validated in English and Spanish. The BASC-2 Parent Rating Scale asks how often the child exhibits certain behaviors in the home setting (160 questions), while the Teacher Rating Scale asks about similar behaviors at school (139 questions). Scales of interest from the BASC-2 were hyperactivity and attention problems. Standardized T-scores were computed using age-standardized national norms, with higher values indicating more frequent problem behaviors.

2.4 Geographic-based estimates of agricultural fumigant use

To characterize potential exposure, we estimated agricultural fumigant use near each participant’s residence during the prenatal (entire pregnancy) and postnatal (birth to 7-year assessment) time periods using California PUR data from 1999–2008 (CDPR, 2016). We focused on methyl bromide, chloropicrin, metam sodium, and 1,3-DCP because they were the most commonly used agricultural fumigants (in kg applied) in our study area (Monterey County) during our study period (1999 – 2008). The PUR data included the amount (kg) of active ingredient applied, application date, location to a one-square mile section (1.6 km × 1.6 km) defined by the United States (U.S.) Public Land Survey System (PLSS). We edited the PUR data to correct for likely outliers that had unusually high application rates by replacing the amount of pesticide applied using the acres treated and the median application rate for that pesticide and crop combination (Gunier et al., 2001). Detailed descriptions of the equations and methods that we used to calculate nearby pesticide use have been published previously (Gunier et al., 2011).

For each participant, we estimated the amount of each fumigant used within 3, 5 and 8 km radii of residences during prenatal and postnatal periods using the latitude and longitude coordinates and a geographic information system. In all cases, the buffers around the homes included more than one PLSS section; therefore, we weighted the amount of pesticide applied in each section by the proportion of land area that was included in the buffer. We selected buffer distances of 3, 5 and 8 km for this analysis because these best capture the spatial scale of fumigant use most strongly correlated with measured fumigant concentrations in outdoor air samples (California Department of Pesticide Regulation, 2015; Li et al., 2005). To account for dispersion of fumigants from the application site, we summarized wind direction during the seven days (Cryer and van Wesenbeeck, 2011; Gao et al., 2013) after the application date using available wind direction data (CDWR, 2016), determined the direction of the residence relative to the PLSS section using GIS, and weighted fumigant use in each section by the proportion of time that the residence was downwind of Sections where fumigant applications occurred.

2.5 Data analysis

We log10-transformed continuous prenatal and postnatal fumigant use (kg/year) variables to reduce heteroscedasticity and the influence of outliers. We added one kg/year to the use prior to transforming so that the minimum log10 of use would be zero and all values would be positive. Scores for cognition and behavior were approximately normally distributed and were modeled as continuous outcomes. We used generalized additive models (GAMs) with a three-degrees-of-freedom cubic spline function to test for non-linearity. None of the digression from linearity tests were significant (p<0.2), therefore we expressed fumigant use linearly (on the log10 scale) in separate multivariable linear regression models for each fumigant. Regression coefficients thus represent mean change in cognition or behavior scores for each ten-fold increase in fumigant use.

We selected model covariates a priori based on factors associated with child neurodevelopment in previous analyses [i.e., child’s exact age at assessment, sex, maternal country of birth (Mexico vs. other) and HOME score at the 7-year visit (continuous)] (Bouchard et al., 2011; Gunier et al., 2016). We considered the following variables as additional covariates in our models: maternal age at delivery, maternal PPVT score (continuous), maternal education (≤ 6th grade vs. ≥ 7th grade), marital status at enrollment, and using the Centers of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) maternal depression (≥16 on CES-D) at the child’s 7-year visit (Davila et al., 2009). In addition, we considered covariates collected at each visit including housing density (number of persons per room), household poverty (<federal poverty level vs. ≥ federal poverty level) (Census, 2008), presence of father in the home (yes/no), maternal work status, location of neurodevelopmental assessment (field office or participant’s home), and season of assessment. We imputed missing values (<10% missing) at a visit point using data from the nearest available visit. We evaluated the average of DAP metabolites of OP insecticides measured in maternal urine samples (Bradman et al., 2005) collected during prenatal interviews at 13 weeks and 26 weeks gestation (n=283) in all models since these metabolite levels were related to Full-scale IQ in a previous study of this cohort (Bouchard et al., 2011). We also evaluated agricultural use of OP insecticides within 1 km of the residence during pregnancy in all models because this was related to IQ in a recently published study in this cohort (Gunier et al., 2016). We retained covariates that were significant (p < 0.2) in the final multivariate regression models. We included child age, sex, maternal country of birth, HOME score at the 7-year interview, prenatal DAPs and agricultural use of organophosphates within 1 km of the residence during pregnancy in all models. We included maternal depression in all models except for those assessing BASC-2 teacher reports because we believed maternal depression could affect maternal rating of child behavior or cognitive performance of the child. In models for cognition, we also included language of assessment, maternal education, maternal intelligence (PPVT) and household poverty level from the 7-year interview.

In separate sensitivity analyses, we controlled for exposure to other neurotoxicants, which we have previously found to be related to child IQ or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in our cohort adjusting for the same covariates listed above (Eskenazi et al., 2013; Gaspar et al., 2015; Marks et al., 2010), including log10-transformed lipid-adjusted concentrations (ng/g-lipid) of p, p’-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethylene (DDT), p, p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloro-ethylene (DDE) (n=219) (Bradman et al., 2007) and polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants (PBDEs) (n=221) measured in prenatal maternal blood samples (Castorina et al., 2011). We used the sum of the four major congeners (BDE-47, −99, −100, and −153) to estimate PBDE exposure (Eskenazi et al., 2013). In other sensitivity analyses, we excluded outliers identified with studentized residuals greater than three. To control for potential selection bias due to loss to follow-up, we ran regression models with weights determined as the inverse probability of inclusion in our analyses (Hogan and Lancaster, 2004). We determined probability of inclusion using multiple logistic regression models with baseline covariates as potential predictors. Since we evaluated many combinations of fumigants (4), buffer distances (3), time periods (2) and outcomes (3), we assessed adjustment for multiple comparisons to control for type 1 error rate using the Benjamani-Hochberg false discovery rate at p<0.05 (Hochberg and Benjamini, 1990). Finally to assess the effect of methyl bromide and chloropicrin, two fumigants with highly correlated use, in the same model, we calculated the residuals from a regression model with one fumigant as the dependent variable and the other as the independent variable. We then included these residuals as an uncorrelated proxy for exposure in a multivariate model with the fumigant that was the independent variable (Mostofsky et al., 2012). Similarly, we assessed the effect of postnatal fumigant use while controlling for highly correlated prenatal use by calculating residuals from a regression model with postnatal fumigant use as the dependent variable and prenatal use as the independent variable and including the residuals from this model in a multivariate model with prenatal fumigant use.

3. Results

3.1 Demographics, fumigant use and neurodevelopmental scores

Most mothers were born in Mexico (88%), under 30 years of age at delivery (73%) and married or living as married (85%) at the time of enrollment (Table 1). Almost half of the mothers (46%) and most fathers (52%) had a 6th grade education or less, and most families (72%) were living below the poverty level at the time of the 7-year visit. (United States Bureau of the Census, 2008) Slightly more than half of the children were girls (54%) and most children completed their WISC-IV assessment in Spanish (68%). Mothers included in our analyses (n=285) were older at delivery (27 vs. 25 years old), more likely to be Latina (99% vs. 94%) and married (83% vs. 77%), and were less likely to smoke (4% vs. 8%) than mothers with liveborn children that were not included in our analyses (n=252); otherwise the two populations were demographically similar.

Table 1.

CHAMACOS study cohort characteristics (n=285).1

| Cohort Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal Country of Birth | |

| Mexico | 251 (88%) |

| United States and other | 34 (12%) |

| Maternal Age at Delivery | |

| 18 – 24 | 109 (38%) |

| 25 – 29 | 99 (35%) |

| 30 – 34 | 49 (17%) |

| 35 – 45 | 28 (10%) |

| Maternal Education | |

| ≤ 6th grade | 132 (46%) |

| 7th grade or more | 153 (54%) |

| Marital Status at Enrollment | |

| Married/Living as married | 241 (85%) |

| Not married | 44 (15%) |

| Paternal Education | |

| ≤ 6th grade | 131 (52%) |

| 7th grade or more | 119 (48%) |

| Family Income at 7y visit | |

| ≤ Poverty level2 | 205 (72%) |

| > Poverty level2 | 80 (28%) |

| Maternal Depression at 7y Visit | |

| Yes | 79 (28%) |

| No | 206 (72%) |

| Sex | |

| Girl | 153 (54%) |

| Boy | 132 (46%) |

| Language of WISC-IV tests | |

| Spanish | 193 (68%) |

| English | 92 (32%) |

Included in analyses for prenatal fumigant use.

Poverty thresholds for 2008. (Census, 2008)

The most heavily used fumigants within 8 km of children’s residences during both the prenatal and postnatal periods were methyl bromide and chloropicrin, with mean ± SD postnatal wind-adjusted use of 89,200 kg ± 59,800 and 97,800 kg ± 67,700, respectively (Table 2). The distributions of WISC-IV and BASC-2 T-scores at 7-years of age are also presented in Table 2. The mean ± SD was 104 ± 14 for Full-scale IQ and similar for the subscales, except for Working Memory which was 93 ± 13. The mean ± SD BASC-2 T-scores for both parent and teacher report of attention and hyperactivity were all around 50 ± 10.

Table 2.

Distributions of wind-weighted agricultural fumigant use (kg) within 8-km of residence and neurodevelopmental assessment scores at 7-years of age.

| N | Mean ± SD | 25th | 50th | 75th | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal1 pesticide use (kg) | ||||||

| Methyl bromide | 285 | 13,400 ± 10,900 | 2,350 | 13,600 | 21,100 | 56,400 |

| Chloropicrin | 285 | 8,690 ± 7,120 | 1,210 | 8,690 | 13,800 | 35,000 |

| Metam sodium | 285 | 525 ± 1,500 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 8,640 |

| 1,3-DCP | 285 | 914 ± 1,810 | 5 | 52 | 806 | 8,230 |

| Postnatal2 pesticide use (kg) | ||||||

| Methyl bromide | 255 | 89,200± 59,800 | 20,500 | 111,000 | 136,000 | 349,000 |

| Chloropicrin | 255 | 97,800 ±67,700 | 10,600 | 128,000 | 152,000 | 287,000 |

| Metam sodium | 255 | 9,940 ± 9,440 | 1,180 | 5,240 | 21,400 | 54,600 |

| 1,3-DCP | 255 | 60,200 ±45,100 | 17,500 | 60,300 | 99,200 | 154,000 |

| WISC-IV | ||||||

| Full-scale IQ | 257 | 104 ± 14 | 92 | 105 | 114 | 144 |

| Perceptual Reasoning | 285 | 103 ± 16 | 92 | 100 | 112 | 141 |

| Processing Speed | 258 | 109 ± 13 | 100 | 109 | 118 | 136 |

| Verbal Comprehension | 285 | 107 ± 17 | 95 | 108 | 121 | 152 |

| Working Memory | 258 | 93 ± 13 | 83 | 91 | 99 | 132 |

| BASC-2 Parent Report3 | ||||||

| Attention | 284 | 50 ± 11 | 42 | 50 | 59 | 78 |

| Hyperactivity | 284 | 46 ± 9 | 40 | 44 | 50 | 79 |

| BASC-2 Teacher Report3 | ||||||

| Attention | 234 | 51 ± 8 | 45 | 51 | 56 | 69 |

| Hyperactivity | 234 | 49 ± 10 | 41 | 47 | 55 | 86 |

Prenatal period during pregnancy (1999 – 2001).

Postnatal period from birth to 7-year visit (2000 – 2008).

BASC-2 general sex combined T-scores.

Abbreviation: 1,3-DCP=1,3-dichloropropene.

3.2 Correlation of fumigant use

Agricultural fumigant use (log10-transformed) was moderately to highly correlated (p<0.001) at the three buffer distances we evaluated (Table 3). There was moderate to high correlation between postnatal fumigant use within 3 and 5 km (0.54 – 0.9), moderate to high correlation between fumigant use within 3 and 8 km (0.23 – 0.84) and high correlation between use within 5 and 8 km (0.78 – 0.99). Correlations were similar for prenatal fumigant use at different buffer distances (data not shown). Correlation was relatively high between prenatal and postnatal time periods for individual fumigants. For use within 8 km of residences, there was high correlation (p<0.001) between prenatal and postnatal use for chloropicrin (r=0.82) and methyl bromide (r=0.82), but no correlation for metam sodium and a negative correlation (r= −0.47) for 1,3-DCP. There was weak to high correlation (p<0.05) between the use of different fumigants. Postnatal use of metam sodium was weakly correlated with methyl bromide and chloropicrin (0.15 – 0.22), there was moderate correlation between 1,3-DCP and the other three fumigants (0.56 – 0.73), while methyl bromide and chloropicrin use was highly correlated (0.96).

Table 3.

Pearson correlations of log-transformed agricultural fumigant use (kg) by distance, time period and active ingredients.

| Comparison | N | Methyl Bromide |

Chloropicrin | Metam Sodium |

1,3-DCP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlations by distance | |||||

| Postnatal 3 and 5 km | 255 | 0.86** | 0.90** | 0.54** | 0.74** |

| Postnatal 3 and 8 km | 255 | 0.79** | 0.84** | 0.23** | 0.47** |

| Postnatal 5 and 8 km | 255 | 0.99** | 0.97** | 0.73** | 0.86** |

| Correlations by time period | |||||

| Prenatal and Postnatal 8 km | 255 | 0.82** | 0.82** | -0.01 | -0.47** |

| Correlations between fumigants | |||||

| Methyl Bromide Postnatal 8 km | 255 | - | - | - | - |

| Chloropicrin Postnatal 8 km | 255 | 0.96** | - | - | - |

| Metam Sodium Postnatal 8 km | 255 | 0.15* | 0.22** | - | - |

| 1,3-DCP Postnatal 8 km | 255 | 0.68** | 0.73** | 0.56** | - |

p<0.05;

p<0.001;

Abbreviation: 1,3-DCP=1,3-dichloropropene.

3.3 Fumigant use and neurodevelopment

Table 4 shows the associations of wind-adjusted prenatal and postnatal fumigant use within 8 km of the home and IQ (associations within 3 and 5 km are shown in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). There were no significant relationships between wind-adjusted prenatal fumigant use within 5 or 8 km and Full-Scale IQ or any of the WISC-IV subscales (Table 4 and Supplemental Table S1). However, we observed some associations between prenatal fumigant use within 3 km and IQ. Specifically, a ten-fold increase in wind-adjusted prenatal methyl bromide use within 3 km (Supplemental Table S1) was marginally associated with lower Full-scale IQ (β=−1.3; 95% CI: −2.7, 0.1), and reduced Processing Speed [β=−1.5; 95% confidence interval (CI): −2.9, −0.2], while a ten-fold increase in prenatal chloropicrin use within 3 km was marginally associated with a lower Processing Speed (β=−1.4; 95% CI: −2.8, 0.1).

Table 4.

Adjusted* association between a ten-fold increase in wind-adjusted fumigant use (kg) within 8-km of residence and 7-year WISC Scales.

| Full-Scale IQ | Verbal Comprehension |

Working Memory | Perceptual Reasoning |

Processing Speed | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| N | β | (95%CI) | p | N | β | (95%CI) | p | N | β | (95%CI) | p | N | β | (95%CI) | p | N | β | (95%CI) | p | |

| Prenatal Exposure | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Methyl Bromide | 257 | −0.9 | (−2.5,0.7) | 0.26 | 285 | −0.8 | (−2.4,0.7) | 0.27 | 258 | −0.3 | (−2.0,1.3) | 0.68 | 285 | −1.0 | (−2.8,0.9) | 0.31 | 258 | −0.7 | (−2.3,0.9) | 0.41 |

| Chloropicrin | 257 | −0.7 | (−2.1,0.6) | 0.29 | 285 | −0.6 | (−1.9,0.7) | 0.37 | 258 | −0.3 | (−1.7, 1.1) | 0.68 | 285 | −0.9 | (−2.5,0.7) | 0.28 | 258 | −0.4 | (−1.8, 1.0) | 0.57 |

| Metam Sodium | 257 | 1. 0 | (−0.4, 2.3) | 0.18 | 285 | 0.4 | (−0.8,1.6) | 0.53 | 258 | 0.7 | (−0.7,2.0) | 0.36 | 285 | 0.6 | (−0.9,2.1) | 0.40 | 258 | 0.8 | (−0.6,2.2) | 0.25 |

| 1,3-DCP | 257 | 0.4 | (−1.0,1.8) | 0.56 | 285 | 0.3 | (−0.9,1.6) | 0.61 | 258 | 0.7 | (−0.7,2.2) | 0.30 | 285 | 0.8 | (−0.7,2.4) | 0.31 | 258 | 0.1 | (−1.3,1.5) | 0.90 |

| Postnatal Exposure | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Methyl Bromide | 228 | −2.6 | (−5.2,0.0) | 0.05 | 255 | −1.1 | (−3.5,1.4) | 0.40 | 229 | −1.5 | (−4.1,1.1) | 0.25 | 255 | −2.7 | (−5.6,0.3) | 0.08 | 229 | −2.0 | (−4.6,0.6) | 0.14 |

| Chloropicrin | 228 | −2.4 | (−4.7,−0.2) | 0.04 | 255 | −0.9 | (−3.0,1.2) | 0.41 | 229 | −1.8 | (−4.1,0.4) | 0.11 | 255 | −2.4 | (−5.0,0.2) | 0.07 | 229 | −1.8 | (−4.0,0.4) | 0.12 |

| Metam Sodium | 228 | −0.4 | (−2.7,1.9) | 0.74 | 255 | −0.8 | (−2.9,1.4) | 0.50 | 229 | 0.0 | (−2.2,2.3) | 0.97 | 255 | −0.4 | (−3.0,2.2) | 0.77 | 229 | 0.1 | (−2.2,2.3) | 0.95 |

| 1,3-DCP | 228 | −2.8 | (−6.5,1.0) | 0.15 | 255 | −2.5 | (−6.1,1.2) | 0.18 | 229 | −1.7 | (−5.4,2.1) | 0.38 | 255 | −3.9 | (−8.3,0.5) | 0.09 | 229 | −0.4 | (−4.2,3.3) | 0.82 |

Adjusted for age at assessment, language of assessment, sex, maternal intelligence, maternal education, maternal depression at 7-years, maternal country of birth, HOME score, household poverty level at 7-years, prenatal DAPs and prenatal proximity to agricultural OP use.

With postnatal exposure, IQ scores were generally lower across all domains with increasing wind-adjusted use of methyl bromide, chloropicrin, and 1,3-DCP within 8 km (Table 4), with a marginally significant decrease of 2.6 points (95% CI: −5.2, 0.0) in Full-scale IQ for each ten-fold increase in postnatal methyl bromide use and a decrease of 2.4 points (95% CI: −4.7, −0.2) for each ten-fold increase in postnatal chloropicrin use. Results were similar for postnatal use of methyl bromide and chloropicrin within 5 km and generally null for postnatal use of all fumigants within 3 km and use of metam sodium or 1,3-DCP at any distance (Supplemental Table 2).

Since postnatal use of methyl bromide and chloropicrin within 8 km of residences were both associated with Full-scale IQ, we assessed the effect of postnatal chloropicrin use controlling for methyl bromide use to determine which fumigant is driving the association with Full-scale IQ since methyl bromide and chloropicrin are often used together and are highly correlated; importantly, methyl bromide is currently being replaced by chloropicrin throughout California (CDPR, 2016). In the model evaluating residuals of postnatal methyl bromide when controlling for postnatal chloropicrin use, the effect of a ten-fold increase in postnatal chloropicrin use within 8 km of residences changed directions and was no longer significant (β=1.2; 95% CI: −7.7, 10.1). In the model evaluating residuals of postnatal chloropicrin when controlling for postnatal methyl bromide use, however, the effect of a ten-fold increase in postnatal chloropicrin use within 8 km of residences was similar in direction and magnitude to the original single fumigant model for chloropicrin, but with much wider confidence intervals (β=−3.4; 95% CI: −11.1, 4.3) suggesting that proximity to use of chloropicrin was more influential. The relationship between postnatal chloropicrin use and Full-scale IQ was also similar (β=−3.0; 95% CI: −6.7, 0.7) when controlling for highly correlated prenatal use of chloropicrin (β=−1.1; 95% CI: −2.6, 0.4), suggesting that postnatal use may capture the more critical time period.

There was no relationship between wind-adjusted prenatal or postnatal fumigant use within 8 km of residences and BASC-2 maternal or teacher report of hyperactivity or attention problems (Table 5). There were no associations between prenatal (Supplemental Table 3) or postnatal (Supplemental Table 4) fumigant use within 3 or 5 km of the residence and hyperactivity or attention problems.

Table 5.

Adjusted association between a ten-fold increase in wind-adjusted fumigant use (kg) within 8-km of residences and BASC Attention Problems and Hyperactivity Standardized Scores at 7-years.

| Maternal Reporta | Teacher Reportb | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Attention Problems | Hyperactivity | Attention Problems | Hyperactivity | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| N | β | (95%CI) | p | β | (95%CI) | p | N | β | (95%CI) | p | β | (95%CI) | p | |

| Prenatal Exposure | ||||||||||||||

| Methyl Bromide | 284 | 0.1 | (−1.1,1.4) | 0.83 | 0.0 | (−0.9,1.0) | 0.95 | 234 | 0.0 | (−1.0,1.1) | 0.94 | 0.1 | (−1.2,1.5) | 0.8 7 |

| Chloropicrin | 284 | −0.2 | (−1.3,0.9) | 0.71 | 0.1 | (−0.7,0.9) | 0.77 | 234 | 0.0 | (−0.9,0.9) | 0.96 | 0.2 | (−1.0, 1.3) | 0.78 |

| Metam Sodium | 284 | 0.0 | (−1.0,0.9) | 0.93 | 0.5 | (−0.3,1.2) | 0.23 | 234 | 0.5 | (−0.3,1.2) | 0.23 | −0.3 | (−1.4,0.7) | 0.53 |

| 1,3-DCP | 284 | −0.1 | (−1.1,0.9) | 0.86 | 0.4 | (−0.5,1.2) | 0.39 | 234 | −0.1 | (−1.0,0.7) | 0.73 | −0.5 | (−1.6,0.6) | 0.39 |

| Postnatal Exposure | ||||||||||||||

| Methyl Bromide | 255 | −0.5 | (−2.5,1.4) | 0.60 | −0.5 | (−2.1,1.0) | 0.49 | 211 | −0.6 | (−2.3,1.1) | 0.51 | −0.5 | (−2.6,1.6) | 0.66 |

| Chloropicrin | 255 | −0.4 | (−2.1,1.3) | 0.64 | 0.2 | (−1.0,1.5) | 0.72 | 211 | −0.1 | (−1.6,1.3) | 0.85 | 0.0 | (−1.8,1.8) | 1.00 |

| Metam Sodium | 255 | 0.5 | (−1.2,2.3) | 0.55 | −0.1 | (−1.4,1.2) | 0.88 | 211 | −0.2 | (−1.7,1.2) | 0.75 | 0.4 | (−1.4,2.3) | 0.64 |

| 1,3-DCP | 255 | 0.7 | (−2.1,3.6) | 0.61 | −1.1 | (−3.2,1.1) | 0.34 | 211 | −0.7 | (−3.1,1.8) | 0.59 | −0.2 | (−3.2,2.8) | 0.8 9 |

Adjusted for sex, age at assessment, maternal country of birth, maternal depression and HOME score at 7-years, prenatal DAPs and OP use.

Adjusted for sex, age at assessment, maternal country of birth, HOME score at 7-years, prenatal DAPs and OP use.

Results were similar for fumigant use within 8 km and WISC-IV cognition scales with and without the inclusion of DDT, DDE and PBDEs (not shown) even though the sample sizes were smaller for the models that included these covariates (e.g., n=176 for Full-scale IQ). Excluding the relatively few outliers for postnatal metam sodium use (n=2) and 1,3-DCP use (n=3) did not change our results and there were no outliers with studentized residuals > 3 for models with methyl bromide or chloropicrin use. Associations between postnatal fumigant use and Full-scale IQ were slightly weaker, but similar for both methyl bromide (β=−2.3; 95% CI: −4.7, 0.1) and chloropicrin (β=−2.2; 95% CI: −4.2, −0.3) when we used inverse probability weighting to adjust for potential selection bias. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, which is not common practice in environmental epidemiological studies, none of our associations reached significance at the critical p-value = 0.003.

4. Discussion

We observed a suggestive association between Full-Scale IQ and postnatal proximity to agricultural use of methyl bromide and chloropicrin during childhood. Adjusted for covariates and other exposures, a ten-fold increase in methyl bromide or chloropicrin use within 8 km of the residence during the child’s lifetime was associated with an approximately 2.5 point decrease in Full-Scale IQ. In our population, fumigant use increased 100-fold from the 5th to the 95th percentiles of the distribution for both methyl bromide and chloropicrin suggesting a potentially five point decrease in Full-Scale IQ, or one third of a standard deviation, for children with the highest use of these fumigants near their residences during their lifetime. Including both methyl bromide and chloropicrin in the same model using residuals suggests that use of chloropicrin is more influential, but the use of these fumigants was highly correlated and difficult to disentangle in this cohort. We observed a marginal association between proximity to higher prenatal use of methyl bromide and chloropicrin within 3 km and poorer Processing Speed; there were no other relationships between prenatal fumigant use and cognition. There were no associations between prenatal or postnatal fumigant use and attention or hyperactivity. These results need to be replicated in a larger study with sufficient power to evaluate multiple comparisons of fumigant use and neurodevelopment.

Previous studies observed poorer neurologic test scores,(Acuna et al., 1997) more concentration and attention problems (Magnavita, 2009) and memory impairment (Acuna et al., 1997; Magnavita, 2009) in workers exposed to methyl bromide. A case study found problems with concentration, memory and processing as well as increased anxiety after exposure to methyl bromide from home fumigation (Reidy et al., 1994). Among pesticide applicators, those that applied fumigants had higher odds of reporting more neurologic symptoms including difficulty concentrating and absentmindedness [odds ratio (OR) = 1.5; 95% CI: 1.2 – 1.8] than those that did not apply fumigants (Kamel et al., 2005). Residents exposed to metam sodium after a spill reported higher levels of depression and anxiety than those that were not exposed (Bowler et al., 1994a). This is the first study to evaluate prenatal and postnatal residential proximity to agricultural fumigant use and cognitive development in children.

One challenge in utilizing PUR data to characterize exposure is selecting appropriate distances from the residence to summarize pesticide use. In this cohort, we previously reported associations between Full-scale IQ at 7-years of age and prenatal OP insecticide use within 1 km of maternal residences during pregnancy (Gunier et al., 2016; Rowe et al., 2016) and also with other potentially neurotoxic pesticides including carbamates, neonicotinoids, pyrethroids and maneb (Gunier et al., 2016). A study utilizing California PUR data observed higher odds of autism spectrum disorder (OR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.0 – 2.5) with any use of OP insecticides within 1.5 km of their residence during the prenatal period (Shelton et al., 2014). Previous studies that have evaluated prenatal residential proximity to fumigant use using PUR data found no association with autism (Roberts et al., 2007) or neural tube defects (Rull et al., 2006) using a buffer distance of 1 km from the residence. However, for methyl bromide, reported use from PUR data within a 7 × 7 square mile area (∼ 8 km) of the residence explained the largest amount of the variation (95%) in measured concentrations of methyl bromide in community air (Li et al., 2005). Other studies have also demonstrated fumigant drift far (5 – 20 km) from application sites (Cryer and van Wesenbeeck, 2011; van Wesenbeeck et al., 2016), suggesting that using smaller buffer distances (< 3 km) to summarize fumigant use underestimates exposure by excluding applications farther from the residence that influence air concentrations, resulting in exposure misclassification.

There are several limitations of this study. Residential proximity to agricultural fumigant use is not a direct measure of personal exposure. More research is needed to evaluate the relationship between reported fumigant use and measured concentrations in ambient and personal air samples. Additionally, we were unable to include potential exposure from fumigant use near schools, workplaces, or other locations where mothers and children spend significant amounts of time. Our samples size for this analysis was relatively small when restricted to participants with mostly complete residential history. We also made numerous statistical comparisons with four fumigants, two time periods, three distances and three health outcomes; therefore the associations we observed should be interpreted with caution.

Our study also had several strengths. Reporting agricultural fumigant applications is mandatory and closely regulated in California because these fumigants are restricted use pesticides, minimizing potential reporting bias. We incorporated wind direction for the seven days after fumigant applications to account for dispersion from the application site for these highly volatile compounds. Since validated biomarkers of environmental exposure are not available for these fumigants, residential proximity to agricultural applications from PUR data is one of the only methods for characterizing exposure. The CHAMACOS cohort is a relatively homogeneous population with extensive data on covariates and other environmental exposures that are related to cognition and behavior in children, allowing for better control of confounding. Our results were similar using inverse probability weighting; therefore we do not believe that there was a large impact from selection bias.

Future research is needed to develop better prediction models for human exposure using PUR data and existing measurements of fumigant concentrations in outdoor air. These fumigant exposure models could be used in larger epidemiological studies that combine cohorts or use available data to assess the relationship between agricultural fumigant use and neurodevelopment in children. There is also a need for further development of statistical methods for analyzing environmental exposures to highly correlated chemical mixtures (Rider et al., 2013).

5. Conclusions

We observed decreases in Full-scale intelligence quotient with increasing methyl bromide and chloropicrin use within 8 km of residences during the child’s lifetime. However, these results should be interpreted with caution until further explored in larger studies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Full-scale IQ decreased with greater lifetime proximity to methyl bromide use.

Full-scale IQ decreased with greater lifetime proximity to chloropicrin use.

There was no association between prenatal fumigant use and cognition.

There was no association between fumigant use and hyperactivity or attention.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant number R56ES023591and P01 ES009605 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and R82670901 and RD83451301 from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Abbreviations

- 1,3-DCP

1,3-dichloropropene

- BASC-2

Behavioral Assessment System for Children 2

- CHAMACOS

Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas

- CI

confidence interval

- DAP

dialkyl phosphate

- DDT

p, p’-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethylene

- DDE

p, p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene

- HOME

Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment

- IQ

intelligence quotient

- OP

organophosphate

- OR

odds ratio

- PBDE

polybrominated diphenyl ether

- PPVT

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test

- TVIP

Test de Vocabulario en Imagenes Peabody

- WISC-IV

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th edition

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement of financial interest:

Dr. Asa Bradman is a volunteer member of the Board for The Organic Center, a non-profit organization addressing scientific issues around organic food and agriculture. None of the other authors declares any actual or potential competing financial interest.

References

- Acuna MC, Diaz V, Tapia R, Cumsille MA. [Assessment of neurotoxic effects of methyl bromide in exposed workers] Rev Med Chil. 1997;125:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Dichloropropenes. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2008 Available: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp40.pdf. [PubMed]

- Ben Slamia L, Harzallah S, Lamouchi T, Sakli G, Dogui M, Ben Amou S. Peripheral neuropathy induced by acute methyl bromide skin exposure: a case report. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2006;162:1257–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(06)75140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop CM. A case of methyl bromide poisoning. Occup Med (Lond) 1992;42:107–109. doi: 10.1093/occmed/42.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard MF, Chevrier J, Harley KG, Kogut K, Vedar M, Calderon N, Trujillo C, Johnson C, Bradman A, Barr DB, Eskenazi B. Prenatal exposure to organophosphate pesticides and IQ in 7-year-old children. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:1189–1195. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler RM, Mergler D, Huel G, Cone JE. Aftermath of a chemical spill: psychological and physiological sequelae. Neurotoxicology. 1994a;15:723–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler RM, Mergler D, Huel G, Cone JE. Psychological, psychosocial, and psychophysiological sequelae in a community affected by a railroad chemical disaster. J Trauma Stress. 1994b;7:601–624. doi: 10.1007/BF02103010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradman A, Eskenazi B, Barr DB, Bravo R, Castorina R, Chevrier J, Kogut K, Harnly ME, McKone TE. Organophosphate urinary metabolite levels during pregnancy and after delivery in women living in an agricultural community. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1802–1807. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradman AS, Schwartz JM, Fenster L, Barr DB, Holland NT, Eskenazi B. Factors predicting organochlorine pesticide levels in pregnant Latina women living in a United States agricultural area. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2007;17:388–399. doi: 10.1038/sj.jes.7500525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell B, Bradley R. Home observation for measurement of the environment. University of Arkansas; Little Rock, AR: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Pesticide Regulation. Correlating Agricultural Use With Ambient Concentration of The Fumigant Chloropicrin During The Period Of 2011–2014. Sacramento, CA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Pesticide Regulation. Analysis of Agricultural Use and Average Concentrations of 1,3-Dichloropropene in Nine Communities of California in 2006 – 2015, and Calculation of a Use Limit (Township Cap) Sacramento, CA: 2016a. [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Pesticide Regulation. Correlating Agricultural Use With Ambient Air Concentrations Of Methyl Isothiocyanate During The Period of 2011 – 2014. Sacramento, CA: 2016b. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael SL, Yang W, Roberts E, Kegley SE, Padula AM, English PB, Lammer EJ, Shaw GM. Residential agricultural pesticide exposures and risk of selected congenital heart defects among offspring in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Environ Res. 2014;135:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castorina R, Bradman A, Sjodin A, Fenster L, Jones RS, Harley KG, Eisen EA, Eskenazi B. Determinants of serum polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) levels among pregnant women in the CHAMACOS cohort. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:6553–6560. doi: 10.1021/es104295m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalleri F, Galassi G, Ferrari S, Merelli E, Volpi G, Gobba F, Del Carlo G, De Iaco A, Botticelli AR, Rizzuto N. Methyl bromide induced neuropathy: a clinical, neurophysiological, and morphological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:383. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDPR, California Department of Pesticide Regulation. Air Monitoring Network Results. Sacramento, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- CDPR, California Department of Pesticide Regulation. Pesticide Use Reporting (PUR) Sacramento, CA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CDWR, California Department of Water Resources. California Irrigation Management Information System. Sacramento, CA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Census, U.S.B.o.t. Poverty Thresholds, Current Population Survey. U.S. Bureau of the Census; Washington, D.C: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cryer SA, van Wesenbeeck IJ. Coupling field observations, soil modeling, and air dispersion algorithms to estimate 1,3-dichloropropene and chloropicrin flux and exposure. J Environ Qual. 2011;40:1450–1461. doi: 10.2134/jeq2010.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila M, McFall SL, Cheng D. Acculturation and depressive symptoms among pregnant and postpartum Latinas. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:318–325. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L, Dunn L. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Revised. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Chevrier J, Rauch SA, Kogut K, Harley KG, Johnson C, Trujillo C, Sjodin A, Bradman A. In utero and childhood polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) exposures and neurodevelopment in the CHAMACOS study. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:257–262. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Ajwa H, Qin R, Stanghellini M, Sullivan D. Emission and transport of 1,3-dichloropropene and chloropicrin in a large field tarped with VaporSafe TIF. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:405–411. doi: 10.1021/es303557y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar FW, Harley KG, Kogut K, Chevrier J, Mora AM, Sjodin A, Eskenazi B. Prenatal DDT and DDE exposure and child IQ in the CHAMACOS cohort. Environ Int. 2015;85:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmill A, Gunier RB, Bradman A, Eskenazi B, Harley KG. Residential proximity to methyl bromide use and birth outcomes in an agricultural population in California. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:737–743. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube A, Donaldson D, Kiely T, Wu L. In: Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage 2006 & 2007 Market Estimates. Agency USEP, editor. Washington D.C: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gunier RB, Bradman A, Harley KG, Kogut K, Eskenazi B. Prenatal Residential Proximity to Agricultural Pesticide Use and IQ in 7-Year-Old Children. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 doi: 10.1289/EHP504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunier RB, Harnly ME, Reynolds P, Hertz A, Von Behren J. Agricultural pesticide use in California: pesticide prioritization, use densities, and population distributions for a childhood cancer study. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:1071–1078. doi: 10.1289/ehp.011091071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunier RB, Ward MH, Airola M, Bell EM, Colt J, Nishioka M, Buffler PA, Reynolds P, Rull RP, Hertz A, Metayer C, Nuckols JR. Determinants of agricultural pesticide concentrations in carpet dust. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:970–976. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med. 1990;9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan JW, Lancaster T. Instrumental variables and inverse probability weighting for causal inference from longitudinal observational studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 2004;13:17–48. doi: 10.1191/0962280204sm351ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustinx WN, van de, Laar RT, van Huffelen AC, Verwey JC, Meulenbelt J, Savelkoul TJ. Systemic effects of inhalational methyl bromide poisoning: a study of nine cases occupationally exposed due to inadvertent spread during fumigation. Br J Ind Med. 1993;50:155–159. doi: 10.1136/oem.50.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel F, Engel LS, Gladen BC, Hoppin JA, Alavanja MC, Sandler DP. Neurologic symptoms in licensed private pesticide applicators in the agricultural health study. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:877–882. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, McLaughlin R, Harnly M, Gunier R, Kreutzer R. Community exposures to airborne agricultural pesticides in California: ranking of inhalation risks. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:1175–1184. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Mehler L, Beckman J, Diebolt-Brown B, Prado J, Lackovic M, Waltz J, Mulay P, Schwartz A, Mitchell Y, Moraga-McHaley S, Gergely R, Calvert GM. Acute pesticide illnesses associated with off-target pesticide drift from agricultural applications: 11 States, 1998–2006. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:1162–1169. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Johnson B, Segawa R. Empirical relationship between use, area, and ambient air concentration of methyl bromide. J Environ Qual. 2005;34:420–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita N. A cluster of neurological signs and symptoms in soil fumigators. J Occup Health. 2009;51:159–163. doi: 10.1539/joh.n8007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks AR, Harley K, Bradman A, Kogut K, Barr DB, Johnson C, Calderon N, Eskenazi B. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and attention in young Mexican-American children: the CHAMACOS study. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1768–1774. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky E, Schwartz J, Coull BA, Koutrakis P, Wellenius GA, Suh HH, Gold DR, Mittleman MA. Modeling the association between particle constituents of air pollution and health outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:317–326. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy TJ, Bolter JF, Cone JE. Neuropsychological sequelae of methyl bromide: a case study. Brain Inj. 1994;8:83–93. doi: 10.3109/02699059409150961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. BASC-2: Behaviour Assessment System for Children, Second Edition Manual. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rider CV, Carlin DJ, Devito MJ, Thompson CL, Walker NJ. Mixtures research at NIEHS: an evolving program. Toxicology. 2013;313:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts EM, English PB, Grether JK, Windham GC, Somberg L, Wolff C. Maternal residence near agricultural pesticide applications and autism spectrum disorders among children in the California Central Valley. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1482–1489. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe C, Gunier R, Bradman A, Harley KG, Kogut K, Parra K, Eskenazi B. Residential proximity to organophosphate and carbamate pesticide use during pregnancy, poverty during childhood, and cognitive functioning in 10-year-old children. Environ Res. 2016;150:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rull RP, Ritz B, Shaw GM. Neural tube defects and maternal residential proximity to agricultural pesticide applications. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:743–753. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JF, Geraghty EM, Tancredi DJ, Delwiche LD, Schmidt RJ, Ritz B, Hansen RL, Hertz-Picciotto I. Neurodevelopmental disorders and prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticides: the CHARGE study. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:1103–1109. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TeSlaa G, Kaiser M, Biederman L, Stowe CM. Chloropicrin toxicity involving animal and human exposure. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1986;28:323–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Bureau of the Census. Poverty Thresholds 2008. Current Population Survey 2008 [Google Scholar]

- van Wesenbeeck IJ, Cryer SA, de Cirugeda Helle O, Li C, Driver JH. Comparison of regional air dispersion simulation and ambient air monitoring data for the soil fumigant 1,3-dichloropropene. Sci Total Environ. 2016;569–570:603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verberk MM, Rooyakkers-Beemster T, de Vlieger M, van Vliet AG. Bromine in blood, EEG and transaminases in methyl bromide workers. Br J Ind Med. 1979;36:59–62. doi: 10.1136/oem.36.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) Administration and Scoring Manual. Harcourt Assessment Incorporated; San Antonio, TX: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock R, Munoz-Sandoval A. Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery - Revised. Riverside Publishing; Itasca, IL: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Carmichael SL, Roberts EM, Kegley SE, Padula AM, English PB, Shaw GM. Residential agricultural pesticide exposures and risk of neural tube defects and orofacial clefts among offspring in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:740–748. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.